Abstract

Background

Symptoms of acquired tracheobronchomalacia (TBM) include wheezing, shortness of breath, and chronic cough, and can negatively affect quality of life. Successful treatment of TBM requires identification of the disorder and of contributing factors. Acquired TBM is generally associated with a number of conditions, including asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and gastroesophageal reflux. Although a possible relationship with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) has been observed, data illuminating such an interaction are sparse.

Methods

In the present study, we analyzed the percent tracheal collapse (as measured on dynamic chest CT) and detailed sleep reports of 200 patients that had been seen at National Jewish Health, half of which had been diagnosed with OSA and half which did not have OSA.

Results

Tracheal collapse ranged from 0 to 99% closure in the population examined, with most subjects experiencing at least 75% collapse. OSA did not relate significantly to the presence or severity of tracheobronchomalacia in this population. Sleep disordered breathing (SDB) did show a strong association with TBM (p < 0.03).

Conclusions

Tracheobronchomalacia may develop as a result of increased negative intrathoracic pressure created during attempts at inhalation against a closed or partially closed supraglottic area in patients experiencing apneic or hypopneic events, which contributes to excessive dilation of the trachea. Over time, increased airway compliance develops, manifesting as tracheal collapse during exhalation. Examining TBM in the context of SDB may provide a reasonable point at which to begin treatment, especially as treatment of sleep apnea and SDB (surgical or continuous positive airway pressure) has been shown to improve associated TBM.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Tracheomalacia (TM) and tracheobronchomalacia (TBM) manifest clinically as wheezing, chronic cough, and shortness of breath, and can negatively affect quality of life (Choo et al. 2013). TBM and TM are characterized by the collapse of the trachea (and bronchi, in the case of TBM) during forced expiration. Untreated TM can progress to TBM over time (Nuutinen 1977), though little is known about the histopathological changes in TBM in adults (Majid 2017). The degree of severity of TBM can be described as the percentage of anterior-posterior narrowing of the tracheal or bronchial wall during forceful exhalation or as the percentage of reduction in tracheal or bronchial lumen cross-sectional surface area (Murgu and Colt 2013). There is not a consistent standard in the literature for the point at which tracheal collapse becomes clinically significant; 50 to 80% collapse has been reported as such (Murgu and Colt 2013; Carden et al. 2005). TBM is reported to occur in 4.5–23% of the population, but the true incidence is difficult to determine (Carden et al. 2005; Jokinen et al. 1977). Acquired TBM is often discussed in an overlapping fashion with TM, hyperdynamic airway collapse (HDAC) and excessive dynamic airway collapse (EDAC) (Majid 2017). TBM is diagnosed either by direct observation of the airway during bronchoscopy or by dynamic expiratory imaging with multidetector computed tomography (CT) (Carden et al. 2005). Observations in adults have commonly associated acquired TBM with asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and upper gastrointestinal disorders (aspiration, laryngopharangeal reflux [LPR], gastroesophageal reflux disease [GERD], reflux), as well as chronic cough (Murgu and Colt 2013; Carden et al. 2005; Palombini et al. 1999). In addition, obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and/or sleep disordered breathing (SDB) have been occasionally associated with TBM (Ehtisham et al. 2015; Peters et al. 2005).

Though a connection between OSA and TBM has been observed before (Ehtisham et al. 2015; Peters et al. 2005; Seaman and Musani 2012; Sundaram and Joshi 2004), there is a paucity of data elucidating a mechanism for such a relationship. We performed a medical record database search to review this relationship in more detail through analysis of sleep studies, dynamic expiratory imaging, respiratory function, and concomitant diagnoses. We hypothesized that OSA may be an important contributor to the development of TBM. Increased negative intrathoracic pressure that occurs as a result of attempting to maintain airflow during obstructive events may induce tracheal over-dilation, gradually leading to increased tracheal compliance and collapse during exhalation (Peters et al. 2005).

Methods

This study was approved by the National Jewish Health Institutional Review Board (IRB #HS2990). A target of 100 total subjects with OSA and 100 without OSA was selected. The medical records database at National Jewish Health was queried twice to find patients with orders for both a sleep study and a high resolution chest CT with dynamic expiratory imaging. The initial search for subjects with an ICD-10 code for OSA yielded 331 subjects. The second search, excluding the ICD-10 code for OSA, provided 185 subjects. From both groups, subjects were excluded from analysis for the following reasons: one or both necessary studies were ordered but not completed, chest CT and sleep studies were greater than 12 months apart, home sleep studies, and/or diagnosis of central sleep apnea in the absence of OSA. Records were reviewed until each cohort contained 100 subjects. During data analysis, one subject was moved from the non-OSA group to the OSA group due to an error in the medical record, making the final count 101 patients with OSA and 99 without OSA.

