Abstract

Background

The alien cup-coral Tubastraea spp. has been increasingly reported in the Southwestern Atlantic since the 1980s. More recently it was observed on the East coast of Brazil, the area with the highest biodiversity in the Southwest Atlantic. In the present study, we report the actual distribution of Tubastraea tagusensis and Tubastraea coccinea around Todos os Santos Bay (TSB), an important system in the Southwest Atlantic coast.

Results

We mapped the geographic expansion of Tubastraea tagusensis and Tubastraea coccinea at 11 sites in estuarine and 2 in reef systems at TSB.

Conclusions

The findings from our study will contribute to monitor alien expansion and implement management actions to control these invasions on the Brazilian coast.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The native Indo-Pacific cup coral, Tubastraea Lesson, 1829 (Scleractinia: Dendrophylliidae) is one the most widely distributed azooxanthellate coral genera in the world and its non-native range extends to the Caribbean Sea, the Gulf of Mexico and Western Atlantic (Cairns, 2000; Castro & Pires, 2001; Ferreira, 2003; de Paula & Creed, 2004; Fenner & Banks, 2004; Mantelatto et al., 2011; Sampaio et al., 2012). Two species of Tubastraea were introduced in the Southwest Atlantic (Tubastraea tagusensis Wells, 1982 and Tubastraea coccinea Lesson, 1829) where they are considered to be alien and invasive species, mainly because of their high fecundity (de Paula et al., 2014), rapid linear skeletal growth (Wellington & Trench 1985), allelochemical defenses (Lages et al., 2010a, b) and competitive aggressiveness (dos Santos et al., 2013; Miranda et al., 2016).

The alien cup corals (T. tagusensis and T. coccinea) were reported for first time in the Southwest Atlantic in 1980s on oil and gas platforms in the Campos Basin, Southeast of Brazil (Castro & Pires, 2001). Subsequently, these alien coral spread rapidly along the Southeastern (Ferreira, 2003; de Paula & Creed, 2004; da Silva et al., 2014) and Southern (Capel, 2012) coast of Brazil, changing the native benthic community structure on rocky shores (Lages et al., 2011). However, several researchers have showed great concern with the invasion of this alien coral species on the east tropical coast of Brazil (dos Santos et al., 2013; Costa et al., 2014), where the most important coral reefs and the highest marine biodiversity in the Southwest Atlantic can be found (Leão et al., 2003).

Recently, T. coccinea and T. tagusensis were reported in Todos os Santos Bay (TSB), Bahia state in Eastern Brazil (Sampaio et al., 2012). This bay is considered a priority for conservation due to its high levels of coral endemism and to the great diversity of natural systems (Leão et al., 2003; Barros et al. 2012a, b; Vila-Nova et al., 2014; Cruz et al., 2015). Previous studies in TSB have shown that this alien coral can modify the benthic assemblage structure on a coral reef site (Miranda et al., 2016). Therefore, an expansion of Tubastraea species on others reefs or even to other habitats (e.g., estuaries) can potentially modify biodiversity and eventually alters dynamics and functioning of the natural systems in TSB.

To date, no studies have evaluated the geographical distribution and potential expansion of this alien around TSB. In the present study, we report the actual distribution of Tubastraea tagusensis and Tubastraea coccinea around TSB, an important system in the Southwest Atlantic coast. We reveal thirteen new records on the estuarine and reef systems in TSB and discuss how these findings will contribute to the future monitoring and management of this alien coral.

Material and methods

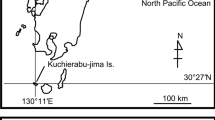

An extensive SCUBA diving survey was performed on 50 sites of the reef and estuarine systems around TSB between January 2011 and January 2015, to record the presence of the alien species Tubastraea tagusensis and Tubastraea coccinea (Fig. 1). The reef systems were mainly located at the entrance to the bay, in its central, northeastern, and exterior parts, and in a large estuarine system in the northwestern section of TSB (Paraguaçu estuary, Fig. 1a).

At each site, three SCUBA divers swam near the consolidated substrate in opposite directions, checking the presence of each species of Tubastraea. Each diver conducted three 10 m transects, spending about 5 min per each transect. The alien species were visually identified, photographed and recorded on PVC plates. The two species (T. tagusensis and T. coccinea) are morphologically different and easily distinguished from other native coral species (de Paula & Creed, 2004).

Results

Our survey showed that the alien species Tubastraea tagusensis and Tubastraea coccinea were present in 18 sites and absent in 32 sites around TSB (Figs. 1 and 2). Among the 18 invaded sites, we identified 13 new reports and confirm the establishment of the alien coral on 5 sites previously reported. Table 1 shows description of invaded sites listed by invasion chronological order.

