Abstract

Increasing resources are being allocated both to the management and research of biological invasions in South Africa. However, as with many natural resource management and conservation programmes globally, the question remains as to what extent the science provides the necessary answers for management, and whether it influences decision-making. This frequently presents as a gap between knowledge generation and application of research outcomes (‘knowing-doing gap’). The ideal scenario, a two-way transfer of knowledge along a continuum between science and management (‘knowing-doing continuum’), would allow for dialogue between all role-players that will not only transfer research results in support of management, but communicate management needs to scientists. This chapter explores how well this continuum has operated in South Africa with regard to biological invasions. Professionals employed in different positions along a continuum of basic or applied research to technology transfer and implementation are currently assessed with different performance measures. This drives different behaviours, which in turn can impede smooth integration. To counteract this, different types of communication structures have been developed, although many have not persisted. The most successful and enduring appear to be voluntary forums or conference series where researchers and managers are regularly exposed to each other’s challenges. Scientists who are embedded within management agencies (for example, Scientific Services units within national parks and provincial conservation agencies) appear to be well-placed to bridge the gaps that exist, but mechanisms to evolve into a true knowing-doing continuum still need to be sought for the South African context. To be more relevant, researchers need to draw on the experience of managers, better understand the context within which managers operate, and by which they are constrained, while policy-makers may have to become more willing to adapt approaches when research suggests that such changes would be warranted if certain goals are to be achieved.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Numerous studies across the resource management and conservation landscape call for the need for a credible, robust body of science to underpin decision-making (Cook et al. 2013; Dicks et al. 2014). The growing concerns about the impact of biological invasions creates an increasing need for scientific knowledge to support the development of effective policies and management strategies (Esler et al. 2010). Policy-makers and managers require information that will underpin their decisions with robust scientific advice, while scientists wishing to contribute to global conservation efforts aim to provide information that is internalised and used. The disconnect between these spheres of practice results in a “knowing-doing” gap (Esler et al. 2010; Matzek et al. 2014) that can potentially present barriers to the successful outcome of management programmes and the development of effective policies (Cook et al. 2013). As discussed below, these barriers include differences in reward systems and time frames, as well as the complexity of managing natural resources (Ntshotsho et al. 2015). South Africa provides a good opportunity to explore this issue with regard to biological invasions, given its long invasion history, numerous invasive alien species, high native species richness, large and long-running research and control programmes, and an extensive network of engaged researchers (van Wilgen et al. 2014; Abrahams et al. 2019).

Considerable funding and resources are dedicated to research about, and management of, biological invasions in South Africa. From the management perspective, for example, the government’s Working for Water programme has spent ZAR15 billion on alien plant control operations across South Africa since 1995 and has conducted control operations on an average of about 200,000 ha per year (van Wilgen et al. 2020, Sect. 21.2). In 2018, the Department of Environmental Affairs ’ Natural Resource Management programmes provided ZAR90 million in research funding annually three, while the Centre for Invasion Biology (C·I·B) operates on a core annual budget of ZAR25 million. In order to generate knowledge that is actionable, it needs to be relevant and context-specific, therefore a dialogue between scientists and managers is needed to co-produce, translate, and facilitate the effective utilisation of new knowledge (Roux et al. 2006; Esler et al. 2010).

In this chapter, we describe the organisational environment within which invasive species research and management operate in South Africa. We discuss how this “knowing-doing continuum” facilitates the transfer of knowledge between researchers and managers across a network of basic and applied ecologists, policy-makers, planners and managers, and we identify weaknesses and discuss how they can potentially be improved.

2 The Role-Players and Challenges in the Knowing-Doing Continuum in South Africa

Many factors influence the pathways along which creative ideas in scientific journals must travel before they can be practically applied. In addition, the requirements of managers often do not reach researchers. The factors that influence information flow may include reward systems, time frames, and the fact that natural resource management is complex and involves more than science (Ntshotsho et al. 2015). Additionally, this journey operates within prevailing socio-political values (Carruthers 2017; Ntshotsho et al. 2015). Research is not always driven by practical need; it may be theoretical or driven by curiosity alone. Those who fund research may require specific outputs, which are not necessarily applied or aligned with policy and management needs. In cases where research is driven by curiosity alone, an applied idea could be a by-product that may, or may not, find its way into the scientific literature. Those ideas that are published are not necessarily seen by, or accessible to, potential end-users (Esler et al. 2010). Managers require rapid, implementable solutions and access to knowledge. Unless knowledge is co-created or actively sought and translated for use by management, practical innovations reported through scientific literature may remain inaccessible (Roux et al. 2006).

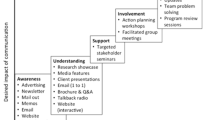

In South Africa, there are at least four broad groups of practitioner’s active along the biological invasion science-management continuum (Table 28.1). These are academic (usually university) scientists, science councils, researchers embedded in conservation agencies and managers (including policy-makers, planners and implementation managers). These groups produce and process information from basic research through to application (Fig. 28.1), which is broadly in line with South Africa’s National System of Innovation, overseen by the Department of Science and Innovation (NACI 2006).

