Abstract

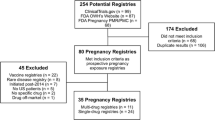

Scientifically valid data on the safety of drug use during pregnancy are a significant public health need. Data are rarely available on the fetal effects of in utero exposure in human pregnancies, particularly when a drug is first marketed. Data from animal reproductive toxicology studies, which function as a screen for potential human teratogenicity, are usually all that is available in a product’s labelling. For practising clinicians, translating known animal risks into an accurate assessment of teratogenic risks in their patients is very difficult, if not impossible. Without human data on the effects of in utero drug exposure, it is difficult for physicians and other healthcare providers (e.g. genetic counsellors) to adequately counsel patients about fetal risks. Therefore, a pregnant woman may decide to unnecessarily terminate a wanted pregnancy or forego needed drug therapy. In spite of the lack of data on the safety of drug use during human pregnancies, pregnant women are exposed to drugs either as prescribed therapy or inadvertently before pregnancy is known (over one-half of pregnancies are unplanned). Because little is known about the teratogenic potential of a drug in humans before marketing, post-marketing surveillance of drug use in pregnancy is critical to the detection of drug-induced fetal effects. The existing passive mechanism of spontaneous reporting of adverse drug effects is inadequate to routinely detect drug-induced fetal risks or lack of such risks. Therefore, post-marketing pregnancy exposure registries are being increasingly used to proactively monitor for major fetal effects and to describe margins of safety associated with drug exposure during pregnancy. However, differing methodological rigour has been applied to the development of pregnancy exposure registries. It is important that all pregnancy registries develop epidemiologically sound written study protocols a priori. It is only through the use of rigourous methodology and procedures that data from pregnancy exposure registries will withstand scientific scrutiny. Successful recruitment of an adequate number of exposed pregnancies, aggressive follow-up, and complete and accurate ascertainment of pregnancy outcome are critical attributes of a well-designed registry.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration. Guideline for the study and evaluation of gender differences in the clinical evaluation of drugs. Fed Regist 1993; 58 (139): 39406–16

Mastroianni AC, Faden R, Federman D, editors. Risks to reproduction and offspring. In: Women and health research: ethical and legal issues of including women in clinical trials. Washington, DC: Natl Acad Sci Press, 1994: 175–202

Mitchell AA. Special considerations in studies of drug-induced birth defects. In: Strom BL, editor. Pharmacoepidemiology. 3rd ed. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons Ltd, 2000: 749–63

Ward RM. Difficulties in the study of adverse fetal and neonatal effects of drug therapy during pregnancy. Semin Perinatol 2001; 25(3): 191–5

Rogers JM, Kavlock RJ. Developmental toxicity. In: Klaassen CD, editor. Casarett & Doull’s Toxicology: the basic science of poisons. 6th ed. New York; McGraw-Hill, 2001: 351–85

Schardein JL. Chemically induced birth defects. 3rd ed. New York: Marcel Dekker Inc., 2000

Kaufman DW, Kelly JP, Rosenberg L, et al. Recent patterns of medication use in the ambulatory adult population of the United States. JAMA 2002 Jan 16; 287(3): 337–44

Colley GB, Brantley MD, Larson MK. 1997 family planning practices and pregnancy intention. Atlanta (GA): Division of Reproductive Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2000

Ventura SJ, Mosher WD, Curtin SC, et al. Trends in pregnancies and pregnancy rates by outcome, United States, 1976-96. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat 2000; 21(56): 1–47

De Vigan C, De Walle HEK, Cordier S, et al. Therapeutic drug use during pregnancy: a comparison in four European countries. J Clin Epidemiol 1999; 52(10): 977–82

Lacroix I, Damase-Michel C, Lapeyre-Mestre M, et al. Prescription of drugs during pregnancy in France. Lancet 2000; 356: 1735–6

