Abstract

The aim of this chapter is to report perceived safety levels and geography of fear declared by visitors of a shopping centre in the Swedish capital, Stockholm. Drawing from fieldwork inspections and a small sample survey (N = 253), the study assesses how respondents declare their perceived safety in relation to different shopping environments. Geographical Information Systems (GIS) and statistical techniques underpin the analysis. Findings show that visitors’ profile affects their declared perceived safety. Places that people fear the most are not always the same as the ones where most incidents happen. Although shoplifting was the most common type of crime witnessed by shopping visitors, followed by fights; serious robberies at stores were often pointed out as a source of fear. Strengthening formal and informal surveillance is the preferred suggestion provided by visitors to improve shopping centre safety conditions.

In the shopping mall … young people may want a central place to gather, while the old want freedom from noise, jostling and fear, one shop may wish to sell fast food, while its neighbours may not wish to be buried beneath boxes of half-eaten chicken legs.

(Ekblom, 1995, p. 45)

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

Shopping centresFootnote 1’ size and design vary enormously regardless of where they are in the world, from small regional malls made up of a cluster of ordinary retail stores to megamalls offering a combination of shopping and recreation. However, despite the differences in size, type and security operations (Bamfield, 2012; Lindblom & Kajalo, 2011) researchers often homogeneously define them as ‘enclosed spaces characterized by comprehensive surveillance and security’ (Salcedo, 2003, p. 1084). Shopping centres have additional requirements other than surveillance and security. They need to maximise use and income from floor space at the same time that they must offer an environment that is pleasant and attractive. Therefore, it is important to promote good design to achieve both security and other goals.

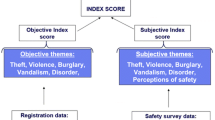

If visitors perceive the shopping centre as unsafe, they may avoid going there. What could cause a shopping centre to be perceived as unsafe? Little research has been devoted to the influence of the physical and social environments on the perceived safety of shopping visitors (but see e.g. Poyser, 2004). Chapter 8 in this book reports on the nature of crime and disorder in space and time in one of the largest shopping centres in the Swedish capital, Stockholm . Using this same shopping centre, this chapter takes a step forward by assessing visitors’ declared perceived safety using a questionnaire (N = 253) and drawing from a conceptual model proposed by Ceccato (2016). This study builds on the work conducted by Kajalo and Lindblom (2016) who previously showed how CPTED—Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design —can be applied to studying consumer attitudes towards different surveillance practices in shopping malls in Finland.

The aim of this study is twofold. Firstly, it is to assess the declared perceived safety of visitors in relation to their personal characteristics as well as to the environment of the shopping mall. Based on this assessment, the study proposes changes to improve shopping centres’ safety conditions. In order to achieve this aim, the study will:

-

1.

Investigate whether perceived safety varies by the characteristics of shopping centre visitors (e.g., gender, age, place of residence, previous victimisation).

-

2.

Assess how respondents declare their perceived safety in different shopping environments.

-

3.

Check for behaviour avoidance in space and time in the shopping centre.

-

4.

Compare the characteristics of crime locations from official statistics and those pointed out by shopping centre visitors responding to the survey .

-

5.

Identify visitors’ sets of preferences in terms of improvements of the shopping centres’ safety conditions.

This chapter is organised as follows. The next section provides the theoretical background for the analysis, including the hypotheses of study. This is followed by the presentation of the study area and then the description of data and methods. Later, results are presented followed by discussion of results, and finally conclusions.

Theoretical Background

Perceived Safety in Shopping Centres

The perception of safety of a shopping mall is fundamental for businesses. If a shopper feels that a shopping centre is not safe (or at least parts of it), then she or he will avoid it and look for another where this basic need–safety–is satisfied. In general, shopping malls tend to be perceived as safer than town centres (Beck & Willis, 1995; Savard & Kennedy, 2014), mainly because they are composed of hermetic buildings with contained and fragmented functions, such as stores, restaurants , entertainment, parking lots.

Visitors’ perceptions of a shopping centre’s safety is a function of a number of overlapping factors such as the characteristics of the customers themselves, the safety conditions of the facility, the quality and maintenance of the shopping mall environment and surrounding areas, and the security system in place (Poyser, 2004; Sandberg, 2016; Savard & Kennedy, 2014). The international literature is populated by examples showing how individual factors affect declared perceived safety; the most common of which include age, gender, place of residence, frequency of use of the place, and previous crime victimisation (Ceccato, 2014; Hale, 1996; Pain, 2000; Skogan & Maxfield, 1981). People who have already been a victim of crime are often more fearful than those who have never being victimised (Hale, 1996); women are more fearful than men (Pain, 2000); older adults express more fear than younger individuals (Lagrange & Ferraro, 1989); familiarity with the environment makes people feel safer (Jackson, Harris, & Valentine, 2017; Valentine, 1990); newcomers (or incomers) may make people fearful (Sandercock, 2000, 2005); and people may declare fear for their family and friends, what is often called ‘altruistic fear’ (Trickett, 2009). In addition, perceived safety can be influenced by other, more multi-scale factors (national, global) that affect individuals in their daily lives through, for instance, the media (Gray, Jackson, & Farrall, 2008; Pain, 2009).

