Abstract

This article and the four videos linked to this article are a result of the earliest experiences in establishing an international research collaboration among seven countries in the Project Social and emotional experiences in transition through the early years. We draw attention to the complex issues surrounding the many processes, beliefs and attitudes about infants in research that permeated our processes of gaining ethical approval for the international study and which posed many challenges for our project. Through a process of reflective analysis, we have identified a range of ethical tensions and issues which the different countries involved in this international study faced in gaining ethical approval from their institutional ethical committees for their collaborative participation. More specifically, we identify one persistent tension concerning the use of video data in research on young children. This tension is a result of diverse interpretations of international ethical codes, alongside local restrictions and ethics review processes. It illuminates various positions concerning the protection of infants’ privacy versus the benefits of using non-anonymous video data both in joint analysis, and even further, in open publishing. Such positions have been widely debated in research with adults, whereupon many of the ethically challenging questions have been dealt with through processes of acquiring informed consents from the participants. In case of infants, however, the role and nature of informed consents is different from research with adults, as is the role of the adult in using infant ‘data’ in research. For most cases, informed consents are acquired from the parents or the legal guardians that are not necessarily present on a day-to-day basis in the actual data collection process in early years educational settings. The question of children’s own assents for study is widely debated and this is no less so in the project we present in this paper.

On the basis of the experiences in this international collaboration, and the challenges and tensions identified in between diverse cultural context and ethical review boards and practices, we propose that more dialogue in relation to research ethics on video research is needed within the diverse research communities and contexts, both locally and internationally. The dialogue is important to include also the representatives from the ethical committees, as the new (open) mediums for publishing are becoming more relevant and promising. Most important, ultimately, is the dialogue among the research participants, including where possible infants as contributors in their own right (as opposed to vulnerable subjects), and researchers in all phases of the research process.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

This article and the four videos linked to it are a result of the earliest experiences in the international collaboration among seven countries in the Social and emotional experiences in transition through the early years project as we sought to gain ethical approval to commence data generation with video. The seven teams are interrelated as a network and involve the 1) University of Waikato, New Zealand, 2) University of Strathclyde, Scotland, 2) University of São Paulo, Brazil, 4) University of Auckland, New Zealand (Samoa, Cook Island), 5) Monash University, Australia, 6) University of Jyväskylä, Finland, and 7) University of Arkansis, USA.

The research aim is to understand the complex intersubjective experiences of infants and their partners (parents, teachers, other children, among others) that take place when infants begin attending early childhood educational settings, also following the processes throughout the years of child’s attendance in early childhood education and care settings before entering school. The goal is to apprehend how participants’ social and emotional issues emerge in the transition from home care setting to care/education within collective educational settings where responsibility for care and education of the child is shared with the family. Moreover, the goal is to apprehend the emergence of discursive practices (Spink, 2000) dialogically unfolded by the interconnections of contexts (home/institution/work place) and regarding diverse cultures, with implications for policy and practice both locally and globally.

Methodologically, the study is based on the use of semi-structured interviews, structured observations and video recordings related to infant’s attendance in early educational settings. To enable the diverse data collection, each team submitted a research proposal for ethical review in their respective local Ethics Committees. These ethical review processes, however, have proved to be highly varied in length and in content in each country. They illustrate different approaches and tensions among the countries in relation to children’s and adults’ rights for expression, participation and voice, as well as participants’ rights for privacy and protection (see White, 2017a), producing significant challenges for the project. In this article, we will focus on the main tensions identified, namely, the tension between protection of children’s confidentiality and the benefits of using video scenes – as data and/or evidence - in research. In doing so we hope to illuminate the specific challenges and tensions that are faced in video research where the lives of infants and multiple nations are at focus.

As material to carry such discussion, we will use the first-hand experiences collected and documented in the processes of going through the ethical review processes in the various local Ethics Committees. The experiences are also documented and reflected in the videos (Additional file 1, Additional file 2, Additional file 3, Additional file 4), attached to this article.

