Abstract

Mechanical stress maintains tissue homeostasis by regulating many cellular functions including cell proliferation, differentiation, and inflammation and immune responses. In inflammatory microenvironments, macrophages in mechanosensitive tissues receive mechanical signals that regulate various cellular functions and inflammatory responses. Macrophage function is affected by several types of mechanical stress, but the mechanisms by which mechanical signals influence macrophage function in inflammation, such as the regulation of interleukin-1β by inflammasomes, remain unclear. In this review, we describe the role of mechanical stress in macrophage and monocyte cell function.

Similar content being viewed by others

Mechanical stress and tissue homeostasis

Mechanical stress maintains tissue homeostasis by regulating cellular functions such as development, inflammation, bone remodeling, and tumor progression [1,2,3,4]. Most cells in connective tissue receive various mechanical stresses such as stretch force, compressive force, shear stress, and hydrostatic pressure [2]. Several tissues, such as the heart, lung, bone, gut, and periodontal ligament, are affected by mechanical stress, and cells in these tissues are involved in tissue homeostasis [5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12]. Integrin, voltage-gated Ca2+ channels, and focal adhesion kinase (FAK) are known as mechanosensors that sense mechanical stress in cells. In addition to these sensors, cytoskeleton dynamics affect how cells respond to mechanical force [2]. Mechanical stress activates signaling pathway downstream of mechanosensors, such as the mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase pathway or cytoskeletal reorganization, which results in expression of specific genes or post-transcriptional gene regulation [13]. While physiological mechanical stress maintains tissue homeostasis, excessive force or absence of mechanical stress causes various pathological changes such as pro-inflammatory responses and tissue atrophy [14]. For example, excessive mechanical stimuli by mechanical ventilation causes lung inflammation [15]. Mechanical stress from excessive occlusal force or orthodontic tooth movement in periodontal tissue promotes inflammation of periodontal tissue [12, 16]. Low shear stress because of stagnant blood flow in arteries promotes inflammation and is a factor in arteriosclerosis [17]. Loss of occlusal force in periodontal tissues causes atrophy of periodontal ligament tissue and induces interleukin (IL)-1β gene expression [18, 19]. Therefore, appropriate mechanical stress is needed to maintain homeostasis in physiological microenvironments.

Macrophages

Macrophages have a central role in immune reactions through phagocytosis of pathogenic microorganisms, by releasing inflammatory mediators, such as interleukin, and by inducing inflammation [20]. Macrophages not only eliminate pathogenic bacteria but also maintain tissue homeostasis by removing apoptotic cells and repairing tissue following inflammation [21]. Macrophages already present in specific tissue are called tissue-resident macrophages [22]. Tissues-resident macrophages are derived from the yolk sac at the embryonic stage, are replicated in tissues to maintain cell number, and have different morphology and function depending on the tissue [22]. For example, macrophages in the lung are called alveolar macrophages, those in the liver are called Kupffer cells, and macrophage-like microglia operate in the nervous system. The diversity of tissue-resident macrophages is related to interactions with cells in supporting tissues [22]. However, in the case of tissue injury or infection, monocytes derived from bone marrow circulating in peripheral blood migrate to the affected tissue, differentiate into macrophages, and are involved in the inflammatory response [23]. The cellular functions of tissue-resident macrophages and peripheral blood-derived macrophages are affected by the tissue-specific microenvironment, which can create many types of mechanical stress on cells [24, 25]. Stiffness and topography, which are mechanical properties of the extracellular matrix, regulate the differentiation, proliferation, and function of macrophages. In addition, macrophages present in these tissues are exposed to dynamic mechanical loading, such as stretch and compression, not only continuously but also cyclically. In this review, we describe the role of mechanical loading in macrophage and monocyte cell function.

