Abstract

Background

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) play an integral role in childhood cancer research. Several efforts to improve the quality of reporting of clinical trials have been published in recent years, including the TIDieR checklist. Many reviews have since used TIDieR to evaluate how well RCTs are being reported, but no such study has yet been done in childhood cancer. The aim of this study is to evaluate adherence of RCTs involving acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL) to the TIDieR checklist.

Methods

The PubMed database was used to screen for RCTs involving ALL published since 2015. Of 1546 articles identified, 46 met study criteria and were then evaluated against the TIDieR 12-point checklist to measure the degree of adherence.

Results

Of the 46 articles included, 9 (19.6%) met full TIDieR criteria. Seven of the 9 reported non-pharmacological interventions, and the remaining 2 reported pharmacological interventions. The average article properly reported 8.98/12 checklist items. Item 5 (intervention provider) was the most poorly reported item, properly reported in only 34.8% of articles.

Conclusion

We conclude that overall TIDieR adherence is low and needs to be adhered to more fully in order to improve research in ALL as well as in all childhood cancers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL) is the most common type of childhood cancer [1, 2]. In 2016, ALL was newly diagnosed in over 6500 cases in the U.S. and claimed 1400 lives [3]. On a global scale, the overall number of incident diagnoses of ALL is estimated to rise through 2025 [2]. In spite of increased incidence, the 5-year survival rate has steadily risen since the 1960s and recently rose above 90% for the first time [4, 5]. Research continues to yield promising discoveries concerning how ALL is managed. Specifically, randomized controlled trials have been instrumental in optimizing treatment for ALL.

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) allow scientists to test new theories that may improve clinical practice. As the gold standard for assessing new treatments, RCTs provide valuable information for clinicians who wish to implement evidence-based advancements into their practice [6, 7]. RCTs play a particularly important role in childhood cancer research, with childhood cancer patients participating in RCTs in large numbers relative to other patient populations. Therefore, it is important to maximize the efficacy of RCTs with a thorough, systematized standard.

There has been a strong push in recent years to improve reporting methods in RCTs. Due to “lack of adequate reporting” and “biased results” among reported RCTs, the first Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) report was published in 1996 to improve reporting quality [8]. Several evidence-based CONSORT reports have been published since, with the most recent revision published in 2010 [9]. Through a checklist and flowchart, CONSORT guides investigators in proper reporting of RCTs [9]. A vital piece of any clinical trial is the intervention being tested. An extension of CONSORT – the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) – was recently published to address the lack of standardization of intervention reporting [10].

The TIDieR checklist and guideline was published in 2014 to improve reporting and reproducibility of RCTs. Although many prominent medical journals endorse CONSORT [9, 11, 12] and a significant percentage of RCTs report adherence to CONSORT guidelines, “reporting of guidelines [continues to be] deficient,” partially due to “lack of awareness among authors about what comprises a good description” [10]. In response to this deficiency, an international team of experts created the TIDieR checklist with evidence-based research to increase accountability in reporting and reproducibility of interventions [10]. Since the publication of TIDieR in 2014, few studies in different fields of medicine have examined adherence of RCTs to TIDieR guidelines [13,14,15]. However, TIDieR research within the field of oncology is scarce, and no such study has been conducted on an individual childhood cancer disease. Here, we analyze adherence to the TIDieR checklist of RCTs published since 2015 involving childhood acute lymphocytic leukemia.

Methods

PubMed, which includes the MEDLINE collection, was used to search for RCTs involving childhood ALL, defined in our study as ALL occurring before 18 years of age. We chose PubMed to maximize sensitivity when searching medical journals for any aspect of treatment or diagnosis of childhood ALL [16]. To search PubMed with maximum sensitivity for RCTs pertaining to pediatric ALL, we implemented an evidence-based search strategy from The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR). The CDSR is considered the leading source of systematic reviews in medicine, with each Cochrane review developed by a professional editorial team and peer-reviewed to maintain high quality [17]. We used a PubMed search string for “acute lymphocytic leukemia” developed by a Cochrane Review on ALL [1]. We applied the following PubMed filters to the Cochrane Review search string: “Clinical Trial,” “Full Text,” “2015/01/01 – 2019/04/11,” “Humans,” “English,” and “Cancer.” The choice to exclude articles published before 2015 was made to allow an adequate buffer period for authors to begin adhering to TIDieR guidelines, since the guidelines were published in early 2014. The choice to exclude articles without a “Full text” permits a more accurate evaluation of the studies pulled in our search.

