Abstract

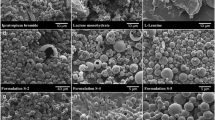

Ciprofloxacin is a broad-spectrum antibiotic for treatment of pulmonary diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and cystic fibrosis. The purpose of this work was to rationally study the spray drying of ciprofloxacin in order to identify the formulation and operating conditions that lead to a product with aerodynamic properties appropriate for dry powder inhalation. A 24 − 1 fractional factorial design was applied to investigate the effect of selected variables (i.e., ciprofloxacin hydrochloride (CIP) concentration, drying air inlet temperature, feed flow rate, and atomization air flow rate) on several product and process parameters (i.e., particle size, aerodynamic diameter, moisture content, densities, porosity, powder flowability, outlet temperature, and process yield) and to determine an optimal condition. The studied factors had a significant effect on the evaluated responses (higher p value 0.0017), except for the moisture content (p value > 0.05). The optimal formulation and operating conditions were as follows: CIP concentration 10 mg/mL, drying air inlet temperature 110°C, feed volumetric flow rate 3.0 mL/min, and atomization air volumetric flow rate 473 L/h. The product obtained under this set had a particle size that guarantees access to the lung, a moisture content acceptable for dry powder inhalation, fair flowability, and high process yield. The PDRX and SEM analysis of the optimal product showed a crystalline structure and round and dimpled particles. Moreover, the product was obtained by a simple and green spray drying method.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Siddiqi A, Sethi S. Optimizing antibiotic selection in treating COPD exacerbations. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2008;3:31–44.

WHO. World Health Organization. Chronic respiratory diseases. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). http://www.who.int/respiratory/copd/en/ (Accessed 19 September 2017).

Sethi S, Murphy T. Bacterial infection in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in 2000. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2001;14:336–63.

Emerson J, Rosenfeld M, McNamara S, Ramsey B, Gibson R. Pseudomonas aeruginosa and other predictors of mortality and morbidity in young children with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2002;34:91–100.

Döring G, Flume P, Heijerman H, Elborn J. Treatment of lung infection in patients with cystic fibrosis: current and future strategies. J Cyst Fibros. 2012;11:461–79.

Eller J, Ede A, Schaberg T, Niederman M, Mauch H, Lode H. Infective exacerbations of chronic bronchitis: relation between bacteriologic etiology and lung function. Chest. 1998;113:1542–8.

Redmond A, Sweeney L, Macfarland M, Mitchell M, Daggett S, Kubin R. Oral ciprofloxacin in the treatment of pseudomonas exacerbations of pediatric cystic fibrosis: clinical efficacy and safety evaluation using magnetic resonance image scanning. J Int Med Res. 1998;26:304–12.

WHO, World Health Organization. Model formulary. 2008. http://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/44053 (Accessed 19 Sept 2017).

Kontou P, Chatzika K, Pitsiou G, Stanopoulos I, Argyropoulou-Pataka P, Kioumis I. Pharmacokinetics of ciprofloxacin and its penetration into bronchial secretions of mechanically ventilated patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:4149–53.

Cipolla D. Will pulmonary drug delivery for systemic application ever fulfill its rich promise? Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2016;13:1337–40.

Dimer F, de Souza Carvalho-Wodarz C, Haupenthal J, Hartmann R, Lehr C. Inhalable clarithromycin microparticles for treatment of respiratory infections. Pharm Res. 2015;32:3850–61.

Devarajan P, Jain S. Targeted drug delivery: concepts and design. New York: Springer; 2015. p. 22–3.

Adi H, Young P, Chan H, Stewart P, Agus H, Traini D. Cospray dried antibiotics for dry powder lung delivery. J Pharm Sci. 2008;97:3356–66.

Pilcer G, De Bueger V, Traina K, Traore H, Sebti T, Vanderbist F, et al. Carrier-free combination for dry powder inhalation of antibiotics in the treatment of lung infections in cystic fibrosis. Int J Pharm. 2013;451:112–20.

Alagusundaram M, Deepthi N, Ramkanth S, Angalaparameswari S, Saleem T, Gnanaprakash T, et al. Dry powder inhalers - an overview. Int J Res Pharm Sci. 2010;1:34–42.

Sosnik A, Seremeta K. Advantages and challenges of the spray-drying technology for the production of pure drug particles and drug-loaded polymeric carriers. Adv Colloid Interf Sci. 2015;223:40–54.

Seville P, Li H, Learoyd T. Spray-dried powders for pulmonary drug delivery. Crit Rev Ther Drug Carrier Syst. 2007;24:307–60.

