Summary

Abstract

Esomeprazole, the S-isomer of omeprazole, is the first proton pump inhibitor to be developed as a single optical isomer. It provides better acid control than current racemic proton pump inhibitors and has a favourable pharmacokinetic profile relative to omeprazole.

In large well designed 8-week trials in patients with erosive oesophagitis, esomeprazole recipients achieved significantly higher rates of endoscopically confirmed healed oesophagitis than those receiving omeprazole or lansoprazole. Esomeprazole was effective across all baseline grades of oesophagitis; notably, relative to lansoprazole, as the baseline severity of disease increased, the difference in rates of healed oesophagitis also increased in favour of esomeprazole. In two trials, 94% of patients receiving esomeprazole 40mg once daily achieved healed oesophagitis versus 84 to 87% of omeprazole recipients (20mg once daily). In a study in >5000 patients, respective healed oesophagitis rates with once-daily esomeprazole 40mg or lansoprazole 30mg were 92.6 and 88.8%. Resolution of heartburn was also significantly better with esomeprazole than with these racemic proton pump inhibitors. Long-term (up to 12 months) therapy with esomeprazole effectively maintained healed oesophagitis in these patients.

Esomeprazole 20 or 40mg once daily for 4 weeks proved effective in patients with symptomatic gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) without oesophagitis.

Eradicating Helicobacter pylori infection is considered pivotal to successfully managing duodenal ulcer disease. Ten days’ triple therapy (esomeprazole 40mg once daily, plus twice-daily amoxicillin 1g and clarithromycin 500mg) eradicated H. pylori in 77 to 78% of patients (intention-to-treat) with endoscopically confirmed duodenal ulcer disease.

Esomeprazole is generally well tolerated, both as monotherapy and in combination with antimicrobial agents. The tolerability profile is similar to that of other proton pump inhibitors. Few patients discontinued therapy because of treatment-emergent adverse events (<3% of patients) and very few (<1%) drug-related serious adverse events were reported.

Conclusions: Esomeprazole is an effective and well tolerated treatment for managing GORD and for eradicating H. pylori infection in patients with duodenal ulcer disease. In 8-week double-blind trials, esomeprazole effectively healed oesophagitis and resolved symptoms in patients with endoscopically confirmed erosive oesophagitis. Notably, in large (n >1900 patients) double-blind trials, esomeprazole provided significantly better efficacy than omeprazole or lansoprazole in terms of both healing rates and resolution of symptoms. Long-term therapy with esomeprazole effectively maintained healed oesophagitis in these patients. Esomeprazole was also effective in patients with symptomatic GORD. Thus, esomeprazole has emerged as an effective option for first-line therapy in the management of acid-related disorders.

Pharmacodynami Properties

Esomeprazole inhibits the activity of the H+/K+-ATPase enzyme (the proton pump), and thereby reduces secretion of hydrochloric acid by gastric parietal cells.

Superiority of esomeprazole over omeprazole, lansoprazole, rabeprazole and pantoprazole in terms of elevation of intragastric pH has been shown in a number of randomised, crossover trials (most of which were nonblind) in healthy volunteers and patients with symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD). On the fifth day of treatment intragastric pH was >4 for a mean 59.4 to 69.8% of the monitored 24-hour periods in individuals receiving esomeprazole 40mg daily. These percentages were significantly greater than those with comparators (43.7 to 62% for once-daily esomeprazole 20mg, omeprazole 20 or 40mg, rabeprazole 20mg, pantoprazole 40mg or lansoprazole 30mg daily). Similarly, esomeprazole 20mg daily was superior to omeprazole 20mg or lansoprazole 15mg daily in the maintenance of gastric pH >4. Higher percentages of patients receiving esomeprazole 20 or 40mg than recipients of other agents maintained intragastric pH >4 for periods ranging from at least 8 hours to more than 16 hours. In one nonblind study in 35 patients with GORD receiving esomeprazole 40mg or rabeprazole 20mg daily, pH was >4 for 23.2 and 11%, respectively, of the first 4 hours after administration of the first dose of study medication, indicating a more rapid onset of reduction of intragastric pH with esomeprazole.

Esomeprazole has no apparent effect on a variety of endocrine and metabolic functions but, like other proton pump inhibitors, the drug increases fasting serum gastrin levels in a dose-related fashion.

Pharmacokinetic Profile

Esomeprazole is absorbed rapidly after oral administration, and areas under curves of plasma drug concentration versus time (AUCs) increase in a nonlinear, dose-related fashion after single doses. Systemic exposure to esomeprazole (as shown by mean AUC extrapolated to infinity, AUC∞) increases with repeated administration of the drug (by 90% with 20mg daily and 159% with 40mg daily relative to day 1 after 5 days’ treatment in healthy volunteers). This effect is attributed to reductions in total body clearance and first-pass metabolism with repeated doses. Binding to plasma proteins of esomeprazole (97%) is similar to that seen with omeprazole and other proton pump inhibitors.