After implementing our CDSR-based PubMed search strategy, we established parameters for inclusion and exclusion of journal articles for final analysis of childhood ALL RCTs. To qualify for inclusion in our study, we used the following criteria: 1) report a randomized controlled trial, 2) contain only human subjects, 3) be published on or after 2015/01/01, 4) be published in English, 5) contain subjects of whom greater than 50% were diagnosed with ALL, and 6) contain subjects of whom greater than 50% of trial subjects were under 18 years of age. Criterion 5 was established as it was deemed unnecessary to exclude articles containing other childhood cancers if the majority of subjects were diagnosed with childhood ALL. Similarly, criterion 6 was established as it was deemed unnecessary to exclude articles containing young adults if the majority of subjects were under 18 years of age.

Each article generated from our CDSR-based PubMed search string was screened for eligibility independently by two investigators (NH and AH). Each excluded article received a label identifying how it did not meet criteria. A collaboration meeting was held between both investigators to review the list of articles for inclusion and exclusion. A consensus was established for each article. The articles that met inclusion criteria were analyzed independently for degree of adherence to the TIDieR checklist.

The TIDieR checklist is a 12-point document containing a brief description of each guideline [10]. It is designed as a checklist that is to be submitted with a publication, requiring authors to provide information on where each checklist item can be found in the publication [10]. A summarized version of the 12-point TIDieR checklist can be found in Table 1. A Google Form was used to score adherence to each item from the TIDieR checklist. Two investigators (NH and AH) independently scored all included articles for adherence to each item of the TIDieR checklist. Grading was achieved with a “Yes” or “No” scale for each item. A “Yes” was selected if an article reported all information required by TIDieR guidelines. Items 9 and 10 contained the option “N/A” (not applicable) since their presence within a study is conditional on the study design and execution. Additionally, we documented the publishing journal, funding, hypothesis, study type, intervention, blinding status, country, clinical trial registry status, and reported adherence to TIDieR. After the two investigators independently screened each article for TIDieR adherence, a second collaboration meeting was held and a consensus was established between the two investigators for each item on every article. A third investigator (MV) resolved discussions that were not easily resolved between the two primary analysts.

Results

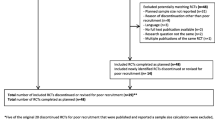

The PubMed search yielded 1546 articles. After independent screening and achieving consensus, 46 articles [18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63] were deemed to meet inclusion criteria for further evaluation of adherence to TIDieR (see Fig. 1). The most common reason for excluding an article was a wrong population (n = 1033), followed by wrong study design (n = 440). Examples of wrong population include studies that dealt with another disease process and studies with a majority of adult subjects. Examples of wrong study design include non-randomized trials and cohort studies.

Table 2 summarizes the demographic information of our included articles. Of the 46 articles examined, 35 (76.1%) reported pharmacological interventions, while the remaining 11 (23.9%) reported non-pharmacological interventions. 32 trials were not blinded or did not specify blinding type, with 10 being double-blinded and 4 being single-blinded. Thirty-one studies were conducted outside of the U.S., 13 were conducted in the U.S., and the remaining 2 were conducted both in the U.S and outside of the U.S. No studies stated adherence to TIDieR guidelines.

Figure 2 shows the number of properly reported TIDieR checklist items (out of 12) for the 46 included articles. On average, the articles adhered to TIDieR guidelines on 8.98/12 items, with a range of 5/12–12/12, and a median value of 9/12. Nine articles (19.6%) met full criteria for adherence to TIDieR guidelines. Of those, 7 reported non-pharmacological interventions, and 2 reported pharmacological interventions. Two articles reported only 5 of 12 checklist items correctly.

