Abstract

The aim of this study was to identify the role of field margin habitats in preserving the diversity and abundance of ground beetle assemblages, including potentially entomophagous species and those with conservation status in Poland. Research material was collected in 2006–2007 in four types of margin habitats – a forest, bushes, ditches and in two arable fields. Insects were captured into pitfalls, without preservation liquid or bait added to the traps. Traps were inspected twice a week, between May and August, and one sample was a weekly capture. In field margin habitats the most abundant species were Limodromus assimilis, Anchomenus dorsalis, Pterostichus melanarius and Carabus auratus. A lower abundance of species was noted on fields, with dominant Poecilus cupreus and P. melanarius. The group of zoophagous carabids found in our study includes 30 species from field margin habitats, i.e. 37.5% of all captured Carabidae taxa and 58.3% of all specimens. The share of aphidophagous species was 84.9% among bushes, 86.7% near ditches, and 88.0% in the forest habitat. Several species captured during the study are under protection in Poland. These include the partly protected Carabus convexus, which also has the status of near threatened species, the partly protected Calosoma auropunctatum, and Broscus cephalotes. Considering all the investigated field margin habitats, ground beetles were most numerous in the oak-hornbeam habitat, defined as bushes, formed predominantly by Prunus spinosa, Crataegus leavigata, Sambucus nigra and Rosa canina. Thus, this habitat was the most important reservoir/refugium for the ground beetles.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Field margin habitats are increasingly considered for their importance, including a role as windbreaks, shelterbelts and migration corridors in European Union policy (Alemu 2016). An extensive report on “European Crop Protection” presents different types of field margins, with emphasis on their multiple functions in arable farming, management options for these specific ecosystems, as well as their significance in agri-environment schemes, which is mentioned by Holland et al. (2017). The authors emphasize the role of these habitats in the promotion of biodiversity, as well as mitigating the negative effects of pesticide use. Different types of margin habitats have been identified: headlands with herbaceous vegetation, tree stands or tree lines, mid-field tree belts, shelterbelts, shrubby areas, roadsides, mid-field forests or midfield woodlots or forest islands, ditches, ponds, meadows, etc. (Šustek 1994, 1998; Marshall and Moonen 2002; Kujawa et al. 2006; Alemu 2016; Franin et al. 2016; Schirmel et al. 2016; Tscharntke et al. 2016; Fusser et al. 2017; Holland et al. 2017; Ingrao et al. 2017; Medeiros et al. 2018). The multifunctional role of these habitats consists in: increasing the number of natural enemies of pests; increasing the biodiversity of wild organisms; providing primary food or alternative food sources for beneficial entomofauna, including pollinators, parasitoids and predators; providing sites for nesting, sheltering and overwintering of invertebrates, mammals and birds; reducing the use of chemicals in crops, and the transfer of pollutants to different areas of the landscape (e.g. Marshall and Moonen 2002; Medeiros et al. 2018).

The role of margin habitats often depends on the group of studied animals. For example, mid-field forests, woodlots and shrubby habitats have been found more beneficial for the biodiversity of the assemblages of carabids, spiders and other predators than habitats with herbaceous vegetation (Schirmel et al. 2016; Ingrao et al. 2017). Generally, habitats with herbaceous vegetation, and particularly grasslands, have a less important role (Morris et al. 2010). However, grasslands on field margins have been poorly investigated in terms of insects and other arthropods, even though they cover over 81 million hectares of land in the EU (ÓHuallachain et al. 2014). Previous studies have consistently indicated, for example, that fields intersected by rows of trees and other wild plants, with greater landscape patchiness, were characterised by greater abundance of useful insects (e.g. Basedow 1990; de Bruin et al. 2010; Bennewicz 2011, 2012; Tscharntke et al. 2016). Different authors have indicated the positive effect of these environmental islands on the abundance of hoverflies, carabids, parasitoids and pollinators in agroecosystems (Bosch 1987; Welling 1990; Riedel 1991; Ruppert and Molthan 1991; Barczak et al. 2000; Banaszak and Cierzniak 2002; Bennewicz 2011).

Most imagines of Carabidae are polyphagous, both predators and plant eaters, especially seed eaters, and some species are parasites (Kotze et al. 2011). Kulkarni et al. (2017) summarized that in temperate agroecosystems, carabid beetles (Coleoptera: Carabidae) are key members of epigaeic invertebrate assemblages, with the potential to provide valuable ecological services. In addition to their significant role as predators of invertebrate pests, carabids consume substantial numbers of seeds produced by numerous weedy species, and in so doing, can reduce weed populations through regulation of the weed seedbank (Honĕk et al. 2003; Kulkarni et al. 2017; Saska et al. 2019).

Carabidae show high mobility between different ecosystems (Šustek 1994; Kujawa et al. 2006; Kosewska et al. 2007; Twardowski and Pastuszko 2008; Kotze et al. 2011; Jaskuła and Stępień 2012; Ohwaki et al. 2015). In some habitats with lower plant cover rate they disperse easily, while other habitats create obstacles to their migration (Cole et al. 2012; Ohwaki et al. 2015). Generally Carabidae, like other invertebrates, respond positively to habitat diversity by increased abundance and species richness (Kromp and Steinberger 1992; Yu et al. 2006; Cameron and Leather 2012; ÓHuallachain et al. 2014; Franin et al. 2016; Schirmel et al. 2016).