The knowledge (or perception) that a particular place is criminogenic also affects individuals’ perceived safety. Savard and Kennedy (2014) review a number of studies in shopping centres and conclude that reported crime victimisation in shopping centres was much less than visitors’ fear of crime. Yet, shopping centres are perceived as risky facilities (Eck, Clarke, & Guerette, 2007; Eck & Weisburd, 1995), since they may attract thousands of daily shoppers bringing large amounts of cash and credit cards, and then leaving with valuable products, which makes them a crime attractor for offenders (Brantingham & Brantingham, 1995; Eck & Weisburd, 1995). In other words, the types of activities shopping centres provide are bound to create particular conditions for crime at certain places and at particular times. In a shopping centre, shoppers start expressing evidence of functional fear (Jackson & Gray, 2010) by trying to prevent ‘something bad from happening’ so they take precautions that make them feel safer. In this case, shoppers adopt behaviour avoidance (Riger, Gordon, & LeBailly, 1982; Skogan & Maxfield, 1981), either by avoiding going to certain places in the shopping mall and/or at certain times of the day.

Moreover, shopping centres are not isolated from the urban system. Thus, location and reputation of a shopping mall are important factors for all visitors (Kajalo & Lindblom, 2016), as shopping facilities can bring about a large number of crime incidents because of their context. For example, shopping malls are linked to transportation hubs, which are important for the development of people’s routine activity (Cohen & Felson, 1979). According to Felson (1987), shopping centres are connected to larger socio-circulatory systems via major thoroughfares which provide them with convenient access and egress, facilitating crime. Also, shopping facilities in high crime neighbourhoods face extra challenges in terms of crime prevention and ensuring safety since they may tend to absorb crime from and/or irradiate crime to the immediate surroundings (Bowers, 2014).

Shopping Centre Environment and Perceived Safety

The design and maintenance of a facility can impact people’s safety. In shopping centres, Scott (1989) stresses the importance of maintaining visual corridors within buildings in affecting users’ feelings of safety, their actual safety, and in deterring criminals. However, a shopping centre is more than corridors. Poyser (2004) reports on research undertaken to assess whether architects were aware of the link between environmental design and crime when they built shopping centres in the 1960s up to 1990s (the study is a comparison of two English shopping centres). Poyser (2004) found that some architects were more aware than others of the links between the built environment and fear of crime in shopping centres. Moreover, he found that ongoing maintenance and cleanliness of the built environment were signs of control that reassured users. Poyser (2004) concluded that aspects that made visitors feel safe were: open-plan design, good radio communication and presence of CCTV cameras, the layout and design of: transition areas (walkways, lifts), public spaces (squares), entrances (signage at entrances) and immediate surroundings (car parks) (Table 9.1). Image and maintenance inform how the aesthetical atmosphere of the environment can enhance the perceived safety of the area and keep potential criminals away because well-kept environments convey that people are in control of the area. Conversely, a lack of maintenance can encourage crime (because the environment provides clues that formal surveillance is not present) and also negatively affect visitors’ perceived safety.

Research has indicated other factors that also impact safety in a shopping mall, including the amount of people present, illumination and surveillance (Savard & Kennedy, 2014). Surveillance , for example, the most known CPTED principle, can be implemented in many ways. In a shopping centre, formal surveillance is often carried out by security guards and shopkeepers, whereas informal surveillance is performed by customers , visitors and/or transients of a place (Hilborn, 2009). Natural surveillance can also be facilitated by creating the sense of territoriality , referring to how physical design can develop a sense of ownership in specific areas (Reynald, 2014), for example places clearly identified between stores and public places. Designing spaces with a specific purpose can also help regulate access, and target hardening measures can make it difficult for people to steal or damage private and/or public property (e.g., alarms at store entrances, CCTV cameras).

Although shopping malls vary greatly in terms of security programs Savard & Kennedy (2014) and Koskela (2000, p. 245) corroborated the importance of surveillance by stating that surveillance and the practices that emanate from it are aimed not only at protecting property and reducing violence but also at creating a perception of safety. More recently, Kajalo and Lindblom (2016) applied CPTED to investigate how consumers view various formal and informal surveillance practices in the context of shopping malls. They found that consumers have different preferences for, for instance, clean and well-lit premises, parking lots, sales personnel, and target-hardening security . They also showed that shoppers differ in many ways in terms of patronage behaviour, some emphasising the importance of overall safety in relation to other factors, such as location, variety of stores, illumination, maintenance, reputation. Interestingly, the authors also found that good location and good reputation of the shopping centre are equally important to all consumer groups. The results of the study indicate that CPTED is useful as an inventory tool, as the empirical results reflect the distinction between informal and formal surveillance .