The alien coral species were found on 12 sites in Paraguaçu estuary and on 6 different reef sites of TSB mostly in cryptic habitats with vertical and/or negative inclinations, low light incidence, and depth between 0.5 to 21 m. In the Paraguaçu estuary, the invasive species were also observed on intertidal areas where, in low tides, it was exposed to desiccation (e.g., Fig. 2c). Several invaded sites of consolidated substrata were observed in Paraguaçu estuary, mainly on artificial substrates (piers, n = 10 and oil platforms, n = 1) as well as natural rocky reefs (n = 2). In the reef systems, these species were observed mainly on artificial structures (seawall, nautical signs, pier and shipwreck) but also on natural coral reefs (Table 1).

Several natural coral reefs (n = 22) around TSB, still not invaded by Tubastraea species, were reported on Fig. 1 for future monitoring.

Discussion

Our results demonstrated an expansion of Tubastraea tagusensis and Tubastraea coccinea inside TSB, such that they are now distributed in over 18 sites in the estuary and on reef systems, following their first record in 2008 (Sampaio et al., 2012). Possible explanations of the continuous invasion of these species are related to several biological characteristics of this invader including their reproductive strategies (e.g. high oocyte production, precocious reproduction age, short embryo incubation time and hermaphroditism; de Paula et al., 2014) in addition to its ability to successfully colonize different substrates and habitats (Creed & de Paula, 2007). During spawning peaks, these species can release a large number of larvae (de Paula et al., 2014) that are dispersed by currents and the planulae are highly buoyant, swimming actively through ciliary movements (Mizrahi, 2008). Therefore, several observations of this alien coral were made not only on natural rocky and coral reefs but also on artificial piers, oil platforms and seawalls in TSB.

Surprisingly, the number of invaded sites was relatively high in Paraguaçu estuary, even though the occurrence of the alien cup coral in other estuarine systems has rarely been reported (Cairns, 2000; Fenner & Banks, 2004; de Paula & Creed, 2005). Estuaries have highly variable salinity levels (Mclusky, 1993; Mclusky & Elliott, 2008) that can limit survival of many coral reef species. Moreira et al. (2014) experimentally showed high mortality rates of T. tagusensis and T. coccinea when exposed to low salinity (i.e., 0, 5, 10 practical salinity units). However, the Tubastraea invasion in the Paraguaçu estuary may have occurred due to the predominance of marine salinity levels (Genz et al., 2008; Reis-Filho et al., 2010; Genz & Lessa, 2015). This condition is likely to be associated with the building of the Pedra do Cavalo Dam in 1985 and Pedra do Cavalo Hydroeletric Power Plant in 2005 on the upper estuary (Fig. 1), which altered the hydrological regime by reducing freshwater flow (Genz et al., 2008). Furthermore, the frequent oil platforms anchorage at São Roque do Paraguaçu shipyard in the lower estuary (Fig. 1a), may explain the high number of invaded sites in this area. Oil platforms are one of the main vectors for alien cup coral introductions around the world (J.C. Creed et al., unpubl. data). In fact, one introduction was previously reported at the Paraguaçu estuary on April 7th 2014 (J.C. Creed et al., unpubl. data); but has not been investigated. Finally, the building of the Enseada do Paraguaçu shipyard in 2014 also increased the chances of alien cup coral establishment in this estuary.

The high number of invaded sites on Paraguaçu estuary shows the success of the alien coral colonization on consolidated substrate (natural and artificial). Several studies have shown that colonization of Tubastraea species on invaded areas may be facilitated by production of allelochemicals (secondary metabolites, see Lages et al., 2010a, b) with anti-fouling and anti-predation properties capable of causing damage in native competitors (Lages et al., 2012). Thus, Tubastraea species once established at Paraguaçu estuary could reduce native species abundance (e.g., oysters and barnacles) altering the benthic structure assemblage on consolidated substrate (Lages et al., 2011; Mantelatto & Creed, 2014). The suspension-feeding native oyster (e.g., Crassostrea spp.) may play a valuable role on estuarine productivity by filtering particulate material from water column and then depositing on the bottom, which are available to the benthic deposit feeders (e.g., polychaetes and molluscs) (Mclusky & Elliott, 2008). In fact, benthic macroinfauna in soft sediments of Paraguaçú estuary is a diverse and relatively preserved assemblage (e.g., Barros et al. 2012a, b; Barros et al., 2014). Therefore, changes in these assemblages could profoundly affect ecosystem processes.