Data collected from scored sleep reports were: O2 saturation (SaO2) nadir and time below 88% saturation, Respiratory Disturbance Index (RDI), Apnea-Hypopnea Index (AHI), REM AHI, Supine AHI, Supine REM AHI, total apneas, total hypopneas, and total sleep time. Whether or not a patient was given oxygen supplementation during the study was additionally noted. Severity of OSA was determined by the AHI; OSA was considered to be mild if the AHI was between 5 and 15, moderate if the AHI was 15 to < 30, and severe if AHI was ≥30 (Bibbins-Domingo et al. 2017). The AHI is calculated from both apneas and hypopneas, averaged per hour of sleep time. In a scored sleep report, the AHI is calculated during different phases of sleep and in different sleeping positions, including but not limited to: total supine sleep, supine REM sleep, and total REM sleep (including any supine REM sleep that occurs). The RDI measures the average number of apneas, hypopneas, and respiratory event-related arousals per hour of sleep. Sleep disordered breathing (SDB) has no standard definition, but is defined here as the RDI and/or any AHI score being ≥5 per hour of sleep.

All multi-detector computed tomographic (CT) scans were performed at National Jewish Health. Sequential acquisitions at end-inspiration and during forced expiration (dynamic expiration) were made available for analysis. All CT scans were evaluated for research by a single radiologist, using TeraRecon (Aquarius, iNtuition, Version 4.4.8; TeraRecon Inc., Foster City, CA) software. Because not all subjects’ scans included B50 (lung algorithm) sequences, B35 (soft tissue algorithm) inspiratory and dynamic expiratory sequences were analyzed with lung windows (level, − 700 HU; width, 1500). On the dynamic expiratory sequences imaging, the minimum area of the trachea from the thoracic inlet through carina was identified, the tracheal perimeter was traced by hand at this level using an electronic tracing tool and its area was recorded. Next, the same anatomical cross-section of the trachea was identified on inspiratory imaging and its cross sectional area was recorded. All measurements were obtained orthogonal to the long axis of the trachea. The percentage of tracheal collapse was calculated as follows:

Patients with congenital TBM were not present in either cohort. Acquired tracheobronchomalacia and tracheomalacia were grouped together under the label of TBM to include those subjects with greater than or equal to 75% airway collapse on dynamic CT, whether or not bronchial collapse was present. Severe TBM was defined as greater than or equal to 85% collapse. The cutoff of 75% was chosen after review of the literature, in which anywhere from 50 to 80% tracheal narrowing is referenced as the defining point for TBM (Murgu and Colt 2013; Carden et al. 2005), and a mean of 54.3% tracheal collapse is reported in healthy individuals (Boiselle et al. 2009).

Spirometry data from tests closest to the date of the CT were also collected on these subjects. Forced Expiratory Volume in 1 s (FEV1), Forced Vital Capacity (FVC), FEV1/FVC, Forced Expiratory Flow at 50% of the FVC (FEF50), Forced Inspiratory Flow at 50% of the FVC (FIF50), the FEF50/FIF50 ratio, and the percent predicted of the above were analyzed.

Differences in quantitative data (i.e. spirometry, percent collapse of the trachea, and AHI) were evaluated by calculation of correlation coefficients and Student’s T-Test. Rates of various qualitative characteristics between cohorts were assessed using the Z-Test and the Z-statistic. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed in Microsoft Excel.

Results

Demographics

Two hundred patients were included in the study (Table 1). There were 70 males and 130 females (35% males, 65% females). Patients from 19 to 85 years of age were represented (mean 57.3 ± 13.83); 58% were between 51 and 70 years old. A full spectrum of BMI categories was present; 53.5% of the patients were in the obese category with a BMI of ≥30. The average BMI was 31.0 ± 6.42.

