Abstract

Diabetes is a chronic disease causing tremendous burden on people worldwide. In the 2017 Standards of Medical Care for Diabetes, the American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommends the assessment and integration of psychosocial factors such as depression and diabetes distress into initial and routine patient care to improve outcomes and overall quality of life for patients with diabetes. Psychological conditions, such as depression, distress and stress, serious psychological distress, fatalism, self-efficacy, and social support influence diabetes-related self-management and outcomes and should be incorporated into clinical care practices, addressed in research interventions, and considered in policy implementations. These factors are important to consider as they can significantly impact glycemic control and other outcomes in adults with diabetes. Integrating behavioral and physical care for patients with diabetes will take a coordinated effort, focused on systematic screening, clear treatment pathways, and ongoing monitoring. However, efforts to integrate care have promise to better address the healthcare goals of providing patient-centered care, decreasing both morbidity and cost, and increasing satisfaction with care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Burden of Disease

Diabetes is a chronic disease causing tremendous burden on people worldwide. It is characterized by high levels of blood glucose due to poor or no insulin production, insulin resistance or improper use of insulin, or a combination of both (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 2014). In the United States, approximately 29.1 million people (9.3% of the population) have diabetes (CDC, 2014). Of those who have diabetes, over 8 million (27.8%) remain undiagnosed (CDC, 2014). In US adults 20 years of age and older, nearly 30 million have diabetes, affecting 14% of men and 11% of women (CDC, 2014). Of this same group, approximately 1.7 million new cases are diagnosed annually, and an estimated 86 million have prediabetes (CDC, 2014). Racial and ethnic minority groups in the United States including American Indians/Alaska Natives (15.9%), non-Hispanic Blacks (13.2%), Hispanics (12.8%), and Asian Americans (9.0%) have a higher disease burden of diabetes compared to non-Hispanic Whites (7.6%) (CDC, 2014).

Type 1 and type 2 diabetes are the most common forms, with type 2 diabetes accounting for 90–95% of all cases in adults (CDC, 2014). While type 1 diabetes typically has an earlier onset (mid-teens) and occurs as a result of an immune-mediated destruction of beta cells within the pancreas, type 2 diabetes occurs later in life and, often times, is preventable by eating healthy, being physically active, monitoring blood sugar levels, taking medications, reducing risks, problem solving, and coping (American Academy of Diabetes Educators (AADE), 2017; CDC, 2014). For those at risk of developing type 2 diabetes, factors such as older age, family history, obesity, physical inactivity, race/ethnicity, and a prior diagnosis of gestational diabetes are associated with increased likelihood of developing diabetes (CDC, 2014).

Diabetes affects many organ systems within the body, accounting for significant morbidity and mortality. It is associated with heart disease and stroke, kidney disease and failure, blindness, and lower-limp amputations (CDC, 2014). Uncontrolled diabetes results in notable microvascular complications such as retinopathy, nephropathy, and neuropathy (CDC, 2014). It is the seventh leading cause of death , resulting in death rates 1.5 times higher for adults with diabetes compared to adults without diabetes (CDC, 2014). Finally, total direct and indirect costs associated with diabetes are $245 billion, where approximately $70 is due to disability, losses from work, and premature death (CDC, 2014). Average medical expenditures for people with diabetes more than double those without diabetes (CDC, 2014).

Behavioral Aspects of Diabetes

In the 2017 Standards of Medical Care for Diabetes, the American Diabetes Association (ADA ) recommends the assessment and integration of psychosocial factors such as depression and diabetes distress into initial and routine patient care to improve outcomes and overall quality of life for patients with diabetes (American Diabetes Association (ADA), 2017). The American Academy of Diabetes Educators recommends coping as one of the essential self-care behaviors needed to manage the daily challenges of diabetes. Diabetes can affect people both mentally and physically, impacting their behaviors and adherence to recommended treatment plans. Psychological conditions such as depression, distress and stress, serious psychological distress, fatalism, self-efficacy, and social support can all impact diabetes and must be considered as a part of routine care for adults with diabetes (ADA, 2017; Young-Hyman et al., 2016).

Depression

Like diabetes, depression is a major global health concern. The term “depression” can encompass an array of conditions including major or clinical depression, depressive symptoms, or depressive disorders (Egede, Grubaugh, & Ellis, 2010). Depression, or major depression, is a clinical condition characterized by the presence of a depressed mood and anhedonia within the same 2-week period and the presence of any five of the following symptoms: (1) significant unintentional weight loss or weight gain, (2) insomnia or hypersomnia, (3) psychomotor agitation or retardation, (4) poor concentration, (5) fatigue or loss of energy, (6) feelings of worthlessness or excessive guilt, and (7) suicidal ideation (Egede & Ellis, 2010b). Depressive disorders include major depression, minor depression, and dysthymia (Egede et al., 2010), and depressive symptoms encompass a variety of signs such as mood and cognition changes, anxiety levels, sleep and eating patterns, weight changes, and energy levels (Rush et al., 1986). A history of depression, a previous or current diagnosis of depression , and the use of antidepressants are all risk factors for the development of type 2 diabetes, a risk that is compounded when other risks (i.e., positive family history, obesity, etc.) are present (ADA, 2017).

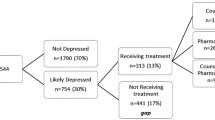

Previous evidence suggests there is a relationship between diabetes and depression, estimating that 25% of people diagnosed with diabetes also have depressive symptomatology (Fisher et al., 2012). Having a diagnosis of diabetes increases the likelihood of receiving a diagnosis of depression (Egede et al., 2016). Recent data estimates 11% of individuals with diabetes also have comorbid major depression, and 45% of adults with diabetes have undiagnosed depression (Egede et al., 2016). Similarly, more than 30% of adults with diabetes have a depressive disorder or depressive symptomatology (Egede et al., 2016). It is noteworthy to mention that the ADA now lists depression as a comorbid condition for diabetes (ADA, 2017).

Diabetes Distress and Stress

Diabetes distress results when significant and negative psychological reactions occur, specific to the burden of managing and living with diabetes, for instance, concerns about disease management, support, emotional burden, and access to care (ADA, 2017). It presents as concealed feelings and emotions that result secondary to stressing and worrying about the complexities of diabetes management (Fisher et al., 2013; Gonzalez, Fisher, & Polonsky, 2011). Often neglected by providers, since it differs from traditional psychological disorders such as clinical depression and dysthymia, diabetes distress has been linked to poor self-efficacy and self-management (Fisher et al., 2013). Evidence suggests diabetes distress significantly impacts clinical outcomes such as glycemic control and behaviors such as medication, diet, and exercise adherence, resulting in poorer glycemic control (ADA, 2017; Egede & Dismuke, 2012; Fisher et al., 2010; Fisher et al., 2010; 2013).

The prevalence of diabetes distress is estimated to be 18–45% with an incidence of 38–48% over an 18-month period (ADA, 2017). In individuals with type 2 diabetes alone, the prevalence is believed to be as high as 45% (Fisher, Hessler, Polonsky, & Mullan, 2012). Because of its distinction and association with poorer outcomes, the management of diabetes distress warrants evaluation and treatment by a mental health provider or behavioral health specialist (ADA, 2017; Fisher et al., 2013). The ADA recommends patients be informed about diabetes distress upon diagnosis, and educated about the possible impact it may have on self-management and overall health (ADA, 2017). Counseling should be provided to help distinguish it from traditional psychological conditions, and concerns associated with self-management that are responsible for higher levels of diabetes distress should be identified and addressed accordingly (ADA, 2017).

There is a widespread and common belief that stress negatively and adversely impacts health. This belief is supported by evidence suggesting stress as a barrier to effective diabetes self-management, resulting in poor outcomes (Hilliard et al., 2016; Surwit, Schneider, & Feinglos, 1992). Stress has been shown to have an environmental, psychological, and biological role in disease development and adverse outcomes (Kelly & Ismail, 2015).