Metabolism of esomeprazole is via hepatic cytochrome P 450 (CYP) isoenzymes, chiefly CYP3A4 and CYP2C19, with approximately 80% of each dose being excreted as metabolites in the urine. A small proportion of the population lacks a functional form of the CYP2C19 isoenzyme and are therefore poor metabolisers of esomeprazole. AUC data indicate that dosage adjustments are not necessary in these individuals.

Comparative pharmacokinetic data obtained in patients with GORD show similar times to attainment of peak plasma concentrations with esomeprazole and omeprazole (approximately 1 hour). However, after 5 days’ treatment, the geometric mean AUC∞ for esomeprazole 20mg daily was approximately two times higher than that for omeprazole 20mg daily, whereas that for esomeprazole 40mg daily was over five times higher than omeprazole 20mg (p < 0.0001 for both differences) in a study in 36 evaluable patients. There was also less interpatient variability in AUC∞ values with esomeprazole than with omeprazole, although statistical significance was not stated for this finding.

Systemic exposure to esomeprazole is not increased sufficiently to warrant tolerability concerns in patients with mild to moderate hepatic insufficiency; maximum plasma concentrations (Cmax) increased 28% in 12 patients with mild (Child-Pugh class A) to severe (Child-Pugh class C) hepatic insufficiency. There are no clinically significant gender effects on the drug’s disposition. The potential for interactions between esomeprazole and other drugs is reported to be low and similar to that with omeprazole.

Clinical Efficacy

In patients with erosive oesophagitis: In studies of 8 weeks’ duration (the usual duration for these trials), esomeprazole effectively healed oesophagitis (primary efficacy endpoint) and resolved heartburn (secondary endpoint) in patients with GORD in several large, randomised, double-blind, multicentre trials. Patients received oral esomeprazole 20 or 40mg, lansoprazole 30mg or omeprazole 20mg once daily before breakfast. Patients who showed endoscopically confirmed healed oesophagitis were discontinued from the study at 4 weeks.

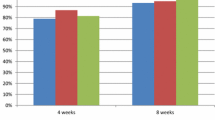

Esomeprazole provided superior efficacy to lansoprazole or omeprazole after 4 to 8 weeks’ treatment, as determined by endoscopically confirmed healed oesophagitis rates. In a large double-blind trial in more than 5000 patients, significantly more recipients of esomeprazole 40mg once daily than lansoprazole 30mg once daily showed healed oesophagitis at 8 weeks (92.6 vs 88.8% of patients; p <0.001). Similarly, ≥90% of esomeprazole recipients (20 or 40mg daily) achieved healed oesophagitis at 8 weeks compared with 84 to 87% of those receiving omeprazole 20mg daily (p < 0.05 all comparisons) in two randomised, double-blind trials. Of these two trials, one evaluated both esomeprazole 20mg and 40mg; a significantly higher percentage of patients achieved healed oesophagitis in both the esomeprazole 20 (89.9% of patients; p < 0.05 vs omeprazole) and 40mg (94.1 %; p < 0.001 vs omeprazole) groups than in the omeprazole 20mg group (86.9%). Evidence-based analysis using pooled data from two trials confirmed that esomeprazole was more effective than omeprazole in healing erosive oesophagitis; 11 patients would need to be treated with esomeprazole 40mg once daily rather than omeprazole 20mg once daily to prevent one treatment failure.

The higher response rates with esomeprazole treatment relative to omeprazole occurred across all baseline grades of disease severity (based on Los Angeles Classification grades). Furthermore, relative to lansoprazole, as the baseline severity of disease increased, the difference in rates of healed oesophagitis also increased in favour of esomeprazole.

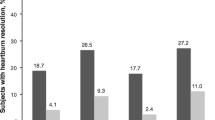

Esomeprazole also proved effective in patients with erosive oesophagitis according to secondary efficacy endpoints (e.g. percentage of heartburn-free days and nights, and the time to sustained resolution of symptoms). Heartburn resolution with esomeprazole was significantly better than that of omeprazole for all secondary efficacy endpoints, with a significantly reduced time to complete resolution of heartburn. Furthermore, esomeprazole recipients experienced significantly fewer nights with heartburn relative to lansoprazole (87.1 vs 85.8% of nights heartburn-free; p ≤ 0.05), with complete resolution of symptoms occurring sooner in the esomeprazole group (7 vs 8 days; p ≤ 0.01); there was no between-group difference in the number of days without heartburn.

Resolution of heartburn matched healed oesophagitis rates in a post-hoc analysis of pooled data from US 8-week randomised, double-blind trials evaluating 4877 patients. After 4 weeks’ treatment with esomeprazole 40mg once daily, 83.4 and 81 % of recipients who had healed oesophagitis were asymptomatic for heartburn and acid regurgitation, respectively, compared with 75.4 and 71.6% of those receiving omeprazole 20mg once daily (p < 0.001 for both comparisons).

