Abstract

Background

Many authors choose to work with professional medical writers when reporting the results of clinical trials. We conducted a systematic review to examine the relationship between professional medical writing support (PMWS) and the quality, ethics and timeliness of publications reporting clinical trials.

Methods

Using terms related to ‘medical writer’ and ‘observational study’, we searched MEDLINE and Embase (no date limits), as well as abstracts and posters from meetings of the International Society for Medical Publication Professionals (ISMPP; 2014–2018). We also hand-searched the journals Medical Writing and The Write Stuff (2014–2018) and the bibliographies of studies identified in the electronic searches. We screened the results to identify studies that compared the quality, ethics and timeliness of clinical trial publications written with and without declared PMWS.

Results

Our searches identified 97 potentially relevant studies, of which 89 were excluded during screening and full paper review. The remaining eight studies compared 849 publications with PMWS with 2073 articles developed without such support. In these eight studies, PMWS was shown to be associated with increased adherence to Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines (in 3/3 studies in which this was assessed), publication in journals with an impact factor (one study), a higher quality of written English (one study), and a lower likelihood of reporting non-pre-specified outcomes (one study). PMWS was not associated with increased adherence to CONSORT for Abstracts guidelines (one study) or with the impact of published articles (mean number of citations per year, mean number of article views per year and Altmetric score; one study). In studies that assessed timeliness of publication, PMWS was associated with a reduced time from last patient visit in clinical trials to primary publication (one study), whereas time from submission to acceptance showed inconsistent results (two studies).

Conclusions

This systematic review of eight observational studies suggests that PMWS is positively associated with measures of overall quality of reporting of clinical trials and may improve the timeliness of publication.

Video abstract. (MP4 161000 kb)

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Timely and complete reporting of the results of clinical trials is an ethical imperative [1]; it helps to efficiently disseminate research findings and eliminate duplicative effort thereby reducing waste in research funding [2], enables researchers to develop more up-to-date study hypotheses and allows clinicians and patients to judge the benefits or risks of different therapies. Although the pharmaceutical industry has made great strides to address criticism for a perceived lack of transparency in the disclosure of clinical trial results, the quality, ethics and timeliness of clinical trial reporting remain closely scrutinized for both industry-funded and academically funded trials [3,4,5,6,7].

Pharmaceutical companies often offer authors professional medical writing support (PMWS) to assist in the reporting of clinical trial results [8]. International guidelines endorse the acknowledgement of PMWS [9, 10], and the proportion of articles in the medical literature with such an acknowledgement is 5–18% [8, 11, 12]. We conducted a systematic review to identify and analyse published studies that investigated the association between PMWS and the quality, ethics and timeliness of clinical trial reporting.

Methods

Systematic literature search

Published studies relating to medical writing were identified through a systematic literature review. Cochrane, Embase, MEDLINE In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations, and MEDLINE 1946–present were searched on 8 March 2018 via the Ovid platform.

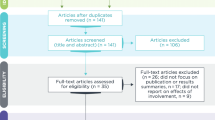

The search strategy comprised terms relating to medical writing, medical publication professional and medical communication and was combined with terms for observational, cross-sectional or epidemiological studies, with no limits on date, language or country in which the research was conducted (Fig. 1).

Supplementary searches

Supplementary searches were conducted of the International Society for Medical Publication Professionals (ISMPP) congress proceedings (which are published as supplementary articles in Current Medical Research Opinion) and the journals Medical Writing and The Write Stuff (which are available via the European Medical Writers Association [EMWA] website) using the terms ‘medical writ*’ and ‘medical publication professional’. A search of the American Medical Writers Association (EMWA) was not part of the search strategy. Supplementary searches were limited to 2014–2018. We contacted the corresponding authors of congress abstracts identified in the supplementary searches to request access to full posters/presentations. The bibliographies of studies identified in the electronic searches were also reviewed to identify additional relevant references.

Study selection and data collection

All identified studies were screened against inclusion and exclusion criteria in accordance with the 2009 Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [13]. For congress abstracts identified in the supplementary searches, full posters were obtained from the ISMPP website or from the authors. Identified congress abstracts were excluded as ‘duplicates’ if a full version of the study had been published. Studies eligible for inclusion were in English and compared the quality, ethics or timeliness of articles reporting clinical trials that had been developed with and without acknowledged PMWS. Studies that did not directly compare clinical trial publications that had been developed with and without PMWS were excluded, as were those that reported outcomes that were unrelated to quality, ethics or timeliness and those that assessed study types other than clinical trials.