Serious Psychological Distress

Serious psychological distress (SPD) is a general measure of psychological distress found to have a strong, negative association with health (Egede & Dismuke, 2012). Specifically, SPD involves severe distress and is often used as a screening mechanism for serious mental illness, such as major depression that lasts a minimum of 12 months (Winchester, Williams, Wolfman, & Egede, 2016). People with diabetes are often diagnosed with comorbid conditions such as depression and anxiety causing SPD to occur (Shin, Chiu, Choi, Cho, & Bang, 2012). Given the associated mental health problems, SPD often causes significant impairments in social, occupational, and school functioning and requires treatment (Weissman, Pratt, Miller, & Parker, 2015). SPD was associated with significantly higher health expenditures and higher utilization in US adults (Dismuke & Egede, 2011). In addition, even after controlling for depression, SPD significantly diminished quality of life in individuals with diabetes (Dismuke, Hernandez-Tejada, & Egede, 2014).

According to the data from the National Health Interview Survey between 2009 and 2013, women are more likely than men to have SPD, and middle-aged adults (45–64 years) are more likely to have SPD compared to younger (18–44 years) and older (≥65 years) adults, who have the lowest prevalence of occurrence (Weissman et al., 2015). The percentage of non-Hispanic White adults with SPD is lower than the percentage of non-Hispanic Blacks and Hispanic adults with SPD, after adjusting for age (Weissman et al., 2015). Approximately 8.7% of adults with incomes below the federal poverty level have SPD (compared to 1.2% with incomes at or above the 400% poverty level), while adults with SPD are more likely to be uninsured compared to those without SPD (Weissman et al., 2015). In addition, adults with SPD are approximately two times more likely to have diabetes and cardiovascular disease compared to adults without SPD (Shin et al., 2012; Weissman et al., 2015).

Diabetes Fatalism

Diabetes fatalism is a newer construct, conceptualized in recent years from the construct of fatalism, or the principle that events are fixed in advance, rendering human beings powerless to change them (Egede & Bonadonna, 2003; Egede & Ellis, 2010a). Diabetes fatalism is defined as “a complex psychological cycle characterized by perceptions of despair (emotional distress), hopelessness (poor coping), and powerlessness (poor self-efficacy) (Egede & Ellis, 2010a, 2010b). Similar to depression and diabetes distress, diabetes fatalism has been shown to influence diabetes outcomes, resulting in inadequate self-care, poor glycemic control, and decreased quality of life (Egede & Bonadonna, 2003; Egede & Ellis, 2010a, 2010b; Osborn, Bains, & Egede, 2010; Walker et al., 2012). A series of studies have found that accounting for depression and social support removes the significant association between diabetes fatalism and outcomes, suggesting these are important factors when considering how to decrease fatalistic attitudes in patients with diabetes (Asuzu, Walker, Williams, & Egede, 2017; Egede & Osborn, 2010; Osborn et al., 2010).

Self-Efficacy

Self-efficacy is defined as an individual’s confidence in his or her abilities to perform specific behaviors needed to achieve a specified goal (Al-Khawaldeh, Al-Hassan, & Froelicher, 2012; Gao et al., 2013; Sousa, Zauszniewski, Musil, Lea, & Davis, 2005). Evidence suggests self-efficacy has an independent relationship with glycemic control (Walker, Gebregziabher, Martin-Harris, & Egede, 2014) and can be influenced by multiple psychosocial factors including depression and diabetes distress (Devarajooh & Chinna, 2017). Self-efficacy is considered a critical component for adequate self-management in diabetes care (Al-Khawaldeh et al., 2012; Gao et al., 2013) such that as self-efficacy increases, self-management improves, resulting in better glycemic control (Sousa et al., 2005). To achieve successful self-management, self-efficacy is needed to maintain healthy behaviors, improve decision-making, and promote positive well-being (Sousa et al., 2005). Previous research by Sousa et al. suggests that women, shorter disease duration, older age, non-Hispanic Black race, and a diagnosis of type 1 diabetes are associated with better self-efficacy, therefore, better diabetes-related outcomes (Sousa et al., 2005).

Social Support

Social support is a perception of acceptance, provision, and assistance from formal and informal relationships with others (Strom & Egede, 2012). It is also the realization that support is actually received from another individual (Strom & Egede, 2012). Social support can present in various ways including emotional, tangible, and informational and through companionship (Strom & Egede, 2012; van Dam et al., 2004). Emotional support occurs when feelings of validation and worth are expressed (Strom & Egede, 2012; van Dam et al., 2004). Tangible support rallies around the concept of provision such as assistance with finances, goods, and services (Strom & Egede, 2012; van Dam et al., 2004). The distribution of information, advice, and guidance to assist with problem solving, goal setting, and decision-making are perceived as informational support (Strom & Egede, 2012; van Dam et al., 2004). The sense of belonging and the presence of companions for engaging in activities describe companionship (Strom & Egede, 2012; van Dam et al., 2004). These perceptions of support can be perceived as positive (beneficial) or negative (harmful) and can be received from different sources including family members, friends and peers, providers, and organizations (Stopford, Winkley, & Ismail, 2013; Strom & Egede, 2012). Higher levels of social support are often associated with better glycemic control and outcomes, whereas lower levels of support are associated with increased mortality and adverse complications (Strom & Egede, 2012). Given the complex nature of diabetes management, evidence suggests social support serves as a facilitator for improved self-management and health outcomes in chronic diseases such as diabetes (Stopford et al., 2013; Strom & Egede, 2012) through either a buffering or direct effect (Cohen & Wills, 1985; Thoits, 1985); however, the evidence has been inconclusive.

Impact of Behavioral Aspects of Diabetes on Processes and Outcomes

Impact on Self-Care

Eating healthy , monitoring blood glucose levels, being physically active, and taking medications as prescribed are all important and necessary processes in self-care. Behavioral aspects of diabetes contribute to self-care and management, such that higher levels of depression, diabetes distress, and perceived stress, for example, typically lead to poorer self-care, while higher levels of social support and self-efficacy are often associated with better self-care (Asuzu et al., 2017; Fisher et al., 2013; Walker et al., 2012, 2014). In the Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes, the ADA reports that higher levels of diabetes distress significantly impact self-care behaviors such as medical adherence and are associated with poorer nutritional intake and physical activity (ADA, 2017). In a study by Fisher et al., reductions in diabetes distress resulted in significant improvements in self-care behaviors such as eating healthy, being physically active, and adhering to prescribed medication regimens (Fisher et al., 2013). Furthermore, poor medication adherence and self-care, independent of depression, have been facilitated by fatalism (Walker et al., 2012). Finally, evidence suggests patients with comorbid diabetes and SPD have higher odds of 14 or more days of limited physical activity compared to those with diabetes only (McKnight-Eily et al., 2009).

Impact on Process and Quality of Care

Quality of care is important in disease management, especially so for a chronic disease such as diabetes where patient and provider factors contribute to the complex process of management. A1c testing, cholesterol testing, annual foot examinations, and preventive services such as influenza and pneumonia vaccinations, diabetes treatment, and diabetes education classes are a few examples of processes of care that contribute to the quality of care in diabetes management (Egede et al., 2010; Walker et al., 2014). Evidence suggests that processes of care are often mediated by behavioral aspects of diabetes and have an impact on outcomes. For example, social support has been found to have a significant and indirect relationship on glycemic control, a relationship mediated by processes of care (Walker et al., 2014). In addition, adults with diabetes and depression were less likely to receive preventive care, such as mammograms, and were less likely to perceive their health as good or report being satisfied with life (Egede et al., 2010). In general, patient satisfaction has been shown to improve medication adherence, patient-provider communication, and overall health outcomes (Schoenfelder, 2012). In adults with diabetes, satisfaction has been associated with glycemic control, treatment plan management, and treatment evaluations (Williams, Pollack, & Dibonaventura, 2011).

