Abstract

Our changing relationship with the biosphere is one of many anxieties that human society currently confronts. The paradox that some biodiversity that has been moved across the planet by human trade could actually be harmful is unknown to many people. They are either oblivious, or perceive nature as being under threat, rather than as threatening in itself. Consequently workers in the field of invasion science widely acknowledge the need to inform the public about the subtleties surrounding the movement and control of invasive alien species, where some biodiversity can be bad or good, depending on our immediate relationship with those particular organisms. The aspects of South African science and environmental education reviewed for this chapter reveal broad-scale efforts to explain the impacts and intricacies of invasive species; these range from inclusion in school and university curricula, through to exposure on primetime television. Nevertheless, other surveys show that many people remain unaware of the issues around invasive species. Several South African awareness projects reviewed in this chapter conclude that more needs to be done, including further assessment of people’s knowledge of and attitudes to invaders. Use of citizen science, as a mechanism for both data collection and creation of awareness about invasive species, is proposed as a mechanism to personalise those species that directly impact our individual lives, where, for example, they compete with us for ecosystem services or sicken us through allergies.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The impacts of invasive alien organisms in their new habitats are well known to ecologists and are covered elsewhere in this book (Le Maitre et al. 2020, Chap. 15; O’Conner and van Wilgen 2020, Chap. 16; Zengeya et al. 2020, Chap. 17). However, given the diversity of exposure of ordinary people to invasive alien species (invasive species), the societal impacts of such organisms vary, depending on the species and the scale at which they are experienced (De Wit et al. 2001; Shackleton et al. 2017). Consequently public perceptions range from ignorance, through indifference, to rage. Across the globe, researchers and conservationists involved in invasion biology often call for increased awareness of these threats and the control mechanisms that are available to manage them (e.g. Novoa et al. 2018; Shackleton et al. 2020, Chap. 24). Therefore, promoting a broad public understanding of invasive species should be among the wider goals of conservationists, researchers and ecosystem managers.

Because the negative impacts of many invasive species outweigh their positive effects, they need to be managed (Le Maitre et al. 2002; van Wilgen et al. 2004). In South Africa, control is obligatory for alien species listed in terms of regulations under the National Environmental Management Biodiversity Act (NEM:BA) . In the case of invasive plants, this control takes the form of mechanical removal, treatment with herbicides, or biological control using natural enemies to reduce the extent and spread of the invasive plant (van Wilgen 2018; van Wilgen et al. 2020; Hill et al. 2020a, Chap. 19); alternative methods are employed for the control of invasive animals (Davies et al. 2020, Chap. 22). These efforts are predominantly funded by the Department of Envrionment, Forestry and Fisheries (DEFF) , and coordinated by the National Resource Management Programme under the Working for Water (WfW ) banner (van Wilgen et al. 2012). WfW is one of the government’s largest public works programmes, which has created more than 20,000 jobs per year over two decades, and it is important that the South African public know about and understand the economic and biodiversity issues which surround alien species entering and residing in their country (Le Maitre et al. 2002). Citizens should also be aware of efforts being made to control such species, and what role they can potentially play in either restricting their entry or in efforts to manage them.

The management of invasive species should ideally involve public engagement to minimise social conflict (Estévez et al. 2015 ). The basis of such engagement should be inclusive, drawing in all segments of the population. Bremner and Park (2007) note that public support likely to be generated by such engagement is critical for the success of invasive species management programmes, because without buy-in from affected communities, such initiatives are difficult to coordinate. Engaging with the public, garnering political support, often because of job creation, along with robust scientific evidence, can support success in the control of invasive species, as seen in the clearing of alien trees from Table Mountain National Park (van Wilgen 2012).

Frequently, adequate public engagement and participation does not take place due to the lack of funding, or of time or inclination on the part of researchers or implementing agents (Novoa et al. 2017; Shackleton et al. 2020). Nevertheless, education and awareness-raising of invasive species can take many forms, from inclusion in the national school curriculum , through to inserts in wildlife television shows. This chapter presents a summary of South African efforts to promote awareness about invasive species, their impacts and their management, through both formal education routes and broader, more informal outreach efforts. Because education and training are inextricably linked to capacity-building of skills in the workplace, such efforts linked to invasive organisms are also reviewed. The authors surveyed educational literature and colleagues in both education and research for evidence of outreach activities linked to invasive organisms.

The overall conclusion reached is that South Africans are exposed to a broad swath of information on invasive organisms, especially alien plants, as exemplified by President Ramaphosa’s eulogy for the late Minister of Environmental Affairs, Edna Molewa, on 6 October 2018, in which he spent several minutes extolling the successes of the Working for Water Programme and mentioned that the Minister had requested to be buried in an “eco-coffin”, made from the wood of alien trees. Nevertheless, no formal assessments of public awareness and understanding of the issues surrounding the impacts of alien species have been conducted, and the status of the topic in the school curriculum appears tenuous.

2 Invasive Organisms in the South African School Curriculum

South Africa’s political history, as with so many aspects of the country, has influenced the manner in which the subject of life-sciences, and alien species in particular, feature in the school curriculum. When elected in 1948, the Nationalist government introduced Christian National Education in response to perceived oppression by the British. This persisted in one form or another until replaced by the post-apartheid government, which instituted the Revised National Curriculum in 2005. This was reviewed in 2006 as the Revised National Curriculum Statement, and again in 2013, to become the Curriculum and Assessment Policy, which currently stands as the national curriculum in state schools (Sanders 2018). This history is pertinent to the issues of the teaching of any subject in South Africa because curriculum changes place demands on teachers (Ball and Cohen 1996). This can undermine their confidence and knowledge in a subject, particularly one that requires specialist knowledge such as identifying alien species and explaining their impacts. Nevertheless, these changes in curriculum allowed for invasive species and biological control to be introduced in the national curriculum. Content on invasive species and their control was introduced into the final high school year (Grade 12) Life Sciences curriculum in 2007, but was rapidly shifted to the preceding year’s curriculum (Grade 11) in 2009 (e.g. Clitheroe et al. 2007, 2009) where the topic still persists, but with a questionable impact on ~300,000 learners (the South African term for pupils or students in formal education from age 6 to 18) who study Life Sciences each year.

Each year, South Africa has approximately 12 million pupils in the state school system, with a further half a million in independent schools. There are ~425,000 teachers in 25,720 schools. Schooling is broken into four phases, with each year group being a “grade” (children begin primary school at age 6 and complete this phase at age 13). High school starts at Grade 8 (children turn 14 during Grade 8) and finishes in Grade 12 (“matric”, aged 18). Life Sciences is the most popular optional subject taken in those last 3 years of school, attracting 53% of pupils who write the matric examinations (Sanders 2018) and is selected ahead of History, Geography, French, Music or Accountancy.

In Grade 10, Life Sciences pupils around the age of 16 years are introduced to the concept of biodiversity and its importance, including an overview of factors that influence biodiversity in biomes. Invasion science is not covered as a separate theme, but is part of a larger unit dealing with the impacts of human activity on the environment. However, the concept is briefly introduced as an example of a threat to biodiversity. A unit on practical fieldwork, requiring pupils and teachers to design and implement a field investigation over two school terms is included. This could potentially be a survey of alien species such as ants (Davies et al. 2016), close to the school.

In Grade 11, the focus is on the impact of human activity on the environment. Here pupils and teachers delve deeper into invasive species and their associated impacts on local biodiversity and natural resources. Examples from curriculum guides and current textbooks mainly discuss invasive plants and their impacts on the quality and quantity of freshwater resources, the reduction of agricultural land and local biodiversity and its loss. The accompanying textbooks also touch briefly on the different ways in which invasive plants are controlled.