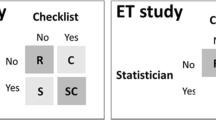

Details of study methodology, study size, main outcome measures, quality and ethics-related outcomes (e.g. adherence to Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials [CONSORT] or CONSORT for Abstracts [CONSORT-A], quality of written English, reporting of non-pre-specified outcomes) and timeliness-related outcomes were extracted from each eligible study. The effect of PMWS was classified as positive, non-significant or negative for each study, based on the results and statistical analyses reported in each publication.

Results

Search results

Our searches identified 75 potentially relevant publications after exclusion of 22 duplicate publications; three publications were identified in bibliographies of identified studies during screening, and 70 were excluded during screening and full paper review (Fig. 1). Of the eight included studies, three were full publications (two in peer-reviewed journals [14, 15], one in a non-peer-reviewed journal [16]), and five were congress abstracts (four poster presentations [17,18,19,20], one oral presentation [21]). Although no date limit was included in the search strategy, only two of the identified studies were published before 2015: one in 2006 [8] and the other in 2010 [16] (Table 1). The eight included studies analysed 849 articles that had been developed with PMWS and 2073 articles developed without.

Quality and ethics of reporting

Of the identified studies comparing articles developed with and without PMWS, three assessed adherence to CONSORT guidelines [15, 16, 20]. Each of these studies, using a different statistical approach to assess adherence, showed that PMWS was associated with increased adherence to CONSORT guidelines (Table 2). Articles developed with PMWS were significantly more likely to report completely at least 50% of the assessed CONSORT items (p < 0.05) [15, 18] and to comply with more CONSORT items than articles without PMWS (p < 0.05) [16]. Similarly, articles with 80–100% compliance with CONSORT items were significantly more likely to have been developed with PMWS than those with less than 80% compliance (p < 0.0001) [20]. Looking at individual CONSORT items, one identified study showed that articles with PMWS were significantly more likely to report all important adverse events or side effects than those without PMWS [16] and another showed that PMWS increased adherence to six of 12 CONSORT items assessed: specification of primary outcome, sample size calculation, type of randomization, publication of a participant flow diagram, provision of dates defining recruitment and follow-up, and details of trial registration [15]. Additionally, in this study, another CONSORT item (who generated the allocation sequence) was only reported in 5/110 articles developed with PMWS and none of the 123 articles without PMWS; thus, a relative risk could not be calculated [15]. One additional study assessed adherence to CONSORT-A and showed that PMWS was not associated with an overall increase in adherence [14]; PMWS was associated with lower levels of adherence with respect to reporting of study setting and higher levels of adherence in relation to disclosure of harms/side effects and funding source in the abstract [14].

Two studies which represented different analyses of the same group of articles looked at other markers of quality in reporting (Table 2) [15, 18]. In these studies, PMWS was positively associated with various measures of reporting quality, including a higher standard of written English (p < 0.01) [15, 18], higher likelihood of publication in a journal with an impact factor (p = 0.001) [18], and higher mean impact factor of the journal accepting the article (p < 0.001) [18]. However, there was no association between PMWS and article-level measures of impact, such as mean number of citations per year (p = 0.11), mean number of article views per year (p = 0.84) and Altmetric score (p = 0.55) (Table 2) [18]. Of the identified studies, one examined the relationship between outcome reporting and PMWS using data from the publicly available Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine Outcome Monitoring Project (COMPare) [23]. PMWS was associated with the reporting of fewer non-pre-specified outcomes (p = 0.028) [17].

Timeliness of publication

Three studies looked at the timeliness of clinical trial reporting in articles developed with or without PMWS (Table 2) [15, 19, 21]. The only study investigating the complete manuscript development time, from last patient visit in clinical trials to article publication, showed that PMWS was associated with reduced time to publication [19]. Two studies investigating the timing of one step in the process, from manuscript submission to acceptance, showed inconsistent results [15, 21]. In the first of these studies, PMWS was associated with increased time from manuscript submission to acceptance, although the mean number of versions submitted was unchanged [15]; in the second study, time from manuscript submission to acceptance was reduced, but not significantly [21].