Conceptual diagram illustrating the knowing-doing continuum, in which information flows in both directions between researchers and ecosystem managers. Different players (academics, researchers and managers) have a focus on different positions along the continuum (basic and applied research, technology transfer and implementation). The monitoring of outcomes will allow for feedback to researchers, who in turn could adapt research to address emergent needs, thus underpinning evidence-based, adaptive management

Each of these groups is largely driven by different reward systems, which dictate their priorities, how (or whether) knowledge is communicated between them, and their relative contribution to policy and management decisions (Table 28.1). Research can further be broadly separated into ‘basic’ and ‘applied’, the former referring to research aimed at advancing the underlying theoretical knowledge base, while applied research is largely orientated towards problem-solving. Universities that do basic and applied research are principally funded by the Department of Higher Education and Training, whose grants to the universities are proportional to the number of papers published in recognised, peer-reviewed journals, and to the number of students who graduate. The objective of this system is to generate basic and applied research, and to build capacity through the training of graduates. However, the nature of the research itself, or the topics of dissertations, are not always considered. The performance of researchers is therefore assessed by the number of papers produced and the standing of the journal according to various ‘impact factor’ ranking systems, and not necessarily by the focus of the research itself.

The science councils (e.g. the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research, or the Agricultural Research Council) receive some funding from the central government, but are expected to secure an increasing proportion of their funding from external clients. Science councils were established to conduct applied research and to develop science-based solutions to issues deemed to be important (Scholes et al. 2008). To this end, much of their research is funded by external clients, an approach intended to ensure that the research itself has relevance. The research contracts between science councils and external clients are normally quite specific with regard to the required outputs. In the case of biological invasions, clients include the government’s Natural Resource Management Programmes (Working for Water) or international funders. Researchers in science councils are evaluated in terms of meeting “sales targets” (i.e. securing contracts with external funders) and “client satisfaction” (i.e. whether or not the client approved of the products produced or service provided). With respect to biological invasions, clients have usually been satisfied with research findings that clearly demonstrate the magnitude of negative impacts of invasive species, as such findings can be used to justify requests for greater funding for control measures. This work involves both basic research and the synthesis of findings. It includes, for example, demonstrations that alien plant control should deliver water at lower cost than building new dams (van Wilgen et al. 1997) or that biological control delivers high returns on investment (van Wilgen and De Lange 2011). They seldom assess the effectiveness of management systems that may have been developed, as the clients, in turn, are often measured by input rather than output variables (e.g. jobs created or money spent, Table 28.1).

Managers of government-funded alien plant control projects have very clear targets that need to be achieved as a measure of success—the number of hectares cleared, the cost per person-day achieved (which has to be kept low to increase the number of people employed) and money spent (if the money allocated to a project is not effectively disbursed, then the person-days target will be missed). These are input and output-based metrics, and outcome metrics such as restored water flow and quality, or biodiversity and ecosystem services that represent the real long-term success of control are not considered. The response by an interviewee during a study on adaptive management of invasive plants (Loftus 2013) clearly illustrates some manager’s challenges: “They [decision makers and politicians] couldn’t care about the environment, all they care about is person-days … If you can’t put a price tag on it that says ‘person-days’ then they’re not interested.”, “… you focus only on those targets … you chase person-days and hectares, and your budget must be spent on time … you are always chasing this.” In this environment, it is perhaps not surprising that on-the-ground managers find little time to focus on improving the effectiveness of alien species control projects by incorporating the latest research findings, as it will do little to improving their personal performance ratings.

Agency-embedded scientists perhaps provide one model that can successfully integrate science and management, by virtue of being employed by a management organisation to advise and support policy and management (Cook et al. 2013; Roux et al. 2019). Agency-embedded scientists practice technology transfer, and occupy a position on the knowing-doing continuum between applied research and implementation. Agency scientists also carry out their own problem-orientated research that can be focused directly on the needs of management of the area. For example, a study on published research in South African National Parks (SANParks, van Wilgen et al. 2016a) found that embedded authors are “ … more highly connected and influential than external researchers, leveraging and connecting many research projects … ”, and therefore able to direct some of the science agenda to the park’s management needs. Similarly, a review of ecological research and conservation management in the Cape Floristic Region (van Wilgen et al. 2016b) stated that it was “… clear from the experience that followed the publication of the Wicht Committee’s (Wicht 1945) report that much benefit was gained from the long-term partnership between research and management …”. It was further noted that (with respect to the development policies and management plants for catchment areas) “throughout this … cycle of policy-making and planning, [embedded] research scientists made contributions based on the scientific knowledge of the day; each policy and plan was completed only after consultation with the research scientists” (van Wilgen et al. 2016b).

3 Efforts to Promote the Exchange of Ideas Between Managers and Researchers

Despite the fact that performance measures differ substantially between the four groups, and that these do not necessarily promote an effective knowing-doing continuum, it is also true that individual researchers and managers share common goals regarding the management of biological invasions. In South Africa, a relatively small and well-connected community of practitioners across all the four groups provides opportunities for individuals to interact and exchange ideas on a fairly regular basis, despite being employed by different agencies (van Wilgen 2020, Sect. 2.14). A variety of fora, symposia, panels and working groups have been initiated over time to promote and share expertise between managers and scientists (Table 28.2). In addition, there are examples of direct collaboration between researches and managers, for example the establishment of mass-rearing facilities for biological control agents (Box 28.1).

