Abstract

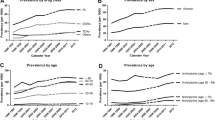

Objective: To discern population-adjusted rates of office-based physician visits in the US documenting the use of antidepressant pharmacotherapy, a diagnosis of a depressive illness, or a diagnosis of a depressive disorder in concert with the use of antidepressant pharmacotherapy.

Materials and Methods: Data from the US National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey for the time-period of 1990 through 1998 were used to discern the population-adjusted rate of office-based physician visits documenting the use of antidepressant pharmacotherapy [tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), selective serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine; 5-HT) reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) or others], a diagnosis of depression (ICD-9-CM codes 296.2 to 296.36, 300.4 or 311) or both.

Results: Office-based visits documenting the use of antidepressant pharmacotherapy for any purpose escalated from 16 534 268 in 1990 to 40 925 824 in 1998, a 147.5% increase. The number of office-based visits documenting a diagnosis of depression increased 59.1% during this period, while the proportion of office-based visits documenting a diagnosis of depression and use of antidepressant pharmacotherapy increased 31.3%. Among patients with a diagnosis of depression, use of a TCA declined from 42.1% in 1990 to 9.7% in 1998. In contrast, use of an SSRI increased from 37.1% in 1990 to 65.6% in 1998. The population-adjusted rate of office-based visits documenting the use of antidepressant pharmacotherapy for any purpose increased from 6.7 per 100 US population in 1990 to 15.1 per 100 US population in 1998, a 125.4% increase; documentation of a diagnosis of depression increased from 6.1 per 100 US population in 1990 to 8.9 per 100 US population in 1998, a 45.9% increase; and the recording of a diagnosis of depression in concert with the use of antidepressant pharmacotherapy increased from 3.2 per 100 US population in 1990 to 6.1 per 100 US population in 1998, a 90.6% increase.

Conclusion: Over the time-period 1990 to 1998, there was a significant increase in the rate of diagnosis of depressive illness in the US, and a sustained preference for use of an SSRI in the treatment of depression.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Johnson J, Weissman M, Klerman GL. Service utilization andsocial morbidity associated with depressive symptoms in thecommunity. JAMA 1992; 267: 1478–83

Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, et al. Lifetime and 12-monthprevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in theUnited States: results of the National Comorbidity Survey.Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51: 8–19

Burvill PW. Recent progress in the epidemiology of major depression.Epidemiol Rev 1995; 17: 21–31

Brugha TS, Bebbington PE. The undertreatment of depression.Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 1992; 242: 103–8

Hirschfeld RMA, Keller MB, Panico S, et al. The National Depressiveand Manic-Depressive Association consensus Statementon the undertreatment of depression. JAMA 1997; 277: 333–40

Knauper B, Wittchen HU. Diagnosing major depression in theelderly: evidence for response bias in standardized diagnosticinterviews? J Psychiatr Res 1994; 28: 147–64

Nemeroff CB. Evolutionary trends in the pharmacotherapeuticmanagement of depression. J Clin Psychiatry 1994; 55 Suppl.12: 3–15

Johnson RE, McFarland BH, Nichols GA. Changing patterns ofantidepressant use and costs in a health maintenance organization.Pharmacoeconomics 1997; 11: 274–86

DeVane CL. Pharmacokinetics of the newer antidepressants:clinical relevance. Am J Med 1994; 97 (Suppl.): 13S–23S

Sclar DA, Robison LM, Skaer TL, et al. Antidepressant pharmacotherapy: economic outcomes in a health maintenance organization. Clin Ther 1994; 16: 715–30

Skaer TL, Sclar DA, Robison LM, et al. Economic valuation ofamitriptyline, desipramine, nortriptyline, and sertraline in themanagement of patients with depression. Curr Ther Res 1995;56: 556–67

Sclar DA, Skaer TL, Robison LM, et al. Economic outcomeswith antidepressant pharmacotherapy: a retrospective intent-to-treatanalysis. J Clin Psychiatry 1998; 59 Suppl. 2: 13–17

Hylan TR, Crown WH, Meneades L, et al. Tricyclic antidepressant and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors antidepressant selection and health care costs in the naturalistic setting: a multivariate analysis. J Affect Disord 1998; 47: 71–9

Crown WH, Hylan TR, Meneades L. Antidepressant selectionand use and healthcare expenditures: an empirical approach. Pharmacoeconomics 1998; 13: 435–48

