Abstract

Benefit of blood pressure (BP)-lowering treatment on various outcomes was evaluated by meta-analyses restricted to randomized controlled trials (RCTs) measuring all major outcomes. The question whether BP-lowering and each class of antihypertensive agents prevent “new-onset” heart failure was explored by additional meta-analyses limited to RCTs excluding baseline heart failure from randomization. Thirty-five BP-lowering RCTs measured all outcomes, and heart failure [RR 0.63 (0.52–0.75)] and stroke [RR 0.58 (0.49–0.68)] were the outcomes most effectively prevented. Heart failure and stroke reductions were significantly related to systolic BP, diastolic BP, and pulse pressure reductions. In 18 BP-lowering RCTs excluding baseline heart failure from recruitment, heart failure reduction (“new-onset” heart failure) [RR 0.58 (0.44–0.75)] was very similar to that observed in the entire set of RCTs. In meta-analyses of head-to-head comparisons of different antihypertensive classes, calcium antagonists were inferior in preventing “new-onset” heart failure [RR 1.16 (1.01–1.33)]. However, this inferiority disappeared when meta-analysis was limited to RCTs allowing concomitant use of diuretics, beta-blockers, or renin-angiotensin system blockers, also in the calcium antagonist group [RR 0.96 (0.81–1.12)]. BP-lowering treatment effectively prevents “new-onset” heart failure. It is suggested that BP lowering by calcium antagonists is effective as BP lowering by other drugs in preventing “new-onset” heart failure, unless the trial design creates an unbalance against calcium antagonists.

† Deceased

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Blood pressure-lowering trials

- Cardiovascular death

- Coronary heart disease

- Heart failure

- Hypertension

- Meta-analysis

- Randomized controlled trials

- Stroke

1 Antihypertensive Treatment and Heart Failure: Prevention of Recurrences or Prevention of New-Onset Heart Failure?

Moser and Hebert were the first to call attention to the finding that blood pressure (BP)-lowering treatment did not only reduce risk of fatal and nonfatal stroke and fatal and nonfatal coronary heart disease (CHD) events but also risk of heart failure [1]. They reviewed data from 12 placebo (or no treatment)-controlled randomized trials (RCTs) including 13,837 hypertensive patients and calculated heart failure risk was reduced by 51% (risk ratio [RR] and 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.48 [0.38–0.59]). They also remarked that most of the positive RCTs they had considered had used a diuretic as BP-lowering drug [1].

In a very large meta-analysis updated to end 2013 and including 68 RCTs on as many as 245,885 participants, we extended Moser and Herbert’s early analysis and we demonstrated that heart failure risk was significantly reduced by a standardized systolic BP/diastolic BP reduction of 10/5 mmHg and that heart failure reduction was even numerically greater than that of stroke (−43% vs. −38%) and much greater than the albeit significant reductions of CHD events and cardiovascular and all-cause mortality [2]. A more stringent comparison was subsequently done by our group by restricting meta-analyses to only those 35 BP-lowering RCTs (146,810 individuals) measuring all major cause-specific events (stroke, CHD, heart failure, cardiovascular mortality) [3], and we reported that heart failure and stroke were by far the outcomes most extensively reduced by BP lowering (RR stroke 0.58 [0.49–0.68]; heart failure 0.63 [0.52–0.75]), without a significant difference between the two reductions. We also calculated a meta-regression to compare the relationships between the relative risk reductions of the various outcomes with the extent of BP reduction [3] and found the steepest slopes for the relationships with heart failure and stroke with no significant differences between these slopes (p = 0.69, 0.78, and 0.67 for systolic BP, diastolic BP, and pulse pressure reductions, respectively). On the other hand, the slopes of heart failure reduction were significantly greater than those of all-cause mortality reduction (p = 0.022, 0.024 for systolic BP and pulse pressure reductions), although decreased mortality (both cardiovascular and all-cause) was also a significant effect. In no one of our meta-regression analyses was coronary heart disease reduction significantly related to the extent of blood pressure reduction (Fig. 18.1).