Box 28.1 Mass-Rearing of Biological Control Agents: An Example of the Direct Implementation of Research Results

Until the mid-1990s, most South African work on weed biological control was conducted by researchers, including the mass rearing, release and post-release monitoring of agents. By-and-large, this worked well, with a relatively high rate of establishment of agents, but for some agents (e.g. Pareuchaetes species on Chromolaena odorata, Triffid Weed) establishment could only be achieved by large-scale mass-rearing which was beyond the capacity of research organisations. As control programs became more widespread in South Africa after 1995, the demand for agents increased substantially. An ‘implementation’ programme was thus set up in the late 1990s (Gillespie et al. 2004), with the aim of mass-rearing biological control agents for release, and monitoring their establishment success. Several mass-rearing centres were set up around the country, and implementation officers were employed. Interaction between researchers and implementers was encouraged, with both implementers and researchers attending the annual meeting on biological invasions (Table 28.2). Although this programme has facilitated the release of biological control agents throughout the country, the project has faced challenges. Several mass-rearing centres failed due to funding issues; most lacked sufficient biological control expertise; implementation officers were assigned additional responsibilities not relevant to mass-rearing; and structured cooperation and feedback loops between researchers and implementers were lacking (e.g. introducing uncertainty about which agents to mass-rear, how many to release, or when the use of biological control was indicated). Often, inadequate distinction was made between agents whose establishment or efficacy was not yet proven, and agents which had already been shown to be effective but needed further redistribution. There was thus ongoing uncertainty about where the dividing line between research and implementation lay on the continuum between these activities. Nevertheless, the implementation programme has substantially increased the number of biological control releases made in the country and the number of plants with active biological control implementation programmes in operation, and has doubtlessly improved the level of control for many invasive alien plant species (Zachariades et al. 2017).

One of the oldest and most successful symposia originated in 1973, in the form of an annual meeting of biological control scientists (Wilson et al. 2017). These meetings ultimately grew into much larger meetings where the integration of science and management were discussed. They have led to the development of a common understanding regarding the need for biological control, leading to increased and sustained funding for research (Moran et al. 2013), and the development of joint approaches to implementation (Box 28.1).

Other groups and regional meetings have been effective in stimulating applied research and its uptake, for example the Cape Invasive Animal Working Group (van Wilgen et al. 2014; Davies et al. 2020) and the KwaZulu-Natal Invasive Alien Species Forum . Other taxon-specific national working groups have also been established to focus research efforts and provide fora for stakeholders to discuss issues, for example the Cactus Working Group (Kaplan et al. 2017) and the Alien Grass Working Group (Visser et al. 2017). A long established forum—the Fynbos Forum —was initiated in the 1970s (Gelderblom and Wood 2018). The Fynbos Forum was considered to play “… a unique role in bringing together participants from science, management, policy and planning to extend the boundaries of knowledge and practice—promoting a culture of collaboration …” (Gelderblom and Wood 2018).

Working for Water also initiated a biological control research advisory panel (RAP) in 1997 to guide the direction of research and to review the quality of outputs. Prior to this intervention, the selection of plants targeted for biological control was made entirely by the research community. When the government’s Working for Water (WfW , see van Wilgen and Wannenburgh 2016) programme was initiated in 1995, the manager of the Weeds Research Division of the Plant Protection Research Institute (PPRI), Dr. Helmuth Zimmermann , approached WfW’s Steering Committee, outlining the available expertise in the field of biological control, and stressing the importance of the approach. As a result, Working for Water funded (and continues to fund) research into biological control (van Wilgen et al. 2016c ; Moran et al. 2013). Later, RAPs were set up for other areas of research, including ecological, hydrological, social and operations research. The biological control RAP has remained active for over 20 years, but the other RAPs were arguably less influential. In 2014 RAPs (other than the biological control RAP) were replaced by a forum that intended to exchange information between managers, researchers and planners (MAREP meetings ).

MAREP meetings were modelled on similar meetings that were held between managers, planners and embedded researchers in the Department of Forestry in the 1970s and 1980s. The system was adopted by WfW in 2014, and ran until 2017. On average, WfW’s MAREP meetings attracted 30 participants, of whom 20 were managers, nine were researchers and one was a planner. RAP meetings were discontinued after 2017, as senior managers in WfW felt that it would be more useful to invest research funding into “rapid research” with a focus on ad hoc problems, as there was a perception that the RAP process was too slow (C Marais pers. comm. to AW).