Using previous literature on retail crime, situational crime prevention theory (Clarke, 1989) and principles from CPTED (Armitage, 2013; Cozens, Saville, & Hillier, 2005; Ekblom, 1995, 2013), Ceccato (2016) suggested a conceptual model for the analysis of shopping premises. The conceptual model splits the shopping centre into five parts classified according to their relevance in relation to their situational conditions of crime and perceived safety. For example, functional spaces are those spaces which have a defined function in the shopping mall, such as stores, restaurants , banks or toilets. The entrances/exits are the second type of criminogenic environment and can be of many types, for example, for pedestrians, cars, for parking lot access. Shopping centres also have transitional areas, such as corridors, stairs and paths. Public spaces are settings of convergence most of the time, such as food courts, but toilets also compose examples of these places. The shopping centre’s immediate surroundings are also an important criminogenic factor influencing what happens inside the mall, as discussed further in Chap. 8.

Hypotheses of Study

Following the evidence from previous research on crime and perceived safety, the following hypotheses are tested in this study:

-

1.

Visitors’ profile (individual characteristics) influences their declared perceived safety in the shopping centre. For instance, those who declare feeling less safe are more likely to be female. Being a previous victim or witness of a crime affects visitors’ declared perceived safety. More frequent visitors will declare feeling safer than will less frequent visitors.

-

2.

Visitors’ perceived safety at a shopping mall is affected by the mall’s environmental attributes in different parts of the facility reflecting the five parts-framework suggested by Ceccato (2016).

-

3.

Places that people fear the most are the ones where the most respondents witness incidents.

-

4.

Due to levels of fear, visitors plan their visits to the shopping centre and avoid particular places and/or times.

-

5.

Visitors have different preferences with regards to improvements of safety conditions in the context of shopping malls.

Study Area

The shopping centre chosen as the study area is one of the Stockholm region’s largest shopping centres with over 180 shops and the longest opening hours, 10 am–9 pm and for bars up to midnight. (This is the same retail establishment as the one analysed in Chap. 8 in this book.) This shopping mall has a large number of restaurants including a food court and leisure activities such as a movie theatre, a bowling alley and go-cart track; as well as a library, student housing and a hotel. The mall is located adjacent to a metro line in the outskirts of Stockholm , in an area with relatively high crime levels (BRÅ, 2016). When built in the late 1970s, the shopping centre was not planned with CPTED principles in mind, and it has been refurbished several times since the 1980s but CPTED principles have never explicitly been incorporated in the shopping centre’s design. As a historical reference, Sweden has about 300 shopping centres, twice as many as the country had ten years ago (Swedish Trade Federation, 2015). The implementation of CPTED guidelines started in the late 1990s in Sweden , but it was not until 2005 that the National Housing Board incorporated some CPTED principles in their policies (Grönlund, 2012); yet even today these principles are not mandatory in new housing developments or commercial buildings.

In 2013, an overwhelming majority (71 per cent) of crimes recorded by the police at the address of the shopping mall consisted of thefts, including pickpocketing, shoplifting , other thefts, fraud , violence (including robbery) and physical damage/vandalism (Fig. 9.1). However, these figures should be analysed with caution since it has been estimated that only 10 per cent of the violence that occurred at the shopping mall’s address is reported to the police (Johansson, 2016).

Police recorded offences in the shopping centre, 2013. N = 1060 corresponds to 71 percent of offences recorded by the police in a single pair of coordinates at the shopping centre (lost and found and other minor types of crimes were excluded). Data Source: Stockholm Police headquarters statistics, 2014.

The official data from the security company show a different pattern. Out of 5768 records of crimes and events of public disorder from January 2014 to May 2015, 68 percent were acts of public disturbance and vandalism. There were also violent acts and/or threats, which composed 16 percent of incidents. Theft, robbery and shoplifting (16 per cent of incidents) were common in jewellery stores, electronic/mobile phone stores, clothing stores as well as supermarkets . For more details, see section ‘Results’.

Data and Methods

We first started with collecting official data from the shopping centre, followed by fieldwork inspection. We then moved to data acquisition through a face-to-face questionnaire and, finally, to analysing the different data sources and comparing and mapping the results.

The Fieldwork Inspection

A systematic and detailed ‘inspection’ of the shopping centre and surrounding areas (including photographic documentation) was performed between June and August 2016. Using CPTED principles, a template had been developed to check the conditions at these locations—illumination, dark corners, hiding places, clear field of view, transparent materials, presence of objects/barriers, levels of maintenance, formal and informal social control, target-hardening features, social environment and the land use of the immediate environment—categorised by type of environment in the shopping centre according to Ceccato (2016).

The Questionnaire

A total of 253 people (visitors of the shopping centre) stratified by gender and age answered a questionnaire utilizing Google forms on a mobile phone. Perceived safety in the shopping centre was measured by different questions asking about: (a) the visitor’s own previous victimization; (b) visitor’s witnessing events of public disturbance in the shopping mall; (c) the safety of their families and friends (victimisation and perceived safety); (d) particular time and places the visitor felt unsafe in and near the mall; (e) the visitor’s overall perceived safety in the shopping mall. The questionnaire was conducted between August 11 and September 7, 2016. When asked about crimes and events of public disturbance, people were asked to describe the places where they occurred and locate them on a map of the mall.