Mechanical force and macrophages

It has been reported that mechanical stress, such as stretch and compression, regulate monocyte/macrophage function in terms of cytokine and proteinase expression and cell differentiation as shown in Table 1. Cyclic stretch promotes the secretion of IL-6, IL-8, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α in human alveolar macrophages, human monocyte-derived macrophages, and a human macrophage-like cell line (THP-1) [26]. In THP-1, cyclic stretch induces cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 gene expression, and a combination of cyclic stretch and titanium particles promotes prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) production [27]. In rat peritoneal macrophages, static stretch induces inflammatory cytokine gene expression such as inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and IL-6 [28]. On the other hand, there are some reports suggesting that mechanical stress does not particularly affect cytokine production. In rat alveolar macrophages, cyclic stretch does not affect TNF-α and IL-6 secretion [29]. In a mouse macrophage-like cell line (RAW264.7) and bone marrow-derived macrophages, cyclic biaxial stretch does not affect the expression of IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, and COX2 [30]. Macrophages are involved in the remodeling of the extracellular matrix via secretion of matrix metalloproteinase (MMP), and cyclic stretch is involved in the regulation of secretion. In human monocyte-derived macrophages, cyclic stretch induces the expression of MMP-1 and MMP-3 [31]. Cyclic stretch also regulates the differentiation of macrophages into osteoclasts. In human monocytes, cyclic stretch promotes osteoclast differentiation by receptor activator for nuclear factor-κB ligand (RANKL) [32]. On the other hand, in RAW264.7 cells, cyclic stretch inhibits osteoclast differentiation by RANKL [33,34,35], which suggests that different responses depend on the cell differentiation stage and stretch condition. Compressive stimulation also seems to be involved in osteoclast differentiation. In RAW 264.7 and bone marrow-derived macrophages, continuous compression force promotes osteoclast differentiation, and release from compressive force is involved in the suppression of osteoclast differentiation [36,37,38]. Stretch and compressive stimulation act on tissue-resident macrophages and bone marrow-derived macrophages in peripheral tissues, such as the periodontal ligament, lung, and bone, and the response by these macrophages depends on the surrounding environment, including the scaffold and type of mechanical stress.

Experimental methods of mechanical stimulation to macrophages

Some methods have been reported to reproduce mechanical stimulus received by cells in tissue in vitro. In particular, there are many reports on stretch stimulation devices. Devices for verifying the in vitro effect of physical changes of tissues from stretching on macrophages have been used. One cell extension device that is often used is by stretching a silicon resin chamber under negative pressure. Devices that extend the silicon chamber using computer-controlled motors and devices, such as a four-point bending system, are also used. By changing the setting of these devices, it is possible to adjust cyclic and static stimulation, the cell elongation rate, the extension frequency, and the devices can mimic the stimulation that cells receive in the target tissue. In our laboratory, we have investigated the response of cells assuming a periodontal ligament tissue with mechanical stress using a cell-stretching device with a computer-controlled motor for stretching the silicon resin chamber in a controlled (5% CO2) humidified atmosphere (STB-140 STREX cell stretch system (STREX Co., Osaka, Japan)) [39] (Fig. 1). This device can set an extension rate (2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 15, 20%) and an extension frequency (1, 2, 6, 10, 20, 30, 60 cycles/min) to investigate the cellular response to mechanical stress under various conditions.

NLRP3 inflammasome

IL-1β is secreted from macrophages and promotes the secretion of various inflammatory cytokines during inflammation [40, 41]. The inflammasome, a group of cytosolic protein complexes, strictly controls IL-1β secretion from macrophages [42]. Inflammasomes are a group of cytosolic protein complexes that regulate the activation of caspase-1, convert precursor pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18 into their mature forms, and consist of cytoplasmic receptors such as a nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain (NOD)-like receptor protein (NLRP), the apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a caspase recruitment domain (ASC), and pro-caspase-1 [43]. Inflammasomes are classified into several types depending on the activated intracellular receptors [44]. The inflammasome NLRP3 reacts to extracellular adenosine triphosphate (ATP), β-amyloid, and cholesterol [45,46,47,48]. The activation mechanism of the inflammasome begins with the induction of pro-IL-1β and constitutive inflammasome molecules (signal 1). Macrophages recognize bacterial cell components, such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS) or inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α and IL-1β, which in turn induce the expression of pro-IL-1β and constitutive inflammasome molecules via nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) signaling. Next, NLRP3 inflammasome components are assembled after sensing danger signals, such as pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) and damage-related molecular patterns (DAMPs), and activate caspase-1, which processes pro-IL-1β into mature IL-1β (signal 2).

