Abstract

Background

Systemic embolism is a common complication of infective endocarditis, most frequently involving the central nervous system, spleen, kidney, liver, and iliac or mesenteric arteries, but embolisation to coronary artery causing sudden cardiac death is infrequently encountered.

Case presentation

A case of a 45-year-old male who had a coiling procedure for anterior communicating artery aneurysm 6 weeks prior to his death. He was asymptomatic until a week prior to his death. The decedent had a fever and was treated for urinary tract infection with oral cefuroxime. He had a sudden onset of breathlessness and died at his home. Post mortem examination revealed a dilated aortic valve with vegetation. Part of the vegetation dislodged in the left coronary ostium and caused luminal occlusion. The left kidney showed scarred surface and poorly demarcated corticomedullary junction. However, the right kidney and urinary bladder were unremarkable. Microscopic examination revealed the septic thrombus both on the valve and in the left coronary ostium extended to the left main stem coronary artery. However, there was no evidence of myocardial ischemia. Blood culture grew Enterococcus faecalis which are usually associated with intravenous procedure and urinary tract infection. The culture from the vegetation also grew Enterococcus species. The left kidney also showed microscopic evidence of chronic pyelonephritis.

Conclusion

This case highlights the rare complication of infective endocarditis which caused sudden cardiac death.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The mortality due to infective endocarditis is still ranging from 16 to 25% with a high incidence of embolic events, ranging from 13 to 49%, despite recent improvements in diagnostic and therapeutic strategies (Thuny et al. 2005). Systemic embolism is a common complication of infective endocarditis, most frequently involving the central nervous system, spleen, kidney, liver, and iliac or mesenteric arteries, but embolisation to coronary artery causing sudden cardiac death is infrequently encountered. Furthermore, coronary artery embolism has a poor outcome, especially if complicated with myocardial infarction (Wenger and Bauer 1958). Perera et al. described a case of acute myocardial infarction due to embolism of bacterial vegetation on aortic valve in a drug abuser woman (Perera et al. 2000). We report a case of sudden cardiac death due to coronary artery embolism caused by aortic valve vegetation 6 weeks after coiling procedure for cerebral aneurysm in a previously healthy adult.

Case presentation

A 45-year-old male, morbidly obese with a body mass index of 45.2 kg/m2, was brought in dead to our Forensic Department. He had no history of drug abuse and was asymptomatic until he was admitted for subarachnoid haemorrhage due to cerebral aneurysm which was 6 weeks prior to death. He was hospitalised for 14 days and underwent a coiling procedure for anterior communicating artery aneurysm. The coiling procedure was uneventful. The patient was on the urinary catheter during the hospital stay. Post catherisation urine culture and blood culture were taken due to fever in the hospital. The cultures, however, were negative, but he was treated for urinary tract infection based on his symptoms and traces of leucocytes and nitrates in his urine. He had no history of hospital admission before the procedure. The deceased had a fever and was treated for urinary tract infection with tablet cefuroxime as outpatient 1 week prior to death. On the day of his death, he had a sudden onset of breathlessness and became unresponsive within minutes.

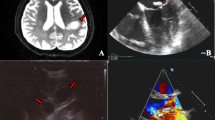

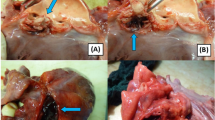

Post mortem examination showed no stigmata of infective endocarditis externally. On the internal examination, his heart weighed 410 g. The aortic valve was dilated with crumbly mobile vegetation on the left aortic cusp measured 1 cm × 1 cm × 0.8 cm (Fig. 1a). The left aortic cusp was eroded. Vegetation on other cusps was small. Part of the vegetation occluded the left ostia extended to the left main stem coronary artery, measured 1 cm in length (Fig. 1b). There was no gross evidence of infarction on the myocardium. The left kidney showed scarred surface and poorly demarcated corticomedullary junction. However, the right kidney and urinary bladder were unremarkable. In the brain, the coiling was intact and no evidence of meningeal haemorrhage. The lungs were not oedematous as well as no evidence of pleural or peritoneal effusion. Microscopic examination of the embolic material in the left main coronary artery and the vegetation showed inflammatory cells predominantly neutrophils. The inflammatory cells were mixed with fibrin. Histological examination also showed the presence of bacterial colonies consistent with septic embolic vegetation (Fig. 2). Sections of the kidney showed the presence of numerous sclerosed glomeruli with marked inflammatory infiltration predominantly lymphocytes and histiocytes. There was also evidence of interstitial fibrosis and atrophic tubules (Fig. 3). The kidney findings were consistent with chronic pyelonephritis. Blood culture grew Enterococcus faecalis while spleen culture and culture from the vegetation grew Enterococcus species.

