Abstract

Hyperuricaemia occurs in 5–84% and gout in 1.7–28% of recipients of solid organ transplants. Gout may be severe and crippling, and may hinder the improved quality of life gained through organ transplantation. Risk factors for gout in the general population include hyperuricaemia, obesity, weight gain, hypertension and diuretic use. In transplant recipients, therapy with ciclosporin (cyclosporin) is an additional risk factor.

Hyperuricaemia is recognised as an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease; however, whether anti-hyperuricaemic therapy reduces cardiovascular events remains to be determined.

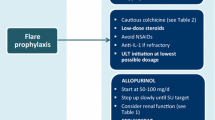

Dietary advice is important in the management of gout and patients should be educated to partake in a low-calorie diet with moderate carbohydrate restriction and increased proportional intake of protein and unsaturated fat. While gout is curable, its pharmacological management in transplant recipients is complicated by the risk of adverse effects and potentially severe interactions between immunosuppressive and hypouricaemic drugs. NSAIDs, colchicine and corticosteroids may be used to treat acute gouty attacks. NSAIDs have effects on renal haemodynamics, and must be used with caution and with close monitoring of renal function. Colchicine myotoxicty is of particular concern in transplant recipients with renal impairment or when used in combination with ciclosporin. Long-term urate-lowering therapy is required to promote dissolution of uric acid crystals, thereby preventing recurrent attacks of gout. Allopurinol should be used with caution because of its interaction with azathioprine, which results in bone marrow suppression. Substitution of mycophenylate mofetil for azathioprine avoids this interaction. Uricosuric agents, such as probenecid, are ineffective in patients with renal impairment. The exception is benzbromarone, which is effective in those with a creatinine clearance >25 mL/min. Benzbromarone is indicated in allopurinol-intolerant patients with renal failure, solid organ transplant or tophaceous/ polyarticular gout. Monitoring for hepatotoxicty is essential for patients taking benzbromarone.

Physicians should carefully consider therapeutic options for the management of hypertension and hyperlipidaemia, which are common in transplant recipients. While loop and thiazide diuretics increase serum urate, amlodipine and losartan have the same antihypertensive effect with the additional benefit of lowering serum urate. Atorvastatin, but not simvastatin, may lower uric acid, and while fenofibrate may reduce serum urate it has been associated with a decline in renal function.

Gout in solid organ transplantation is an increasing and challenging clinical problem; it impacts adversely on patients’ quality of life. Recognition and, if possible, alleviation of risk factors, prompt treatment of acute attacks and early introduction of hypouricaemic therapy with careful monitoring are the keys to successful management.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Schlesinger N. Management of acute and chronic gouty arthritis: present state-of-the-art. Drugs 2004; 64(21): 2399–416

Delaney N, Summrani N, Daskalakis P, et al. Hyperuricaemia and gout in renal allograft recipients. Transplant Proc 1992; 24(5): 1773–4

Schlesinger N, Schumacher HR. Gout: can management be improved? Curr Opin Rheumatol 2001; 13: 240–4

Roubenoff R, Klag M, Mead L, et al. Incidence and risk factors for gout in white men. JAMA 1991; 266(21): 3004–7

Choi H, Atkinson K, Karlson E, et al. Obesity, weight change, hypertension, diuretic use and risk of gout in men. Arch Intern Med 2005; 165(7): 742–8

Lin K-C, Lin H–Y, Chou P. The interaction between uric acid level and other risk factors on the development of gout among asymptomatic hyperuricaemic men in a prospective study. J Rheumatol 2000; 27(6): 1501–5

Fam A. Gout, diet and the insulin resistance syndrome. J Rheumatol 2002; 29(7): 1350–5

Vazquez-Mellado J, Garcia C, Vazquez S, et al. Metabolic syndrome and ischaemic heart disease in gout. J Clin Rheumatol 2004; 10(3): 105–9

Reyes A. Cardiovascular drugs and serum uric acid. Cardiovasc Drug Ther 2003; 17(5/6): 397–414

Gurwitz J, Kalish S, Bohn R, et al. Thiazide diuretics and the initiation of anti-gout therapy. J Clin Epidemiol 1997; 50(8): 953–9

York M, Hunter D, Chaisson C, et al. Recent thiazide use and the risk of acute gout: the online case-crossover gout study. Arthritis Rheum 2004; 50 (9 Suppl.): S341

Lin H–Y, Rocher L, McQuillan M, et al. Cyclosporine induced hyperuricaemia and gout. N Engl J Med 1989; 321(5): 287–92

Ahn K, Kim Y-G, Lee H, et al. Cyclosporin-induced hyperuricaemia after renal transplant: clinical characteristics and mechanisms. Transplant Proc 1992; 24(4): 1391–2

Noordzij T, Leunisssen K, Van Hooff J. Renal handling of urate and the incidence of gouty arthritis during cyclosporin and diuretic use. Transplantation 1991; 52(1): 64–7