Conclusions

This systematic review aimed to identify and evaluate studies assessing the effects of PMWS on quality, ethics and timeliness of clinical trial reporting. Overall findings from eight studies assessing 849 articles developed with PMWS and 2073 articles developed without PMWS suggest a positive association between PMWS and improvements in clinical trial reporting. These results were consistent across measures of quality (adherence to CONSORT guidelines and quality of written English), ethics (reporting of non-pre-specified outcomes) and timeliness (time to publication). The improvement in CONSORT adherence associated with PMWS is perhaps unsurprising, given that professional medical writers are routinely trained in Good Publication Practice (GPP3) for the development of peer-reviewed manuscripts [25]; GPP3 guidelines state that authors should follow established reporting standards, including CONSORT [9, 10]. Although PMWS was associated with improved adherence to CONSORT, it was not associated with improved adherence to CONSORT-A. Due to word-count constraints, authors may prioritize the reporting of key results over methodology and protocol details in the abstract (which is all that is read by many readers). Thus, although professional medical writers improve disclosure overall, they may need to improve reporting in the abstract.

The improvements in manuscript quality may not be reflected by increased article impact and social media attention. In the one study identified in our systematic review, which examined measures of article impact, there were no significant differences between articles developed with and without PMWS in relation to Altmetric score, number of citations per year and number of article views per year. Medical publications professions have no influence on the subject matter or relevance of the clinical trial, and as such, PMWS may not be expected to affect an article’s post-publication impact.

It is important that authors remain transparent about which specific clinical trial outcomes will be measured and reported. The COMPare project determined the proportion of pre-specified and non-pre-specified outcomes that were reported in clinical studies published in the top five medical journals over a 3-month period [23]. In the present systematic review, one included study conducted a sub-analysis of the publicly available COMPare data and assessed the relationship between PMWS and outcome reporting. The authors found that fewer non-pre-specified outcomes were reported for articles developed with PMWS than for those developed without. This is not the only study to have shown a positive association between PMWS and publication ethics. For instance, a recent study showed that PMWS is associated with increased transparency relating to the source of funding, the author disclosures of financial interest and the acknowledgements of conflicts of interest (or lack thereof) in health economics and outcomes research publications [26]; another study showed that, of 214 publications retracted owing to misconduct between January 1966 and February 2008, only three declared PMWS [27].

One included study looking at the influence of PMWS on timeliness found that PMWS was associated with reduced time from last patient visit to article publication. This period includes processes in which professional medical writers are involved and have a major role, namely manuscript preparation, editing and submission. Two other included studies that examined the influence of PMWS on time from manuscript submission to acceptance revealed mixed results. One of the studies found that time to acceptance was reduced with PMWS, but that the difference was not statistically significant. The other study found that time to acceptance was increased with PMWS. This finding may reflect increased scrutiny by peer reviewers in industry-funded research publications (which are more likely to involve PMWS) [28, 29]; however, it should be noted that the period from submission to article acceptance is not primarily the responsibility of professional medical writers.

Clinicians have reported lack of time as a common reason for non-publication of research findings [30,31,32]. By specializing in preparation of clinical trial publications, professional medical writers are well placed to aid in the rapid dissemination of trial findings under the direction of the authors, subject to strict publication guidelines [10]. In fact, results from a recent survey showed that authors who use PMWS were more likely to have published as first author at least once in the previous 2 years [33], suggesting that PMWS can also improve overall publication rates.

This systematic review has some limitations, notably that study inclusion was largely based on the assumption that differences in outcomes were attributable to PMWS. It is possible that other factors caused these differences in quality and timeliness. This issue may affect the results of individual studies, but this systematic review combined results from different studies looking at different outcomes of interest, and showed a consistent benefit of PMWS on manuscript quality (including adherence to publication guidelines, quality of written English and publication in high-quality journals), ethics (reporting of pre-specified outcomes) and timeliness (time from completion of trial to publication). Taken together, the findings of this systematic review support the conclusion that PMWS has a positive impact on the high quality, ethical and timely dissemination of clinical trial data.

