Abstract

Background

Multidrug resistance efflux pumps and biofilm formation are mechanisms by which bacteria can evade the actions of many antimicrobials. Antibiotic resistant non-typhoidal Salmonella serovars have become wide spread causing infections that result in high morbidity and mortality globally. The aim of this study was to evaluate the efflux pump activity and biofilm forming capability of multidrug resistant non-typhoidal Salmonella (NTS) serovars isolated from food handlers and animals (cattle, chicken and sheep) in Lagos.

Methods

Forty eight NTS serovars were subjected to antibiotic susceptibility testing by the disc diffusion method and phenotypic characterization of biofilm formation was done by tissue culture plate method. Phenotypic evaluation of efflux pump activity was done by the ethidium bromide cartwheel method and genes encoding biofilm formation and efflux pump activity were determined by PCR.

Results

All 48 Salmonella isolates displayed resistance to one or more classes of test antibiotics with 100% resistance to amoxicillin-clavulanic acid. Phenotypically, 28 (58.3%) of the isolates exhibited efflux pump activity. However, genotypically, 7 (14.6%) of the isolates harboured acrA, acrB and tolC, 8 (16.7%) harboured acrA, acrD and tolC while 33 (68.8%) possessed acrA, acrB, acrD and tolC. All (100%) the isolates phenotypically had the ability to form biofilm with 23 (47.9%), 24 (50.0%), 1 (2.1%) categorized as strong (SBF), moderate (MBF) and weak (WBF) biofilm formers respectively but csgA gene was detected in only 23 (47.9%) of them. Antibiotic resistance frequency was significant (p < 0.05) in SBF and MBF and efflux pump activity was detected in 6, 21, and 1 SBF, MBF and WBF respectively.

Conclusion

These data suggest that Salmonella serovars isolated from different food animals and humans possess active efflux pumps and biofilm forming potential which has an interplay in antibiotic resistance. There is need for prudent use of antibiotics in veterinary medicine and scrupulous hygiene practice to prevent the transmission of multidrug resistant Salmonella species within the food chain.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Salmonella are motile rod-shaped (bacilli) Gram negative bacteria of the family Enterobacteriaceae. Non-typhoidal salmonella serovars mostly cause gastroenteritis, bacteremia, and focal infection. Ingestion of contaminated animal products, such as poultry, pork, and other meats is a major route of transmission in humans. Direct contact is also a potential route of transmission in animals such as chicks, ducklings and other animals that may also transmit the bacterium to humans [1].

Antimicrobial resistance remains a global public health concern threatening the effectiveness of antibacterial therapy. Different variants of bacterial pathogens isolated globally have now become multidrug resistant. Antibacterial resistance occurs by numerous mechanisms including enzymatic inactivation, modification of drugs, drug target alteration or protection, and efflux of drugs through efflux pumps. Antibiotic resistance has been seen in both typhoidal and non-typhoidal serovars [2]. Food animals and handlers contribute largely to the spread of zoonotic multidrug resistant non-typhoidal Salmonella. Efflux generally involves transportation of a substance out of the cell. Efflux pumps play an essential role in the physiology of bacteria by mediating the entry and extrusion of essential nutrients, metabolic waste and xenobiotics. Bacterial efflux systems generally fall into five classes, the major facilitator (MF) superfamily, the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) family, the resistance-nodulation-division (RND) family, the small multidrug resistance (SMR) family and the multidrug and toxic compound extrusion (MATE) family [3]. Salmonella has at least one MDR pump from each family with the exception of the SMR family of efflux pumps, all of the identified MDR efflux systems also exist in E. coli with the exception of MdsABC (mds-multidrug transporter for Salmonella) which is unique to Salmonella [4]. The best characterised of the RND pumps in Salmonella is AcrB and its tripartite complex AcrAB-TolC which has many different substrates making this efflux pump (and other RND homologues) a key mediator of multidrug resistance in Gram negative bacteria including many Enterobacteriaceae [5]. Another recently described family of transport protein is the Proteobacterial antimicrobial compound efflux (PACE) systems that is said to be considered across many Gram-negative pathogens including, Klebsiella, Burkholderia, Salmonella, Pseudomonas and Enterobacter species. They have been shown to mediate resistance to several antimicrobials including chlorhexidine, dequalinium, acriflavine, benzalkonium and proflavine [6]. Biofilm formation contributes largely to the resistance of bacteria to different classes of antimicrobials. They can act synergistically with efflux pumps leading to elevated levels of clinical significance. Salmonella biofilms are encased in a matrix largely composed of two major components; curli and cellulose. They are involved in many functions including adhesion, cell aggregation, environmental persistence and biofilm formation [7]. This study was aimed at evaluating the antibiotic resistance profile of NTS serovars as well as their biofilm forming and efflux pump activity potentials.

