Abstract

Synopsis

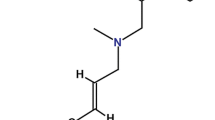

Terbinafine is an orally and topically active allylamine antifungal drug which is an effective and well tolerated therapy for a wide range of superficial dermatophyte infections. In contrast to most other commonly prescribed antifungal agents, terbinafine is fungicidal in vitro and possesses improved pharmacokinetic properties with respect to drug penetration into nail tissue following oral administration. These properties enable terbinafine to achieve high success rates with shortened therapy regimens in the treatment of dermatophyte skin infections and onychomycosis.

Pharmacoeconomic analyses have shown that oral terbinafine, with its higher rates of clinical efficacy and lower rates of relapse/reinfection, is less costly and more cost effective than oral griseofulvin, ketoconazole and itraconazole when used as initial therapy in the treatment of onychomycosis. However, some points regarding the clinical efficacy of itraconazole relative to terbinafine and the drug treatment regimens used in these studies need further clarification.

In the management of tinea pedis, a cost analysis suggested that initial therapy with terbinafine 1% cream was more costly than initial therapy with miconazole, oxiconazole or clotrimazole. However, in cost-effectiveness studies, terbinafine had a lower cost per disease-free day than ciclopirox, clotrimalzole, ketoconazole and miconazole in the treatment of dermatophyte skin infections.

In conclusion, available clinical and pharmacoeconomic data support the use of topical terbinafine as first-line treatment of dermatophyte skin infections unless the acquisition cost of terbinafine is markedly greater, than that of alternative topical antifungal agents. Oral terbinafine can be recommended as a cost-effective first-line treatment, preferable to oral griseofulvin, ketoconazole and itraconazole, in patients with dermatophyte onychomycosis.

Disease and Treatment Considerations

Superficial fungal infections caused by detmatophyte fungi are prevalent in the general population and have been called the most common infectious disease. These infections can be disfiguring and painful and can adversely impact on quality of life (most notably in patients with onychomycosis). They are associated with substantial treatment costs.

Detmatophytoses such as tinea pedis. tinea cruris and tinea corporis typically respond to treatment with topical antifungal agents (e.g. miconazole, tolnaftate. clotrimazole, naftifine and ketoconazole) applied twice daily for up to 4 weeks. with efficacy rates generally >80%. However, noncompliance with full treatment courses is common. Extensive or recalcitrant dennatophyte infections such as onychomycosis and severe forms of tinea pedis (e.g. plantar- or moccasin-type tinea pedis) require therapy with oral antifungal drugs.

Terbinafine is an orally and topically active allylamine antifungal drug. In contrast to the in vitro fungistatic activities of griseofulvin, ketoconazole, itraconazole and most other antifungal drugs, terbinafine is fungicidal in vitro. It also penetrates well into nails, maintaining high concentrations for at least 55 days after discontinuation of oral therapy which allows for continued clinical resolution of infection even after the completion of a course of treatment. These properties enable terbinafine to achieve high efficacy rates in the treatment of superficial fungal infections, even with shortened treatment regimens.

In the treatment of dennatophyte nail infections, clinical trials have shown that oral terbinafine (250 mg/day for 12 to 24 weeks) is effective and well tolerated, producing success rates (both clinical and mycological cure) in approximately 80 and 95% of patients, respectively, with toenail and fingernail mycoses. In recent comparative trials, terbinafine 250 mg/day for 12 and 16 weeks. respectively, achieved significantly higher success rates than griseofulvin 500 mg/day for 12 weeks (76 vs 39%) in the treatment of fingernail dermatophyte infections and imennittent itraconazole 400 mg/day for 1 of 4 weeks for 16 weeks (76 vs 35%) in the treatment of toenail and fingernail dermatophyte infections.

Oral terbinafine has also demonstrated good clinical and mycological efficacy in the treatment of tinea pedis. including more extensive infections (e.g. plantar-type tinea pedis). Rates of mycological cure with 2 weeks’ treatment with terbinafine 250 mg/day (range 78 to 89%) were similar to those with 4 weeks’ treatment with itraconazole 100 mg/day (69 to 81%), and were significantly higher than 2 weeks’ treatment with itraconazole 100 mg/day (86 vs 55%). Treatment relapses appeared to be less frequent in terbinafine recipients.