General topic

For more than half a century the sciences have been facing international debates concerning ethics in research. Since the Code of Nuremberg (NIH 1947) landmark, many national and international debates, declarations and guidelines were implemented to organize research with human beings (WMA, 1964, WMA, 1975, WMA, 1983, WMA, 1989, WMA, 1996, WMA, 2000, WMA, 2002, WMA, 2004, WMA, 2008; International Ethical Guidelines for Biomedical Research Involving Humans, 1982; Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS), (1993) and World Health Organization (WHO), 1993, among others). The main goal was to guarantee the dignity of the research participants in addition to their physical, social and emotional integrity.

As a consequence of these statutes and guidelines, researchers are called to have a commitment with, and to, the participants. One of the first steps is that the participants should have autonomy to decide whether to collaborate (or not) with the study. Participants should be also protected by the researcher in the sense that the researcher both guarantees their anonymity but also safeguards their private life.

This debate has historically involved diverse struggles, divergences and confrontations. Due to particularities of the social sciences investigations, among the controversies is the use of videos as a registration method and as a way to present results, both of which are quite significant for the field. The use of video recordings has raised many challenging questions. How to make use of technology that results in exposure of the participant’s image, disregarding the rule of anonymity? How to ensure participants’ image protection, especially in the case of children (considered vulnerable)? Or, on the contrary, how can one not bring to visibility the intimacy of the participants’ lives, if the images give light to processes which cannot be made explicit by other resources? What are the losses to the field when it is defined by the non-exposure of the images? How to act as a researcher within these contradictions?

To unfold this debate, both perspectives will be first presented. Then, the positions of the Ethics Committees of some of the countries involved in this research project will be discussed.

Benefits of video methodologies in research with infants

For a long time, studies involving infants have been conducted only through direct observation, with immediate registration of certain behaviors, in loco and at the very moment in which they occur, based on pre-defined categories. However, throughout the 1970s and 1980s, anchored in major social and technological transformations, as well as in new research paradigms, a new role and importance was given to image, the knowledge in social sciences being greatly enhanced and transformed by the use of the audiovisual resources (Kreppner, 2001).

Given access to recorded image it became possible to watch several times and repeatedly the images minute by minute, second by second in slow or faster motion, with the preservation of the observed situation, allowing the possibility of an ongoing analysis process and more time for reflection about it, with the enrichment of the data interpretation (Carvalho et al., 1996; Jobim 2007). This use also allowed for extensive comparative analyzes of longitudinal observations, in which the observation seeks to capture either the behavior preservation or transformation, either diversity or specificity of a certain phenomenon (Kreppner, 2001). Additionally it provided a better way of giving visibility to precious cultural practices and nuances in interaction (White et al., 2015). Thus, previous reviews and discussions illustrated the strengths and benefits of using video methodologies in research, particularly with young children, helping the interpretation of children’s actions, interactions, experiences and communication (Fleer & Ridgeway 2014; White 2016; 2017a & b; Amorim et al. 2018; see also more generally in Erickson 2011).

As such, with the use of video-recordings, some of the behavior categories could also be better discriminated a posteriori (Kreppner, 2001). By being able to run a videotape many times, researchers can focus on different aspects of the situation not previously considered, with the possibility of creating new categories sometimes more adapted to the observed phenomenon. Thus, categories begun to be transformed, with a more complex presentation, proposed to apprehend behavior within their dialogical processes, through diadics and poliadics relations, capturing the dynamic movements, the bi-directionality of actions and even the participant’s (also the baby) co-participative role within relations (Marwick et al., 2013).

