Abstract

In 2016, a group of collaborators from South Africa, Germany, and the United States met to plan and execute an adaptation of the “Secret History” training method from the South African to the German context. The training focuses on building empathic and self-care skills with health care workers. The project was unique in that it is an example of a transfer of a training program from the Global South to the Global North. Regardless of the direction of transfer, the challenges of cultural adaptation remain. Consequently, this chapter includes a brief explanation of the “Secret History” training method, gives an overview of existing approaches for cultural adaptation of interventions, describes the steps involved in our adaptation process, and summarizes our results with a view to improving local acceptability and uptake.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

4.1 Introduction

Global institutional collaborations are typically focused on research, education, or training. These collaborations provide opportunities for the exchange of information and academic practices across countries and hemispheres. However, in addition to academic purposes, one of the ultimate goals of collaboration should be that local communities benefit from their involvement.

These motivating factors came together in 2016 when the “Secret History” adaptation project was funded by the Pan Institution Network for Global Health (PINGH). The primary aim of the project was to culturally adapt and test a novel training – the “Secret History” method – that supports empathy and self-care skills for health workers.

This chapter describes the project, but also illustrates how this project benefitted from a true global collaboration. The project team included researchers from University of Cape Town, South Africa , where the method was developed; Pennsylvania State University, USA; and the target institution, University of Freiburg Medical Center, Germany . The team brought together extensive knowledge of the intervention, implementation, evaluation, clinical expertise, access to the relevant participants, and international project management.

Being part of PINGH allows for efficient replication in other PINGH member institutions, and institutions beyond PINGH. In this way, the project broadens PINGH’s scope of interventions, training, and improvement of clinical care. The experiences and lessons learned from this project not only contribute to the body of scientific knowledge, but allow for reflection and response to the strengths and opportunities of global collaborations.

4.2 “Secret History”

The original setting and rationale

Staff working in obstetric services in South Africa are confronted with high levels of obstetric morbidity and mortality, and frequently experience compassion fatigue and burnout (Mashego et al. 2016). Linked to this, there have been several reports over the years of abusive care by healthcare staff of their pregnant clients, especially in the labour ward setting (Jewkes et al. 1998; Kruger and Schoombee 2010; Rothmann et al. 2006; Odhiambo 2011).

At the same time, in South Africa , the diagnostic prevalence of depression during pregnancy and in the first postpartum year, ranges from 22% to 47% and is closely associated with social adversity including food insecurity and domestic and community violence (Rochat et al. 2011; van Heyningen et al. 2016). These rates compare with the 11–12% range typically cited for high income countries (Woody et al. 2017).

The Perinatal Mental Health Project (PMHP) , at the University of Cape Town, argues that a critical foundational element to mental health service development for mothers is to address, as an initial step, the distress and abuse so typical in the obstetric environment. In order to do this, the “Secret History” training method was developed in 2004.

The training

This 2 to 4 h interactive training session uses group role-play to enable care providers to re-enact a typical disrespectful scenario, and thereafter an empathic engagement between provider and mother (patient). Scenarios are designed to reveal the social and emotional vulnerabilities of both characters. Participants adopt the role of care provider or patient, and with the help of facilitators, elements of the characters’ histories are revealed in stages to encourage spontaneous interaction. The roles are reversed for each scenario so that each participant can experience the perspective of “the other.” During the simulation of both the disrespectful and empathic cases, the facilitators interrupt the “play” and ask how the characters are feeling and what they need. A didactic component on empathic engagement skills is interposed between the two cases and a debriefing session occurs after each of the cases is enacted. A discussion on self-care is incorporated into each of the debriefing sessions .

The target setting and rationale

Major problems in South Africa n (SA) public health settings such as lack of supplies, unsafe working environments and limited support and supervision (Breier et al. 2009; Coovadia et al. 2009), as well as social issues of SA nurses such as economic vulnerability and prevalent domestic violence (Oosthuizen and Ehlers 2007; Sprague et al. 2016), by and large do not apply to German nurses and midwives and their working conditions. However, there are a number of other factors supporting the relevance of the “Secret History” method for the medical field in High Income Countries (HICs).

First, the relevance of empathic care for optimal health outcomes is well known globally. Apart from state-of-the art pharmaceutical and technical treatment, the relationship between the health care provider and the patient is a very powerful tool to ensure patient adherence and satisfaction, both of which are desirable health outcomes (Fuertes et al. 2007; Hillen et al. 2011). In the perinatal period especially, interpersonal quality of care is relevant for prevention (e.g. Ashby et al. 2016; Olds 2006). Empathic care can exert a positive influence on the emotional experience of the mother during pregnancy (Seefat-van Teeffelen et al. 2011) and birth (Moloney and Gair 2015).