Maintenance therapy in patients with GORD: Esomeprazole 20 or 40mg once daily was significantly more effective than placebo in maintaining healed oesophagitis, prolonging the time to recurrence of erosive oesophagitis, in two 6-month randomised, double-blind, multicentre trials. Healed oesophagitis was maintained in 79 and 93% (esomeprazole 20mg), 88 and 94% (esomeprazole 40mg), or 29% (placebo) of patients. Subgroup analyses indicated that maintenance of healing with esomeprazole treatment was not influenced by gender, age (≥65 years vs <65 years of age), initial treatment during the healing phase, time to healing in this phase (4 vs 8 weeks) or baseline severity of erosive oesophagitis. Similar results were reported in a noncomparative trial of 12 months’ duration.

Although there was no statistically significant difference in the percentage of patients who were heartburn-free at 6 months with esomeprazole and placebo treatment, this most likely reflects the fact that only patients with maintained healing remained in the study at 6 months.

A significantly higher percentage of esomeprazole (20mg once daily) than lansoprazole (15mg once daily) recipients remained in remission (primary end-point) at 6 months in a large, randomised, double blind trial (83 vs 74% of patients; p < 0.001). Esomeprazole recipients showed higher rates of remission across all grades of baseline disease severity than lansoprazole-treated patients. Furthermore, significantly more esomeprazole than lansoprazole recipients were asymptomatic at 6 months [heartburn-free (78 vs 71% of patients), acid regurgitation-free (81 vs 72%) and epigastric pain-free (80 vs 75%)].

In patients with symptomatic GORD without oesophagitis: Esomeprazole 20 or 40mg once daily for 4 weeks effectively resolved symptoms in patients with symptomatic GORD without oesophagitis in randomised double-blind trials. Thirty-three to 42% of patients achieved complete resolution of heartburn (no heartburn during the final 7 days of the 4-week studies) with esomeprazole versus 12 to 14% of placebo recipients. Additionally, 63 to 68% of days were heartburn-free with esomeprazole (20 or 40mg once daily) therapy compared with 36 to 46% with placebo. Respective median times to sustained resolution of heartburn were also significantly shorter in patients receiving esomeprazole (12.1 to 17.3 vs 20.8 to 22.3 days).

Eradication of H. pylori infection: Ten days’ triple therapy including esomeprazole 40mg once daily, plus twice daily amoxicillin 1g and clarithromycin 500mg, effectively eradicated H. pylori infection in patients with duodenal ulcer disease. As expected, this esomeprazole-based regimen was significantly (p < 0.001) more effective in eradicating H. pylori infection than 10 days’ dual therapy (esomeprazole plus clarithromycin at the same dosages) [77 vs 52% of patients; intention-to-treat analysis].

Emerging resistance, particularly in the US, to clarithromycin and other antimicrobial agents used in triple therapy regimens is of increasing concern. Of note, pooled data from these two trials plus another small (n = 66) study (dual therapy with the same dosages of esomeprazole plus clarithromycin, or esomeprazole monotherapy) reported in the same publication indicated that 15% of H. pylori clinical isolates collected from patients at baseline were resistant to clarithromycin.

Tolerability

Like other proton pump inhibitors, esomeprazole is safe and well tolerated. In two large 8-week randomised trials (n = 2405 and 1957) and in pooled tolerability data (n = 6682), a similar small proportion of patients (≈1 to 2.6% of patients) receiving esomeprazole 20 or 40mg once daily or omeprazole 20mg once daily discontinued treatment due to an adverse event. There was also no difference in the nature or frequency of individual adverse events; headache, diarrhoea, nausea, abdominal pain and respiratory infection were most commonly reported. No treatment-related serious adverse events were reported with esomeprazole or omeprazole therapy in these studies. There were also no clinically relevant changes in laboratory parameters or vital signs with either treatment.

There were no between-group differences in the tolerability profiles of esomeprazole 40mg once daily or lansoprazole 30mg once daily in a large randomised, double-blind trial in >5000 patients with erosive oesophagitis. Ten percent of patients in each treatment group experienced at least one adverse event considered to be drug-related; the most frequently reported adverse events with either esomeprazole or lansoprazole treatment were headache (5.8 vs 4.5%), diarrhoea (4.2 vs 4.7%), respiratory infection (2.8 vs 3.8%), abdominal pain (2.9 vs 2.9%), flatulence (2.3 vs 2.4%) and nausea (2.1 vs 2.5%). Serious adverse events considered to be treatment related occurred in 0.7 and 0.5% of patients in the esomeprazole and lansoprazole groups, respectively, with 1.8 and 1.9% of recipients discontinuing treatment due to adverse events. There were no clinically relevant changes in laboratory parameters or vital signs in either treatment group.