Relationships of outcome reductions to the extent of BP reductions, in the 35 blood pressure-lowering trials in which all the listed outcomes were measured. Meta-regressions of risk ratios (RR) on absolute systolic blood pressure (SBP) differences (D) (active treatment minus placebo or less active treatment). Stroke is the green continuous line, coronary heart disease (CHD) the blue square line, heart failure (HF) the red short dashed line, cardiovascular (CV) death the orange long dashed line, and all-cause death the black dashed and dotted line. P-values indicate statistical significance of the slope of each outcome (colors as above to identify outcomes) on BP difference. Note the ordinates are on a ln scale. Modified from Thomopoulos et al. [3], by courtesy of Journal of Hypertension

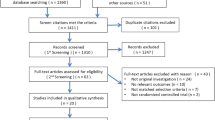

A further important question is whether BP-lowering treatment really prevents “new-onset” heart failure or mostly reduces recurring or worsening of preexisting heart failure. A correct analysis implied meta-analysis of only those BP-lowering RCTs explicitly excluding patients with history or current evidence of heart failure. Of the 35 BP-lowering RCTs measuring heart failure as an outcome, our search identified 18 in which baseline history of HF was explicitly listed as an exclusion criterion [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31] and, therefore, suitable to be meta-analyzed to estimate the BP-lowering preventive effect on “new-onset” heart failure. Our search also identified other ten RCTs in which only patients with mild heart failure could have been included; added to the 18 RCTs with no baseline HF, they were used for a secondary meta-analysis (Table 18.1).

Even with the more stringent criteria of including RCTs with no baseline heart failure (Fig. 18.2), there was a large and highly significant reduction of “new-onset” heart failure, the extent of which (relative risk reduction −42%, absolute reduction −21 heart failure cases per 1000 patients treated 5 years) is very similar to that in the entire set of RCTs measuring heart failure as an outcome (relative risk reduction −37%, absolute risk reduction −19 heart failure cases). Also the secondary meta-analysis using looser criteria in selection of RCTs did not substantially change the quantitative assessment of the effectiveness of BP-lowering treatment in the prevention of development of new HF (Fig. 18.2).

Relative and absolute risk reduction of heart failure in blood pressure lowering in trials with no baseline heart failure (A) and with no or mild baseline heart failure (B). Each column from left to right indicates numbers (n) of trials considered, the number of heart failure (HF) events observed and the number of patients followed up, the difference in systolic and diastolic blood pressure (SBP/DBP) achieved between actively treated patients (treated) and controls, the risk ratio (RR) and its 95% confidence interval (CI) standardized by a 10/5 mmHg difference, the standardized risk ratio as forest plot, and the absolute risk reduction as number and 95% CI of events prevented every 1000 patients treated for 5 years. Modified from Thomopoulos et al. [3], by courtesy of Journal of Hypertension

2 Are the Various Classes of Antihypertensive Drugs Equally Effective in Preventing “New-Onset” Heart Failure?

Other clinically relevant questions are: Are all classes of BP-lowering drugs capable of significantly reducing “new-onset” heart failure, and, when directly (head-to-head) compared, are classes equally effective? A correct answer to these questions again required analyses limited to RCTs excluding baseline heart failure.

The first part of this question (i.e., the ability of each drug class to reduce new-onset heart failure) was approached by meta-analyzing placebo-controlled BP-lowering trials stratified by the class of the active drug compared with placebo. Among the BP-lowering RCTs that had rigorously excluded patients with baseline heart failure, four had BP lowering induced or initiated by a diuretic, two by a beta-blocker, four by a calcium antagonist, five by an ACE inhibitor, and two by an angiotensin receptor blocker (Table 18.1, column “Drug class”). In meta-analyses restricted to RCTs with no baseline heart failure (Fig. 18.3a), BP lowering by diuretics, beta-blockers, calcium antagonists, and ACE inhibitors significantly reduced the risk of new heart failure. Inability to find a significant heart failure reduction with angiotensin receptor blockers is likely to depend on insufficient statistical power (only two RCTs) associated with a small systolic BP/diastolic BP difference.

Effects of blood pressure lowering by each of five major classes of drugs compared with placebo (A) and with different classes of drugs (head-to-head comparisons) (B) on new-onset heart failure (trials with no baseline heart failure). Columns from left to right are numbers (n) of comparisons, the difference in systolic and diastolic blood pressure (SBP/DBP) achieved between treatment groups (negative numbers indicate lower BP with the first drug and positive numbers lower BP with the control), the number of heart failure (HF) events observed and the number of patients followed up, the risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) calculated with the observed SBP/DBP difference, and the risk ratio represented as forest plot. ACEI angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARB angiotensin receptor blockers, BB beta-blockers, CA calcium antagonists, D diuretics, PL placebo, RASB renin-angiotensin system blockers, vs. versus. The asterisks indicate RR calculated with the fixed effect model and the crosses RR values adjusted for the SBP/DBP difference. Modified from Thomopoulos et al. [3], by courtesy of Journal of Hypertension