Mitchell AA, Hernandez-Diaz S, Louik C, et al. Medication use in pregnancy; 1976-2000 [abstract]. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2001; 10Suppl. 1: S146

Kennedy D, Goldman S, Lillie R. Spontaneous reporting in the United States. In: Strom B, editor. Pharmacoepidemiology. 3rd ed. Chichester; John Wiley & Sons Ltd, 2000: 151–74

US Food and Drug Administration. Office of Women’s Health. List of pregnancy registries [online]. Available from URL: http://www.fda.gov/womens/registries/default.htm

US Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for industry: establishing pregnancy exposure registries. August 2002 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.fda.gov/cder/guidance/3626fnl.pdf [Accessed 2003 Jan 2]

21 Code of Federal Regulations (CFR). 201.57(f)(6) [online]. Available from URL: http://www.access.gpo.gov/nara [Accessed 2003 Jan 2]

International Society for Pharmacoepidemiology. Guidelines for good epidemiology practices for drug, device, and vaccine research in the United States. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 1996; 5: 333–8

Strom BL, editor. Pharmacoepidemiology. 3rd ed. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons Ltd, 2000

Hartzema AG, Porta M, Tilson HH, editors. Pharmacoepidemiology: an introduction. 3rd ed. Cincinnati (OH): Harvey Whitney Books, 1998

Honein MA, Paulozzi LJ, Cragan JD, et al. Evaluation of selected characteristics of pregnancy drug registries. Teratology 1999; 60: 356–64

Strom BL. Sample size considerations for pharmacoepidemiology studies. In: Strom BL, editor. Pharmacoepidemiology. 3rd ed. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons Ltd, 2000: 31–9

Gail M. Computations for designing comparative poisson trials. Biometrics 1974; 30: 231–7

Sumatriptan/naratriptan and lamotrigine pregnancy registries interim reports. PharmaResearch Corporation, Wilmington (NC), USA 28403. 800–336–2176

Reiff-Eldridge R, Heffner CR, Ephross SA, et al. Monitoring pregnancy outcomes after prenatal drug exposure through prospective pregnancy exposure registries: a pharmaceutical company commitment. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2000; 182: 159–63

The North American Pregnancy and Epilepsy Registry. A North American registry for epilepsy and pregnancy, a unique public/private partnership of health surveillance. Epilepsia 1998; 39 (7): 793–8

Chambers CD, Braddock SR, Briggs GG, et al. Postmarketing surveillance for human teratogenicity: a model approach. Teratology 2001; 64(5): 252–61

Shields KE, Gahil K, Seward J, et al. Varicella vaccine exposure during pregnancy: data from the first five years of the pregnancy registry. Obstet Gynecol 2001; 98: 14–9

Holmes LB. Editorial: need for inclusion and exclusion criteria for the structural abnormalities recorded in children born from exposed pregnancies. Teratology 1999; 59: 1–2

Ellish NJ, Saboda K, O’Connor J, et al. A prospective study of early pregnancy loss. Hum Reprod 1996; 11: 406–12

US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Metropolitan Atlanta congenital defects program procedure manual and guide to computerized anomaly record. Atlanta (GA): 1998: A32–A100

March of Dimes Birth Defect Foundation. Quick reference: birth defects and genetics [online]. Available from URL: http://www.modimes.org [Accessed 2003 Jan 2]

Leippig KA, Werler MM, Can CI, et al. Predictive value of minor anomalies: I. Association with major malformations. J Pediatr 1987; 110: 530–7

Khoury MJ, Moore CA, James LM, et al. The interaction between dysmorphology and epidemiology: methodologic issues of lumping and splitting. Teratology 1992; 45(2): 133–8

Scheurle A, Tilson H. Birth defect classification by organ system: a novel approach to heighten teratogenic signaling in a pregnancy registry. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2002; 11: 1–11

National Birth Defects Prevention Network [online]. Available from URL: http://www.nbdpn.org [Accessed 2003 Jan 2]