Triple therapy with esomeprazole plus amoxicillin and clarithromycin for 10 days for the eradication of H. pylori infection was most commonly associated with diarrhoea, taste perversion, and abdominal pain according to pooled tolerability data (number of patients not reported).

Maintenance therapy with esomeprazole 20 or 40mg once daily for 6 months was generally well tolerated in patients with healed GORD in two randomised, double-blind studies in 318 and 375 patients. The nature of drug-related adverse events experienced with maintenance treatment was no different from that experienced with 4 to 8 weeks’ treatment. A 12-month noncomparative study in 807 patients with healed oesophagitis confirmed that esomeprazole 40mg once daily was well tolerated.

Patients who received esomeprazole as maintenance therapy remained in randomised studies for a much longer time than placebo recipients (mean values: 116 to 161 vs 59 and 61.5 days). Therefore, direct comparisons of adverse event incidences were difficult to make. After 1 month of treatment, the incidences of the most common adverse events and the proportions of patients who experienced at least one adverse event were similar in the esomeprazole and placebo treatment groups. Over the 6 months’ duration of these trials, esomeprazole was generally associated with higher rates of discontinuation due to adverse events and higher overall frequencies of adverse events than placebo, possibly because of the longer treatment time with the active drug.

No enterochromaffin-like cell dysplasia, carcinoids or neoplasia were reported in pooled tolerability data from noncomparative and randomised studies in 1326 patients with healed erosive oesophagitis who received esomeprazole 20 or 40mg once daily or placebo for up to 6 or 12 months. Gastric histological scores with both esomeprazole and placebo fluctuated to a minor extent and there were no concerns relating to development of atrophic gastritis or clinically significant changes in enterochromaffin-like cells.

Dosage and Administration

In the US, esomeprazole 20 or 40mg once daily for 4 to 8 weeks is indicated for the healing of erosive oesophagitis associated with GORD; if oesophagitis is not healed, a further 4 to 8 weeks’ therapy may be considered. Esomeprazole 20mg once daily is recommended for the maintenance of healed erosive oesophagitis. Currently, no controlled studies of >6 months duration have been carried out; a noncomparative trial of 12 months’ duration has been conducted. In patients with symptomatic GORD, esomeprazole 20mg once daily for 4 weeks is recommended; if symptoms have not resolved, a further 4 weeks’ treatment may be considered.

For the eradication of H. pylori in patients with duodenal ulcer disease, triple therapy with esomeprazole 40mg once daily plus amoxicillin 1g twice daily and clarithromycin 500mg twice daily for 10 days is recommended.

Esomeprazole capsules should be swallowed whole at least 1 hour before eating; the contents of the capsules (pellets) may be mixed with apple sauce for patients who have difficulty in swallowing. In nursing mothers, a decision should be made whether to discontinue nursing or to discontinue treatment. Although animal studies have shown no evidence of fetal abnormality, there are no well controlled trials in pregnant women (category B rating); thus, the drug should be used during pregnancy only if clearly needed. Dosage adjustments are not necessary in patients who are elderly or in those with renal or mild to moderate hepatic impairment. In patients with severe hepatic impairment, the dosage of esomeprazole should not exceed 20mg daily. The tolerability and effectiveness of esomeprazole have not yet been established in paediatric patients.

Concurrent administration of esomeprazole with warfarin, quinidine or amoxicillin does not produce any clinically significant interactions. Esomeprazole may, however, interfere with the absorption of drugs where gastric pH is an important determinant of bioavailability (e.g. ketoconazole, digoxin and iron salts).

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Thitiphuree S, Talley NJ. Esomeprazole, a new proton pump inhibitor: pharmacological characteristics and clinical efficacy. Int J Clin Pract 2000 Oct; 54(8): 537–41

Langtry HD, Wilde MI. Omeprazole: a review of its use in Helicobacter pylori infection, gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and peptic ulcers induced by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Drugs 1998; 56(3): 447–86

Fitton A, Wiseman L. Pantoprazole: a review of its pharmacological properties and clinical efficacy in the management of acid-related disorders. Drugs 1996; 51(3): 460–82

Langtry HD, Markham A. Rabeprazole: a review of its use in acid-related gastrointestinal disorders. Drugs 1999 Oct; 58: 725–42

Carswell CI, Goa KL. Rabeprazole: an update of its use in acid-related disorders. Drugs 2001; 61(15): 2327–56

Spencer CM, Faulds D. Lansoprazole: a reappraisal of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties, and its therapeutic efficacy in acid-related disorders. Drugs 1994; 48: 404–30

Langtry HD, Wilde MI. Lansoprazole: an update of its pharmacological properties and clinical efficacy in the management of acid-related disorders. Drugs 1997; 54(3): 473–500

Matheson AJ, Jarvis B. Lansoprazole: an update of its place in the management of acid-related disorders. Drugs 2001; 61(12): 1803–35

Spencer CM, Faulds D. Esomeprazole. Drugs 2000 Aug; 60(2): 321–9; discussion 330–1