This shift towards the lived world of infants, as opposed to discrete and universally ascribed characteristics of infancy, was of utmost importance as the study of infants. However, it has consistently been positioned as ‘off-limits’ for pragmatic as well as ethical reasons – not least due to the distance among infants and adults, considering their language (verbal versus nonverbal) and developmental acquisitions. Simultaneously, cries for new and diverse ways of observing and listening to young children were emerging in the early years research community – establishing a need to investigate physical and emotional aspects of their lives (Delgado & Müller, 2005). Video methodologies, with the possibility to return and interpret the fleeting moments, nonverbal communication and interactions from diverse perspectives paved the way to an ongoing process of theoretical development and dialogicality in interpretations, as related to young children’s everyday lives in early years educational settings (White, 2017a). Video opened up interesting avenues not only for methodological debates but also for theoretical development in infant-toddler research and early childhood education and care (White, 2011a).

Increasingly, these methods are making evident the very precocious sensibility of the infant regarding to complex social communication processes, revealing the occurrence of mutuality, interruption, misunderstandings corrections, behavior of exclusion and integration, jealously and competition (Marwick, 2017), emotion (White, 2012) and, in general, challenging traditional assumptions concerning infant social competencies and relationships (White, 2011a & b; White et al., 2015). Focus of the analysis has moved from isolated behaviors, the camera being able to set in figure the I-other relation of the individual within society, through diverse historical, cultural and social contexts. Video scenes have been revealing aspects that are sometimes diffuse, turning them visible, enriching the knowledge and favoring the construction of a plurality of meanings (Jobim, 2007). Given the rapid and recent rise of infant participation in ECEC, the location has also shifted from the exclusive bounds of the private home to public spaces, such as the settings that comprise the study in question.

The use of video registrations in naturalistic environments is making it possible to have a greater knowledge of everyday life, habits, and routines of a phenomenon in which the infant is embedded. By repeatedly observing the scenes, one can be able to see recurrent patterns of interaction within specific environmental organization. Through the use of this method, specific communication and interaction practices has been revealed, which can be compared between different situations in time in the same environment or for similar situations in diverse types of context or cultural environments (Kreppner, 2001).

The use of videos can be strongly argued for also in terms of children’s rights to be heard and their rights for expression. Videos can offer means to give a voice to children and means for us adults to listen, and to interpret children’s experiences, even at their very young age (White 2017b; see also Additional file 1: Video S1 attached to this article.). Summoning the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, White has argued for the inclusion of infant voice in research as a serious provocation in educational and social research which otherwise denies their participation and, by association, capacity to be heard within and beyond the academy. Given the non-verbal language of infants, (White 2017b) further argues for the importance of video in particular as a central means of granting such voice in research that seeks to include their ‘voice’(s).

Despite this compelling argument for the participation of infants in research, the use of video scenes in research remains an object of considerable debate within many academies across the world. While social media and films such as the movie “Bébés” (2010) http://www.imdb.com/title/tt1020938/ has long since positioned infants as interesting and worthy subjects in video documentary; and key early childhood activists have included images of infants in film (see Gaffney & White, 2018), when it comes to ‘scholarly’ research there are lingering problems. The tension that arises here is that through their presentation, video exposes the participants’ identity and privacy, and, in the case of infants, does so without ‘consent’ of the infant him or herself, thus transgressing the established ethics norms that have been inherited through scientific research antecedents. Thus the problems in the interpretations of infants as able to grant consent (or assent), issues of privacy and associated interpretations of what constitutes ‘best interests’ of the child, as determined by the academy in the first instance. It is to these we turn next.

Participants’ rights for privacy and confidentiality

Based on the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948), the Declaration of the Rights of the Child (1959), the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (1966), and others, the issue of image exposition became a subject of debate more properly in the decade 1960. This evolved greatly and contemporarily the discussion about the right to the image has become extremely relevant and controversial, in addition to the conflicts surrounding research. The widespread use of technologies (as cell phones with cameras), television media, virtual networks and social media allowed the dissemination of images with an extreme speed and ease. It thus became as a juridical good easily violable, constituting a legal problem (Jobim 2007; Rodrigues, n.d.).

