Abstract

Background

Despite advances in enhanced surgical recovery programs, strategies limiting postoperative inpatient opioid exposure have not been optimized for pancreatic surgery. The primary aims of this study were to analyze the magnitude and variations in post-pancreatectomy opioid administration and to characterize predictors of low and high inpatient use.

Methods

Clinical characteristics and inpatient oral morphine equivalents (OMEs) were downloaded from electronic records for consecutive pancreatectomy patients at a high-volume institution between March 2016 and August 2017. Regression analyses identified predictors of total OMEs as well as highest and lowest quartiles.

Results

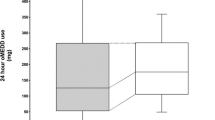

Pancreatectomy was performed for 158 patients (73% pancreaticoduodenectomy). Transversus abdominus plane (TAP) block was performed for 80% (n = 127) of these patients, almost always paired with intravenous patient-controlled analgesia (IV-PCA), whereas 15% received epidural alone. All the patients received scheduled non-opioid analgesics (median, 2). The median total OME administered was 423 mg (range 0–4362 mg). Higher total OME was associated with preoperative opioid prescriptions (p < 0.001), longer hospital length of stay (LOS; p < 0.001), and no epidural (p = 0.006). The lowest and best quartile cutoff was 180 mg of OME or less, whereas the highest and worst quartile cutoff began at 892.5 mg. After adjustment for inpatient team, only epidural use [odds ratio (OR) 0.3; p = 0.04] predicted lowest-quartile OME. Preoperative opioid prescriptions (OR 8.1; p < 0.001), longer operative time (OR 3.4; p = 0.05), and longer LOS (OR 1.1; p = 0.007) predicted highest-quartile OME.

Conclusions

Preoperative opioid prescriptions and longer LOS were associated with increased inpatient OME, whereas epidural use reduced inpatient OME. Understanding the predictors of inpatient opioid use and the variables predicting the lowest and highest quartiles can inform decision-making regarding preoperative counseling, regional anesthetic block choice, and novel inpatient opioid weaning strategies to reduce initial postoperative opioid exposure.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Chen LH, Hedegaard H, Warner M. Drug-poisoning deaths involving opioid analgesics: United States, 1999–2011. NCHS Data Brief. 2014(166):1–8.

Bicket MC, Long JJ, Pronovost PJ, Alexander GC, Wu CL. Prescription opioid analgesics commonly unused after surgery: a systematic review. JAMA Surg. 2017;152:1066–71.

Feinberg AE, Chesney TR, Srikandarajah S, Acuna SA, McLeod RS, Best Practice in Surgery G. Opioid use after discharge in postoperative patients: a systematic review. Ann Surg. 2018;267:1056–62.

Dart RC, Surratt HL, Cicero TJ, et al. Trends in opioid analgesic abuse and mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:241–8.

Clarke H, Soneji N, Ko DT, Yun L, Wijeysundera DN. Rates and risk factors for prolonged opioid use after major surgery: population-based cohort study. BMJ. 2014;348:g1251.

Soneji N, Clarke HA, Ko DT, Wijeysundera DN. Risks of developing persistent opioid use after major surgery. JAMA Surg. 2016;151:1083–4.

Brummett CM, Waljee JF, Goesling J, et al. New persistent opioid use after minor and major surgical procedures in US adults. JAMA Surg. 2017;152:e170504.

Lee JS, Hu HM, Edelman AL, et al. New persistent opioid use among patients with cancer after curative-intent surgery. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:4042–9.

Tuminello S, Schwartz RM, Liu B, et al. Opioid use after open resection or video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery for early-stage lung cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2018.

Chen EY, Marcantonio A, Tornetta P III. Correlation between 24-hour predischarge opioid use and amount of opioids prescribed at hospital discharge. JAMA Surg. 2018;153:e174859.

Stafford C, Francone T, Roberts PL, Ricciardi R. What factors are associated with increased risk for prolonged postoperative opioid usage after colorectal surgery? Surg Endosc. 2018;32:3557–61.

Hwang RF, Wang H, Lara A, et al. Development of an integrated biospecimen bank and multidisciplinary clinical database for pancreatic cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:1356–66.

Denbo JW, Bruno M, Dewhurst W, et al. Risk-stratified clinical pathways decrease the duration of hospitalization and costs of perioperative care after pancreatectomy. Surgery. 2018;164:424–31.

Schwarz L, Bruno M, Parker NH, et al. Active surveillance for adverse events within 90 days: the standard for reporting surgical outcomes after pancreatectomy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:3522–9.

Denbo JW, Slack RS, Bruno M, et al. Selective perioperative administration of pasireotide is more cost-effective than routine administration for pancreatic fistula prophylaxis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2017;21:636–46.