Relationship between mechanical stress and the NLRP3 inflammasome

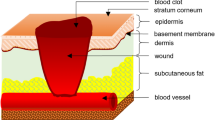

There are a few reports on the relationship between mechanical stress and the NLRP3 inflammasome. Wu et al. reported that cyclic stretch activates the NLRP3 inflammasome via mitochondrial ROS production in tissue-resident mouse alveolar macrophages and suggested that this mechanism may be related to lung inflammation induced by mechanical ventilation [49]. This report indicates that mechanical stress may be a risk factor of NLRP3 inflammasome activation. While Stojadinovic et al. reported that sustained compressive force to epidermal tissue resulted in enhanced protein expression of NLRP3 and caspase-1, but decreased the expression of IL-1β [50]. Therefore, the relationship between mechanical stress and inflammasome signaling is still unclear. Recently, we found that cyclic stretch suppresses the NLRP3 inflammasome in macrophages [51] and will introduce our new findings in the latter part of this paper (Fig. 2).

NLRP3 inflammasome pathways and putative mechanism by which cyclic stretch negatively regulates IL-1β secretion in murine macrophages. Treatment with LPS activates NF-κB signaling via toll-like receptor (TLR) 4 (signal 1) and induces the expression of NLRP3 and pro-IL-1β. Extracellular ATP activates inflammasomes via P2X7 receptors (signal 2) and induces the activation of caspase-1, which leads to the secretion of IL-1β and pyroptosis. Cyclic stretch does not interfere with NF-κB signaling (signal 1), but inhibits the activation of caspase-1 (signal 2) by attenuating the AMP kinase pathway

Suppression of IL-1β secretion by cyclic stretch in macrophages

Extracellular ATP released from injured cells or bacteria is recognized by the macrophage P2X7 receptor, which causes a loss of potassium ions and activates the NLRP3 inflammasome [52, 53]. ATP triggers IL-1β secretion in LPS-primed J774.1 mouse macrophages (Fig. 3a), but excessive inflammation by the NLRP3 inflammasome may disrupt tissue homeostasis [42]. We examined the relationship between mechanical stress and the NLRP3 inflammasome using a cyclic stretch system. LPS-primed J774.1 cells and mouse bone marrow-derived macrophages were exposed to a cyclic stretch of 20% elongation at a frequency of 10 cycles/min, which markedly suppressed IL-1β secretion (Fig. 3), suggesting that cyclic stretch inhibits the NLRP3 inflammasome signaling pathway.

Cyclic stretch inhibits ATP-stimulated IL-1β secretion in LPS-primed macrophages. The murine macrophage cell line J774.1 (a) and mouse bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDM) (b) was primed with 100 ng/mL of E. coli LPS for 4 h followed by stimulation with 1 mM ATP for 2 h in the continuous presence of LPS. Cells were exposed to cyclic stretch of 20% elongation at a frequency of 10 cycles/min for the first 2 h after the addition of LPS. Significance is indicated (*P < 0.05 significantly different from the positive control). CS, cyclic stretch. ND, not detected

Cyclic stretch does not inhibit the NF-κB pathway in macrophages

Expression of NLRP3 inflammasome-related molecules, such as NLRP3 and pro-IL-1β, is required for the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome. These molecules are induced by the activation of the NF-kB pathway by bacterial components such as LPS (signal 1) [54]. We investigated whether cyclic stretch inhibits the NF-kB pathway. Inhibitor of κB (IκB), which binds to the NF-κB complex in the cytoplasm at steady state, is phosphorylated by inhibitor of κB kinase (IKK) and degraded via a ubiquitin-proteasome degradation system when a stimulus, such as LPS, is added to the cells [55]. Figure 4a shows that cyclic stretch had no effect on LPS-induced IκB time-dependent degradation and re-expression. Liberated NF-κB translocates to the nucleus and binds to the promoters of NF-κB target genes including pro-inflammatory cytokines and NLRP3 inflammasome-related genes [56, 57]. We also examined whether cyclic stretch inhibits the transcriptional activity of NF-κB in the nucleus. Proteins from the nucleus of J774.1 macrophages primed by LPS were extracted and examined using an NF-κB p65 DNA-binding ELISA method. As the result, cyclic stretch did not significantly affect LPS-induced NF-κB p65-binding activity (Fig. 4b), which suggests that suppression of IL-1β secretion by cyclic stretch is independent of NF-κB signaling (signal 1).

