Abstract

OBJECTIVES: Although timely access to health care is a top priority, a burgeoning body of research highlights the important role of neighbourhood environments on unmet health care needs. This study aimed to examine an association between perceptions of neighbourhood availability of health care services and experience of unmet health care needs by gender in an urban city setting.

METHODS: A total of 2338 participants from the Neighbourhood Effects on Health and Well-being (NEHW) study, between 25 and 64 years of age and dwelling in the City of Toronto, Ontario, Canada, were included in the analyses. Four different logistic regression models stratified by gender were used to examine the relationship between neighbourhood health care availability and unmet health care need as well as the impact of neighbourhood perception of health care availability on the three different types of unmet needs.

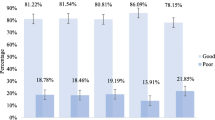

RESULTS: Perceived health care availability was associated with higher likelihood of experiencing unmet health care needs in both women and men (women = OR: 1.58, 95% CI: 1.09–2.28; men = OR: 1.92, 95% CI: 1.23–2.99). In addition, perceived health care availability was associated with barrier-and wait times-related unmet health care need among women (OR: 1.83, 95% CI: 1.13–2.97; OR: 1.93, 95% CI: 1.10–3.40 respectively), and personal choice- and wait times-related unmet need among men (OR: 1.99, 95% CI: 1.10–3.58).

CONCLUSION: Individuals’ perception of health care availability plays a crucial role in the experience of unmet health care needs, suggesting the importance of community-based policy development for improving physical conditions and the social aspect of health care services.

Résumé

OBJECTIFS: L’accès rapide aux soins de santé est une priorité absolue, mais un corpus de recherche grandissant fait ressortir l’importance des environnements de quartiers pour combler les besoins de soins de santé insatisfaits. Notre étude visait à examiner l’association entre les perceptions de la disponibilité de services de soins de santé dans le quartier et l’expérience des besoins de soins de santé insatisfaits, selon le sexe, dans un milieu urbain.

MÉTHODE: Nos analyses ont porté sur 2 338 participants de l’étude Neighbourhood Effects on Health and Well-being (NEHW) âgés de 25 à 64 ans et vivant à Toronto (Ontario) au Canada. Nous avons utilisé quatre modèles de régression logistique stratifiés selon le sexe pour examiner la relation entre la disponibilité des soins de santé dans le quartier et les besoins de soins de santé insatisfaits, ainsi que l’impact de la perception de la disponibilité des soins de santé dans le quartier sur les trois types de besoins insatisfaits.

RÉSULTATS: La disponibilité perçue des soins de santé était associée à une probabilité accrue d’éprouver des besoins de soins de santé insatisfaits, tant chez les femmes que chez les hommes (femmes = RC: 1,58, IC de 95%: 1,09–2,28; hommes = RC: 1,92, IC de 95%: 1,23–2,99). En outre, la disponibilité perçue des soins de santé était associée à des besoins de soins de santé insatisfaits liés aux barrières et aux temps d’attente chez les femmes (RC: 1,83, IC de 95%: 1,13–2,97; RC: 1,93, IC de 95%: 1,10–3,40, respectivement), et à des besoins insatisfaits liés aux choix personnels et aux temps d’attente chez les hommes (RC: 1,99, IC de 95%: 1,10–3,58).

CONCLUSION: La perception individuelle de la disponibilité des soins de santé joue un rôle décisif dans l’expérience des besoins de soins de santé insatisfaits, ce qui indique l’importance d’élaborer des politiques communautaires pour améliorer les conditions matérielles et l’aspect social des services de soins de santé.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Hutchison B. Disparities in healthcare access and use: Yackety-yack, yackety-yack. Healthc Policy 2007;3(2):10–13. PMID: 19305775.

Sibley LM, Glazier RH. Reasons for self-reported unmet healthcare needs in Canada: A population-based provincial comparison. Healthcare Policy 2009;5(1):87–101. PMID: 20676253.

Devaux M. Income-related inequalities and inequities in health care services utilisation in 18 selected OECD countries. Eur J Health Econ 2013;16(1):21–33. PMID: 24337894. doi: 10.1007/s10198-013-0546-4.

Veugelers PJ, Yip AM. Socioeconomic disparities in health care use: Does universal coverage reduce inequalities in health? J Epidemiol Community Health 2003;57(6):424–28. PMID: 12775787. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.6.424.

Curtis LJ, MacMinn WJ. Health care utilization in Canada: Twenty-five years of evidence. Can Public Policy 2008;34(1):65–87. doi: 10.3138/cpp.34.1.065.