The aim of this study was to identify the ground beetle assemblages and the role of field margin habitats adjacent to arable fields in preserving their diversity and abundance, including zoophagous species and those with conservation status in Poland.

The hypothesis assumes that field margin habitats constitute a reservoir of ground beetles and potential centers of their dispersal to agroecosystems.

Material and methods

Study area

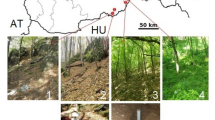

Study sites were established in the Lower Vistula Valley in two arable fields and four non-arable field margin habitats adjacent to them (Fig. 1).

The first field (Field I - PI), used for growing triticale in 2006 and winter wheat in 2007, bordered two margin habitats: headland on moist soil with herbaceous vegetation in a basin near a ditch (Ditch 1 - R1), and a habitat with dense bushes and specimen trees (Bushes - K).

The second field (Field II - PII), used for growing sugar beet in 2006 and peas in 2007, bordered two other field margin habitats: headland with herbaceous vegetation on dry peat soil (Ditch 2 - R2), and mid-field forest, defined as a forest (Forest - L) (Fig. 1).

Ditch 1 (R1) is located in an oak-hornbeam forest habitat; the ditch is free from shrubs, unsheltered and strongly insolated; dominant plant species include Elymus repens, Matricaria perforata, Poa pratensis, Convolvulus arvensis, Bromus inermis and Rubus caesius. Over the four years of observation the E. repens covered almost 95% of the study plot, and other grasses were found as an admixture. As with other plant species, only C. arvensis increased in abundance.

Bushes (K) are located in an oak-hornbeam forest habitat; the uppermost layer of vegetation was formed by Quercus robur and Tilia cordata. The shrub layer was formed by Prunus spinosa, Crataegus leavigata, Sambucus nigra, and Rosa canina, while the dominant herbaceous species were E. repens, Lamiun album, Urtica dioica, Artemisia vulgaris, Melandrium album, and Poa sp.. Over the four years of the study there was a marked increase in the abundance of U. dioica and Conium maculatum, and an expansion of Solidago serotina.

Forest (L) is a riparian forest formed mainly by Alnus glutinosa and grows on peat soil. Dominant species in the layer of herbaceous vegetation included U. dioica, B. inermis, Impatiens parviflora, Galium aparine and E. repens. Deep in the forest there was a well-developed shrub layer dominated by S. nigra. The herbaceous layer after four years of study was characterised by an abundance of U. dioica and B. inermis, while other plant species were represented by single specimens.

Ditch 2 (R2) is a wide ditch filled with water and separating two fields. The most abundant plant species included B. inermis, E. repens, Tanacetum vulgare, Festuca rubra, U. dioica, and Cirsium arvense. After four years of study B. inermis was still dominant, and the quantity of C. arvense and T. vulgare increased slightly. Other plant species observed on an annual basis were represented only by single specimens.

Sampling and analysis methods

Research material was collected and taxonomically identified in 2006–2007 for field margin habitats - forest L, bushes K, ditches R1, R2, and for two arable fields (PI, PII). Ground beetle species and their trophic preferences were identified and described using keys by Wrase (2004) and Müller-Motzfeld (2006), according to the system of the Catalogue of Palearctic Coleoptera (Löbl and Löbl 2017).

In order to perform a qualitative and quantitative analysis of ground beetles (Carabidae) assemblages, insects were captured into traps (three traps in each site), without preservation liquid or bait added to them. Pitfalls (plastic cups 10 cm in diameter) were buried in the ground with their edges slightly below ground level and arranged in triplicates every 10 m on each site, 25 m from the edge of the field, and in field margin habitats along the edge adjacent to fields (Fig. 1). The traps were sheltered from the top with plastic, transparent roofs, protecting them from flooding with rainwater. Traps were inspected twice a week, between May and August, and one sample was a weekly capture (six replications as a sum as each site). The specimens of conservation status species (Głowaciński 2002; Rozporządzenie 2014) were identified alive and they were released into distant and similar habitats, while others were transported in plastic containers filled with a 20% solution of ethylene glycol to the laboratory in order to determine their species/genus.

The significance of differences for the calculated values of the Shannon-Wiener diversity index H` (Shannon and Weaver 1963) between assemblages of ground beetles in different habitats was established based on the Hutcheson test (Hutcheson 1970), using the Student t-test (p ˂ 0.05).

Results

The list of all 80 captured Carabidae species is presented in Table 1. In total, 17,313 beetles were caught. The number of species was higher in field margin habitats (77) and slightly lower in the fields (51). The most numerous species represented the following genera: Amara (14 species), Carabus (7), Harpalus (10) and Pterostichus (7). The most numerous species were: Pterostichus melanarius (3684 individuals), found in similar numbers in the study sites, as well as Limodromus assimilis (2248 individuals), particularly in habitats L and K, Poecilus cupreus (2138), particularly in the fields, and Anchomenus dorsalis (1471 individuals), which was relatively abundant in all study sites, but most abundant in field margin habitats, especially in K and R1 (Table 1). Other abundant species were Harpalus affinis (1024 individuals), Carabus auratus (954), Bembidion properans (876), Calathus ambiguus (579), Pseudoophonus rufipes (532), C. cancellatus (531) and Pterostichus caerulescens (436 specimens) (Table 1).