Simon GE, VonKorff M, Heiligenstein JH, et al. Initial antidepressantchoice in primary care: effectiveness and cost of fluoxetine vs tricyclic antidepressants. JAMA 1996; 275: 1897–902

Olfson M, Klerman GL. The treatment of depression: prescribingpractices of primary care physicians and psychiatrists. JFam Pract 1992; 35: 627–35

Olfson M, Klerman GL. Trends in the prescription of antidepressantsby office-based psychiatrists. Am J Psychiatry 1993;150: 571–7

Sclar DA, Skaer TL, Robison LM, et al. Trends in the prescribingof antidepressant pharmacotherapy: office-based visits 1990–1995. Clin Ther 1998; 20: 871–84

National Center for Health Statistics. 1990 summary: NationalAmbulatory Medical Care Survey, United States. Advancedata from Vital Health Stat; no. 213. Hyattsville, (MD): NationalCenter for Health Statistics; 1992

Schappert SM. National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, 1991 summary. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital HealthStat 1994; 13: 1–110

Schappert SM. National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, 1992 summary. Advance data from Vital Health Stat; no. 253. Hyattsville,(MD): National Center for Health Statistics; 1994

Woodwell DW, Schappert SM. National Ambulatory MedicalCare Survey, 1993 summary. Advance data from Vital HealthStat; no. 270. Hyattsville, (MD): National Center for HealthStatistics; 1995

Schappert SM. National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, 1994 summary. Advance data from Vital Health Stat; no. 273. Hyattsville,(MD): National Center for Health Statistics; 1996

Woodwell DA. National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, 1995 summary. Advance data from Vital Health Stat; no. 286. Hyattsville,MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 1997

Woodwell DA. National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, 1996 summary. Advance data from Vital Health Stat; no. 295. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 1997

Woodwell DA. National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, 1997 summary. Advance data from Vital Health Stat; no. 305. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 1999

Woodwell DA. National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, 1998 summary. Advance data from Vital Health Stat; no. 315. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2000

Bryant E, Shimizu I. Sampling design, sampling variance, and estimation procedures for the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat 1988; 2: 1–39

U.S. Public Health Service and Health Care Financing Administration.International classification of diseases. 9th revision:clinical modification, volume 1. DHHS publication no. (PHS) 89-1260. Washington: Public Health Service; 1989

Food and Drug Administration. National Drug Code Directory.1995 ed. Washington: Public Health Service, 1995

SETS. Statistical export and tabulation system 1.22a: users reference manual. United States Department of Health and Human Services, National Center for Health Statistics; 1991

Sclar DA, Skaer TL, Robison LM, et al. Economic appraisal of citalopram in the management of single-episode depression. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1999; 19 Suppl. 1: 47–54

U.S. Census Bureau. National population estimates forthe 1990’s: monthly postcensal resident population, by single year of age, sex, race, and Hispanic origin. Available from: URL: http://www.census.gov [Accessed 2000 Jun 30]

Skaer TL, Robison LM, Sclar DA, et al. Anxiety disorders in the United States 1990–1997: trend in complaint, diagnosis, use of pharmacotherapy, and diagnosis of comorbid depression. Clin Drug Invest 2000; 20: 255–65

Skaer TL, Robison LM, Sclar DA, et al. Psychiatric co-morbidityand pharmacologie treatment patterns among patients presenting with insomnia: an assessment of national office-based encounters 1995–1996. Clin Drug Invest 1999; 18: 161–7

Eriksson E. Serotonin reuptake inhibitors for the treatment ofpremenstrual dysphoria. Int Clin Psychoharmacol 1999; 14 Suppl 2: 27–33

Sclar DA, Robison LM, Skaer TL, et al. Ethnicity and the prescribing of antidepressant pharmacotherapy: 1992–1995. Harv Rev Psychiatry 1999; 7: 29–36

Virji A, Britten N. A study of the relationship between patients’attitudes and doctors’ prescribing. Fam Pract 1991; 8: 314–9

Bradley CP Uncomfortable prescribing decisions: a critical incidentstudy. BMJ 1992; 304: 294–6

Bradley CP. Decision making and prescribing patterns: a literaturereview. Fam Pract 1991; 8: 276–87

Bradley CP. Factors which influence the decision whether or notto prescribe: the dilemma facing general practitioners. Br JGen Pract 1992; 42: 454–8