The included studies classified articles as having been developed with PMWS only when there was a clear acknowledgement of this support. As such, it is possible that some of the studies classified as having been developed with no PMWS might have had PMWS but had simply failed to acknowledge it. By classifying publications with no clear acknowledgment of PMWS as ‘without PMWS’, the studies identified in this systematic review may have underestimated the effects of PMWS. To minimize the risk of publication bias, we employed a broad search strategy with no limits on date, country, language or type of observational study. Most of the identified studies were sourced from conference proceedings (for which the full poster or oral presentation was available in 4/5 cases) and one was published in a non-peer-reviewed journal.

In the identified studies, the outcome measures chosen were widely accepted as measures of quality and completeness. For instance, CONSORT is an independently developed measure of reporting standards recommended by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors and also medical publications and medical writing societies, including ISMPP, EMWA and the American Medical Writers Association [10]. Other outcomes of interest assessed in this review were assigned independently of the investigators involved in each of the articles analysed in each included study (e.g. standard of written English—assessed during peer review of analysed articles [18]). As such, in this systematic review, we have been successful in analysing a range of outcomes assessed in observational (‘real-world’) studies in a standardized manner that minimizes publication bias.

Further research is needed to elucidate the role of PMWS in clinical trial publication, particularly with regard to productivity and added value [34]. Further research is also required to assess the impact of PMWS in other types of studies published by the pharmaceutical industry, such as observational studies and systematic reviews. As our systematic review identified that most studies of PMWS have only been presented at conferences or published in non-peer-reviewed journals, it is crucial that future studies are published in full in peer-reviewed journals [35, 36].

Currently, the pharmaceutical industry is more likely than non-industry institutions to disclose clinical trial results properly [37]. This is probably due to a larger investment in internal processes and infrastructure, which includes the use of PMWS. In fact, there have been calls for professional medical writers and publication experts to be employed by academic institutions [38, 39]. Additionally, in a survey looking at attitudes to PMWS, academic and clinician respondents to an online survey were generally accepting of PMWS, particularly its influence on editing, journal styling and adherence to reporting guidelines, with 84% of respondents stating that they valued PMWS [40]. In this survey, 82.9% of respondents felt that it was acceptable to receive PMWS; in another survey, PMWS was seen as ‘adding value to publication development’ by almost 90% of participants [41]. Our systematic review appraising current research in this area helps to substantiate the positive attitude to PMWS that is held by clinical and academic professionals seeking to ensure the ethical, accurate and timely publication of clinical trials.

Abbreviations

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- COMPare:

-

Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine Outcome Monitoring Project

- CONSORT:

-

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials

- CONSORT-A:

-

CONSORT for Abstracts

- EMWA:

-

European Medical Writers Association

- FDA:

-

Food and Drug Administration

- GPP:

-

Good Publication Practice

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- ISMPP:

-

International Society for Medical Publication Professionals

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- PMWS:

-

Professional medical writing support

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- RCT:

-

Randomized controlled trial

- RR:

-

Relative risk

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

References

World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310:2191–4.

Moher D, Glasziou P, Chalmers I, Nasser M, Bossuyt PM, Korevaar DA, et al. Increasing value and reducing waste in biomedical research: who's listening? Lancet. 2016;387:1573–86.

Baronikova S, Purvis J, Winchester C, Southam E, Beeso J, Panayi A. Disclosure of results of clinical trials sponsored by pharmaceutical companies. Curr Med Res Opin. 2018;34(Suppl 1):32 [poster 1].

Zwierzyna M, Davies M, Hingorani AD, Hunter J. Clinical trial design and dissemination: comprehensive analysis of clinicaltrials.gov and PubMed data since 2005. BMJ. 2018;361:k2130.

Goldacre B, DeVito NJ, Heneghan C, Irving F, Bacon S, Fleminger J, et al. Compliance with requirement to report results on the EU Clinical Trials Register: cohort study and web resource. BMJ. 2018;362:k3218.

Deane BR, Porkess S. Clinical trial transparency update: an assessment of the disclosure of results of company-sponsored trials associated with new medicines approved in Europe in 2014. Curr Med Res Opin. 2018;34:1239–43.