In patients with dermatophyte skin infections, terbinafine 1 % cream administered for 2 to 4 weeks produces mycological cure and clinical efficacy rates of 93% and approximately 80%, respectively. Similar cure r ates have been achieved with treatment periods of 1 to 2 weeks. Furthermore, in 2 recent comparative trials, a 1-week course of terbinafine 1 % cream produced higher mycological cure rates than a 4-week course of clotrimazole 1 % cream (97 vs 84% at 6 weeks in 1 study and 83 vs 66% at 12 weeks in the other) in patients with tinea pedis.

Pharmacoeconomic Evaluation

The pharmacoeconomics of oral terbinafine in the treatment of onychomycosis have been assessed in payer-perspective studies. Projected costs of oral terbinafine therapy and disease management (with all patients being treated with terbinafine by their general practitioners) were about half of those associated with treatment with griseofulvin in patients referred to a dermatology clinic in a UK cost analysis. This difference was due to the lower physician costs (avoidance of further dermatology clinic disease management) as well as lower drug costs for retreatment due to relapse/reinfection. In a 13-country cost-effectiveness study, which used a decision analysis model to outline all possible treatment outcomes, terbinafine was more cost effective (lower cost per disease-free day) than griseofulvin, ketoconazole and itraconazole in the treatment of both fingernail and toenail onychomycosis. Data from 3 countries (Canada, Germany and The Netherlands) included in this analysis were published separately and were generally consistent with the overall results from the 13-country study. The usefulness of these data are somewhat limited by the fact that the duration, dosage and type of antifungal drug regimens used in the decision analysis model were not clearly stated. Some points regarding the clinical effectiveness of itraconazole relative to terbinafine also require further clarification.

Three studies (1 cost analysis and 2 cost-effectiveness studies) evaluated the pharmacoeconomics of terbinafine 1 % cream in the topical treatment of dermatophyte skin infections. The cost analysis was performed from a purchaser’s perspective and indicated that the initial use of terbinafine for topical therapy of tinea pedis was more costly than initial topical treatment with miconazole, oxiconazole or clotrimazole (even after taking treatment failures with these agents and subsequent treatment with topical terbinafine into consideration). However, 2 cost-effectiveness studies, which used a similar decision analysis model to that described in the 13-country study above, showed that topical terbinafine was more cost effective and produced more disease-free days than topical ciclopirox, clotrimazole, ketoconazole or miconazole in the treatment of dermatophyte skin infections. It is important to note that these cost-effectiveness data (from Canada, Germany, Switzerland and Austria) do not necessarily extrapolate to other countries.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Jones HE. Therapy of superficial Fungal infections. Med Clin North Am 1982; 66: 873–93

Siern RS. The epidemiology of cutaneous disease. In: Fitzpatrick TB. Eisen AZ, Wolff K, et al., editors. Dermatology in general practice. New York: McGraw Hill, 1993: 7–13

Prevalence, morbidity, and cost of dermatologies] diseases. J Invest Dermatol 1979; 75: 395–401

Infections. J Invest Dermatol 1979; 73: 452–9

Evans EG, Dodman B, Williamson DM, et al. Comparison of terbinafine and clotrimazole in treating tinea pedis. BMJ 1993 Sep 11: 307: 645–7

Midgley G, Moore MK, Cook JC, et al. Mycology of nail disorders. J Am Acad Dermatol 1994; 31Suppl.: S68–74

André J, Achten G. Onychomycosis. Int J Dermatol 1987; 26: 481–90

Hay RJ, Roberts SOB, Mackenzie DWR. Mycology. In: Champion RH, Burton JL. Ebling FJG, editors. Textbook of dermatology. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific Publications, 1992: 1158–9

Summerbell RC, Kane J, Krajden S. Onychomycosis, tinea pedis and tinea manuum caused by non-dermatophytic filamentous fungi. Mycoses 1989; 32: 609–19