4 Manager’s Perceptions and Needs

There have been a limited number of studies that have attempted to address aspects of the knowing-doing gap in biological invasions in South Africa. Esler et al. (2010) concluded, based on a survey of relevant scientific papers in the field of invasion biology in South Africa, that most research had been aimed at “knowing” rather than at “doing”. “Doing” papers were poorly represented in the scientific literature, and the scale of their emphasis was not local, i.e. researchers tended to focus on broad principles or processes over relatively large spatial scales, while managers often experienced problems with specific species in particular local areas, and where they found it difficult to apply broader concepts. Shaw et al. (2010) used structured symposia involving managers and researchers to explore how well such interventions might facilitate knowledge transfer. They concluded that the exchanges were useful, but that the use of complex terminology and a lack of context-specific solutions hampered knowledge transfer. McConnachie and Cowling (2013) carried out an exercise to establish whether managers would be willing to change their beliefs after being exposed to evidence-based findings. When managers were shown that their historical control efforts had not been as effective as they believed, they were willing to revise their perceptions. Surprisingly, though, they still believed it would be possible to achieve very ambitious goals, despite evidence to the contrary. There are a number of possible explanations for this result. The first is “optimism bias”, a well-documented phenomenon in which managers over-estimate their ability to achieve targets; secondly, there could be an anchoring effect, where managers find it difficult to move too far from their original goals; and finally it may be because of a high degree of perceived uncertainty in the research results (McConnachie and Cowling 2013, and references therein). Ntshotsho et al. (2015), in response to complaints from researchers that their findings were rarely used, investigated the factors that constrained manager’s ability to use research findings. They concluded that “the use of scientific evidence is limited by the fact that the management of natural resources involves much more than science”. The social context within which managers have to work, the bureaucracy that they have to deal with, and the fact that they have to achieve multiple, often competing, goals all constrain the effective use of research results.

A study in 2018 on the value of research to WfW project managers (AW unpubl data) aimed to determine how managers use the scientific literature and what questions managers would like to have answered to be more effective at controlling invasive alien species. Questionnaires were sent to 300 WfW managers, and of the 66 respondents about 35% cited “Websites, newsletters and best management practice guidelines” as their primary source of information (Fig. 28.2). Thereafter, about 25% cited “Conversations with other managers” and only 17% indicated that they consulted peer-reviewed journal articles. Nearly 40% indicated that they did not have access to peer-reviewed journals (although there was no indication of whether they would use the articles if they did have access). Only about 25% felt that they did not have the necessary expertise to understand the articles, or felt such content was not of use to them. More than a third of the respondents indicated that they did not have time to search for and read articles. This is similar to the findings of Loftus (2013) regarding the adaptive management of biological invasions in South African National Parks, where all interviewees cited lack of time for reflection, knowing there are problems but not being able to experiment to improve outcomes. These challenges are not only a South African problem. In a similar assessment of land managers in The Nature Conservancy (Kuebbing and Simberloff 2015), 94% of the managers stated that their primary information source was from colleagues and other contacts that manage alien species. Only 45% reported that they also use peer-reviewed literature. A survey of Californian managers of biological invasions also revealed that peer-reviewed journals were seldom used by managers as a source of information, and that they relied primarily on informal conversations with other managers, and their own experiments or monitoring to inform their work (Matzek et al. 2014).

5 Formulation of Research Questions by Managers

In the study on the value of research to WfW project managers (AW unpublished data), 45% of the managers agreed with the statement that “manager’s priorities are well-represented in research agendas”. In response to the question “What research questions do you most need answered, in order to be effective at managing invasions?” the respondents suggested 86 topics (see Box 28.2 for a sample). These were then categorised into three groups, with basic science making up 20% of the topics, applied science making up 34%, and interdisciplinary research constituting 46% of the topics. Of the basic science topics (Fig. 28.3a), the most important were on the range and abundance of invasive alien plants (>30%), followed by biological control (>20%, although biological control can also be considered to be applied research). Regarding applied research (Fig. 28.3b), treatment effectiveness appears to be a high concern, with >70% of the suggested research topics. Interdisciplinary research (Fig. 28.2c) was dominated by a need for research around strategy development. Interestingly, while 45% of the managers felt that their priorities were represented, only 17% of the managers used peer-reviewed journal articles as their source of information (Fig. 28.1).

Box 28.2 A Sample of Research Questions Identified by Managers

We requested managers to identify research questions that they regarded as important, and that would provide information that could help them to improve the effectiveness of their alien species control projects. We received 86 suggestions, and a sample of these is presented here, categorised by type and topic of research (see also Fig. 28.2). We have edited managers’ short-hand notes for clarity.

Type of research | Topic of research | Questions |

|---|---|---|

Basic | Range and abundance | Is it possible that the invasive alien trees can be completely cleared? |

What drives the distribution and spread of invasive alien plants? | ||

What is the extent of biological invasions, and what will it cost to manage them? | ||

Biological control | What impact have the biological control agents released over last 60 years had? | |

How do different biological control agent species interact on same target plant? | ||

How does climate affect the effectiveness of biological agents in different parts of the country? | ||

Impact | What are the impacts of management of alien plants on water resources? | |

Global change | How will alien biota respond to climate change ? | |

Emerging species | Which alien species should we be managing now, before they become a problem? | |

Applied | Treatment effectiveness | What other effective methods can be utilised without applying herbicides, i.e. reducing the herbicide footprint and funds spent on herbicide, but still achieving our management goals? |