Methods

Study design and bacterial strains

This descriptive study was conducted in Lagos southwestern Nigeria. Forty eight NTS serovars isolated from food animals comprising 28 isolates from chicken, 3 from cattle, 9 from sheep and 8 from apparently healthy food handlers as previously reported [8].

Antibiotic susceptibility testing

Antibiotic susceptibility testing (AST) was done according to the guidelines of the European committee on antimicrobial susceptibility testing [9] using the disc diffusion method. A loop full of a 24 h brain heart infusion broth culture of isolates were streaked on nutrient agar plate incubated for 24 h at 37 °C. One or two colonies were picked and emulsified in 5 mL of normal saline and adjusted to 0.5 McFarland standard. Using a sterile swab stick, bacterial suspensions were applied to the surface of Muller-Hinton agar (Oxoid, Basingstoke, UK) after which test antibiotic discs were applied and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. Zones of inhibition were measured and interpreted as Resistance (R), Intermidiate (I) and Sensitive (S) with break points of 22–19 for ceftazidime (30 μg), 19–19 for cefuroxime (30 μg), 17–14 for gentamicin (10 μg), 17–17 for cefixime (5 μg), 24–22 for ofloxacin (5 μg), 19–19 for amoxilin + clavulanic acid (30 μg), 11–11 for nitrofurantion (300 μg), 25–22 for ciprofloxacin (5 μg), 15–11 for tetracycline (30 μg), 19–15 for nalidixic acid (30 μg) and 22–17 for Imipenem (30 μg) (range implies the values between sensitivity ≤ and resistance >). AST was done in duplicates and Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 was used as quality control organism.

Phenotypic characterization of biofilm formation

Tissue culture plate method

Biofilm formation was evaluated by the tissue plate method according to Christensen et al. [10] and Cavant et al. [11] with slight modifications. Isolates were inoculated into brain heart infusion broth (Oxoid, Basingstoke, UK) supplemented with 2% of sucrose and incubated for 18 h at 37 °C. A one in 100 dilution of the culture was made with fresh sterile brain heart infusion broth and 0.2 mL was dispensed into individual wells of a 96 well tissue culture plate. Sterile broth served as negative control and Salmonella Typhimurium 14028 was inoculated into separate wells as positive control. Incubation was done at 37 °C for 24 h. After incubation content of each well was gently removed by tapping the plates. The wells were washed four times with 0.2 mL of phosphate buffer saline (PBS pH 7.2) to remove free-floating planktonic bacteria. The plates were then stained with crystal violet (0.1% w/v) and allowed to stay for 45 min. Excess stain was rinsed off by washing with deionized water thrice and plates were allowed to air dry. Crystal violet incorporated by the adherent cells was solubilized by adding 200 μL of 33% glacial acetic acid (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). The optical density (OD) of each well was determined with an Emax® Plus Microplate Reader (Molecular Devices San Jose, CA) at wave length 570 nm. The experiment was performed in triplicates and repeated three times. Absorbance was calculated by subtracting the OD570 of control from that of the assays OD570 with mean value determined for each isolate. Data obtained was used to classify OD570 values < 0.120 as weak biofilm formers, values between 0.120–0.240 as moderate biofilm formers, and > 0.240 as strong biofilm formers.