Discussions of the importance of standardization of image use increased, as people became more and more vulnerable to non-consensual exposure of their image. Faced with this, the doctrinal position regarding the right to the image, has sought to establish its limits. Each country began to legally regulate the use of people’s image, the legal issues expressing the rights of physical, moral and intellectual integrity, searching for the preservation of the identity, values, ideas and beliefs, spaces and personal objects. The principle of freedom unfolded increasingly also highlighting the right of privacy and intimacy (United Nations, 1959, United Nations, 1966a, b; CIOMS, 1993; Medical Association, 1969, WMA, 1975, WMA, 1983, WMA, 1989, WMA, 1996, WMA, 2000, WMA, 2002, WMA, 2004, WMA, 2008).

However, as the right to the image is a subjective right, it guarantees the holder the possibility of allowing (or not) the capture and reproduction of his/her image according to his/her interest, through a consent, which shall express a bilateral agreement, forming a contractual relationship. Once the holder of a certain image authorizes its use, images become permissible. It occurs, though, that the consent must be interpreted restrictively, since the assent of the recording does not necessarily include its publication; nor does the agreement with the publication cover diverse public uses. For some authors, perspectives and countries as Brazil, the disclosure of the image should therefore take place according to a contractual term, generating obligations from both parties. According to this view the use of the image without the authorization of the holder therefore constitutes a violation of the person’s right according to this view (Ramos, 2010; Franciulli Neto, 2004).

But still, even with a consent agreement, there remains a problem in research. This concerns how to conduct investigations with the commitment of protecting the image and privacy of the participants if researchers need to make use of them, even if their quest is to contribute to the knowledge economy? How to work that issue taking the researchers’ ethical commitment to confidentiality as a point of departure, while videos, by default, include identifiable material?

The traditional commitment to protection of privacy of the participants and confidentiality becomes thus an issue. Moreover, even if the knowledge developments, addressed earlier in this text, have already proved the benefits of video methodologies, it can be in clear conflict with the ethical commitment to hide the identity/intimacy of the participants of the research according to some ethics-granting academies (Amorim et al. 2018; see also attached Additional file 3: Video S3). In the current project such issues have been addressed in very different ways by the countries through the Ethics Committees, based on different interpretations of what constitutes ethical practice in video research with infant subjects.

Results

The challenges in the international collaboration with video methodologies

Returning to the international collaboration discussed here, one of the main ethical tensions identified has been related to this seeming ‘impasse’ between protection of participants’ privacy and confidentiality, in contrast to the benefits of using non-anonymous video data, both in joint analysis and publications. This tension became particularly clear in the intention to share video data from different countries’ early years educational settings aiming at joint analysis among the seven international research teams. The project was also challenged in some of the countries by the ethical committees because of the intention to publish the videos in the research reports, openly, in a non-anonymous ‘open’ format, in video journals such as Video Journal of Education and Pedagogy. As the first journal of its kind, launched in 2016, this journal set the course for such debates to take place, and commenced important discussions concerning ethics for young children.

Sharing the data

In an international collaboration there are additional challenges. One of the first of these, for the current project, related to the intention to share the video data for joint analysis. In some of the participating universities of this collaboration, the ethical committees requested a solution that would guarantee, from their point of view, a secure data management and confidentiality of video data. For example, at Monash University, Australia, University of Jyväskylä, Finland and University of Strathclyde, Scotland, the video data can be only stored into a locally operated data storage, not into a joint or shared storage with other countries and teams (as was the case for New Zealand who utilized google docs and, consequently, were able to share their data with the international team online). Other teams can view the data after a specific request to the locally operated data storages, and in Scotland the local cloud storage offers the capacity for other countries to upload their data to the system as part of shared group access. At the University of São Paulo however, the video data cannot be shared openly, neither stored in local data storage for other teams to access. Some scenes can be observed together, but only after editing and selecting particular scenes with the researcher who conducted the data collection and knows thoroughly the agreement made with the participants (Additional file 3: Video S3). As a consequence the project has had to explore other alternatives for data sharing and analysis – often expensive (i.e. having to travel to view the footage), inefficient (for instance, we are unable to analysis the footage online) and limiting (in that other countries can only view what the researchers in that country deem to be ‘viewable’).