Roberts DT. Prevalence of dermatophyte onychomycosis in the United Kingdom: results of an omnibus survey. Br J Dermatol 1992; 126Suppl, 39: 23–7

Dompmartin D, Dompmartin A, Deluol AM. et al. Onychomycosis and AIDS. Clinical and laboratory findings in 62 patients. Int J Dermatol 1990; 29: 337–9

Staughton R. Skin manifestations in AIDS patients. Br J Clin Pract 1990; 71Suppl.: 109–13

Rosenbach ML, Schneider JE. The burden of onychomycosis in the Medicare population. Health Economic Research Inc., Waltham, Massachusetts, USA, Sandoz Pharmaceuticals Corporation data on file, 1992

Hay RJ. Antifungal drugs in dermatology. Semin Dermatol 1990; 9: 309–17

Hay RJ. Treatment of dermatomycoses and onychomycoses - state of the art. Clin Exp Dermatol 1992; 17 Suppl. 1: 2–5

Meinhof W, Gerardi RM, Straeke A. Patient non-compliance in dermatomycosis: results of a survey among dermatologists and general practitioners and patients. Dermatologica 1984; 19Suppl. 1: 57–66

Korting HC, Schäfer-Korting M. Is tinea unguium still widely incurable? A review three decades after the introduction of griseofulvin. Arch Dermatol 1992 Feb: 128: 243–8

Hay RJ, Clayton YM, Griffiths M, et al. A comparative double blind study of ketoconazole and griseofulvin in dermatophytosis. Br J Dermatol 1985; 112: 691–6

Robertson MH, Hanifin JM, Parker F. Oral therapy with ketoconazole for dermatophyte infections unresponsive to griseofulvin. Rev Infect Dis 1980; 2: 578–81

Svejgaard E. Oral ketoconazole as an alternative to griseofulvin in recalcitrant dermatophyte infections and onychomycosis. Acta Derm Venereol 1985: 65: 143–9

Galimberti R, Negroni R, de Elias MRI, et al. The activity of ketoconazole in the treatment of onychomycosis. Rev Infect Dis 1980: 2: 596–8

Heiberg JK, Svejgaard E. Toxic hepatitis during ketoconazole treatment. BMJ 1981: 283: 825–6

Lewis JH, Zimmerman HJ, Benson GD, et al. Hepatic injury associated with ketoconazole therapy: analysis of 33 cases. Gastroenterology 1984; 86: 503–13

Boughton K. Ketoconazole and hepatic reactions [letter]. S Afr Med J 1983: 63: 955

Hay RJ, Clayton YM, Moore MK. A comparison of tioconazole 28% solution versus base as an adjunct to oral griseofulvin in patients with onychomycosis. Clin Exp Dermatol 1987; 12: 175–7

Lauharanla J, Zaug M, Polak A, et al. Combination of amorolfine with griseofulvin: in vitro activity and clinical results in onychomycosis. JAMA Southeast Asia 1993; 9Suppl. 4: 23–7

Hay RJ, Clayton YM, Moore MK, et al. An evaluation of itraconazole in the management of onychomycosis. Br J Dermatol 1988; 119: 359–66

Walsoe I, Strangerup M, Svejgaard E. Itraconazole in onychomycosis: open and double-blind studies. Acta Derm Venereol 1990; 70: 137–40

Korting HC, Schäfer-Korting M, Zienicke H, et al. Treatment of tinea unguium with medium and high doses of ultramicrosize griseofulvin compared with that with itraconazole. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1993; 37: 2064–8

Willemsen M, De Doncker P, Willems J, et al. Posttreatment itraconazole levels in the nail: new implications for treatment of onychomycosis. J Am Acad Dermatol 1992; 26: 731–5

Piepponen T, Blomqvist K, Brandt H, et al. Efficacy and safety of itraconazole in the long-term treatment of onychomycosis. J Antimicrob Chemother 1992; 29: 195–205

Saag MS, Dismukes WE. Azole antifungal agents: emphasis on new triazoles. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1988; 32: 1–8

Grant SM, Clissold SP. Itraconazole: a review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties, and therapeutic use in superficial and systemic mycoses. Drugs 1989; 37: 310–44

Roberts DT. Itraconazole in dermatology. J Dermatol Treat 1992; 2: 155–8

Stary A, Torma S, Storch M, et al. Itraconazole in the management of onychomycosis; longterm observations with two different treatment schedules [abstract]. Presented at the International Summit on Cutaneous Antifungal Therapy; 1994 Nov 10-13; Boston.