Determination of efflux pump activity by Ethidium bromide cartwheel method

The ethidium bromide cartwheel method according to Martins et al. [12] was used in evaluating efflux pump activity in isolates. Approximately 106 cells per mL of Salmonella isolates were streaked on Muller-Hinton agar plates containing 0 mg/L, 0.5 mg/L, 1 mg/l, 1.5 mg/L and 2 mg/L concentrations of EtBr and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. After incubation, the plates were examined under UV light. Fluorescence of isolates at different concentrations of EtBr were noted. Isolates without fluorescence indicated active efflux pump activity while those that fluoresced lacked efflux pump activity.

Detection of efflux pump and biofilm encoding genes

Genomic DNA of isolates was extracted according to the method of Kpoda et al. [13] Four efflux pump encoding genes (acrA, acrB, acrD tolC) and one biofilm formation encoding gene (csg A) were assayed for by monoplex PCR targeting specific primers listed in Table 1. A 20 μL PCR reaction was used which contained 10.8 μL nuclease free water, 0.6 μL forward primer, 0.6 μL reverse primer, 4 μL DNA template and 4 μl of 5X PCR Master Mix (7.5 mM MgCl2, 1 Mm dNTPs, 0.4 M Tris-HCl, 0.1 M (NH4)2SO4, 0.1% Tween-20, FIREPol DNA Polymerase) (Solis BioDyne Estonia). PCR was carried out in an Eppendorf thermal cycler (Eppendorf AG, Hamburg, Germany) with PCR programming conditions of initial DNA denaturation at 95 °C for 5 min, followed by 30 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing at 57 °C for csgA, 56 °C for acrA, 54 °C for tolC and 55 °C for acrB and 51 °C for acrD for 30 s and extension at 72 °C for 2 min, followed by a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. PCR products were electrophoresed at 100 V for 1 h in 2% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide and visualized under ultraviolet trans-illuminator (Cleaver Scientific Ltd). A 100 bp DNA ladder (Solis Biodyne, Estonia) was used as a molecular weight marker.

Data analysis

Graphics and data analysis were performed by Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Cooperation, 2013 USA) and GraphPad Prism version 8.0.2 (GraphPad Software Inc. USA). One way ANOVA test was used to determined association between variables. Statistical significance was considered for p < 0.05.

Results

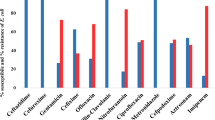

All 48 (100%) Salmonella isolates were susceptible to nitrofurantion and imipenem. They all (100%) were however, resistant to amoxicillin-clavulanic acid. Forty five (93.8%) of the isolates were resistant to ceftazidime and cefuroxime, 13 (27.1%) were resistant to cefixime, 23 (47.9%) were resistant to gentamicin, 15 (31.3%) were resistant to ofloxacin, 19 (39.6%) were resistant to ciprofloxacin, 33 (68.8%) were resistant to tetracycline and 20 (41.7%) were resistant to nalidixic acid as shown in Table 2. Twenty five (52.1%) of the isolates were multidrug resistant (MDR).

All Salmonella isolates were biofilm formers and 23 (47.9%), 24 (50.0%) and 1 (2.1%) of the isolates were strong (SBF), moderate (MBF) and weak (WBF) biofilm formers respectively. Also 28 (58.3%) of the isolates phenotypically displayed efflux pump activity as they did not fluoresce under UV light since they did not retain ethidium bromide within their cells as shown in Fig. 1. Of the 25 MDR isolates 7 were SBF and 18 were MBF while the WBF was not MDR. Furthermore, efflux pump activity was detected in 6, 21, and 1 SBF, MBF and WBF respectively as shown in Fig. 2. It was also observed that antibiotic resistance frequency was significant (p < 0.05) in SBF and MBF as shown in Fig. 3. Although all the isolates had the ability to form biofilm, csgA gene was only detected in 23 (47.9%) of the isolates as shown in Fig. 4.

acrA, acrB and tolC were detected in 7 (14.6%) of the isolates, acrA, acrD and tolC were detected in 8 (16.7%) of the isolates while 33 (68.8%) possessed all four genes acrA, acrB, acrD and tolC. Although majority of isolates from chicken, sheep and human harboured all four efflux pump genes, some did not phenotypically exhibit efflux pump activity as shown in Table 3.