Vicente J, Pinto J, Menezes J, Gaspar F. Fundamental analysis of particle formation in spray drying. Powder Technol. 2013;247:1–7.

Adi H, Young P, Chan H, Agus H, Traini D. Co-spray-dried mannitol–ciprofloxacin dry powder inhaler formulation for cystic fibrosis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2010;40:239–47.

Osman R, Kan P, Awad G, Mortada N, EL-Shamy A, Alpar O. Spray dried inhalable ciprofloxacin powder with improved aerosolisation and antimicrobial activity. Int J Pharm. 2013;449:44–58.

Yang Y, Tsifansky M, Shin S, Lin Q, Yeo Y. Mannitol-guided delivery of ciprofloxacin in artificial cystic fibrosis mucus model. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2011;108:1441–9.

Ely L, Roa W, Finlay W, Lobenberg R. Effervescent dry powder for respiratory drug delivery. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2007;65:346–53.

Karimi K, Pallagi E, Szabó-Révész P, Csóka I, Ambrus R. Development of a microparticle-based dry powder inhalation formulation of ciprofloxacin hydrochloride applying the quality by design approach. Drug Des Dev Ther. 2016;10:3331–43.

Cayli Y, Sahin S, Buttini F, Balducci A, Montanari A, Vural I, et al. Dry powders for the inhalation of ciprofloxacin or levofloxacin combined with a mucolytic agent for cystic fibrosis patients. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2017;43:1378–89.

Zhao H, Le Y, Liu H, Hu T, Shen Z, Yun J, et al. Preparation of microsized spherical aggregates of ultrafine ciprofloxacin particles for dry powder inhalation (DPI). Powder Technol. 2009;194:81–6.

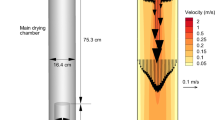

Cotabarren I, Bertín D, Razuc M, Ramírez-Rigo M, Piña J. Modelling of the spray drying process for particle design. Chem Eng Res Des. 2018;132:1091–104.

Adi H, Young P, Chan H, Salama R, Traini D. Controlled release antibiotics for dry powder lung delivery. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2010;36:119–26.

Lee SH, Teo J, Heng D, Zhao Y, Kiong W, Ng H, et al. A novel inhaled multi-pronged attack against respiratory bacteria. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2015;70:37–44.

ACS-GCIPR. American Chemical Society, Green Chemistry Institute, Pharmaceutical Roundtable. https://www.acs.org/content/acs/en/greenchemistry/industry-business/pharmaceutical.html. (Accessed 19 Sept 2017).

Paluch K, McCabe T, Müller-Bunz H, Corrigan O, Healy A, Tajber L. Formation and physicochemical properties of crystalline and amorphous salts with different stoichiometries formed between ciprofloxacin and succinic acid. Mol Pharm. 2013;10:3640–54.

Gallo L, Llabot J, Allemandi D, Bucalá V, Piña J. Influence of spray-drying operating conditions on Rhamnus purshiana (Cáscara sagrada) extract powder physical properties. Powder Technol. 2011;208:205–14.

Anderson M, Whitcomb P. DOE Simplified. Practical tool for effective experimentation. 3rd ed. New York: CRC Press; 2007.

Ceschan N, Bucalá V, Ramírez-Rigo M. New alginic acid-atenolol microparticles for inhalatory drug targeting. Mater Sci Eng. 2014;41:255–66.

USP. United States Pharmacopeia. United States Pharmacopeia and National Formulary. Rockville. MD. 2007. (USP 30-NF 25).

Ceschan N. Development of particles for inhalation administration based on polyelectrolyte-drug systems (Doctoral dissertation). 2017. http://repositoriodigital.uns.edu.ar/handle/123456789/3437 (Accessed 19 Sept 2017).

Wang H, John W. Particle density correction for the aerodynamic particle sizer. Aerosol Sci Technol. 1987;6:191–8.

Copley Scientific Ltd. Quality solutions for inhaler testing. Nottingham, UK 2015. http://www.copleyscientific.com/files/ww/brochures/Inhaler%20Testing%20Brochure%202015_Rev4_Low%20Res. (Accessed 19 Sept 2017).

Stass H, Nagelschmitz J, Willmann S, Delesen S, Gupta A, Baumann S. Inhalation of a dry powder ciprofloxacin formulation in healthy subjects: a phase I study. Clin Drug Investig. 2013;33:419–27.