Birch S, Abelson J. Is reasonable access what we want? Implications of, and challenges to, current Canadian policy on equity in health care. Int J Health Serv 1993;23(4):629–53. doi: 10.2190/K18V-T33F-1VC4-14RM.

Maddison A, Asada Y, Urquhart R. Inequity in access to cancer care: A review of the Canadian literature. Cancer Causes Control 2011;22(3):359–66. PMID: 21221758. doi: 10.1007/s10552-010-9722-3.

Dunlop S, Coyte PC, McIsaac W. Socio-economic status and the utilisation of physicians’ services: Results from the Canadian National Population Health Survey. Soc Sci Med 2000;51(1):123–33. PMID: 10817475. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00424-4.

Bissonnette L, Wilson K, Bell S, Shah TI. Neighbourhoods and potential access to health care: The role of spatial and aspatial factors. Health Place 2012;18(4):841–53. PMID: 22503565. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2012.03.007.

Diez Roux AV. Investigating neighborhood and area effects on health. Am J Public Health 2001;91(11):1783–89. PMID: 11684601. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.91.11.1783.

Poortinga W, Dunstan F, Fone D. Perceptions of the neighbourhood environment and self rated health: A multilevel analysis of the Caerphilly Health and Social Needs Study. BMC Public Health 2007;7(1):285. PMID: 17925028. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-285.

Ross NA, Tremblay SS, Graham K. Neighbourhood influences on health in Montreal, Canada. Soc Sci Med 2004;59(7):1485–94. PMID: 15246176. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.01.016.

Ellen IG, Mijanovich T, Dillman K-N. Neighborhood effects on health: Exploring the links and assessing the evidence. J Urban Aff 2001;23(3–4):391–408. doi: 10.1111/0735-2166.00096.

Lévesque J-F. Unmet Health Care Needs: A Reflection of the Accessibility of Primary Care Services? Montreal, QC: Agence de la santé et des Services sociaux de Montréal, Direction de santé publique, 2008.

Nelson CH, Park J. The nature and correlates of unmet health care needs in Ontario, Canada. Soc Sci Med 2006;62(9):2291–300. PMID: 16431003. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.10.014.

Zygmunt A, Asada Y, Burge F. Is team-based primary care associated with less access problems and self-reported unmet need in Canada? Int J Health Serv 2015;pii:0020731415595547. PMID: 26182942. doi: 10.1177/0020731415595547.

Asada Y, Kephart G. Understanding different methodological approaches to measuring inequity in health care. Int J Health Serv 2011;41(2):195–207. doi: 10.2190/HS.41.2.a.

Allin S, Grignon M, Le Grand J. Subjective unmet need and utilization of health care services in Canada: What are the equity implications? Soc Sci Med 2010;70(3):465–72. PMID: 19914759. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.10.027.

Weden MM, Carpiano RM, Robert SA. Subjective and objective neighborhood characteristics and adult health. Soc Sci Med 2008;66(6):1256–70. PMID: 18248865. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.11.041.

Brondeel R, Weill A, Thomas F, Chaix B. Use of healthcare services in the residence and workplace neighbourhood: The effect of spatial accessibility to healthcare services. Health Place 2014;30:127–33. PMID: 25262490. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2014.09.004.

Law M, Wilson K, Eyles J, Elliott S, Jerrett M, Moffat T, et al. Meeting health need, accessing health care: The role of neighbourhood. Health Place 2005;11(4):367–77. PMID: 15886144. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2004.05.004.

Kravet SJ, Shore AD, Miller R, Green GB, Kolodner K, Wright SM. Health care utilization and the proportion of primary care physicians. Am J Med 2008;121(2):142–48. PMID: 18261503. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.10.021.

Litaker D, Love TE. Health care resource allocation and individuals’ health care needs: Examining the degree of fit. Health Policy 2005;73(2):183–93. PMID: 15978961. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2004.11.010.

Yip AM, Kephart G, Veugelers PJ. Individual and neighbourhood determinants of health care utilization. Implications for health policy and resource allocation. Can J Public Health 2002;93(4):303–7. PMID: 12154535.

O’Campo P, Wheaton B, Nisenbaum R, Glazier RH, Dunn JR, Chambers C. The Neighbourhood Effects on Health and Well-being (NEHW) study. Health Place 2015;31:65–74. PMID: 25463919. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2014.11.001.

Andersen RM. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: Does it matter? J Health Soc Behav 1995;36:1–10. doi: 10.2307/2137284.