Second, obstetric violence is not restricted to health care institutions in Low and Middle Income Countries (LMICs). As a recent review on the issue shows, “verbal abuse of women by health providers during childbirth was commonly reported across all regions and country income levels” (Bohren et al. 2015). Women reported being blamed by health workers for poor health outcomes and not being involved in the decision-making process, while also reporting physical abuse such as being neglected during labour, non-consented procedures, and being denied pain medication (Forssén 2012). Another study reports ineffective communication of providers with women during childbirth (e.g. dismissal of women’s concerns during labour, no communication of the need for surgery or intervention) making the women passive participants with only an illusion of choice. Again, participants in the study reported that they felt alone and neglected during their deliveries (Redshaw and Hockley 2010).

Third, the aspect of receiving kind, supportive, and respectful care during labour and birth is known to be of high relevance to women in HICs. While they choose to deliver in a health facility that offers technically sound care to ensure positive health outcomes for themselves and their babies, they also expect emotional support (Bohren et al. 2015). They are dissatisfied when staff appear as inconsiderate or uncaring, and when they were excluded from decision-making—their labour being “taken over by strangers or machines” (Small et al. 2002). In HIC hospital settings, obstetric care is typically oriented to organizational protocols, revolving around routines and standard practices rather than around the women’s individual concerns (Coyle et al. 2001). Again, this leads to depersonalized care, lack of rapport between providers and patients, and the perception that health care providers lack empathy (Coyle et al. 2001).

For the German context , no scientific studies on birth experiences in the hospital setting could be found. However, the numerous recent reports (Mundlos 2015) and counselling literature (Sahib 2016; Meissner 2011; Bloemeke 2015) available on the topic show that it is a pressing issue .

When searching for existing trainings in empathy and/or self-care for professionals working in maternal care in a systematic literature review (Hänselmann et al. 2017), 13 final results were retrieved. Of those, only four formats combined empathy and self-care as learning objectives. Moreover, most of the reported training formats were modules in undergraduate or vocational training (12), and only one was designed as further training for practising maternal care staff. Based on these findings, the “Secret History” appears unique. The training is in a flexible and short format. It can be used in vocational and undergraduate contexts, as well as in work-based further training, and brings together the complementary skills of empathy and self-care.

Existing communication training at the University of Freiburg (for medical students), Freiburg Academy of Medical Professions (for midwifery and nursing students), and at the obstetric ward of University of Freiburg Medical Center (work-based further training for practicing nurses and midwives) also takes the form of case-based role-play, involving the participants actively. Usually, role-play is conducted either in small groups of three, where the roles of care provider, patient, and observer are rotated, or in a fish-bowl setting with two participants taking the roles of care provider and patient and the rest of the group functioning as observers. In this setting, desirable communication and empathic behavior is practiced. However, group role-play, as well as the acting out of disrespectful care as an opportunity for further reflection, are not being used. Furthermore, the foci on feelings and needs of the care provider (self-care aspect) and on the contribution of the provider’s own emotional “baggage” to a potential vicious circle of disrespect are usually lacking (Personal communication with: head of midwifing school on May 3rd and June 9th 2016; head of nursing school on May 4th 2016; nursing expert in charge of further training on the obstetric ward on Jan. 19th and June 9th 2016; psychologist in charge of communication training for medical students on Jan. 25th 2016; trainer for communication in further training for medical doctors on Feb. 15th 2016).

Based on the described contextual background of obstetric care in HICs, and the lack of comparable training formats for empathy and self-care in the context of health care education in Freiburg, the adaptation of “Secret History” was initially judged to be desirable and promising by the project team. This judgment was later confirmed by the results of the focus group discussion and pilot test.

4.3 Cultural Adaptation of Interventions

Health and Culture

Culture has been defined as a “socially constructed constellation consisting of such things as practices, competencies, ideas, schemas, symbols, values, norms, institutions, goals, constitutive rules, artefacts, and modifications of the physical environment” (Fiske 2002).

This definition can be applied to national cultures , but it can also be used to describe cultural differences within a society such as those between different social classes or professions. Barrera refers to these “smaller and more homogeneous unit[s] of social organization within a larger ethnic population that [are] bound by shared life experiences” as “subgroups” (Barrera et al. 2013, emphasis added). The staff at a health care organization can be seen as such a subgroup, being bound by shared work experience as well as institutional practices, norms, rules, and environments (cultural dimensions as identified by Fiske 2002) which are different from those in other institutions. Beyond these differences, the constructs of health may not be the same for each cultural subgroup. Winkelman notes, “Concepts of health and disease differ from culture to culture and even from person to person within a culture” (Winkelman 2013).

Consequently, when adapting trainings for health care workers , besides the most obvious adaptation, i.e. language, accounting for cultural differences is also necessary (Bernal et al. 2009). The modification of interventions to fit the needs of a cultural subgroup will be called “cultural adaptation” in this chapter.

Evidence on Cultural Adaptation

The literature search conducted for this chapter showed an alarming research gap with regard to cultural adaptation of trainings for health care staff between countries.

Research has been done on cultural adaptation of prevention interventions for patients, especially with regard to prevention and management of HIV/AIDS (e.g. Dévieux et al. 2004; Wainberg et al. 2007; Wilson and Miller 2003; Wingood and DiClemente 2008) and diabetes (e.g. Barrera et al. 2012; Davis et al. 2011; Hawthorne et al. 2010; Osuna et al. 2011). One publication was found on the cultural adaptation of health services (T-share Team 2012), but this is a practical manual for the development and implementation of new interventions. No studies were identified which deal with evaluating and guiding the cultural adaptation of interventions for health care staff.