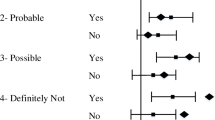

Figure 3 contains each item of the TIDieR checklist and the frequency of adherence among the articles. The most common item on the TIDieR checklist incompletely reported was item 5 (intervention provider), which was only present in 34.8% of articles. Item 7 (location) was reported in 50% of articles, while item 6 (mode of delivery) was adequately reported in only 52.2% of articles. Conversely, items 1 (what the intervention is) and 2 (rationale for the intervention) was adequately reported in 100% of the articles we analyzed, while item 8 (time and duration of delivery) was properly reported in 97.8% of articles.

Figure 4 shows a comparison of the year of publication of total articles screened versus articles that met TIDieR checklist standards. Years of publication of the 46 articles spanned from 2015 to 2019, while years of publication of the 9 articles that met full TIDieR checklist criteria spanned from 2015 to 2017. 2016 yielded the highest number of both total articles screened and articles that met TIDieR criteria.

Discussion

RCTs are the gold standard for advancement of medical research into clinical practice [6, 7]. TIDieR guidelines are intended to increase reproducibility of findings in clinical trials by standardizing reporting of RCTs across all areas of medicine [10]. Our results show that there is still much work to be done. Our study found less than  of RCTs that adhered to all TIDieR guidelines when reporting interventions. The average article missed at least 3 checklist items. Additionally, our study shows patterns of underreporting in specific elements of TIDieR. Almost two thirds of the articles neglected to properly report the title and qualifications of the person administering the intervention (item 5). Half of the articles failed to report the mode of delivery (item 6), and nearly half also failed to report a proper title or description of the location of the intervention (item 7). The most likely consequence of continuing inconsistent adherence to TIDieR guidelines is a lack of improvement in study design bias of future RCTs.

of RCTs that adhered to all TIDieR guidelines when reporting interventions. The average article missed at least 3 checklist items. Additionally, our study shows patterns of underreporting in specific elements of TIDieR. Almost two thirds of the articles neglected to properly report the title and qualifications of the person administering the intervention (item 5). Half of the articles failed to report the mode of delivery (item 6), and nearly half also failed to report a proper title or description of the location of the intervention (item 7). The most likely consequence of continuing inconsistent adherence to TIDieR guidelines is a lack of improvement in study design bias of future RCTs.

Literature shows that reporting of adherence of RCTs to proper intervention varies [8,9,10]. The TIDieR publication cites one study that found that only 11% of articles provided adequate information concerning the intervention [10]. Subsequent TIDieR studies have found similarly poor adherence rates to TIDieR guidelines. For example, Liljeberg et al. reported only 3% of articles that fulfilled all TIDieR criteria in their study [13]. Another study by Hacke et al. reported 0% out of 24 articles complete [64]. while this current study reports a relatively high total adherence rate of 19.6%. We found an average TIDieR adherence rate of 8.98/12, with 9 articles meeting full criteria. This statistic appears to reflect the findings of several previous TIDieR studies. For example, Hacke et al. reported an average TIDieR adherence rate of 61% (7.32/12), while McEwen et al. reported an average of 8.81/12 [15, 64].

A recent study found only 67% of pharmacological interventions were reported properly, compared to 29% of non-pharmacological interventions [10]. Interestingly, our findings showed much better adherence among non-pharmacological intervention studies. Of 11 non-pharmacological RCTs analyzed, 7 (63.6%) were adequately reported. Compare that with the remaining 35 articles reporting pharmacological intervention, of which only 2 (3.6%) were properly reported. Poor adherence in reporting the individual providing the intervention along with his or her qualifications (item 5) was noted among pharmacological RCTs, while good adherence to item 5 was noted among non-pharmacological RCTs. Several factors could be responsible. Many pharmacological RCTs were administered in an inpatient hospital setting. Perhaps authors of pharmacological RCTs assumed the qualifications of those administering the intervention were obvious in a hospital setting. Another consideration is the impact factor of journals from which non-pharmacological vs pharmacological RCTs were pulled, but this does not explain the difference in adherence between the two RCT groups. Further research may be warranted on the reasons for this pattern of adherence to TIDieR guidelines.