Miller JE, Wilenzick M, Ritcey N, Ross JS, Mello MM. Measuring clinical trial transparency: an empirical analysis of newly approved drugs and large pharmaceutical companies. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e017917.

Woolley KL, Ely JA, Woolley MJ, Findlay L, Lynch FA, Choi Y, et al. Declaration of medical writing assistance in international peer-reviewed publications. JAMA. 2006;296:932–4.

Battisti WP, Wager E, Baltzer L, Bridges D, Cairns A, Carswell CI, et al. Good Publication Practice for communicating company-sponsored medical research: GPP3. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163:461–4.

Winchester C. AMWA-EMWA-ISMPP Joint Position Statement on the role of professional medical writers. Write Stuff. 2017;26:7–8.

Kim MR, Nilsen J, Smith G, Hassan A, Silbiger S, Vivirito M, et al. Trends in medical writing acknowledgment in medical journals over the last decade. Curr Med Res Opin. 2011;27(Suppl 1):S13.

Nastasee SA. Acknowledgment of medical writers in medical journal articles: a comparison from the years 2000 and 2007. Curr Med Res Opin. 2010;26(Suppl 6):S6.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group TP. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535.

Mills I, Sheard C, Hays M, Douglas K, Winchester C, Gattrell W. Professional medical writing support and the reporting quality of randomized controlled trial abstracts among high-impact general medical journals. F1000Res. 2017;6:1489.

Gattrell WT, Hopewell S, Young K, Farrow P, White R, Wager E, et al. Professional medical writing support and the quality of randomised controlled trial reporting: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e010329.

Jacobs A. Adherence to the CONSORT guideline in papers written by professional medical writers. Write Stuff. 2010;19:196–200.

Gattrell W, Maisonobe P, de Abadal M. Outcome reporting, funding source and medical writing support in publications evaluated in the COMPare project. Curr Med Res Opin. 2017;33(Suppl 1):27.

Gattrell W, Farrow P, Costigan E, Sheard C, White R, Winchester C. Professional medical writing support increases the impact of articles reporting randomized controlled trials. Curr Med Res Opin. 2016;32(Suppl 1):S17.

Shah S, Nair S, Patil A, Naik S, Shah V. Role of medical publication professional in timely dissemination and transparent reporting of clinical data. Curr Med Res Opin. 2016;32(Suppl 1):S12.

Shah S, Patil M, Goriya V, Shah V. Adherence to Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines in manuscripts published from the Asia-Pacific region. Curr Med Res Opin. 2015;31(Suppl 1):S5.

Woolley K, Ely JA, Woolley MJ, Lynch FA, McDonald JM, Findlay L, et al. Declaration of medical writing assistance in international, peer-reviewed publications and effect of pharmaceutical sponsorship. Presented at the International Congress on Peer Review and Biomedical Publication, 16–18 September 2005 Chicago, USA. https://peerreviewcongress.org/abstracts.html. Accessed 22 May 2018.

Hopewell S, Collins G, Boutron I, Yu L, Cook J, Shanyinde M, et al. Impact of peer review on reports of randomised trials published in open peer review journals: retrospective before and after study. BMJ. 2014;349:g4145.

Goldacre B, Drysdale H, Powell-Smith A, Dale A, Milosevic I, Slade E, et al. The COMPare Trials Project. 2016. http://www.COMPare-trials.org. Accessed Mar 2018.

Hays M, Andrews M, Wilson R, Callender D, O'Malley P, Douglas K. Reporting quality of randomised controlled trial abstracts among high-impact general medical journals: a review and analysis. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e011082.

Wager E, Woolley K, Adshead V, Cairns A, Fullam J, Gonzalez J, et al. Awareness and enforcement of guidelines for publishing industry-sponsored medical research among publication professionals: the Global Publication Survey. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e004780.

Desai S, D'Angelo G, Panayi A, Baronikova S, Carter G, Evuarherhe O, et al. Involvement of medical writers in the development of health economic and outcomes research publications in inflammatory bowel disease – a systematic literature review. Curr Med Res Opin. 2017;33(Suppl 1):14.

Woolley K, Lew R, Stretton S, Ely J, Bramich N, Keys J, et al. Lack of involvement of medical writers and the pharmaceutical industry in publications retracted for misconduct: a systematic, controlled, retrospective study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2011;27:1175–82.