Also, most of the available studies have been conducted in the US to adapt prevention interventions for minorities within in the country (Barrera et al. 2012; Davis et al. 2011; Dévieux et al. 2004; Latham et al. 2010; Osuna et al. 2011; Whittemore 2007). Only very few studies discuss cultural adaptations of interventions across countries (Ortega et al. 2012; Kumpfer et al. 2008; Skärstrand et al. 2008; Weichold et al. 2006; Williams et al. 2013; Andree Löfholm et al. 2009); and again, none of these focused on health care workers as a target group. We believe that it would be valuable to generate evidence for this specific group and kind of transfer, prior to planning for larger, more elaborate, multi-centre implementation studies.

In particular, more rigorous scientific studies are needed to validate the process of testing cultural adaptation models and to examine whether the adapted programs really render a better fit to the local needs (Castro et al. 2004). Finally, not only proximal health outcomes, but also measures of reach, adoption by health care providers, engagement and maintenance of effects would be worth evaluating to comprehensively consider intervention impact (Glasgow et al. 1999). As Barrera et al. notes, even if cultural adaptations yield equal health outcomes to the original intervention, they could still show better or worse results with view to participation rates and long-term involvement of participants and stakeholders (Barrera et al. 2013).

However, based on the definition of cultural adaptation and cultural group made above, we found it useful to draw on studies that have conducted intercultural adaptation for a different target population for guidance in the process of adaptation pursued in this pilot project.

Cultural Adaptation of Health Care Interventions

Whenever a training method is adapted, there is the risk of loss of effectiveness. On the other hand, the omission of adaptation has similar risks. The debate on cultural adaptation evolves around the two terms: fidelity – “the delivery of a manualized prevention intervention program as prescribed by the program developer” and adaptation – “the modification of program content to accommodate the needs of a specific consumer group” (Castro et al. 2004).

If comprehensive adaptation is located at one end of a continuum , maximum fidelity would be at the other end. For example, if everything about a training program is changed, it will be a new program altogether, and it cannot reasonably be called a version of the original one and yield comparable results. Maximum fidelity however could only be achieved by having the same trainers deliver the training at the same place, with the same level of experience, training exactly the same content. However, in practice, this rarely occurs as the term fidelity has been conceptualized as sticking with the “driving elements of a program” (Berkel et al. 2011) clearly acknowledging the need for some degree of variation. As Castro et al. note, “The primary aim in cultural adaptation is to generate the culturally equivalent version [italics by EH] of a model prevention program ” (Castro et al. 2004). Therefore, in order to facilitate an equal learning opportunity to a new target group, interventions need to be culturally modified. So instead of “do the same to everyone” the aim becomes “achieve the same learning effect for everyone”.

It has been shown that, “adoption of transported, international programs should not be done without considering adaptation” since culturally adapted versions are more effective than international adopted programs without adaptations (Hasson et al. 2014). Barrera et al. notes that “culturally enhanced interventions” are more effective than “usual care” since cultural fit boost[s] program appeal, appropriateness, and efficacy (Barrera et al. 2013). Lack of cultural fit “would threaten program efficacy, despite high fidelity in program implementation” (Castro et al. 2004). Researchers suggest to develop “hybrid”, “adjustable” interventions which “build in” adaptation to assure cultural relevance and community ownership, while also maximizing fidelity of implementation and program effectiveness (Castro et al. 2004).

But the practical questions of adaptation remain such as what to change, how much, and in what order, to provide that equal learning experience. Fortunately, the risks of compromising program efficacy by too extensive or too little modification can be counteracted by following a well-structured, scientifically robust process of adaptation.

In the last 12 years, stage models of adaptation have emerged which show a considerable degree of congruence (Barrera and Castro 2006; Domenech Rodríguez and Wieling 2005; Kumpfer et al. 2008; McKleroy et al. 2006; Wingood and DiClemente 2008). This, together with the effectiveness of stage-developed cultural adaptations speak in favour of the validity and utility of the staged adaptation models (Barrera et al. 2013).

Combined Stage-Model

Barrera et al. (2013) synthesize the evidence on multiple adaptation models and suggest a five-step model of cultural adaptation which integrates the respective processes suggested by several research studies (Barrera and Castro 2006; Kumpfer et al. 2008; McKleroy et al. 2006; Wingood and DiClemente 2008). This approach was identified as the most practicable and applicable and served as a basis of the adaptation process followed in the “Secret History” pilot project:

-

1.

Information Gathering – here differences of the original and new target groups are sought out by literature research and preliminary investigation with regard to (a) participant characteristics, (b) program delivery staff, (c) administrative/community factors, and (d) needs and intervention preferences of the new target group. Additionally, suggestions for additions and improvement to the original intervention are gathered even in this early stage and the target community’s capacity to implement the intervention is assessed.

-

2.