Our study suggests that adherence to TIDieR guidelines in reporting interventions in RCTs needs to improve. Furthermore, we found a systemic pattern of inconsistent intervention reporting in RCTs. Almost two thirds of RCTs are not reporting enough information about the location of the intervention to satisfy TIDieR guidelines. As stated in the TIDieR guide, reporting details about the location of intervention such as funding source, facility capabilities, volume of activity, etc. provides crucial and necessary information to whomever wishes to replicate the study [10]. Only half of studies reported enough information about the individual(s) that administered the intervention(s) to satisfy TIDieR guidelines. Properly reporting the title, certification and specific training of professionals delivering an intervention has significant influence on the reliability, validity, accuracy and precision of the RCTs.

We hypothesize that a solution to improve adherence to the TIDieR checklist is to increase awareness. Of the 46 articles analyzed in this study, none explicitly mentioned TIDieR or stated compliance with TIDieR guidelines. Furthermore, the data from Fig. 4 does not suggest a pattern of increasing adherence to the TIDieR checklist among articles based on their publication date. The TIDieR checklist was designed by a team of international professionals using evidence-based research [10] and should therefore be implemented by those who value peer-reviewed research methods.

Our study has limitations to discuss. It is primarily descriptive and is therefore more dependent upon experience and judgment than quantitative research. We attempted to understand that some bias is unavoidable in this type of research and therefore focused on reducing its effects [65, 66]. Although the TIDieR checklist is meant to standardize reporting and eliminate bias when evaluating adherence, our design could not eliminate the possibility of subjective interpretation when grading the adherence of RCTs. Although the TIDieR guide gives examples of successful reporting of several types of interventions for each TIDieR item, explanations are brief and rarely comprehensive enough to eliminate gray areas [10]. In these situations, we attempted to interpret the difficult determinations on a case-by-case basis. In discussing a publication similar to this present study, Liljeberg et al. noted the wide variety in degree of adherence of RCTs to TIDieR protocol and hypothesized that the degree of stringency of individual reviewers likely contributes to the disparity in findings [13]. We aimed to reduce bias by educating investigators with the same video series and discussions with a third party on the main elements of the TIDieR guidelines. Multiple samples were practiced between the two investigators, prior to the start of the study, to eliminate inaccurate interpretations of TIDieR guidelines. Further, both investigators were blinded to the other’s findings until disagreements were revealed at the completion of the study.

Another limitation is the amount of literature pertinent to ALL since the publication of TIDieR. To the knowledge of the authors, no TIDieR study has ever been conducted on RCTs of a single disease process before this current study. ALL was chosen due to its high degree of prevalence in the field of pediatric oncology [1, 2]. With that said, limiting the study to a specific disease limits available data. Whereas 46 articles were analyzed in this study, other TIDieR studies have double our amount or more from which to pull data.

We cannot extrapolate the results of our study to describe the adherence of RCTs involving other types of cancers.

Conclusion

The TIDieR checklist is an effective way of improving the reporting of interventions in randomized controlled trials. As new research continues to use TIDieR guidelines, it is our belief that reporting methods will continue to improve, allowing new interventions to be translated from clinical trials into clinical practice in a safe, efficient, and effective way. It is our hope that further research adhering to the TIDieR checklist will improve treatment of acute lymphocytic leukemia and all other diseases.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ALL:

-

Acute Lymphocytic Leukemia

- U.S.:

-

United States

- RCT:

-

Randomized Controlled Trial

- CONSORT:

-

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials

- TIDieR:

-

Template for Intervention Description and Replication

- CDSR:

-

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews

- NH:

-

Nicholas Hoffsommer, author

- AH:

-

Alexander Hoelscher, author

- MV:

-

Matt Vassar, author

- N/A:

-

Not applicable

References

Rensen N, Gemke RJ, van Dalen EC, Rotteveel J, Kaspers GJL. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis suppression after treatment with glucocorticoid therapy for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;89:2797.