How can we assess the effectiveness of control methods? | ||

Is it possible to effectively control Parthenium hysterophorus? If yes, how, and if no, what are the potential problems? | ||

Can we develop a proper tool to accurately estimate alien plant density? | ||

Can we develop monitoring systems that are easy to understand, cost effective and practical to implement? | ||

How effective has the early detection and rapid response programme been since inception? | ||

How successful has the integration of mechanical and chemical control with biological control been? | ||

Are our current invasive species clearing methods having a positive impact on biodiversity conservation and on ecosystems? How can this be maximised and be made part of the prioritisation process? | ||

Can frequent (short return-interval) fires be used to control pines (Pinus species) and hakea (Hakea species) that are inaccessible? | ||

Rehabilitation | How can we rehabilitate sites post-clearing, especially where the soil nutrients have been depleted? Also rehabilitation in protected areas . | |

How can we improve the prioritisation of invasive alien plant control so as to best restore ecosystems? | ||

Does clearing of invasive alien plants help to increase the population of native plants and, if not, what should be done to stimulate the population growth of native plants? | ||

Cost-effectiveness | How much does it cost to manage a species at different stages of density and invasion? | |

Can we develop cost-effective methods to deal with dense infestations of pines (Pinus species) and hakea (Hakea species) that are inaccessible; evaluating the short-interval controlled burns? | ||

Interdisciplinary | Resource economics | What is the economic value of riparian restoration verses the economic loss through degradation as a result of riparian invasion? |

How do we ensure the cost-effectiveness of invasive species control over time? | ||

Can we improve the confidence levels of ecological assumptions in economic analysis of land rehabilitation and maintenance? | ||

Capacity-building | Can we evaluate, using case studies, how effective we have been in capacitating local stakeholders to be able to carry out effective project planning and implementation? | |

How effectively, or to what extent, have environmental education initiatives contributed to the fight against invasive species? |

6 Management Recommendations Made by Researchers

Many papers published by researchers in the field of biological invasions contain recommendations for managers. In some cases, these recommendations are quite detailed, while in others they appear almost as an afterthought arising from the main research topic. Almost universally, these recommendations are not directly adopted by managers, for a number of reasons, discussed below. A study by one of us (Abrahams et al. 2019) assessed the output from 364 scientific journal articles funded or co-funded by WfW over 20 years (1997–2017). An assumption may be made that WfW provided funds for studies that were largely intended to benefit the programme’s implementation. However, the study showed that only about 55% of the articles made explicit recommendations towards management practices, strategy, or future research needs. Of the 201 articles that did make recommendations, mechanical and chemical control (27.5%), biological control (26.5%), and improving monitoring efforts (21%) were the most frequently-mentioned. With respect to management strategy , 24.5% of the articles recommended improvements to strategy development and management planning. The topics covered by this research were all important priorities for managers, who have an ongoing need for research support (see Fig. 28.2 and Box 28.2). This includes the adoption of adaptive management and participatory approaches to management, and the need for the development of species, area, and pathway-based management strategies . Researchers recognised the need to collaborate with managers and other stakeholders, as suggested by 23.1% of articles, in the monitoring of the effectiveness of control measures, in such a way that adaptive management can be promoted and used for controlling invasions.

Although there is a recognised need for guidance from research, a number of important obstacles to the uptake of recommendations are evident. While the number of recommendations and other information available to guide management decision-making is growing, the information is still largely inaccessible. Only 27.2% of all the articles assessed were published in open-access journals (BA unpubl data), making the remaining research unavailable to those without journal subscriptions. Furthermore, WfW , through several associated websites, have only made 4.4% of the 364 articles that they funded or co-funded available to their managers. Research published in ‘grey literature’, also tends to be inaccessible even when funded by government (Lawrence et al. 2015). It would therefore be naive to expect that all managers would have the time, or the ability, to locate recommendations relevant to their particular issues from widely scattered and often inaccessible sources. As such, there are increasing calls for the improvement of information access and exchange between stakeholders (23.1% of articles containing management recommendations) to improve the uptake of knowledge. Clearly, making recommendations to managers in research publications, while important, remains a first step, and much more needs to be done to ensure eventual uptake.

7 Researcher’s Recommendations and Managers Needs

There are many critiques in the academic literature about the failure of managers to apply research findings for improving implementation, but in many cases scientists fail to understand and appreciate the environment in which managers have to make urgent, short-term decisions (Ntshotsho et al. 2015). South Africa’s management of invasive alien plants, almost exclusively funded by WfW , has been applauded globally (e.g. Koenig 2009). Despite this recognition, there are challenges and problems. Studies that have assessed management effectiveness have shown that the cover of invasive alien plants has been successfully reduced in some localised areas, but it continues to grow in others (van Wilgen et al. 2020, Chap. 21; van Wilgen and Wilson 2018). Currently, mechanical and chemical control measures have largely failed to check plant invasions at a national scale. Some of the contributing factors include the absence of effective prioritisation, goal-setting and planning; monitoring of inputs rather than of outcomes (i.e. reductions in the range and impacts of invasive alien species); multiple goals that lead to confusion over priorities; the fact that the actual costs of control far exceed the estimated costs; a failure to adhere to accepted best practices and standards; and complex contracting and employment models.