Freiman MP, Cunningham PJ. Use of health care for the treatmentof mental problems among racial/ethnic subpopulations. Med Care Res Rev 1997; 54: 80–100

Freiman MP. The demand for healthcare among racial/ethnicsubpopulations. Health Serv Res 1998; 33: 867–90

Saha S, Komaromy M, Koepsell TD, et al. Patient-physicianracial concordance and the perceived quality and use of healthcare. Arch Intern Med 1999; 159: 997–1004

Britten N, Ukoumunne O. The influence of patients’ hopes ofreceiving a prescription on doctors’ perceptions and the decisionto prescribe: a questionnaire survey. BMJ 1997; 315: 1506–10

Himmel W, Lippert-Urbanke E, Kochen MM. Are patients moresatisfied when they receive a prescription? The effect of patientexpectations in general practice. Scand J Prim HealthCare 1997; 15: 118–22

Cockburn J, Pit S. Prescribing behavior in clinical practice:patients’ expectations and doctors’ perceptions of patients’expectations: a questionnaire study. BMJ 1997; 315: 520–3

Macfarlane J, Holmes W, Macfarlane R, et al. Influence of patients’expectations on antibiotic management of acute lowerrespiratory tract illness in general practice: questionnaire study. BMJ 1997; 315: 1211–4

Macfarlane J, Lewis SA, Macfarlane R, et al. Contemporary useof antibiotics in 1089 adults presenting with acute lower respiratorytract illness in general practice in the U.K.: implicationsfor developing management guidelines. Respir Med 1997;91: 427–34

Britten N. Patients’ demands for prescriptions in primary care. BMJ 1995; 310: 1084–5

Britten N. Patient demand for prescriptions: a view from theother side. Fam Pract 1994; 11: 62–8

Webb S, Lloyd M. Prescribing and referral in general practice:a study of patients’ expectations and doctors’ actions. Br JGen Pract 1994; 44: 165–9

Callahan CM, Dittus RS, Tierney WM. Primary care physicians’medical decision making for late-life depression. J Gen Int Med 1996; 11: 218–25

Sclar D A, Robison LM, Skaer TL, et al. What factors influencethe prescribing of antidepressant pharmacotherapy? An assessmentof national office-based encounters. Int J Psychiatry Med 1998; 28: 447–59

Simoni-Wastila L. Gender and psychotropic drug use. Med Care 1998; 36: 88–94

Williams JBW, Spitzer RL, Linzer M, et al. Gender differences in depression in primary care. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1995;173: 654–9

Melfi CA, Croghan TW, Hanna MP, Robinson RL. Racial variationin antidepressant treatment in a Medicaid population. JClin Psychiatry 2000; 61: 16–21

Sclar DA, Skaer TL, Robison LM, et al. Antidepressant prescribing patterns: a comparison of blacks and whites in a Medicaidpopulation. Clin Drug Invest 1998; 16: 135–40

Greenhalgh T, Gill P. Pressure to prescribe. BMJ 1997; 315: 1482–3

Wells KB, Burnam MA. Caring for depression in America: lessonslearned from early findings of the medical outcomesstudy. Psychiatr Med 1991; 9: 503–19

Cooper-Patrick L, Gallo JJ, Powe NR, et al. Mental health service utilization by African Americans and whites: the BaltimoreEpidemiologic Catchment Follow-Up. Med Care 1999; 37: 1034–45

Brown C, Schulberg HC, Sacco D, et al. Effectiveness of treatments for major depression in primary medical care practice: a post hoc analysis of outcomes for African American andwhite patients. J Affect Disord 1999; 53: 185–92

Crisp AH, Gelder MG, Rix S, et al. Stigmatisation of peoplewith mental illness. Br J Psychiatry 2000; 177: 4–7

Munitz H, Valevski A, Weizman A, et al. Recognition and treatmentof depression in primary care settings in six differentcountries: a retrospective file analysis by the WHO. EuropeanJ Psychiatry 2000; 14: 85–93

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Pharmacoeconomics and Pharmacoepidemiology Research Unit, College of Pharmacy, Washington State University, USA.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Skaer, T.L., Sclar, D.A., Robison, L.M. et al. Trend in the Use of Antidepressant Pharmacotherapy and Diagnosis of Depression in the US. CNS Drugs 14, 473–481 (2000). https://doi.org/10.2165/00023210-200014060-00005

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/00023210-200014060-00005