West C, Carpenter B, Hakala T. The incidence of gout in renal transplant recipients. Am J Kidney Dis 1987; 10(5): 369–71

Gores P, Fryd D, Sutherland D, et al. Hyperuricaemia after renal transplantation. Am J Surg 1988; 156: 397–400

Puig J, Michan A, Jimenez M, et al. Female gout clinical spectrum and uric acid metabolism. Arch Intern Med 1991; 141(4): 726–32

Marcen R, Gallego N, Orofino L, et al. Impairment of tubular secretion of urate in renal transplant patients on cyclosporine. Nephron 1995; 70: 307–13

Ifudu O, Tan C, Dulin A, et al. Gouty arthritis in end-stage renal disease: clinical course and rarity of new cases. Am J Kidney Dis 1994; 23(3): 347–51

Fernando O, Sweny P, Varghese Z. Elective conversion of patients from cyclosporin to tacrolimus for hypertrichosis. Transplant Proc 1998; 30: 1243–4

Urbizu J, Zarraga S, Gomez-Ullate P, et al. Safety and efficacy of tacrolimus rescue therapy in 55 kidney transplant recipients treated with cyclosporin. Transplant Proc 2003; 35: 1704–5

Pilmore H, Faire B, Dittmer I. Tacrolimus for the treatment of gout in renal transplantation. Transplantation 2001; 72(10): 1703–5

Van Thiel D, Iqbal M, Jain A, et al. Gastrointestinal and metabolic problems associated with immunosuppression with either CyA or FK 506 in liver transplantation. Transplant Proc 1990; 22 (1 Suppl. 1): 37–40

Najarian J, Fryd D, Strand M, et al. A single institution, randomized, prospective trial of cyclosporin versus azathioprine-antilymphocyte globulin for immunosuppression in renal allograft recipients. Ann Surg 1985; 201(2): 142–57

Tiller D, Hall B, Horvarth J, et al. Gout and hyperuricaemia in patients on cyclosporin and diuretics [letter]. Lancet 1985; I(8246): 453

Kahan B, Flechner S, Lorber M, et al. Complications of cyclosporine-prednisone immunosuppression in 402 renal allograft recipients exclusively followed at a single center from one to five years. Transplantation 1987; 43(2): 197–204

Marcen R, Gallego N, Gamez C, et al. Hyperuricaemia after kidney transplantation in patients treated with cyclosporin. Am J Med 1992; 93: 354–5

Ben Hmida M, Hachicha J, Bahloul Z, et al. Cyclosporin induced hyperuricaemia and gout in renal transplants. Transplant Proc 1995; 27(5): 2722–4

Braun W, Richmond B, Prouva D, et al. The incidence and management of osteoporosis, gout, and avascular necrosis in recipients of renal allografts functioning more than 20 years (level 5A) treated with prednisone and azathioprine. Am J Kidney Dis 1999; 31: 1366–9

Farge D, Liote F, Guillemain R, et al. Hyperuricaemia and gouty arthritis in heart transplant recipients [letter]. Am J Med 1990; 88: 553

Burack D, Griffith B, Thompson M. Hyperuricaemia and gout among heart transplant recipients receiving cyclosporin. Am J Med 1992; 92: 141–6

Wluka A, Ryan P, Miller A, et al. Post-cardiac transplantation gout: incidence and therapeutic complications. J Heart Lung Transplant 2000; 19: 951–6

Robinson L, Switala J, Tarter R, et al. Functional outcome after liver transplantation: a preliminary report. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1990; 71: 426–7

Taillandier J, Alemanni M, Liote F, et al. Serum uric acid and liver transplantation. Transplant Proc 1995; 27(3): 2189–90

Chapman J, Harding N, Griffiths D, et al. Reversibility of cyclosporin nephrotoxicity after three months treatment. Lancet 1985; I: 128–9

Hansen J, Fogh-Anderson N, Leyssac P, et al. Glomerular and tubular function in renal transplant patients treated with and without cyclosporin A. Nephron 1998; 80: 450–7

Cohen S, Boner G, Rosenfeld J, et al. The mechanism of hyperuricaemia in cyclosporin-treated renal transplant recipients. Transplant Proc 1987; 29(1): 1829–30

Zurcher R, Bock H, Thiel G. Hyperuricaemia in cyclosporin treated patients: GFR-related effect. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1996; 11(1): 153–8

Laine L, Holmberg C. Mechanisms of hyperuricaemia in cyclosporin treated renal transplanted children. Nephron 1996; 74: 318–23

Palestine A, Austin H, Nussenblatt R. Renal tubular function in cyclosporine treated patients. Am J Med 1986; 81: 419–24

Deray G, Assogba U, Le Hoang P, et al. Cyclosporin induced hyperuricaemia and gout [letter]. Clin Nephrol 1990; 33(3): 154