Ginter G. Intermittent therapy with itraconazole - a new approach to the treatment of onychomycosis. Presented at the International Summit on Cutaneous Antifungal Therapy; 1994 Nov 10-13; Boston.

Balfour JA, Faulds D. Terbinafine: a review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties, and therapeutic potential in superficial mycoses [published erratum appears in Drugs 1992 May; 43 (5): 699], Drugs 1992 Feb; 43: 259–84

Cleary JD, Taylor JW, Chapman SW. Imidazoles and triazoles in antifungal therapy. DICP 1990; 24: 148–51

Sud IJ, Feingold DS. Mechanisms of action of the antimycotic imidazoles. J Invest Dermatol 1981; 76: 438–41

Ryder NS. The mechanism of action of terbinafine. Clin Exp Dermatol 1989; 14: 98–100

Petranyi G, Ryder NS, Stulz A. Allylamine derivatives: new class of synthetic antifungal agents inhibiting fungal squalene epoxidase. Science 1984 Jun 15; 224: 1239–41

Ryder NS, Mieth H. Allylamine antifungal drugs. Curr Top Med Mycol 1992; 4: 158–88

Clayton YM. Relevance of broad-spectrum and fungicidal activity of antifungals in the treatment of dermatomycoses. Br J Dermatol 1994; 130Suppl. 43: 7–8

Zebender H, Cabiac MD, Denouël J, el at. Elimination kinetics of terbinafine from human plasma and tissues following multiple-dose administration, and comparison with 3 main metabolites. Drug Invest 1994; 8: 203–10

Faergemann J, Zehender H, Denouël J, et al. Levels of terbinafine in plasma, stratum corneum, dermis-epidermis (without stratum corneum), sebum, hair and nails during and after 250 mg terbinafine orally once per day for four weeks. Acta Derm Venereol 1993; 73: 305–9

Breckenridge A. Clinical significance of interactions with antifungal agents. Br J Dermatol 1992: 126Suppl. 39: 19–22

Back DJ, Tjia JF, Abel SM. Azoles, allyamines and drug metabolism. Br J Dermatol 1992; 126Suppl. 39; 14–8

Back DJ, Tjia JF. Azoles and allylamines: the clinical implications of interaction with cytochrome P-450 enzymes. J Dermatol Treat 1990; 1Suppl. 2: 11–3

Janssen Pharmaceutica. Ketoconazole prescribing information. Physicians’ Desk Reference, Titusville, New Jersey, USA, 1994

Janssen Pharmaceutica. Itraconazole prescribing information. Physicians’ Desk Reference, Tilusville, New Jersey, USA, 1994

Strieker BH, Ottervanger JP. Recording of possible side effects in the Bureau for Side Effects of Drugs and research activities in 1992 [in Dutch]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 1993; 137: 1784–7

Ottervanger JP, Strieker BH. Loss of taste and terbinafine [letter]. Lancet 1992: 339: 1483

Juhlin L. Loss of taste and terbinafine [letter]. Lancet 1992; 339: 1483

Beutler M, Hartmann K, Kuhn M, et al. Taste disorders and terbinafine [letter]. BMJ 1993; 307: 26

Lowe G, Green C, Jennings P. Hepatitis associated with terbinafine treatment [letter]. BMJ 1993; 306: 248

Roberts DT. Oral therapeutic agents in fungal nail disease. J Am Acad Dermatol 1994; 31Suppl.: S78–81

Finlay AY. Global overview of Lamisil. Br J Dermatol 1994 Apr, 130Suppl. 43: 1–3

Baudraz-Rosselet F, Rakosi T, Wili PB, et al. Treatment of onychomycosis with terbinafine. Br J Dermatol 1992 Feb; 126Suppl. 39: 40–6