Huang J-Q, Hunt RH. Pharmacological and pharmacodynamic essentials of H(2)-receptor antagonists and proton pump inhibitors for the practising physician. Baillieres Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2001 Jun; 15(3): 355–70

Zimmermann AE. Esomeprazole: a novel proton pump inhibitor for the treatment of acid-related disorders. Formulary 2000 Nov; 35: 882–93

AstraZeneca LP. Nexium (esomeprazole magnesium): delayed release capsules [prescribing information]. 2001

Hassan-Alin M, Niazi M, Röhss K, et al. Esomeprazole, the S-isomer of omeprazole, is optically stable in humans [abstract no.5697]. Gastroenterology 2000; 118 (4 Suppl.2): A1244–S

Hunt RH. Importance of pH control in the management of GERD. Arch Intern Med 1999 Apr 12; 159: 649–57

Smith JL, Operkun AR, Larkai E, et al. Sensitivity of oesophageal mucosa to pH in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology 1989; 96: 683–9

Bell NJV, Burget D, Howden CW, et al. Appropriate acid suppression for the management of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Digestion 1992; 51 Suppl. 1: 59–67

Wilder-Smith C, Röhss K, Lundin C, et al. Esomeprazole (E) 40 mg provides more effective acid control than pantoprazole (P) 40 mg [abstract no. 352]. Gastroenterology 2000; 118: A22

Röhss K, Lundin C, Rydholm H, et al. Esomeprazole 40 mg provides more effective acid control than omeprazole 40 mg [abstract]. Am J Gastroenterol 2000 Sep; 95: 2432–3

Thomson ABR, Claar-Nilsson C, Hasselgren G, et al. Esomeprazole 40 mg provides more effective acid control than lansoprazole 30 mg during single and repeated administration [abstract]. Gut 2000 Dec; 47 Suppl. III: A63

Wilder-Smith CH, Claar-Nilson C, Hasselgren G, et al. Esomeprazole 40mg provides faster and more effective acid control than rabeprazole 20mg in patients with symptoms of GERD [abstract]. Am J Gastroenterol 2001; 96: S45

Wilder-Smith C, Röhss K, Claar-Nilsson C, et al. Esomeprazole 20 mg provides more effective acid control than lansoprazole 15 mg [abstractno. P49]. Gut 2000 Dec; 47 Suppl. III: A62–3

Wilder-Smith C, Röhss K, Claar-Nilsson C, et al. Esomeprazole 40 mg provides more effective acid control than rabeprazole 20 mg [abstract]. Gut 2000 Dec; 47 Suppl. III: A63

Lind T, Rydberg L, Kylebäck A, et al. Esomeprazole provides improved acid control versus omeprazole in patients with symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2000; 14(7): 861–7

Röhss K, Wilder-Smith CH, Claar-Nilsson C, et al. Esomeprazole 40mg provides faster and more effective control than rabeprazole 20mg in patients with symptoms of GERD [abstract]. Am J Gastroenterol 2001; 96(9): S45

Andersson T, Hassan-Alin M, Hasselgren G, et al. Pharmacokinetic studies with esomeprazole, the (S)-isomer of omeprazole. Clin Pharmacokinet 2001; 40(6): 411–26

Hassan-Alin M, Andersson T, Bredberg E, et al. Pharmacokinetics of esomeprazole after oral and intravenous administration of single and repeated doses to healthy subjects. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2000 Dec; 56(9-10): 665–70

Andersson T, Bredberg E, Sunzel M, et al. Pharmacokinetics (PK) and effect on pentagastrin stimulated peak acid output (POA) of omeprazole (O) and its 2 optical isomers, S-omeprazole/esomeprazole (E) and R-omeprazole (R-O) [abstract no. 5551]. Gastroenterology 2000; 118(4): A1210

De Vault KR, Castell DO. Updated guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Am J Gastroenterol 1999; 94: 1434–42

Äbelö A, Andersson TB, Antonsson M, et al. Stereoselective metabolism of omeprazole by human cytochrome P450 enzymes. Drug Metab Dispos 2000; 28: 966–72

Andersson T, Magner D, Patel J, et al. Esomeprazole 40mg capsules are bioequivalent when administered intact or as the contents mixed with apple sauce. Clin Drug Invest 2001; 21(1): 67–71

Sjovall H, Hagman I, Holmberg J, et al. Pharmacokinetics of esomeprazole in patients with liver cirrhosis [abstract/poster]. Gastroenterology 2000; 118: A21

Hasselgren G, Hassan-Alin M, Andersson T, et al. Pharmacokinetic study of esomeprazole in the elderly. Clin Pharmacokinet 2001; 40(2): 145–50

Naesdal J, Andersson T, Bodemar G, et al. Pharmacokinetics of [14C]omeprazole in patients with impaired renal function. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1986; 40(3): 344–51