Invaded sites were also found on the reef system including one coral reef site inside the bay (Pedra da Pizza, see Fig. 1 and Table 1). This was the second invaded coral reef site in TSB, after the first location was reported in 2011 outside the bay (Cascos Reef, see Sampaio et al., 2012). Coral reefs are well known as important systems that harbor high diversity in some areas and provide several resources for associated organisms (e.g., Moberg & Folke, 1999; Costanza et al., 2014). TSB coral reefs concentrate relatively high species richness and endemism for Brazil (Leão et al., 2003). Previous studies showed that the presence of the alien coral on Cascos Reef altered the native benthic assemblage structure likely by increasing the mortality of some native coral species through efficient competition (Miranda et al., 2016). Consequently, the expansion of the alien coral on TSB’ coral reefs may reduce native coral cover and cause changes in the functional benthic group dominance (Cruz et al. 2014) from hermatypic to ahermatypic coral, altering coral reef functioning. Coral reefs are highly dependent on hermatypic corals (e.g., branching, tabular and massive forms) which build complex physical structures, creating several microhabitats which favor high biodiversity (Graham & Nash, 2012; Leal et al., 2013; Rogers et al., 2014). Thus, the change from hermatypic to ahermatipic coral dominance could impact the richness and abundance of associated species.

Tubastraea invasion might affect not only benthic assemblages as pointed out above, but also fish assemblages in TSB. For instance, changes in habitat complexity, reduction of hermatypic coral and algae cover and abundance of invertebrates associated with different habitats (coral, rocky reefs, mangroves) can lead to shifts in fish foraging microhabitat choices and flight responses (e.g., Nunes et al., 2013; Nunes et al., 2015). However, these effects must be formally searched for.

Conclusions

Here we presented a detailed distribution and evidence of expansion of the cup corals (T. coccinea and T. tagusensis) in the TSB that will contribute to the establishment of an important baseline for the long-term monitoring of the invasion of these species in the bay. Based on the results of the present study, we urgently recommend the monitoring of all of the study sites and the discussion and implementation of management actions at the invaded sites to control the alien coral expansion. The reduction of propagule pressure is the main recommendation to control invasion success (Johnston et al., 2009). Currently, manual control (i.e., colony removal by divers) is the only viable action to reduce propagule pressure of Tubastraea species in Brazil (da Silva et al., 2014). It was first implemented on invaded rocky shores at Ilha Grande Bay (Rio de Janeiro state, see da Silva et al., 2014) and on coral reefs at TSB it has been carefully conducted on a small scale. Nevertheless, as these species have high reproductive capacity (de Paula et al., 2014), we suggest that studies must be carefully conducted (i) to evaluate the efficiency of manual removal for reduction of alien coral populations and (ii) to develop new methods for control.

Currently, the Paraguaçu estuary is the main source of alien coral in TSB and we agree with recommendations that all oil platforms should be cleaned more effectively (Costa et al., 2014), using freshwater (low salinity, see Moreira et al., 2014) before entering TSB.

Abbreviation

TSB, Todos os Santos Bay

References

Barros F, Costa PC, Cruz I, Mariano DLS, Miranda RJ. Hábitats Bentônicos na Baía de Todos os Santos. Revista Virtual de Química. 2012a;4(5):551–65.

Barros F, Carvalho GC, Costa Y, Hatje V. Subtidal benthic macroinfaunal assemblages in tropical estuaries: Generality amongst highly variable gradients. Mar Environ Res. 2012b;81:43–52.

Barros F, Blanchet H, Hammerstrom K, Sauriau PG, Oliver J. A framework for investigating general patterns of benthic β-diversity along estuaries. Estuar Coast Shelf Sci. 2014;149:223–31.

Cairns SD. Revision shallow-water azooxanthellate scleractinia western Atlantic, Foundation for Scientific Research in the Caribbean Region: Studies of the Natural History of the Caribbean Region. 143rd ed. 2000.

Capel KCC. Scleractinia (Cnidaria: Anthozoa) da Reserva Biológica Marinha do Arvoredo (SC), com ênfase na estrutura espaço-temporal da formação mais meridional de corais recifais no Oceano Atlântico, Master thesis. Florianópolis, Brazil: Federal University of Santa Catarina; 2012.

Castro CB, Pires DO. Brazilian coral reefs: what we already know and what is still missing. Bull Mar Sci. 2001;69:357–71.

Costa TJF, Pinheiro HT, Teixeira JB, Mazzei EF, Bueno L, Hora MSC, Joyeux JC, Carvalho-Filho A, Amado-Filho G, Sampaio CLS, Rocha LA. Expansion of an invasive coral species over Abrolhos Bank, Southwestern Atlantic. Mar Pollut Bull. 2014;85:252–3.