In field margin habitats, on the average, the most abundant species were P. melanarius (658.8 beetles), L. assimilis (556.8), A. dorsalis (291.3) and Carabus auratus (200.0 individuals, on the average). On the average, lower numbers of species were found on arable fields, and the dominant ones were P. cupreus (800.0 beetles), P. melanarius (524.5), followed by the A. dorsalis (153.0), H. affinis (148.5) and P. caerulescens (148.0) as well as Bembidion properans (137.5 individuals, on the average). Of note, P. cupreus preferred field PI adjacent to the headland with herbaceous vegetation (R1) and a habitat with dense bushes and specimen trees (K), similarly as it was in the case of a field PII surrounded with the forest (L) and the ditch R2 (Fig. 1, Table 1).

In both years (2006–2007) of the research, in the field PI and in the surrounding habitats K and R1, more carabids were caught than in the PII field and on the R2 ditch and in the L forest habitat (Fig. 2). The carabids were most often caught in shrubs K (average of 1928.0 specimens) adjacent to the PI field. However, in the L forest site, a greater number of ground beetles (mean of 1512.0 beetles) were captured than in the PII field (1048.5) and in the surrounding R2 habitat (mean of 973.0 individuals) (Fig. 2). It is necessary to point out that in the PI and PII fields more beetles were caught in 2007 than in 2006 (Fig. 2). On the other hand, in the border areas adjacent to the fields, in the same years it was the opposite. To summarize, in the analyzed years the fauna of ground beetles in bushes K and in the ditch RI adjacent to field PI was more abundant than in margin habitats adjacent to field PII.

Among the captured Carabidae species, 30 were zoophagous, i.e. 58.3% of all captured specimens (Table 1). Most of the zoophagous beetles were collected in the habitat with a large part of shrubs (K) – 84.9% of specimens in that habitat, and in the surrounding PI field and in the forest L, bordering the PII field – 88.0%. The smallest number of zoophagous species was recorded on open habitats, which were: PII field and in the surrounding R2 ditch (Fig. 3).

Interestingly, the abundance of zoophagous carabids was high, since we captured 17,313 individuals, which accounted for over 85.2% of all Carabidae beetles, including only 4661 specimens captured in both fields, which accounted for 31.6% of aphidophagous species and ca. 26.9% of all Carabidae captured specimens (Table 1). The relatively high percentage of zoophagous forms in the forest site suggests that this habitat could not only be a feeding place, but also a shelter for useful carabids and a key site for their dispersal into the fields, as in the case of the habitat K. This is confirmed by the following data. In the field PI, adjacent to bushes K and ditch R1 the share of aphidophages was 87.4%, and 94.0% in the field PII, adjacent to the forest L and ditch R2.

The analysis of species diversity for Carabidae in 2006–2007 demonstrated that mean values of the H` index, in the range of 3.03–3.70, were higher in field margin habitats (3.40–3.70) compared to adjacent fields (3.03–3.30) (Fig. 4). However, no significant differences between the compared areas were found (p ˃ 0.05). It can be concluded that richness and diversity are higher in field margin habitats than in arable fields. The presented data show that the habitats with bushes K and ditch R1 adjacent to field PI were the most attractive for the ground beetles.

Discussion

All captured Carabidae species represented ca. 17% of the entire fauna of carabids in Poland (Aleksandrowicz 2004; Jaskuła and Stępień 2012). Several of them represented species from the genus Carabus (7 species), and there was one individual of Calosoma auropunctatus protected in Poland until recently, which accounts together for ca. 28% of all species from this genera in Poland. However, under recent legislation (Rozporządzenie 2014) only four species from the genus Carabus are strictly protected, and further 18 are partly protected in Poland. This includes one partly protected species captured during our study, Carabus convexus, which is listed in the Polish Red Data Book of Animals and has the status of near threatened (NT) (Głowaciński 2002). We also captured a single individual of Calosoma auropunctatum, which is a partly protected species (Rozporządzenie 2014). The Polish Red Data Book of Animals (Głowaciński 2002) also includes Broscus cephalotes, with the status of DD (data deficient), rarely recorded in these studies.

Ground beetles are generally regarded as predators (Bosch 1987; Węgorek and Trojanowski 1990; Holopainen and Helenius 1992; Bennewicz and Kaczorowski 1999; Barczak et al. 2000; Kotze et al. 2011). Some of them are more specialized, such as those from the genus Calosoma, feeding mainly on the caterpillars of butterflies, or species from the genus Cychrus (not recorded in our study), feeding on snails. Most carabids are, however, predators utilizing a wide range of foods (polyphagous) (Kotze et al. 2011). Shrubby habitats among fields can vary considerably in terms of the trophic structure of the local Carabidae assemblages, and in most cases the most numerous are zoophagous species, including aphidophages (Bosch 1987; Holopainen and Helenius 1992; Bennewicz and Kaczorowski 1999; Barczak et al. 2000). There are also haemizoophagous species, which feed on mixed, animal and plant food, such as Harpalus, Pseudoophonus and Amara (Barczak et al. 2000; Aleksandrowicz 2004). Both the genera were represented in our research. Many species of Carabidae, so-called seed predators, including Harpalus, Pterostichus and others show different trophic strategies (Honĕk et al. 2003; Birthisel et al. 2014; Gallandt 2006; Saska et al. 2019). These species are a significant cause of weed mortality in agroecosystems (Gallandt 2006).