Preliminary Adaptation Design – here intervention materials and if necessary intervention activities are adapted in cooperation with local stakeholders.

-

3.

Preliminary Adaptation Test – here local staff are trained to deliver the preliminary version of the adaptation and pilot studies are conducted. Evaluation of these sessions should check for (a) implementation difficulties, (b) difficulties with program content or activities/satisfaction with intervention elements, and (c) suggestions for improvement.

-

4.

Adaptation Refinement – here the intervention is revised further based on the precedent step.

-

5.

Cultural Adaptation Trial – this includes a full trial of the revised intervention to check if the desired effects occurred.

4.4 Applying the Adaptation Steps to “Secret History”

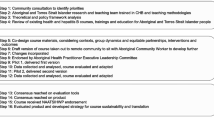

Barrera’s five stage adaptation process was used to guide and inform die adaptation of the “Secret History” method from the South Africa n to German context (Fig. 4.1).

Step 1 Information Gathering

The main activities in this step of adaptation were review of the adaptation literature, as described in the previous section of this chapter. Literature was searched on empathy in perinatal care and strain on obstetric staff in the context of the global north in order to obtain a first impression if the method would be relevant to the target context. Furthermore, contact was made with the relevant stakeholders to find out if they were interested in the method. Stakeholder interest was identified as the main criterion for the target community’s capacity to implement the intervention in the context of a university medical center. Stakeholders included experts in mental health care, obstetrics and gynaecology, nursing, and midwifery (Fig. 4.2).

Conversations were aimed to assess interest in the project, feasibility, and sustainability. Stakeholders were also requested to recruit participants for the subsequent activities. Stakeholders were informed about all the possible and intended steps of the project, it was made clear that there was no obligation to participate, and that they could opt out at any stage.

Step 2 Preliminary Adaptation Design

Activities in this step include a focus group to find out more about the every-day work setting in obstetrics and about existing and needed education in empathy and self-care. This was used to adapt the training materials. Furthermore, pre and post surveys were developed to be tested in the preliminary adaptation test.

Focus Group

Stakeholders invited staff within their institutions to join the focus group . Along with the invitation and study information, a written consent form was emailed to the participants prior to the discussion. There were two aims of the focus group. First, participants were asked if the “Secret History” training could be of use for the Freiburg obstetrics setting. The second aim was to extract examples of difficulties Freiburg obstetric staff were facing professionally so that the training material could be adapted accordingly and would provide motivation to the participants. Aims were driven by the literature which notes that:

-

“sources of non-fit and “mismatch effect,” would threaten program efficacy, despite high fidelity in program implementation. Major sources of mismatch are [differences in]: (a) group characteristics, (b) program delivery staff, and (c) administration/community factors” (Castro et al. 2004)

-

“[programs may] lack fit and relevance by not addressing significant issues [of the new … group]” (Castro et al. 2004)

-

“Community adoption of a program and its local adaptation are enhanced by community ownership or “buy-in” to motivate and sustain local community participation.” (Castro et al. 2004)

The focus group included eight participants, lasted two hours and included an introduction and project explanation, structured discussion, and conclusion. Participants filled out a brief demographic survey and were invited to participate in the upcoming pilot testing. The discussion took place in German and was audiotaped. Original versions of the interview guide and the results are available from the first author.

Adaptation of Materials .

After the focus group was concluded and the data were analysed, emerging themes were used to revise the “Secret History” training materials (Table 4.1). As noted previously, “Secret History” includes two role play exercises and these are based on actual cases, or characteristics of multiple cases, that are common in the local setting .

There was positive feedback from the focus group discussion that it was important to conduct the pilot testing and there was a sense of agency created among local stakeholders through their early and influential involvement in this project.

Survey Development

Finally, evaluation materials were designed to capture the knowledge and attitudes of the participants before and after training as well as the knowledge transfer from the training. Although a few validated tools exist to measure empathy, most are for patients to comment on how empathetic they feel their provider to be. One tool was found for health care providers to self-assess their own empathy; however, the licensing fee for that tool was high and using it would not be sustainable for future studies. Therefore, survey research principles were used to develop the survey, as well as a review of the literature on empathy and self-care. A large item bank was created with the idea that items would be culled after the pilot testing if they exhibited ceiling or floor effects .

Step 3 Preliminary Adaptation Test

Participants were invited via email to join the Train-the-Trainer and Pilot testing of the “Secret History” training five weeks in advance. Invitations were sent to those in a position to be facilitating trainings and practicing or teaching/supervising obstetrics staff; including nurses, physicians, and midwives.

The first aim of the workshop was to train potential trainers for the local pilot sessions. The second aim was to make the method known to local decision makers for further pilot testing and implementation. The third aim was to gather feed-back concerning the quality (or further need) of adaptation of the training. The fourth aim was to test the survey item-bank for further adaptation.

In order to ensure fidelity to the original “Secret History”, the developer (S.H.) was asked to facilitate the pilot testing. Given that she does not speak German, a bilingual translator was made available to ensure that the participants could have all the written materials in German. Although all participants were able to speak English, these measures were important as participants of the focus group discussion unanimously stated they may not be able to engage freely in experiential, self-reflective activities in a foreign language. Further to this, a bilingual investigator from the Freiburg team co-facilitated the pilot training.