Cyclic stretch does not alter the LPS-induced NF-κB signaling pathway. a J774.1 cells were exposed to cyclic stretch of 20% elongation at a frequency of 10 cycles/min with 100 ng/mL LPS for the indicated times. Cell lysates were analyzed by western blotting with anti-IκB-α. An antibody against β-actin was used as a control. b J774.1 cells were exposed to cyclic stretch of 20% elongation at a frequency of 10 cycles/min for the first 2 h during treatment with 100 ng/mL LPS for 4 h. Nuclear proteins were extracted from cells and an NF-κB ELISA assay was performed. CS, cyclic stretch. ns, not significant

Cyclic stretch suppresses caspase-1 activation in macrophages

The NLRP3 inflammasome signal 2 consists of a signal cascade that begins with the recognition of danger signals [45]. Activation of NLRP3 inflammation is induced by potassium ion efflux via ATP binding to P2X7 cell membrane receptors and reactive oxygen species (ROS) production in the cytoplasm, which in turn converts pro-caspase-1 to active caspase-1 [52]. Therefore, we examined the effect of cyclic stretch on the activation of caspase-1 using western blotting and a FLICA probe-conjugated FAM, which specifically detects active caspase-1 in the cytoplasm. Expression of released activated caspase-1 by inflammasome activation and the number of cells with the active form of caspase-1 in the cytoplasm were suppressed by cyclic stretch in ATP-stimulated LPS-primed J774.1 cells (Fig. 5).

Cyclic stretch inhibits LPS/ATP-induced activation of caspase-1. J774.1 cells were exposed to cyclic stretch of 20% elongation at a frequency of 10 cycles/min for the first 2 h during treatment with 100 ng/mL LPS for 4 h followed by stimulation with ATP for 2 h in the continuous presence of LPS. a Concentrated supernatants were analyzed by western blotting with specific antibodies to caspase-1 and IL-1β. b Cells were labeled with a FLICA probe conjugated with FAM (green) and nuclei were visualized by staining with Hoechst 33342 (blue) (magnification, × 200; scale bars are 50 μm). The negative control (Non.) was not treated with LPS, ATP, or cyclic stretch. CS, cyclic stretch

AMPK controls the NLRP3 inflammasome

Adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) signaling is a key regulator of cellular energy homeostasis. This signaling pathway mainly functions as the cell’s energy sensor and controls various functions such as metabolic regulation, cytoskeleton regulation, and the inflammatory response [58, 59]. AMPK regulates the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome with aging, and activation of AMPK signaling may be a therapeutic target for age-related diseases. Autophagy promotion, mitochondrial homeostasis, endoplasmic reticulum stress regulation, and SIRT1 activation by AMPK suppresses NLRP3 inflammasome activation [60]. Activation of the AMPK signaling pathway is involved in NLRP3 inflammasome suppression, but some reports suggest that inhibition of AMPK activation suppresses NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Phosphorylation of AMPK activates the NLRP3 inflammasome and promotes IL-1β secretion and pyroptosis, and suppression of AMPK phosphorylation inhibits the NLRP3 inflammasome [61]. Piperine (an alkaloid contained in black pepper) inhibits AMPK phosphorylation, which accompanies extracellular ATP stimulation in mouse macrophages J774A.1 and human proximal tubular cell line HK-2 cells, and suppresses NLRP3 inflammasome activation [62, 63]. In addition, in mice placed on a ketogenic diet, reduction of AMPK phosphorylation in the retina and concomitant suppression of NLRP3 inflammasome are observed [64]. We found that cyclic stretch suppresses macrophage NLRP3 inflammasome via inhibition of ATP-triggered AMPK phosphorylation. AMPK phosphorylation in LPS-primed macrophages was significantly enhanced by adding extracellular ATP, but cyclic stretch suppressed this phosphorylation, which indicates that AMPK signaling participates in inflammasome signaling and mechanical stress. Phosphorylation of AMPK is regulated by cyclic stretch [65,66,67], and mechanical stress regulates AMPK signaling in inflamed and normal cells. Therefore, mechanical stress is a factor that regulates NLRP3 inflammasome via AMPK signaling.