Impact on Clinical Outcomes

Clinical outcomes such as glycosylated hemoglobin A1c (A1c), blood pressure (BP), and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) are important to consider when assessing the relationship between behavioral aspects and diabetes. Measuring the A1c is particularly important in diabetes management as it offers information about glucose control over the prior 3 months of testing (ADA, 2017). Behavioral aspects of diabetes have been shown to have an impact on clinical outcomes, particularly the A1c, when assessing glycemic control in persons with diabetes. Depression has been associated with poor glycemic control in patients with both type 1 and type 2 diabetes (Egede et al., 2010). Walker et al. (2014) report that higher fatalism, higher diabetes distress, and lower self-efficacy are directly associated with lower HbA1c (Walker et al., 2014). Hilliard et al. suggest that stress is strongly associated with A1c, especially in minorities and youth, two vulnerable populations with a disproportionate stress burden (Hilliard et al., 2016).

Impact on Cost and Utilization

A comorbid diagnosis of diabetes and a psychological condition such as depression is associated with increased morbidity and mortality (Egede et al., 2016). In a study to access the association between comorbid depression and healthcare utilization and expenditures, Egede et al. report increased healthcare use and expenditures for individuals diagnosed with both depression and diabetes (Egede, Zheng, & Simpson, 2002). Simon et al. suggest that depression is associated with a 50–75% increase in healthcare expenditures for people with diabetes (Simon et al., 2005). Medical conditions including hypertension and coronary heart disease and psychological and behavioral conditions such as depression are predicted to be stronger contributors to future healthcare expenditures for adults with diabetes (Gilmer et al., 2005). Recent estimates suggest expenditures are approximately $5000 higher for symptomatic depression in adults with diabetes (Egede et al., 2016). SPD has also been associated with higher healthcare expenditures and utilization in adults with diabetes (Egede & Dismuke, 2012). Finally, individuals diagnosed with both medical and psychological conditions simultaneously often have higher utilization of services (Egede et al., 2002; Puyat, Kazanjian, Wong, & Goldner, 2017).

Pathways Linking Behavioral Health with Diabetes Outcomes

In an effort to better understand how to design care to address behavioral health of individuals with diabetes, significant work has been conducted to understand the mechanisms and pathways linking behavioral health with diabetes outcomes. These pathways include both biological and behavioral influences and link a number of psychosocial factors to diabetes self-management, glycemic control, and overall quality of life for people with diabetes.

Depression

Diabetes and depression co-occur twice as frequently as chance would predict and lead to significantly increased costs, without major improvements in outcomes (Egede, 2005; Egede et al., 2016; Holt et al., 2014a, 2014b). As such, substantial work has been done to understand the relationship both in terms of pathways linking the two diseases and the direction of causation. Epidemiologic studies show the association is bi-directional, though depression as a risk factor for diabetes is the stronger relationship (Andreoulakis, Hyphantis, Kandylis, & Iacovides, 2012; Carnethon, Kinder, Fair, Stafford, & Fortmann, 2003; Holt et al. 2014a, 2014b). Particularly in older adults, individuals who reported higher depressive symptoms or persistently high symptoms were more likely to develop diabetes, even after controlling for other risk factors (Carnethon et al., 2007). Shared biological and behavioral pathways that predispose individuals for both diabetes and depression have shifted current recommendations from focusing on the direction of association to focusing on the mechanisms common to both (Holt et al. 2014a, 2014b). Four common interrelated biological pathways have been identified, including epigenetic changes, hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis dysfunction, inflammation, and sleep/circadian rhythm disruption (Holt et al., 2014b). Both the external environment, in the form of neighborhoods in which individuals live, and adversity experienced in childhood, as well as the intrauterine environment in which an individual developed, can influence the health behaviors that in turn impact these biological pathways (Holt et al., 2014b). In addition, ongoing research is focused on trying to understand how environmental factors interact with biological pathways resulting in individual vulnerability and resilience (Holt et al., 2014b).

When specifically considering patients with diabetes, independent factors associated with major depressive disorder included demographic variables such as younger age, female sex, lower income, and at least a high school education, as well as behavioral factors such as smoking and perceptions about the influence of diabetes on their health (Egede & Zheng, 2003). There are three major pathways through which comorbid depression is understood to influence diabetes outcomes (Egede, 2005; Piette, Richardson, & Valenstein, 2004). The first pathway is through directly impacting an individual’s quality of life by multiplying the impact of both diseases on physical, social, and role functions (Piette et al., 2004). Diabetes is a psychologically demanding disease, requiring regular problem solving, regime maintenance, and awareness of debilitating complications associated with the disease (Piette et al., 2004). Comorbid depression may exacerbate this mental burden (Holt et al., 2014a; Egede & Zheng, 2003). For example, one study found that individuals with treated type 2 diabetes were at increased risk of developing depressive symptoms over 3 years, while those with untreated diabetes were not (Golden et al., 2008). Psychological stress associated with diabetes management, therefore, is an important factor to consider in addition to depressive symptoms, in the additive impact on outcomes (Golden et al., 2008). The presence of medical comorbidities has also been noted as a factor contributing to comorbid depression in individuals with diabetes, highlighting the psychological impact further complications may have on individuals with diabetes (Andreoulakis et al., 2012).

A second pathway through which depression impacts diabetes outcomes is through decreasing motivation to complete self-management behavior , most particularly through decreasing physical activity (Egede, 2005; Piette et al., 2004). Interventions that promote physical activity have been shown to improve both depressive- and diabetes-related symptoms, suggesting an important focus for patients with comorbid diabetes and depression (Boule, Haddad, Kenny, Wells, & Sigal, 2001). Additional self-care behaviors may also be influenced through a lack of energy, negative thought patterns, and passive coping strategies (Piette et al., 2004). Self-efficacy has been shown to significantly influence completion of self-care behaviors (Walker, Gebregziabher, Martin-Harris, & Egede, 2015). As such, treatment for depression through cognitive behavioral therapy may improve outcomes by addressing dysfunctional beliefs serving as obstacles to better self-care and improved functioning (Piette et al., 2004). Additionally, poor adherence to self-care may be a mutually reinforcing phenomenon, with poor adherence contributing to more depressive symptoms and depressive symptoms then contributing to decreased adherence (Holt et al., 2014a). In a study of individuals with diabetes followed over a 5-year period, self-care behaviors explained a significant amount of the relationship between depressive symptoms at baseline and glycemic control 5 years later (Chiu, Wray, Beverly, & Dominic, 2010). As a result, even low depressive symptoms may have long-term impacts in patients with diabetes (Chiu et al., 2010).

A third pathway involves the impact of depression on the relationship with healthcare providers (Piette et al., 2004). Less satisfactory interactions with providers, including poor communication and unmet expectations, can result in less motivation to engage with the healthcare system (Piette et al., 2004). Simultaneously, providers are more likely to consider patients with depression “difficult” or “less able to cope,” which can influence communication and management (Piette et al., 2004).

Diabetes Distress and Stress

Diabetes distress is common in individuals with diabetes and is both conceptually and practically distinct from depression (Fisher et al., 2010; Young-Hyman et al., 2016). The relationship between distress and the burden of diabetes is independently associated with outcomes, and, often once included in models, removes the independent relationship between depression and glycemic control (Fisher et al., 2010; Gonzalez, Shreck, Psaros, & Safren, 2015; Walker et al., 2014). In fact, in a structured equation model investigating the relationship between diabetes distress, depression, fatalism, and glycemic control, it was diabetes distress, and not depression, that served as the main pathway influencing diabetes outcomes (Asuzu et al., 2017). Distress has been found to have a direct relationship with diabetes self-care and has both a direct and indirect influence on glycemic control (Walker et al., 2014, 2015). The indirect influence has been attributed to adherence to self-care behaviors, through decreased access to patient-centered care and through decreased perceived control over diabetes (Gonzalez et al., 2015; Walker et al., 2014). Additionally, diabetes distress has an equally strong and separate relationship with self-care and glycemic control, highlighting the importance of taking both psychological and behavioral factors into account for comprehensive diabetes care (Asuzu et al., 2017). Investigation of a 12-month intervention aimed at decreasing diabetes distress found that reduction in distress was a significant pathway associated with improved self-management, including physical activity and medication adherence, as well as improved glycemic control (Hessler et al., 2014).