The Train-the-Trainer and Pilot testing of the “Secret History” training included 13 participants who were mostly female (one male) with extensive job experience (46% of the attendants had more than 20 years of professional experience). Participants included 6 lecturers, 4 practicing nurses/midwives, and 3 other professionals (psychologists, health managers).

The “Secret History” was conducted over four and a half hours. The program included:

-

filling out the pre-survey

-

introductory ice-breaker

-

first role play exercise (disrespectful case)

-

break with refreshments

-

1-h didactic session

-

second role play exercise (empathic case)

-

post survey

-

open discussion and feedback on the training program.

Step 4 Adaptation Refinement

In order to maximize feedback from the Train-the-Trainer and Pilot testing, field notes were taken and the role-play and discussion were audiotaped to retrieve participants’ comments. Together with the results from the pre and post survey, the feedback yielded the following information which was used to complete the adaptation:

-

Although key steps were taken to address the fact that one of the facilitators only spoke English and no negative feedback was noted, we cannot definitively say that there was no impact on the participants. Translation did slow the process and required resources, but this also allowed for the unexpected advantage of facilitators and participants having the time to reflect more thoughtfully on the feelings and needs component within the method. The struggle with trying to articulate the nuances of these through translation allowed for a richer discussion and excavation of the concepts .

-

Generally, all participants agreed that the method had a good mix of didactic and learning exercises and that it was relevant for their job. However, the didactic nature of the input on empathic skills did not seem to be as engaging for participants, who had already had a deep knowledge of empathic skills. It was suggested that the didactic part of the course be given in a more interactive way, especially when dealing with such advanced groups of participants. In this way, the training should take in to account the different level of prior training in the group targeted in Germany as compared to the original South African version, thereby addressing possible mismatch-effects (Castro et al. 2004).

-

In the survey, 6 participants agreed, 6 were undecided, and 1 disagreed when asked if the cases were typical of the local situation. This disagreement was also voiced in the discussion and the different viewpoints seemed to be connected to the different backgrounds of the participants whereby practitioners in obstetrics tended to agree while trainers and psychologists tended to disagree.

-

With respect to the case scenarios used for role-play, several participants suggested in the discussion as well as in the survey, to gather recent problematic situations from the group’s own experience rather than using pre-prepared cases. Doing so may improve local effectiveness of the training as cases brought forward by participants would be directly relevant to them. This would more likely result in an optimal cultural fit. Participant involvement in adaptation of training content would enhance the sense of ownership and thus the motivation to participate with the new target group for the intervention (Castro et al. 2004).

-

Further suggestions were to give more time for role-play and practice of empathic skills, to conduct the training for interprofessional groups working together in obstetrics (include medical doctors) and to present the method with more detail, so that it could be replicated more easily by participants.

-

As only 6 participants said they felt confident they could train others in the “Secret History” method, the objective of training of local staff to deliver the training has not been fully achieved. It seems that several sessions are needed to provide confidence. One major improvement since the time of the pilot testing is that a video illustrating the “Secret History” method is now available online at https://protect-za.mimecast.com/s/37voBeS36N9afa.

-

Item analyses of the pre and post test surveys allowed for the revision of the survey instrument. Items with high ceiling or floor effects that did not hang with the domain intended for measurement were culled from the survey. In addition, feedback allowed for revision of items that were unclear or those that the participants felt were not covered by the content.

Overall, the preliminary adaptation test was successful as the program activities were considered highly acceptable by participants. The developer of the training (S.H.) who facilitated the intervention, noted that participants engaged actively and in the manner that was very similar to the original experience in South Africa . For the subsequent cultural adaptation trials, the recommended refinements which were feasible within the restricted time frame and resources were put into practice . These were:

-

1.

Changing the input on empathy and self-care from a didactic to an interactive format

-

2.

Using recent problematic situations from the group’s own experience as case narratives rather than using pre-prepared ones.

-

3.

Using a shortened version of the survey to be filled out only after receiving the training .

Step 5 Cultural Adaptation Trials

Upon the conclusion of the revisions that were made based on the feedback from the pilot testing, two more training sessions were conducted: one for 22 staff working towards a degree in psychotherapy, facilitated by two people, and another with 12 nursing staff from the women’s clinic (oncological ward) facilitated by one person. An effort was made to find other participant groups for these trials apart from the obstetric staff at University of Freiburg Medical Center as a larger follow-up study is planned with this population. Since inquiries made to other midwifery schools in the region were unsuccessful, and time was limited, we elected to use the two options available.

In both cases, the further adaptation proved helpful, leading to a strong involvement of the participants by visibly valuing and integrating their competencies and experience. It seemed to the facilitators that by integrating this amount of interactive generation of course content (cases for role play and empathic skills), the intervention did effectively become a “hybrid” intervention (Castro et al. 2004) with built-in adaptation to assure cultural relevance and community ownership. However, besides the high degree of involvement of the participants, which was observable and positive, there was mixed acceptability of the training in the survey feedback.