The concept of invasive species is further developed in the Grade 11 curriculum document under the topic ‘Human Impact on the Environment: Current Crises for Human Survival: Problems to be Solved within the Next Generation’ (Department of Basic Education 2011). Reference to ‘exotic plantations and depletion of water table’ is made within the water availability section. In the food security and loss of biodiversity sections, ‘alien plants and the reduction of agricultural land’ and ‘alien plant invasions: control using mechanical, chemical and biological methods’ are mentioned. In the Curriculum and Assessment Policy, it states that a practical observation of one example of a human influence on the environment should take place in the pupil’s local area, and a report should be written from the chosen example. The example given is a suggestion to observe the impact of alien species on local biodiversity. This is promising, as teachers may use this to explain the task and some pupils may choose this topic. However, impacts of invasive species should be observed over a long time, which makes it difficult to run as a project in two school terms, unless the project is just a biodiversity assessment. In addition, the fairly high level of knowledge about local invasive species and general biodiversity that is required by the teacher to guide pupils in this exercise might be lacking (Le Grange 2010). Invasive species do not appear in the Grade 12 syllabus, and consequently the subject is not carried through for examination in the final matric exams, which reduces its impact within the curriculum.

Engagement by two authors of this chapter (KNW and MJB, independently) with Life Science teachers (Grades 10, 11 and 12) from both private and government schools, revealed that most do cover invasive species in their classroom. Others would like to cover this topic in their lessons but lack specific information for good lesson plans, reinforcing the suspicion that many teachers lack the specialist knowledge to teach about invasive species and their control (Le Grange 2010), despite almost certainly living near environments that are invaded. Efforts to distribute lesson plans by one of us (MJB) at provincial and national teacher’s conferences were met with great enthusiasm from teachers who took digital copies of lesson plans, invasive plant portfolios and Henderson’s (2001) invasive plant identification guide. However, follow-up from those teachers was minimal, suggesting that teachers are extremely busy or that some may lack the confidence to implement environmental education programmes (Le Grange et al. 2012).

A search of the final matric examination papers from 2013 to 2017, consisting of a total of 20 papers (November final and February supplementary sittings), revealed not a single mention of the following words: invasion; invasive; alien; biological control; biocontrol. Invasive species are in the school curriculum but lack the emphasis that many workers in the field feel they deserve. This has several possible causes. Firstly, they are no longer in the Grade 12 syllabus and are therefore not examined in the final matric examinations. Coverage of invasive organisms in school textbooks, produced by independent publishers, is variable and may contain “latent errors” (Sanders and Makotsa 2016), where separation of related content causes confusion, or is simply incorrect. One such textbook, in describing the release of biological control agents against invasive plants, states that “The species chosen for release is not always an indigenous species, increasing the possibility of even more invasive species” (Isaac 2012). Given that South Africa has a 100 year history of biological control of alien weeds (Zimmermann et al. 2004; Hill et al. 2020a, Chap. 19) without a single example of an agent exhibiting unexpected non-target impacts on other species, this type of hyperbole undermines modern biocontrol. A few examples of non-target impacts of biological control agents are known from other countries, but these also are generally overstated (Blossey et al. 2018). However, a local textbook from a different publisher has two pages of accurate descriptions of alien plants, their means of introduction and effects on ecosystems and biodiversity. It correctly explains control methods, including biological control, covers the effects of invasive alien plants on water resources, and mentions the WfW programme (Webb et al. 2012).

Textbooks inevitably guide teachers’ interpretations of the curriculum (Sanders and Makotsa 2016), especially in a system where the curriculum is changed with such regularity. The ideal curriculum is formulated into a policy document, which becomes the formal curriculum. This is turned into a perceived curriculum by the authors of school textbooks, and interpreted into the enacted curriculum by the teachers (Le Grange 2008). Curriculum slippages (Ball and Cohen 1996) can occur at each stage, as seen in the biological control example above, reducing the impact and accuracy of information on a topic. If invasion science is to attain a higher profile in the South African school curriculum , then invasion biologists need to become involved in the production of the school textbooks. Simply including information about invasive species in the curriculum will not necessarily create awareness or lead to a change in attitudes (Le Grange 2008). However, if researchers in invasion biology become involved in the development of these materials and provide information directly to teachers, using less structured curricula that weaken the boundaries between classrooms and communities (Le Grange et al. 2012), then schools can be the ideal starting point for improving awareness of biological invasions. Several researchers and their institutions have shared their resources in such outreach programmes (Le Grange and Ontong 2018). The following section presents an example of a successful school intervention run from the DSI-NRF Centre of Excellence for Invasion Biology (C·I·B) hub at Stellenbosch University.

2.1 The Iimbovane Outreach Project: Exploring South African Biodiversity and Change

In 2006, the C·I·B initiated an educational project, the Iimbovane Outreach Project, to support both teachers and pupils in biodiversity and invasion science . Iimbovane (which means “ants” in isiXhosa, 1 of South Africa’s 11 official languages) uses ants as a basis for teaching biodiversity and invasion science to teachers and pupils at the high school level. The project takes an experiential learning approach, where pupils and teachers are directly involved in the creation of knowledge through the collection of ants and environmental data in different biomes of the Western Cape . The project is currently implemented in 18 Western Cape schools and engages approximately 1200 pupils annually. Project activities include classroom lessons and field investigations in the school grounds and in nearby protected areas . Fieldwork uses simple pitfall trapping to collect ants. Participating pupils and teachers discover a diversity of ant groups, while classroom lessons use microscopes and scientific keys to identify the ant species.

Ants are an ideal group to use because all school grounds are teeming with many species, allowing explanations of biodiversity indices such as species richness. Ants are easy to collect and fairly straightforward to identify, albeit with the aid of a microscope in some cases. The protocol can be easily repeated should pupils or teachers want to use it as a monitoring project as required for the Life Sciences curriculum.

The discovery of the invasive Argentine Ant (Linepithema humile) in the pupil’s sampling efforts encourages discussion about invasive species. Using the Argentine Ant as an example, the project helps pupils understand how invasive species compete with native species and influence ecological interactions, for example the interaction between ants and native plants that depend on native ants for seed dispersal . The theme of invasive species is further explored during the project’s school holiday programmes. During these programmes, pupils conduct their own field investigations on invasive species and their impact on the diversity of local ecosystems.

The main benefit of the Iimbovane Outreach Project lies in its contribution to educating both pupils and teachers at the high school level about biodiversity and invasion science. The three specific aims of the Life Sciences curriculum include knowing Life Sciences, doing Life Sciences and understanding the applications of Life Sciences in everyday life. Teachers in turn benefit from the project through training workshops and educational materials produced at these workshops. The Iimbovane manual, classroom worksheets and assessment activities are co-developed by participating teachers, the Western Cape Education Department curriculum advisors, and the C·I·B project team to ensure that the materials are in line with curriculum requirements and useful to teachers in a formal classroom setting.

Another important aim of the programme is to inspire and encourage pupils to follow careers in the sciences. To date 267 pupils from Iimbovane partnership schools have enrolled for degrees in the sciences (2009–2015) (Table 25.1). This could partly be as a result of their exposure to Iimbovane in Grade 10, but cannot be attributed to the project alone. One Iimbovane participant decided to study a BSc in Biological Sciences because of her exposure to Iimbovane, which she described as follows:

My first experience of real science was during our school’s involvement with the Iimbovane Project. The project showed me as a Grade 10 learner what science is about, from working outside in the field, doing laboratory work and microscope work and how to explain one’s findings. The Iimbovane Project played a part in my choice for tertiary studies. I always knew that I wanted to study further after school, but I was not familiar with the different courses offered. Being based at Stellenbosch University during one of the Iimbovane Project workshops, I was exposed to the university and what it offers. It made me feel self-assured about coming to Stellenbosch University.