Andersson T, Hassan-Alin M, Hasselgren G, et al. Drug interaction studies with esomeprazole, the (S)-isomer of omeprazole. Clin Pharmacokinet 2001; 40(7): 523–37

Richardson P, Hawkey CJ, Stack WA. Proton pump inhibitors: pharmacology and rationale for use in gastrointestinal disorders. Drugs 1998; 56(3): 301–35

Katz PO, Castell DO, Marino V, et al. Comparison of the new PPI esomeprazole, the S-isomer of omeprazole, vs placebo for the treatment of symptomatic GERD [abstract no. 49]. Am J Gastroenterol 2000 Sep; 95: 2424–5

Lauritsen K, Junghard O, Eklund S. Esomeprazole 20mg compared with lansoprazole 15mg for maintenance therapy in patients with healed reflux oesophagitis [abstract no. LB034]. Proceedings of the World Conference of Gastroenterology; 2002 Feb 24-Mar 1; Bangkok, Thailand

Laine L, Fennerty MB, Osato M, et al. Esomeprazole-based Helicobacterpylori eradication therapy and the effect of antibiotic resistance: results of three US multicenter, double-blind trials. Am J Gastroenterol 2000 Dec; 95(12): 3393–8

Castell DO, Kahrilas PJ, Richter JE, et al. Esomeprazole (40mg) compared with lansoprazole (30mg) in the treatment of erosive esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol 2002; 97(3): 575–83

Kahrilas PJ, Falk GW, Johnson DA, et al. Esomeprazole improves healing and symptom resolution as compared with omeprazole in reflux oesophagitis patients: a randomized controlled trial. Esomeprazole Study Investigators. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2000 Oct; 14(10): 1249–58

Richter JE, Kahrilas PJ, Johanson J, et al. Efficacy and safety of esomeprazole compared with omeprazole in GERD patients with erosive esophagitis: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol 2001 Mar; 96(3): 656–65

Johnson DA, Benjamin SB, Vakil NB, et al. Esomeprazole once daily for 6 months is effective therapy for maintaining healed erosive esophagitis and for controlling gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of efficacy and safety. Am J Gastroenterol 2001 Jan; 96(1): 27–34

Vakil NB, Shaker R, Johnson DA, et al. The new proton pump inhibitor esomeprazole is effective as a maintenance therapy in GERD patients with healed erosive oesophagitis: a 6-month, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of efficacy and safety. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2001 Jul; 15(7): 927–35

Maton PN, Vakil NB, Levine JG, et al. Safety and efficacy of long term esomeprazole therapy in patients with healed erosive oesophagitis. Drug Saf 2001; 24(8): 625–35

Wahlqvist P. In Finland, Sweden and the UK, esomeprazole is cost-effective compared with omeprazole for the acute treatment of patients with reflux oesophagitis [abstract/poster]. Value Health 2000; 3: 358

Wahlqvist P. In Finland, Sweden and the UK, on demand treatment with esomeprazole is cost-effective in patients with GORD without oesophagitis [abstract/poster]. Value Health 2000; 3: 360

Wahlqvist P, Higgins A, Green J. Esomeprazole is cost-effective compared with omeprazole for the acute treatment of patients with non-endoscoped GORD in the UK [abstract/poster]. Value Health 2000; 3: 360–1

Wahlqvist P, Junghard O, Higgins A, et al. On-demand treatment is cost-effective in patients with GORD without oesophagitis in the UK [abstract]. Proceedings of the Third Congress of the European Federation of Internal Medicine; 2001 May 9–12; Edinburgh, Scotland

Bate C, Higgins A. On-demand esomeprazole offers value for money compared with “real-life” maintenance omeprazole therapy for patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) without oesophagitis. Proceedings of the Third Congress of the European Federation of Internal Medicine; 2001 May 9–12; Edinburgh, Scotland

Wahlqvist P, Junghard O, Higgins A, et al. Esomeprazole is cost-effective compared with omeprazole in the acute treatment of patients with reflux oesophagitis in the UK [abstract]. Proceedings of the Third Congress of the European Federation of Internal Medicine; 2001 May 9–12; Edinburgh, Scotland

Lundell LR, Dent J, Bennett JR, et al. Endoscopic assessment of oesophagitis: clinical and functional correlates and further validation of Los Angeles classification. Gut 1999; 45: 172–80

Roach AC, Hwang C, Bjorkman DJ. Evidence-based analysis of the benefit of esomeprazole in the treatment of erosive oesophagitis (EE) [abstract]. Gut 2001; 49 Suppl. III: A2755

Vakil NB, Richter JE, Hwang C, et al. Does baseline severity of EE impact healing with esomeprazole? [abstract]. Am J Gastroenterol 2000 Sep; 95: 2439

Howden CW, Ballard II ED, Robieson W. Evidence for therapeutic equivalence of lansoprazole 30mg and esomeprazole 40mg in the treatment of erosive oesophagitis. Clin Drug Invest 2002; 22: 99–109