Terkeltaub R. Pathogenesis and treatment of crystal-induced inflammation. In: Koopman WJ, editor. Arthritis and allied conditions. Philadelphia (PA): Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2001: 2329–47

Pascual E. Persistence of monosodium urate crystals and lowgrade inflammation in the synovial fluid of patients with untreated gout. Arthritis Rheum 1991; 34(2): 141–5

Pascual E, Batlle-Gualda E, Martinez A, et al. Synovial fluid analysis for diagnosis of intercritical gout. Ann Intern Med 1999; 131: 756–9

Chapman P, Yarwood H, Harrison A, et al. Endothelial activation in monosodium urate monohydrate crystal-induced inflammation. Arthritis Rheum 1997; 40(5): 955–65

Guerne P, Terkeltaub R, Zuraw B, et al. Inflammatory microcrystals stimulate interleukin-6 production and secretion by human monocytes and synoviocytes. Arthritis Rheum 1989; 32(11): 1443–52

Terkeltaub R, Zachariae C, Santoro D, et al. Monocyte-derived neutrophil chemotactic factor/interleukin-8 is a potential mediator of crystal induced inflammation. Arthritis Rheum 1991; 34(7): 894–903

Ryckman C, McColl S, Vandal K, et al. Role of S100A8 and S100A9 in neutrophil recruitment in response to monosodium urate monohydrate crystals in the air-pouch model of acute gouty arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2003; 48(8): 2310–20

Tramontini N, Huber C, Liu-Bryan R, et al. Central role of complement membrane attack complex in monosodium urate crystal-induced neutrophilic rabbit knee synovitis. Arthritis Rheum 2004; 50(8): 2633–9

Terkeltaub R, Curtiss L, Tenner A, et al. Lipoproteins containing apoprotein B are a major regulator of neutrophil responses to monosodium urate crystals. J Clin Invest 1984; 73: 1719–30

Ortiz-Bravo E, Sieck M, Schumacher HR. Changes in the proteins coating monosodium urate crystals during active and subsiding inflammation. Arthritis Rheum 1993; 36(9): 1274–85

Landis RC, Yagnik D, Florey O, et al. Safe disposal of inflammatory monosodium urate monohydrate crystals by differentiated macrophages. Arthritis Rheum 2002; 46(11): 3026–33

Akahoshi T, Namai R, Murakami Y, et al. Rapid induction of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ expression in human monocytes by monosodium urate monohydrate crystals. Arthritis Rheum 2003; 48(1): 231–9

Yagnik D, Evans B, Florey O, et al. Macrophage release of transforming growth factor betal during resolution of monosodium urate monohydrate crystal-induced inflammation. Arthritis Rheum 2004; 50: 2273–80

Palmer D, Highton J, Hessian P. Development of the gout tophus. Am J Clin Pathol 1989; 91(2): 190–5

Taskiran D, Stefanovic-Racic M, Georgescu H, et al. Nitric oxide mediates suppression of cartilage proteoglycan synthesis by interleukin-1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1994; 200(1): 142–8

Murrell G, Jang D, Williams RJ. Nitric oxide activates metalloproteinase enzymes in articular cartilage. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1995; 206(1): 15–21

Cao M, Westerhausen-Larson A, Niyibizi C, et al. Nitric oxide inhibits the synthesis of type-II collagen without altering CoI2A1 mRNA abundance: prolyl hydroxylase as a possible target. Biochem J 1997; 324: 305–10

Clancy RM, Abramson SB. Nitric oxide: a novel mediator of inflammation. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 1995; 210(2): 93–101

Hsieh M–S, Ho H-C, Chou D–T, et al. Expression of matrix metalloproteinase-9 (gelatinase B) in gouty arthritis and stimulation of MMP-9 by urate crystals in macrophages. J Cell Biochem 2003; 89: 791–9

Liu R, Liote F, Rose D, et al. Proline-rich tyrosine kinase 2 and Src kinase signaling transduce monosodium urate crystal-induced nitric oxide production and matrix metalloproteinase 3 expression in chondrocytes. Arthritis Rheum 2004; 50(1): 247–58

Jaramillo M, Naccache P, Olivier M. Monosodium urate crystals synergize with IFN-gamma to generate macrophage nitric oxide: involvement of extra-cellular signal-related kinase 1/2 and NF-kappa B. J Immunol 2004; 172: 5734–42

De Lannoy I, Mandin R, Silverman M. Renal secretion of vinblastin, vincristine and colchicine in vivo. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1994; 268(1): 388–95

Campion E, Glynn R, DeLabry L. Asymptomatic hyperuricaemia: risks and consequence in the normative aging study. Am J Med 1987; 82: 421–6

Mikuls T, MacLean C, Oliveri J, et al. Quality of care indicators for gout management. Arthritis Rheum 2004; 50(3): 937–43

Hande K, Noone R, Stone W. Severe allopurinol toxicity. Description and guidelines for prevention in patients with renal insufficiency. Am J Med 1984; 76: 47–56

