Abstract

Severe burn injury causes hepatic dysfunction that results in major metabolic derangements including insulin resistance and hyperglycemia and is associated with hepatic endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress. We have recently shown that insulin reduces ER stress and improves liver function and morphology; however, it is not clear whether these changes are directly insulin mediated or are due to glucose alterations. Metformin is an antidiabetic agent that decreases hyperglycemia by different pathways than insulin; therefore, we asked whether metformin affects postburn ER stress and hepatic metabolism. The aim of the present study is to determine the effects of metformin on postburn hepatic ER stress and metabolic markers. Male rats were randomized to sham, burn injury and burn injury plus metformin and were sacrificed at various time points. Outcomes measured were hepatic damage, function, metabolism and ER stress. Burn-induced decrease in albumin mRNA and increase in alanine transaminase (p < 0.01 versus sham) were not normalized by metformin treatment. In addition, ER stress markers were similarly increased in burn injury with or without metformin compared with sham (p < 0.05). We also found that gluconeogenesis and fatty acid metabolism gene expressions were upregulated with or without metformin compared with sham (p < 0.05). Our results indicate that, whereas thermal injury results in hepatic ER stress, metformin does not ameliorate postburn stress responses by correcting hepatic ER stress.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Liver dysfunction and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress are two major consequences of burn injury (1,2). It is well established that burn injury induces hepatic acute-phase response and decreases albumin production and that these conditions persist over a prolonged period of time (1–5). In addition, burn injury upregulates hepatic ER stress (6,7), causing hepatic damage that can be detrimental to recovery. We previously published rodent studies that showed that insulin treatment after burn attenuates these processes and enhances hepatic function (6). We expect that insulin treatment may improve postburn morbidity and mortality in patients; however, the mechanism of action of insulin in the context of burn injury is unclear.

To determine whether the beneficial effects of insulin treatment are due to insulin-specific signaling or glucose modulation, we attenuated hyperglycemia with metformin, an antidiabetic drug. Recently, it was reported that metformin reduces burn-induced hyperglycemia and insulin resistance, indicating an improvement in postburn patient outcome (8). A similar effect was also observed in metformin-treated burn rats (9). Metformin activates multiple physiological pathways, including energy sensor AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) (10,11). The activation of AMPK leads to the inhibition of hepatic gluconeogenesis (12). Whereas many studies claim the capacity of metformin to suppress hepatic gluconeogenesis (10,13–15), some report that metformin primarily decreases plasma glucose by activating glucose utilization (16). In addition, metformin is known to mobilize fat in the liver (17). However, it is important to this study that metformin decreases blood glucose levels by non-insulin-mediated mechanisms, which allows us to distinguish between insulin- and glucose-mediated effects.

The aim of the present study was to determine whether postburn metforminmediated glucose modulation reduces hepatic ER stress, alters hepatic metabolic marker expressions and improves function. We hypothesized that metformin does not alleviate postburn ER stress and that the beneficial effects of insulin are due to insulin-specific effects.

Materials and Methods

Animals and Treatments

All procedures were in accordance with current National Institutes of Health guidelines and were approved by the University of Texas Medical Branch Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. All animals were housed in wire-bottom cages with a 12-h light-dark cycle and received food and water ad libitum for the entire study period.

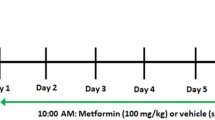

A well-established method (18) was used to induce a 60% total body surface area scald burn in adult male Sprague Dawley rats (approximately 350 g). Rats received analgesia (buprenorphine, 0.05 mg/kg; intramuscularly) and were anesthetized with ketamine (40 mg/kg body weight; intraperitoneally) and xylazine (5 mg/kg body weight; intraperitoneally) before burn. These animals were secured in a protective mold with an opening of approximately 60% of total body surface area. The exposed skin was immersed in 96–100°C water (10 s back, 1.5 s front) to induce third-degree burn. After receiving thermal injury, rats were resuscitated with Ringer lactate (60 mL/kg; intraperitoneally). Analgesia was administered every 12 h. Sham animals received the same treatment except for the scald burn. Metformin (450 mg/kg per os [PO]; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was administered immediately after burn. Animals were sacrificed at 24-or 48-h postburn, and livers were rapidly removed and frozen in liquid nitrogen.