More general perceived stress has also been associated with adherence to self-care, and processes specific to diabetes care, such as diabetes education, but did not show a direct relationship to glycemic control (Walker et al., 2014). In addition, perceived stress may help explain the relationship between environmental factors and diabetes outcomes. For instance, higher levels of stress have been associated with socioeconomic disadvantage (Baum, Garofalo, & Yali, 1999). When investigating patients with type 1 diabetes, it was found that high diabetes-related stress linked socioeconomic disadvantage to a flatter cortisol slope, and these flatter slopes were associated with worse glycemic control (Zilioli, Ellis, Carré, & Slatcher, 2017). In addition, an investigation of pathways between discrimination and quality of life in patients with type 2 diabetes found that perceived stress served as a direct pathway with the mental component of quality of life (Achuko, Walker, Campbell, Dawson, & Egede, 2016). The impact of general stress on health was shown to occupy a central role in the way patients viewed diabetes, whereas healthcare providers and diabetes educators focused on the importance of lifestyle changes and saw stress as a regime management issue (Schoenberg, Drew, Stoller, & Kart, 2005). This difference in how patients and providers view the impact of stress on their outcomes may undermine the patient-provider relationship and limit the ability of the healthcare system to help patients adequately address psychosocial factors impacting their health (Schoenberg et al., 2005).

Mediators and Moderators of the Impact on Diabetes Outcomes

Given the influence of stress and distress on diabetes outcomes, it is not surprising that coping style is considered a possible mediator of behavioral health in individuals with diabetes. Since coping is derived from appraisal of stressors , both general and diabetes-specific stressors may influence diabetes outcomes. Using the Ways of Coping Checklist , one study showed that active coping, avoidance coping, and minimizing the situation all played a role in mediating the relationship between depressive symptoms and health-related quality of life (Huang et al., 2016). Active coping and minimizing the situation had strong negative associations with depressive symptoms; thus, patients may reduce the impact of depression on health-related quality of life through the use of these coping styles (Huang et al., 2016). In patients with type 1 diabetes followed over 1 year, avoidant coping style was shown to lead to diabetes-related distress at a later time, rather than the opposite order (Iturralde, Weissberg-Benchell, & Hood, 2017). Avoidant coping led to worse diabetes outcomes in the future, with blood glucose monitoring and glycemic control fully mediated by distress, and self-reported adherence partially mediated by distress (Iturralde et al., 2017). In a separate analysis, followed over 4 years, active coping predicted better glycemic control, which in turn predicted continued active coping (Luyckx, Seiffge-Krenke, & Hampson, 2010). Alternatively, worse glycemic control predicted avoidant coping later in time (Luyckx et al., 2010). These results suggest that coping skills are an important factor to address for long-term diabetes care.

Social support is an additional factor shown to influence psychological drivers of diabetes outcomes. Theoretical mechanisms for social support’s influence on health include suppression of negative affect, improved immune system functioning, and promoting healthy lifestyle behaviors (Cohen, 1988). Social support has been found to serve as a mediator in the pathway between depression and self-care behaviors, supporting the idea of its impact on negative affect (Egede & Osborn, 2010). In an investigation of the impact of discrimination in patients with diabetes, social support had a direct and indirect effect on the mental component of quality of life (Achuko et al., 2016). The indirect effect of social support was mediated through perceived stress, suggesting social support has an influence on both perceived stress and the mental component of quality of life (Achuko et al., 2016). Social support also showed an indirect association to glycemic control in patients with diabetes, mediated through access to patient-centered care (Walker et al., 2014). And in a study of Chinese adults with type 2 diabetes, patient-provider communication was correlated with social support, suggesting physicians may be an important aspect of support for individuals with diabetes (Gao et al., 2013). Social support’s association with glycemic control has also been shown to be mediated by self-care, supporting the third theoretical mechanism hypothesized by Cohen (Gao et al., 2013). The frequency of using social support resources, both from family and friends, as well as from neighborhoods and communities, was a significant mediator of an intervention designed to increase social support on physical activity, fat consumption, and glycemic control (Barrera Jr, Toobert, Angell, Glasgow, & Mackinnon, 2006). Changes in the extensiveness of social networks also mediated the intervention’s impact on physical activity (Barrera Jr et al., 2006). Interestingly the individuals’ perceived availability of social support was not a mediator of this intervention (Barrera Jr et al., 2006). Contrary to Barrera’s findings, a mediation analysis of the impact of a peer support intervention did not find social support to significantly mediate improvements in glycemic control (Piette, Resnicow, Choi, & Heisler, 2013). However, when investigating moderators, the intervention did have a significant impact in patients with lower social support at baseline, whereas it did not on patients with higher social support levels (Piette et al., 2013). Based on these results, while social support does not appear to have a direct influence on glycemic control , it impacts diabetes outcomes through a variety of pathways, including support received from family, friends, physicians, and communities, and may be an effective tool for improving diabetes care, particularly in those with low levels of support currently.

Models of Care to Address Behavioral Health and Diabetes Outcomes

Fragmented Care in the Context of Diabetes and Behavioral Health

One of the greatest concerns facing the increasingly complex healthcare system is fragmentation of care and lack of continuity (Egede, 2006; Frandsen, Joynt, Rebitzer, & Jha, 2015; Holt et al., 2014a; Hussey et al., 2014). Care often involves multiple providers with no central provider or organization effectively coordinating care (Egede, 2006; Frandsen et al., 2015). Lack of coordination across providers often results in poor outcomes, missed opportunities, and increased costs (Egede, 2006; Frandsen et al., 2015). In individuals with chronic disease, care fragmentation was associated with both higher costs and lower quality of care (Egede, 2006; Frandsen et al., 2015). Lack of continuity has also been associated with higher rates of hospital and emergency department (ED) use, higher rates of complications, and higher cost (Hussey et al., 2014). Even appropriate referrals to sub-specialties for patients with diabetes led to increased fragmentation and higher ED use, suggesting attention to risks and effectiveness of multiple providers is needed when designing systems of care (Liu, Einstadter, & Cebul, 2010). Without adequate coordination and integration across systems, care guidelines requiring referral to additional providers may increase patient risk and cause unnecessary confusion for patients (Liu et al., 2010).

The need for mental health treatment in the context of primary care has led to a call for integrated care systems. Despite efforts to increase integration, recognition and treatment for depression in primary care are insufficient (de Groot, Golden, & Wagner, 2016; Egede, 2006, 2007). In addition, recognition of depression does not always change treatment plans, patients often do not receive sufficient doses or duration of antidepressant medication to achieve remission, and lack of regular monitoring results in discontinuation of medication without provider knowledge or continuation of medications that are not effective (Egede, 2006, 2007; Gilbody, Sheldon, & House, 2008; Unutzer & Ratzliff, 2015).

Incorporating Psychosocial Health into Standards of Care

Healthcare professionals have an important role to play in integrating behavioral health into the care of patients with diabetes. A call for more systematic screening, with defined care pathways for patients that screen positive, has been made for years with limited uptake (de Groot et al., 2016; Egede, 2007; Holt et al., 2014a, 2014b; Piette et al., 2004). Often, screening efforts are opportunistic, rather than systematic, limiting implementation of treatment (de Groot et al., 2016). More recently, a call has been made to assess symptoms of psychosocial factors beyond depression (Young-Hyman et al., 2016). The American Diabetes Association (ADA) published a position statement on psychosocial care for people with diabetes, with a series of recommendations for incorporating psychosocial care into standard of care (Young-Hyman et al., 2016). This includes consideration of psychosocial factors across the life span, assessment of a number of psychosocial factors, and addressing psychosocial problems upon identification (Young-Hyman et al., 2016). Assessment of psychosocial factors may provide a better understanding of reasons for suboptimal glycemic control, rather than assumption. And it is based on nonadherence to self-care behaviors (Young-Hyman et al., 2016). Normalizing the idea that periodic lapses in self-management occur may help patients report problems and discuss diabetes-related and generalized psychological distress at diagnosis and when treatment changes may help ensure patients feel providers understand their lived experience (Young-Hyman et al., 2016). Increasing the recognition that mental and physical health interact and how treatment strategies need to change when dual conditions are present is important for effective care (Piette et al., 2004). Finally, providing care through a multidisciplinary team will help identify high-risk patients and deliver evidence-based therapy (Holt et al., 2014b).