The respondent sample is as follows: 51 per cent female and 49 per cent male; 50 per cent 25 years old and younger and 50 per cent 26 years and older (22 per cent 26–35 years old, 11 per cent 36–45 years old, 10 per cent 46–55 years old, and 7 per cent 56 years old and above). As many as 40 per cent of respondents live in the same district or municipality as the shopping centre, but the majority (60 per cent) come from other places in the Stockholm region. 30 percent of the respondents visit the shopping centre every day, to eat, shop and/or work; a 25 per cent are frequent visitors, coming a few times a week for similar reasons; while 45 per cent visit a few times per month or less. As many as 66 per cent of respondents are native Swedes, 25 per cent were born outside Europe, with the rest born in Scandinavia or in another European country. Note that the sample also reflects the fact that the shopping centre is located in a highly multicultural residential area of Stockholm, with a student housing and a hotel close by.

The Analysis and Mapping

A database containing data from the questionnaire and maps was created as a basis for the analysis. The statistics are analysed using a standard statistical package (in this case IBM SPSS version 23) through descriptive statistics such as frequencies and cross-tables with Chi-square and risk diagnostics. A representation of where shopping visitors witnessed crime and where they felt unsafe on the main floor of the shopping mall was created by using mapping functions in a desktop mapping system (in this case MapInfo Professional version 11).

Results

The Perceived Safety of the Visitors

As many as 85 per cent of questionnaire respondents declare feeling safe in the shopping centre. The large majority are satisfied with supply of stores and restaurants , food court, cinema, library, and parking lots, but are less satisfied with places like toilets and corridors. Despite being satisfied with their own personal safety, respondents declare worry for the safety of their family and friends in the shopping mall (21 per cent declare feeling worried about them). Those who feel unsafe tend to be more anxious during evening hours. However, not all respondents are equally satisfied with perceived safety in the shopping centre. Chi-square analyses and risk estimates show that men are half as likely to declare feeling personally unsafe in the shopping centre compared to women (χ2(1, N = 253) = 4.08, p < 0.05) or feeling worried for their families and friends (χ2(1, N = 253) = 6.45, p < 0.05). Women are more likely than men to point out places where they feel unsafe in the shopping centre (χ2(1, N = 253) = 9.44, p < 0.01), but there are no differences between men and women in avoiding certain times of the day (or places) in the shopping centre. People born outside Sweden are less likely to feel safe in the shopping mall than the native born Swedes (χ2(1, N = 253) = 4.76, p < 0.05). The youngest visitors (25 years old and younger) are less likely to declare feeling unsafe in the shopping centre than all other categories (χ2(2, N = 253) = 3.87, p < 0.05) and less worried about their families’ and friends’ safety in the shopping mall compared to older visitors (χ2(2, N = 253) = 8.61, p < 0.01).

Victimisation and Perceived Safety in the Shopping Centre

Only 5 per cent of respondents declare ever having been a victim of crime, with 1 per cent having been victimised more than once (Fig. 9.2a); often in the afternoon and evening; in functional or public spaces, such as stores, restaurants and the food court; and most commonly victims of pickpocketing, theft, violent conflicts and other types of crimes (Fig. 9.2c). Furthermore, slightly more than a fifth of respondents had already witnessed a crime happening in the shopping mall (Fig. 9.2b). Within the respondent group, shoplifting (theft from stores) is the most common type of crime witnessed, followed by fights, robbery (some heavy robberies in jewellery stores and money exchange stores), thefts and other types of violence and physical damage (Fig. 9.2d). These types of crimes fit well with the incidents recorded by the security company at the mall, but they do not mirror police records, especially because police records more often account for drug-related offences and many economic crimes, such as fraud (Fig. 9.1).

Crime victimisation and witnessing a crime in the shopping centre affects the visitors’ declared perceived safety. Although only 5 per cent have previously been a victim of crime, 21 per cent declared witnessing one in the shopping centre. Moreover, 28 per cent of respondents declare having concerns about their personal safety and/or the safety of family and friends in the shopping centre (of which 59 per cent declare feeling unsafe in the evening). Customers who have previously been victimized in the shopping centre are more likely to declare feeling unsafe in the shopping centre in the evenings compared to those who have not been a victim of crime (χ2(1, N = 253) = 4.79, p < 0.05). Similarly, visitors who have previously witnessed crime in the shopping centre tend to declare themselves less safe compared to those who have never witnessed pickpockets, fights, vandalism or harassment (χ2(1, N = 253) = 9.27, p < 0.00).

Places of Crime and Fear in the Shopping Centre

Different environments in the shopping centre affect individuals’ perceived safety differently. For instance, visitors who have concerns about being victimized in the shopping centre are also dissatisfied with their wellbeing in the following environments: food court (χ2(1, N = 253) = 11.25, p < 0.00), entrances (χ2(1, N = 253) = 2.96, p < 0.05), corridors outside the stores (χ2(1, N = 253) = 8.35, p < 0.00), parking lots (χ2(1, N = 253) = 6.45, p < 0.00) and cinema (χ2(1, N = 253) = 7.81, p < 0.00).