The second part of the question (i.e., the relative effectiveness of the various drug classes) was explored by using a second set of meta-analyses, focused on direct head-to-head comparisons of different active BP-lowering drugs, the only correct way of evaluating the relative effectiveness of two interventions. To investigate the more general question of the comparative effectiveness of various drug classes on cardiovascular outcomes, we had previously identified 50 RCTs with 58 two-drug comparisons, but of these trials, only 34 with 40 comparisons measured heart failure in addition to other outcomes. Among these head-to-head comparison trials, 18 RCTs had excluded baseline heart failure from recruitment, and seven had only allowed mild heart failure [6, 28, 33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55]. These trials allowed studying the relative effectiveness of the various drug classes in the prevention of “new-onset” heart failure (Table 18.2). Figure 18.3b shows that, even when only RCTs explicitly excluding baseline heart failure were considered, calcium antagonists were found to be significantly inferior to all other drugs in preventing “new-onset” heart failure. No significant differences were found in all other comparisons, except for some superiority of diuretics vs. all other drugs together. Separate secondary meta-analyses including also RCTs allowing inclusion of mild heart failure gave results overlapping with those of the primary analyses shown in Fig. 18.3b.

3 Does the Apparent Inferiority of Calcium Antagonists in Preventing New Onset of Heart Failure Depend on Their Pharmacological Properties or on the Design of the Trials?

An additional important question is whether the reported statistically significant inferiority of calcium antagonists in HF risk prevention [8] really depends on pharmacological properties of this drug class or rather results from the design of many trials forbidding the concomitant use of drugs known to be active in HF treatment in the calcium antagonist group but not in the other one.

Of the 13 comparisons of calcium antagonists with other classes of BP-lowering drugs in 12 RCTs excluding preexisting heart failure at baseline, four were in RCTs whose design allowed the concomitant use of diuretics, beta-blockers, or renin-angiotensin system blockers in the calcium antagonist group:

-

In ACCOMPLISH [33], patients were randomized either to the association of benazepril-amlodipine or benazepril-hydrochlorothiazide; therefore both treatment groups equally received the ACE inhibitor benazepril.

-

In the ASCOT-BPA trial [43], patients randomized to the calcium antagonist amlodipine could receive as second drug the ACE inhibitor perindopril (mean 58.5% throughout the time), and in the control group, patients initially randomized to the beta-blocker atenolol could receive as second drug a thiazide diuretic (mean 65.7% throughout the trial).

-

In CAMELOT [6], background therapy with a diuretic was given to 32% of patients randomized to amlodipine and to 27% of those randomized to enalapril, and a beta-blocker was given to 74% and 75% of the patients randomized, respectively, to the calcium antagonist and the ACE inhibitor.

-

In CASE-J [45], patients randomized to amlodipine and those to the angiotensin receptor blocker candesartan could additionally receive a diuretic (14% in the amlodipine group and 25% in the candesartan group) and a beta-blocker (17% and 22%, respectively).

On the other hand, in eight RCTs (nine comparisons), the trial design prevented the use of all or part of drugs active in the treatment of heart failure:

-

In ALLHAT [34], patients receiving a calcium antagonist could not receive diuretics and renin-angiotensin system blockers (but only beta-blockers, reserpine, or clonidine) as second drugs.

-

In INSIGHT [37], all patients in the control group received a diuretic, which could not be administered in the calcium antagonist group, whereas only a minority of patients in both the groups concomitantly received either a beta-blocker or an ACE inhibitor.

-

In JMIC-B [47], control patients received an ACE inhibitor, which could not be prescribed in the calcium antagonist group, with less than 25% of patients in either group concomitantly receiving a beta-blocker.

-

In MIDAS [38], administration of a diuretic was reserved to the control group and prohibited to the calcium antagonist group, with 25–28% of patients in either group concomitantly receiving the ACE inhibitor enalapril.

-

In NICS-EH [39], a thiazide diuretic was given to all patients in the control group and prohibited in the patients randomized to the calcium antagonist nicardipine.

-

In CONVINCE [46], diuretics were used in only 26% of the verapamil patients and in 44% of control patients, and beta-blockers could not be prescribed to verapamil patients, but they were prescribed to 43% of patients in the control group.