2.2 Eco-schools

The Wildlife and Environment Society of South Africa (WESSA) runs an Eco-Schools Programme that has enrolled more than 4500 schools across South Africa since 2003, reaching 640,000 pupils and 4264 teachers (Dzerefos 2018). It is a long-standing initiative where schools join and use a seven-step framework to implement eco-projects. The framework takes schools through the process of choosing, planning and implementing a project by forming an eco-committee at the school, which involves all stakeholders. There are various themes for these projects of which the Biodiversity and Nature theme has elements of invasive species within it. Participating schools choose to focus on removing invasive alien plants and replacing them with native plants as an expression of this theme. Through this process they learn and understand what invasive species are and how they impact our environment. However, in a recent survey of attitudes to environmental issues and sustainability, pupils from South African Eco-Schools scored no differently to their peers from non-Eco-Schools, although both scored fairly well compared with other nationalities (Nair 2018). Schools join the WESSA Eco-Schools Programme by registering through WESSA who over the last few years have had between 565 and 853 schools registered as part of the programme.

3 Biological Invasions and Biological Control Studies at Tertiary Level in South Africa

South Africa has 12 traditional universities, 6 comprehensive universities (which offer a combination of academic and vocational diplomas and degrees), and 9 universities of technology (focusing on vocational qualifications). A review of online content of science prospectuses and web-based content advertising courses for these universities showed that the majority of traditional and comprehensive universities offer some training in either invasive species or biological control or both subjects. The universities of technology were not covered by this survey.

Lack of information on course content advertised on university web pages does not necessarily mean that courses on biological invasions or biological control are unavailable. For example, the University of KwaZulu-Natal does not have the subject of biological invasions or related content in course outlines but it has leading researchers in the fields of biological control and biological invasions who bring such expertise to their teaching and research programmes.

Course convenors and researchers were invited to take part in an online survey to give an indication of course content on invasive species and biological control. Forty-four researchers and lecturers affiliated to 19 universities were invited to submit information, of which 9 individuals from 7 universities responded to this request. These seven universities have a significant focus on invasive species and biological control. They are: the University of Cape Town; University of KwaZulu-Natal ; University of Pretoria ; University of the Western Cape; University of the Witwatersrand; Rhodes University; and Stellenbosch University.

All seven of these universities cover the topic of invasive species at an undergraduate level. The C·I·B, with its hub at Stellenbosch University but with affiliations to numerous South African universities, facilitates training of students in the field of biological invasions beyond Stellenbosch University itself. A chapter on the C·I·B and its activities appears elsewhere in this volume (Richardson et al. 2020, Chap. 30).

The topic of biological control is not covered by the University of the Western Cape at any stage, while Stellenbosch University and the Universities of Cape Town and Witwatersrand offer this topic at undergraduate level, University of KwaZulu-Natal only offers the subject at postgraduate level and Rhodes University offers courses at both undergraduate and postgraduate levels. The Centre for Biological Control (CBC), based at Rhodes University , is a consortium of four universities (Cape Town, KwaZulu-Natal , Witwatersrand, and Rhodes). It undertakes both undergraduate and postgraduate training, research and implementation of biological control on invasive plants and certain agricultural invertebrate pests, therefore this consortium understandably does the majority of training in this field.

Among the students that take courses in the departments surveyed, there is generally a high level of interest for the subject of invasive alien species and their control. The fact that South Africa is a world leader in the field of biological control heightens the significance for students, as does the more “applied management” side of biological control research.

Numerous postgraduate degrees have been awarded between 2007 and 2017 to students who have trained in biological control or invasion biology in the departments that responded. The University of the Witwatersrand estimates that they have had more than 35 honours graduates and Rhodes University reports up to 40 at this level. At a Masters level 91, and at PhD level 46 graduates, were awarded degrees over the same decade (this figure excludes C·I·B and University of Cape Town graduates). The majority of these postgraduate students receive a bursary, from a variety of sources, to undertake their studies in this particular field. Three examples are given below, which show how invasive species pervade the university curriculum at many levels.

At least 12 lecturers from the School of Animal, Plant and Environmental Sciences at the University of the Witwatersrand discuss some aspect of invasive species in 13 courses, ranging from first year Introductory Life Sciences to a coursework MSc in Conserving Biodiversity. Research is also conducted on invasive species at Honours through to Post-Doctoral level. Some courses such as Foundations of Ecology (second year) and Functional Ecology (third year) use invasive species as recurring themes and threads throughout the course, while they are included in Aquatic Ecology (second year), Biotic Diversity (second year), Pollination Biology (fourth year) and Biogeography (fourth year). Invasive species and biological control occupy at least half of the Medical and Applied Entomology course (third year), while the Honours Biocontrol course (fourth year) is centred on invasion biology and invasive plants in particular. Consequently, graduates of the School of Animal, Plant and Environmental Sciences (~80 year−1) will have encountered invasive species at several points in their university career, with many of them having studied invasive plants in some detail, or even completed and published research on the topic.

At the University of Pretoria , invasive species are covered in four second- or third-year modules and in two Honours modules, but no courses or modules are explicitly devoted to invasion biology. Biological control is also covered in two of those undergraduate courses. At the postgraduate level, five academic staff supervise projects involving invasive species, and one Post-Doctoral fellow. The associated Forestry and Agricultural Biotechnology Institute (FABI) on the same campus supports extensive postgraduate research involving invasive organisms and their biological control.

The Biodiversity and Ecology programme at the Department of Botany and Zoology at Stellenbosch University has included a third-year option in Invasion Ecology since 2014. The course trains more than 50 students per year and comprehensively covers topics concerned with biological invasions including the processes governing their success, their impacts and management. The course is led by members of the C·I·B Core Team based in the Department of Botany and Zoology, and features guest lectures by adjunct staff in areas of their specialities. Practicals have an experimental base in which students design controlled experiments, normally on invasive plants.

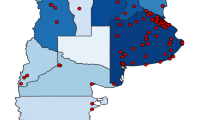

Over its 15 years of existence, the C·I·B has produced invasion scientists, not just for South Africa, but for the world (van Wilgen et al. 2014; Richardson et al. 2020, Chap. 30). The C·I·B has to date hosted 340 postgraduates, comprising 103 MSc students and 2 MAs, 57 doctoral students and 63 post-doctoral researchers (Fig. 25.1; Richardson et al. 2020, Chap. 30). The capacity-building has a clear bias toward South Africa, where 75% of C·I·B alumni are now employed. However, there has been considerable movement of C·I·B alumni to developed countries in Europe, Australia and North America (15%), as well as a flow of people into BRICS nations (2%) and the SADC region (2%). A third of C·I·B alumni occupy academic posts at universities and another 14% are studying towards higher degrees. Government and implementation bodies have been major employers, employing 18% of the graduating capacity. Another 16% have moved into private companies (often involved in conservation work), and 6% into the non-governmental sector.

Global distribution of 156 alumni of the DSI-NRF Centre of Excellence for Invasion Biology (C·I·B) [current positions of 20 are unknown] with their distribution in southern Africa (inset). Coloured symbols represent the post-graduate capacity emanating from the C·I·B: Post-doctoral fellows = green stars; PhD = red; MSc = yellow; Honours = purple

The obvious value of postgraduates emerging from the C·I·B, CBC, and other university programmes underscores the need to grow capacity in this area and in associated disciplines such as economics, public relations and mathematics. In addition, biosecurity could be strengthened if enforcement and compliance personnel had formal training in the field. Invasive species management also impinges on history, sociology, law and land management, all of which are under scrutiny and change within the new democracy of South Africa. Trans-disciplinary approaches are needed to include geography, health and safety and supply chain management. The South African government has stated its objective to expand such skills in the environmental sector (Giordano et al. 2012).

4 Non-degree Training

The accredited “Weed Biological Control Short Course” at Rhodes University has run 21 times since 2005, growing from an initial 10 participants per course to a maximum of 25 each year (Weaver et al. 2017; Martin et al. 2018). The practical application of biological control of invasive plants is presented against a background of ecological theory, legal regulations and monitoring . The safety of biological control based on host specificity testing is emphasised. Practical seminars on data analysis and basic statistics accompany fieldwork exercises. Participants submit a written report that is graded to assess competency before being awarded a certificate. The course attracts staff from South African National parks, land managers, WfW implementation officers, postgraduates in applied entomology and botany, and even concerned members of the public. About 10% of recent participants have come from other African countries, being mostly university lecturers or students (Martin et al. 2018).