Interestingly, the places that people fear the most are not exactly the same as the places with the most witnessed incidents (Fig. 9.3). Entrances are perceived as the most unsafe (35 per cent). Food court together with toilets and parking lots account for 17 per cent of those unsafe places. The most frequently declared unsafe functional spaces in particular are jewellery stores (39 per cent), electronic stores (31 per cent) but also banks, money exchange, restaurants and places of entertainment, such as the cinema (Fig. 9.3). The immediate surroundings of the shopping mall are also considered unsafe, in particular where the bus terminal is located. Potential reasons for this dissatisfaction with safety conditions in these places are that they are poorly lit, littered, and/or where ‘youth and drunk/drugged people may hang around’.

Further evidence confirms that neighbourhood context has an effect on the perceived safety conditions of the shopping centre. Those who live close by or locally are more worried about safety conditions in the shopping centre than those visitors who live far away (χ2(1, N = 253) = 111.09, p < 0.00). This group of local visitors are particular fearful in the evening hours in the shopping centre (χ2(1, N = 253) = 12.13, p < 0.00). However, familiarity with the shopping mall also affects how people judge safety conditions. Those who go to the shopping centre less frequently are more likely to be worried for their safety in the shopping centre (χ2(1, N = 253) = 45.91, p < 0.00).

Only 4 per cent of the visitors declare that they fear being a victim of crime and that this fear makes them avoid certain places in the shopping centre. The main causes for place avoidance are crowded spots, groups of people moving around in general and in certain areas in the shopping mall, poorly maintained places, poor illumination, knowledge that crimes had occurred at certain stores, witnessing fights. However, 44 per cent of respondents declare avoiding certain times of the evening, especially after 9 pm (or 21).

Perceived Safety by Place Type in the Shopping Centre

The shopping centre was split into five parts classified according to their relevance in relation to their situational conditions of crime and perceived safety (see Ceccato, 2016). Functional spaces are those spaces which have a defined function in the shopping mall, such as stores, restaurants , banks or toilets. Findings indicate that 30 per cent of the places perceived as unsafe in the shopping mall belong to the class functional spaces (note that only 44 respondent (or 17 per cent) indicate unsafe places in the shopping facility). In this shopping centre, they are composed of jewellery, electronic stores but also money exchanges, banks, restaurants and entertainment places (Fig. 9.4).

The entrances/exits are the second type of criminogenic environment as pointed out by Ceccato (2016). They can be of many types; for pedestrians, for cars, for access to the parking lot. In this shopping centre, 34 per cent of places regarded as unsafe are entrances (these entrances are only accessed by foot). It is important to note that when answering this question, some respondents had difficulty in separating the entrances/exits from the shopping mall’s immediate surroundings ; also an important criminogenic factor for what happens inside the mall, especially at this facility that is connected to a regional transportation hub with buses and underground. 11 per cent of places indicated by respondents as unsafe were related to the conditions found in the immediate surroundings, such as rowdy youth, drug-related activities, beggars, drunk people and overall problems of public disturbance.

As many as 17 per cent of the places regarded as unsafe belong to public spaces, and they play a key role in terms of safety as they are settings of convergence of people most of the time. Food court but also toilets are examples of these places. Food court concentrates all sorts of property and violent crimes (see Chap. 8). The inappropriate use of toilets by certain groups of visitors (e.g. washing clothes, smoking, noise) motivated respondents to call for personnel supervisors at toilets. Shopping centres also have transitional areas, such as corridors, stairs, elevators and paths. Length and width, location, types of materials, enclosure and design all affect how safe these transitional areas are perceived to be. In this particular shopping centre, people complained about feeling ‘too crowded’ at particular times of the day. Others highlighted that some of these transitional areas felt desolate and unsafe (Fig. 9.4).

Suggestions for Improving Safety Conditions

Visitors have different preferences with regards to improving safety conditions in the context of shopping malls. When asked how the environment in the shopping mall can be changed to improve safety, the most popular answers were ‘more and visible surveillance’. Figure 9.5 shows all suggestions classified by type into four categories using situational crime prevention theory and CPTED principles as references. A summary of the main safety problems, indicated by the respondents, by type of environment as well as their suggestions for improvements are presented in Table 9.2.

Having toilet staff present at all times was suggested as an improvement in social control (for example, the toilets have been used for washing clothes and smoking) as well as mall hosts, particularly at the entrances. According to the respondents, better surveillance can be achieved by implementing more (and visible) surveillance cameras in public spaces and in stores as well as increased evening presence of security guards and the police. Walls with mirrors were also suggested in stores, supermarkets and restaurants ; and in the general mall environment, displays with real time information showing what is happening in the mall as well as better maps to make it easier to orient oneself. Other suggestions included removing pop-up stores as well as temporary cafés in the middle of the corridors that negatively affect the movement of people and provide easy opportunities to steal. More guardianship could be promoted by providing seating options in the corridors, which is desirable for older adults and children. Crowded corridors were pointed out as a major problem but also entrances/exits , for example:

“Just at this café in the main corridor is extra crowded where there is a queue for the cashier on one side and the shop on the other side” (young woman, frequent visitor who lives close by),

which could potentially be mitigated by:

“More open spaces, wider walkways, enhanced entrances, with wider doors so it gets easier to get by” (middle age men who pass by the shopping mall on a daily basis).