-

In NORDIL [48], diuretics were used in 17% of the diltiazem patients and in 43% of the control patients and beta-blockers in 13% and 66% of the diltiazem and control patients, respectively.

-

In VHAS [40], diuretics were used only in the control arm and were forbidden in the verapamil arm, with only one patient out of the four receiving an ACE inhibitor in both arms.

Separate meta-analyses of the two sets of RCTs are summarized in Fig. 18.4. In those RCTs in which some of the drug classes effective in heart failure treatment could be administered in both the calcium antagonist and the control group, no significant difference occurred in the risk of “new-onset” heart failure between the two treatment groups (RR 0.96 [0.81–1.12]) (Fig. 18.4b), whereas a higher heart failure risk occurred in those RCTs, the design of which prevented addition of drugs effective in heart failure treatment to the patients randomized to calcium antagonists (RR 1.27 [1.14–1.42]) (Fig. 18.4a). The difference between the RRs of the two groups is statistically significant (p = 0.002).

Separate meta-analyses of trials comparing calcium antagonists with other blood pressure-lowering drugs according to trial design: (A) forbidding concomitant use of diuretics, beta-blockers, and renin-angiotensin system blockers in the calcium antagonist treatment group and (B) allowing concomitant use of diuretics, beta-blockers, and renin-angiotensin system blockers also in the calcium antagonist treatment group. Trials with no baseline heart failure. Each row reports data from single trials (indicated by acronym and drug comparison). Columns from left to right: between group systolic/diastolic blood pressure (SBP/DBP) differences, number (n) of heart failure (HF) events and number of patients in each treatment group, risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI), RR forest plots, and P-value for heterogeneity for the two meta-analyses. ACEI angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, ARB angiotensin receptor blockers, BB beta-blockers, CA calcium antagonists, D diuretics, PL placebo, vs. versus. P-value for differences between RR in meta-analysis A and RR in meta-analysis B is 0.002. The symbol † indicates RR value adjusted for the SBP/DBP difference. From Thomopoulos et al. [3], by courtesy of Journal of Hypertension

4 Conclusions

-

1.

Heart failure is with stroke one of the two cardiovascular outcomes that are reduced by BP-lowering treatment to the greatest extent, without a clear preference for either outcome.

-

2.

Meta-analysis of only those RCTs that specifically excluded baseline heart failure allows the conclusion that heart failure risk reduction mostly consists of prevention of the clinical manifestations of “new-onset” heart failure, at least as clinically diagnosed by hospital physicians.

-

3.

BP lowering by any of the five major classes of BP-lowering drugs (diuretics, beta-blockers, calcium antagonists, ACE inhibitors, and angiotensin receptor blockers) can significantly reduce the risk of “new-onset” heart failure. This means that, when the possibility of recurrence or worsening of preexisting heart failure is avoided, the preventing effect of BP lowering by calcium antagonists on heart failure also achieves statistical significance.

-

4.

When RCTs head-to-head comparing different classes of agents have been used in order to appropriately explore whether all antihypertensive drug classes are equally effective in preventing new heart failure, calcium antagonists have been found significantly less effective than the other drug classes in the prevention of new-onset heart failure.

-

5.

However, we have found that inferiority of calcium antagonists in heart failure prevention occurs only in those RCTs whose design forbade or limited the use of diuretics, beta-blockers, or renin-angiotensin system blockers as accompanying drugs in the calcium antagonist arm but not in the control arm. On the other hand, the calcium antagonist inferiority did not occur in the RCTs allowing the use of the abovementioned drugs also in the calcium antagonist arm. These findings support the hypothesis that the inferiority of calcium antagonists as far as new heart failure is concerned may depend, at least to a large extent, on an unequal use of accompanying drugs in such a way that the larger use of drugs known to reduce heart failure symptoms (diuretics, beta-blockers, and renin-angiotensin system blockers) in the control arms may mask onset of heart failure symptoms to a greater extent in control patients and create an imbalance against calcium antagonists. This interpretation supports the concept that, as for most outcomes, also the preventive effect of BP lowering on new heart failure basically depends on the lowering of BP independently of the drugs by which BP is reduced and suggests the clinical value of the association of calcium antagonists with any of the agents known to alleviate heart failure symptoms.

References

Moser M, Hebert PR. Prevention of disease progression, left ventricular hypertrophy and congestive heart failure in hypertension treatment trials. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;27:1214–8.