Katz AJ, Chia VM, Schoonen WM, Kelsh MA. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia: an assessment of international incidence, survival, and disease burden. Cancer Causes Control. 2015;26:1627–42.

Terwilliger T, Abdul-Hay M. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a comprehensive review and 2017 update. Blood Cancer J. 2017;7:e577.

Cools J. Improvements in the survival of children and adolescents with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Haematologica. 2012;97:635.

Hunger SP, Lu X, Devidas M, Camitta BM, Gaynon PS, Winick NJ, et al. Improved survival for children and adolescents with acute lymphoblastic leukemia between 1990 and 2005: a report from the children’s oncology group. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1663–9.

Kabisch M, Ruckes C, Seibert-Grafe M, Blettner M. Randomized controlled trials: part 17 of a series on evaluation of scientific publications. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2011;108:663–8.

Hariton E, Locascio JJ. Randomised controlled trials - the gold standard for effectiveness research: Study design: randomised controlled trials. BJOG. 2018;125:1716.

Altman DG. Better reporting of randomised controlled trials: the CONSORT statement. BMJ. 1996;313:570–1.

Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D, CONSORT Group. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ. 2010;340:c332.

Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, Milne R, Perera R, Moher D, et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ. 2014;348:g1687.

Sims MT, Henning NM, Wayant CC, Vassar M. Do emergency medicine journals promote trial registration and adherence to reporting guidelines? A survey of “Instructions for Authors”. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2016;24:137.

Juszczak E, Altman DG, Hopewell S, Schulz K. Reporting of Multi-Arm Parallel-Group Randomized Trials: Extension of the CONSORT 2010 Statement. JAMA. 2019;321:1610–20.

Liljeberg E, Andersson A, Lövestam E, Nydahl M. Incomplete descriptions of oral nutritional supplement interventions in reports of randomised controlled trials. Clin Nutr. 2018;37:61–71.

Jones EL, Lees N, Martin G, Dixon-Woods M. How Well Is Quality Improvement Described in the Perioperative Care Literature? A Systematic Review. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2016;42:196–206.

McEwen D, O’Neil J, Miron-Celis M, Brosseau L. Content Reporting in Post-Stroke Therapeutic Circuit-Class Exercise Programs in randomized control trials. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2019;26:281–7.

Sood A, Ghosh AK. Literature search using PubMed: an essential tool for practicing evidence- based medicine. J Assoc Physicians India. 2006;54:303–8.

Synnot AJ, Tong A, Bragge P, Lowe D, Nunn JS, O’Sullivan M, et al. Selecting, refining and identifying priority Cochrane Reviews in health communication and participation in partnership with consumers and other stakeholders. Health Res Policy Syst. 2019;17:45.

Bordbar M, Shakibazad N, Fattahi M, Haghpanah S, Honar N. Effect of ursodeoxycholic acid and vitamin E in the prevention of liver injury from methotrexate in pediatric leukemia. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2018;29:203–9.

Meza-Arroyo J, Bravo-Cuellar A, Jave-Suárez LF, Hernández-Flores G, Ortiz-Lazareno P, Aguilar-Lemarroy A, et al. Pentoxifylline Added to Steroid Window Treatment Phase Modified Apoptotic Gene Expression in Pediatric Patients With Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2018;40:360–7.

Kaspers GJL, Niewerth D, Wilhelm BAJ, Scholte-van Houtem P, Lopez-Yurda M, Berkhof J, et al. An effective modestly intensive re-induction regimen with bortezomib in relapsed or refractory paediatric acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2018;181:523–7.

Tunyapanit W, Chelae S, Laoprasopwattana K. Does ciprofloxacin prophylaxis during chemotherapy induce intestinal microflora resistance to ceftazidime in children with cancer? J Infect Chemother. 2018;24:358–62.

Tulstrup M, Frandsen TL, Abrahamsson J, Lund B, Vettenranta K, Jonsson OG, et al. Individualized 6-mercaptopurine increments in consolidation treatment of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: A NOPHO randomized controlled trial. Eur J Haematol. 2018;100:53–60.