Johnson R, Kang D–H, Feig D, et al. Is there a pathogenic role for uric acid in hypertension and cardiovascular renal disease? Hypertension 2003; 41: 1183–90

Baker J, Krishnan E, Chen L, et al. Serum uric acid and cardiovascular disease: recent developments, and where do they leave us? Am J Med 2005; 118: 816–26

Struthers A, Donnan P, Lindasy P, et al. Effect of allopurinol on mortality and hospitalisations in chronic heart failure: a retrospective cohort study. Heart 2002; 87(3): 229–34

Dimeny E. Cardiovascular disease after renal transplantation. Kidney Int 2002; 61 Suppl. 80: S78–84

Fellstrom B. Risk factors for and management of post-transplantation cardiovascular disease. Biodrugs 2001; 15(4): 261–78

Briggs J. Causes of death after renal transplantation. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2001; 16: 1545–9

Valantine H. Caridac allograft vasculopathy after heart transplantation: risk factors and management. J Heart Lung Transplant 2004; 23: S187–93

Mazuelos F, Abril J, Zaragoza C, et al. Cardiovascular morbidity and obesity in adult liver transplant recipients. Transplant Proc 2003; 35(5): 1909–10

Gerhardt U, Grosse H, Hohage H. Influence of hyperglycaemia and hyperuricaemia on long-term transplant survival in kidney transplant recipients. Clin Transplant 1999; 13(5): 375–9

Rosenfeld J. Effect of longterm allopurinol administration on serial GFR in normotensive and hypertensive hyperuricaemic subjects. Adv Exp Med Biol 1974; 41: 581–96

Neal D, Tom B, Gimson A, et al. Hyperuricaemia, gout and renal function after liver transplantation. Transplantation 2001; 72(10): 1689–91

Perez-Ruiz F, Gomez-Ullate P, Amenabar J, et al. Long-term efficacy of hyperuricaemia treatment in renal transplant recipients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2003; 18: 603–6

Vazquez-Mellado J, Hernandez E, Burgos-Vargas R. Primary prevention in rheumatology: the importance of hyperuricaemia. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2004; 18(2): 111–24

Mikuls T, Farrar J, Bilker W, et al. Gout epidemiology: results from the UK general practice research database, 1990–1999. Ann Rheum Dis 2005; 64: 267–72

Klemp P, Stansfield S, Castle B, et al. Gout is on the increase in New Zealand. Ann Rheum Dis 1997; 56: 22–6

Chang H–Y, Pan W-H, Yeh W-T. Hyperuricaemia and gout in Taiwan: results from the nutritional and health survey in Taiwan. J Rheumatol 2001; 28: 1640–6

Buchanan W, Klinenberg J, Seegmiller J. The inflammatory response to injected microcrystalline monosodium urate in normal, hyperuricaemic, gouty and uraemic subjects. Arthritis Rheum 1965; 8: 361–7

Schreiner O, Wandel E, Himmelsbach F, et al. Reduced secretion of proinflammatory cytokines of monosodium urate crystal-stimulated monocytes in chronic renal failure: an explanation for infrequent gout episode in chronic renal failure patients? Nephrol Dial Transplant 2000; 15: 644–9

Lin J, Yu C, Lin-Tan D, et al. Lead chelation therapy and urate excretion in patients with chronic renal diseases and gout. Kidney Int 2001; 60(1): 266–71

Cohen M. Proximal gout following renal transplantation. Arthritis Rheum 1994; 37(11): 1709–10

Cohen M, Cohen E. Enthesopathy and atypical gouty arthritis following renal transplantation: a case controlled study. Rev Rhum Engl Ed 1995; 62(2): 86–90

Gutman A. The past four decades of progress in the knowledge of gout with an assessment of the present state. Arthritis Rheum 1973; 16: 434–45

Becker M, Schumacher HR, Wortmann R, et al. Febuxostat, a novel nonpurine selective inhibitor of xanthine oxidase. Arthritis Rheum 2005; 52(3): 916–23

Baethge B, Work J, Landreneau M, et al. Tophaceous gout in patients with renal transplants treated with cyclosporin A. J Rheumatol 1993; 20(4): 718–20

Peeters P, Sennesael J. Low-back pain caused by spinal tophus: a complication of gout in a kidney transplant recipient. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1998; 13: 3245–7

Thornton F, Torreggiani W, Brennan P. Tophaceous gout of the lumbar spine in a renal transplant patient: a case report and review of the literature. Eur J Radiol 2000; 36(3): 123–5

Riedel A, Nelson M, Joseph-Ridge N, et al. Compliance with allopurinol therapy among managed care enrollees with gout: a retrospective analysis of administrative claims. J Rheumatol 2004; 31(8): 1575–81

Stamp L, Sharpies K, Raill B, et al. The optimal use of allopurinol: an audit or allopurinol use in South Auckland. Aust N Z J Med 2000; 30: 567–72