Costanza R, de Groot R, Sutton P, van der Ploeg S, Anderson SJ, Kubiszewski I, Farber S, Turner RK. Changes in the global value of ecosystem services. Glob Environ Chang. 2014;26:152–8.

Creed JC, De Paula AF. Substratum preference during recruitment of two invasive alien corals onto shallow-subtidal tropical rocky shores. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 2007;330:101–11.

Cruz ICS, Kikuchi RPK, Creed JC. Improving the construction of functional models of alternative persistent states in coral reefs using insights from ongoing research programs: A discussion paper. Mar Environ Res. 2014;97:1–9.

Cruz ICS, Kikuchi RPK, Leão ZMAN, Done TJ. Reef quality criteria for marine reserve selection: an example from eastern Brazil. Aquat Conserv Mar Freshwat Ecosyst. 2015;25:223–34.

da Silva AG, de Paula AF, Fleury BG, Creed JC. Eleven years of range expansion of two invasive corals (Tubastraea coccinea and Tubastraea tagusensis) through the southwest Atlantic (Brazil). Estuar Coast Shelf Sci. 2014;141:9–16.

de Paula AF, Creed JC. Two species of the coral Tubastraea (cnidaria, scleractinia) in Brazil: a case of accidental introduction. Bull Mar Sci. 2004;74:175–83.

de Paula AF, Creed JC. Spatial distribution and abundance of nonindigenous coral genus Tubastraea (Cnidaria, Scleractinia) around Ilha Grande, Brazil. Braz J Biol. 2005;65:661–73.

de Paula AF, Pires DO, Creed JC. Reproductive strategies of two invasive sun corals (Tubastraea spp.) in the southwestern Atlantic. J Mar Biol Assoc U K. 2014;94(3):481–92.

dos Santos LAH, Ribeiro FV, Creed JC. Antagonism between invasive pest corals Tubastraea spp. and the native reef-builder Mussismilia hispida in the southwest Atlantic. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol. 2013;449:69–76.

Fenner D, Banks K. Orange Cup Coral Tubastraea coccinea invades Florida and the Flower Garden Banks, Northwestern Gulf of Mexico. Coral Reefs. 2004;23:505–7.

Ferreira CEL. Non-indigenous corals at marginal sites. Coral Reefs. 2003;22:498.

Genz F, Lessa GC, Cirano M. Vazão mínima para Estuários: Um Estudo de Caso no Rio Paraguaçu/BA. Rev Bras Recur Hidr. 2008;13:73–82.

Genz F, Lessa GC. Twenty-six years of uneven changes in low flows due to different uses and operation of a large dam in a semiarid river. Rev Bras Recur Hidr. 2015;20(2):523–32.

Graham NAJ, Nash KL. The importance of structural complexity in coral reef ecosystems. Coral Reefs. 2012;32:315–26. doi:10.1007/s00338-012-0984-y.

Johnston E, Piola R, Clark G. The Role of Propagule Pressure in Invasion Success. In: Rilov G, Crooks J, editors. Biological Invasions in Marine Ecosystems. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer; 2009. p. 133–51.

Lages BG, Fleury BG, Pinto AC, Creed JC. Chemical defenses against generalist fish predators and fouling organisms in two invasive ahermatypic corals in the genus Tubastraea. Mar Ecol. 2010a;31:473–82.

Lages BG, Fleury BG, Rezende CM, Pinto AC, Creed JC. Chemical composition and release in situ due to injury of the invasive coral Tubastraea (Cnidaria, Sclaractinia). Braz J Oceanogr. 2010b;58:47–56.

Lages BG, Fleury BG, Menegola C, Creed JC. Change in tropical rocky shore communities due to an alien coral invasion. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 2011;438:85–96.

Lages BG, Fleury BG, Hovell AMC, Rezende CM, Pinto AC, Creed JC. Proximity to competitors changes secondary metabolites of nonindigenous cup corals, Tubastraea spp., in the southwest Atlantic. Mar Biol. 2012;159:1551–9.

Leal ICS, Pereira PHC, Araújo ME. Coral reef fish association and behaviour on the fire coral Millepora spp. in north-east Brazil. J Mar Biol Assoc U K. 2013;93(6):1703–11. doi:10.1017/S0025315413000234.

Leão ZMAN, Kikuchi RKP, Testa V. Corals and coral reefs of Brazil. In: Cortés J, editor. Latin America Corals Reefs. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2003. p. 9–52.

Mantelatto MC, Creed JC. Non-indigenous sun corals invade mussel beds in Brazil. Marine Biodiversity. 2014;45(4):605-6.