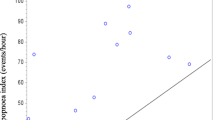

The ages of males and females were not significantly different (males 56.5 ± 15.76, females 57.7 ± 12.65). Females, as compared to males, had a higher BMI (31.8 ± 6.85 vs 29.3 ± 5.15, p = 0.009; Fig. 1), higher FEV1/FVC ratio (p < 0.001), higher FEF50/FIF50% predicted (p = 0.01), and higher FEF 50% predicted (p = 0.03). Otherwise their respiratory functions did not differ significantly. Patients with OSA were older (59.9 ± 11.59 vs 54.7 ± 15.36, p = 0.008), had higher BMI (32.3 ± 6.59 vs 29.6 ± 5.97, p = 0.003), had higher FEV1% predicted (75.92 ± 20.85 vs 67.95 ± 26.24, p = 0.019) and FEV1/FVC (73.71 ± 10.81 vs 69.33 ± 12.97, p = 0.01) than those without OSA (Table 1). Smoking histories for male versus female, subjects with and without OSA, and subjects with and without TBM were not significantly different. There were no statistically significant differences in BMI between patients with and without TBM. There were no statistically significantly different pulmonary function test results between those subjects with and without TBM. Equal proportions of males and females had TBM (24.2% of males and 26.1% of females).

Concurrent diagnoses

Diagnoses other than OSA and TBM occurring within the population here are summarized in Table 2, and are as follows: Asthma, COPD, upper GI disorders (this includes aspiration, abnormal swallow, LPR, GERD, reflux, and dysmotility), chronic/recurrent infections (pneumonia, bronchitis and recurrent pulmonary infections), VCD, and pulmonary hypertension. Pulmonary infections (OSA N = 7; non-OSA N = 1; p = 0.03), VCD (OSA N = 12; non-OSA N = 2; p = 0.006), and Pulmonary Hypertension (OSA N = 5; non-OSA N = 0; p = 0.025) occurred at significantly higher rates in patients with OSA than those without OSA. There were no statistically significant differences in the rates of comorbidities occurring between patients with and without TBM, in patients with both OSA and TBM, or in patients with Sleep Disordered Breathing (SDB) and TBM.

Sleep studies

All 200 patients had sleep studies with scored sleep reports, though not all subjects had sleep recorded in supine and/or REM sleep. Among patients with OSA, when comparing those with and without TBM, there were no significant differences in terms of oxygen saturation levels (SaO2) or the number of patients requiring supplemental O2 during sleep; however, patients with TBM spent a greater percentage of sleep time below 88% SaO2 than those without TBM (46.4% vs 21.3%, p = 0.009). This pattern holds true within the group of patients with SDB as well (39.1% time below 88% SaO2 with TBM vs 12.4% time below 88% SaO2 without TBM p = 0.003). Forty-six (46.5%) of 99 patients in the cohort without OSA (overall AHI scores < 5) had at least one elevated AHI score on their sleep report (supine AHI, REM AHI, or supine REM AHI); 26 of those had multiple elevated AHI scores. Nine patients in this group had elevated RDI scores in the absence of elevated AHI scores. Overall, 156 patients had sleep disordered breathing (as defined by RDI and/or any individual AHI value of ≥5). Only 44 subjects had completely normal sleep studies.

Though the group of patients with OSA had roughly equal proportions of males and females, 64% of males in the entire cohort had OSA, which is significantly more than did not have OSA (36%; p = 0.004). Conversely, only 43% of females had OSA while 57% did not (p = 0.004).

Tracheal collapse

Tracheal collapse in this patient population ranged from 0 to 99.5%; 74.5% of subjects demonstrated less than 75% collapse. Thirty-one percent of obese (BMI ≥30) patients had TBM, and 18% of non-obese (BMI < 30) patients had TBM; these proportions are not statistically significantly different. Percent tracheal collapse did not correlate with BMI.

Severe TBM (≥85% collapse) was present at a significantly higher rate in subjects with OSA than without OSA (15 subjects vs 6, respectively, p = 0.04). Tracheal collapse correlated significantly with supine AHI (r = 0.27, p < 0.001) in all 200 subjects, as well as in the 101 subjects with OSA (r = 0.311, p = 0.0015). All 21 of the patients with severe TBM (> 85% collapse) had SDB. In subjects with SDB, supine AHI was significantly higher in subjects with TBM than those without TBM (33.9 ± 33.7 vs 20.0 ± 28.2; p = 0.015). Supine AHI was also significantly higher in those with TBM than those without TBM, as assessed by Student’s T-Test (29.6 ± 33.3 vs 14.9 ± 25.9; p = 0.015; p = 0.003). Subjects with an elevated supine AHI had significantly higher collapse than those without an elevated supine AHI (60.0% ± 24.5 vs 52.0% ± 25.0; p = 0.03). Additionally, subjects with severely elevated supine AHI had far higher rates of collapse than those without an elevated supine AHI (51.8% ± 25.1 vs 69.2% ± 20.9; p = 0.0004).