De Soyza A, Aksamit T, Bandel T, Criollo M, Elborn J, Krahn U, et al. Late-breaking abstract: respire 1: ciprofloxacin DPI 32.5mg b.d. administered 14 day on/off or 28 day on/off vs placebo for 48 weeks in subjects with non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis (NCFB). Eur Respir J. 2016;48:272.

Marple V, Olson B, Santhanakrishnan K, Mitchell J, Murray S, Hudson-Curtis B. Next generation pharmaceutical impactor part II: archival calibration. J Aerosol Med. 2003;16:301–24.

Gallo L, Bucalá V, Ramírez-Rigo M. Formulation and characterization of polysaccharide microparticles for pulmonary delivery of sodium cromoglycate. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2017;18:1634–45.

Stahl K, Claesson M, Lilliehorn P, Linden H, Backstrom K. The effect of process variables on the degradation and physical properties of spray dried insulin intended for inhalation. Int J Pharm. 2002;233:227–37.

Liu Y, Wang J, Yin Q. The crystal habit of ciprofloxacin hydrochloride monohydrate crystal. J Cryst Growth. 2005;276:237–42.

Turel I, Bukovec P. Comparison of the thermal stability of ciprofloxacin and its compounds. Thermochim Acta. 1996;287:311–8.

Behboudi-Jobbehdar S, Soukoulis C, Yonekura L, Fisk I. Optimization of spray-drying process conditions for the production of maximally viable microencapsulated L. acidophilus NCIMB 701748. Dry Technol. 2013;31:1274–83.

Elversson J, Millqvist-Fureby A, Alderborn G, Elofsson U. Droplet and particle size relationship and shell thickness of inhalable lactose particles during spray drying. J Pharm Sci. 2003;92:900–10.

Tontul I, Topuz A. Spray-drying of fruit and vegetable juices: effect of drying conditions on the product yield and physical properties. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2017;63:91–102.

Nimmo J. Porosity and pore size distribution. In: Hillel D, editor. Encyclopedia of soils in the environment. London: Elsevier; 2003. p. 295–303.

Giovagnoli S, Palazzo F, Di Michele A, Schoubben A, Blasi P, Ricci M. The influence of feedstock and process variables on the encapsulation of drug suspensions by spray-drying in fast drying regime: the case of novel antitubercular drug–palladium complex containing polymeric microparticles. J Pharm Sci. 2014;103:1255–68.

Candioti L, De Zan M, Cámara M, Goicoechea H. Experimental design and multiple response optimization. Using the desirability function in analytical methods development. Talanta. 2014;124:123–38.

Vehring R. Pharmaceutical particle engineering via spray drying. Pharm Res. 2008;25:999–1022.

Robinson S, Stewart Smith S. 2005. Formulation for inhalation. US 6,926,908 B2. 09-12-2005.

Vippaguntaa S, Brittainb H, Granta D. Crystalline solids. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2001;48:3–26.

Razavi Rohani S, Abnous K, Tafaghodi M. Preparation and characterization of spray-dried powders intended for pulmonary delivery of insulin with regard to the selection of excipients. Int J Pharm. 2014;465:464–78.

Anastas P, Kirchhoff M. Origins, current status, and future challenges of green chemistry. Acc Chem Res. 2002;35:686–94.

McCray S and Lyon D. Green drug delivery formulations, Chapter 23 in Green techniques for organic chemistry and medicinal chemistry, W. Zhang and B.W. Cue Jr. (ed.). John Wiley & Sons, New York. 2012.

Hoppentocht M, Hagedoorn P, Frijlink H, de Boer A. Technological and practical challenges of dry powder inhalers and formulations. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2014;75:18–31.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Lic. F. Cabrera and Dra. A. Di Battista (PLAPIQUI) for their technical assistance and Plastiape (Italy) for kindly supplying the RS01 inhaler device.

Funding

Financial support was received from CONICET (PIP 112-2011-0100336112), UNS (PGI 24/B209, PGI 24/M122), and FONCyT (PICT-2014-2421). M. Razuc received financial support from CONICET for her postdoctoral fellowship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic Supplementary Material

ESM 1

(DOCX 131 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Razuc, M., Piña, J. & Ramírez-Rigo, M.V. Optimization of Ciprofloxacin Hydrochloride Spray-Dried Microparticles for Pulmonary Delivery Using Design of Experiments. AAPS PharmSciTech 19, 3085–3096 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1208/s12249-018-1137-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1208/s12249-018-1137-6