Does the identification and publication of these “contributing factors” filter through to managers, and if so, have they changed the way in which they operate as a result? One problem is that these studies often make recommendations that do not consider additional social, and operational demands, and that make it difficult for managers to accommodate suggestions (Ntshotsho et al. 2015). Another is that the published papers may not have come to the notice of managers. However, there are examples of recommendations that have emerged from research that managers are aware of, and that could have been implemented, but have not. For example, van Wilgen et al. (2016a) suggested that “The essential element of an improved management approach would be to practice conservation triage, focusing effort only on priority areas and species, and accepting trade-offs between conserving biodiversity and reducing invasions.” This would in essence mean that managers would have to abandon projects in areas where they had worked for some time to be able to focus on others, and to cease control efforts on some species to be able to focus on others. Managers have proved to be very reluctant to do this, even when presented with clear evidence that current approaches will not succeed in containing the spread of invasive plants.

The situation in the Fynbos Biome provides an example, where projects are under way to clear invasive pines (Pinus) and wattles (Acacia ) from water catchment areas. In this biome, van Wilgen et al. (2016a) estimated that existing levels of funding were insufficient to bring the invasions under control, but recommended that steps could be taken to effectively reverse spread. The proposed steps included directing funds away from low priority areas to areas of higher priority, and to focus all effort on pines rather than wattles (because pines would potentially spread further, and, unlike wattles, they have no effective biological control in place). Managers are probably reluctant to do this because of “optimism bias” or “anchoring effects” (see Sect. 28.4), but there are other reasons. Foremost among these is that closing projects in low-priority areas to strengthen control efforts elsewhere would lead to the local loss of employment. Even though a similar number of jobs could be created in the high-priority area, such decisions would be highly unpopular politically, and are unlikely to be supported by senior bureaucrats or politicians.

The above brief discussion illustrates an important disconnect in the knowing-doing continuum. Researchers are understandably frustrated that their assessments of management progress (or lack of it), and their proposals for ways to address this seem to fall on deaf ears. On the other hand, as shown above, managers point to aspects of their work that are not considered by researchers (Ntshotsho et al. 2015). In addition, senior managers of biological invasions in South Africa repeatedly emphasise that the job-creation aspects of the programme are the most important to the politicians that hold the purse strings, and that if the researcher’s calls to direct funds to more efficient, but less labour-intensive solutions were heeded, then the levels of funding currently enjoyed could drop by orders of magnitude (GP Preston pers. comm. to BvW). The challenges of promoting uptake of evidence-based recommendations are not unique to South Africa. For example, in Australia, extensive government-funded and volunteer programs aimed at stopping the advance of invasive Rhinella marina (Cane Toads) failed to halt or even slow their spread. Despite clear scientific evidence that management could never be effective—given the fecundity of the species concerned—and that the ecological harm caused by R. marina was not as severe as predicted, aggressive control programs continued unabated for many years (Shine 2018). High-level leadership and intensive collaboration between senior players from the different sectors of the knowing-doing continuum in South Africa would be needed if the research is to remain relevant, and if evidence-based recommendations are to be adequately considered. Given that managers and researchers essentially share the same goals, this should be possible, at least through adopting a national-level adaptive management approach informed by all role-players, and aimed at continuous improvement.

8 Conclusions

In South Africa, all of the necessary elements of the knowing-doing continuum appear to be in place. Universities, science councils, embedded researchers and scientifically-trained managers all operate at different positions along the continuum. However, the performance measures used to evaluate individuals employed by these organisations differ substantially, and they drive different behaviours. As a result, there are often disconnects when it comes to knowledge-sharing between the four groups. On the positive side, though, there are many opportunities (regular symposia, fora and working groups) for scientists and managers to interact and exchange ideas. These ongoing opportunities for two-way communication along the knowing-doing continuum continue to promote information transfer and a sense of shared purpose. South Africa also has a relatively small and well-connected ecological community who, by-and-large, share common goals. This means, at least, there is broad agreement on desired outcomes, even if there are differences about the means by which they should or could be achieved.

A study by van Wilgen and Wilson (2018) argued that there are several weaknesses in South Africa’s approach to the control of biological invasions. They include a lack of clear goals; no, or inadequate medium-term plans; the vagaries of uncertain funding; and an almost total absence monitoring of outcomes. Without clear goals, and rigorous monitoring, the implementation of an effective system of adaptive management will remain elusive. Managers, policy makers and scientists therefore need to agree on achievable goals (Metzger et al. 2017). If a system of goal setting and monitoring can be agreed on, and implemented, this could pave the way for fruitful collaborations between researchers and managers. A start has been made by defining a set of national-level indicators of the status of biological invasions (Wilson et al. 2018), but much remains to be done.