Conclusion

Although the role of mechanical stress in the inflammatory response is still controversial, our findings provide insight into the maintenance of homeostasis through the prevention of excessive inflammasome activation.

Abbreviations

- AMPK:

-

Adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase

- ASC:

-

Apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a caspase recruitment domain

- ATP:

-

Adenosine triphosphate

- DAMPs:

-

Damage/danger-associated molecular patterns

- FAK:

-

Focal adhesion kinase

- IKK:

-

Inhibitor of kappa B kinase

- IL:

-

Interleukin

- IκB:

-

Inhibitor of kappa B

- LDH:

-

Lactate dehydrogenase

- LPS:

-

Lipopolysaccharide

- MAP kinase:

-

Mitogen-activated protein kinase

- NF-κB:

-

Nuclear factor-kappa B

- NLRP:

-

Nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor protein

- NLRP3:

-

NLR family, pyrin domain containing 3

- PAMPs:

-

Pathogen-associated molecular patterns

- ROS:

-

Reactive oxygen species

- TNF-α:

-

Tumor necrosis factor-α

References

Gillespie PG, Walker RG. Molecular basis of mechanosensory tr ansduction. Nature. 2001;413:194–202.

Wang JH, Thampatty BP. An introductory review of cell mechanobiology. Biomech Model Mechanobiol. 2006;5:1–16.

Schwartz MA, DeSimone DW. Cell adhesion receptors in mechanotransduction. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2008;20:551–6.

Broders-Bondon F, Nguyen Ho-Bouldoires TH, Fernandez-Sanchez ME, Farge E. Mechanotransduction in tumor progression: the dark side of the force. J Cell Biol. 2018;217:1571–87.

Buyandelger B, Mansfield C, Knöll R. Mechano-signaling in heart failure. Pflugers Arch. 2014;466:1093–9.

Lyon RC, Zanella F, Omens JH, Sheikh F. Mechanotransduction in cardiac hypertrophy and failure. Circ Res. 2015;116:1462–76.

Spieth PM, Bluth T, Gama De Abreu M, Bacelis A, Goetz AE, Kiefmann R. Mechanotransduction in the lungs. Minerva Anestesiol. 2014;80:933–41.

Shi XZ. Mechanical regulation of gene expression in gut smooth muscle cells. Front Physiol. 2017;8:1000.

Papachristou DJ, Papachroni KK, Basdra EK, Papavassiliou AG. Signaling networks and transcription factors regulating mechanotransduction in bone. BioEssays. 2009;31:794–804.

Knapik DM, Perera P, Nam J, Blazek AD, Rath B, Leblebicioglu B, Das H, Wu LC, Hewett TH, Agarwal SK Jr, Robling AG, Flanigan DC, Lee BS, Agarwal S. Mechanosignaling in bone health, trauma and inflammation. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2014;20:970–85.

Spyropoulou A, Karamesinis K, Basdra EK. Mechanotransduction pathways in bone pathobiology. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1852:1700–8.

McCulloch CA, Lekic P, McKee MD. Role of physical forces in regulating the form and function of the periodontal ligament. Periodontol 2000. 2000;24:56–72.

Iqbal J, Zaidi M. Molecular regulation of mechanotransduction. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;328:751–5.

Nguyen QT, Jacobsen TD, Chahine NO. Effects of inflammation on multiscale biomechanical properties of cartilaginous cells and tissues. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 2017;3:2644–56.

Silva PL, Negrini D, Rocco PR. Mechanisms of ventilator-induced lung injury in healthy lungs. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2015;29:301–13.