Discussion

In this study all Salmonella isolates were sensitive to imipenem and nitrofurantoin indicating a low pressure on the use of these antibiotics. This is in line with the study of Akinyemi et al. [17] who reported a 100% sensitivity of Salmonella spp. isolated from different sources in Nigeria to imipenem. Similarly, Albert et al. [18] in their findings reported a total sensitivity of NTS isolated from blood stream infection in Kuwait to imipenem. However, antibiotic resistance to various classes of antibiotics was recorded in this study with 52.1% of MDR isolates. Salmonella serovars showed high resistance to third generation cephalosporins where 93.8% were resistant to ceftazidime and cefuroxime and 27.1% were resistant to cefixime. This is in line with the report of Musa et al. [19] who reported multiple resistance patterns of Salmonella species isolated from human stool samples and raw meat to cefuroxime, ceftazidime and ceftriaxone in Niger state Nigeria. In a previous study, Akinyemi et al. [20] in Lagos Nigeria also reported increase in Salmonella spp. resistance to third generation cephalosporin. Resistance of NTS serovars to quinolones in this study was also common. Twenty (41.7%), 15 (31.3%) and 19 (39.6%) Salmonella serovars were resistant to nalidixic acid, ofloxacin and ciprofloxacin respectively. Quinolones most especially ciprofloxacin remains a drug of choice for the treatment of Salmonella. However the wide spread resistance to this antibiotic is worrisome. Katiyo et al. [21] in a study between 2004 and 2015 of NTS bacteremia in England revealed a high resistance to ciprofloxacin and nalidixic acid. All Salmonella isolates in this study had biofilm forming capability which comprised 23 (47.9%) of SBF, 24 (50%) of MBF and 1 (2.1%) of WBF. Of these biofilm formers 7 of the SBF and 18 of the MBF were MDR indicating the probable role of biofilm in mediating multidrug resistance as the only WBF was not MDR. In a similar study, Farahani et al. [22] reported a 34.5% prevalence of strong biofilm forming MDR S. Enteritidis isolated from poultry and clinical isolates. Furthermore, csgA gene was detected in 23 (47.9%) of Salmonella isolates in this study. csgA gene is known to facilitate biofilm formation in Salmonella species as it is part of the csgBAC operon that encodes the structural genes of curli fimbriae [23]. Efflux pumps are important mechanisms that mediate antibiotic resistance in Salmonella. The resistance-nodulation-division (RND) family of efflux pump to which the acrAB-tolC and acrD belong has been widely reported in E. coli and Salmonella spp. and is known to confer MDR [24]. In this study a combination of all four gene acrA, acrB, acrD and tolC were detected in 33 (68.8%) of the Salmonella isolates, while acrA, acrB and tolC were present in 7 (14.6%) and 8 (16.7%) harboured acrA, acrD and tolC. Of these isolates that possessed these genes, 28 (58.3%) comprising 6 SBF, 21 MBF and 1 WBF phenotypically exhibited efflux pump activity. The presence of these genes could be linked to the observed resistance profile of the isolates. In the report of Yamasaki et al. [25] it was detected that the overexpression of acrD resulted in increased drug resistance in S. Typhimurium. Similarly, Shen et al. [26] reported the involvement of AcrAB-TolC efflux pump system in mediating fluoroquinolone resistance in Salmonella serovars isolated from meat and human in China. The role of these efflux pumps transcends mediating antibiotic resistance, their role in biofilm formation and other physiological functions have been reported. Buckner et al. [27] reported the role of acrD efflux pump in the biology of Salmonella including virulence, basic metabolism and stress responses. Baugh et al. [28] also demonstrated a link between biofilm formation and efflux pump systems of Salmonella. Hence, the presence of these efflux pumps in Salmonella isolates as observed in this study bring to bear intrinsic mechanism explored by this pathogen in extruding extraneous materials including antibiotics and in maintaining viability.