Western Blotting

Livers were homogenized in lysis buffer (150 mmol/L NaCl, 50 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 7.8, 1% [w/v] Triton X-100, 1 mmol/L EDTA, 0.5 mmol/L phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride) with a protease inhibitor (Roche Molecular Bio-chemicals, Indianapolis, IN, USA) and phosphatase inhibitor (Sigma-Aldrich). Samples were centrifuged, and protein concentrations were measured by BCA assay (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). A total of 25 µg denatured protein from tissues were separated on sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) gel. After transfer to nitrocellulose membrane, the membrane was blocked with 5% nonfat milk solution and washed with buffer (Trisbuffered saline, 0.05% Tween). Primary antibodies for p-AMPK and β-actin, and anti-rabbit IgG was purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA) and used at the recommended dilutions. The bound antibody was detected by SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (Thermo Scientific).

RNA Isolation and Gene Expression Analysis

Total RNA was extracted from the livers by using an RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) and was reverse-transcribed by using a High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems; Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed on the ABI PRISM 7000 Sequence Detection System with SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems; Life Technologies). The 18S rRNA was used as the housekeeping gene to normalize expression. PCR primer sequences are available upon request.

Liver Injury Measurement

Alanine transaminase (ALT) activity levels were determined in rat livers using enzymatic kits (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI, USA). Activity was normalized to protein concentration measured by BCA Assay (Thermo Scientific).

Liver Triglyceride Content

Liver lipids were extracted based on the method described by Folch et al. (19). Briefly, liver homogenates were mixed with a chloroform-methanol (2:1) mixture. After centrifugation, the bottom organic layer was removed and evaporated under a stream of nitrogen. Triglyceride concentration was measured enzymatically (INFINITY; Thermo Scientific).

Statistical Analysis

All data are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean. Statistical significance was examined with one-way analysis of variance with a Tukey post hoc test, unless noted otherwise. All data were analyzed by using GraphPad Prism software.

Results

Hepatic AMPK Activation

To determine AMPK activation, a downstream target of metformin, we measured phosphorylated-AMPK (p-AMPK) levels in the livers by Western blot. As expected, there was a significant increase (p < 0.05) in the phosphorylation of AMPK (at Ser108) in metformin-treated livers compared with nontreated livers (Figure 1). This result confirmed the adequate administration of the drug, since phosphorylation at this site is a requirement for the activation of the AMPK enzyme (20).

Hepatic Function

We investigated the effects of metformin on albumin expression and ALT levels. At 24-h postburn, there was a nonsignificant decrease in albumin expression in burn livers; however, there was a further decrease with metformin treatment (Figure 2A). At 48-h postburn, there were no significant differences between the groups.

In addition, we measured ALT enzyme activity. At 24-h postburn, there was a significant increase in ALT levels in both burn groups (Figure 2B; p < 0.01 for both burn versus sham, and burn + metformin versus sham.) These results indicate that burn-induced liver dysfunction but metformin did not correct it.

Hepatic ER Stress

As expected, ER stress markers were significantly increased in burn injury (Figure 3). We measured x-box protein 1 (Xbp-1) spliced, DnaJ homolog subfamily B member 9 (Dnajb9), protein disulfide isomerase family A member 3 (Pdia3), and CCAAT/enhancer binding protein (Chop) mRNA levels and found that all of these ER stress-related gene expressions were significantly upregulated (p < 0.05 versus sham) at 24-h postburn. Metformin did not have any effects on ER stress at this time point. At 48-h postburn, ER stress was induced in burn but less so than at 24-h postburn. Metformin further upregulated expression (p < 0.05 versus sham). Our results confirm that ER stress is increased in burn; however, metformin did not reduce ER stress either at 24- or 48-h postburn.

Metformin augments hepatic ER stress after burn. ER stress markers were assessed at the mRNA level. Chop is a downstream target of PERK, whereas Bip, Dnajb9 and Pdia3 are activated by the spliced form of Xbp-1. Both 24-h (A) and 48-h (B) postburn time points are shown. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 versus sham.

Hepatic Gluconeogenesis

To examine the effects of metformin on hepatic gluconeogenesis, we measured peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator 1-α (Pgc1), glucose 6-phosphatase (G6pc) and phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase 1 (Pck1) gene expressions (Figure 4). Although burn induces hepatic gluconeogenesis, only at 24-h postburn were the expressions increased in burn compared with sham (p < 0.05). Moreover, metformin did not reduce these expressions.