In our study the group of zoophagous or potentially aphidophagous carabids includes 30 species from field margin habitats, i.e. 58.3% of all captured Carabidae specimens. Aphidophagous carabids include species from the genus Agonum, Bembidion, Calathus, as well as Amara apricaria, A. aulica, A. plebeja, Anchomenus dorsalis, Limodromus assimislis, Harpalus affinis, Loricera pilicornis, Poecilus cupreus, P. rufipes, Pterostichus caerulescens, P. niger, P. oblongopunctatus, P. strenuus, P. vernalis, P. melanarius and Synuchus vivalis (Holopainen and Helenius 1992; Barczak et al. 2000). This proves the strong biological potential of field margin habitats, especially bushes/shrubby habitats, the forest and ditches, which could be the main ecological corridors, promoting the dispersal of useful Carabidae (Šustek 1994, 1998), including potentially aphidophagous species, to agroecosystems (Holopainen and Helenius 1992; Barczak et al. 2000). This shows the clear effect of predatory Carabidae populations in the investigated field margin habitats through their dispersal into the arable fields.

Limodromus assimilis, one of the most abundant species, was found almost all over Europe and lives in wet and shady habitats, especially in deciduous and mixed forests near water (Burakowski et al. 1974), which is strongly reflected in the results from our study – the population of this species was the largest in field margin habitats: the forest L and the bushes K. Šustek (1994) stated that the gradient between forest-like corridors and fields is most effective when the corridors consist of autochtonus trees and shrubs. Those biosystems increase the migration of up to 30% of the carabid species in a forest. Different habitats are preferred by Anchomenus dorsalis, which has a similar distribution range to L. assimilis, but lives in open sunny and dry areas sometimes covered by tall loose vegetation (Burakowski et al. 1974, Porhajašová et al. 2008), which was also reflected in our study. This species was most abundant in bushes K, and least numerous in the forest L and near ditches (R1, R2), as well as in the fields (PI, PII), where dense cereal plants or sugar beet leaves covered and shaded the soil. Another species, Pterostichus melanarius, the most numerous in our study has its range in northern Europe, is eurytopic, lives in open, sunny and quite dry areas, and is often found in arable fields, but also in gardens, parks, on forest margins and roadsides (Burakowski et al. 1974). It is fully reflected in our study, showing comparable abundance of this species in all habitats. However, a related species, Poecilus cupreus, which has a wider range in Europe, is common in Poland, and lives both in open and forested areas, but also near water bodies (Burakowski et al. 1974; Barczak et al. 2000, Porhajašová et al. 2008). Harpalus affinis, a species widely distributed across Europe, polyphagous, also predatory and potentially aphidophagous, lives mainly in open, dry and sunny areas, including arable fields, fallow land and ruderal areas (Burakowski et al. 1974; Jørgensen and Lövei 1999; Barczak et al. 2000; Kulkarni et al. 2017). These preferences were confirmed in our study, since the species was least abundant in forest site L. Similar to H. affinis, P. cupreus, one of the most numerous species in crop fields (e. g. Porhajašová et al. 2008), was least abundant in forest habitat L. Another interesting species is Carabus auratus, found in western Europe and Poland, which used to be the eastern limit of its range (Burakowski et al. 1973). This carabid lives in open areas, especially in arable fields on clay soils (Burakowski et al. 1973). In our study it was relatively scarce in the fields and in the forest, but it was more numerous near ditches and among bushes.

Schirmel et al. (2016) suggested that the protection and reestablishment of woody semi-natural habitats is crucial for functionally diverse spider and carabid assemblages with a high proportion of predators, such as, e.g. Pterostichus, as in our study. This may promote the functional diversity of ecosystem service providers in adjacent agricultural fields, and may lead to enhanced pest suppression (Schirmel et al. 2016; Medeiros et al. 2018). Šustek (1994) and Taboada et al. (2010) stated that the structural type of vegetation is likely to have more effect on carabid species than plant species. For example, Šustek (1994) underlined that one of the most important factors influencing migration of forest carabids from their forest habitats into fields are the width, density and composition of the corridors, and the positive effect of the shelterbelts was observable up to 50–200 m from their margins.

Studies on vegetation and accompanying entomofauna in field margin habitats help evaluate the role of these habitats as potential refugia for useful animals in Integrated Pest Management (IPM) and as components influencing ecological balance at the level of landscape (Barczak 1993; Barczak et al. 2000; Ramsden et al. 2015; Tscharntke et al. 2016; Kadej et al. 2018). Other important aspects are the species composition and changes in plant communities, as well as the age of these field margin ecosystems (Marshall and Moonen 2002; Gaigher et al. 2016), and their structural diversity/layer structure (Taboada et al. 2010). Some researchers believe that communities of perennial vegetation with established qualitative and quantitative relationships play a greater role as more stable and richer refugia for useful fauna (Marshall and Moonen 2002; Gaigher et al. 2016), while Yu et al. (2006) recorded that the short term establishment of field margins is effective in enhancing the diversity and abundance of carabids. Furthermore, it has been emphasized that bushes among fields promote the synchronic emergence of pests and their natural enemies in diversified agricultural landscapes (e.g. Barczak 1993; Barczak et al. 2000). Therefore, they should be taken into consideration as a very important network of ecological corridors for useful arthropods, different from the surrounding habitats, and connecting separated biocenoses accompanying these mid-field/environmental islands and arable fields (Šustek 1994, 1998; Marshall and Moonen 2002; Ohwaki et al. 2015).