Kesselheim AS, Robertson CT, Myers JA, Rose SL, Gillet V, Ross KM, et al. A randomized study of how physicians interpret research funding disclosures. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1119–27.

Lippert S, Callaham ML, Lo B. Perceptions of conflict of interest disclosures among peer reviewers. PLoS One. 2011;6:e26900.

Glasziou P, Altman D, Bossuyt P, Boutron I, Clarke M, Julious S, et al. Reducing waste from incomplete or unusable reports of biomedical research. Lancet. 2014;383:267–76.

Scherer RW, Langenberg P, von Elm E. Full publication of results initially presented in abstracts. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007:MR000005.

Smyth R, Jacoby A, Altman D, Gamble C, Williamson P. The natural history of conducting and reporting clinical trials: interviews with trialists. Trials. 2015;16:16.

Duracinsky M, Lalanne C, Rous L, Dara A, Baudoin L, Pellet C, et al. Barriers to publishing in biomedical journals perceived by a sample of French researchers: results of the DIAzePAM study. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2017;17:96.

Lang T. Just who are we and what are we doing, anyway? Needed research in medical writing. Am Med Writing Assoc. 2009;24:106–12.

Carey LC, Stretton S, Kenreigh CA, Wagner LT, Woolley KL. High nonpublication rate from publication professionals hinders evidence-based publication practices. PeerJ. 2016;4:e2011.

Marchington JM. High non publication rate from publication professionals hinders evidence-based publication practices: a replication study in Europe. PeerJ Preprints. 2016;4:e2499v1.

Baronikova S, Purvis J, Southam E, Beeso J, Winchester C, Panayi A. Commitments by the biopharmaceutical industry to clinical trials transparency: the evolving environment. BMJ Evid-Based Med. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjebm-2018-111145 [Epub ahead of print].

Moher D, Altman DG. Four proposals to help improve the medical research literature. PLoS Med. 2015;12:e1001864.

Global Alliance of Publication Professionals (GAPP), Woolley K, Gertel A, Hamilton C, Jacobs A, Snyder G. Poor compliance with reporting research results – we know it's a problem ... how do we fix it? Curr Med Res Opin. 2012;28:1857–60.

Marchington JM, Burd GP. Author attitudes to professional medical writing support. Curr Med Res Opin. 2014;30:2103–8.

Camby I, Delpire V, Rouxhet L, Morel T, Vanderlinden C, Van Driessche N, et al. Publication practices and standards: recommendations from GSK Vaccines’ author survey. Trials. 2014;15:446.

Evuarherhe O, Gattrell W, White R, Winchester C. Association between professional medical writing support and the quality, ethics and timeliness of clinical trial reporting: a systematic review. Poster presented at the 2018 European Meeting of the International Society for Medical Publication Professionals (ISMPP), 23–24 January 2018, London, UK. 2018.

Acknowledgements

This work was presented as a poster at the 2018 European Meeting of the International Society for Medical Publication Professionals (ISMPP) [42] and was posted to bioRxiv as a preprint on 19 December 2018 (https://www.biorxiv.org/content/early/2018/12/20/501403). The protocol for this systematic review was posted on Research Registry on 13 December 2018 (ID: reviewregistry648). The authors would like to thank Charlotte Cookson and Gemma Carter for their assistance with reviewing this manuscript. The authors would also like to thank Dr. Shruti Shah for provision of a full poster for one of the identified congress abstracts.

Funding

This study was funded by Oxford PharmaGenesis.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The study was conceived by CW and drafted by OE, WG, RW and CW. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Obaro Evuarherhe, Richard White and Christopher C Winchester are employees of Oxford PharmaGenesis, Oxford, UK. William Gattrell is an employee of Ipsen Pharma, Milton Park, UK. Christopher C Winchester and Richard White are directors of, and own shares in, Oxford PharmaGenesis Holdings Ltd.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Evuarherhe, O., Gattrell, W., White, R. et al. Professional medical writing support and the quality, ethics and timeliness of clinical trial reporting: a systematic review. Res Integr Peer Rev 4, 14 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41073-019-0073-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41073-019-0073-7