At 48-h postburn, there were similar expression levels of G6pc and Pck1 among the treatment groups. Pgc1 was increased ∼40-fold with metformin treatment (p < 0.001 versus all other groups and time points). These results show that there is a time-dependent modification in gluconeogenic gene expression and that, with the exception of Pgc1 expression at 48-h postburn, metformin does not alter gluconeogenic gene expression in burn livers.

Hepatic Fatty Acid and Glucose Metabolism

Because metformin is known to mobilize energy within the liver, we assessed the expression levels of acyl-CoA oxidase (Acoxl), fatty acid translocase (Cd36), fatty acid synthase (Fasn), stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1 (Scd1), glucose transporter 1 (Glut1) and glucose transporter 4 (Glut4). Many of these gene expressions had a trend to increase in burned animals compared with sham at both time points and were significantly increased in burn + metformin compared to sham (Figure 5). In addition, at 48-h postburn, expressions were significantly upregulated in Acox1 (100-fold), Cd36 (50-fold), Scd1 (15-fold), Glut1 (250-fold) and Glut4 (20-fold) (p < 0.01 versus all other groups and time points). Our results signify a vast energy mobilization after burn, especially with metformin treatment.

Hepatic Triglyceride Content

Because nutrient metabolism gene expressions were altered in the burn livers, we measured triglyceride content to determine whether there was a physiological effect (Figure 6). We found that triglyceride content was slightly increased in burn livers and had a trend to normalize with metformin treatment. These data suggest that metformin potentially reduces burn-induced hepatic steatosis by increasing fatty acid metabolism.

Discussion

The aim of the current study was to determine the effects of metformin on burn-induced ER stress and hepatic metabolic markers. We found that while metformin did not reduce burn-induced liver injury and ER stress, it increased energy metabolism, thereby potentially normalizing burn-induced hepatic steatosis. These results indicate that the beneficial effects observed with insulin administration are most likely associated with insulin-specific modulations and not via glucose alterations. Metformin has been used as an antidiabetic drug for nearly a century. Previously, others have shown that metformin reduces burn-induced hyperglycemia by increasing glucose tolerance (8). In addition to patient data, there are rat data that also indicate that metformin decreases blood glucose levels in burn-injured rats (9). Recently, we demonstrated that, with insulin treatment, burn-induced hyperglycemia as well as liver damage is corrected, suggesting an association between glucose levels and hepatic ER stress (6,21). However, it was not clear whether the improved outcomes were due to insulin action directly or due to reduced glucose levels.

Although metformin reduces blood glucose, it is unknown what its effects are on burn livers. We hypothesized that metformin does not alleviate postburn ER stress and that the beneficial effects of insulin previously published were due to insulin-specific effects. In concurrence with previous data, burn caused ER stress and liver dysfunction; these conditions, however, were not normalized with metformin treatment. Albumin levels were decreased and ALT levels were increased similarly in burn rats with or without metformin. Elevated ALT is a marker for liver damage. Although metformin is known to decrease elevated ALT levels back to baseline in diabetic patients, this does not seem to be the case after burn. It is possible that there are other liver function markers that are altered with metformin; however, it is more likely that metformin cannot correct liver dysfunction itself. Metformin has been contraindicated in individuals with preexisting conditions that could increase the risk of lactic acidosis, such as lung disease and liver disease (22).

The ER, a cell organelle, is a major site of protein folding and trafficking. When there is an accumulation of unfolded or misfolded proteins in the lumen of the ER, uncoupled protein responses and ER stress occur. These responses inhibit translation and activate the three branches of ER stress: activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6), insulin response element-1 (IRE-1), and protein ki-nase RNA-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase (PERK), each of which are transmembrane proteins that are phosphorylated and activated in response to increased ER stress (23). In the present study, we assessed downstream targets of each of these branches, including Chop, Bip, Dnajb9, Pdia3 and Xbp-1 spliced. We showed that ER stress is increased after burn, as we have previously demonstrated in rodents and patients (6,7). We did not observe a correction in ER stress markers with metformin. It was shown that metformin reduces some, but not all, branches of ER stress in cardiomyocytes as well as cultured hepatocytes (24–26). However, there are little data that illustrate the effect of metformin on hepatic ER stress in vivo. Possibly, ER stress cannot be corrected by metformin in the context of burn, especially at the time points (24-and 48-h postburn) we studied.