In conclusion, it can be stated that the effective transfer of research results to support-evidence-based management will remain challenging in the field of biological invasion management in South Africa. There are gaps in the knowing-doing continuum, both because researchers do not always fully appreciate the complexities of the environments in which managers have to operate, because new research results are not always readily available to managers, and because managers are prevented from implementing recommendations because they have to meet additional competing goals (or, alternately, that they are reluctant to accept that their considerable efforts are not achieving the desired outcomes). Researchers should perhaps pay more attention to the ultimate outcomes of a failure to bring biological invasions under control, at least in priority areas. Indications are that losses of water resources, livestock production and biodiversity due to biological invasions could have enormous negative impacts on South Africa’s economy—and avoiding these is arguably far more important than maintaining a focus on short-term benefits, such as employment creation. The knowing-doing continuum, as we have framed it here, goes from basic researchers at one end to managers at the other, but clearly it needs to go further to include senior bureaucrats and politicians if progress is to be made.

References

Abrahams B, Sitas N, Esler KJ (2019) Exploring the dynamics of research collaborations by mapping social networks in invasion science. J Environ Manag 229:27–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2018.06.051

Carruthers J (2017) National Park Science. A century of research in South Africa. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108123471

Cook CN, Mascia MB, Schwartz MW et al (2013) Achieving conservation science that bridges the knowledge–action boundary. Conserv Biol 27:669–678. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.12050

Davies SJ, Jordaan M, Karsten M et al (2020) Experience and lessons from alien and invasive animal control projects in South Africa. In: van Wilgen BW, Measey J, Richardson DM, Wilson JR, Zengeya TA (eds) Biological invasions in South Africa. Springer, Berlin, pp 625–660. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-32394-3_22

Dean WRJ, Milton SJ (1999) The Karoo, ecological patterns and processes. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511541988

Department of Water Affairs and Forestry (DWAF) (2001) The Working for Water programme: annual research report 2000–2001. Department of Water Affairs and Forestry, Pretoria

Department of Water Affairs and Forestry (DWAF) (2003) The Working for Water programme: biennial research report 2001/02–2002/03. Department of Water Affairs and Forestry, Pretoria

Dicks LV, Walsh JC, Sutherland WJ (2014) Organising evidence for environmental management decisions: a ‘4S’ hierarchy. Trends Ecol Evol 29:607–613

Esler KJ, Prozesky H, Sharma GP et al (2010) How wide is the “knowing-doing” gap in invasion biology? Biol Invasions 12:4065–4075. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-010-9812-x

Gelderblom C, Wood J (2018) The Fynbos Forum: its impacts and history. Fynbos Forum, Cape Town

Gillespie P, Klein H, Hill MP (2004) Establishment of a weed biocontrol implementation programme in South Africa. In: Cullen JM, Briese DT, Kriticos DJ et al (eds) Proceedings of the XIth international symposium on biological control of weeds. CSIRO Entomology, Canberra, pp 400–406

Huntley BJ (1987) 10 years of cooperative ecological research in South Africa. S Afr J Sci 83:72–79

Kaplan H, Wilson JRU, Klein H et al (2017) A proposed national strategic framework for the management of Cactaceae in South Africa. Bothalia 47:a2149. https://doi.org/10.4102/abc.v47i2.2149

Koenig R (2009) Unleashing an army to repair alien-ravaged ecosystems. Science 325:562–563. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.325_562

Kuebbing SE, Simberloff D (2015) Missing the bandwagon: nonnative species impacts still concern managers. NeoBiota 25:73–86. https://doi.org/10.3897/neobiota.25.8921

Lawrence A, Thomas J, Houghton J et al (2015) Collecting the evidence: improving access to grey literature and data for public policy and practice. Aust Acad Res Libr 46:229–249. https://doi.org/10.1080/00048623.2015.1081712

Loftus WJ (2013) Strategic adaptive management and the efficiency of invasive alien plant management in South African National Parks. Thesis, Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University

Macdonald IAW (2004) Recent research on alien plant invasions and their management in South Africa: a review of the inaugural research symposium of the Working for Water programme. S Afr J Sci 100:21–26

Matzek V, Covino J, Funk JL et al (2014) Closing the knowing–doing gap in invasive plant management: accessibility and interdisciplinarity of scientific research. Conserv Lett 7:208–215. https://doi.org/10.1111/conl.12042

McConnachie MM, Cowling RM (2013) On the accuracy of conservation managers’ beliefs and if they learn from evidence-based knowledge: a preliminary investigation. J Environ Manag 128:7–14

Metzger JP, Esler KJ, Krug C et al (2017) Best practice for the use of scenarios for restoration planning. Curr Opin Environ Sustain 29:14–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2017.10.004

Milton SJ, Esler KJ, Dean WRJ (2006) Karoo veld ecology and management. Briza Press, Pretoria

Moran VC, Hoffmann JH, Zimmermann HG (2013) 100 years of biological control of invasive alien plants in South Africa: history, practice and achievements. S Afr J Sci 109:Art. #a0022, 6 pages. https://doi.org/10.1590/sajs.2013/a0022

Ntshotsho P, Prozesky HE, Esler KJ et al (2015) What drives the use of scientific evidence in decision making? The case of the South African Working for Water program. Biol Conserv 184:136–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2015.01.021

Roux DJ, Rogers KH, Biggs HC et al (2006) Bridging the science-management divide: moving from unidirectional knowledge transfer to knowledge interfacing and sharing. Ecol Soc 11:4. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-01643-110104