Respondents suggested a number of target-hardening measures, including random bags checks at exits in stores and supermarkets . In order to make it easier to catch criminals, respondents also suggested changes in particular environments by improving lighting and reducing physical barriers and hiding spots, especially along corridors and other spaces to maximize natural surveillance. Problems of public disorder at entrances, particularly involving youths, could be tackled by involving youth organisations promoting, for instance, safety walks. A safety walk (or audit) is an inventory of the features of an area that affect individuals’ perceptions of safety (Ceccato & Hanson, 2013). In this particular case, safety walks could involve both youth and adults.

Other suggested changes involved major modifications to the shopping centre environment, including wider passageways. Others felt that the mall is too enclosed and suggested more open spaces within the mall as well as changes in the stores (one exit instead of multiple ones). Several suggested noise-reducing materials being used inside the mall, especially around the food court. Some suggestions even went beyond changes to the physical environment, such as working actively with social unrest in the surrounding area by creating activities for youths, especially with those who are at risk of offending.

Discussion of the Results

Shopping centre visitors vary in their declared perceived safety of the shopping centre. Following previous research (Box, Hale, & Andrews, 1988; Hale, 1996; Maxfield, 1984; Pain, 1997) and confirming Hypothesis 1, respondents who are familiar with the shopping centre felt safer than those who come to the shopping less frequently. There were also indications of altruistic fear (Trickett, 2009), where people fear for their family and friends. People born outside Sweden are more worried about their safety; younger people, as expected, are less worried; and those who declare feeling less safe are often female. There are several explanations as to why women feel less secure than men (for a review, see Pain, 1997). One explanation is that women are significantly more likely than men to be exposed to sexual violence, a fear that is transferred to other types of victimization. Women also tend to underestimate their own ability to defend themselves against physical attacks, whilst men often overestimate their ability. Another explanation is that media images depict women as vulnerable in a world where mobility and victimisation are also gendered (Ceccato, 2017).

Overall, respondents’ perceptions of safety are also influenced by the mall’s environmental attributes in different parts of the shopping centre, corroborating Hypothesis 2. Similar to Poyser’s (2004) findings, the layout and design of transition areas (corridors, stairs), of public spaces (the food court in particular), and of entrances and immediate surroundings (illumination, events of public disorder, public square and underground station) did affect perceived safety. Those who live close by are more worried about safety conditions in the shopping centre than those who live far away, perhaps because the shopping centre ‘absorbs’ (Bowers, 2014) some of the criminogenic conditions of the surrounding areas. However, visiting the shopping centre more frequently makes visitor feel safer, most probably because they become more familiar (Jackson et al., 2017) with the environment.

Very often people would declare feeling generally safe in the shopping centre (85 per cent) but still would point out places in the shopping centre that trigger unsafe feelings. This is probably because, as suggested in the literature of fear of crime, overall perceived safety encompasses additional triggers other than the individuals’ experiences of the environment in which she/he spends time. Having been a victim of a crime (5 per cent) or a witness of crime (21 per cent) negatively affects declared perceived safety. Respondents had most often been victims of pickpocketing and theft, and had witnessed shoplifting , robbery and fights.

By comparing incident figures and visitors’ perceived safety, one notices that there is a mismatch between where most crimes are recorded (entrances and public places) and where respondents declared witnessing the most incidents (functional spaces). This can be explained by the fact that visitors’ perceptions are formed by more serious incidents (robbery with the use of a weapon) that happen in jewellery and electronic stores (functional spaces) and not by minor events at entrances or the food court (incidents of public disturbance in the restaurant area). Moreover, even if they had witnessed most incidents in functional spaces, the places they felt the most unsafe were entrances, overlapping to some extent the geography of crime records (see Chap. 7). Here, fear is triggered by the process of othering, or ‘fear of others’ (Sandercock, 2005); homeless people blocking the entrances, drug/alcohol addicts, and noisy youth trigger feelings of worry. Moreover, as expected in Hypothesis 4, visitors adopt behaviour avoidance (Riger et al., 1982; Skogan & Maxfield, 1981), either by avoiding certain areas in the shopping mall or certain times of the day, such as late evening hours.

Similar to findings by Kajalo and Lindblom (2016) in Finland, visitors have different preferences with regards to improvement of safety conditions in the context of shopping malls: surveillance , anonymity reduction measures and target hardening . However, they do not differ in all respects. Most suggestions relate to the improvement of formal and informal surveillance (by implementing CCTV cameras, security guards, mall hosts at entrances, staff in toilets, no physical barriers or disruption to the field of view).