Mondelaers V, Suciu S, De Moerloose B, Ferster A, Mazingue F, Plat G, et al. Prolonged versus standard native E. coli asparaginase therapy in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia and non-Hodgkin lymphoma: final results of the EORTC-CLG randomized phase III trial 58951. Haematologica. 2017;102:1727–38.

Locatelli F, Bernardo ME, Bertaina A, Rognoni C, Comoli P, Rovelli A, et al. Efficacy of two different doses of rabbit anti-T-lymphocyte globulin to prevent graft-versus-host disease in children with haematological malignancies transplanted from an unrelated donor: a multicentre, randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:1126–36.

Eapen M, Kurtzberg J, Zhang M-J, Hattersely G, Fei M, Mendizabal A, et al. Umbilical Cord Blood Transplantation in Children with Acute Leukemia: Impact of Conditioning on Transplantation Outcomes. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2017;23:1714–21.

Hardy KK, Embry L, Kairalla JA, Helian S, Devidas M, Armstrong D, et al. Neurocognitive Functioning of Children Treated for High-Risk B-Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Randomly Assigned to Different Methotrexate and Corticosteroid Treatment Strategies: A Report From the Children’s Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:2700–7.

Tram Henriksen L, Gottschalk Højfeldt S, Schmiegelow K, Frandsen TL, Skov Wehner P, Schrøder H, et al. Prolonged first-line PEG-asparaginase treatment in pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia in the NOPHO ALL2008 protocol-Pharmacokinetics and antibody formation. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2017;64. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.26686.

Toksvang LN, De Pietri S, Nielsen SN, Nersting J, Albertsen BK, Wehner PS, et al. Hepatic sinusoidal obstruction syndrome during maintenance therapy of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia is associated with continuous asparaginase therapy and mercaptopurine metabolites. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2017;64. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.26519.

Tolbert JA, Bai S, Abdel-Rahman SM, August KJ, Weir SJ, Kearns GL, et al. Pharmacokinetics of two 6-mercaptopurine liquid formulations in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2017;64. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.26465.

Zupanec S, Jones H, McRae L, Papaconstantinou E, Weston J, Stremler R. A Sleep Hygiene and Relaxation Intervention for Children With Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. Cancer Nurs. 2017;40:488–96.

Sands S, Ladas EJ, Kelly KM, Weiner M, Lin M, Ndao DH, et al. Glutamine for the treatment of vincristine-induced neuropathy in children and adolescents with cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25:701–8.

Levinsen M, Harila-Saari A, Grell K, Jonsson OG, Taskinen M, Abrahamsson J, et al. Efficacy and Toxicity of Intrathecal Liposomal Cytarabine in First-line Therapy of Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2016;38:602–9.

Bardellini E, Amadori F, Majorana A. Oral hygiene grade and quality of life in children with chemotherapy-related oral mucositis: a randomized study on the impact of a fluoride toothpaste with salivary enzymes, essential oils, proteins and colostrum extract versus a fluoride toothpaste without menthol. Int J Dent Hyg. 2016;14:314–9.

Williams LK, McCarthy MC, Burke K, Anderson V, Rinehart N. Addressing behavioral impacts of childhood leukemia: A feasibility pilot randomized controlled trial of a group videoconferencing parenting intervention. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2016;24:61–9.

Li M-J, Liu H-C, Yen H-J, Jaing T-H, Lin D-T, Yang C-P, et al. Treatment for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia in Taiwan: Taiwan Pediatric Oncology Group ALL-2002 study emphasizing optimal reinduction therapy and central nervous system preventive therapy without cranial radiation. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2017;64:234–41.

Li R, Donnella H, Knouse P, Raber M, Crawford K, Swartz MC, et al. A randomized nutrition counseling intervention in pediatric leukemia patients receiving steroids results in reduced caloric intake. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2017;64:374–80.

Lin H, Zhou S, Zhang D, Huang L. Evaluation of a nurse-led management program to complement the treatment of adolescent acute lymphoblastic leukemia patients. Appl Nurs Res. 2016;32:e1–5.