Murphy B, Schumacher HR. How does patient education affect gout? Clin Rheumatol Pract 1984 Mar/Apr: 77–80

Gibson T, Rodgers A, Simmonds H, et al. Beer drinking and its effect on uric acid. Br J Rheumatol 1984; 23: 203–9

Choi H, Atkinson K, Karlson E, et al. Alcohol intake and risk of gout in men: a prospective study. Lancet 2004; 363: 1277–81

Choi H, Liu S, Curhan G. Intake of purine-rich foods, protein and diary products and relationship to serum levels of uric acid. Arthritis Rheum 2005; 52(1): 283–9

Choi H, Atkinson K, Karlson E, et al. Purine-rich foods, dairy and protein intake and the risk of gout in men. N Engl J Med 2004; 350(11): 1093–103

Fam A. Gout: excess calories, purines, and alcohol intake and beyond: response to a urate-lowering diet. J Rheumatol 2005; 32(5): 773–7

Dessein P, Shipton E, Stanwix A, et al. Beneficial effects of weight loss associated with moderate calorie/carbohydrate restriction, and increased proportional intake of protein and unsaturated fat on serum urate and lipoprotein levels in gout: a pilot study. Ann Rheum Dis 2000; 59: 539–43

Mistry C, Lote C, Gokal R, et al. Effects of sulindac on renal function and prostaglandin synthesis in patients with moderate chronic renal insufficiency. Clin Sci 1986; 70: 501–5

Gambaro G, Perazella M. Adverse renal effects of anti-inflammatory agents: evaluation of selective and nonselective cyclooxygenase inhibitors. J Intern Med 2003; 253(6): 643–52

Stichtenoth D, Frolich J. The second generation of COX-2 inhibitors: what advantages do the newest offer? Drugs 2003; 63(1): 33–45

Schumacher HR, Boicee J, Daikh D, et al. Randomised double blind trial of etoricoxib and indomethacin in treatment of acute gouty arthritis. BMJ 2002; 324: 1488–92

Rubin B, Burton R, Navarra S, et al. Efficacy and safety profile of treatment with etoricoxib 120mg once daily compared with indomethacin 50mg three times daily in acute gout. Arthritis Rheum 2004; 50(2): 598–606

Cheng T, Lai H, Chiu C, et al. A single-blind, randomized, controlled trial to assess the efficacy and tolerability of rofecoxib, diclofenac sodium, and meloxicam in patients with acute gouty arthritis. Clin Ther 2004; 26(3): 399–406

Bresalier R, Snadler R, Quan H, et al. Cardiovascular events associated with rofecoxib in a colorectal adenoma chemoprevention trial. N Engl J Med 2005; 352: 1092–102

Solomon S, McMurray J, Pfeffer M, et al. Cardiovascular risk associated with celecoxib in a clinical trial for colorectal adenoma prevention. N Engl J Med 2005; 352: 1071–80

Cleland L, James M, Stamp L, et al. COX-2 inhibition and thrombotic tendency: a need for surveillance. Med J Aust 2001; 175: 214–7

Crofford L, Oates J, McCune J, et al. Thrombosis in patients with connective tissue diseases treated with specific cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitors: a report of four cases. Arthritis Rheum 2000; 43(8): 1891–6

Bombardier C, Laine L, Reicin A, et al. Comparison of upper gastrointestinal toxicity of rofecoxib and naproxen in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med 2000; 343: 1520–8

Harris K, Jenkins D, Walls J. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs and cyclosporine. Transplantation 1988; 46(4): 598–9

Murray B, Palier M, Ferris T. Effect of cyclosporin administration on renal hemodynamics in conscious rats. Kidney Int 1985; 28: 767–74

Ahern M, McCredie M, Reid C, et al. Does colchicine work? The results of the first controlled study in acute gout. Aust N Z J Med 1987; 17: 301–4

Ben-Chetrit E, Scherrmann J, Zylber-Katz E, et al. Colchicine disposition in patients with Familial Mediterranean Fever with renal impairment. J Rheumatol 1994; 21(4): 710–3

Achten G, Scherrmann J, Christen M. Pharmacokinetics/ bioavailability of colchicine in healthy male volunteers. Eur J Drug Metab Pharmacokinet 1989; 14(4): 317–22

Ben-Chetrit E, Levy M. Colchicine: 1998 update. Semin Arthritis Rheum 1998; 28(1): 48–59

Kuncl R, Duncan G, Watson D, et al. Colchicine myopathy and neuropathy. N Engl J Med 1987; 316(25): 1562–8

Van der Naalt J, Haaxma-Reiche H, Van Den Berg A, et al. Acute neuromyopathy after colchicine treatment. Ann Rheum Dis 1992; 51(11): 1267–8

Wallace S, Singer J, Duncan G, et al. Renal function predicts colchicine toxicity: guidelines for the prophylactic use of colchicine in gout. J Rheumatol 1991; 18(2): 264–9