Evidence-Based Integrated Care Approaches

Collaborative care, stepped care, and patient-centered medical homes (PCMH) are all evidence-based systematic efforts to improve coordination of care and satisfaction with care (Unutzer & Ratzliff, 2015). Though related, each has specific principles that define care systems.

Collaborative care has five core principles including patient-centered care incorporating shared care plans, evidence-based care based on credible research, measurement-based treatment to target requiring routine measurements of clinical outcomes and personal goals, population-based care due to each care team sharing a defined group of patients, and accountable care focused on quality care and outcomes (Unutzer & Ratzliff, 2015). Collaborative care teams include interdisciplinary cooperation and include at minimum an actively engaged patient, a primary care provider, a care manager, and a mental health professional (Petrak, Baumeister, Skinner, Brow, & Holt, 2015; Unutzer & Ratzliff, 2015). Psychiatric consults can provide a range of interaction including informal consultations, systematic case reviews, and face-to-face consultations (Unutzer & Ratzliff, 2015). Routine monitoring of outcomes and proactive follow-up with patients are overseen by a care manager, who assists in decision-making support both for the patient and providers (Petrak et al., 2015). A number of collaborative care interventions have been tested in the United States, showing increased satisfaction with care and greater improvements in depressive symptoms up to 1 year posttreatment (Katon et al., 2004; Petrak et al., 2015).

One specific clinical approach for collaborative care is stepped care , which is based on a rationale that treatment is started at low intensity and increased based on systematic reassessment (Katon et al., 2004; Stoop, Nefs, Pommer, Pop, & Pouwer, 2015; Unutzer & Ratzliff, 2015). Stepped care incorporates patient preference and different types and intensities of treatment (Katon et al., 2004). Interventions are provided sequentially based on algorithms and treatment plans with specified cutoffs for transitions to the next step (Petrak et al., 2015). For example, in treatment of comorbid depression with diabetes, if suicidal tendencies do not exist, mild depression treatment can be provided in primary care by informing patients of the link between diabetes and depression, identifying targets for intervention (such as thoughts, activity levels, social interactions, or self-care adherence), and provision of self-help materials (Petrak et al., 2015). If improvement does not occur within 2–4 weeks, treatment should be escalated to psychological or pharmacological treatment (Petrak et al., 2015). It is important to consider whether patients have a history of recurrent depression , as treatment may need to be escalated faster, or offered in combination, such as a combined pharmacological and pharmacotherapy treatment (Petrak et al., 2015). Again, response after 2–4 weeks should be monitored and escalated if improvement is not seen, highlighting the importance of having a behavioral health specialist on the multidisciplinary team to provide insight and treatment options (Petrak et al., 2015).

Patient-centered medical homes (PCMH) is a model of enhanced primary care to address fragmented care and competing interests within the healthcare system (Jortberg, Miller, Gabbay, Sparling, & Dickinson, 2012). PCMH is based on the chronic care model and focuses on patient-centered care, self-management support, patient empowerment, and team-based care (Bojadzievski & Gabbay, 2011). In the context of patients with diabetes, integration of behavioral health is necessary to address high-risk individuals and provide a way to simultaneously address mental and physical health (Jortberg et al., 2012). Similar to collaborative care, PCMH often uses a care manager to coordinate treatment regimens and assist in self-management support (Jortberg et al., 2012). By training care managers in behavioral health, they have the capacity to expand the reach of physicians and address the psychosocial aspects of diabetes care (Jortberg et al., 2012). This can be done through proactive outreach to provide follow-up, support, and scheduled appointments with providers when escalation of treatment is needed (Jortberg et al., 2012).

Training for care managers , integral in both collaborative care and PCMH models, may take multiple approaches. An implementation project to expand collaborative care initiatives found that while the intervention care manager was a diabetes nurse trained in depression care, healthcare sites implementing the program used primary care nurses, mental health professionals cross-trained in diabetes treatment guidelines, or two professionals coordinating care where one was trained to treat diabetes and the other trained to treat depression (Coleman et al., 2017). In the implementation of a collaborative care program at a safety net primary care clinic, with no additional funding for the program, it was found that investment of time and staff was required to reorganize care in order to provide a team-based approach (Chwastiak et al., 2017). A medical assistant provided support for care management by completing outreach phone calls and managing data, which allowed nurses to focus on higher-level tasks required by the patients (Chwastiak et al., 2017). Care managers then provided structured health assessments , education, brief evidence-based behavioral interventions, and conducted weekly systematic caseload reviews (Chwastiak et al., 2017). Use of a stepped care approach allowed patients with mild symptoms to be managed by the nurse case managers, while more serious disorders were primarily handled by the integrated mental health team in primary care (Chwastiak et al., 2017).

Recommendations for Integrated Care

Below are a series of recommendations for effective integrated care. The most evidence has been collected on providing care for patients with diabetes and comorbid depression, and as such, many recommendations are adapted from recommendations for integrated depression care.

First, integrated care should include (1) screening, (2) treatment, and (3) monitoring for relapse and involve a multidisciplinary team with the individual with diabetes at the center of the care process. Use of only one or two of these activities will not result in an efficient and sustainable system of care to meet the complex physical and psychosocial needs of patients with diabetes. Consistent implementation of screening is needed using standardized/validated tools, with systems in place to confirm and offer treatment based on screening results (Egede, 2007; Holt et al., 2014b; Young-Hyman et al., 2016). For example, depression can be screened for by asking if there have been changes in mood, such as little interest or pleasure in doing things or feeling down, depressed, or hopeless, during the past 2 weeks or between visits (Petrak et al., 2015; Young-Hyman et al., 2016). Stress and diabetes distress can be initially screened by asking if the patient feels overwhelmed or stressed by life or diabetes management (Young-Hyman et al., 2016). Positive responses would then be followed by standardized and validated measures, for example, use of the PHQ-9 for affirmative depression responses, use of the Diabetes Distress Scale for distress, discussion of treatment options, and referral to a behavioral health provider for assessment as needed (Petrak et al., 2015, Young-Hyman et al., 2016). Positive screening should be followed with a clear treatment pathway, and treatments should include a stepped approach where more intensive management can be offered when required (Holt et al., 2014a, b; Petrak et al., 2015). Ideally, behavioral/mental health providers should be embedded in primary care and diabetes care settings to increase care coordination; however, primary care providers can also identify behavioral/mental health providers that are knowledgeable about the psychosocial aspects of diabetes to use for referrals (Young-Hyman et al., 2016). In addition, if appropriate, identifying a support person to include in care decisions may help identify, prevent, and resolve psychosocial problems (Young-Hyman et al., 2016). Incorporating a nurse case manager in care is recommended for treatment of comorbid depression but may also assist in addressing other psychosocial concerns, such as identifying community resources and providing stress management techniques (Holt et al., 2014a; Young-Hyman et al., 2016). Finally, monitoring after treatment to prevent relapse and provide ongoing support is an important aspect of integrated care. In a study of a culturally tailored collaborative care program, relapse prevention strategies, including symptom monitoring, behavioral activation, and problem-solving plans, were credited with the sustained impact over time (Ell et al., 2011). In a study of stepped care approach, the majority of patients experienced recurrent symptoms in the monitoring phase that may have been missed without continued follow-up (Stoop et al., 2015).