Nakatsu S, Yoshinaga Y, Kuramoto A, Nagano F, Ichimura I, Oshino K, Yoshimura A, Yano Y, Hara Y. Occlusal trauma accelerates attachment loss at the onset of experimental periodontitis in rats. J Periodontal Res. 2014;49:314–22.

Bryan MT, Duckles H, Feng S, Hsiao ST, Kim HR, Serbanovic-Canic J, Evans PC. Mechanoresponsive networks controlling vascular inflammation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2014;34:2199–205.

Boonpratham S, Kanno Z, Soma K. Occlusal stimuli regulate interleukin-1 beta and FGF-2 expression in rat periodontal ligament. J Med Dent Sci. 2007;54:71–7.

Choi JW, Arai C, Ishikawa M, Shimoda S, Nakamura Y. Fiber system degradation, and periostin and connective tissue growth factor level reduction, in the periodontal ligament of teeth in the absence of masticatory load. J Periodontal Res. 2011;46:513–21.

Gordon S. The macrophage: past, present and future. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37(Suppl 1):S9–17.

Mosser DM, Edwards JP. Exploring the full spectrum of macrophage activation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:958–69.

Lavin Y, Mortha A, Rahman A, Merad M. Regulation of macrophage development and function in peripheral tissues. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15:731–44.

Shi C, Pamer EG. Monocyte recruitment during infection and inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:762–74.

McWhorter FY, Davis CT, Liu WF. Physical and mechanical regulation of macrophage phenotype and function. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2015;72:1303–16.

Mennens SFB, van den Dries K, Cambi A. Role for mechanotransduction in macrophage and dendritic cell immunobiology. Results Probl Cell Differ. 2017;62:209–42.

Pugin J, Dunn I, Jolliet P, Tassaux D, Magnenat JL, Nicod LP, Chevrolet JC. Activation of human macrophages by mechanical ventilation in vitro. Am J Phys. 1998;275:L1040–50.

Fujishiro T, Nishikawa T, Shibanuma N, Akisue T, Takikawa S, Yamamoto T, Yoshiya S, Kurosaka M. Effect of cyclic mechanical stretch and titanium particles on prostaglandin E2 production by human macrophages in vitro. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2004;68:531–6.

Wehner S, Buchholz BM, Schuchtrup S, Rocke A, Schaefer N, Lysson M, Hirner A, Kalff JC. Mechanical strain and TLR4 synergistically induce cell-specific inflammatory gene expression in intestinal smooth muscle cells and peritoneal macrophages. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2010;299:G1187–97.

Lang CJ, Barnett EK, Doyle IR. Stretch and CO2 modulate the inflammatory response of alveolar macrophages through independent changes in metabolic activity. Cytokine. 2006;33:346–51.

Lee HG, Hsu A, Goto H, Nizami S, Lee JH, Cadet ER, Tang P, Shaji R, Chandhanayinyong C, Kweon SH, Oh DS, Tawfeek H, Lee FY. Aggravation of inflammatory response by costimulation with titanium particles and mechanical perturbations in osteoblast- and macrophage-like cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2013;304:C431–9.

Yang JH, Sakamoto H, Xu EC, Lee RT. Biomechanical regulation of human monocyte/macrophage molecular function. Am J Pathol. 2000;156:1797–804.

Kao CT, Huang TH, Fang HY, Chen YW, Chien CF, Shie MY, Yeh CH. Tensile force on human macrophage cells promotes osteoclastogenesis through receptor activator of nuclear factor κB ligand induction. J Bone Miner Metab. 2016;34:406–16.

Suzuki N, Yoshimura Y, Deyama Y, Suzuki K, Kitagawa Y. Mechanical stress directly suppresses osteoclast differentiation in RAW264.7 cells. Int J Mol Med. 2008;21:291–6.

Kameyama S, Yoshimura Y, Kameyama T, Kikuiri T, Matsuno M, Deyama Y, Suzuki K, Iida J. Short-term mechanical stress inhibits osteoclastogenesis via suppression of DC-STAMP in RAW264.7 cells. Int J Mol Med. 2013;31:292–8.