So-called “conservation biological control” is connected with reversing the negative effects of intensive farming on natural enemies. These include reducing pesticides, tillage, as well as the establishment of beneficial habitats to compensate for the general reduction in the quality and diversity of habitats in the agricultural landscape (Begg et al. 2017). Furthermore, sufficient research has now been done to establish that natural enemies respond positively to such conservation strategies, including plant diversification, reduced cropping intensity, and enhanced landscape composition or complexity. Many natural enemies require additional resources to supplement those obtained from pest prey or hosts. Floral resources, particularly nectar pollen and honeydew, are important dietary components for various natural enemies (Olson and Wäckers 2007; Wäckers et al. 2008). Semi-natural habitats such as bushes K and forest L in our case can also provide supplementary resources by supporting populations of alternative prey and host populations (Barczak 1993; Landis et al. 2000; Rusch et al. 2016). For carabids or some parasitoids whose life cycles include overwintering in the soil, reduced tillage reduces mortality directly, but may also influence arthropod communities, including natural enemies (Begg et al. 2017).

In Poland, where about 61% of total area is covered by farmland, nearly half of the more than 2.5 million farms are still smaller than 2 ha, and the rural landscape is relatively rich in non-crop areas (Wuczyński et al. 2011). However, in the last few years, these agricultural structures and related habitats have been severely threatened in Poland and other countries of Central and Eastern Europe, by abandonment, afforestation or agricultural intensification (Kadej et al. 2018).

Intensive farming practices have significantly reduced the fragmentation/mosaic spaces of the agricultural landscape (Rusch et al. 2016; Landis 2017; Kadej et al. 2018; Ortiz-Martinez and Lavandero 2018). The monitoring of ecological/agroecological infrastructure in the cultural landscape is one of the aspects that should be considered in ecological engineering (Franin et al. 2016; Ortiz-Martinez and Lavandero 2018). This management model should consider the fragmentation of non-arable ecosystems, i.e. polyculture (de Bruin et al. 2010; Tscharntke et al. 2016). All this should create the foundation for greening the rural economy, to prevent the progressive fragmentation and diminished role of margin habitats as hot-spots of biodiversity (Ranjha and Irmler 2013; Franin et al. 2016). Polycultural landscape means the protection of habitats with reservoirs of zoophages, which are both host plants for invertebrates, as well as invertebrates as alternative food for zoophages. Moreover, the creation of new field margin habitats can enhance the abundance and activity of natural enemies of pests (Powell 1986; Welling 1990; Barczak 1993; Barczak et al. 2000; Cole et al. 2012; Ramsden et al. 2015). This problem is related to the broadly defined so-called natural biological pest control (Ehler 1990), and augmentative biological control, as well as conservation biological control as a sustainable alternative to chemical control (Ehler 1990; van Lenteren 2012; Begg et al. 2017; van Lenteren et al. 2018).

Conclusions

-

1.

In field margin habitats the most abundant carabid species were Limodromus assimilis, Anchomenus dorsalis, Pterostichus melanarius, Harpalus affinis and Carabus auratus. A lower abundance of species was noted in arable fields, with dominant Poecilus cupreus and P. melanarius.

-

2.

The group of zoophagous carabids found in our study includes 30 species from field margin habitats, i.e. 37.5% of all captured Carabidae taxa. This proves the strong biological potential of field margin habitats from which Carabidae migrated to the adjacent arable fields.

-

3.

Several species captured during the study are under protection in Poland. These include the partly protected Carabus convexus, which also has the status of near threatened (NT) species in the Polish Red Data Book of Animals, the partly protected Calosoma auropunctatum (single captured individual), and Broscus cephalotes, listed in the Polish Red Data Book of Animals with the status data deficient (DD).

-

4.

Considering all the investigated field margin habitats, ground beetles were most numerous in the ouk-hornbeam, defined as bushes, formed predominantly by Prunus spinosa, Crataegus leavigata, Sambucus nigra and Rosa canina, with an admixture of Quercus robur and Tilia cordata specimen trees. Relatively numerous assemblages of carabids were also found near one of the ditches with herbaceous vegetation, adjacent to bushes, and in the distant riparian forest with dominant trees of Alnus glutinosa.

-

5.

The analysis of the species diversity of Carabidae revealed that mean values of the Shannon-Wiener diversity index were higher in field margin habitats compared to adjacent fields, but the differences were not statistically significant. This suggests the greater population abundance and diversity of carabid assemblages in field margin habitats compared to arable fields, but on the other hand, the dispersal of Carabidae to agroecosystems. The shrubby habitat (bushes) seemed to be the best reservoir/refugium for ground beetles.

References

Aleksandrowicz OR (2004) Biegaczowate (Carabidae). In: Bogdanowicz W, Chudzicka E, Pilipiuk I, Skibińska E (eds) Fauna Polski, Charaktystyka i wykaz gatunków, vol 1. Muzeum i Instytut Zoologii PAN, Warszawa, pp 28–42

Alemu MM (2016) Ecological benefits of trees as windbreaks and shelterbelts. Int J Ecosystm 6:10–13. https://doi.org/10.5923/j.ije.20160601.02

Banaszak J, Cierzniak T (2002) Wyspy środowiskowe krajobrazu rolniczego jako refugia owadów zapylających - próba waloryzacji. In: Banaszak J (ed) Wyspy środowiskowe, Bioróżnorodność i próby typologii, No, vol 7. Wyd Akademii Bydgoskiej, Bydgoszcz, pp 105–125

Barczak T (1993) Ekologiczne asp ekty wykorzystania parazytoidów w zwalczaniu mszycy burakowej, Aphis fabae Scop. Zesz Nauk ATR, No 57. Rozprawy, Bydgoszcz