Hox JJ, Moerbeek M, van de Schoot R. Multilevel Analysis: Techniques and Applications. New York, NY: Routledge, 2010.

Kirby JB, Kaneda T. Neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage and access to health care. J Health Soc Behav 2005;46(1):15–31. PMID: 15869118. doi: 10.1177/002214650504600103.

Fisher ES, Wennberg JE, Stukel TA, Skinner JS, Sharp SM, Freeman JL, et al. Associations among hospital capacity, utilization, and mortality of US Medicare beneficiaries, controlling for sociodemographic factors. Health Serv Res 2000;34(6):1351–62. PMID: 10654835.

Fleury M-J, Grenier G, Bamvita J-M, Perreault M, Kestens Y, Caron J. Comprehensive determinants of health service utilisation for mental health reasons in a Canadian catchment area. Int J Equity Health 2012;11(1):20. PMID: 22469459. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-11-20.

Leaf PJ, Livingston MM, Tischler GL, Weissman MM, Holzer CE III, Myers JK. Contact with health professionals for the treatment of psychiatric and emotional problems. Med Care 1985;23:1322–37. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198512000-00002.

Lebel A, Pampalon R, Villeneuve P. A multi-perspective approach for defining neighbourhood units in the context of a study on health inequalities in the Quebec City region. Int J Health Geogr 2007;6(1):27. PMID: 17615065. doi: 10. 1186/1476-072X-6-27.

Bernard P, Charafeddine R, Frohlich KL, Daniel M, Kestens Y, Potvin L. Health inequalities and place: A theoretical conception of neighbourhood. Soc Sci Med 2007;65(9):1839–52. PMID: 17614174. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.05.037.

Wen M, Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT. Objective and perceived neighborhood environment, individual SES and psychosocial factors, and self-rated health: An analysis of older adults in Cook County, Illinois. Soc Sci Med 2006;63(10):2575–90. PMID: 16905230. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.06.025.

Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW. Seeing disorder: Neighborhood stigma and the social construction of broken windows. Soc Psychol Q 2004;67(4):319–42. doi: 10.1177/019027250406700401.

Burke J, O’Campo P, Salmon C, Walker R. Pathways connecting neighborhood influences and mental well-being: Socioeconomic position and gender differences. Soc Sci Med 2009;68(7):1294–304. PMID: 19217704. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.01.015.

Nowatzki N, Grant KR. Sex is not enough: The need for gender-based analysis in health research. Health Care Women Int 2011;32(4):263–77. PMID: 21409661. doi: 10.1080/07399332.2010.519838.

Bryant T, Leaver C, Dunn J. Unmet healthcare need, gender, and health inequalities in Canada. Health Policy 2009;91(1):24-32. PMID: 19070930. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2008.11.002.

Cavalieri M. Geographical variation of unmet medical needs in Italy: A multivariate logistic regression analysis. Int J Health Geogr 2013;12:27. PMID: 23663530. doi: 10.1186/1476-072X-12-27.

Gany F, Thiel de Bocanegra H. Overcoming barriers to improving the health of immigrant women. J Am Med Womens Assoc (1972) 1996;51(4):155–60. PMID: 8840732.

Salganicoff A. Medicaid and managed care: Implications for low-income women. J Am Med Womens Assoc (1972) 1997;52(2):78–80. PMID: 9127998.

Diamant AL, Hays RD, Morales LS, Ford W, Calmes D, Asch S, et al. Delays and unmet need for health care among adult primary care patients in a restructured urban public health system. Am J Public Health 2004;94(5):783–89. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.94.5.783.

Kaplan DH, Douzet F. Research in ethnic segregation III: Segregation outcomes. Urban Geogr 2011;32(4):589–605. doi: 10.2747/0272-3638.32.4.589.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Acknowledgements: This research was funded by Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Grant MOP-84439 and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council Grant 410-2007-1499. At the time of the study, Drs. Hwang, Guilcher and Mclsaac were funded by a CIHR Strategic Training Initiative in Health Research [ACHIEVE] post-doctoral fellowship (Grant #96566) and the Centre for Urban Health Solutions (formerly the Centre for Research on Inner City Health). Dr. Glazier is supported as a Clinician Scientist in the Department of Family and Community Medicine at St. Michael’s Hospital and at the University of Toronto.

Conflict of Interest: None to declare.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hwang, J., Guilcher, S.J.T., McIsaac, K.E. et al. An examination of perceived health care availability and unmet health care need in the City of Toronto, Ontario, Canada. Can J Public Health 108, e7–e13 (2017). https://doi.org/10.17269/CJPH.108.5715

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.17269/CJPH.108.5715