Second, a number of psychosocial concerns should be included in screening, treatment, and ongoing monitoring as part of routine diabetes management, including diabetes distress, social support, and self-efficacy. Through efforts to incorporate clear guidelines on how to address these factors, healthcare professionals can better moderate the psychological burden of diabetes through psychosocial support . Based on the evidence, multiple causative pathways likely operate within the context of behavioral health and diabetes outcomes, with personal behavioral or coping styles moderating the impact on disease management and health outcomes over time (Hessler et al., 2014). Recognition of different psychosocial factors, such as perceived stress, self-efficacy, or social support resources, may help providers better understand the patient’s social circumstances and their decisions to adhere or not adhere to recommendations (Schoenberg et al., 2005; Young-Hyman et al., 2016). In addition, screening for both depression and diabetes distress will help address concerns of the potential overlap between diabetes-related symptoms and depression symptoms and ensure appropriate care is planned based on results (Petrak et al., 2015). Linking treatment to community resources may also help in increasing provision of social support and addressing concerns beyond the healthcare system (Holt et al., 2014b). This more comprehensive view of the patient will then assist in better matching care recommendations to the context of the patient’s life, increasing provision of truly patient-centered care.

Third, a combination of pharmacological and psychotherapy treatment approaches is recommended for effective care (Katon et al., 2004; Petrak et al., 2015). Patients may prefer either medications or psychotherapy and may accept one service, while refusing the other (Piette et al., 2004). The most effective treatment for depression and diabetes control has been seen in a combination of psychotherapeutic intervention and self-management training (Andreoulakis et al., 2012; de Groot et al., 2016; Holt et al., 2014a). Common psychological interventions include cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), problem solving, interpersonal therapy, motivational interviewing, and counseling (de Groot et al., 2016). Cognitive behavioral treatments are particularly promising as a psychotherapy to address both behavioral health and diabetes-specific behavioral needs, as they target perceptions and behaviors likely to improve both diabetes self-care and psychological factors (Piette et al., 2004). Patients with diabetes who are struggling to maintain adequate glycemic control may be assisted through a program teaching different coping styles to help reduce depressive symptoms and address negative thought patterns that limit their ability to complete self-care behaviors (Huang et al., 2016; Piette et al., 2004). Avoidance processes inherent in avoidant coping styles are a central target in acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) and therefore may be ideal to use with patients exhibiting avoidant coping styles (Iturralde et al., 2017). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy has been shown to be effective in addressing anxiety and could be targeted to address diabetes-specific anxieties such as fear of complications and hypoglycemia (de Groot et al., 2016). Physical activity should also be promoted as it is an important component of effective diabetes management and has been shown to improve depressive symptoms (Holt et al., 2014b; Piette et al., 2004). Contextual factors, including cultural differences , should be taken into account given reporting of depression may vary across racial/ethnic groups, and experiences, such as discrimination, may decrease reporting of symptoms and adherence to treatment (de Groot et al., 2016; Holt et al., 2014b).

Fourth, success should be measured by a combination of physical, behavioral, and psychological outcomes (Petrak et al., 2015). Similar to research showing focus only on physical aspects of diabetes does not result in optimal outcomes, and a focus only on improvements in mental health will not likely result in optimal care (Holt et al., 2014a; Katon et al., 2004). Including monitoring of psychosocial factors and self-care behaviors will also provide a more comprehensive understanding of patient factors and inform care plans (Holt et al., 2014b; Young-Hyman et al., 2016). Stepped approaches can facilitate initial target outcomes, such as depressive symptoms or tobacco use, and followed by subsequent goals focusing on health-related quality of life, psychosocial functioning, or coping in a way that is economically sustainable (Holt et al., 2014b; Petrak et al., 2015). In addition, simultaneous consideration of cognitive factors, diabetes management, and glycemic control can improve understanding of the psychosocial needs of patients facing the demands of diabetes to ensure long-term success (Gonzalez et al., 2015; Petrak et al., 2015). Monitoring the results of treatment is necessary to ensure remission of psychological symptoms and guide stepped care approaches (Petrak et al., 2015).

Finally, new approaches that leverage the use of technology to increase reach and improve care should be investigated and implemented in clinical settings. The use of clinical information systems to offer reminders to providers and the use of mobile phone applications to offer reminders to patients can both be used to increase awareness of evidence-based guidelines (Egede, 2007). Telephone care is an effective strategy for helping patients manage both depression and diabetes and can be used for education, behavioral monitoring, and evaluation of changes (Egede, Williams, Voronca, Gebregziabher, & Lynch, 2017; Piette et al., 2004). Extending the reach of collaborative care through telemedicine, patient registries, and mHealth technologies may provide a way to address both prevention and treatment at a population level (Holt et al., 2014b; Petrak et al., 2015).

Conclusions

Psychological conditions influence diabetes-related self-management and outcomes and should be incorporated into clinical care practices, addressed in research interventions, and considered in policy implementations. These factors are important to consider as they can significantly impact glycemic control and other outcomes in adults with diabetes. Integrating behavioral and physical care for patients with diabetes will take a coordinated effort, focused on systematic screening, clear treatment pathways, and ongoing monitoring. However, efforts to integrate care have promise to better address the healthcare goals of providing patient-centered care, decreasing both morbidity and cost, and increasing satisfaction with care.

References

Achuko, O., Walker, R. J., Campbell, J. A., Dawson, A. Z., & Egede, L. E. (2016). Pathways between discrimination and quality of life in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Technology & Therapeutics, 18(3), 1–8.

Al-Khawaldeh, O. A., Al-Hassan, M. A., & Froelicher, E. S. (2012). Self-efficacy, self-management, and glycemic control in adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Journal of Diabetes and Its Complications, 26, 10–16.

American Academy of Diabetes Educators. (2017). AADE7 self-care behaviors. Accessible at: https://www.diabeteseducator.org/patient-resources/aade7-self-care-behaviors. Accessed 28 Apr 2017.

American Diabetes Association. (2017). Lifestyle management. Sec. 4. In standards of medical care in diabetes, 2017. Diabetes Care, 40(Suppl. 1), S33–S43.

Andreoulakis, E., Hyphantis, T., Kandylis, D., & Iacovides, A. (2012, July). Depression in diabetes mellitus: a comprehensive review. Hippokratia, 16(3), 205–214.

Asuzu, C. C., Walker, R. J., Williams, J. S., & Egede, L. E. (2017, January). Pathways for the relationship between diabetes distress, depression, fatalism and glycemic control in adults with type 2 diabetes. Journal of Diabetes and its Complications, 31(1), 169–174.

Barrera, M., Jr., Toobert, D. J., Angell, K. L., Glasgow, R. E., & Mackinnon, D. P. (2006, May). Social support and social-ecological resources as mediators of lifestyle intervention effects for type 2 diabetes. Journal of Health Psychology, 11(3), 483–495.

Baum, A., Garofalo, J. P., & Yali, A. N. N. (1999). Socioeconomic status and chronic stress: does stress account for SES effects on health? Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 896, 131–144.

Bojadzievski, T., & Gabbay, R. A. (2011). Patient-centered medical home and diabetes. Diabetes Care, 34(4), 1047–1053.

Boule, N. G., Haddad, E., Kenny, G. P., Wells, G. A., & Sigal, R. J. (2001). Effects of exercise on glycemic control and body mass in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. Journal of the American Medical Association, 286(10), 18–1227.

Carnethon, M. R., Biggs, M. L., Barzilay, J. I., Smith, N. L., Vaccarino, V., Bertoni, A. G., et al. (2007, April 23). Longitudinal association between depressive symptoms and incident type 2 diabetes mellitus in older adults: the cardiovascular health study. Archives of Internal Medicine, 167(8), 802–807.

Carnethon, M. R., Kinder, L. S., Fair, J. M., Stafford, R. S., & Fortmann, S. P. (2003, September). Symptoms of depression as a risk factor for incident diabetes: findings from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Epidemiologic Follow-up study, 1971–1992. American Journal of Epidemiology, 158(5), 416–423.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014). National diabetes statistics report: Estimates of diabetes and its burden in the United States, 2014. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Chiu, C. J., Wray, L. A., Beverly, E. A., & Dominic, O. G. (2010, January). The role of health behaviors in mediating the relationship between depressive symptoms and glycemic control in type 2 diabetes: a structural equation modeling approach. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 45(1), 67–76.

Chwastiak, L. A., Jackson, S. L., Russo, J., DeKeyser, P., Keifer, M., Belyeu, B., et al. (2017). A collaborative care team to integrate behavioral health care and treatment of poorly-controlled type 2 diabetes in an urban safety net primary care clinic. General Hospital Psychiatry, 44, 10–15.