Gender distribution in patients with both OSA and TBM was equal, but gender distribution in patients with SDB and TBM was not. This group of 44 subjects with both SDB and TBM was comprised of 61.4% females and 38.6% males (p = 0.03). One hundred percent of male patients with TBM had SDB; a significant proportion, when compared to the 79.4% of females with TBM who had SDB (p = 0.04).

SDB was associated with a higher rate of TBM; 28.2% of those in whom any AHI score, or RDI, was elevated (≥5) had TBM versus 20.0% of those with completely normal sleep studies had TBM. All 21 of the patients with severe TBM had SDB, while none of those with severe TBM had normal sleep studies; this is statistically significant (p = 0.01). In subjects with SDB, supine AHI was significantly higher in subjects with TBM than those without TBM (33.9 ± 33.7 vs 20.0 ± 28.2; p = 0.015). Overall, supine AHI was significantly higher in those with TBM than those without TBM (p = 0.003).

Discussion

Tracheal collapse is highly variable from one individual to another, even among healthy members of the population (Boiselle et al. 2009). When also accounting for the imprecise ways in which tracheal collapse is often measured, it’s not surprising that it is difficult to define the point at which the collapse becomes significant. The lack of consistency in the literature regarding clinical significance lends credence to this theory; some sources report that 50% collapse is indicative of disease, while others suggest that it is well within the range of normal and that clinically significant TBM isn’t present unless there is at least 70 or even 80% collapse (Murgu and Colt 2013; Carden et al. 2005; Boiselle et al. 2009). TBM does not exist in isolation; looking at tracheal collapse alone, and trying to decide an exact percent at which is becomes significant before trying to decide on treatment, may be irrelevant. It could, instead, be more helpful to look at patients with elevated supine AHI on their scored sleep reports. Should those individuals display moderate to severe (60% or higher) tracheal collapse alongside chronic cough and other symptoms of TBM, they should be considered for CPAP, even if their overall AHI score is normal (Seaman and Musani 2012; Sundaram and Joshi 2004; Ferguson and Benoist 1993).

Acquired TBM is most commonly seen in the middle aged and elderly (Nuutinen 1982), an observation which is borne out in the present cohort. Observations in adults have associated TBM with obesity, asthma, COPD and Upper GI Disorders (aspiration, LPR, GERD, reflux), as well as chronic cough (Murgu and Colt 2013; Carden et al. 2005; Palombini et al. 1999; Seaman and Musani 2012). It has been suggested that chronic/recurrent infections (pneumonia, bronchitis and recurrent pulmonary infections), and chronic inflammation are important contributors to the development of TBM (Feist et al. 1975); specific markers of such inflammation have not been examined (Carden et al. 2005). Acquired TBM clearly has multiple causes, but based on the observations in the group with SDB, it’s possible that more than half of cases have SDB as a major contributing factor. There has not been a general appreciation of the high incidence of TBM in patients with OSA or SDB (Ehtisham et al. 2015), yet 30% of the patients in the present study with SDB also had TBM.

Throughout the analysis of the data gathered for this study, multiple theorized causes of TBM fell short. In this population, smoking, COPD, asthma, pulmonary infections and cough held no particular connection to TBM or tracheal collapse in general. BMI, pulmonary hypertension and infections did have a relationship with OSA, but not with TBM. Surprisingly, within the cohort examined here, severity of acquired TBM did not correlate with BMI, or with any particular BMI category. More than 50% of the patients in the present cohort were obese, and 52% of the obese subjects demonstrated moderate to severe tracheal collapse. Though the tracheal collapse observed in patients with BMI ≥30 was higher than that observed in patients with a BMI < 25, the average was still below 75% collapse (60.2% vs 49.5%, p = 0.03). This is supportive of the idea discussed by Seaman and Musani (Seaman and Musani 2012), who describe obesity as a contributor to TBM and suggest that weight loss would be an effective treatment in cases of TBM. Weight loss in obese patients improves OSA and SDB (Mitchell et al. 2014), which could then reduce the amount of tracheal collapse in those patients, thereby improving associated TBM.