5 Awareness-Raising Beyond Formal Education

In addition to the Iimbovane Outreach Project at the C·I·B, which is specifically aligned to the national high school curriculum , some university departments take their research expertise in invasive species, mainly as biological control displays, to annual exhibitions such as Sci-Fest Africa and National Science Week. Two examples are described below.

Yebo Gogga started as an interactive arthropod exhibition in 1996 (Crump et al. 2000), originally held at the Johannesburg Zoo, moving to the University of the Witwatersrand in 2004. The title is a hybrid of “yes!” or “hallo” in Zulu, combined with the Afrikaans vernacular for an insect, “gogga”, itself derived from the Khoikhoi “xo-xon”, a collective term for creepy-crawlies. The exhibition always includes examples of insects used for biological control of invasive plants. Other NEM:BA listed organisms along with invasive insects have occasionally featured. The show is successful because the exhibits are run by the University of the Witwatersrand’s students, which allows visitors to interact directly with the material on display and ask questions of an informed presenter, who is usually a postgraduate doing research related to the exhibit. This direct student involvement gives visitors a hands-on experience of each topic, which would otherwise be potentially unappealing without a knowledgeable expert on hand to add anecdotes, and most importantly, enthusiasm to the experience. School teachers are provided with booklets or online exercises that they can use to incorporate the visit to Yebo Gogga into the larger school curriculum , from Grades 0 to 12.

The original shows at the zoo attracted up to 12,500 visitors per year, probably because people incorporated the exhibition into their zoo trip (Crump et al. 2000). Publicity for these shows was also impressive, with more than a dozen print articles, one or two radio slots and television appearances per year, ensuring that the show in general, even if not the invasive themes specifically, was being exposed to the public. Moving to the the University of the Witwatersrand has dropped visitor numbers to an average of 5000 per year. However, the show is now more specifically targeted at schools that receive formal invitations from the University. On average 2500 pupils visit each year accompanied by about 150 teachers from 35 local schools. Age groups from nursery school to university and beyond are accommodated by the expert exhibitor, who can tailor their presentation to the knowledge of the individuals they are addressing. The participating postgraduates enjoy the chance to show off their knowledge and research to the public. It is an affirmation for them that their otherwise esoteric and academic knowledge has value both for the public good and for themselves when they enter the job market. This conclusion is supported by the number of volunteers who return every year during the course of their studies towards degrees in Life Sciences.

The exhibition usually features in local radio magazine programmes each year and has been covered by the 50/50 TV show (see below) on more than one occasion. The biological control exhibits have also appeared at the National Science Week, which is hosted annually by the University of the Witwatersrand.

Sci-Fest Africa is an annual science festival that has been staged in Makhanda (Grahamstown) since 1996 (Martin et al. 2018). Sci-Fest Africa is a week-long science festival, primarily aimed at school children, where science is presented to the South African education community in an interactive format (http://www.scifest.org.za/). The festival showcases local and international organisations and attracts more than 50,000 visitors annually from across South Africa (Sci-Fest Africa 2019). The Rhodes University CBC has participated since 2013, offering an interactive exhibition involving postgraduate students interacting with pupils, teachers and the general public about invasive species, the biological control of invasive plants and the ecological consequences of such plants (Weaver et al. 2017). The exhibition allows pupils to see and touch invasive plants and their biocontrol agents, with additional visual material such as before and after photos of biological control successes. An average of 6000 people (mostly pupils) pass through the exhibition over the course of the week.

Both exhibitions are novel in that they reveal how small insects can be used as biological control agents (Crump et al. 2000; Martin et al. 2018). This approach can benefit both the pupil and teacher when guided by an expert in the field (Weeks 2015).

6 Invasive Alien Species on South African Television

50/50 is South Africa’s best-known wildlife and conservation television show (http://www.5050.co.za). It has been aired by the South African Broadcasting Corporation since 1987, making it one of the longest-running programmes produced by the national broadcaster. It is a very popular programme watched by approximately 1.2 million South Africans every week, which may well be one of the reasons it has survived the political transitions that have taken place in South African broadcasting since 1994. Its name indicates the show’s original philosophy, to balance human topics with stories from nature, consequently environmental issues are a regular feature of the broadcast. It is presented in a magazine-type format and airs about 40 episodes per year.

Content schedules for 50/50 from April 2010 to August 2018 indicate that invasive species are discussed roughly once a year. The topics ranged from alien trout and other invasive fish to invasive insects, such as the Fall Army Worm (Spodoptera frugiperda), invasive plants, and the people who are involved in their control in South Africa. In comparison, rhino conservation garners about four news slots per year. The programme is a well-respected vehicle for disseminating environmental information to a largely self-selected group. Nevertheless, over the years 50/50 has highlighted successes in the biological control of invasive aquatic invasive plants such as Red Water Fern (genus Azolla) and Water Hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes), and historical and more recent achievements against invasive cacti (Family Cactaceae).

7 Communication and Advocacy on Invasive Alien Species by the South African Government

In 2000, the Working for Water (WfW ) programme formalised efforts to raise awareness about the threats of invasive plants, through a ‘Weed Buster Week’ (Magadlela and Mdzeke 2004), targeting specific invasive plants in different areas of the country, visiting schools, often with involvement from a ministerial level. This event continues on the country’s annual awareness event calendar, along with Arbor Week and Water Week, both of which include invasive plants as part of their educational content. Horticultural nurseries, parks and municipalities are also targeted, which resulted in a partnership with the South African Nursery Association (SANA), to encourage nurseries not to sell invasive plants. Event-focussed campaigns, for example preventing the spread of the aquatic invasive plant Hydrilla (Hydrilla verticillata) from Jozini Dam, aimed at boat owners attending the Tigerfish Bonanza (Coetzee et al. 2009), opportunistically publicise the hazards of invasive species (Hill et al. 2020b, Chap. 4).

Communication and advocacy efforts around invasive species in South Africa grew from these beginnings and were, until recently, funded by government through the Environmental Programmes of the (DEFF) . A great deal was accomplished because of this financial support and the energy of an invasive species advocacy champion. The WfW awareness programme arose from partnerships that WfW had with both the forestry and green industries, and allowed the DEFF to develop their relationships with the South African Nursery Association, and the South African Landscape Institute, the South African Green Industries Council and the country’s gardening media, to raise awareness of the threat of invasive species.

When the 2014 NEM:BA legislation was passed, the then Department of Environmental Affairs (DEA) linked their advocacy campaign to a job creation programme, managed by the South African National Biodiversity Institute (SANBI) . Known as the Groen Sebenza (Green Worker) programme, 21 biosecurity interns were allocated to a 2-year training period (2014–2016). The programme set about raising awareness through various publicity campaigns, training programmes and stakeholder meetings. Marketing materials on invasive species were created and distributed by this group, primarily funded by DEA . Most of this advocacy information, including a huge array of articles, posters, banners, booklets and pamphlets, is still available on the invasives.org website for download by anyone interested in raising awareness about invasive species, or pupils and communities needing invasive species information. The topics cover identification and impacts of invasive species in articles appearing in gardening magazines and similar publications. Value-added industry programmes such as eco-furniture are also described. Alien wood is turned into eco-furniture such as school desks and low-cost coffins, like the one requested by the late Minister of Environmental Affairs in advance of her own funeral in 2018.