Thomopoulos C, Parati G, Zanchetti A. Effects of blood pressure lowering on outcome incidence in hypertension. 1. Overview, meta-analyses and meta-regression analyses of randomized trials. J Hypertens. 2014;32:2285–95.

Thomopoulos C, Parati G, Zanchetti A. Effects of blood pressure lowering treatment. 6. Prevention of heart failure and new-onset heart failure—meta-analyses of randomized trials. J Hypertens. 2016;34:373–84.

Poole-Wilson PA, Lubsen J, Kirwan BA, van Dalen FJ, Wagener G, Danchin N, et al. Effect of long-acting nifedipine on mortality and cardiovascular morbidity in patients with stable angina requiring treatment (ACTION trial): randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364:849–57.

Management Committee. The Australian therapeutic trial in mild hypertension. Lancet. 1980;315:1261–7.

Nissen SE, Tuzcu EM, Libby P, Thompson PD, Ghali M, Garza D, et al. Effect of antihypertensive agents on cardiovascular events in patients with coronary disease and normal blood pressure: the CAMELOT study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;292:2217–25.

Amery A, Brixko P, Clement D, De Schaepdryver A, Fagard R, Forte J, et al. Mortality and morbidity results from the European Working Party on High Blood Pressure in the Elderly Trial. Lancet. 1985;325:1349–54.

Coope J, Warrender TS. Randomised trial of treatment of hypertension in elderly patients in primary care. BMJ. 1986;293:1145–51.

Hypertension-Stroke Cooperative Study Group. Effect of antihypertensive treatment on stroke recurrence. JAMA. 1974;229:409–18.

Beckett NS, Peters R, Fletcher AE, Staessen JA, Liu L, Dumitrascu D, et al. Treatment of hypertension in patients 80 years of age or older. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1887–98.

Helgeland A. Treatment of mild hypertension: a five year controlled drug trial. The Oslo study. Am J Med. 1980;69:725–32.

Liu L, Wang JG, Gong L, Liu G, Staessen JA. Comparison of active treatment and placebo in older Chinese patients with isolated systolic hypertension. Systolic hypertension in China (Syst-China) collaborative group. J Hypertens. 1998;16:1823–9.

Staessen JA, Fagard R, Thijs L, Celis H, Arabidze GG, Birkenhäger WH, et al. Randomised double-blind comparison of placebo and active treatment for older patients with isolated systolic hypertension. The Systolic Hypertension in Europe (Syst-Eur) Trial Investigators. Lancet. 1997;350:757–64.

Smith WM. Treatment of mild hypertension: results of a ten-year intervention trial. Circ Res. 1977;40:I98–105.

JATOS Study Group. Principal results of the Japanese trial to assess optimal systolic blood pressure in elderly hypertensive patients (JATOS). Hypertens Res. 2008;31:2115–27.

UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group. Tight blood pressure control and risk of macrovascular and microvascular complications in type 2 diabetes: UKPDS 38. Br Med J. 1998;317:703–13.

Marre M, Lievre M, Chatellier G, Mann JF, Passa P, Ménard J, DIABHYCAR Study Investigators. Effects of low dose ramipril on cardiovascular and renal outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and raised excretion of urinary albumin: randomised, double blind, placebo controlled trial (the DIABHYCAR study). Br Med J. 2004;328:495.

DREAM Trial Investigators. Effects of ramipril and rosiglitazone on cardiovascular and renal outcomes in people with impaired glucose tolerance or impaired fasting glucose: results of the diabetes REduction assessment with ramipril and rosiglitazone medication (DREAM) trial. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:1007–14.

The Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation Study Investigators. Effects of an angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor, ramipril, on cardiovascular events in high-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:145–53.

Brenner BM, Cooper ME, de Zeeuw D, Keane WF, Mitch WE, Parving HH, et al. Effects of losartan on renal and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:861–9.

Telmisartan Randomized Assessment Study in ACE Intolerant Subjects with Cardiovascular Disease (TRANSCEND) Investigators. Effects of the angiotensin-receptor blocker telmisartan on cardiovascular events in high-risk patients intolerant to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;372:1174–83.

ADVANCE Collaborative Group. Effects of a fixed combination of perindopril and indapamide on macrovascular and microvascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (the ADVANCE trial): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;37:829–40.

Liu L, Zhang Y, Liu G, Li W, Zhang X, Zanchetti A. The Felodipine event reduction (FEVER) study: a randomized long-term placebo controlled trial in Chinese hypertensive patients. J Hypertens. 2005;23:2157–72.

