Abstract

Background

Although major cancer surgery at a high-volume hospital is associated with lower postoperative mortality, the use of such hospitals may not be equally distributed.

Objective

Our aim was to study socioeconomic and racial differences in cancer surgery at Commission on Cancer (CoC)-accredited high-volume hospitals.

Methods

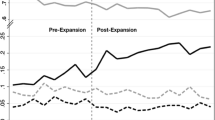

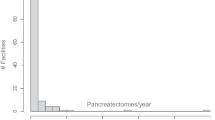

The National Cancer Database (NCDB) was used to identify patients undergoing surgery for colon, esophageal, liver, and pancreatic cancer from 2003 to 2012. Annual hospital volume for each cancer was categorized using quartiles of patient volume. Patient-level predictors of surgery at a high-volume hospital, trends in the use of a high-volume hospital, and adjusted likelihood of surgery at a high-volume hospital in 2012 versus 2003 were analyzed.

Results

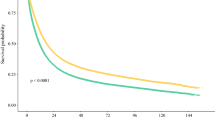

African American patients were less likely to undergo surgery at a high-volume hospital for esophageal (odds ratio [OR] 0.59, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.49–0.73) and pancreatic cancer (OR 0.83, 95% CI 0.74–0.92), while uninsured patients and those residing in low educational attainment zip codes were less likely to undergo surgery at a high-volume hospital for esophageal, liver, and pancreatic cancer. In 2012, African Americans, uninsured patients, and those from low educational attainment zip codes were no more likely to undergo surgery at a high-volume hospital than in 2003 for any cancer type. These differences were not seen in colon cancer patients, for whom significant regionalization was not seen.

Conclusions

Differences in the use of CoC-accredited high-volume hospitals for major cancer surgery were seen nationwide and persisted over the duration of the study. Strategies to increase referrals and/or access to high-volume hospitals for African American and socioeconomically disadvantaged patients should be explored.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Birkmeyer JD, Siewers AE, Finlayson EV, et al. Hospital volume and surgical mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1128–37.

Begg CB, Cramer LD, Hoskins WJ, Brennan MF. Impact of hospital volume on operative mortality for major cancer surgery. JAMA. 1998;280:1747–51.

Wouters MW, Wijnhoven BP, Karim-Kos HE, et al. High-volume versus low-volume for esophageal resections for cancer: the essential role of case-mix adjustments based on clinical data. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:80–7.

Schrag D, Cramer LD, Bach PB, Cohen AM, Warren JL, Begg CB. Influence of hospital procedure volume on outcomes following surgery for colon cancer. JAMA. 2000;284:3028–35.

Birkmeyer JD, Finlayson SR, Tosteson AN, Sharp SM, Warshaw AL, Fisher ES. Effect of hospital volume on in-hospital mortality with pancreaticoduodenectomy. Surgery. 1999;125:250–6.

Finks JF, Osborne NH, Birkmeyer JD. Trends in hospital volume and operative mortality for high-risk surgery. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2128–37.

Learn PA, Bach PB. A decade of mortality reductions in major oncologic surgery: the impact of centralization and quality improvement. Med Care. 2010;48:1041–9.

Stitzenberg KB, Meropol NJ. Trends in centralization of cancer surgery. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:2824–31.

Bilimoria KY, Bentrem DJ, Stewart AK, Winchester DP, Ko CY. Comparison of commission on cancer-approved and -nonapproved hospitals in the United States: implications for studies that use the National Cancer Data Base. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4177–81.

Stitzenberg KB, Sigurdson ER, Egleston BL, Starkey RB, Meropol NJ. Centralization of cancer surgery: implications for patient access to optimal care. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4671–8.

Liu JH, Zingmond DS, McGory ML, et al. Disparities in the utilization of high-volume hospitals for complex surgery. JAMA. 2006;296:1973–80.

Epstein AJ, Gray BH, Schlesinger M. Racial and ethnic differences in the use of high-volume hospitals and surgeons. Arch Surg. 2010;145:179–86.

US Census Bureau. 2000 Census of Population and Housing. https://www.census.gov/prod/cen2000/doc/sf2.pdf.

Kronebusch K, Gray BH, Schlesinger M. Explaining racial/ethnic disparities in use of high-volume hospitals: decision-making complexity and local hospital environments. Inquiry 2014;51

Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development, Healthcare Atlas. http://gis.oshpd.ca.gov/atlas/topics/use/volumes.

Finlayson SR, Birkmeyer JD, Tosteson AN, Nease RF, Jr. Patient preferences for location of care: implications for regionalization. Med Care. 1999;37:204–9.

Huang LC, Ma Y, Ngo JV, Rhoads KF. What factors influence minority use of National Cancer Institute-designated cancer centers? Cancer. 2014;120:399–407.

Institute of Medicine. Delivering High-Quality Cancer Care: Charting a New Course for a System in Crisis. Washington DC: National Academies Press; 2013

Fortney J RK, Warren J. comparing alternative methods of measuring geographic access to health services. Health Serv Outcomes Res Methodol. 2000;1:173–84.

Acknowledgment

The data used in this study are derived from a de-identified NCDB file. The American College of Surgeons and the CoC have not verified and are not responsible for the analytic or statistical methodology employed, or the conclusions drawn from these data by the investigators.

Funding

This study was supported in part by the Mayo Clinic Robert D. and Patricia E. Kern Center for the Science of Health Care Delivery.

Disclosures

Nabil Wasif, David Etzioni, Elizabeth B. Habermann, Amit Mathur, Barbara A. Pockaj, Richard J. Gray, and Yu-Hui Chang declare no financial disclosures or conflicts of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wasif, N., Etzioni, D., Habermann, E.B. et al. Racial and Socioeconomic Differences in the Use of High-Volume Commission on Cancer-Accredited Hospitals for Cancer Surgery in the United States. Ann Surg Oncol 25, 1116–1125 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-018-6374-0

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-018-6374-0