Discussion

Native valve endocarditis is a serious and potentially life threatening. According to the multicentre prospective European study, 34.1% of patients developed embolic phenomena of which 62% had cerebral emboli and 49% had splenic emboli. Only about 1% of patients developed coronary emboli (Thuny et al. 2005). So far, only six cases of coronary embolism from infective endocarditis (IE) causing sudden cardiac death secondary to left main stem occlusion have been reported (Tiurin and Korneev 1992). The left main stem is a shorter and wider than its branches. It is most likely the emboli obstructed the branches, namely the left anterior descending artery and left circumflex artery.

Sudden cardiac death can occur in the early stages of an acute coronary occlusion either due to ventricular arrhythmias, pulseless electrical activity or asystole causing haemodynamic collapse. Most embolic events occur in the left anterior descending artery, which arises from the mitral valve vegetation and from prosthetic valve (Low and Kern 2014). The prevalence of the left coronary artery occlusion is higher than the right coronary due to its less angulated take-off and downward course (Tayama et al. 2007). Higher incidences of embolic phenomena were also reported among intravenous drug users with right-sided endocarditis and patients who had positive blood cultures. The risk of developing embolism is higher if the vegetation size is more than 10 mm, increasing mobility of vegetation, and in cases of Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus bovis infections (Tayama et al. 2007; Shamsham et al. 2000).

Blood culture, spleen culture and culture from the vegetation which grew Enterococcus species is commonly associated with intravenous procedure and urinary tract infection. The source of enterococcal endocarditis in our case could arise from either the coiling procedure or from the left pyelonephritis or both. The deceased had intravenous procedure 6 weeks prior to his death. The intravenous procedure could have introduced the Enterococcus into the bloodstream. The other source is the bloodstream infection from pyelonephritis. We believe that the deceased has recent pyelonephritis despite the left kidney shows evidence of chronic pyelonephritis in the post mortem. This is owing to the short lifespan of the polymorphs and the course of antibiotics that may have treated the renal infection very quickly. The antibiotics that succeeded in the kidney may fail in the heart because bacteria embedded within the vegetation may have been shielded from the drugs in the bloodstream. We also believe that the occlusion was rapid and resulted in his death. Therefore, there was no evidence of myocardial ischemia seen macroscopically or microscopically (McVie 1970; Dettmeyer 2018; Cummings et al. 2013). The mechanism of death attributed to cardiac arrhythmias.

Conclusion

This case highlights the rare complication of infective endocarditis, which caused sudden cardiac death. We believe that the death was caused by arrhythmias due to septic emboli occluding the coronary artery. The deceased has two significant risk factors in developing infective endocarditis, namely pyelonephritis, and coiling procedure.

Abbreviations

- IE:

-

Infective endocarditis

References

Cummings P, Springer K, Trelka D (2013) Atlas of forensic histopathology. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 98–110

Dettmeyer R (2018) Forensic histopathology. Springer International PU:246–250

Low LS, Kern KB (2014) Importance of coronary artery disease in sudden cardiac death. J Am Heart Assoc: Cardiovascular and Cerebrovascular Disease 3(5):e001339

McVie JG (1970) Postmortem detection of in apparent myocardial infarction. J Clin Pathol 23:203–209

Perera R, Noack S, Dong W (2000) Acute myocardial infarction due to septic coronary embolism. N Engl J Med 342:977–978

Shamsham F, Safi AM, Pomerenko I et al (2000) Fatal left main coronary artery embolism from aortic valve endocarditis following cardiac catheterization. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 50:74–77

Tayama E, Chihara S, Fukunaga S et al (2007) Embolic myocardial infarction and left ventricular rupture due to mitral valve endocarditis. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 13:206–208

Thuny F, Di Salvo G, Belliard O et al (2005) Risk of embolism and death in infective endocarditis: prognostic value of echocardiography: a prospective multicenter study. Circulation 112:69–75

Tiurin VP, Korneev NV (1992) The mechanisms of the development and diagnosis of myocardial infarct in septic endocarditis. Ter Arkh 64:55–58

Wenger NK, Bauer S (1958) Coronary embolism: review of the literature and presentation of fifteen cases. Am J Med 25:549–557

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Director General of Health in Malaysia for his permission to publish this article. Also, we would like to express our appreciation to the Director of Hospital Kuala Lumpur and Director of the National Institute of Forensic Medicine, Malaysia, for allowing the use of resources throughout the study.

Availability of data and materials

The data and material used for this case report is available upon request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KS is the main author and case contributor of the manuscript. SS is the co-author and case contributor of the manuscript. LPS and SSF are the co-authors and proofreaders of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

No ethical approval was required as only patient’s data were utilised without any clinical intervention.

Consent for publication

All post mortem is done as per police or court order. Hence, no consent was required prior to post mortem.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Subramaniam, K., Serangan, S., Soon, L.P. et al. Sudden cardiac death due to coronary artery embolism secondary to native aortic valve endocarditis in a young adult. Egypt J Forensic Sci 8, 55 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41935-018-0086-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41935-018-0086-2