Guo Y, Wang Y, Liu Y, Wang H, Guo C, Zhang X. Effect of the same mechanical loading on osteogenesis and osteoclastogenesis in vitro. Chin J Traumatol. 2015;18:150–6.

Hayakawa T, Yoshimura Y, Kikuiri T, Matsuno M, Hasegawa T, Fukushima K, Shibata K, Deyama Y, Suzuki K, Iida J. Optimal compressive force accelerates osteoclastogenesis in RAW264.7 cells. Mol Med Rep. 2015;12:5879–85.

Cho ES, Lee KS, Son YO, Jang YS, Lee SY, Kwak SY, Yang YM, Park SM, Lee JC. Compressive mechanical force augments osteoclastogenesis by bone marrow macrophages through activation of c-Fms-mediated signaling. J Cell Biochem. 2010;111:1260–9.

Ikeda M, Yoshimura Y, Kikuiri T, Matsuno M, Hasegawa T, Fukushima K, Hayakawa T, Minamikawa H, Suzuki K, Iida J. Release from optimal compressive force suppresses osteoclast differentiation. Mol Med Rep. 2016;14:4699–705.

Suzuki R, Nemoto E, Shimauchi H. Cyclic tensile force up-regulates BMP-2 expression through MAP kinase and COX-2/PGE2 signaling pathways in human periodontal ligament cells. Exp Cell Res. 2014;323:232–41.

Graves DT, Cochran D. The contribution of interleukin-1 and tumor necrosis factor to periodontal tissue destruction. J Periodontol. 2003;74:391–401.

Kayal RA. The role of osteoimmunology in periodontal disease. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:639368.

Davis BK, Wen H, Ting JP. The inflammasome NLRs in immunity, inflammation, and associated diseases. Annu Rev Immunol. 2011;29:707–35.

Karasawa T, Takahashi M. The crystal-induced activation of NLRP3 inflammasomes in atherosclerosis. Inflamm Regen. 2017;37:18.

Sharma D, Kanneganti TD. The cell biology of inflammasomes: mechanisms of inflammasome activation and regulation. J Cell Biol. 2016;213:617–29.

Feldman N, Rotter-Maskowitz A, Okun E. DAMPs as mediators of sterile inflammation in aging-related pathologies. Ageing Res Rev. 2015;24:29–39.

Shao BZ, Xu ZQ, Han BZ, Su DF, Liu C. NLRP3 inflammasome and its inhibitors: a review. Front Pharmacol. 2015;6:262.

Jo EK, Kim JK, Shin DM, Sasakawa C. Molecular mechanisms regulating NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Cell Mol Immunol. 2016;13:148–59.

He Y, Hara H, Núñez G. Mechanism and regulation of NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Trends Biochem Sci. 2016;41:1012–21.

Wu J, Yan Z, Schwartz DE, Yu J, Malik AB, Hu G. Activation of NLRP3 inflammasome in alveolar macrophages contributes to mechanical stretch-induced lung inflammation and injury. J Immunol. 2013;190:3590–9.

Stojadinovic O, Minkiewicz J, Sawaya A, Bourne JW, Torzilli P, de Rivero Vaccari JP, Dietrich WD, Keane RW, Tomic-Canic M. Deep tissue injury in development of pressure ulcers: a decrease of inflammasome activation and changes in human skin morphology in response to aging and mechanical load. PLoS One. 2013;8:e69223.

Maruyama K, Sakisaka Y, Suto M, Tada H, Nakamura T, Yamada S, Nemoto E. Cyclic stretch negatively regulates IL-1β secretion through the inhibition of NLRP3 inflammasome activation by attenuating the AMP kinase pathway. Front Physiol. 2018;9:802.

Gombault A, Baron L, Couillin I. ATP release and purinergic signaling in NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Front Immunol. 2012;3:414.

Binderman I, Gadban N, Yaffe A. Extracellular ATP is a key modulator of alveolar bone loss in periodontitis. Arch Oral Biol. 2017;81:131–5.

