Abstract

Objectives

To i) estimate how large the mortality reductions would be if women were offered screening from age 50 until age 69; ii) to do so using the same trials and participation rates considered by the Canadian Task Force; iii) but to be guided in our analyses by the critical differences between cancer screening and therapeutics, by the time-pattern that characterizes the mortality reductions produced by a limited number of screens, and by the year-by-year mortality data in the appropriate segment of follow-up within each trial; and thereby iv) to avoid the serious underestimates that stem from including inappropriate segments of follow-up, i.e., too soon after study entry and too late after discontinuation of screening.

Methods

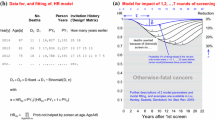

We focused on yearly mortality rate ratios in the follow-up years where, based on the screening regimen employed, mortality deficits would be expected. Because the regimens differed from trial to trial, we did not aggregate the yearly data across trials. To avoid statistical extremes arising from the small numbers of yearly deaths in each trial, we calculated rate ratios for 3-year moving windows.

Results

We were able to extract year-specific data from the reports of five of the trials. The data are limited for the most part by the few rounds of screening. Nevertheless, they suggest that screening from age 50 until age 69 would, at each age from 55 to 74, result in breast cancer mortality reductions much larger than the estimate of 21% that the Canadian Task Force report is based on.

Discussion

By ignoring key features of cancer screening, several of the contemporary analyses have seriously underestimated the impact to be expected from such a program of breast cancer screening.

Résumé

Objectifs

i) Estimer de combien baisserait la mortalité si l’on proposait aux femmes un dépistage du cancer du sein dès 50 ans et jusqu’à 69 ans; ii) procéder en utilisant les mêmes essais et les mêmes taux de participation que ceux examinés par le Groupe d’étude canadien; iii) mais dans notre analyse, nous guider sur les différences essentielles entre le dépistage et les traitements du cancer, sur l’enchaînement chronologique qui caractérise les baisses de mortalité produites par un nombre limité de dépistages, et sur les données de mortalité annuelles dans le segment de suivi approprié à l’intérieur de chaque essai; et donc iv) éviter les sous-estimations graves qui découlent de l’inclusion de segments de suivi inappropriés, c.-à-d. trop tôt après l’entrée dans l’étude et trop tard après l’abandon du dépistage.

Méthode

Nous nous sommes concentrés sur les ratios annuels des taux de mortalité dans les années de suivi où, d’après le régime de dépistage employé, on pourrait s’attendre à des déficits de mortalité. Comme les régimes diffèrent d’un essai à l’autre, nous n’avons pas groupé les données annuelles de chaque essai. Pour éviter les valeurs statistiques extrêmes dues au petit nombre de décès annuels dans chaque essai, nous avons calculé les ratios des taux selon des fenêtres mobiles de trois ans.

Résultats

Nous avons pu extraire des données annuelles dans les rapports de cinq essais. Les données sont limitées pour la plupart par le petit nombre de cycles de dépistage. Néanmoins, elles donnent à penser que le dépistage de 50 à 69 ans résulterait, à chaque âge entre 55 et 74 ans, en une baisse de la mortalité par cancer du sein beaucoup plus importante que l’estimation de 21% sur laquelle se fonde le rapport du Groupe d’étude canadien.

Analyse

En ne tenant pas compte de certaines caractéristiques clés du dépistage du cancer, plusieurs analyses contemporaines sous-estiment gravement l’impact attendu d’un tel programme de dépistage du cancer du sein.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for Breast Cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Ann Intern Med 2009;151:716–26.

Independent UK Panel on Breast Cancer Screening. The benefits and harms of breast cancer screening: An independent review. Lancet 2012;380(9855):1778–86.

Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care, Tonelli M, Connor Gorber S, Joffres M, Dickinson J, Singh H, et al. Recommendations on screening for breast cancer in average-risk women aged 40–74 years. CMAJ 2011;183(17):1991–2001.