Zaias N. Management of onychomycosis with oral terbinafine. J Am Acad Dermatol 1990 Oct; 23(4 Pt 2): 810–2

van-der-Schroeff JG, Cirkel PKG, Crijns MB, et al. A randomized treatment duration-finding study of terbinafine in onychomycosis. Br J Dermatol 1992 Feb: 126Suppl. 39: 36–9

Goodfield MJ, Andrew L, Evans EGV. Short term treatment of dermatophyte onychomycosis with terbinafine. BMJ 1992 May 2; 304: 1151–4

Haneke E, Tausch I, Bräutigam M, et al. Short-duration treatment of fingernail dermatophytosis: a randomized, double-blind study with terbinafine and griseofulvin. J Am Acad Dermatol 1995; 32: 72–7

Rakosi T. Terbinafine and onychomycosis. Dermatologies 1990; 181: 74

Arikian SR, Einarson TR, Kobelt-Nguyen G, et al. A multinational Pharmacoeconomic analysis of oral therapies for onychomycosis. The Onychomycosis Study Group. Br J Dermatol 1994 Apr; 130Suppl. 43: 35–44

Shear NH, Villars VV, Marsolais C. Terbinafine: an oral and topical antifungal agent. Clin Dermatol 1992 Oct-Dec; 9: 487–95

Villars VV, Jones TC. Special features of the clinical use of oral terbinafine in the treatment of fungal diseases. Br J Dermatol 1992 Feb; 126Suppl. 39: 61–9

Drake LA, Shear NH, Arletta JP, et al. Oral terbinafine (Lamisil) in the treatment of toenail onychomycosis: a North American multicenter study [abstract]. Presented at the American Academy of Dermatology Meeting; 1995 Feb 4-9, New Orleans.

Tosli A, Stinchi C, Morelli R, et al. Terbinafine versus itraconazole in the treatment of dermatophyte nail infections. Presented at the International Summit on Cutaneous Antifungal Therapy; 1994 Nov 10-13; Boston.

Davies RR, Everall JD, Hamilton E. Mycological and clinical evaluation of griseofulvin for chronic onychomycosis. BMJ 1967; 2: 464–8

Hay RJ, McGregor JM, Wuite J, et al. A comparison of 2 weeks of terbinafine 250 mg/day with 4 weeks of itraconazole 100 mg/day in planlar-type tinea pedis. Br J Dermatol 1995; 132: 604–8

Kim K-H, Choi JS, Park ES, et al. Multicenter, double-blind, comparative study of the efficacy and safely of terbinafine 250 mg/day for 4 weeks in the treatment of patients with tinea pedis. J Korean Soc Chemother 1994, 12: 162–72

Voravutinon V. Double-blind comparative study of the efficacy and tolerability of terbinafine with itraconazole in patients with tinea pedis. Songkla Med J 1993; 11: 149–53

De Keyser P, De Backer M, Massart DL, et al. Two-week oral treatment of tinea pedis, comparing terbinafine (250 mg/day) with itraconazole (100 mg/day): a double-blind, multicentre study. Br J Dermatol 1994: 130Suppl. 43: 22–5

Berman B, Ellis C, Leyden J, et al. Efficacy of a 1-week, twice-daily regimen of terbinafine 1% cream in the treatment of interdigital tinea pedis: results of placebo-controlled, double-blind, multicenter trials. J Am Acad Dermatol 1992 Jun; 26: 956–60

Evans EGV, James IGV, Joshipura RC. Two-week treatment of tinea pedis with terbinafine (Lamisil) 1% cream: a placebo controlled study. J Dermatol Treat 1991; 2: 95–7

Evans EGV, Shah JM, Joshipura RC. One-week treatment of tinea corporis and tinea cruris with terbinafine (Lamisil) 1% cream: a placebo-controlled study. J Dermatol Treat 1992; 3: 181–4

Cordero C, de la Rosa I, Espinoza Z, et al. Short-term therapy of tinea cruris/corporis with topical terbinafine. J Dermatol Treat 1992; 3Suppl. 1: 23–4