Cohen, S. (1988). Psychosocial models of the role of social support in the etiology of physical disease. Health Psychology, 7, 269–297.

Cohen, S., & Wills, T. A. (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 98, 310–357.

Coleman, K. J., Magnan, S., Neely, C., Solberg, L., Beck, A., Trevis, J., Heim C, et al. (2017). The COMPASS initiative: description of a nationwide collaborative approach to the care of patients with depression and/or cardiovascular disease. General Hospital Psychiatry, 44, 69–76.

de Groot, M., Golden, S. H., & Wagner, J. (2016, October). Psychological conditions in adults with diabetes. The American Psychologist, 71(7), 552–562.

Devarajooh, C., & Chinna, K. (2017). Depression, distress and self-efficacy: the impact on diabetes self-care practices. PLoS One, 12(3), e0175096.

Dismuke, C. E., & Egede, L. E. (2011). Association of serious psychological distress with health services expenditures and utilization in a national sample of US adults. General Hospital Psychiatry, 33(4), 311–317.

Dismuke, C. E., Hernandez-Tejada, M. A., & Egede, L. E. (2014). Relationship of serious psychological distress to quality of life in adults with diabetes. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine, 48(2), 135–146.

Egede, L. E. (2005). Effect of depression on self-management behaviors and health outcomes in adults with type 2 diabetes. Current Diabetes Reviews, 1(3), 235–243.

Egede, L. E. (2006). Disease-focused or integrated treatment: diabetes and depression. The Medical Clinics of North America, 90(4), 627–646.

Egede, L. E. (2007). Failure to recognize depression in primary care: issues and challenges. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 22, 701–703.

Egede, L. E., Bishu, K. G., Walker, R. J., & Dismuke, C. E. (2016, May). Impact of diagnosed depression on healthcare costs in adults with and without diabetes: United States, 2004–2011. Journal of Affective Disorders, 195, 119–126.

Egede, L. E., & Bonadonna, R. (2003). Diabetes self-management in African Americans: An exploration of the role of fatalism. The Diabetes Educator, 29(1), 105–115.

Egede, L. E., & Dismuke, C. E. (2012). Serious psychological distress and diabetes: a review of the literature. Current Psychiatry Reports, 14, 15–22.

Egede, L. E., & Ellis, C. (2010a). Development and psychometric properties of the 12-item Diabetes Fatalism Scale. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 25, 61–66.

Egede, L. E., & Ellis, C. (2010b). Diabetes and depression: global perspectives. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice, 87, 302–312.

Egede, L. E., Grubaugh, A. L., & Ellis, C. (2010). The effect of major depression on preventive care and quality of life among adults with diabetes. General Hospital Psychiatry, 32(6), 563–569.

Egede, L. E., & Osborn, C. Y. (2010, March–April). Role of motivation in the relationship between depression, self-care, and glycemic control in adults with type 2 diabetes. The Diabetes Educator, 36(2), 276–283.

Egede, L. E., Walker, R. J., Bishu, K., & Dismuke, C. E. (2016). Trends in costs of depression in adults with diabetes in the United States: Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, 2004–2011. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 31(6), 615–622.

Egede, L. E., Williams, J. S., Voronca, D. C., Gebregziabher, M., & Lynch, C. P. (2017, March). Telephone-delivered behavioral skills intervention for African American adults with type 2 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 23. Epub ahead of print.

Egede, L. E., & Zheng, D. (2003). Independent factors associated with major depressive disorder in a national sample of individuals with diabetes. Diabetes Care, 26(1), 104–111.

Egede, L. E., Zheng, D., & Simpson, K. (2002). Comorbid depression is associated with increased health care use and expenditures in individuals with diabetes. Diabetes Care, 25, 464–470.

Ell, K., Katon, W., Xie, B., Lee, P., Kapetanovic, S., Guterman, J., & Chou, C. (2011). One-year postcollaborative depression care trial outcomes among predominantly Hispanic diabetes safety net patients. General Hospital Psychiatry, 33, 436–442.

Fisher, E. B., Chan, J. C., Nan, H., Sartorius, N., & Oldenburg, B. (2012). Co-occurrence of diabetes and depression: conceptual considerations for an emerging global health challenge. Journal of Affective Disorders, 142(Suppl), S56–S66.

Fisher, L., Glasgow, R. E., & Strycker, L. A. (2010). The relationship between diabetes distress and clinical depression with glycemic control among patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care, 33, 1034–1036.

Fisher, L., Hessler, D., Glasgow, R. E., Arean, P. A., Masharani, U., Naranjo, D., et al. (2013). REDEEM: a pragmatic trial to reduce diabetes distress. Diabetes Care, 36, 2551–2558.

Fisher, L., Hessler, D. M., Polonsky, W. H., & Mullan, J. T. (2012). When is diabetes distress clinically meaningful? Establishing cut points for the Diabetes Distress Scale. Diabetes Care, 35, 259–264.

Fisher, L., Mullan, J. T., Arean, P., Glasgow, R. E., Hessler, D., & Masharani, U. (2010). Diabetes distress but not clinical depression or depressive symptoms is associated with glycemic control in both cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses. Diabetes Care, 33, 23–28.

Frandsen, B. R., Joynt, K. E., Rebitzer, J. B., & Jha, A. K. (2015). Care fragmentation, quality and costs among chronically ill patients. The American Journal of Managed Care, 21(5), 355–362.

Gao, J., Wang, J., Zheng, P., Haardofer, R., Kegler, C., Zhu, Y., et al. (2013). Effects of self-care, self-efficacy, social support on glycemic control in adults with type 2 diabetes. BMC Family Practice, 14, 66.

Gilbody, S., Sheldon, T., & House, A. (2008). Screening and case-finding instruments for depression: a meta-analysis. CMAJ, 178, 997–1003.

Gilmer, T. P., O’Connor, P. J., Rush, W. A., Crain, A. L., Whitebird, R. R., Hanson, A. M., et al. (2005). Predictors of heath care costs in adults with diabetes. Diabetes Care, 28(1), 59–64.

Golden, S. H., Lazo, M., Carnethon, M., Bertoni, A. G., Schreiner, P. J., Diez Roux, A. V., … Lyketsos, C. (2008, June 18). Examining a bidirectional association between depressive symptoms and diabetes. Journal of the American Medical Association, 299(23), 2751–2759.

Gonzalez, J. S., Fisher, L., & Polonsky, W. H. (2011). Depression in diabetes: have we been missing something important? Diabetes Care, 34, 236–239.

Gonzalez, J. S., Shreck, E., Psaros, C., & Safren, S. A. (2015, May). Distress and type 2 diabetes-treatment adherence: A mediating role for perceived control. Health Psychology, 34(5), 505–513.

Hessler, D., Fisher, L., Glasgow, R. E., Strycker, L. A., Dickinson, L. M., Arean, P. A., & Masharani, U. (2014). Reductions in regimen distress are associated with improved management and glycemic control over time. Diabetes Care, 37(3), 617–624.

Hilliard, M. E., Yi-Frazier, J. P., Hessler, D., Butler, A. M., Anderson, B. J., & Jaser, S. (2016). Stress and A1c among people with diabetes across the lifespan. Current Diabetes Reports, 16(8), 67.

Holt, R. I., de Groot, M., & Golden, S. H. (2014a, June). Diabetes and depression. Current Diabetes Reports, 14(6), 491.

Holt, R. I., de Groot, M., Lucki, I., Hunter, C. M., Sartorius, N., & Golden, S. H. (2014b, August). NIDDK international conference report on diabetes and depression: current understanding and future directions. Diabetes Care, 37(8), 2067–2077.

Huang, C. Y., Lai, H. L., Lu, Y. C., Chen, W. K., Chi, S. C., Lu, C. Y., & Chen, C. I. (2016, January). Risk Factors and Coping Style Affect Health Outcomes in Adults With Type 2 Diabetes. Biological Research for Nursing, 18(1), 82–89.