Barczak T, Kaczorowski G, Bennewicz J, Krasicka-Korczyńska E (2000) Znaczenie zarośli śródpolnych jako rezerwuarów naturalnych wrogów mszyc. Wydawnictwa Uczelniane ATR, Bydgoszcz

Basedow T (1990) On the impact of boundary strips and hedges on aphid predators, aphid attack and the saccessity for insecticide applications on sugarbeet. Gesunde Pflanz 7:241–245

Begg GS, Cook SM, Dye R, Ferrante M, Franck P, Lavigne C, Lövei GL, Mansion-Vaquie A, Pell JK, Petit S, Quesada N, Ricci B, Wratten SD, Nicholas A, Birch E (2017) A functional overview of conservation biological control. Crop Prot 97:145–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cropro.2016.11.008

Bennewicz J (2011) Aphidivorous hoverflies (Diptera: Syrphidae) at field boundaries and woodland edges in an agricultural landscape. Pol J Entomol 80:129–149. https://doi.org/10.2478/v10200-011-0010-7

Bennewicz J (2012) Aphids (Hemiptera: Aphididae) of midfield thickets in an agricultural landscape. Pol J Entomol 81:11–33

Bennewicz J, Kaczorowski G (1999) Mszyce (Aphidodea) i biegaczowate (Carabidae) zakrzewień śródpolnych. Progr Plant Prot 39:603–607

Birthisel SK, Gallandt ER, Jabbour R (2014) Habitat effects on second-order predation of the seed predator Harpalus rufipes and implications for weed seedbank management. Biol Control 70:65–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocontrol.2013.12.004

Bosch J (1987) The influence of some dominating weeds on beneficial arthropods and pests in a sugarbeet field. Z Pflanzenkr Pflanzenschutz 94:398–408

Burakowski B, Mroczkowski M, Stefańska J (1973) (przy współpracy Makulskiego J i Pawłowskiego J) Chrząszcze Coleoptera, Biegaczowate - Carabidae, część 1, XXIII, No 2. Kat Fauny Pol, Warszawa, pp 1-233

Burakowski B, Mroczkowski M., Stefańska J (1974) (under cooperation of Makulskiego J and Pawłowski J) Chrząszcze Coleoptera, Biegaczowate - Carabidae, część 2, XXIII, No 3. Kat Fauny Pol, Warszawa, pp 1-430

Cameron KH, Leather SR (2012) How good are carabid beetles (Coleoptera, Carabidae) as indicators of invertebrate abundance and order richness? Biodivers Conserv 21:763–779. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-011-0215-9

Cole LJ, Brocklehurst S, Elston DAS, McCracken DI (2012) Riparian field margins: can they enhance the functional structure of ground beetle (Coleoptera: Carabidae) assemblages in intensively managed grassland landscapes? J Appl Ecol 49:1384–1395. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2664.2012.02200.x

de Bruin S, Jansssen H, Klompe A, Klompe L, Lerink P, Vanmeulebrouk B (2010) GAOS: special optimization of crop and nature within agricultural fields. In: Conference on Agricultural Engineering Technologies, Clermont – Ferraud, France, pp 1–10

Ehler LE (1990) Revitalizing biological control. Issues Sci Technol 7:91–96

Franin K, Barić B, Kuštera G (2016) The role of ecological infrastructure on beneficial arthropods in vineyards. Span J Agric Res 14. https://doi.org/10.5424/j.sjar.2016141-7371

Fusser MS, Pfister SC, Entling MH, Schirmel J (2017) Effects of field margin type and landscape composition on predatory carabids and slugs in wheat fields. Agric Ecosyst Environ 247:182–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2017.06.030

Gaigher R, Pryke JS, Samways MJ (2016) Old fields increase habitat heterogeneity for arthropod natural enemies in an agricultural mosaic. Agric Ecosyst Environ 230:242–250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2016.06.014

Gallandt ER (2006) Symposium how can we target the weed seedbank? Weed Sci 54:588–596. https://doi.org/10.1614/WS-05-063R.1

Głowaciński Z (2002) Czerwona lista zwierząt ginących i zagrożonych w Polsce. Kraków

Holland JM, Douma JC, Crowley L, James L, Kor L, Stevenson DRW, Smith BM (2017) Semi-natural habitats support biological control, pollination and soil conservation in Europe: A review. Agron Sustain Dev 37:31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13593-017-0434-x

Holopainen JK, Helenius J (1992) Gut contents of ground beetles (Col, Carabidae), and activity of these and other epigeal predators during an outbreak of Rhopalosiphum padi (Hom, Aphididae). Acta Agr Scand B-S P 42:57–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/09064719209410199

Honěk A, Martinkova Z, Jarosik V (2003) Ground beetles (Carabidae) as seed predators. Eur J Entomol 100:531–544. https://doi.org/10.14411/Eje.2003.081

Hutcheson K (1970) A test for comparing diversities based on the Shannon formula. J Theor Biol 29:151–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-5193(70)90124-4

Ingrao AJ, Schmidt J, Jubenville J, Grode A, Komondy L, Vander Zee D, Szendrei Z (2017) Biocontrol on the adge: field margin habitats in asparagus fields influence natural enemy-pest interactions. Agric Ecosyst Environ 243:47–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2017.04.011

Jaskuła R, Stępień A (2012) Ground beetle fauna (Coleoptera: Carabidae) of protected areas in the Łódź Province. Part I: nature reserves. Fragm Faunist 55:101–122