Cook M, Ramos E, Peterson J, et al. Colchicine neuromyopathy in a renal transplant patient with normal muscle enzyme levels. Clin Nephrol 1994; 42(1): 67–8

Rieger E, Halasz N, Wahlstrom H. Colchicine neuromyopathy after renal transplantation. Transplantation 1990; 49(6): 1196–8

Tapal M. Colchicine myopathy. Scand J Rheumatol 1996; 25: 105–6

Rana S, Giuliani M, Oddis C, et al. Acute onset of colchicine myoneuropathy in cardiac transplant recipients: case studies of three patients. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 1997; 99: 266–70

Grezard O, Lebranchu Y, Birmele B, et al. Cyclosporin induced muscular toxicity [letter]. Lancet 1990; 335(8682): 177

Breil M, Chariot P. Muscle disorders associated with cyclosporin treatment. Muscle Nerve 1999; 22: 1631–6

Simkin P, Gardner G. Colchicine use in cyclosporine treated renal transplant recipients: how little is too much? J Rheumatol 2000; 27(6): 1334–7

Ducloux D, Schuller V, Bresson-Vautrin C, et al. Colchicine myopathy in renal transplant recipients on cyclosporin. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1997; 12: 2389–92

Speeg K, Maldonado A, Liaci J, et al. Effect of cyclosporin on colchicine secretion by a liver canalicular transporter studied in vivo. Hepatology 1992; 15: 899–903

Speeg K, Maldonado A, Liaci J, et al. Effect of cyclosporin on colchicine secretion by the kidney multidrug transporter studied in vivo. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1992; 261(1): 50–5

Menta R, Rossi E, Guariglia A, et al. Reversible acute cyclosporin nephrotoxicity induced by colchicine administration. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1987; 2: 380–1

Braun W. Modification of the treatment of gout in renal transplant recipients. Transplant Proc 2000; 32(1): 199

Groff G, Franck W, Raddatz D. Systemic steroid therapy for acute gout: a clinical trial and review of the literature. Semin Arthritis Rheum 1990; 19(6): 329–36

Vazquez-Mellado J, Cuan A, Magana M, et al. Intradermal tophi in gout: a case controlled study. J Rheumatol 1999; 26(1): 136–40

Gray R, Tenenbaum J, Gottlieb N. Local steroid injection treatment in rheumatic disorders. Semin Arthritis Rheum 1981; 10(4): 231–54

Alloway J, Moriarty M, Hoogland Y, et al. Comparison of triamcinolone acetonide with indomethacin in the treatment of acute gouty arthritis. J Rheumatol 1993; 20(1): 111–3

Ritter J, Kerr L, Valeriano-Marcet J, et al. ACTH revisited: effective treatment for acute crystal induced synovitis in patients with multiple medical problems. J Rheumatol 1994; 21: 696–9

Taylor C, Brooks N, Kelley K. Corticotropin for acute management of gout. Ann Pharmacother 2001; 35(3): 365–8

Axelrod D, Preston S. Comparison of parenteral adrenocorticotropic hormone with oral indomethacin in the treatment of acute gout. Arthritis Rheum 1988; 31(6): 803–5

Getting S, Christian H, Flower R, et al. Activation of melanocortin type 3 receptor as a molecular mechanism for adrenocorticotropic hormone efficacy in gouty arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2002; 46(10): 2765–75

McCarthy G, Barthelemy C, Veum J, et al. Influence of antihyperuricaemic therapy on the clinical and radiographic progression of gout. Arthritis Rheum 1991; 34(12): 1489–94

Li-Yu J, Clayburne G, Sieck M, et al. Treatment of chronic gout: can we determine when urate stores are depleted enough to prevent attacks of gout? J Rheumatol 2001; 28: 577–80

Perez-Ruiz F, Calabozo M, Pijoan J, et al. Effect of uratelowering therapy on the velocity of size reduction of tophi in chronic gout. Arthritis Rheum 2002; 47(4): 356–60

Shoji A, Yamanaka H, Kamatani N. A retrospective study of the relationship between serum urate level and recurrent attacks of gouty arthritis: evidence for reduction of recurrent gouty arthritis with antihyperuricaemic therapy. Arthritis Rheum 2004; 51(3): 321–5

Venkat Raman G, Sharman V, Lee H. Azathioprine and allopurinol: a potentially dangerous combination. J Intern Med 1990; 228: 69–71

Cummins D, Sekar M, Halil O, et al. Myelosuppression associated with azathioprine-allopurinol interaction after heart and lung transplantation. Transplantation 1996; 61(11): 1661–2

Byrne P, Fraser A, Pritchard M. Treatment of gout following cardiac transplantation [letter]. Rheumatology 1996; 35(12): 1329

Sinclair D, Fox I. The pharmacology of hypouricaemic effect of benzbromarone. J Rheumatol 1974; 2: 437–45