Conclusions

Contributing to better knowledge of the perception of safety of shopping centre visitors, this exploratory study demonstrates that safety in a shopping centre, taken here as fear of crime, is dependent on multi-scale factors. Some of these are related to the characteristics of the individuals themselves, while others, are associated with the environmental conditions at work at various levels in the facility and its immediate surroundings, some of them varying over time. While this study is of limited generalizability due to its small sample size (respondents and area of study), it could serve as the basis for future large-scale surveys of shopping malls in Sweden and abroad.

Planning for a safe shopping environment is part of creating an entertaining shopping experience. In order to do that, as suggested by Kajalo and Lindblom (2016, p. 227), ‘shopping malls should know their customers better’. However, customers are only one group of people who make use of these public spaces. When talking about everyone’s right of access to safe public areas, it is important to ask ourselves as planners; for whom do we want to provide safety? As in many other public places, entrances to shopping centres accommodate groups that are often viewed as a security problem rather than as individuals who have a right to feel safe. In these circumstances, getting right who is responsible for what (e.g. delivering security services for whom, where and when) at shopping facilities and their surrounding areas is essential. Ekblom (1995) reminds us that despite these uncertainties, what remains is the fact that good design , including detailed attention to the layout and good management practices, can be the key to accommodating different interests and ensuring a safe environment for all.

Notes

- 1.

In this chapter, the terms shopping centre, shopping mall, shopping premises and shopping facility are used interchangeably, as synonym.

References

Armitage, R. (2013). Crime Prevention through Housing Design: Policy and Practice. Basingstoke; New York: Palgrave.

Bamfield, J. (2012). Shopping and Crime. Basingstoke; New York: Palgrave.

Beck, A., & Willis, A. (1995). Crime and Security: Managing the Risk to Safe Shopping. Leicester: Perpetuity Press.

Bowers, K. (2014). Risky Facilities: Crime Radiators or Crime Absorbers? A Comparison of Internal and External Levels of Theft. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 30(3), 389–414.

Box, S., Hale, C., & Andrews, G. (1988). Explaining Fear of Crime. British Journal of Criminology, 28(3), 340–356.

BRÅ – Brottsförebyggande rådet. (2016). Utsatta Områden - Stockholm. Retrieved August 29, 2017, from http://www.bra.se/bra/brott-och-statistik/statistik/utsatta-omraden/stockholm.html

Brantingham, P., & Brantingham, P. (1995). Criminality of Place: Crime Generators and Crime Attractors. European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research, 3(3), 1–26.

Ceccato, V. (2014). Ensuring Safe Mobility in Stockholm, Sweden. Municipal Engineer, 168(1), 74–88.

Ceccato, V. (2016). Visualisation of 3-Dimensional Hot Spots of Crime in Shopping Centers. Paper Presented at the Retail Crime: International Evidence and Prevention, Stockholm.

Ceccato, V. (2017) Foreword: Women’s Victimisation and Safety in Transit Environments. Crime Prevention and Community Safety, 19(3–4), 163–167. (Special Issue: Women’s Victimisation and Safety in Transit Environments: An International Perspective).

Ceccato, V., & Hanson, M. (2013). Experiences from Assessing Safety in Vingis Park, Vilnius, Lithuania. Review of European Studies, 5(5), 1–16.

Clarke, R. (1989). Theoretical Background to Crime Prevention through Environmental Design (CPTED) and Situational Prevention. In S. W. L. Hill (Ed.), Designing Out Crime (pp. 13–20). Brisbane, Australia: Australian Institute of Criminology.

Cohen, L. E., & Felson, M. (1979). Social Change and Crime Rate Trends: A Routine Activity Approach. American Sociological Review, 44(4), 588–608.

Cozens, P. M., Saville, G., & Hillier, D. (2005). Crime Prevention through Environmental Design (CPTED): A Review and Modern Bibliography. Property Management, 23(5), 328–356.

Eck, J., Clarke, R., & Guerette, R. (2007). Risky Facilities: Crime Concentration in Homogeneous Sets of Establishments and Facilities. Crime Prevention Studies, 21, 225–264.

Eck, J., & Weisburd, D. (1995). Crime Places in Crime Theory. In J. E. E. D. Weisburd (Ed.), Crime and Place (pp. 1–33). Washington: NCJ.

Ekblom, P. (1995). Less Crime, by Design. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 539(1), 114–129.

Ekblom, P. (2013). Redesigning the Language and Concepts of Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design (CPTED). Paper Presented at the 6th Ajman International Urban Planning Conference 2013, United Arab Emirates.

Felson, M. (1987). Routine Activities and Crime Prevention in the Developing Metropolis. Criminology, 25(4), 911–931.

Gray, E., Jackson, J., & Farrall, S. (2008). Reassessing the Fear of Crime. European Journal of Criminology, 5(3), 363–380.

Grönlund, B. (2012). Is Hammarby Sjöstad a Model Case? Crime Prevention through Environmental Design in Stockholm, Sweden. In V. Ceccato (Ed.), The Urban Fabric of Crime and Fear (pp. 283–310). Netherlands: Springer.

Hale, C. (1996). Fear of Crime: A Review of the Literature. International Review of Victimology, 4(2), 79–150.

