Abstract

A subadult leatherback turtle was documented in the Gulf of Goubet (Djibouti) during a research expedition. This sighting confirms for the first time previous anecdotal observations of the occurrence of the leatherback turtle, Dermochelys coriacea (Vandelli, 1761), in Djibouti waters. Coupled with observations from fishers, this finding underlines the urgent need to carry out research programs to evaluate the species habitat use within Djibouti waters, and to review the species distribution in the Gulf of Aden. Although marine turtles are protected in Djibouti, illegal harvest and entanglement in fishing gear pose a threat to their survival, and conservation measures should be implemented.

Similar content being viewed by others

The leatherback turtle, Dermochelys coriacea (Vandelli, 1761), is the most pelagic and widely distributed marine turtle species (Marquez 1990), and is listed as ‘Vulnerable’ on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species with a decreasing population (Wallace et al. 2013). Distribution of both juveniles and adults likely reflects the spatiotemporal abundance of zooplanktonic prey, and leatherback turtles have been observed aggregating in areas where jellyfish blooms occur (James et al. 2005). D. coriacea is globally distributed from tropical to subpolar waters, but the Gulf of Aden is not contained within the known geographic range of the Indian Ocean subpopulation (Wallace et al. 2013). Although suitable prey is seasonally abundant, the species has only rarely been documented from the Gulf of Aden, primarily in Yemeni waters (Hamann et al. 2006; Pilcher and Saad 2006). Anecdotal reports from fishers have reported sightings of leatherback turtles in Djibouti (Hamann et al. 2006), however none of these were accompanied by reliable documentation.

Within the Gulf of Aden, Djibouti is an important hotspot for marine biodiversity due to the confluence of warm waters from the Red Sea and cold water from the Somali and Arabian regions that creates a unique marine ecosystem. The area is home to several endangered and poorly known species, such as the whale shark, Rhincodon typus (Rowat et al. 2007; Boldrocchi et al. 2020), and the Indian Ocean humpback dolphin, Sousa plumbea (Braulik et al. 2017). The Djibouti marine ecosystem also hosts several threated marine turtle species, including the green, Chelonia mydas; hawksbill, Eretmochelys imbricata; and loggerhead Caretta caretta (PERSGA 2004), although no research currently takes place on any these species. Given the lack of knowledge on marine turtle biodiversity in Djibouti, and the wider Gulf of Aden, this note provides additional information regarding the distribution of the leatherback turtle in a poorly studied region of the world.

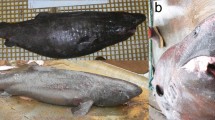

During a research expedition, on 02 December 2019, a leatherback specimen was documented for the first time in the Djibouti waters of the Gulf of Goubet (the far western region of the Gulf of Aden) (Fig. 1a). The turtle was spotted on the surface near the ‘La Faille’ dive site (11°34′45.1″N 42°31′25.2″E), and at < 1 m estimated curved carapace length it was judged to be a sub-adult (Stewart et al. 2007) (Fig. 1b). This sighting confirms at minimum the occasional presence of this species in Djibouti.

Globally, satellite telemetry suggests that leatherback movements are directed to areas that show seasonally persistent densities of prey (Ferraroli et al. 2004; Hays et al. 2004; Witt et al. 2007). In Djibouti, the southwest monsoon induces eastward movement of surface water and enhances upwelling of nutrient rich waters in the Gulf Goubet (Omar et al. 2016), with a consequent increase of the zooplankton population in October–December (Boldrocchi et al. 2020). The leatherback sighting described here occurred during the upwelling season, when the Djibouti marine ecosystem experiences a peak in zooplankton biomass (Boldrocchi et al. 2020). The southwest monsoon upwelling is notably enhanced within the Gulf of Goubet, which not only retains more nutrients than other bays but also blooms of comb jellies, consistent with the soft-body prey preferred by D. coriacea (Boldrocchi et al. 2020). This increase in prey availability may represent an important driver for the leatherback presence in the neritic waters of Djibouti during this time of the year.