Perez-Ruiz F, Alonso-Ruiz A, Calabozo M, et al. Efficacy of allopurinol and benzbromarone for the control of hyperuricaemia: a pathogenic approach to the treatment of primary chronic gout. Ann Rheum Dis 1998; 57: 545–9

Heel R, Brogden R, Speight T, et al. Benzbromarone: a review of its pharmacological properties and therapeutic uses in gout and hyperuricaemia. Drugs 1977; 14(5): 349–66

Zurcher R, Bock H, Thiel G. Excellent uricosuric efficacy of benzbromarone in cyclosporin-A treated renal transplant patients: a prospective study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1994; 9: 548–51

World Health Organization. Benzbromarone, benziodarone: measures following safety review. In: Pharmaceuticals Newsletter No. 2; 2004 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.who.int/medicines/publications/newsletter/en/news2004_2.pdf [Accessed 2005 Sep 1]

Hautekeete M, Henrion J, Naegels S, et al. Severe hepatotoxicity related to benzarone: a report of three cases with two fatalities. Liver 1995; 15: 25–9

Wagayama H, Shiraki K, Sugimoto K, et al. Fatal fulminant hepatic failure associated with benzbromarone [letter]. J Hepatol 2000; 32(5): 874

Arai M, Yokosuka O, Fujiwara K, et al. Fulminant hepatic failure associated with benzbromarone treatment: a case report. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2002; 17(5): 625–6

Van Der Klauw M, Houtmann M, Strieker B, et al. Hepatic injury caused by benzbromarone. J Hepatol 1994; 20(3): 376–9

Masbernard A, Giudicelli C. Ten years experience with benzbromarone in then management of gout and hyperuricaemia. Sth Afr Med J 1981; 59: 701–6

Pui C–H. Urate oxidase in the prophylaxis or treatment of hyperuricaemia. Semin Hematol 2001; 38 (4 Suppl. 10): 13–21

Rozenberg S, Koeger A, Bourgeois P. Urate-oxydase for gouty arthritis in cardiac transplant recipients [letter]. J Rheumatol 1993; 20(12): 2171

Ippoliti G, Negri M, Campana C, et al. Urate oxidase in hyperuricaemic heart transplant recipients treated with azathioprine. Transplantation 1997; 63(9): 1370–1

Pui C–H, Relling M, Lascombes F, et al. Urate oxidase in prevention and treatment of hyperuricaemia associated with lymphoid malignancies. Leukemia 1997; 11(11): 1813–6

Bomalaski J, Holtsberg F, Ensor C, et al. Uricase formulated with polyethylene glycol (Uricase-PEG20): biochemical rationale and preclinical studies. J Rheumatol 2002; 29(9): 1942–9

Sundy J, Ganson N, Kelly S, et al. A phase I study of pegylated uricase (Puricase) in subjects with gout. Arthritis Rheum 2004; 50 (9 Suppl.): S337–8

Ganson N, Kelly S, Scarlett E, et al. Antibodies to polyethylene glycol (PEG) during phase I investigation of PEG-urate oxidase (PEG-uricase, Puricase) for refractory gout [abstract]. Arthritis Rheum 2004; 50 (9 Suppl.): S338

Hoshide S, Takahashi Y, Ishikawa T, et al. PK/PD and safety of a single dose of TMX-67 (febuxostat) in subjects with mild and moderate renal impairment. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids 2004; 23(8–9): 1117–8

Groth C, Backman L, Morales J, et al. Sirolimus (rapamycin)-based therapy in human renal transplantation: similar efficacy and different toxicity compared with cyclosporin. Transplantation 1999; 67(7): 1036–42

Kreis H, Cisterne J, Land W, et al. Sirolimus in association with mycophenylate induction for the prevention of acute graft rejection in renal allograft recipients. Transplantation 2000; 69(7): 1252–60

Morales J, Wramner L, Kreis H, et al. Sirolimus does not exhibit nephrotoxicity compared to cyclosporine in renal transplant recipients. Am J Transplant 2002; 2: 436–42

Jacobs F, Mamzer-Bruneel M, Skhiri H, et al. Safety of mycophenylate mofetil-allopurinol combination in kidney transplant recipients with gout. Transplantation 1997; 64(7): 1087–8

Burnier M, Rutschmann B, Nussberger J, et al. Salt-dependent renal effects of an angiotension II antagonist in healthy subjects. Hypertension 1993; 22: 339–47

Soffer B, Wright J, Pratt J, et al. Effects of losartan on a background of hydrochlorothiazide in patients with hypertension. Hypertension 1995; 26(1): 112–7

Minghelli G, Seydoux C, Goy J, et al. Uricosuric effect of the angiotensin II receptor antagonist losartan in heart transplant recipients. Transplantation 1998; 66(2): 268–71

Del Castillo D, Campistol J, Guirado L, et al. Efficacy and safety of losartan in the treatment of hypertension in renal transplant recipients. Kidney Int 1998; 54 Suppl. 68: S135–S9