Conclusion

In this study several Salmonella serovars isolated from food animals and food handlers were multidrug resistant which would have been mediated by efflux pump activity and biofilm formation potentials which they possessed. Beyond mediating antibiotic resistance, biofilm formation by Salmonella spp. also enable them to be persistent in food processing environments hence promoting their transmission and colonization of multiple hosts. Therefore, food, personal and environmental hygiene is imperative with constant epidemiological surveillance to track and control the transmission of the pathogen within the food chain.

Availability of data and materials

Data sets used and analysed for this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. All data generated or analysed during this study are also included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- EtBr:

-

Ethidium bromide

- MDR:

-

Multidrug resistant

- MBF:

-

Moderate biofilm former

- NTS:

-

Non-typhoidal Salmonella

- RND:

-

Resistance nodulation division

- SBF:

-

Strong biofilm former

- OD:

-

Optical density

- WBF:

-

Weak biofilm former

References

Vora K, Kang SY, Shukla S, Mazur E. Fabrication of disconnected three-dimentional silver nanostructures in a polymer matrix. Appl Phys Lett. 2012;100(6):063120.

Harish BN, Menezes GA. Antimicrobial resistance in typhoidal salmonellae. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2011;29(3):223–39.

Poole K. Efflux-mediated antimicrobial resistance. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2005;56(1):20–51.

Nishino K, Latifi T, Groisman EA. Virulence and drug resistance roles of multidrug efflux systems of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Mol Microbiol. 2006;59:126–41.

Paulsen IT, Brown MH, Skurray RA. Proton-dependent multidrug efflux systems. Microbiol Rev. 1996;60(4):575–608.

Hassan KA, Liu Q, Elbourne LDH, Ahmad I, Sharples D, Naidu V, et al. Pacing across the membrane: the novel PACE family of efflux pumps is widespread in gram-negative pathogens. Res Microbiol. 2018;169:450–4.

Jonas K, Tomenius H, Kader A, Normark S, Römling U, Belova LM, et al. Roles of curli, cellulose and BapA in Salmonella biofilm morphology studied by atomic force microscopy. BMC Microbiol. 2007;7(1):70–80.

Ajayi A, Smith SI, Bode-Sojobi IO, Kalpy JC, Jolaiya TF, Adeleye AI. Virulence profile and serotype distribution of salmonella enterica serovars isolated from food animals and humans in Lagos Nigeria. Microbiol Biotechnol Lett. 2019;47(2):1–7.

The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Break point tables for interpretation of MICs and zone diameters version 9.0; 2019. http://www.eucast.org. Accessed 10 July 2019

Christensen GD, Simpson WA, Bisno AL, Beachey EH. Adherence of slime–producing strains of Staphylococcus epidermidis to smooth surfaces. Infect Immun. 1987;37:318–26.

Chavant P, Gaillard-Martinie B, Talon R, Hebraud M, Bernardi T. A new device for rapid evaluation of biofilm formation potential by bacteria. J Microbiol Methods. 2007;68:605–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mimet.2006.11.010.

Martins M, McCusker MP, Viveiros M, Couto I, Fanning S, Pages JM, et al. A simple method for assessment of MDR bacteria for over-expressed efflux pumps. Open Microbiol J. 2013;7:72–82.

Kpoda DS, Ajayi A, Somda M, Traore O, Guessennd N, Ouattara AS, et al. Distribution of resistance genes encoding ESBLs in Enterobacteriaceae isolated from biological samples in health centers in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. BMC Res Notes. 2018;11:471.

Chakrabarty RP, Sultana M, Shehreen S, Akter S, Hossain MA. Contribution of target alteration, protection and efflux pump in achieving high ciprofloxacin resistance in Enterobacteriaceae. AMB Express. 2016;6:126–38.

Baugh S. Role of multidrug efflux pumps in biofilm formation of Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium. University of Birmingham; 2013. p. 48–53.

Schiebel J, Bohm A, Nitschke J, Burdukiewicz M, Weinreich J, Ali A, et al. Genotypic and phenotypic characteristics associated with biofilm formation by human clinical Escherichia coli isolates of different Pathotypes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2017;83(24):e01660–77.