Miettinen OS, Henschke CI, Pasmantier MW, Smith JP, Libby DM, Yankelevitz DF. Mammographic screening: No reliable supporting evidence? Lancet 2002;359(9304):404–5.

Miettinen OS, Karp I. Epidemiological Research: An Introduction. New York, NY: Springer, 2012; 81

Morrison AS. Screening in Chronic Disease, First Edition. New York: Oxford University Press, 1985.

Caro J. Screening for breast cancer in Québec: Estimates of health effects and of costs. Montreal: CÉTS, 1990;24. Available at: https://doi.org/www.aetmis.gouv.qc.ca/site/en_publications_liste.phtml (Accessed January 7, 2012).

Hu P, Zelen M. Planning clinical trials to evaluate early detection programs. Biometrika 1997;84:817–29.

Hu P, Zelen M. Planning of randomized early detection trials. Stat Methods Med Res 2004;13(6):491–506.

Hanley JA. Analysis of mortality data from cancer screening studies: Looking in the right window. Epidemiology 2005;16:786–90.

Baker SG, Kramer BS, Prorok PC. Early reporting for cancer screening trials. J Med Screen 2008;15:122–29.

Hanley JA. Mortality reductions produced by sustained prostate cancer screening have been underestimated. J Med Screen 2010;17(3):147–51.

Hanley JA. Measuring mortality reductions in cancer screening trials. Epidemiol Rev 2011;33(1):36–45.

Shapiro S. Evidence on screening for breast cancer from a randomized trial. Cancer 1977;39(6 Suppl):2772–82.

Andersson I, Aspegren K, Janzon L, Landberg T, Lindholm K, Linell F, et al. Mammographic screening and mortality from breast cancer: The Malmö mammographic screening trial. BMJ 1988;297(6654):943–48.

Tabár L, Fagerberg CJ, Gad A, Baldetorp L, Holmberg LH, Gröntoft O, et al. Reduction in mortality from breast cancer after mass screening with mammography. Randomised trial from the Breast Cancer Screening Working Group of the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare. Lancet 1985;1(8433):829–32.

Frisell J, Lidbrink E, Hellström L, Rutqvist LE. Followup after 11 years–Update of mortality results in the Stockholm mammographic screening trial. Breast Cancer Res Treat 1997;45(3):263–70.

Bjurstam N, Björneld L, Warwick J, Sala E, Duffy SW, Nyström L, et al. The Gothenburg Breast Screening Trial. Cancer 2003;97:2387–96.

Miller AB, To T, Baines CJ, Wall C. Canadian National Breast Screening Study-2: 13-year results of a randomized trial in women aged 50–59 years. J Natl Cancer Inst 2000;92(18):1490–99.

Fitzpatrick-Lewis D, Hodgson N, Ciliska D, Peirson L, Gauld M, Yun Liu Y. Breast cancer screening. Available at: https://doi.org/www.ephpp.ca/pdf/breast_cancer_2011_systematic_review_ENG.pdf (Accessed July 26, 2012).

Breslow NE, Day NE. Statistical Methods in Cancer Research. Volume II–The Design and Analysis of Cohort Studies. Lyons, France: IARC Scientific Publications No. 82., 1987.

Liu Z, Hanley JA, Strumpf EC. Projecting the yearly mortality reductions due to a cancer screening programme. J Med Screen [2013 Sep 18. Epub ahead of print].

Marcus PM, Bergstralh EJ, Fagerstrom RM, Williams DE, Fontana R, Taylor WF, Prorok PC. Lung cancer mortality in the Mayo Lung Project: Impact of extended follow-up. J Natl Cancer Inst 2000;92(16):1308–16.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Acknowledgements: This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

Conflict of Interest: None to declare.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hanley, J.A., McGregor, M., Liu, Z. et al. Measuring the Mortality Impact of Breast Cancer Screening. Can J Public Health 104, e437–e442 (2013). https://doi.org/10.17269/cjph.104.4099

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.17269/cjph.104.4099