Hilborn, J. (2009). Dealing With Crime and Disorder in Urban Parks. Retrieved August 29, 2017, from http://www.popcenter.org/Responses/pdfs/urban_parks.pdf

Jackson, J., & Gray, E. (2010). Functional Fear and Public Insecurities about Crime. British Journal of Criminology, 50(1), 1–22.

Jackson, L., Harris, C., & Valentine, G. (2017). Rethinking Concepts of the Strange and the Stranger. Social & Cultural Geography, 18(1), 1–15.

Johansson, E. (2016). Trygghet i Köpcentrum: En Fallstudie i Stockholm, Sverige. (Samhällsbyggnad Civilingenjörsexamen - Samhällsbyggnad), KTH, Stockholm.

Kajalo, S., & Lindblom, A. (2016). The Role of Formal and Informal Surveillance in Creating a Safe and Entertaining Retail Environment. Facilities, 34(3/4), 19–232.

Koskela, H. (2000). The Gaze Without Eyes: Video-surveillance and the Changing Nature of Urban Space. Progress in Human Geography, 24(2), 243–265.

Lagrange, R. L., & Ferraro, K. F. (1989). Assessing Age and Gender Differences in Perceived Risk and Fear of Crime. Criminology, 27(4), 697–720.

Lindblom, A., & Kajalo, S. (2011). The Use and Effectiveness of Formal and Informal Surveillance in Reducing Shoplifting: A Survey in Sweden, Norway and Finland. The International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research, 21(2), 111–128.

Maxfield, M. G. (1984). Fear of Crime in England and Wales, Home Office. Research and Planning Unit, Study No. 7 (Vol. 81). London: H.M.S.O.

Pain, R. (2000). Place, Social Relations and the Fear of Crime: A Review. Progress in Human Geography, 24(3), 365–387.

Pain, R. (2009). Critical Geopolitics and Everyday Fears. In M. Lee & S. Farrall (Eds.), Fear of Crime: Critical Voices in an Age of Anxiety (pp. 45–58). New York: Routledge-Cavendish.

Pain, R. H. (1997). Social Geographies of Women’s Fear of Crime. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 22(2), 231–244.

Poyser, S. (2004). Shopping Centre Design, Decline and Crime. International Journal of Police Science and Management, 7(2), 123–125.

Reynald, D. M. (2014). Informal Guardianship. In G. Bruinsma & D. Weisburd (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Criminology and Criminal Justice (pp. 2480–2489). New York, NY: Springer New York.

Riger, S., Gordon, M. T., & LeBailly, R. K. (1982). Coping with Urban Crime: Women’s Use of Precautionary Behaviors. American Journal of Community Psychology, 10(4), 369–386.

Salcedo, R. (2003). When the Global Meets the Local at the Mall. American Behavioral Scientist, 46(8), 1084–1103.

Sandberg, P. (2016). Crime and Safety Issues in a Swedish Shopping Centre. Paper Presented at the Retail Crime: International Evidence and Prevention, Stockholm.

Sandercock, L. (2000). When Strangers Become Neighbours: Managing Cities of Difference. Planning Theory & Practice, 1(1), 13–30.

Sandercock, R. J. (Ed.). (2005). Difference, Fear and Habitus, a Political Economy of Urban Fear. Aldershot: Ashgate.

Savard, D. M., & Kennedy, D. K. (2014). Crime and Security Liability Concerns at Shopping Centers. In K. Walby & R. K. Lippert (Eds.), Corporate Security in the 21st Century: Theory and Practice in International Perspective (pp. 254–275). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Scott, N. K. (1989). Shopping Centre Design. London: Van Nostrand Reinhold.

Skogan, W. G., & Maxfield, M. G. (1981). Coping with Crime - Individual and Neighborhood Reactions. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Swedish Trade Federation. (2015). Svensk Handels Undersökning om Stöldbrott i Butik 2015. Stockholm. Retrieved October 15, 2016, from http://www.svenskhandel.se/verksam-i-handeln/sakerhetscenter/amnesomraden/stolder--snatterier/

Trickett, L. (2009). ‘Don’t Look Now’ – Masculinities, Altruistic Fear and the Spectre of Self: When, Why and How Men Fear for Others, Crimes and Misdemeanours. SOLON, 3(1), 82–108.

Valentine, G. (1990). Women’s Fear and the Design of Public Space. Built Environment, 16(4), 288–303.

Acknowledgements

We thank the reviewers of this chapter as well as comments provided by the audience in the poster session in the seminar “Retail crime: International evidence and prevention” that took place in Stockholm, Sweden, 15th September 2016. Many thanks to shoppers and visitors of this shopping centre who spent time answering the questionnaire.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

This chapter is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

Copyright information

© 2018 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Ceccato, V., Tcacencu, S. (2018). Perceived Safety in a Shopping Centre: A Swedish Case Study. In: Ceccato, V., Armitage, R. (eds) Retail Crime. Crime Prevention and Security Management. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-73065-3_9

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-73065-3_9

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-73064-6

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-73065-3

eBook Packages: Law and CriminologyLaw and Criminology (R0)