Akinyemi KO, Ajoseh SO, Iwalokun BA, Oyefolu AOB, Fakorede CO, Abegunrin RO, et al. Antimicrobial resistance and plasmid profiles of Salmonella enterica serovars from different sources in Lagos Nigeria. Health. 2018;10:758–72.

Albert MJ, Bulach D, Alfouzan W, Izumiya H, Carter G, Alobaid K, et al. Non-typhoidal Salmonella blood stream infection in Kuwait clinical and microbiological characteristics. PLoS Neg Trop Dis. 2019;13(4):e0007293.

Musa DA, Aremu KH, Ajayi A, Smith SI. Simplex PCR assay for detection of blaTEM and gyrA genes, antimicrobial susceptibility pattern and plasmid profile of salmonella spp. isolated from stool and raw meat samples in Niger state, Nigeria. Microbiol Biotechnol Lett. 2020;48(2):1–6.

Akinyemi KO, Iwalokun BA, Oyefolu AOB, Fakorede CO. Occurrence of extended spectrum and AmpC β-lactamases in multiple drug resistant Salmonella isolates from clinical samples in Lagos Nigeria. Infect Drug Resist. 2017;10:19–25.

Katiyo S, Muller-Pebody B, Minaji M, Powell D, Johnson AP. Pinna De, et al. epidemiology and outcomes of non-typhoidal Salmonella bacteremias from England, 2004-2015. J Clin Microbiol. 2019;57:e01189–18.

Farahani RK, Ehsani P, Ebrahimi-Rad M, Khaledi A. Molecular detection of virulence genes, biofilm formation and antibiotic resistance of Salmonella enterica serotype Enteritidis isolated from poultry and clinical samples. Jundishapur J Microbiol. 2018;11(10):e69504.

Hag ME, Feng Z, Su Y, Wang X, Yassin A, Chen S, et al. Contribution of the csgA and bcsA genes to Salmonella enterica serovar Pullorum biofilm formation and virulence. Avian Pathol. 2017;46:541–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/03079457.2017.1324198.

Michelle BMC, Blair JMA, La Ragione RM, Newcombe J, Dwyer DJ, Ivens A, et al. Beyond antimicrobial resistance: evidence for a distinct role of the AcrD efflux pump in Salmonella biology. MBio. 2016;11:1–10.

Yamasaki S, Nagasawa S, Hayashi-Nishino M, Yamaguchi A, Nishino K. AcrA dependency of the AcrD efflux pump in salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. J Antibiot. 2011;64:433–7.

Shen J, Yang B, Gu Q, Zhang G, Yang J, Xue F, et al. The role of AcrAB-TolC efflux pump in mediating fluoroquinolone resistance in naturally occurring salmonella isolates from China. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2017;14:12.

Buckner MMC, Blair JMA, La Ragione RM, Newcombe J, Dwyer DJ, Ivens A, et al. Beyond antimicrobial resistance: evidence for a distinct role of the AcrD efflux pump in Salmonella biology. mBio. 2016;7(6):e01916. https://doi.org/10.1128/mBio.01916-16.

Baugh S, Ekanayaka AS, Piddock LJV, Webber MA. Loss of or inhibition of all multidrug resistance efflux pumps of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium results in impaired ability to form a biofilm. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67:2409–17.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Funding

This study did not receive any funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Olubisose ET and Ajayi contributed to data collection and preparation of draft, Smith SI and Adeleye AI contributed to conceptualization of study, supervision and correction of draft. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Human Research and Ethical Committee (HREC), Lagos University Teaching Hospital with code number ADM/DCST/HREC/APP/1118 and Nigerian Institute of Medical Research – Institutional Review Board, with project number IRB/12/180.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

There is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Olubisose, E.T., Ajayi, A., Adeleye, A.I. et al. Molecular and phenotypic characterization of efflux pump and biofilm in multi-drug resistant non-typhoidal Salmonella Serovars isolated from food animals and handlers in Lagos Nigeria. One Health Outlook 3, 2 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s42522-021-00035-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s42522-021-00035-w