The 2014 NEM:BA Alien & Invasive Species Regulations required that people selling property must notify the purchaser of the presence of any NEM:BA listed invasive species on that property, in a “Declaration of Invasive Species document”. This stimulated the SANBI advocacy unit to partner with South African Green Industries Council to offer training on invasive species for people interested becoming consultants in “green industries”. These courses attracted over 2400 people, who paid to be trained as “Invasive Species Consultants”. Municipalities sent their horticulturists and landscapers, while large state-owned enterprises such as Transnet (freight) and Eskom (electricity) sent managers and environmental practitioners. Trainees from all walks of life attended modules which lasted from 1 to 4 days, in which they learnt about identification and the legislation concerning invasive species; management of declaration documents, permits and control plans, followed by herbicide use in theory and finally in practice. Training was conducted in 10 major cities between 2015 and 2018.

Nine invasive species stakeholder meetings were held, one in each province, during 2015, sponsored by the DEA advocacy unit, with the objective of explaining the new NEM:BA legislation to government officials, private businesses and charitable foundations working in the sectors of agriculture, conservation, and the green industries. More than 3500 people attended these meetings. In addition, the unit contributed to other regional advocacy meetings such as the CAPE Invasive Alien Animal Working Group (CAPE IAAWG), the KwaZulu-Natal Invasive Species Forum, the Famine Weed Advocacy and Education Meeting, and the National Cactus Working Group . Each of these involved researchers and government officials who continue to meet several times a year at different affected localities around South Africa to discuss invasive species control.

Other forms of communication have included recording almost a hundred videos of scientific presentations at local conferences, such as The Annual Research Symposium on the Management of Biological Invasions in Southern Africa. Many of these videos have had up to 10,000 views suggesting that they have great potential to spread useful information to a self-selected audience. These videos are available at Invasive Species South Africa (ISSA).

With over 535 invasive species gazetted in the 2014 NEM:BA lists, the Groen Sebenza interns researched and distributed packages of information on invasive species via three Facebook pages on invasive species from 2012 to 2018. A new package, consisting of four relevant pictures, accompanied by three paragraphs of text, on a new invasive species was posted a minimum of twice a week on all three pages. These pages are known and well regarded by researchers in the field. The three pages have respectively 8230; 2686 and 281 followers and can be found at ISSA.

DEA sponsorship of invasive species advocacy and awareness leading up to and after the passing of the NEM:BA regulations was critical for South Africans to understand and embrace (to some extent) the regulations. Moreover, it led the way for a ripple effect among many other government and non-governmental organisations, which have gone on to fund awareness initiatives within their own organisations. Importantly, the need to measure the impact of such advocacy programmes should be built in to any future proposals of this nature.

8 Other Government Initiatives

Besides direct support of awareness programmes on invasive aliens, the South African government has been indirectly responsible for many other awareness efforts carried out by its agencies that are involved in research on alien species or biological control of alien plants. The summarised account below is unlikely to be comprehensive due to the dispersed nature of such information, which is often targeted at a limited group of specialist consumers.

Plant Protection News is an on online-only publication that appears twice a year. It is distributed to members of the Plant Protection Research Institute (PPRI) and other interested parties who subscribe to the newsletter. The PPRI is part of the public entity and principal agricultural research institution in South Africa known as the Agricultural Research Council (ARC). The document is substantial, usually being around a dozen pages that cover many topics of interest to its self-selected audience and always has several articles on invasive alien plants, or invasive insects of agricultural importance. The newsletter of Southern African Plant Invaders Atlas, SAPIA News, is a similar publication that has appeared since 2006. Other SAPIA publications include a series of leaflets on invasive plants, fact sheets for the ARC and for AGIS-WIP (Agricultural Geographical Information System-Weeds and Invasive Plants), which unfortunately is no longer functional. AGIS-WIP was intended to provide online data on invasive plants but never realised its envisioned potential.

Other arms of the ARC/PPRI contribute to public awareness by holding “Farmer’s Days” which are aimed at particular groups of farmers dealing with specific invasive species problems. For example the Cedara PPRI researchers have addressed local farmers on Australian wattles (Acacia spp.) and Parthenium (Parthenium hysterophorus) control in KwaZulu-Natal , using both English and isiZulu (another official language). They also speak to conservancy groups and growers meetings such as the Wattle Growers Union and other interested parties wanting to learn about biological control of invasive plants. Biological control researchers also usually exhibit at local agricultural shows to a more general audience in their region.

The South African National Biodiversity Institute (SANBI) now oversees SAPIA and plans to extend this valuable atlas of invasive plant distribution in South Africa into the public realm via citizen science. Most importantly, there are five field guides to invasive plants, of which Alien weeds and invasive plants (Henderson 2001) is the most comprehensive and widely used.

More formal presentations are made at meetings of the Weed Science Society, the SA Sugar Technologists’ Association Symposia, the KZN Conservation Symposia, the Symposium for Contemporary Conservation Practice, and the Greater St Lucia Wetland Park conference. In the Highveld region, the Roodeplaat PPRI researchers do similar outreach and awareness visits with conservancies, action groups and wildlife managers and breeders. Schools outreach is also carried out on an ad hoc basis, as with many other research institutions involved in research on invasive plants, but consequently has a limited reach that very much depends on the relationship between the local teachers and researchers.

9 Capacity Development/Building: Growth of Employment in the Sector

The lack of human capacity in biology in general, but in taxonomy and biological control in particular, is acknowledged by academic institutions and government entities alike (Klopper et al. 2002), but notably absent from the taxonomic literature (e.g. Smith et al. 2008; Figueiredo and Smith 2010; Von Staden et al. 2013; Pyšek et al. 2013). There are obvious implications of the shortage of taxonomic skills for the management of biological invasions. The accurate identification of invasive species is essential for appropriate regulation and for correct decisions to be made about management options. Reductions in funding of taxonomic posts worldwide results in a decrease in the number of students being trained as taxonomists and this is clearly demonstrated over the last five decades by Pyšek et al. (2013).

In an attempt to address the current and future shortfall in South African taxonomic expertise, SANBI created six posts in its Invasive Species Programme for three taxonomists and three herbarium assistant posts. The job description of the taxonomists overtly acknowledged the need for the incumbent to be primarily a research taxonomist and secondarily an assistant to ensure accurate taxonomic work is undertaken on invasive species. As a result of the limited number of qualified taxonomists emerging from South African universities, SANBI has struggled to fill these posts with personnel from a diversity of race groups.

The creation of Invasive Species Programme posts within SANBI’s biosystematics division was one attempt to foster an increase in human capacity in taxonomy. A further initiative was the implementation of a project to gather voucher specimens and DNA samples of all listed invasive species in South Africa and numerous South African species documented as invasive elsewhere in the world. This project employed interns from numerous institutions. Each intern was paired with an experienced researcher and undertook to gather DNA samples of listed invasive plant species (Boatwright et al. 2012). This project gave internship experience to 24 recently graduated students from 10 institutions with supervision from 17 researchers and managers.

Lack of human capacity was also identified as a major shortcoming in invasive species management in general and in biological control in particular (Downs 2010). In order to address the lack of students entering the field of biological control research, government funds were allocated to a vacation mentorship program. Students on vacation were given a stipend to work at research institutions working in biological control (Downs 2010). The success of this program is recorded by the independent assessors, “Over the duration of the funding cycle, more than 70 students have benefitted from this DEA /NRMP-funded capacity-building programme: for the students, it has proved to be a formative experience in their careers, and for some, life-changing”.

SANBI’s Invasive Species Programme (now the Biological Invasions Directorate) embarked on a transformative mentoring programme (Ivey et al. 2013) in which inexperienced and early career researchers and managers were paired with very experienced and often retired researchers within the life sciences, conservation or invasive species field. This programme was fortunate to have adequate funding to invest in mentors, which resulted in rapid development of the mentees and an increased retention of staff in the field of invasive species management.