In our exploration of the relationship between OSA and TBM, we found that TBM (≥75% tracheal collapse) corresponds more to abnormalities in other measures of sleep-disordered breathing than to the overall AHI score and diagnosis of OSA. Eighty-six percent of patients with TBM had sleep disordered breathing evident on the scored report – though not necessarily an abnormal overall AHI. However, the overall AHI does not always represent the extent of sleep disordered breathing present. The component AHI values (supine, REM, and Supine REM), as well as the RDI, should not be overlooked. These measures represent the most severely disordered aspects of sleep, but their significance may be diminished when averaged over an entire night of sleep (Punjabi 2016). In particular, supine AHI appears to be the best predictor of tracheal collapse within this dataset. Tracheal collapse correlated significantly with supine AHI, and subjects with an elevated supine AHI had significantly greater tracheal collapse than those without an elevated supine AHI.

There are a number of limitations within this study. Because it was retrospective in nature, we were bound by the available records rather than a controlled patient selection. The relatively small cohort size of 200 patients total may preclude our finding significant differences among the subgroups. Data interpretation is limited to the impact of OSA/SDB on tracheal collapse, given that the study design was based around presence or absence of OSA rather than presence or absence of TBM.

Conclusion

In cases of moderate to severe tracheal collapse with no evident cause, it may be worthwhile to pursue a formal sleep study (Sundaram and Joshi 2004). The single subject in the present cohort with a history of tracheoplasty experienced total recurrence of TBM with a tracheal collapse of 80.9% within a year of surgery. Though this person was included in the non-OSA group due to an overall AHI of 4.1, all of the scores for AHI in supine and/or REM sleep were elevated (mean 18.8 ± 1.35). Because the patient had not had sleep testing done prior to the tracheoplasty, sleep disordered breathing was not identified. There was no sleep apnea treatment (i.e. CPAP) given, which may in part explain the relapse, as CPAP has been successfully used to treat TBM (Seaman and Musani 2012; Sundaram and Joshi 2004; Ferguson and Benoist 1993).

Though our original hypothesis was that OSA is an important contributor to the development of TBM, the data collected do not support a strong relationship between OSA and TBM. There are, however, evident connections between SDB and TBM, which support a modified hypothesis. Sleep disordered breathing, particularly in supine sleep, generates increased negative intrathoracic pressure during attempts at inhalation against a closed or partially closed supraglottic area, which contributes to excessive dilation of the trachea and proximal bronchi (Peters et al. 2005). Over time, increased airway compliance develops; this manifests as atrophy of and quantitative reduction in longitudinal elastic fibers, an increase in membranous tracheal diameter, and fragmentation of cartilaginous rings noted on histopathology and at autopsy in patients with TBM (Murgu and Colt 2013; Jokinen et al. 1977). In addition, because TBM can be successfully treated with CPAP (Sundaram and Joshi 2004; Ferguson and Benoist 1993), treating cases in which TBM occurs alongside borderline OSA, or instances where there is an elevated supine AHI, may be beneficial. Treatment of OSA either by surgical methods or CPAP has been shown to improve associated TBM (Peters et al. 2005; Sundaram and Joshi 2004).

Future studies should follow treatment of OSA with study of inflammatory markers and assessment of tracheal collapse as it coexists with OSA. Additional imaging studies, where the trachea can be visually monitored during apneic events, would shed light on this relationship more directly, though there are difficulties inherent in imaging a sleeping person. Many specific markers of inflammation have been found in OSA (Sundar and Daly 2011); however, though TBM is reported to occur with inflammation (Feist et al. 1975), specific markers have not been described. The link between upper airway inflammation and uncontrolled laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR) (Lommatzsch et al. 2013) would be another possible avenue of research. There has not been discussion of LPR and a direct relationship with OSA (i.e. treating LPR and seeing an improvement in OSA), but it may be worth examining, given the recurring connection in the literature of OSA and upper gastrointestinal disorders.

Abbreviations

- AHI:

-

Apnea-hypopnea index

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- COPD:

-

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- CPAP:

-

Continuous positive airway pressure

- CT:

-

Computerized tomography

- EDAC:

-

Excessive dynamic airway collapse

- FEF50:

-

Forced expiratory flow at 50% of the FVC

- FEV1:

-

Forced expiratory volume in 1 s

- FIF50:

-

Forced inspiratory flow at 50% of the FVC

- FVC:

-

Forced vital capacity

- GERD:

-

Gastroesophageal reflux

- HDAC:

-

Hyperdynamic airway collapse

- ICD-10:

-

International Classification of Disease, Tenth Edition

- IRB:

-

Institutional Review Board

- LPR:

-

Laryngopharyngeal reflux

- OSA:

-

Obstructive sleep apnea

- RDI:

-

Respiratory disturbance index

- REM:

-

Rapid eye movement

- SDB:

-

Sleep disordered breathing

- TBM:

-

Tracheobronchomalacia

- TM:

-

Tracheomalacia

References

Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, Curry SJ, Davidson KW, Epling JW, García FAR, et al. Screening for obstructive sleep apnea in adults. JAMA. 2017;317:407. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.20325.