A half of the nurses from the women’s clinic oncology ward stated that after the training, they were better able to understand their patient’s concerns. When asked if the training would affect how they show or feel emotions to their patients, only three agreed. However, a majority of participants agreed, that the training helped them put themselves in their patients’ shoes.

The psychotherapy group reported positive feedback about the training. Nineteen out of 22 participants stated that the learning objectives were fully met and 21 participants noted they would be able to use what they learned from the training in their job. As the long-term trainer of the group noted, the special benefit of “Secret History” compared to other trainings is that it shows the participants how their own feelings and needs can contribute to communication problems if these are not addressed.

The different results of the two groups could have been related to the variation in the number of facilitators and the experience of the facilitators. The latter group was facilitated by an experienced practitioner and trainer in psychotherapy together with E.H. who had been working with the method for a longer time and had the opportunity to co-facilitate the Train-the-Trainer and Pilot testing together with S.H, the developer of the method. However, the first group was facilitated by a psychologist who had been exposed to “Secret History” only in the once-off Train-the-Trainer and Pilot testing. Our experience thus confirms Castro et al.’s statement on differences in program delivery staff being one of the major sources of mismatch-effects threatening program efficacy (Castro et al. 2004).

Compared to the pilot test, native speakers conducted both of these trainings in German. Overall, the two trainings demonstrated that the content was fully translated and adapted to the German context. More work is needed to understand how local staff can be optimally trained to facilitate “Secret History” in their institutions and future work will be devoted to this.

4.5 Conclusions

The purpose of this chapter was to describe how a health care worker training program, developed in South Africa , was adapted to the German setting. While the adaptation was multi-staged and conducted over the course of a year, the lessons learned were valuable for future projects. Most adaptations focus on translating content from one language to another. “Translation from one language to another is the most obvious form of program adaptation” (Castro et al. 2004). But reaching cultural equivalence by eliminating sources of cognitive and/or affective non-fit, raises a greater challenge (Geisinger 1994; González et al. 1995). Our experiences made it clear that adaptation is a resource intensive, comprehensive process that can be accomplished in a structured manner following a well-established framework. As Castro et al. note, “two basic forms of adaptation involve modifying program content and modifying the form of program delivery” (Castro et al. 2004). Our project accomplished both of those and our interdisciplinary team, from three countries, allowed for this to happen in an effective and comprehensive manner. Our project team is encouraged by the positive feedback during this process and the commitment of the academic medical centre to continue to deliver the training. Ultimately, we hope to see the health care worker community in Freiburg sustain the program and to complete adaptation of the “Secret History” training program in other areas.

Challenges

-

Adapting instruments across cultural settings comes with barriers of language, translation, time, and context.

-

Assessment tools can be prohibitively expensive, particularly in the pilot phases of a project.

Lessons Learned

-

Adaptation, although a resource intensive, comprehensive process, can be accomplished in a structured manner following a well-established framework.

-

Our interdisciplinary team, from three countries, allowed for complex adaptation of a training to happen in an effective and comprehensive manner.

-

Culturally sensitive healthcare worker training has the possibility of improving mental health and empathic care.

References

Andree Löfholm C, Olsson T, Sundell K, Hansson K (2009) Multisystemic therapy with conduct-disordered young people: stability of treatment outcomes two years after intake. Evid Policy 5(4):373–397. https://doi.org/10.1332/174426409X478752

Ashby B, Scott S, Lakatos PP (2016) Infant mental health in prenatal care. Newborn Infant Nurs Rev 16(4):264–268. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.nainr.2016.09.017

Barrera M, Castro FG (2006) A heuristic framework for the cultural adaptation of interventions. Clin Psychol Sci Pract 13(4):311–316. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2850.2006.00043.x

Barrera M, Toobert D, Strycker L, Osuna D (2012) Effects of acculturation on a culturally adapted diabetes intervention for Latinas. Health Psychol 31(1):51–54. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025205

Barrera M, Castro FG, Strycker LA, Toobert DJ (2013) Cultural adaptations of behavioral health interventions: a progress report. J Consult Clin Psychol 81(2):196–205. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027085

Berkel C, Mauricio AM, Schoenfelder E, Sandler IN (2011) Putting the pieces together: an integrated model of program implementation. Prev Sci 12(1):23–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-010-0186-1

Bernal G, Jiménez-Chafey MI, Domenech Rodríguez MM (2009) Cultural adaptation of treatments: a resource for considering culture in evidence-based practice. Prof Psychol Res Pr 40(4):361–368. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016401

Bloemeke VJ (2015) Es war eine schwere Geburt: wie schmerzliche Erfahrungen heilen. Kösel, München

Bohren MA, Vogel JP, Hunter EC et al (2015) The mistreatment of women during childbirth in health facilities globally: a mixed-methods systematic review. PLoS Med 12(6):e1001847; discussion e1001847. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001847

