Abstract

Objective: Recent data indicate that the combination of a low cholesterol diet and simvastatin following heart transplantation is associated with significant reduction of serum cholesterol levels, lower incidence of graft vessel disease (GVD) and significantly superior 4-year survival rates than dietary treatment alone. On the basis of this first randomised long term study evaluating survival as the clinical end-point, we investigated the cost effectiveness of the above regimens as well as the long term consequences for the patient and for heart transplantation as a high-tech procedure.

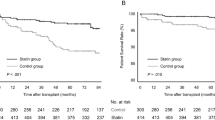

Design and setting: The perspective of the economic analysis was that of the German health insurance fund. Life-years gained were calculated on the basis of the Kaplan-Meier survival curves from the 4-year clinical trial and from the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT) overall survival statistics. Incremental costs and incremental cost-effectiveness ratios were determined using various sources of data, and both costs and consequences were discounted by 3% per year. Sensitivity analyses using alternative assumptions were conducted in addition to the base-case analysis.

Patients and participants: As in the original clinical trial, the target population of the economic evaluation comprised all heart transplant recipients on standard triple immunosuppression consisting of cyclosporin, azathioprine and prednisolone, regardless of the postoperative serum lipid profile.

Interventions: The therapeutic regimens investigated in the analysis were the American Heart Association (AHA) step II diet plus simvastatin (titrated to a maximum dosage of 20 mg/day) and AHA step II diet alone.

Main outcome measures and results: Four years of treatment with simvastatin (mean dosage 8.11 mg/day) translated into an undiscounted survival benefit per patient of 2.27 life-years; 0.64 life-years within the trial period and 1.63 life-years thereafter. Discounted costs per year of life gained were $US1050 (sensitivity analyses $US800 to $US15 400) for simvastatin plus diet versus diet alone and $US18 010 (sensitivity analyses $US17 130 to $US21 090) for heart transplantation plus simvastatin versus no transplantation (all costs reflect 1997 values; $US1 = 1.747 Deutschmarks).

Conclusions: Prevention of GVD with simvastatin after heart transplantation was cost effective in all the scenarios examined with impressive prolongation of life expectancy for the heart recipient. Simvastatin also achieved an internationally robust 21% improvement in the cost effectiveness of heart transplantation compared with historical cost-effectiveness data.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

ISHLT 14th Annual Data Report. Available from: URL: (http://www.richmond.infi.net/~ishlt/ishlt_97/cause.html#heart_lung) [accessed 1997 Jul 8]

Eich D, Thompson JA, Ko DJ, et al. Hypercholesterolemia in long-term survivors of heart transplantation: an early marker of accelerated coronary artery disease. J Heart Lung Transplant 1991; 10: 45–9

Sharples LD, Caine N, Mullins P, et al. Risk factor analysis for the major hazards following heart transplantation: rejection, infection, and coronary occlusive disease. Transplantation 1991; 52: 244–52

Ballantyne CM, Radovancevic B, Farmer JA, et al. Hyperlipidemia after heart transplantation: report of a 6-year experience, with treatment recommendations. J Am Coll Cardiol 1992; 19 (6): 1315–21

Schröder JS, Gao SZ, Alderman EL, et al. A preliminary study of diltiazem in the prevention of coronary artery disease in heart-transplant recipients. N Engl J Med 1993; 328 (3): 164–70

Hidalgo L, Zambrana JL, Blanco-Molina A, et al. Lovastatin versus bezafibrate for hyperlipemia treatment after heart transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant 1995; 14 (3): 461–7

Barbir M, Hunt B, Kushwaha S, et al. Maxepa versus bezafibrate in hyperlipidemic cardiac transplant recipients. Am J Cardiol 1992; 70: 1596–601

Kobashigawa JA, Katznelson S, Laks H, et al. Effects of pravastatin on outcomes after cardiac transplantation. N Engl J Med 1995; 33: 621–7

Wenke K, Meiser B, Thiery J, et al. Simvastatin reduces graft vessel disease and mortality after heart transplantation: a fouryear randomized trial. Circulation 1997; 96 (5): 1398–402

Ballantyne C, Bourge RC, Domalik LJ, et al. Treatment of hyperlipidemia after heart transplantation and rationale for the heart transplant registry. Am J Cardiol 1996; 78: 532–5

Christopherson LK. Organ transplantation and artificial organs. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 1986; 2: 553–62

Evans RW. Organ transplantation and the inevitable debate as to what constitutes a basic health care benefit. In: Terasaki PI, Cecka JM, editors. Los Angeles (CA): UCLA Tissue Typing Laboratory, 1993: 359–91

Gold MR, Russell LB, Soegel JE, et al., editors. Cost-effectiveness in health and medicine. New York (NY): Oxford University Press, 1996