Zachariades et al. (2017) highlight the South African Government’s Strategy for Management of Biological Invasions that calls for a doubling of “biological control research capacity in South Africa over the next decade”. In order to achieve this, the number of researchers in the field of biological control would need to grow by 28% to 50, the technical support staff numbers would need to grow by 32% to 50 and the number of students in the field (mainly postgraduate) would need to grow by 27% to 70 students. If adequate and assured funding is forthcoming this may be achievable. In addition, the number of implementation officers and mass-rearing technicians need to increase by 63% and 61% respectively in order to meet the stated strategic objectives (Zachariades et al. 2017).

The movement of funds from government to some research units was streamlined in 2017 by the formation of the Centre for Biological Control (CBC). The government confirmed these funds for a 3-year cycle, allowing the CBC to offer post-graduate student support. Mass-rearing of biological control agents has also created employment, and for disabled people in particular (Martin et al. 2018).

Since 1995, the South African Government (most recently through the Natural Resources Management Directorate) has invested over ZAR 400 million on the biological control of invasive alien species alone, of which 70% was spent in the last 8 years. While research entities in biological control and management of biological invasions were able to create contract work for many new employees, the uncertainty of long-term work prospects have been detrimental to the retention of skilled staff. In 2017, SANBI lost a number of staff members from the former Invasive Species Programme due to uncertainty about future government support for the research and implementation programme. Likewise in 2018 the Agricultural Research Council—Plant Protection Research Institute at Cedara relinquished up to eight posts due to budget uncertainty. All the good of investment in training and mentorship can be swiftly undone by financial insecurity. This will likely impact other potential students considering a possible future in these sectors.

10 What Do Other Countries Do?

South African efforts at education, outreach and awareness around invasive species, compare well with those in other parts of the world. However, understandably each country tends to take a local approach to their own species and associated public responses. Nevertheless, sharing of ideas and methods seems to be an obvious practice that should be encouraged. International funding agencies either linked to the United Nations, such as UNEP (the United Nations Environmental Programme) and the Global Environment Facility (GEF) in association with not-for-profit organisations such as CABI (the Centre for Agriculture and Biosciences International) have taken the lead in funding outreach efforts in less-developed nations. In association with the Environmental Council of Zambia (ECZ), this type of support has helped foment discussion on a national invasive species strategy (ECZ 2007), and the production of excellent information material. The same organisations have partnered with Ghana’s Council for Scientific and Industrial Research to produce awareness material, including simple but applicable teaching suggestions, such as generating lists of local names of invasive alien plant species and comparing their seed germination rates against those of native plants (CSIR, Ghana, 2007). Further from home, Indonesia has developed a National Invasive Species Strategy, with assistance from CABI, GEF and UNEP, in reaction to invasions in their forest ecosystems (Setiawati et al. 2014). Such international involvement raises the potential of being perceived as interference in national government, but also presents the opportunity for a central clearing-house for ideas and recommendations on how the world should deal with invasive species. Notably, awareness-raising about invasive species ranked higher in Africa, Asia, South America and Oceania, than it did in Europe and North America, in a global survey of invasive species specialists and stakeholders (Dehnen-Schmutz et al. 2018). This reinforces the conclusion that people only notice invasive species when they intrude upon their lives and livelihoods. Given that new records of invasive species in new places shows no indication of levelling off, let alone nearing saturation (Seebens et al. 2017), invasive species’ control policies are multiplying worldwide. Therefore, centralisation of knowledge and responses to invasive species at every level, including education and awareness, should be seriously contemplated. Nevertheless, local problems with local solutions should remain at the core of such efforts.

11 Discussion

Education and public awareness efforts centred on invasive species in South Africa are extensive, broad-based and multi-facetted, but not comprehensive, and most people are still unaware of what invasive species are, and how they impact on our lives. For example, the 2013 State of the City of Cape Town report found that most Capetonians have no direct contact with native plant diversity, even though they live in one of the world’s six floral kingdoms, in one of the most bio-diverse countries in the world (Martin et al. 2018). Perhaps this is not surprising, as despite being utterly dependant on nature, we are increasingly separated from it (Turner et al. 2004; Silvertown et al. 2013). Engagement with invasive species is clearly not a priority for most people who are largely indifferent to the issue, if not actually opposed to invasive species control. In most cases, however, educating respondents about the impacts of aliens on their lives swings opinions in favour of their control (Novoa et al. 2017). Personalised ecology is a logical, new way, of looking at our world (Gaston et al. 2018).

The school curriculum is therefore an important opportunity to spread quality, balanced information about invasive species to the most influential component of the South African population—the next generation. The topic should be at least recapped in the final year (Grade 12) school syllabus, so that it can be regularly examined, as evolution is now (Sanders 2018). For example, the inclusion and expansion of relevant material about biological invasions in school textbooks should be accompanied by a change in the way in which science is taught in South African schools (Ramnarain and Padayachee 2015), moving from being the fact-driven, “science of life”, to a “science of living” that includes extrinsic factors such as politics, economy and even religion, all of which make us fascinating biological entities (le Grange 2008). In addition to new teaching material, external educators such as the Iimbovane Outreach Project and Ecoschools can continue to play an important role in helping to elevate the awareness of invasive species.

Universities and other higher education centres are probably reaching two to three thousand, high-performing and largely motivated young South Africans each year. Given that these graduates and postgraduates will become the next set of decision-makers in South African society, this is an important group of citizens to influence. Although the teaching of invasion biology occurs in some tertiary institutions, it is not ubiquitous and has not reached most technical colleges. This essentially means that relatively few graduates will be well-equipped to deal with issues around invasive species.

Adult education through exhibitions and other outreach exercises, including social media, internet platforms and farmers’ days, clearly have the potential to reach another broad slice of South African Society. Internet access to information has the advantage of being always on. The power of being able to Google “Prickly Pear” to settle an argument on its alien or native origin cannot be underestimated, whether that happens in a schoolyard or a shebeen (bar). Unfortunately, it is the one aspect of South African awareness programmes that is under most threat. The withdrawal of funding for initiatives such as invasives.org leaves them vulnerable to decay and collapse, or worse, potential misinformation and bias. Marrying the invasives.org web presence to other citizen science projects such as mapping weeds, under the auspices of an organisation like SANBI , could be a solution to rescuing this resource before it fades away.

South Africa has turned the control of invasive species into an industry, creating more than 20,000 jobs, with additional employment opportunities arising from “value-added products” (van Wilgen et al. 2020, Chap. 21). Because training of people employed in the control projects is expensive, the numbers of people who can be intensively trained is limited because this diverts funds away from direct job creation (Ivey et al. 2013). Other specific interventions like the Rhodes University short course have trained over 280 delegates in positive aspects and outcomes of invasive species management through biological control. However, that averages out at less than 10 practitioners per year, and these may not deliver the invasive plant control solutions their clients are looking for, since landowners often seek unrealistic, quick-fix solutions to invasive plant problems. Changes in property legislation will encourage further need for trained invasive species specialists, opening up the possibility of private sector involvement in what presents itself as a long-term commercial opportunity for training. The impetus surrounding invasive species control and awareness in South Africa is at an important juncture.

Citizen Science offers many opportunities for monitoring aliens and educating people via web linked devices (Hulbert 2016). A partnership of government-funded biodiversity efforts, overseen by SANBI offers the best way forward to enlighten the South African populace about invasive species, perhaps within their iNaturalist portal. Incorporating this information platform and topic into the school curriculum and enlisting other interested “corporate” partners, such as South African farmers, could strengthen the quality and usefulness of the information on offer (e.g. Hurley et al. 2017). Nevertheless, in a world full of myriad pressures and worries, why should anyone create additional space to learn about invasive species? The solution seems to lie in personalising the invasive plants. Surveys consistently show that the general public do not care about aliens unless they themselves are directly affected (Colton and Alpert 1998; Genovesi 2005; Novoa et al. 2017; Silvertown et al. 2013). A weed like Parthenium hysterophorus could be tested as local focus, alien species. It produces masses of extremely allergenic pollen that causes skin rashes, and is unpalatable to livestock. It is equivalent to Ragweed (Ambrosi artemisiifolia) which afflicts 33 million Europeans every year with its highly allergenic pollen and adds about 100 million euros to the European health burden (Mouttet et al. 2019; Schaffner et al. 2018). This is leading to support in Europe for the biocontrol of ragweed, and should be seen as an additional nature-based intervention for improving health and wellbeing (Shanahan et al. 2019).