Next, we assessed the expression of genes involved in hepatic gluconeogenesis. Metformin is known to lower glucose by inhibiting hepatic gluconeogenesis (15). We measured three of the most common gluconeogenic genes: Pgc1, G6pc and Pck1 (Figure 4). At 24-h postburn, there was an increase in these gluconeogenic gene expressions with burn injury; however, at 48 h, there were no differences. Moreover, metformin did not reduce these gene expressions. It is possible that metformin treatment after burn injury does not reduce glucose by inhibiting gluconeogenesis but rather by increasing glucose utilization. We measured Glut1 and Glut4 expression and found that, at 48-h postburn, metformin increased these glucose transporter expressions significantly (Figures 5E, F).

Because metformin is also known to alleviate hepatic steatosis (17), we quantified the expression of several fatty acid metabolism genes, specifically Acox1, Cd36, Fasn and Scd1 (Figures 5A-D). It is important to note that in all of the metabolic gene expressions we evaluated, the burn injury groups had higher expression than shams, regardless of whether the gene was responsible for synthesis or breakdown of fatty acids. We postulate that this is due to the hypermetabolism that occurs after burn. Metformin further upregulated these expressions, especially after 48 h; Cd36 and Scd1 genes, which are associated with the uptake and synthesis of fat, were further upregulated (50- and 15-fold versus sham, respectively). However, Acox1, a gene responsible for the oxidation of fatty acids, had an even greater increase (100-fold), suggesting that numerous pathways involving fat metabolism were altered with metformin treatment. The discrepancies in the gene expression pattern may affect hepatic phenotype such as triglyceride content (Figure 6). Because hepatic steatosis is known to occur in burn, we expected the increased triglyceride levels in the burn livers. Although this was not statistically significant, we observed a trend toward increased triglyceride in burn livers. Rats that received metformin had decreased triglyceride compared with nontreated rats. These results are in agreement with our gene expression data that Acox1 is significantly increased in metformin-treated burn livers.

What do we think are the mechanisms of metformin? There are several results in this study that showed even detrimental effects of metformin in terms of ER stress and gluconeogenesis at some time points. The possible explanations are not easy. Both ER stress and gluconeogenic gene expressions are increased with metformin. It could be that the observed changes with metformin are a time effect, or it could be that many of the gluconeogenic gene expressions are upregulated when they “sense” high glucose/high FA in the blood. Therefore, if at some point during the first 48 h hepatocytes encounter a lot of these, then it may be around 48 h that the gene expression shoots up. But there seems no real mechanism that is obvious. Our primary concern in this study was that, although there were trends in changes, many did not reach statistical significance. We postulated that metformin possibly exerts its effects not through the liver, but through other organs such as the adipose or the muscle. The main physiological and molecular changes could occur in other organs, and it will be important in future studies to examine extrahepatic tissues. It may also be valuable in the future to study time points beyond 48 h, since the rats sacrificed at 48-h postburn were given an additional dose of metformin, which may be a confounding factor.

Conclusion

We have shown that metformin does not reverse burn-induced hepatic derangements such as ER stress and dysfunction and that there is a possibility that it may improve patient outcome by upregulating hepatic fatty acid metabolism. We also conclude that insulin and metformin act very differently after burn on liver and liver-associated metabolic and morphologic changes.

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no competing interests as defined by Molecular Medicine, or other interests that might be perceived to influence the results and discussion reported in this paper.

References

Jeschke MG, et al. (2011) Long-term persistence of the pathophysiologic response to severe burn injury. PLoS One. 6:e21245.

Jeschke MG, et al. (2008) Pathophysiologic response to severe burn injury. Ann. Surg. 248:387–401.

Jeschke MG, Micak RP, Finnerty CC, Herndon DN. (2007) Changes in liver function and size after a severe thermal injury. Shock. 28:172–7.

Jeschke MG. (2009) The hepatic response to thermal injury: is the liver important for post-burn outcomes? Mol. Med. 15:337–51.

Jeschke MG, Barrow RE, Herndon DN. (2004) Extended hypermetabolic response of the liver in severely burned pediatric patients. Arch. Surg. 139:641–7.

Jeschke MG, et al. (2011) Insulin protects against hepatic damage post-burn. Mol. Med. 17:516–22.