Bardellini E, Amadori F, Schumacher RF, D’Ippolito C, Porta F, Majorana A. Efficacy of a Solution Composed by Verbascoside, Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) and Sodium Hyaluronate in the Treatment of Chemotherapy-induced Oral Mucositis in Children With Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2016;38:559–62.

Han Y, Zhang F, Wang J, Zhu Y, Dai J, Bu Y, et al. Application of Glutamine-enriched nutrition therapy in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nutr J. 2016;15:65.

Warris LT, van den Akker ELT, Bierings MB, van den Bos C, Zwaan CM, Sassen SDT, et al. Acute Activation of Metabolic Syndrome Components in Pediatric Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Patients Treated with Dexamethasone. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0158225.

Conklin HM, Ashford JM, Clark KN, Martin-Elbahesh K, Hardy KK, Merchant TE, et al. Long-Term Efficacy of Computerized Cognitive Training Among Survivors of Childhood Cancer: A Single-Blind Randomized Controlled Trial. J Pediatr Psychol. 2017;42:220–31.

Warris LT, van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM, Aarsen FK, Pluijm SMF, Bierings MB, van den Bos C, et al. Hydrocortisone as an Intervention for Dexamethasone-Induced Adverse Effects in Pediatric Patients With Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: Results of a Double-Blind, Randomized Controlled Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:2287–93.

Larsen EC, Devidas M, Chen S, Salzer WL, Raetz EA, Loh ML, et al. Dexamethasone and High-Dose Methotrexate Improve Outcome for Children and Young Adults With High-Risk B-Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: A Report From Children’s Oncology Group Study AALL0232. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:2380–8.

Michel G, Galambrun C, Sirvent A, Pochon C, Bruno B, Jubert C, et al. Single- vs double-unit cord blood transplantation for children and young adults with acute leukemia or myelodysplastic syndrome. Blood. 2016;127:3450–7.

Abdulrhman MA, Hamed AA, Mohamed SA, Hassanen NAA. Effect of honey on febrile neutropenia in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: A randomized crossover open-labeled study. Complement Ther Med. 2016;25:98–103.

Möricke A, Zimmermann M, Valsecchi MG, Stanulla M, Biondi A, Mann G, et al. Dexamethasone vs prednisone in induction treatment of pediatric ALL: results of the randomized trial AIEOP-BFM ALL 2000. Blood. 2016;127:2101–12.

Lucchese A, Matarese G, Manuelli M, Ciuffreda C, Bassani L, Isola G, et al. Reliability and efficacy of palifermin in prevention and management of oral mucositis in patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a randomized, double-blind controlled clinical trial. Minerva Stomatol. 2016;65:43–50.

Asselin BL, Devidas M, Chen L, Franco VI, Pullen J, Borowitz MJ, et al. Cardioprotection and Safety of Dexrazoxane in Patients Treated for Newly Diagnosed T-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia or Advanced-Stage Lymphoblastic Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma: A Report of the Children’s Oncology Group Randomized Trial Pediatric Oncology Group 9404. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:854–62.

de Beaumais Tiphaine A, Hjalgrim LL, Nersting J, Breitkreutz J, Nelken B, Schrappe M, et al. Evaluation of a pediatric liquid formulation to improve 6-mercaptopurine therapy in children. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2016;83:1–7.

Place AE, Stevenson KE, Vrooman LM, Harris MH, Hunt SK, O’Brien JE, et al. Intravenous pegylated asparaginase versus intramuscular native Escherichia coli L-asparaginase in newly diagnosed childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (DFCI 05-001): a randomised, open-label phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:1677–90.

Conklin HM, Ogg RJ, Ashford JM, Scoggins MA, Zou P, Clark KN, et al. Computerized Cognitive Training for Amelioration of Cognitive Late Effects Among Childhood Cancer Survivors: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:3894–902.

Lucchese A, Matarese G, Ghislanzoni LH, Gastaldi G, Manuelli M, Gherlone E. Efficacy and effects of palifermin for the treatment of oral mucositis in patients affected by acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2016;57:820–7.