Jørgensen HB, Lövei GL (1999) Tri-trophic effect on predator feeding: consumption by the carabid Harpalus affinis of Heliothis armigera caterpillars fed on proteinase inhibitor-containing diet. Entomol Exp Appl 93:113–116

Kadej M, Zając K, Tarnawski D (2018) Oviposition site selection of a threatened moth Eriogaster catax (Lepidoptera: Lasiocampidae) in agricultural landscape - implications for its conservation. J Insect Conserv 22:29–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10841-017-0035-7

Kosewska A, Nietupski M, Ciepielewska D (2007) Zgrupowania biegaczowatych (Coleoptera: Carabidae) zadrzewień śródpolnych i pól z Tomaszkowa koło Olsztyna. Wiad Entomol 26:153–168

Kotze DJ, Brandmayr P, Casale A, Dauffy-Richard E, Dekoninck W, Koivula MJ, Lövei GL, Mossakowski D, Noordijk J, Paarmann W, Pizzolotto R, Saska P, Schwerk A, Serrano J, Szyszko J, Taboada A, Turin H, Venn S, Vermeulen R, Zetto T (2011) Forty years of carabid beetle research in Europe - from taxonomy, biology, ecology and population studies to bioindication, habitat assessment and conservation. Zookeys 100:55–148. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.100.1523

Kromp B, Steinberger KH (1992) Grassy field margins and arthropod diversity: a case study on ground beetles and spiders in eastern Austria (Col.: Carabidae; Arachnida: Aranei, Opiliones). Agric Ecosyst Environ 40:71–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-8809(92)90085-P

Kujawa K, Sobczyk D, Kajak A (2006) Dispersal of Harpalus rufipes (De Geer) (Carabidae) between shelterbelt and cereal field. Pol J Ecol 54:243–252

Kulkarni SS, Dosdall LM, Spence JR, Willenborg CJ (2017) Field density and distribution of weeds are associated with spatial dynamics of omnivorous ground beetles (Coleoptera: Carabidae). Agric Ecosyst Environ 236:134–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2016.11.018

Landis DA (2017) Designing agricultural landscapes for biodiversity-based ecosystem services. Basic Appl Ecol 18:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.baae.2016.07.005

Landis DA, Wratten SD, Gurr GM (2000) Habitat management to conserve natural enemies of arthropod pests in agriculture. Annu Rev Entomol 45:175–201. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ento.45.1.175

Löbl I, Löbl D (2017) Catalogue of Palaearctic Coleoptera. Archostemata–Myxophaga– Adephaga. Vol. 1. Revised and updated edition. Brill, Leiden, Boston

Marshall EJP, Moonen AC (2002) Field margins in northern Europe: their functions and interactions with agriculture. Agric Ecosyst Environ 89:5–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-8809(01)00315-2

Medeiros HR, Hoshino AT, Ribeiro MC, Morales MN, Martello F, Coelho O, Neto OCP, Carstensen DW, de Oliveira Menezes Jr A (2018) Non-crop habitats modulate alpha and beta diversity of flower flies (Diptera, Syrphidae) in Brazilian agricultural landscapes. Biodivers Conserv 27:1309–1326. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-017-1495-5

Morris AJ, Bailey CM, Dillon IA, Gruar DJ, Westbury DB (2010) Improving floristically enhanced field margins for wildlife. Asp Appl Biol 100:353–357

Müller-Motzfeld G (2006) Adephaga 1: Carabidae (Laufkäfer). In: Freude H, Harde KW, Lohse GA, Klausnitzer B (eds) Die Käfer Mitteleuropas. Spektrum, Heidelberg

ÓHuallachain D, Anderson A, Fritch R, McCormack S, Sheridan H, Finn JA (2014) Field margins: a comparison of establishment methods and effects on hymenopteran parasitoid communities. Insect Conserv Divers 7:289–307. https://doi.org/10.1111/icad.12053

Ohwaki A, Kaneko Y, Ikeda H (2015) Seasonal variability in the response of ground beetles (Coleoptera: Carabidae) to a forest edge in a heterogeneous agricultural landscape in Japan. Eur J Entomol 112:135–144. https://doi.org/10.14411/eje.2015.022

Olson DM, Wäckers FL (2007) Management of field margins to maximize multiple ecological services. J Appl Ecol 44:13–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2664.2006.01241.x

Ortiz-Martinez SA, Lavandero B (2018) The effect of landscape context on the biological control of Sitobion avenae: temporal partitioning response of natural enemy guilds. J Pest Sci 91:41–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10340-017-0855-y

Porhajašová J, Petřvalský V, Šustek Z, Urminská J, Ondrišík P, Noskovič J (2008) Long-termed changes in ground beetle (Coleoptera: Carabidae) assemblages in a field treated by organic fertilizers. Biologia 63:1184–1195. https://doi.org/10.2478/s11756-008-0179-8

Powell W (1986) Enhancing parasitoid activity in crops. In: Waage J, Greathead D (eds) Insect Parasitoids, Academic Press, pp 319–340

Ramsden MW, Menéndeza R, Leatherb SR, Wäckers F (2015) Optimizing field margins for biocontrol services: The relative role of aphid abundance, annual floral resources, and overwinter habitat in enhancing aphid natural enemies. Agric Ecosyst Environ 199:94–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2014.08.024