Perry HM Jr, Smith WM, McDonald RH, Black D, Cutler JA, Furberg CD, et al. Morbidity and mortality in the systolic hypertension in the elderly program (SHEP) pilot study. Stroke. 1989;20:4–13.

SHEP Co-operative Research Group. Prevention of stroke by antihypertensive drug treatment in older persons with isolated systolic hypertension. Final results of the systolic hypertension in the elderly program (SHEP). JAMA. 1991;265:3255–64.

Dahlöf B, Lindholm LH, Hansson L, Schersten B, Ekbom T, Wester PO. Morbidity and mortality in the Swedish trial in old patients with hypertension (STOP-hypertension). Lancet. 1991;338:1281–5.

Verdecchia P, Staessen JA, Angeli F, De Simone G, Achilli A, Ganau A, et al. Usual vs. tight control of systolic blood pressure in nondiabetic patients with hypertension (cardio-sis): an open-label randomized trial. Lancet. 2009;374:525–33.

Lewis EJ, Hunsicker LG, Clarke WR, Berl T, Pohl MA, Lewis JB, et al. Renoprotective effect of the angiotensin-receptor antagonist irbesartan in patients with nephropathy due to type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:851–60.

The NAVIGATOR Study Group. Effect of valsartan on the incidence of diabetes and cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1477–90.

Imai E, Chan JC, Ito S, Yamasaki T, Kobayashi F, Haneda M, Makino H for the ORIENT Study Investigators. Effects of olmesartan on renal and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes with overt nephropathy: a multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled study. Diabetologia. 2011;54:2978–86.

The PEACE Trial Investigators. Angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibition in stable coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2058–68.

Thomopoulos C, Parati G, Zanchetti A. Effects of blood pressure lowering on outcome incidence in hypertension. 5. Head-to-head comparisons of various classes of antihypertensive drugs—overview and meta-analyses. J Hypertens. 2015;33:1321–41.

Jamerson K, Weber MA, Bakris GL, Dahlöf B, Pitt B, Shi V, et al. Benazepril plus amlodipine or hydrochlorothiazide for hypertension in high-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2417–28.

ALLHAT Officers and Coordinators for the ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group. Major outcomes in high-risk hypertensive patients randomized to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or calcium channel blocker vs diuretic: the Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT). JAMA. 2002;288:2981–97.

Wing LM, Reid CM, Ryan P, Beilin LJ, Brown MA, Jennings GL, et al. A comparison of outcomes with angiotensin-converting–enzyme inhibitors and diuretics for hypertension in the elderly. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:583–92.

Matsuzaki M, Ogihara T, Umemoto S, Rakugi H, Matsuoka H, Shimada K, et al. Prevention of cardiovascular events with calcium channel blocker-based combination therapies in patients with hypertension: a randomized controlled trial. J Hypertens. 2011;29:1649–59.

Brown MJ, Palmer CR, Castaigne A, de Leeuw PW, Mancia G, Rosenthal T, et al. Morbidity and mortality in patients randomised to double-blind treatment with a long-acting calcium-channel blocker or diuretic in the International Nifedipine GITS study: Intervention as a Goal in Hypertension Treatment (INSIGHT). Lancet. 2000;356:366–72.

Borhani NO, Mercuri M, Borhani PA, Buckalew VM, Canossa-Terris M, Carr AA, et al. Final outcome results of the Multicenter Isradipine Diuretic Atherosclerosis Study (MIDAS). A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1996;276:785–91.

National Intervention Cooperative Study in Elderly Hypertensives Study Group. Randomized double-blind comparison of a calcium antagonist and a diuretic in elderly hypertensives. Hypertension. 1999;34:1129–33.

Zanchetti A, Agabiti Rosei E, Dal Palù C, Leonetti G, Magnani B, Pessina A, et al. The Verapamil in Hypertension and Atherosclerosis Study (VHAS): results of long-term randomized treatment with either verapamil or chlorthalidone on carotid intima-media thickness. J Hypertens. 1998;16:1667–76.

Wilhelmsen L, Berglund G, Elmfeldt D, Fitzsimons T, Holzgreve H, Hosie J, et al. Beta-blockers versus diuretics in hypertensive men: main results from the HAPPHY trial. J Hypertens. 1987;5:561–72.