Johnson DA, Vakil NB, Hwang C, et al. Absence of symptoms in erosive esophagitis patient treated with esomeprazole is a highly reliable indicator of healing [abstract no. 2237]. Gastroenterology 2001; 120 Suppl. 1: A439

Vakil NB, Katz PO, Hwang C, et al. Nocturnal heartburn is rare in patients with erosive esophagitis treated with esomeprazole [abstract no. 2250]. Gastroenterology 2001 Apr; 120 Suppl. 1: A441

Maton PN, Vakil NB, Hwang C, et al. The impact of baseline severity of erosive esophagitis on heartburn resolution in patients treated with esomeprazole or omeprazole [abstract no. 2221]. Gastroenterology 2001 Apr; 120 Suppl. 1: A435–6

Lind T, Junghard O, Lauritsen K. Esomeprazole and lansoprazole in the management of patients with reflux oesophagitis (RO): combining results from two clinical studies. Proceedings of the World Conference of Gastroenterology; 2002 24 Feb-1 Mar; Bangkok, Thailand

Dworkin MS, Gold BD, Swerdlow DL. Helicobacter pylori: review of clinical and public health aspects for the practitioner. Infect Dis Clin Pract 1999; (8): 137–45

Hasselgren B, Claar-Nilsson C, Hasselgren G, et al. Studies in healthy volunteers do not show any electrocardiographic effects with esomeprazole. Clin Drug Invest 2000; 20(6): 425–31

Svoboda AC. Increasing concerns about chronic proton pump inhibitor use. J Clin Gastroenterol 2001; 33(1): 3–10

Maton PN. Omeprazole. Drug Therapy 1991; 324(14): 965–75

Genta RM, Magner DJ, D’Amico D, et al. Safety of long-term treatment with a new PPI, esomeprazole in GERD patients [abstractno. 326]. Gastroenterology 2000; 118 (4 Suppl. 2): A16

Fass R, Fennerty MB, Vakil N. Nonerosive reflux disease: current concepts and dilemmas. Am J Gastroenterol 2001; 96(2): 303–14

Baldi F, Crotta S, Penagini R. Guidelines for the diagnostic and therapeutic management of patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a position statement of the Italian Association of Hospital Gastroenterologists (AIGO), Italian Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (SIED), and Italian Society of Gastroenterology (SIGE). Ital J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1998 Feb; 30: 107–12

Robinson M. New-generation proton pump inhibitors: overcoming the limitations of early-generation agents. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2001 May; 13 Suppl. 1: S43–7

Revicki DA, Wood M, Maton PN, et al. The impact of gastroesophageal reflux disease on health-related quality of life. Am J Med 1998; 104: 252–8

Glise H. Quality of life and cost of therapy in reflux disease. Scand J Gastroenterol 1995; 30 Suppl. 210: 38–42

Welage LS, Berardi RR. Evaluation of omeprazole, lansoprazole, pantoprazole, and rabeprazole in the treatment of acid-related diseases. J Am Pharm Ass 2000; 40(1): 52–62

Galmiche JP, Letessier E, Scarpignato C. Treatment of gastrooesophageal reflux disease in adults. BMJ 1998; 316: 170–3

Berardi RR, Welage LS. Proton pump inhibitors in acid-related diseases. Am J Health-Syst Pharm 1998; 55(1): 2289–98

Horn J. The proton pump inhibitors: similarities and differences. Clin Ther 2000; 22(3): 266–80

DiPalma JA. Management of severe gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Clin Gastroenterol 2001; 32(1): 19–26

Edwards SJ, Lind T, Lundell L. Systematic review of proton pump inhibitors for the acute treatment of reflux oesophagitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2001; 15(11): 1729–36

Mujica VR, Rao SSC. Recognising atypical manifestations of GERD: asthma, chest pain, and otolaryngologic disorders may be due to reflux. Postgrad Med 1999 Jan; 105: 53–66

Colin-Jones DG. The role and limitations of H2-receptor antagonists in the treatment of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1995; 9 (Suppl. 1): 9–14

Eisen G. The epidemiology of gastroesophageal reflux disease: what we know and what we need to know. Am J Gastroenterol 2001; 96 Suppl.: S16–8

Bloom BS, Glise H. What do we know about gastroesophageal reflux disease? Am J Gastroenterol 2001; 96 Suppl.: S1–5

Richter JE. Long-term management of gastroesophageal reflux disease and its complications. Am J Gastroenterol 1997; 92(4): S30–5

Kahrilas PJ. Gastroesophageal reflux disease. JAMA 1996; 276(12): 983–8

Lind T, Havelund T, Carlsson R, et al. Heartburn without oesophagitis: efficacy of omeprazole therapy and features determining therapeutic response. Scand J Gastroenterol 1997; 32: 974–9

Carlsson R, Dent J, Watts R, et al. Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in primary care: an international study of different treatment strategies with omeprazole. Euro J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1997; 10: 119–24