There are multiple levels at which awareness of invasion biology can continue to be advanced through education , training and capacity-building in South Africa. In addition to highlighting what is being done, we have also attempted to show gaps that need to be filled. Providing a co-ordinated approach is vital to ensure that future generations of South African are aware of the invasive species already around them and to take part in the prevention of future invasions.

References

Ball DL, Cohen DK (1996) Reform by the book: what is—or might be—the role of curriculum materials in teacher learning and instructional reform? Educ Res 25:6–14. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X025009006

Blossey B, Dávalos A, Simmons W et al (2018) A proposal to use plant demographic data to assess potential weed biological control agents impacts on non-target plant populations. BioControl 63:461–473. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10526-018-9886-4

Boatwright JS, Sethusa MT, Maurin O et al (2012) Progress towards DNA barcoding of invasive species in South Africa. S Afr J Bot 79:178–179

Bremner A, Park K (2007) Public attitudes to the management of invasive non-native species in Scotland. Biol Conserv 139:306–314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2007.07.005

Clitheroe F, Doidge M, Marsden S et al (2007) Focus on life sciences grade 12 teacher’s guide. Maskew Miller Longman, Cape Town

Clitheroe F, Dempster E, Doidge M et al (2009) Focus on Life Sciences Grade 11. Learner’s book. Maskew Miller Longman, Cape Town

Coetzee JA, Hill MP, Schlange D (2009) Potential spread of the invasive plant Hydrilla verticillata in South Africa based on anthropogenic spread and climate suitability. Biol Invasions 11:801–812. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-008-9294-2

Colton TF, Alpert P (1998) Lack of public awareness of biological invasions by plants. Nat Area J:262–266

Council for Scientific and Industrial Research. Training needs assessment. Water Research Institute (WRI) (CSIR). Accra, Ghana, July 2007

Crump CM, Byrne MJ, Croucamp W (2000) A South African interactive arthropod exhibition. J Biol Educ 35(1):12–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/00219266.2000.9655729

Davies SJ, Measey GJ, du Plessis D et al (2016) Science and education at the Centre for Invasion Biology. In: Castro P et al (eds) Biodiversity and education for sustainable development. Springer International Publishing Switzerland, pp 93–105. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-32318-3_7

Davies SJ, Jordaan M, Karsten M et al (2020) Experience and lessons from alien and invasive animal control projects in South Africa. In: van Wilgen BW, Measey J, Richardson DM, Wilson JR, Zengeya TA (eds) Biological invasions in South Africa. Springer, Berlin, pp 625–660. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-32394-3_22

De Wit MP, Crookes DJ, van Wilgen BW (2001) Conflicts of interest in environmental management: estimating the costs and benefits of a tree invasion. Biol Invasions 3(2):167–178. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1014563702261

Dehnen-Schmutz K, Boivin T, Essl F et al (2018) Alien futures: what is on the horizon for biological invasions? Divers Distrib 24:1149–1157. https://doi.org/10.1111/ddi.12755

Department of Basic Education (2011) Curriculum and assessment policy statement grades 10–12: life science. National Curriculum Statement, Cape Town

Downs CT (2010) Is vacation apprenticeship of undergraduate life science students a model for human capacity development in the life sciences? Int J Sci Educ 32:687–704. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500690903075004

Dzerefos C (2018) Supporting food security through inquiry-based learning in the WESSA Eco-Schools programme. Plant the Seed. JET Bulletin December 2018, pp 9–11

Environmental Council of Zambia (2007) Invasive plant management training modules for Zambia. Under the UNEP/GEF-funded project: removing barriers to invasive plant management in Africa

Estévez RA, Anderson CB, Pizarro JC et al (2015) Clarifying values, risk perceptions, and attitudes to resolve or avoid social conflicts in invasive species management. Conserv Biol 29:19–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.12359

Figueiredo E, Smith GF (2010) The colonial legacy in African plant taxonomy. S Afr J Sci 106(3/4):1–4. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajs.v106i3/4.161

Gaston KJ, Soga M, Duffy JP et al (2018) Personalised ecology. Trends Ecol Evol 33:916–925

Genovesi P (2005) Eradications of invasive alien species in Europe: a review. Biol Invasions 7:127–133. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-004-9642-9

Giordano T, Blignaut J, Marais C (2012) Natural resource management — an employment catalyst: the case of South Africa. Dev Bank South Afr (DBSA) Dev Plan Div Work Pap Ser No. 33

Henderson L (2001) Alien weeds and invasive plants. Handbook No. 12. Plant Protection Research Institute, Agricultural Research Council, Pretoria, South Africa

Hill MP, Moran VC, Hoffmann JH et al (2020a) More than a century of biological control against invasive alien plants in South Africa: a synoptic view of what has been accomplished. In: van Wilgen BW, Measey J, Richardson DM, Wilson JR, Zengeya TA (eds) Biological invasions in South Africa. Springer, Berlin, pp 549–568. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-32394-3_19

Hill MP, Coetzee JA, Martin GD et al (2020b) Invasive alien aquatic plants in South African freshwater ecosystems. In: van Wilgen BW, Measey J, Richardson DM, Wilson JR, Zengeya TA (eds) Biological invasions in South Africa. Springer, Berlin, pp 95–112. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-32394-3_4

Hulbert JM (2016) Citizen science tools available for ecological research in South Africa. S Afr J Sci 112:1–2. https://doi.org/10.17159/sajs.2016/a0152

Hurley BP, Slippers B, Sathyapala S et al (2017) Challenges to planted forest health in developing economies. Biol Invasions 19:3273–3285. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-017-1488-z

Isaac T (2012) Understanding life sciences. Grade 11, 3rd edn. Learner’s book. Pulse Education, South Africa. ISBN 978 1920 1922 66

Ivey P, Geber H, Nänni I (2013) An innovative South African approach to mentoring novice professionals in biodiversity management. Int J Evid Based Coach Ment 11:85–111. https://radar.brookes.ac.uk/radar/items/0a29de3a-bdc8-4981-97f8-55ff63d19234/1/. Accessed 13 Feb 2019

Klopper RR, Smith GF, Chikuni AC (2002) The global taxonomy initiative in Africa. Taxon 51:159–165. https://doi.org/10.2307/1554974

Le Grange L (2008) The history of biology as a school subject and developments in the subject in contemporary South Africa. South Afr Rev Ed 14:89–105

Le Grange L (2010) The environment in the mathematics, natural sciences, and technology learning areas for general education and training in South Africa. Can J Sci Math Technol Educ 10:13–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/14926150903574247

Le Grange L, Ontong K (2018) Towards an integrated school geography curriculum: the role of place-based education. Alternation 21:12–36. https://doi.org/10.29086/2519-5476/2018/sp21a2

Le Grange L, Reddy C, Beets P (2012) Socially critical education for a sustainable Stellenbosch. In: Swilling M, Sebitosi B, Loots R (eds) Sustainable Stellenbosch: opening dialogues. African Sun Media, Stellenbosch, pp 310–321

Le Maitre DC, van Wilgen BW, Gelderblom CM et al (2002) Invasive alien trees and water resources in South Africa: case studies of the costs and benefits of management. For Ecol Manage 160:143–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-1127(01)00474-1

Le Maitre DC, Blignaut JN, Clulow A et al (2020) Impacts of plant invasions on terrestrial water resources in South Africa. In: van Wilgen BW, Measey J, Richardson DM, Wilson JR, Zengeya TA (eds) Biological invasions in South Africa. Springer, Berlin, pp 429–456. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-32394-3_15