Hussey, P. S., Schneider, E. C., Rudin, R. S., Fox, S., Lai, J., & Pollack, C. E. (2014). Continuity and the costs of care for chronic disease. JAMA Internal Medicine, 174(5), 742–748.

Iturralde, E., Weissberg-Benchell, J., & Hood, K. K. (2017, March). Avoidant coping and diabetes-related distress: Pathways to adolescents’ Type 1 diabetes outcomes. Health Psychology, 36(3), 236–244.

Jortberg, B. T., Miller, B. F., Gabbay, R. A., Sparling, K., & Dickinson, W. P. (2012). Patient-centered medical home: how it affects psychosocial outcomes for diabetes. Current Diabetes Reports, 12, 721–728.

Katon, W. J., Von Korff, M., Lin, E. H. B., Simon, G., Ludman, E., Russo, J., et al. (2004). The Pathways Study: a randomized trial of collaborative care in patients with diabetes and depression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 61, 1042–1049.

Kelly, S. J., & Ismail, M. (2015). Stress and type 2 diabetes: a review of how stress contributes to the development of type 2 diabetes. Annual Review of Public Health, 36, 441–462.

Liu, C. W., Einstadter, D., & Cebul, R. D. (2010). Care fragmentation and emergency department use among complex patients with diabetes. American Journal of Managed Care, 16(6), 413–420.

Luyckx, K., Seiffge-Krenke, I., & Hampson, S. E. (2010, July). Glycemic control, coping, and internalizing and externalizing symptoms in adolescents with type 1 diabetes: a cross-lagged longitudinal approach. Diabetes Care, 33(7), 1424–1429.

McKnight-Eily, L. R., Elam-Evans, L. D., Strine, T. W., Matthew, M. Z., Perry, G. S., Presley-Cantrell, L., et al. (2009). Activity limitation, chronic disease, and comorbid serious psychological distress in U.S. adults – BRFSS 2007. International Journal of Public Health, 54, S111–S119.

Osborn, C. Y., Bains, S. S., & Egede, L. E. (2010, November). Health literacy, diabetes self-care, and glycemic control in adults with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Technology & Therapeutics, 12(11), 913–919.

Petrak, F., Baumeister, H., Skinner, T. C., Brow, A., & Holt, R. I. (2015). Depression and diabetes: treatment and health-care delivery. The Lancet Diabetes and Endocrinology, 3, 472–485.

Piette, J. D., Resnicow, K., Choi, H., & Heisler, M. (2013). A diabetes peer support intervention that improved glycemic control: mediators and moderators of intervention effectiveness. Chronic Illness, 9(4), 258–267.

Piette, J. D., Richardson, C., & Valenstein, M. (2004, February). Addressing the needs of patients with multiple chronic illnesses: the case of diabetes and depression. The American Journal of Managed Care, 10(2 Pt 2), 152–162.

Puyat, J. H., Kazanjian, A., Wong, H., & Goldner, E. (2017). Comorbid chronic general health conditions and depression care: a population-based analysis. Psychiatric Services. Epub ahead of print.

Rush, A. J., Giles, D. E., Schlesser, M. A., Fulton, C. L., Weissenburger, J., & Burns, C. (1986). The inventory for depressive symptomatology (IDS): preliminary findings. Psychiatry Research, 18(1), 65–87.

Schoenberg, N. E., Drew, E. M., Stoller, E. P., & Kart, C. S. (2005). Situating stress: lessons from lay discourses on diabetes. Medical Anthropology Quarterly, 19(2), 171–193.

Schoenfelder, T. (2012). Patient satisfaction: a valid indicator for the quality of primary care. Primary Health Care, 2, 4.

Shin, J. K., Chiu, Y. L., Choi, S., Cho, S., & Bang, H. (2012). Serious psychological distress, health risk behaviors, and diabetes care among adults with type 2 diabetes: the California Health Interview Survey 2007. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice, 95(3), 406–414.

Simon, G. E., Katon, W. J., Ludman, E., VonKorff, M., Ciechanowski, P., & Young, B. A. (2005). Diabetes complications and depression as predictors of health service costs. General Hospital Psychiatry, 27(5), 344–351.

Sousa, V. D., Zauszniewski, J. A., Musil, C. M., Lea, P. J. P., & Davis, S. A. (2005). Relationships among self-care agency, self-efficacy, self-care, and glycemic control. Research and Theory for Nursing Practice, 19(3), 217–230.

Stoop, C. H., Nefs, G., Pommer, A. M., Pop, V. J. M., & Pouwer, F. (2015). Effectiveness of a stepped care intervention for anxiety and depression in people with diabetes, asthma, or COPD in primary care: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Affective Disorders, 184, 269–276.

Stopford, R., Winkley, K., & Ismail, K. (2013). Social support and glycemic control in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review of observational studies. Patient Education and Counseling, 93, 549–558.

Strom, J. L., & Egede, L. E. (2012). The impact of social support on outcomes in adult patients with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review. Current Diabetes Reports, 12, 769–781.

Surwit, R. S., Schneider, M. S., & Feinglos, M. N. (1992). Stress and diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care, 15(10), 141–1422.

Thoits, P. A. (1985). Social support and psychological well-being: theoretical possibilities. In I. G. Sarason & B. R. Sarason (Eds.), Social support: Theory, research, and application (pp. 52–72). Mass: Kluwer/Hingram.

Unutzer, J., & Ratzliff, A. H. (2015). Evidence base and core principles. In L. E. Raney (Ed.), Integrated care: Working at the interface of primary care and behavioral health. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association.

van Dam, H. A., van der Horst, F. G., Knoops, L., Ryckman, R. M., Crebolder, H. F. J. M., & van den Borne, B. H. W. (2004). Social support in diabetes: a systematic review of controlled intervention studies. Patient Education and Counseling, 59, 1–12.

Walker, R. J., Gebregziabher, M., Martin-Harris, B., & Egede, L. E. (2014). Relationship between social determinants of health and processes and outcomes in adults with type 2 diabetes: validation of a conceptual model. BMC Endocrine Disorders, 14, 82.

Walker, R. J., Gebregziabher, M., Martin-Harris, B., & Egede, L. E. (2015). Quantifying direct effects of social determinants of health on glycemic control in adults with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Technology & Therapeutics, 17(2), 80–87.

Walker, R. J., Smalls, B. L., Hernandez-Tejada, M. A., Campbell, J. A., Davis, K., & Egede, L. E. (2012). Effect of diabetes fatalism on medication adherence and self-care behaviors in adults with diabetes. General Hospital Psychiatry, 34(6), 598–603.

Weissman, J. F., Pratt, L. A., Miller, E. A., & Parker, J. D. (2015). Serious psychological distress among adults: United States, 2009–2013. NCHS Data Brief, 203, 1–8.

Williams, S. A., Pollack, M. F., & Dibonaventura, M. (2011). Effects of hypoglycemia on health-related quality of life, treatment satisfaction and healthcare resource utilization in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice, 91(3), 363–370.

Winchester, R. J., Williams, J. S., Wolfman, T. E., & Egede, L. E. (2016). Depressive symptoms, serious psychological distress, diabetes distress and cardiovascular risk factor control in patients with type 2 diabetes. Journal of Diabetes and its Complications, 30, 312–317.

Young-Hyman, D., de Groot, M., Hill-Briggs, F., Gonzalez, J. S., Hood, K., & Peyrot, M. (2016, December). Psychosocial care for people with diabetes: A position statement of the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care, 39(12), 2126–2140.

Zilioli, S., Ellis, D. A., Carré, J. M., & Slatcher, R. B. (2017, April). Biopsychosocial pathways linking subjective socioeconomic disadvantage to glycemic control in youths with type I diabetes. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 78, 222–228.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 Springer International Publishing AG, part of Springer Nature

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Walker, R.J., Williams, J.S., Egede, L.E. (2018). Behavioral Health and Diabetes. In: Duckworth, M., O'Donohue, W. (eds) Behavioral Medicine and Integrated Care. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-93003-9_17

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-93003-9_17

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-93002-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-93003-9

eBook Packages: Behavioral Science and PsychologyBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)