Song J, Finnerty CC, Herndon DN, Boehning D, Jeschke MG. (2009) Severe burn-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress and hepatic damage in mice. Mol. Med. 15:316–20.

Gore DC, Wolf SE, Herndon DN, Wolfe RR. (2003) Metformin blunts stress-induced hyperglycemia after thermal injury. J. Trauma. 54:555–61.

Frayn KN. (1976) Effects of metformin on insulin resistance after injury in the rat. Diabetologia. 12:53–60.

Zhou G, et al. (2001) Role of AMP-activated protein kinase in mechanism of metformin action. J. Clin. Invest. 108:1167–74.

Shaw RJ, et al. (2005) The kinase LKB1 mediates glucose homeostasis in liver and therapeutic effects of metformin. Science. 310:1642–6.

Towler MC, Hardie DG. (2007) AMP-activated protein kinase in metabolic control and insulin signaling. Circ. Res. 100:328–41.

Argaud D, Roth H, Wiernsperger N, Leverve XM. (1993) Metformin decreases gluconeogenesis by enhancing the pyruvate kinase flux in isolated rat hepatocytes. Eur. J. Biochem. 213:1341–8.

Otto M, Breinholt J, Westergaard N. (2003) Metformin inhibits glycogen synthesis and gluconeogenesis in cultured rat hepatocytes. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 5:189–94.

Kim YD, et al. (2008) Metformin inhibits hepatic gluconeogenesis through AMP-activated protein kinase-dependent regulation of the orphan nuclear receptor SHP. Diabetes. 57:306–14.

Yoshida T, et al. (2009) Metformin primarily decreases plasma glucose not by gluconeogenesis suppression but by activating glucose utilization in a non-obese type 2 diabetes Goto-Kakizaki rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 623:141–7.

Lin HZ, et al. (2000) Metformin reverses fatty liver disease in obese, leptin-deficient mice. Nat. Med. 6:998–1003.

Herndon DN, Wilmore DW, Mason AD Jr. (1978) Development and analysis of a small animal model simulating the human post-burn hypermetabolic response. J. Surg. Res. 25:394–403.

Folch J, Lees M, Sloane Stanley GH. (1957) A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipides from animal tissues. J. Biol. Chem. 226:497–509.

Warden SM, et al. (2001) Post-translational modifications of the beta-1 subunit of AMP-activated protein kinase affect enzyme activity and cellular localization. Biochem. J. 354:275–83.

Leffler M, et al. (2007) Insulin attenuates apoptosis and exerts anti-inflammatory effects in endotoxemic human macrophages. J. Surg. Res. 143:398–406.

Eurich DT, et al. (2007) Benefits and harms of antidiabetic agents in patients with diabetes and heart failure: systematic review. BMJ. 335:497.

Ron D, Walter P. (2007) Signal integration in the endoplasmic reticulum unfolded protein response. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 8:519–29.

Liu J, et al. (2010) Endoplasmic reticulum stress involved in the course of lipogenesis in fatty acids-induced hepatic steatosis. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 25:613–8.

Yeh CH, Chen TP, Wang YC, Lin YM, Fang SW. (2010) AMP-activated protein kinase activation during cardioplegia-induced hypoxia/reoxygenation injury attenuates cardiomyocytic apoptosis via reduction of endoplasmic reticulum stress. Mediators Inflamm. 2010:130636.

Quentin T, Steinmetz M, Poppe A, Thoms S. (2012) Metformin differentially activates ER stress signaling pathways without inducing apoptosis. Dis. Model Mech. 5:259–69.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01-GM087285-01 to MG Jeschke), Canadian Institutes of Health Research (123336), the CFI’s Leader’s Opportunity Fund (25407 to MG Jeschke) and the Health Research Grant Program from the Physicians’ Services Incorporated Foundation (to MG Jeschke). We thank the SRI Genomics Core Facility for genotyping the samples.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

YH, AHM, and RK contributed equally to this work.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, and provide a link to the Creative Commons license. You do not have permission under this license to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it.

The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

To view a copy of this license, visit (https://doi.org/creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/)

About this article

Cite this article

Hiyama, Y., Marshall, A.H., Kraft, R. et al. Effects of Metformin on Burn-Induced Hepatic Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress in Male Rats. Mol Med 19, 1–6 (2013). https://doi.org/10.2119/molmed.2012.00330

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2119/molmed.2012.00330