Franchi L, Muñoz-Planillo R, Núñez G. Sensing and reacting to microbes through the inflammasomes. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:325–32.

Yamamoto Y, Gaynor RB. IkappaB kinases: key regulators of the NF-kappaB pathway. Trends Biochem Sci. 2004;29:72–9.

Li Q, Verma IM. NF-kappaB regulation in the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:725–34.

Bauernfeind FG, Horvath G, Stutz A, Alnemri ES, MacDonald K, Speert D, Fernandes-Alnemri T, Wu J, Monks BG, Fitzgerald KA, Hornung V, Latz E. Cutting edge: NF-kappaB activating pattern recognition and cytokine receptors license NLRP3 inflammasome activation by regulating NLRP3 expression. J Immunol. 2009;183:787–91.

Inoki K, Kim J, Guan KL. AMPK and mTOR in cellular energy homeostasis and drug targets. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2012;52:381–400.

O'Neill LA, Hardie DG. Metabolism of inflammation limited by AMPK and pseudo-starvation. Nature. 2013;493:346–55.

Cordero MD, Williams MR, Ryffel B. AMP-activated protein kinase regulation of the NLRP3 inflammasome during aging. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2018;29:8–17.

Zha QB, Wei HX, Li CG, Liang YD, Xu LH, Bai WJ, Pan H, He XH, Ouyang DY. ATP-induced inflammasome activation and pyroptosis is regulated by AMP-activated protein kinase in macrophages. Front Immunol. 2016;7:597.

Liang YD, Bai WJ, Li CG, Xu LH, Wei HX, Pan H, He XH, Ouyang DY. Piperine suppresses pyroptosis and interleukin-1β release upon ATP triggering and bacterial infection. Front Pharmacol. 2016;7:390.

Peng X, Yang T, Liu G, Liu H, Peng Y, He L. Piperine ameliorated lupus nephritis by targeting AMPK-mediated activation of NLRP3 inflammasome. Int Immunopharmacol. 2018;65:448–57.

Harun-Or-Rashid M, Inman DM. Reduced AMPK activation and increased HCAR activation drive anti-inflammatory response and neuroprotection in glaucoma. J Neuroinflammation. 2018;15:313.

Atherton PJ, Szewczyk NJ, Selby A, Rankin D, Hillier K, Smith K, Rennie MJ, Loughna PT. Cyclic stretch reduces myofibrillar protein synthesis despite increases in FAK and anabolic signalling in L6 cells. J Physiol. 2009;587:3719–27.

Nakai N, Kawano F, Nakata K. Mechanical stretch activates mammalian target of rapamycin and AMP-activated protein kinase pathways in skeletal muscle cells. Mol Cell Biochem. 2015;406:285–92.

Kunanusornchai W, Muanprasat C, Chatsudthipong V. Adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase activation and suppression of inflammatory response by cell stretching in rabbit synovial fibroblasts. Mol Cell Biochem. 2016;423:175–85.

Ballotta V, Driessen-Mol A, Bouten CV, Baaijens FP. Strain-dependent modulation of macrophage polarization within scaffolds. Biomaterials. 2014;35:4919–28.

Matheson LA, Fairbank NJ, Maksym GN, Paul Santerre J, Labow RS. Characterization of the Flexcell™ Uniflex™ cyclic strain culture system with U937 macrophage-like cells. Biomaterials. 2006;27:226–33.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to our colleagues and laboratory members for their helpful discussions and experimental assistance. We also thank D. Mrozek (Medical English Editing Service, Kyoto, Japan) for editing the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (16H05553) and a Grant-in-Aid for Challenging Exploratory Research (25670805) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KM, EN, and YS drafted the manuscript. EN gave the final approval of the article. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

The experimental procedures were approved by the Ethical Review Board of Tohoku University Graduate School of Dentistry approval number 26–27.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Maruyama, K., Nemoto, E. & Yamada, S. Mechanical regulation of macrophage function - cyclic tensile force inhibits NLRP3 inflammasome-dependent IL-1β secretion in murine macrophages. Inflamm Regener 39, 3 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41232-019-0092-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41232-019-0092-2