Strasberg SM, Linehan DC, Hawkins WG. The accordion severity grading system of surgical complications. Ann Surg. 2009;250:177–86.

Wente MN, Bassi C, Dervenis C, et al. Delayed gastric emptying (DGE) after pancreatic surgery: a suggested definition by the International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS). Surgery. 2007;142:761–8.

Bassi C, Marchegiani G, Dervenis C, et al. The 2016 update of the International Study Group (ISGPS) definition and grading of postoperative pancreatic fistula: 11 years after. Surgery. 2017;161:584–91.

Newhook TE, Vreeland TJ, Dewhurst WL, et al. Clinical factors associated with practice variation in discharge opioid prescriptions after pancreatectomy. Ann Surg. 2018. November 29 epub ahead of print.

George MJ. The site of action of epidurally administered opioids and its relevance to postoperative pain management. Anaesthesia. 2006;61:659–64.

Kane S. Opioid (opiate) equianagesia conversion calculator. Retrieved 10 June 2018 at ClinCalc: http://clincalc.com/opioids.

American Pain Society. Principles of Analgesic Use in the Treatment of Acute Pain and Cancer Pain. 6th ed. American Pain Society, Glenview, IL, 2008.

Pereira J, Lawlor P, Vigano A, Dorgan M, Bruera E. Equianalgesic dose ratios for opioids: a critical review and proposals for long-term dosing. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2001;22:672–87.

Anderson R, Saiers JH, Abram S, Schlicht C. Accuracy in equianalgesic dosing: conversion dilemmas. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2001;21:397–406.

Patanwala AE, Duby J, Waters D, Erstad BL. Opioid conversions in acute care. Ann Pharmacother. 2007;41:255–66.

Shah A, Hayes CJ, Martin BC. Characteristics of initial prescription episodes and likelihood of long-term opioid use–United States, 2006–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:265–9.

Holte K, Kehlet H. Effect of postoperative epidural analgesia on surgical outcome. Minerva Anestesiol. 2002;68:157–61.

Kehlet H, Holte K. Effect of postoperative analgesia on surgical outcome. Br J Anaesth. 2001;87:62–72.

Aloia TA, Zimmitti G, Conrad C, Gottumukalla V, Kopetz S, Vauthey JN. Return to intended oncologic treatment (RIOT): a novel metric for evaluating the quality of oncosurgical therapy for malignancy. J Surg Oncol. 2014;110:107–14.

Kim BJ, Aloia TA. What Is “enhanced recovery” and how can i do it? J Gastrointest Surg. 2018;22:164–71.

Shah DR, Brown E, Russo JE, et al. Negligible effect of perioperative epidural analgesia among patients undergoing elective gastric and pancreatic resections. J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;17:660–7.

Marret E, Remy C, Bonnet F. Postoperative Pain Forum G: meta-analysis of epidural analgesia versus parenteral opioid analgesia after colorectal surgery. Br J Surg. 2007;94:665–73.

Bartha E, Carlsson P, Kalman S. Evaluation of costs and effects of epidural analgesia and patient-controlled intravenous analgesia after major abdominal surgery. Br J Anaesth. 2006;96:111–7.

Konigsrainer I, Bredanger S, Drewel-Frohnmeyer R, et al. Audit of motor weakness and premature catheter dislodgement after epidural analgesia in major abdominal surgery. Anaesthesia 2009;64:27–31.

Sugimoto M, Nesbit L, Barton JG, Traverso LW. Epidural anesthesia dysfunction is associated with postoperative complications after pancreatectomy. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2016;23:102–9.

Axelrod TM, Mendez BM, Abood GJ, Sinacore JM, Aranha GV, Shoup M. Perioperative epidural may not be the preferred form of analgesia in select patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy. J Surg Oncol. 2015;111:306–10.

Aloia TA, Kim BJ, Segraves-Chun YS, et al. A randomized controlled trial of postoperative thoracic epidural analgesia versus intravenous patient-controlled analgesia after major hepatopancreatobiliary surgery. Ann Surg. 2017;266:545–54.

Ladha KS, Gagne JJ, Patorno E, et al. Opioid overdose after surgical discharge. JAMA. 2018;320:502–4.

Repeat quadratus lumborum block to reduce opioid need in patients after pancreatic surgery. Retrieved 21 December 2018 at https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT03745794.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Newhook, T.E., Dewhurst, W.L., Vreeland, T.J. et al. Inpatient Opioid Use After Pancreatectomy: Opportunities for Reducing Initial Opioid Exposure in Cancer Surgery Patients. Ann Surg Oncol 26, 3428–3435 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-019-07528-z

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-019-07528-z