Breier M, Wildschut A, Mgqolozana T (2009) Nursing in a new era: the profession and education of nurses in South Africa. HSRC Press, Cape Town

Castro FG, Barrera M, Martinez CR (2004) The cultural adaptation of prevention interventions: resolving tensions between fidelity and fit. Prev Sci 5(1):41–45

Coovadia H, Jewkes R, Barron P et al (2009) The health and health system of South Africa: historical roots of current public health challenges. Lancet 374(9692):817–834. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(09)60951-x

Coyle KL, Hauck Y, Percival P, Kristjanson LJ (2001) Ongoing relationships with a personal focus: mothers’ perceptions of birth centre versus hospital care. Midwifery 17(3):171–181. https://doi.org/10.1054/midw.2001.0258

Davis RE, Peterson KE, Rothschild SK, Resnicow K (2011) Pushing the envelope for cultural appropriateness: does evidence support cultural tailoring in type 2 diabetes interventions for Mexican American adults? Diabetes Educ 37(2):227–238. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145721710395329

Dévieux JG, Malow RM, Rosenberg R, Dyer JG (2004) Context and common ground: cultural adaptation of an intervention for minority HIV infected individuals. J Cult Divers 11(2):49–57

Domenech Rodríguez MM, Wieling E (2005) Developing culturally appropriate, evidence-based treatments for interventions with ethnic minority populations. In: Rastogi M, Wieling E (eds) Voices of color: first-person accounts of ethnic minority therapists. SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks, pp 313–333

Fiske AP (2002) Using individualism and collectivism to compare cultures—a critique of the validity and measurement of the constructs: comment on Oyserman et al. (2002). Psychol Bull 128(1):78–88

Forssén ASK (2012) Lifelong significance of disempowering experiences in prenatal and maternity care: interviews with elderly Swedish women. Qual Health Res 22(11):1535–1546. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732312449212

Fuertes JN, Mislowack A, Bennett J et al (2007) The physician-patient working alliance. Patient Educ Couns 66(1):29–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2006.09.013

Geisinger KF (1994) Cross-cultural normative assessment: translation and adaptation issues influencing the normative interpretation of assessment instruments. Psychol Assess 6(4):304–312

Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, Boles SM (1999) Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. Am J Public Health 89(9):1322–1327

González VM, Stewart A, Ritter PL, Lorig K (1995) Translation and validation of arthritis outcome measures into Spanish. Arthritis Rheum 38(10):1429–1446

Hänselmann E, Husni-Pascha G, Feuchtinger J et al (2017) Training for empathy and/or self-care for professionals and students in maternal care PROSPERO: CRD42017058552. Available from http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.asp?ID=CRD42017058552

Hasson H, Sundell K, Beelmann A, von Thiele Schwarz U (2014) Novel programs, international adoptions, or contextual adaptations?: meta-analytical results from German and Swedish intervention research. BMC Health Serv Res 14(Suppl 2):O32. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-14-S2-O32

Hawthorne K, Robles Y, Cannings-John R, Edwards AGK (2010) Culturally appropriate health education for Type 2 diabetes in ethnic minority groups: a systematic and narrative review of randomized controlled trials. Diabet Med 27(6):613–623. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-5491.2010.02954.x

Hillen MA, de HHCJM, Smets EMA (2011) Cancer patients’ trust in their physician-a review. Psychooncology 20(3):227–241. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.1745

Jewkes R, Abrahams N, Mvo Z (1998) Why do nurses abuse patients? Reflections from South African obstetric services. Soc Sci Med 47(11):1781–1795

Kruger L-M, Schoombee C (2010) The other side of caring: abuse in a South African maternity ward. J Reprod Infant Psychol 28(1):84–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/02646830903294979

Kumpfer KL, Pinyuchon M, Teixeira de Melo A, Whiteside HO (2008) Cultural adaptation process for international dissemination of the strengthening families program. Eval Health Prof 31(2):226–239. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163278708315926

Latham TP, Sales JM, Boyce LS et al (2010) Application of ADAPT-ITT: adapting an evidence-based HIV prevention intervention for incarcerated African American adolescent females. Health Promot Pract 11(3 Suppl):53S–60S. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839910361433

Mashego T-AB, Nesengani DS, Ntuli T, Wyatt G (2016) Burnout, compassion fatigue and compassion satisfaction among nurses in the context of maternal and perinatal deaths. J Psychol Afr 26(5):469–472. https://doi.org/10.1080/14330237.2016.1219566

McKleroy VS, Galbraith JS, Cummings B et al (2006) Adapting evidence-based behavioral interventions for new settings and target populations. AIDS Educ Prev 18(4 Suppl A):59–73. https://doi.org/10.1521/aeap.2006.18.supp.59

Meissner BR (2011) Emotionale Narben aus Schwangerschaft und Geburt auflösen: Mutter-Kind-Bindungen heilen oder unterstützen – in jedem Alter ; [mit Babyheilbad & Heilgespräch], 1st edn. Meissner, Winterthur

Moloney S, Gair S (2015) Empathy and spiritual care in midwifery practice: contributing to women’s enhanced birth experiences. Women Birth 28(4):323–328. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2015.04.009

Mundlos C (2015) Gewalt unter der Geburt: Der alltägliche Skandal, 1st edn. Tectum Wissenschaftsverlag, s.l.