Ranjha M, Irmler U (2013) Age of grassy strips influences biodiversity of ground beetles in organic agroecosystems. Agric Sci 4:208–218. https://doi.org/10.4236/as.2013.45030

Riedel W (1991) Overwintering and spring dispersal of Bembidion lampros (Col., Carabidae) from established hibernation sites in a winter wheat field in Denmark. In: Polgar L et al (eds) Behaviour and impact of Aphidophaga, SPB Academic Publishing bv, pp 235–241

Rozporządzenie Ministra Środowiska (2014) z dnia 6 października 2014 r. w sprawie ochrony gatunkowej zwierząt. 2014 poz 1348

Ruppert V, Molthan J (1991) Augmentation of aphid antagonists by field margin rich in flowering plants. In: Polgar L et al. (eds) Behaviour and impact of Aphidophaga, SPB Academic Publishing bv, pp. 243–247

Rusch A, Chaplin-Kramerc R, Gardinere MM, Hawrof V, Hollandg J, Landish D, Thies C, Tscharntke T, Weisser WW, Winqvistk C, Woltzl M, Bommarcok R (2016) Agricultural landscape simplification reduces natural pest control: A quantitative synthesis. Agric Ecosyst Environ 221:198–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2016.01.039

Saska P, Honěk A, Foffová H, Martinková Z (2019) Burial-induced changes in the seed preferences of carabid beetles (Coleoptera: Carabidae). Eur J Entomol 116:133–140. https://doi.org/10.14411/eje.2019.015

Schirmel J, Thiele J, Entling MH, Buchholz S (2016) Trait composition and functional diversity of spiders and carabids in linear landscape elements. Agric Ecosyst Environ 235:318–328. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2016.10.028

Shannon CE, Weaver W (1963) The mathematical theory of communication. University of Illinois Press, Urbana

Šustek Z (1994) Windbreaks as migration corridors for carabids in an agricultural landscape. In: Desender K et al (eds) Carabid beetles: ecology and evolution, Kluwer Academic Publishers, pp 377-382

Šustek Z (1998) Biocorridors – theory and practice. In: Dover JW, Bunce RGH (eds) Key concepts in landscape ecology. IALE (UK), Preston, pp 281–296

Taboada A, Tarrega R, Calvo L, Marcos E, Marcos JA, Salgado JM (2010) Plant and carabid beetle species diversity in relation to forest type and structural heterogeneity. Eur J Forest Res 129:31–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10342-008-0245-3

Tscharntke T, Karp DS, Chaplin-Kramer R, Batáry P, De Clerck F, Gratton C, Hunt L, Ives A, Jonsson M, Larsen A, Martin EA, Martínez-Salinas A, Meehan TD, O'Rourke M, Poveda K, Rosenheim JA, Rusch A, Schellhorn N, Wanger TC, Wrattenr S, Zhang W (2016) When natural habitat fails to enhance biological pest control - Five hypotheses. Biol Conserv 204:449–458. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2016.10.001

Twardowski JP, Pastuszko K (2008) Field margins in winter wheat agrocenosis as reservoirs of beneficial ground beetles (Col. Carabidae). J Agric Eng Res 53:123–127

van Lenteren JC (2012) The state of commercial augmentative biological control: plenty of natural enemies, but a frustrating lack of uptake. Biocontrol 57:1–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10526-011-9395-1

van Lenteren JC, Bolckmans K, Köhl J, Ravensberg W, Urbaneja A (2018) Biological control using invertebrates and microorganisms: plenty of new opportunities. Biocontrol 63:39–59. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10526-017-9801-4

Wäckers FL, van Rijn PCJ, Heimpel GE (2008) Honeydew as a food source for natural enemies: Making the best of a bad meal? Biol Control 45:176–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocontrol.2008.01.007

Welling M (1990) Augmentation of beneficial insects by margin biotops. In: Materiały Konf. 6th International Symp. Pests and Deseases of Small Grain Cereals and Maize, pp 401–410

Węgorek W, Trojanowski H (1990) Epigenic entomofauna of beetles on the join of forest and field. No XXXI, Prace Naukowe IOR 2:11–48.

Wrase D. W. 2004. Harpalina. In: H. Freude, K.W. Harde, G.A. Lohse, B. Klausnitzer (eds) Die Kafer Mitteleuropas. Spektrum-Verlag Heidelberg/Berlin, 2. Auflage, pp. 344–395.

Wuczyński A, Kujawa K, Dajdok Z, Grzesiak W (2011) Species richness and composition of bird communities in various field margins of Poland. Agric Ecosyst Environ 141:202–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2011.02.031

Yu Z, Liu Y, Axmacher JC (2006) Field margins as rapidly evolving local diversity hotspots for ground beetles (Coleoptera: Carabidae) In Northern China. Coleopt Bull 60:135–143. https://doi.org/10.1649/854.1

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to Dr. Ewa Krasicka-Korczyńska for the identification of plant communities in field margin habitats, and to Dr. Grzegorz Kaczorowski for the taxonomic identification of Carabidae beetles.

Funding

The organizations that provided the funding were: Ministry of Science and Higher Education, Republic of Poland, and UTP University of Science and Technology in Bydgoszcz.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All experiments were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institution or practice at which the studies were conducted. This article does not contain any.

studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bennewicz, J., Barczak, T. Ground beetles (Carabidae) of field margin habitats. Biologia 75, 1631–1641 (2020). https://doi.org/10.2478/s11756-020-00424-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2478/s11756-020-00424-y