Zaias N, Berman B, Cordero CN, et al. Efficacy of a 1-week, once-daily regimen of terbinafine 1% cream in the treatment of tinea cruris and tinea corporis. J Am Acad Dermatol 1993; 29: 646–8

Elewski B, Bergstresser PR, Hanifin J, et al. Long-term outcome of patients with interdigital tinea pedis treated with terbinafine or clotrimazole. J Am Acad Dermatol 1995; 32: 290–2

Evans EGV, Seaman RAJ, James IGV. Short-duration therapy with terbinafine 1% cream in dermatophyte skin infections. Br J Dermatol 1994 Jan; 130: 83–7

Page JC, Abramson C, Lee W-L, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of tinea pedis: a review and update. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc 1991; 81: 304–16

Scher RK. Onychomycosis is more than a cosmetic problem. Br J Dermatol 1994 Apr: 130Suppl. 43: 15

Lubeck DP, Patrick DL, McNulty P, et al. Quality of life of persons with onychomycosis. Qual Life Res 1993 Oct; 2: 341–8

Goodfield MJD, Bosanquet N, Evans EGV, et al. Cost effective clinical management of onychomycosis. Br J Med Econ 1994; 7: 15–23

Einarson TR, Arikian SR, Shear NH. Cost-effectiveness analysis for onychomycosis therapy in Canada from a government perspective. Br J Dermatol 1994 Apr; 130Suppl. 43: 32–4

Kobelt-Nguyen G, van Assche D. Mycosis of finger and toe nails: pharmacoeconomic analysis of oral treatment in Germany [in German]. Z Allgemeinmed 1994 Sep 5; 70: 683–5

Bergman W, Rutten FFH. Cost-effectiveness of griseofulvin, itraconazole, ketoconazole and terbinafine in the oral treatment of onychomycosis of the toenail [in Dutch]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 1994: 138: 2346–50

Chren M-M, Landefeld CS. A cost analysis of topical drug regimens for dermatophyte infections. JAMA 1994 Dec 28; 272: 1922–5

Shear NH, Einarson TR, Arikian SR, et al. Pharmacoeconomic analysis of topical treatments for tinea infections. PharmacoEconomics 1995; 7: 251–67

Shear NH, Einarson TR, Arikian SR, et al. Pharmacoeconomic analysis of topical treatments for tinea infections: a comparative analysis in Austria, Germany and Switzerland [in German]. Z Allgemeinmed 1995; 71: 1055–60

Finlay AY. Pharmacokinetics of terbinafine in the nail. Br J Dermatol 1992 Feb; 126Suppl. 39: 28–32

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Various sections of the manuscript reviewed by: S. R. Arikian, Center of Health Outcomes and Economics, East Brunswick, New Jersey, USA; F. Baudraz-Rosselet, Department of Dermatology, University Hospital of Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland; M-M. Chren, Department of Dermatology, Cleveland Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Cleveland, Ohio, USA; Y.M. Clayton, St. John’s Institute of Dermatology, Department of Medical Mycology, St. Thomas’ Hospital, London, England; H. Degreef, Department of Dermatology, Universitaire Ziekenhuizen Leuven, Leuven, Belgium; A. Y. Finlay, Department of Dermatology; University of Wales College of Medicine, Cardiff, Wales; M.J.D. Goodfield, Department of Dermatology, The General Infirmary at Leeds, Leeds, England; E. Haneke, Department of Dermatology, Ferdinand-Sauerbruch-Hospital, Wupperta l, Germany; H.C. Korting, Department of Dermatology, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universitat, Munich, Germany; D.P. Lubeck, Division of Immunology and Rheumatology, Stanford University School of Medicine, Palo Alto, California, USA; G.E. Piérard, Department of Dermopathology, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Liège, Liège, Belgium; N.H. Shear, Departments of Medicine and Pharmacology, Sunnybrook Health Service Center, North York, Ontario, Canada; J.G. van der Schroeff, Department of Dermatology, Bronovo Hospital. Den Haag, The Netherlands.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Davis, R., Balfour, J.A. Terbinafine. Pharmacoeconomics 8, 253–269 (1995). https://doi.org/10.2165/00019053-199508030-00008

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/00019053-199508030-00008