Odhiambo A (2011) “Stop making excuses”: accountability for maternal health care in South Africa. Human Rights Watch, New York

Olds DL (2006) The nurse-family partnership: an evidence-based preventive intervention. Infant Ment Health J 27(1):5–25. https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.20077

Oosthuizen M, Ehlers VJ (2007) Factors that may influence south African nurses’ decisions to emigrate. Health SA Gesondheid 12(2). https://doi.org/10.4102/hsag.v12i2.246

Ortega E, Giannotta F, Latina D, Ciairano S (2012) Cultural adaptation of the strengthening families program 10–14 to Italian Families. Child & Youth Care Forum 41(2):197–212. Springer, US. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-011-9170-6

Osuna D, Barrera M, Strycker LA et al (2011) Methods for the cultural adaptation of a diabetes lifestyle intervention for Latinas: an illustrative project. Health Promot Pract 12(3):341–348. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839909343279

Redshaw M, Hockley C (2010) Institutional processes and individual responses: women's experiences of care in relation to cesarean birth. Birth 37(2):150–159. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-536X.2010.00395.x

Rochat TJ, Tomlinson M, Bärnighausen T et al (2011) The prevalence and clinical presentation of antenatal depression in rural South Africa. J Affect Disord 135(1–3):362–373. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2011.08.011

Rothmann S, van der Colff JJ, Rothmann JC (2006) Occupational stress of nurses in South Africa. Curationis 29(2):22–33

Sahib T (2016) Es ist vorbei – ich weiß es nur noch nicht: Bewältigung traumatischer Geburtserfahrungen. Books on Demand, Norderstedt

Seefat-van Teeffelen A, Nieuwenhuijze M, Korstjens I (2011) Women want proactive psychosocial support from midwives during transition to motherhood: a qualitative study. Midwifery 27(1):e122–e127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2009.09.006

Skärstrand E, Larsson J, Andréasson S (2008) Cultural adaptation of the strengthening families programme to a Swedish setting. Health Educ J 108(4):287–300. https://doi.org/10.1108/09654280810884179

Small R, Yelland J, Lumley J et al (2002) Immigrant women's views about care during labor and birth: an Australian study of Vietnamese, Turkish, and Filipino women. Birth 29(4):266–277. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1523-536X.2002.00201.x

Sprague C, Woollett N, Parpart J et al (2016) When nurses are also patients: intimate partner violence and the health system as an enabler of women’s health and agency in Johannesburg. Glob Public Health 11(1–2):169–183. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2015.1027248

T-share Team (ed) (2012) Transcultural skills for health and care: standards and guidelines for practice and training. ARACNE, Napoli http://tshare.eu/drupal/sites/default/files/confidencial/WP11_co/MIOLO_TSHARE_216paginas.pdf. Accessed 25 Oct 2017. ISBN 978-88-907245-0-3

van Heyningen T, Myer L, Onah M (2016) Antenatal depression and adversity in urban South Africa. J Affect Disord 203:121–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.05.052

Wainberg ML, McKinnon K, Mattos PE et al (2007) A model for adapting evidence-based behavioral interventions to a new culture: HIV prevention for psychiatric patients in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. AIDS Behav 11(6):872–883. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-006-9181-8

Weichold K, Giannotta F, Silbereisen RK et al (2006) Cross-cultural evaluation of a life-skills programme to combat adolescent substance misuse. Sucht 52(4):268–278

Whittemore R (2007) Culturally competent interventions for Hispanic adults with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review. J Transcult Nurs 18(2):157–166. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043659606298615

Williams AB, Wang H, Burgess J et al (2013) Cultural adaptation of an evidence-based nursing intervention to improve medication adherence among people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) in China. Int J Nurs Stud 50(4):487–494. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.08.018

Wilson BDM, Miller RL (2003) Examining strategies for culturally grounded HIV prevention: a review. AIDS Educ Prev 15(2):184–202

Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ (2008) The ADAPT-ITT model: a novel method of adapting evidence-based HIV interventions. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 47(Suppl 1):S40–S46. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181605df1

Winkelman M (2013) Culture and health: applying medical anthropology. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco

Woody CA, Ferrari AJ, Siskind DJ et al (2017) A systematic review and meta-regression of the prevalence and incidence of perinatal depression. J Affect Disord 219:86–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.05.003

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

<SimplePara><Emphasis Type="Bold">Open Access</Emphasis> This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.</SimplePara> <SimplePara>The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.</SimplePara>

Copyright information

© 2018 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Hänselmann, E., Knapp, C., Wirsching, M., Honikman, S. (2018). Intercultural Adaptation of the “Secret History” Training: From South Africa to Germany. In: Winchester, M., Knapp, C., BeLue, R. (eds) Global Health Collaboration. SpringerBriefs in Public Health. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-77685-9_4

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-77685-9_4

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-77684-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-77685-9

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)