At present, information remains too limited to determine whether Djibouti is a permanent foraging site or simply a transit area for leatherback turtles. However, our observation, with reports from fishers in Djibouti, Yemen (Saad 2002; Pilcher and Saad 2006) and Somalia (Van de Elst 2006), suggest that the Gulf of Aden may be more important habitat for D. coriacea than previously recognized. Although national laws protect marine turtles in Djibouti, illegal harvest for meat and ornamental carapace collection is still widespread (Hamann et al. 2006), and other anthropogenic threats, such as entanglement in fishing gear, cause additional mortality (PERSGA 2004). Considering the minimal regulatory oversight in this region, and the threats that undermine marine turtle conservation, population monitoring programs should be carried out.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable

References

Boldrocchi G, Moussa O, Azzola A, Bettinetti R. The ecology of the whale shark in Djibouti. Aquat Ecol. 2020:1–17.

Braulik, G.T., Findlay, K., Cerchio, S., Baldwin, R., & Perrin, W.. Sousa plumbea. The IUCN red list of threatened species 2017: e.T82031633A82031644. 2017. https://doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-3.RLTS.T82031633A82031644.en. Downloaded on 06 June 2020.

Ferraroli S, Georges JY, Gaspar P, Le Maho Y. Where leatherback turtles meet fisheries. Nature. 2004;429(6991):521–2.

Hamann M, Limpus C, Hughes G, Mortimer J, Pilcher N. Assessment of the conservation status of the leatherback turtle in the Indian Ocean and South East Asia, including consideration of the impacts of the December 2004 tsunami on turtles and turtle habitats. Bangkok: IOSEA Marine Turtle MoU Secretariat; 2006.

Hays GC, Houghton JD, Myers AE. Pan-Atlantic leatherback turtle movements. Nature. 2004;429(6991):522.

James MC, Myers RA, Ottensmeyer CA. Behaviour of leatherback marine turtles, Dermochelys coriacea, during the migratory cycle. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci. 2005;272(1572):1547–55.

Marquez R. Sea turtles of the world. An annotated and illustrated catalogue of sea turtle species known to date. FAO Species Catalogue FAO Fisheries Synopsis. 1990;11(125):81.

Omar YM, Memery L, Carton X, Daher A, Duvielbourg E. Effects of monsoon winds and topographical features on the vertical thermohaline and biogeochemical structure in the Gulf of Tadjourah (Djibouti). Open J Mar Sci. 2016;6(03):440–55.

PERSGA. Regional action plan for the conservation of marine turtles and their habitats in the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden. Jeddah: PERSGA; 2004.

Pilcher, N.J., & Saad, M.. Status of leatherback turtles in Yemen. Assessment of the conservation status of the leatherback turtle in the Indian Ocean and South-East Asia IOSEA Species Assessment, 1. 2006.

Rowat D, Meekan MG, Engelhardt U, Pardigon B, Vely M. Aggregations of juvenile whale sharks (Rhincodon typus) in the Gulf of Tadjoura, Djibouti. Environ Biol Fish. 2007;80(4):465–72.

Saad MA. Status of marine turtles in Yemen: survey report. PERSGA/SAP technical document 1981. In: Summary review of the Red Sea commercial fisheries, catches and stock assessments. FAO/UNDPRAB/77/008/19′. (Eds MJ Sanders and SM Kedidi). Jeddah; 2002. p. 12.

Stewart K, Johnson C, Godfrey MH. The minimum size of leatherbacks at reproductive maturity, with a review of sizes for nesting females from the Indian, Atlantic and Pacific Ocean basins. J Herpetol. 2007;17(2):123–8.

Van de Elst R. Status of leatherback turtles in Somalia. Assessment of the conservation status of the leatherback turtle in the Indian Ocean and South-East Asia. IOSEA Species Assess. 2006;1:122–4.

Wallace, B.P., Tiwari, M. & Girondot, M.. Dermochelys coriacea. The IUCN red list of threatened species 2013: e.T6494A43526147. 2013. https://doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2013-2.RLTS.T6494A43526147.en. Downloaded on 06 June 2020.

Witt MJ, Broderick AC, Johns DJ, Martin C, Penrose R, Hoogmoed MS, Godley BJ. Prey landscapes help identify potential foraging habitats for leatherback turtles in the NE Atlantic. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 2007;337:231–43.

Funding

No funding was provided for this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

GB, JVS and DPR made the observation described here, interpreted the data and generated the manuscript. DPR took the photograph in Fig. 1b. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Boldrocchi, G., Schmidt, J.V. & Robinson, D.P. First documented record of the leatherback turtle (Dermochelys coriacea) from Djibouti waters. Mar Biodivers Rec 14, 3 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41200-021-00200-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41200-021-00200-0