Dahlöf B, Sever PS, Poulter NR, Wedel H, Beevers DG, Caulfield M, et al. Prevention of cardiovascular events with an antihypertensive regimen of amlodipine adding perindopril as required versus atenolol adding bendroflumethiazide as required, in the Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial-Blood Pressure Lowering Arm (ASCOT-BPLA): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;366:895–906.

Dahlöf B, Devereux RB, Kjeldsen SE, Julius S, Beevers G, de Faire U, et al. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in the Losartan Intervention for Endpoint Reduction in Hypertension Study (LIFE): a randomised trial against atenolol. Lancet. 2002;359:995–1003.

UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group. Efficacy of atenolol and captopril in reducing risk of macrovascular and microvascular complications in type 2 diabetes: UKPDS 39. Br Med J. 1998;317:713–20.

Ogihara T, Nakao K, Fukui T, Fukiyama K, Ueshima K, Oba K, et al. Effects of candesartan compared with amlodipine in hypertensive patients with high cardiovascular risks: candesartan antihypertensive survival evaluation in Japan trial. Hypertension. 2008;51:393–8.

Black HR, Elliott WJ, Grandits G, Grambsch P, Lucente T, White WB, et al. Principal results of the Controlled Onset Verapamil Investigation of Cardiovascular End Points (CONVINCE) trial. JAMA. 2003;289:2073–82.

Yui Y, Sumiyoshi T, Kodama K, Hirayama A, Nonogi H, Kanmatsuse K, et al. Comparison of nifedipine retard with angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors in Japanese hypertensive patients with coronary artery disease: the Japan Multicenter Investigation for Cardiovascular Diseases-B (JMIC-B) randomized trial. Hypertens Res. 2004;27:181–91.

Hansson L, Hedner T, Lund-Johansen P, Kjeldsen SE, Lindholm LH, Syvertsen JO, et al. Randomised trial of effects of calcium antagonists compared with diuretics and beta-blockers on cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in hypertension: the Nordic Diltiazem (NORDIL) study. Lancet. 2000;356:359–65.

Estacio RO, Jeffers BW, Hiatt WR, Biggerstaff SL, Gifford N, Schrier RW. The effect of nisoldipine as compared with enalapril on cardiovascular outcomes in patients with non-insulin-dependent diabetes and hypertension. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:645–52.

Schrader J, Lüders S, Kulschewski A, Hammersen F, Plate K, Berger J, et al. Morbidity and mortality after stroke, eprosartan compared with nitrendipine for secondary prevention: principal results of a prospective randomized controlled study (MOSES). Stroke. 2005;36:1218–26.

Muramatsu T, Matsushita K, Yamashita K, Kondo T, Maeda K, Shintani S, et al. Comparison between valsartan and amlodipine regarding cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in hypertensive patients with glucose intolerance: NAGOYA HEART study. Hypertension. 2012;59:580–6.

Julius S, Kjeldsen SE, Weber M, Brunner HR, Ekman S, Hansson L, et al. Outcomes in hypertensive patients at high cardiovascular risk treated with regimens based on valsartan or amlodipine: the VALUE randomised trial. Lancet. 2004;363:2022–31.

ONTARGET Investigators. Telmisartan, ramipril, or both in patients at high risk for vascular events. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1547–59.

Hansson L, Lindholm LH, Niskanen L, Lanke J, Hedner T, Niklason A, et al. Effect of angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibition compared with conventional therapy on cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in hypertension: the Captopril Prevention Project (CAPPP) randomised trial. Lancet. 1999;353:611–6.

Nakamura T, Kanno Y, Takenaka T, Suzuki H. Efficacy of candesartan on outcome in Saitama trial group. An angiotensin receptor blocker reduces the risk of congestive heart failure in elderly hypertensive patients with renal insufficiency. Hypertens Res. 2005;28:415–23.

Acknowledgments

The data, concepts, and figures reported in this chapter are largely taken from an original article published by the authors in the Journal of Hypertension [3]. Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc., is thanked for permission.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Thomopoulos, C., Zanchetti, A. (2019). Blood Pressure-Lowering Treatment and the Prevention of Heart Failure: Differences and Similarities of Antihypertensive Drug Classes. In: Dorobantu, M., Mancia, G., Grassi, G., Voicu, V. (eds) Hypertension and Heart Failure. Updates in Hypertension and Cardiovascular Protection. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-93320-7_18

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-93320-7_18

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-93319-1

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-93320-7

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)