Smout AJPM. Endoscopy-negative acid reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1997; 11 Suppl.: 81–5

Galmiche J-P, Barthelemy P, Hamelin B. Treating the symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a double-blind comparison of omeprazole and cisapride. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1997; 11: 765–73

Kahrilas PJ. Strategies for medical management of reflux disease. Baillieres Clin Gastroenterol 2000 Oct; 15: 775–91

Dent J, Jones R, Kahrilas P, et al. Management of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in general practice. BMJ 2001 Feb 10; 322: 344–7

Stewart AL, Greenfield S, Hays RD, et al. Functional status and well-being of patients with chronic conditions: results from the Medical Outcomes Study. JAMA 1989; 262: 907–13

Henke CJ, Levin TR, Henning JM, et al. Work loss costs due to peptic ulcer disease and gastroesophageal reflux disease in health maintenance organization. Am J Gastroenterol 2000; 95: 788–92

Wahlqvist P. Symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease, perceived productivity, and health-related quality of life. Am J Gastroenterol 2001; 96 Suppl.: S57–61

Dent J, Fendrick AM, Fennerty MB, et al. An evidence-based appraisal of reflux disease management: the Genval Workshop Report. Gut 1999; 44 Suppl. 2: S1–16

Dimenas E, Glise H, Hallerback B, et al. Quality of life in patients with upper gastrointestinal symptoms. An improved evaluation of treatment regimens? Scan J Gastroenterol 1993; 28(8): 681–7

Hassall E. Peptic ulcer disease and current approaches to Helicobacter pylori. J Pediatr 2001; 138: 462–8

Brown LF, Wilson DE. Gastroduodenal ulcers: causes, diagnosis, prevention and treatment. Comp Ther 1999; 25(1): 30–8

Vakil NB, Go ME Debating the role of Helicobacter pylori infection. Am J Manag Care 2001; 7 Suppl. 1: S27–32

Lee J, O’Morain C. Who should be treated for Helicobacter pylori infection? A review of cnsensus conferences and guidelines. Gastroenterology 1997 Dec; 113 Suppl.: S99–106

Howden CW, Hunt RH. Guidelines for the management of Helicobacter pylori infection. Am J Gastroenterol 1998 Dec; 93: 2330–8

Go FM, Vakil N. Treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection: gastrointestinal infections. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 1999; 15(1): 72

Hoffman JS, Cave CR. Treatment of Helicobacter pylori. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 2001; 17(1): 30–4

Hoffman JS. Pharmacological therapy of Helicobacter pylori infection. Sem Gastroenterol Dis 1997; 8(3): 156–63

Anon. Esomeprazole (Nexium). Med Lett Drugs Ther 2001 Apr 30; 43 (1103): 36-7

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Various sections of the manuscript reviewed by: F. Baldi, Servizio di Gastroenterologia, Ospedale Policlinico Santa Orsola, Bologna, Italy; M. Byrne, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina, USA; D.O. Castell, Department of Medicine, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, South Carolina, USA; J.W. Freston, Department of Medicine, University of Connecticut Health Center, Farmington, Connecticut, USA; J.G. Hatlebakk, Department of Medicine, Haukeland Sykehus University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway; P. Katelaris, Gastroenterology Unit, Concord Repatriation General Hospital, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia; R.J.F. Laheij, Department of Gastroenterology, UMC St Raboud, Nijmegen, The Netherlands; M. Robinson, University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma Foundation for Digestive Research, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, USA.

Data Selection

Data Selection Sources: Medical literature published in any language since 1980 on esomeprazole, identified using Medline and EMBASE, supplemented by AdisBase (a proprietary database of Adis International). Additional references were identified from the reference lists of published articles. Bibliographical information, including contributory unpublished data, was also requested from the company developing the drug.

Search strategy: Medline search terms were ‘esomeprazole’ or ‘perprazole’ or ‘s-omeprazole. EMBASE search terms were ‘esomeprazole’ or ‘perprazole’. AdisBase search terms were ‘esomeprazole’ or ‘perprazole’ or ‘s-omeprazole’. Searches were last updated 4 April 2002.

Selection: Studies in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease or Helicobacter pylori infection who received esomeprazole. Inclusion of studies was based mainly on the methods section of the trials. When available, large, well controlled trials with appropriate statistical methodology were preferred. Relevant pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic data are also included.

Index terms: esomeprazole, proton pump inhibitor, peptic ulcer disease, duodenal ulcer, gastric ulcer, Helicobacter pylori, gastro-oesophageal reflux disease, acid-related dyspepsia, pharmacodynamics, pharmacokinetics, therapeutic use.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Scott, L.J., Dunn, C.J., Mallarkey, G. et al. Esomeprazole. Drugs 62, 1091–1118 (2002). https://doi.org/10.2165/00003495-200262070-00006

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/00003495-200262070-00006