Boiselle PM, O’Donnell CR, Bankier A, Ernst A, Millet ME, Potemkin A, et al. Tracheal collapsibility in healthy volunteers during forced expiration: assessment with multidetector CT. Radiology. 2009;252:255–62.

Carden KA, Boiselle PM, Waltz DA, Ernst A. Tracheomalacia and tracheobronchomalacia in children and adults: an in-depth review. Chest. 2005;127:984–1005.

Choo EM, Seaman JC, Musani AI. Tracheomalacia/tracheobronchomalacia and hyperdynamic airway collapse. Immunol Allergy Clin N Am. 2013;33:23–34.

Ehtisham M, Azhar Munir R, Klopper E, Hammond K, Musani AI. Correlation between tracheobronchomalacia/hyper dynamic airway collapse and obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191:A5037–7.

Feist JH, Johnson TH, Wilson RJ. Acquired tracheomalacia: etiology and differential diagnosis. Chest. 1975;68:340–5. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.68.3.340.

Ferguson GT, Benoist J. Nasal continuous positive airway pressure in the treatment of tracheobronchomalacia. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993;147:457–61.

Jokinen K, Palva T, Sutinen S, Nuutinen J. Acquired tracheobronchomalacia. Ann Clin Res. 1977;9:52–7.

Lommatzsch SE, Martin RJ, Good JT Jr. Importance of fiberoptic bronchoscopy in identifying asthma phenotypes to direct personalized therapy. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2013;19:42–8.

Majid A. Tracheomalacia and tracheobronchomalacia in adults. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/tracheomalacia-and-tracheobronchomalacia-in-adults. Accessed 1 Jan 2017.

Mitchell LJ, Davidson ZE, Bonham M, O’Driscoll DM, Hamilton GS, Truby H. Weight loss from lifestyle interventions and severity of sleep apnoea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med. 2014;15:1173–83.

Murgu S, Colt H. Tracheobronchomalacia and excessive dynamic airway collapse. Clin Chest Med. 2013;34:527–55.

Nuutinen J. Acquired tracheobronchomalacia: a bronchological follow-up study. Ann Clin Res. 1977;9:359–64.

Nuutinen J. Acquired tracheobronchomalacia. Eur J Respir Dis. 1982;63:380–7.

Palombini BC, Villanova CAC, Araújo E, Gastal OL, Alt DC, Stolz DP, et al. A pathogenic triad in chronic cough: asthma, postnasal drip syndrome, and gastroesophageal reflux disease. Chest. 1999;116:279–84.

Peters CA, Altose MD, Coticchia JM. Tracheomalacia secondary to obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Otolaryngol - Head Neck Med Surg. 2005;26:422–5.

Punjabi NM. COUNTERPOINT: is the apnea-hypopnea index the best way to quantify the severity of sleep-disordered breathing? No Chest. 2016;149:16–9. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.14-2261.

Seaman JC, Musani AI. Tracheobronchomalacia and hyperdynamic airway collapse. Pakistan J Chest Med. 2012;18:65–70.

Sundar KM, Daly SE. Chronic cough and OSA: a new association? J Clin Sleep Med. 2011;7:669–77.

Sundaram P, Joshi JM. Tracheobronchomegaly associated tracheomalacia: analysis by sleep study. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci. 2004;46:47–9.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to lack of IRB approval for making the dataset available, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request and IRB approval.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CK compiled and analyzed patient data, and wrote the manuscript and tables. DR initiated the project, and aided in project design, hypothesis development and manuscript preparation. TJ analyzed the patients’ dynamic CT scan images and measured the percent collapse of the trachea. AS compiled data and provided insights during the data analysis process. JG contributed to study design and manuscript feedback. JD provided manuscript support and suggestions for analysis. RM guided the project from the start, including project design, hypothesis development, and manuscript preparation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the National Jewish Health Institutional Review Board (IRB #HS2990). Consent for participation was not obtained per IRB guidelines, given the retrospective nature of the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Kolakowski, C.A., Rollins, D.R., Jennermann, T. et al. Clarifying the link between sleep disordered breathing and tracheal collapse: a retrospective analysis. Sleep Science Practice 2, 10 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41606-018-0030-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41606-018-0030-2