Roux DJ, Kingsford RT, Cook CN et al (2019) The case for embedding researchers in conservation agencies. Conserv Biol 12(1):133–143. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.13324

Scholes RJ, Anderson F, Kenyon C et al (2008) Science councils in South Africa. S Afr J Sci 104:435–438. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0038-23532008000600014

Shaw JD, Wilson JRU, Richardson DM (2010) Initiating dialogue between scientists and managers of biological invasions. Biol Invasions 12:4077–4083. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-010-9821-9

Shine R (2018) Cane toad wars. University of California Press, Oakland. https://doi.org/10.1525/9780520967984

van Wilgen BW (2020) A brief, selective history of researchers and research initiatives related to biological invasions in South Africa. In: van Wilgen BW, Measey J, Richardson DM, Wilson JR, Zengeya TA (eds) Biological invasions in South Africa. Springer, Berlin, pp 31–64. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-32394-3_2

van Wilgen BW, De Lange WJ (2011) The costs and benefits of invasive alien plant biological control in South Africa. Afr Entomol 19:504–514. https://doi.org/10.4001/003.019.0228

van Wilgen BW, Wannenburgh A (2016) Co-facilitating invasive species control, water conservation and poverty relief: achievements and challenges in South Africa’s Working for Water programme. Curr Opin Environ Sustain 19:7–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2015.08.012

van Wilgen BW, Wilson JRU (eds) (2018) The status of biological invasions and their management in South Africa in 2017. South African National Biodiversity Institute, Kirstenbosch and DST-NRF Centre of Excellence for Invasion Biology, Stellenbosch

van Wilgen BW, Little PR, Chapman RA et al (1997) The sustainable development of water resources: history, financial costs and benefits of alien plant control programmes. S Afr J Sci 93:404–411

van Wilgen BW, Davies SJ, Richardson DM (2014) Invasion science for society: a decade of contributions from the Centre for Invasion Biology. S Afr J Sci 110:Art. #a0074, 12 pages. doi: https://doi.org/10.1590/sajs.2014/a0074

van Wilgen BW, Boshoff N, Smit IPJ et al (2016a) A bibliometric analysis to illustrate the role of an embedded research capability in South African National Parks. Scientometrics 107:185–212. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-016-1879-4

van Wilgen BW, Fill JM, Baard J et al (2016b) Historical costs and projected future scenarios for the management of invasive alien plants in protected areas in the Cape Floristic Region. Biol Conserv 200:168–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2016.06.008

van Wilgen BW, Carruthers J, Cowling RM et al (2016c) Ecological research and conservation management in the Cape Floristic Region between 1945 and 2015: history, current understanding and future challenges. Trans Royal Soc S Afr 71:207–304. https://doi.org/10.1080/0035919X.2016.1225607

van Wilgen BW, Wilson JR, Wannenburgh A et al (2020) The extent and effectiveness of alien plant control projects in South Africa. In: van Wilgen BW, Measey J, Richardson DM et al (eds) Biological invasions in South Africa. Springer, Berlin, pp 593–624. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-32394-3_21

Visser V, Wilson JRU, Canavan K et al (2017) Grasses as invasive plants in South Africa revisited: Patterns, pathways and management. Bothalia 47(2):a12169. https://doi.org/10.4102/abc.v47i2.2169

Wicht CL (1945) Report of the Committee on the Preservation of the Vegetation of the South Western Cape. Cape Town, Royal Society of South Africa

Wilson JRU, Gaertner M, Richardson DM et al (2017) Contributions to the national status report on biological invasions in South Africa. Bothalia 47(2):a2207. https://doi.org/10.4102/abc.v47i2.2207

Wilson JRU, Faulkner KT, Rahlao SJ et al (2018) Indicators for monitoring biological invasions at a national level. J Appl Ecol 55:2612–2620. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.13251

Zachariades C, Paterson ID, Strathie LW et al (2017) Assessing the status of biological control as a management tool for suppression of invasive alien plants in South Africa. Bothalia 47(2):a2142. https://doi.org/10.4102/abc.v47i2.2142

Acknowledgements

LCF acknowledges South African National Parks, the Centre of Excellence for Invasion Biology, Stellenbosch University, and the National Research Foundation of South Africa (Grant Numbers IFR2010041400019 and IFR160215158271). KJE and BvW thank the Centre for Invasion Biology and the South African National Research Foundation (Grant 109467 to BvW and Grant 103841 to KJE) for support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2020 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Foxcroft, L.C., van Wilgen, B.W., Abrahams, B., Esler, K.J., Wannenburgh, A. (2020). Knowing-Doing Continuum or Knowing-Doing Gap? Information Flow Between Researchers and Managers of Biological Invasions in South Africa. In: van Wilgen, B., Measey, J., Richardson, D., Wilson, J., Zengeya, T. (eds) Biological Invasions in South Africa. Invading Nature - Springer Series in Invasion Ecology, vol 14. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-32394-3_28

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-32394-3_28

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-32393-6

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-32394-3

eBook Packages: Biomedical and Life SciencesBiomedical and Life Sciences (R0)