Elbarbary NS, Ismail EAR, Farahat RK, El-Hamamsy M. ω-3 fatty acids as an adjuvant therapy ameliorates methotrexate-induced hepatotoxicity in children and adolescents with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: A randomized placebo-controlled study. Nutrition. 2016;32:41–7.

Gonzalez-Ramella O, Ortiz-Lazareno PC, Jiménez-López X, Gallegos-Castorena S, Hernández-Flores G, Medina-Barajas F, et al. Pentoxifylline during steroid window phase at induction to remission increases apoptosis in childhood with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Clin Transl Oncol. 2016;18:369–74.

Ruble K, Scarvalone S, Gallicchio L, Davis C, Wells D. Group Physical Activity Intervention for Childhood Cancer Survivors: A Pilot Study. J Phys Act Health. 2016;13:352–9.

Borowitz MJ, Wood BL, Devidas M, Loh ML, Raetz EA, Salzer WL, et al. Prognostic significance of minimal residual disease in high risk B-ALL: a report from Children’s Oncology Group study AALL0232. Blood. 2015;126:964–71.

Hagag AA, AbdElaal AM, Elfaragy MS, Hassan SM, Elzamarany EA. Therapeutic value of black seed oil in methotrexate hepatotoxicity in Egyptian children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Infect Disord Drug Targets. 2015;15:64–71.

Bradfield SM, Sandler E, Geller T, Tamura RN, Krischer JP. Glutamic acid not beneficial for the prevention of vincristine neurotoxicity in children with cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62:1004–10.

Chan CWH, Lam LW, Li CK, Cheung JSS, Cheng KKF, Chik KW, et al. Feasibility of psychoeducational interventions in managing chemotherapy-associated nausea and vomiting (CANV) in pediatric oncology patients. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2015;19:182–90.

Henriksen LT, Harila-Saari A, Ruud E, Abrahamsson J, Pruunsild K, Vaitkeviciene G, et al. PEG-asparaginase allergy in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia in the NOPHO ALL2008 protocol. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62:427–33.

Hastings C, Gaynon PS, Nachman JB, Sather HN, Lu X, Devidas M, et al. Increased post-induction intensification improves outcome in children and adolescents with a markedly elevated white blood cell count (≥200 × 10(9) /l) with T cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia but not B cell disease: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Br J Haematol. 2015;168:533–46.

Whitlow PG, Saboda K, Roe DJ, Bazzell S, Wilson C. Topical analgesia treats pain and decreases propofol use during lumbar punctures in a randomized pediatric leukemia trial. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62:85–90.

Karachunskiy A, Tallen G, Roumiantseva J, Lagoiko S, Chervova A, von Stackelberg A, et al. Reduced vs. standard dose native E. coli-asparaginase therapy in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: long-term results of the randomized trial Moscow-Berlin 2002. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2019;145:1001–12.

Hacke C, Nunan D, Weisser B. Do Exercise Trials for Hypertension Adequately Report Interventions? A Reporting Quality Study. Int J Sports Med. 2018;39:902–8.

Booth A, Lewin S, Glenton C, Munthe-Kaas H, Toews I, Noyes J, et al. Applying GRADE-CERQual to qualitative evidence synthesis findings-paper 7: understanding the potential impacts of dissemination bias. Implement Sci. 2018;13 Suppl 1:12.

Toews I, Glenton C, Lewin S, Berg RC, Noyes J, Booth A, et al. Extent, Awareness and Perception of Dissemination Bias in Qualitative Research: An Explorative Survey. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0159290.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Conflict of interests

This study received no financial support, and the authors have no conflict of interests to report.

Funding

This study was not funded.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors made substantial contributions to the conception of the study. SJ and MV designed the study. NH and AH acquired data. NH and AH analysed data. All authors had a substantial role in drafting the manuscript. All authors have approved the final version and have agreed to be personally accountable for the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jellison, S., Hoffsommer, N., Hoelscher, A. et al. Evaluating Fidelity of reporting in randomized controlled trials on childhood acute lymphocytic leukemia. Appl Cancer Res 40, 5 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41241-020-00088-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41241-020-00088-9