Edmonds LD, Layde PM, James LM, et al. Congenital malformations surveillance: two American systems. Int J Epidemiol 1981; 10: 247–52

CDC National Center for Health Statistics [online]. Available from URL: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs [Accessed 2003 Jan 2]

International Clearinghouse for Birth Defects Monitoring Systems [online]. Available from URL: http://www.icbd.org [Accessed 2003 Jan 2]

Goldstein DJ, Sundell KL, DeBrota DJ, et al. Determination of pregnancy outcome risk rates after exposure to an intervention. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2001; 69: 7–13

International Society for Pharmacoepidemiology. Data privacy, medical record confidentiality, and research in the interest of public health. 1977 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.pharmacoepi.org/resources/privacy.htm [Accessed 2003 Jan 2]

US Federal Regulations on the Protection of Human Subjects. 45 Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) parts 46 & 164 and 21 CFR parts 50 & 56 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.access.gpo.gov/nara [Accessed 2003 Jan 2]

US Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. 45 Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) 164.512 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.access.gpo.gov/nara

Standards for privacy of individually identifiable health information [online]. Available from URL: http://www.hhs.gov/ocr/hipaa/guidelines/guidanceallsections.pdf [Accessed 2003 Dec 12].

White A, Eldridge R, Andrews E. Birth outcomes following zidovudine exposure in pregnant women: the antiretroviral pregnancy exposure registry. Acta Paediatr Suppl 1997; 421: 86–8

Lipkowitz MA. The American College of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology Registry for allergic, asthmatic pregnant patients (RAAPP). J Allergy Clin Immunol 1999; 103: S364–72

Scialli AR. The Organization of Teratology Information Services (OTIS) registry study. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1999; 103: S373–6

Mitchell AA. Systematic identification of drugs that cause birth defects: a new opportunity. N Engl J Med 2003 Dec 25; 349(26): 2556–9

US Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for industry. Postmarketing adverse experience reporting for human drug and licensed biological products: clarification of what to report, August 1997 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.fda.gov/cder/guidance/1830fnl.pdf [Accessed 2003 Jan 2]

21 CFR 310.305(c)(1), 314.80(c)(2)(iii) and (e), and 600.80(c)(1), (c)(2)(iii) and (e) [online]. Available from URL: http://www.access.gpo.gov/nara [Accessed 2003 Jan 2]

21 CFR 314.80(a) and 600.80(a) [online]. Available from URL: http://www.access.gpo.gov/nara [Accessed 2003 Jan 2]

21 CFR 314.81(b)(2)(vii), 314.98(c), 601.70, and 601.28 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.access.gpo.gov/nara [Accessed 2003 Jan 2]

US Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for industry: E2C clinical safety data management: periodic safety update reports for marketed drugs. November 1996 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.fda.gov/cder/guidance/1351fnl.pdf [Accessed 2003 Jan 2]

Kweder SL, Kennedy DL, Rodriguez E. Turning the wheels of change: FDA and pregnancy labeling. The International Society for Pharmacoepidemiology, Scribe Newsletter 2000; 3(4): 2–4, 10

Acknowledgments

The authors have received no sources of funding that were used to assist in producing this article. The authors have no potential conflicts of interest that may be directly relevant to the contents of this manuscript. This article is based on the August 2002 US FDA Guidance for Industry: Establishing Pregnancy Exposure Registries, which represents the FDA’s thinking on this topic at that time. For the full text of the guidance see {rshttp://www.fda.gov/cder/guidance/3626fnl.pdf. Any deviations from that guidance contained in this article are minor and included for clarification and should not be construed as representing changes in the policies or position of the US FDA.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kennedy, D.L., Uhl, K. & Kweder, S.L. Pregnancy Exposure Registries. Drug-Safety 27, 215–228 (2004). https://doi.org/10.2165/00002018-200427040-00001

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/00002018-200427040-00001