ISHLT 14th Annual Data Report. Available from: URL: http://www.richmond.infi.net/~~ishlt/registry/survival.htm#surv_a1 [accessed 1996 Nov 21]

Rote Liste 1997. Editio Cantor Verlag für Medizin und Naturwissenschaften GmbH. Aulendorf/Württemberg: ECV, 1997

GOÄ und BG-GOÄ. Gebührenordnung für Ärzte (GOÄ). 8. Auflage. Dachau: Zauner Druck und Verlags GmbH, 1997

Haberman S. Heart transplants: putting a price on life. Health Soc Serv J 1982; 90: 877–9

Pennock JL, Oyer PE, Reitz BA, et al. Cardiac transplantation in perspective for the future: survival, complications, rehabilitation & cost. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1982; 83: 168–77

ISHLT 14th Annual Data Report. Available from: URL: http://www.richmond.infi.net/~ishlt/ishlt_97/surv_1.html#overall [accessed 1997 Jul 15]

Scheld HH, Deng MC, Hammel D, et al. Kosten/Nutzen-Relation der Herztransplantation. Z Kardiol 1994; 83 Suppl. 6: 139–49

The CONSENSUS Trial Study Group. Effects of enalapril on mortality in severe congestive heart failure: results of the cooperative north scandinavian survival study. N Engl J Med 1987; 316: 1429–35

van Hout B, Bonsel G, Habbema D, et al. Heart transplantation in the Netherlands: costs, effects and scenarios. J Health Econ 1993; 12: 73–93

Lee E. Statistical methods for survival data analysis. Belmont (CA): Wadsworth Inc., 1980: 162–7

1997 Drug Topics Red Book. Montvale (NJ): Medical Economics Company, Inc., 1997

The artificial heart: prototypes, policies, and patients. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press, 1992: 268–9

Sharples LD, Briggs A, Caine N, et al. A model for analyzing the cost of main clinical events after cardiac transplantation. Transplantation 1996; 62 (5): 615–21

Ammerman AS, Devellis RF, Keyserling TC, et al. Quality of life is not adversely affected by a dietary intervention to reduce cholesterol [abstract]. Circulation 1993; 87: 19

Lawrence WF, Fryback DG, Martin PA. Cholesterol and health status in the Beaver Dam Health Outcomes Study [abstract]. Med Decis Making 1994; 14: 436

Zimmermann R, Haverich A. Herztransplantation [editorial]. Fortschr Kardiol 1996; 1: 22

Anhang 1 (zu Artikel 1 Nr. 3) der Dritten Verordnung zur Änderung der Bundespflegesatzverordnung. Bundesgesetzblatt (BGBl.) I, Nr 68 vom 28. Köln: Bundesanzeiger Verlagsges mbH, 1995: 2006–12

Statistisches Bundesamt. Statistisches Jahrbuch für die Bundesrepublik Deutschland. Wiesbaden: Statistisches Bundesamt, 1997

United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS). UNOS OPTN/Scientific Registry data. Richmond (VA): UNOS, 1997

Hauboldt RH. Cost implications of human organ transplantations: an update. Brookfield (CT): Milliman and Robertson, Inc., 1993

Poirier VL. The economic burden of artificial hearts: progress in artificial organs. Cleveland (OH): ISAO Press, 1986: 96–9

Discounting health care: only a matter of timing? Lancet 1992; 340: 148–9

Smith PE, Eydelloth RS, Grossman SJ, et al. HMG-CoA-Reductase inhibitor induced myopathy in the rat: cyclosporine interaction and mechanism studies. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1991; 257: 1225–30

Mauro VF. Clinical pharmacokinetics and practical applications of simvastatin. Clin Pharmacokinet 1993; 24: 195–202

The Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study Group. Randomized trial of cholesterol lowering in 4444 patients with coronary artery disease: the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S). Lancet 1994; 344: 1383–9

Jönsson B, Johannesson M, Kjekshus J, et al. Cost-effectiveness of cholesterol lowering. Eur Heart J 1996; 17: 1001–7

Malik IS, Anderson MH. Cost-efficacy of cholesterol lowering: West of Scotland Coronary Prevention Study versus the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study [abstract]. Heart 1996; 75 Suppl. 1: 77

European Transplant Coordinators Organization (ETCO) Statistics. Available from: URL: http://www.kuleuven.ac.be [accessed 1997 Jul 8]

Shepherd J, Cobbe SM, Ford I, et al. Prevention of coronary heart disease with pravastatin in men with hypercholesterolemia. N Engl J Med 1995; 333 (20): 1301–7

Institute of Medicine (IOM). National priorities for the assessment of clinical conditions and medical technologies. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press, 1990

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Krobot, K.J., Wenke, K. & Reichart, B. Simvastatin After Orthotopic Heart Transplantation. Pharmacoeconomics 15, 279–289 (1999). https://doi.org/10.2165/00019053-199915030-00007

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/00019053-199915030-00007