Mantelatto MC, Creed JC, Mourão GG, Migotto AE, Lindner A. Range expansion of the invasive corals Tubastraea coccinea and Tubastraea tagusensis in the Southwest Atlantic. Coral Reefs. 2011;30:397.

Mclusky DS. Marine and Estuarine Gradients – An Overview. Neth J Aquat Ecol. 1993;27:489–93.

Mclusky DS, Elliott M. The Estuarine Ecosystem: ecology, threats and management. 3rd ed. Oxford: University Press; 2008.

Miranda RJ, Porto L, Cruz ICS, Barros F. Coral invasor Tubastraea spp. em recifes de corais e substratos artificiais na Baía de Todos os Santos (BA). Congresso Brasileiro de Oceanografia, Associação Brasileira de Oceanografia, Rio de Janeiro, 13-16 November 2012. 2012. pp. 1527-32.

Miranda RJ, Cruz ICS, Barros F. Effects of the alien coral Tubastraea tagusensis on native coral assemblages in a southwestern Atlantic coral reef. Mar Biol. 2016;163:45. doi:10.1007/s00227-016-2819-9.

Mizrahi D. Influência da temperatura e luminosidade na distribuição da espécie invasora Tubastraea coccínea na região de ressurgência de Arraial do Cabo – RJ, Master thesis. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: Federal University of Rio de Janeiro; 2008.

Moberg F, Folke C. Ecological goods and services of coral reef ecosystems. Ecol Econ. 1999;29:215–33.

Moreira PL, Ribeiro FV, Creed JC. Control of invasive marine invertebrates: an experimental evaluation of the use of low salinity for managing pest corals (Tubastraea spp.). Biofouling. 2014. doi:10.1080/08927014.2014.906583.

Nunes JACC, Sampaio CLS, Barros F. How wave exposure, group size and habitat complexity influence foraging and population densities in fishes of the genus Halichoeres (Perciformes: Labridae) on tropical rocky shores. Mar Biol. 2013;160:2383–94. doi:10.1007/s00227-013-2233-5.

Nunes JACC, Sampaio CLS, Barros F. The influence of structural complexity and reef habitat types on flight initiation distance and escape behaviors in labrid fishes. Mar Biol. 2015;162:493–9. doi:10.1007/s00227-014-2578-4.

Reis-Filho JA, Nunes JACC, Ferreira A. Estuarine ichthyofauna of the Paraguaçu River, Todos os Santos Bay, Bahia, Brazil. Biota Neotropica. 2010;10(4):301–12.

Rogers A, Blanchard JL, Mumby PJ. Vulnerability of Coral Reef Fisheries to a Loss of Structural Complexity. Curr Biol. 2014;24:1000–5. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2014.03.026.

Sampaio CLS, Miranda RJ, Maia-Nogueira R, Nunes JACC. New occurrences of the nonindigenous orange cup corals Tubastraea coccinea and T. tagusensis (Scleractinia: Dendrophylliidae) in Southwestern Atlantic. Check List. 2012;8:2–4.

Vila-Nova DA, Ferreira CEL, Barbosa FG, Floeter SR. Reef fish hotspots as surrogates for marine conservation in the Brazilian coast. Ocean Coast Manag. 2014;102:88–93.

Wellington GM, Trench RK. Persistence and coexistence of a nonsymbiotic coral in open reef environments. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1985;82:2432–6.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Non-Governmental Organization Pró-Mar, Research Group on Coral Reefs and Global Climate Change, J.A. Reis-Filho, I.C.S. Cruz, I.F. Buda Andrade, Z. Bacafú, R.D. Villegas, J.C. Frood, E.M. Chaves, M. Loiola, T. Albuquerque, G.C. Lessa and J.C. Creed for field assistance. A special thanks to Z. Pescador, R.A. Oliveira, C.L.S. Sampaio, B.P. Ferreira and Z.M.A.N. Leão for their valuable suggestions. RJM was supported by Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior and FB was supported by Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico and Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado da Bahia. We also thank The Rufford Foundation (Small Grant n° 13119-1, Projeto Corais da Baía) for essencial financial support.

Authors’ contributions

Collected the data: RJM. Prepared the map: RJM FLL YC. Wrote the paper: RJM YC FLL JACCN FB. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Miranda, R.J., Costa, Y., Lorders, F.L. et al. New records of the alien cup-corals (Tubastraea spp.) within estuarine and reef systems in Todos os Santos Bay, Southwestern Atlantic. Mar Biodivers Rec 9, 35 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41200-016-0053-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41200-016-0053-2