Magadlela D, Mdzeke N (2004) Social benefits in the Working for Water programme as a public works initiative: working for water. S Afr J Sci 100(1):94–96

Martin GD, Hill MP, Coetzee JA et al (2018) Synergies between research organisations and the wider community in enhancing weed biological control in South Africa. BioControl 63(3):437–447. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10526-017-9846-4

Mouttet R, Augustinus B, Bonini M et al (2019) Estimating economic benefits of biological control of Ambrosia artemisiifolia by Ophraella communa in southeastern France. Basic Appl Ecol 33:14–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.baae.2018.08.002

Nair M (2018) The effectiveness of South African eco-schools in promoting environmental literacy. Unpubl Hons project, School of Animal Plant and Environmental Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

Novoa A, Dehnen-Schumtz K, Fried J et al (2017) Does public awareness increase support for invasive species management? Promising evidence across taxa and landscape types. Biol Invasions 19:3691–3705. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-017-1592-0

Novoa A, Shackleton R, Canavan S et al (2018) A framework for engaging stakeholders on the management of alien species. J Environ Manage 205:286–297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2017.09.059

O’Connor T, van Wilgen BW (2020) The impact of invasive alien plants on rangelands in South Africa. In: van Wilgen BW, Measey J, Richardson DM, Wilson JR, Zengeya TA (eds) Biological invasions in South Africa. Springer, Berlin, pp 457–486. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-32394-3_16

Pyšek P, Hulme PE, Meyerson LA et al (2013) Hitting the right target: taxonomic challenges for, and of, plant invasions. AoB PLANTS 5:plt042. https://doi.org/10.1093/aobpla/plt042

Ramnarain U, Padayachee K (2015) A comparative analysis of South African Life Sciences and Biology textbooks for inclusion of the nature of science. S Afr J Educ 35:1–8. https://doi.org/10.15700/201503062358

Richardson DM, Abrahams B, Boshoff N et al (2020) South Africa’s Centre for Invasion Biology: an experiment in invasion science for society. In: van Wilgen BW, Measey J, Richardson DM, Wilson JR, Zengeya TA (eds) Biological invasions in South Africa. Springer, Berlin, pp 875–912. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-32394-3_30

Sanders M (2018) The unusual case of evolution education in South Africa. In: Borgerding LA, Deniz H (eds) Evolution education around the globe. Springer, Cham, pp 409–428. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-90939-4_22

Sanders M, Makotsa D (2016) The possible influence of curriculum statements and textbooks on misconceptions: the case of evolution. Educ Change 20:1–23. https://doi.org/10.17159/1947-9417/2015/555

Schaffner U, Steinbach S, Müller-Schärer H (2018) Projecting the economic benefits of biological control of common ragweed in Europe. Abstracts of the XV International Symposium on the Biological Control of Weeds, Engelberg, Switzerland, 27–31 August 2018

Sci-Fest Africa (2019). http://www.scifest.org.za/. Accessed 6 May 2019

Seebens H, Blackburn TM, Dyer EE et al (2017) No saturation in the accumulation of alien species worldwide. Nat Commun 8:14435. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms14435

Setiawati T, Ratnaningsih S, Wanto A (2014) Report on the management of invasive species in Indonesia Forestry Sector. Ministry of Forestry, Republic of Indonesia

Shackleton RT, Witt AB, Piroris FM et al (2017) Distribution and socio-ecological impacts of the invasive alien cactus Opuntia stricta in eastern Africa. Biol Invasions 19:2427–2441. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-017-1453-x

Shackleton RT, Novoa A, Shackleton CM et al (2020) The social dimensions of biological invasions in South Africa. In: van Wilgen BW, Measey J, Richardson DM, Wilson JR, Zengeya TA (eds) Biological invasions in South Africa. Springer, Berlin, pp 697–726. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-32394-3_24

Shanahan DF, Astell-Burt T, Barber EA et al (2019) Nature-based interventions for improving health and wellbeing: the purpose, the people and the outcomes. Sports 7:141. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports7060141

Silvertown J, Buesching CD, Jacobson SK et al (2013) Citizen science and nature conservation. In: Macdonald DW, Willis KJ (eds) Key topics in conservation biology 2. Wiley Blackwell, Oxford, pp 127–142. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118520178.ch8

Smith GF, Buys M, Walters M, Herbert D et al (2008) Taxonomic research in South Africa: the state of the discipline. S Afr J Sci 104:254–256

Turner W, Nakamura T, Dinetti M (2004) Global urbanization and the separation of humans from nature. BioScience 54:585–590. https://doi.org/10.1641/0006-3568(2004)054[0585:GUATSO]2.0.CO;2

van Wilgen BW (2012) Evidence, perceptions, and trade-offs associated with invasive alien plant control in the Table Mountain National Park, South Africa. Ecol Soc 17:23–25. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-04590-170223

van Wilgen BW (2018) The management of invasive alien plants in South Africa: strategy, progress and challenges. Outl Pest Manage 29:13–17. https://doi.org/10.1564/v29_feb_04

van Wilgen BW, De Wit MP, Anderson HJ et al (2004) Costs and benefits of biological control of invasive alien plants: case studies from South Africa: Working for Water. S Afr J Sci 100:113–122

van Wilgen BW, Forsyth GG, Le Maitre DC et al (2012) An assessment of the effectiveness of a large, national-scale invasive alien plant control strategy in South Africa. Biol Conserv 148:28–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2011.12.035

van Wilgen BW, Davies SJ, Richardson DM (2014) Invasion science for society: a decade of contributions from the Centre for Invasion Biology. S Afr J Sci 110(7/8), Art. #a007 https://doi.org/10.1590/sajs.2014/a0074

van Wilgen BW, Wilson JR, Wannenburgh A et al (2020) The extent and effectiveness of alien plant control projects in South Africa. In: van Wilgen BW, Measey J, Richardson DM, Wilson JR, Zengeya TA (eds) Biological invasions in South Africa. Springer, Berlin, pp 593–624. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-32394-3_21

Von Staden L, Raimondo D, Dayaram A (2013) Taxonomic research priorities for the conservation of the South African flora. S Afr J Sci 109(3/4), Art. #1182. https://doi.org/10.1590/sajs.2013/1182

Weaver KN, Hill JM, Martin GD et al (2017) Community entomology: insects, science and society. J New Gen Sci 15:176–186

Webb J, Freedman R, de Fontaine J, Simenson IM (2012) Solutions for all life sciences, Grade 11. Learner’s Book. Macmillan Education, South Africa. ISBN 9781431010486

Weeks FJ (2015) The role of entomology in environmental and science education: comparing outreach methods for their impact on student and teacher content knowledge and motivation. Unpublished PhD. Open Access Dissertations. 587. https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/open_access_dissertations/587

Zachariades C, Paterson ID, Strathie LW et al (2017) Assessing the status of biological control as a management tool for suppression of invasive alien plants in South Africa. Bothalia 47:1–19. https://doi.org/10.4102/abc.v47i2.2142

Zengeya TA, Kumschick S, Weyl OLF et al (2020) An evaluation of the impact of alien species on biodiversity in South Africa using different assessment methods. In: van Wilgen BW, Measey J, Richardson DM, Wilson JR, Zengeya TA (eds) Biological invasions in South Africa. Springer, Berlin, pp 487–512. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-32394-3_17

Zimmermann HG, Hoffmann JH, Moran VC (2004) Biological control in the management of invasive alien plants in South Africa, and the role of the Working for Water Programme: working for water. S Afr J Sci 100:34–40

Acknowledgements

Many colleagues contributed information and ideas for this chapter. They include Sarah Davies, Kay Montgomery, Simon Gear, Lesley Henderson, Hildegard Klein, Debbie Muir, Tessa Oliver, Lorraine Strathie, Liame van der Westhuizen and Arne Witt. Two anonymous referees gave valuable comments which improved the final work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.