Schmidt A, Gruber U, Bohmig G, et al. The effect of ACE inhibitor and angiotension II receptor antagonist therapy on serum uric acid levels and potassium homeostasis in hypertensive renal transplant recipients treated with CsA. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2001; 16: 1034–7

Yamamoto T, Moriwaki Y, Takahashi S, et al. Effect of losartan potassium, an angiotensin II receptor antagonist, on renal excretion of oxypurinol and purine bases. J Rheumatol 2000; 27: 2232–6

Toupance O, Lavaud S, Canivet E, et al. Antihypertensive effect of amlodipine and lack of interference with cyclosporin metabolism in renal transplant recipients. Hypertension 1994; 24(3): 297–300

van der Schaaf M, Hene R, Floor M, et al. Hypertension after renal transplantation calcium channel or converting enzyme blockade? Hypertension 1995; 25(1): 77–81

Chanard J, Toupance O, Lavaud S, et al. Amlodipine reduces cyclosporin-induced hyperuricaemia in hypertensive renal transplant recipients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2003; 18: 2147–53

Sennesael J, Lamote J, Violet I, et al. Divergent effects of calcium channel and angiotensin converting enzyme blockade on glomerulotubular function in cyclosporin-treated renal allograft recipients. Am J Kidney Dis 1996; 27(5): 701–8

Rodicio R. Calcium channel antagonists and renal protection from cyclosporin nephrotoxicity: long term trial in renal transplantation patients. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 2000; 35 (3 Suppl. 1): S7–11

Raman G, Feehally J, Coated R, et al. Renal effects of amlodipine in normotensive renal transplant recipients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1999; 14: 384–8

Milionis H, Kakafika A, Tsouli S, et al. Effects of statin treatment on uric acid homeostasis in patients with primary hyperlipidaemia. Am Heart J 2004; 148: 635–40

Melenovsky V, Malik J, Wichterle D, et al. Comparison of the effects of atorvastatin or fenofibrate on nonlipid biochemical risk factors and the LDL particle size in subjects with combined hyperlipidaemia. Am Heart J 2002; 144(4): e6

Sieb J, Gillessen T. Iatrogenic and toxic mypopathies. Muscle Nerve 2003; 27(2): 142–56

Jardine A, Holdaas H. Fluvastatin in combination with cyclosporin in renal transplant recipients: a review of clinical and safety experience. J Clin Pharm Ther 1999; 24(6): 397–408

Ballantyne C, Corsini A, Davidson M, et al. Risk for myopathy with statin therapy in high-risk patients. Arch Intern Med 2003; 163(5): 553–64

Desager J, Hulhoven R, Harvengt C. Uricosuric effect of fenofibrate in healthy volunteers. J Clin Pharmacol 1980; 20: 560–4

Yamamoto T, Moriwaki Y, Takahashi S, et al. Effect of fenofibrate on plasma concentration and urinary excretion of purine bases and oxypurinol. J Rheumatol 2001; 28: 2294–7

Bastow M, Durrington P, Ishola M. Hypertriglyceridaemia and hyperuricaemia: effects of two fibric acid derivatives (Bezafibrate and fenofibrate) in a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Metabolism 1988; 37(3): 217–20

Hepburn A, Kaye S, Feher M. Fenofibrate: a new treatment for hyperuricaemia and gout? Ann Rheum Dis 2001; 60: 984–6

Feher M, Hepburn A, Hogarth M, et al. Fenofibrate enhances urate reduction in men treated with allopurinol for hyperuricaemia and gout. Rheumatology 2003; 42(2): 321–5

Takahashi S, Moriwaki Y, Yamamoto T, et al. Effects of combination treatment using anti-hyperuricaemic agents with fenofibrate and/or losartan on uric acid metabolism. Ann Rheum Dis 2003; 62: 572–5

Lipscombe J, Lewis G, Cattran D, et al. Deterioration in renal function associated with fibrate therapy. Clin Nephrol 2001; 55(1): 39–44

Tsimihodimos V, Kakafika A, Elisaf M. Fibrate treatment can increase serum creatinine levels [letter]. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2001; 16: 1301

Broeders N, Knoop C, Antoine M, et al. Fibrate-induced increase in blood urea and creatinine: is gemfibrozil the only innocuous agent? Nephrol Dial Transplant 2000; 15: 1993–9

Boissonnat P, Salen P, Guidollet J, et al. The long-term effects of the lipid-lowering agent fenofibrate in hyperlipidaemic heart transplant patients. Transplantation 1994; 58(2): 245–7

Acknowledgements

No sources of funding were used to assist in the preparation of this review. The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Stamp, L., Searle, M., O’Donnell, J. et al. Gout in Solid Organ Transplantation. Drugs 65, 2593–2611 (2005). https://doi.org/10.2165/00003495-200565180-00004

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/00003495-200565180-00004