Together with the question of data sharing, another challenge emerged. In the Finnish case (Additional file 4: Video S4), University of Jyväskylä ethics committee paid attention to the implications of the new personal data protection regulation in European UnionFootnote 1 for the collaboration. Because some of the participating countries are outside EU/EEA area, the ethics committee was concerned about the lack of knowledge about the regulations that these countries apply. To continue with this project, the ethics committee proposed a solution: the information letter and the form for obtaining informed consents should include a statement that this project includes collaboration and data sharing with countries that lack an EU commission decision about the data security level. In this way, the teachers and parents of the children would have more awareness about the diversities in the countries to be able to judge if they want to participate or allow their child to participate to the study (see later more details in ‘Informed consents’; Additional file 4: Video S4). The assumption by one set of countries that another set of countries lack the same ethical standards sets an unhelpful precedent for international scholars working together for a common goal.

Open publishing

In addition to sharing the videos for analysis, some of diversities among the collaborating countries were visible in relation to open publishing of the videos in the research reports. As a starting point, all the video recordings done for this international collaboration are planned to be done in early education settings outside the child’s home, in public spaces. Ethics agreements across different countries held a somewhat different emphasis in relation to the public nature of the institutions involved. In some contexts, a research culture in early childhood education and care had been built that accepted and even valued openness (largely based on existing relationships with researchers and a research culture in the ECEC services themselves). In such cases, as in New Zealand, diverse researcher-practitioner collaborations are undertaken openly (based on the legacy of ‘Centres of Innovation’Footnote 2), and the participant ECEC institutions are openly acknowledged for their contributions if they wish to be (as part of the ethical agreements undertaken). In other countries in the project (e.g. Finland and Brazil), this option is not traditionally given and the ECEC institutions are anonymized from the outset.

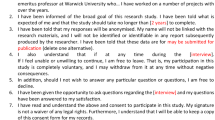

Informed consent

All seven countries and the ethical codes applied in these universities who are involved in the project, require that an informed consent will be acquired from the participants (parents, teachers and institutional staff) and, particularly related to infants, from the parent or legally authorized guardian of the children. For each participating country, their informed consent had to be written in a very detailed way, to allow the participants, in this case guardians/parents, to make a decision about the diverse data collection methods and treatments of the data (such as option for open publishing, blurring of the images or no open publishing). While this level of rigour was generic across all sites, there were a number of differences in the responses offered by ethics committees and the way participant rights were interpreted against the use of video data concerning privacy and open access in particular.

The process of gaining informed consents reflect very diverse research cultures present in the collaborating countries. The University of Auckland team, who conduct the study in Cook Island and Samoa will follow not only the ethical guidelines of the academy but also Pasific research guidelines in each country - they discuss their collaborative approach with the participants (see Additional file 2: Video S2). In this case no confidentiality can be assumed in the sense that results are kept away from the participants, but instead the process will be dialogued with the participants, as talanoa (Airini et al., 2009). Face-to-face encounters are at utmost importance and the boundaries for this research collaboration is continuously negoatiated. However, as the University of Auckland team discusses in the video, the contexts in Samoa and Cook Island still have differences in terms of how and from whom to gain formal consent for the study (see Additional file 2: Video S2). At the time of writing, this issue had not been resolved.

The teams at the University of Jyväskylä, Finland, and at the University of Strathclyde, Scotland, on the other hand, have been engaged with the interpretation of the new regulations that come to action and direct research practices within European Union, particularly, in relation to the use and collection of personal data after the application of the EU Personal Data Regulation. As a result the researchers have to give information about the international collaboration with countries and teams that operate outside EU/EEA region, with countries that lack a EU commission decision about the data security level. (Additional file 4: Video S4.) Even in Brazil, outside EU/EEA area, the team at the University of São Paulo has also engaged in lengthy dialogue with the ethical committee in terms of the open use of data: the protective measures are clear and the lack of confidentiality needs to be expressed to the participants. They are also proposing participatory approaches with the participants, as with the University of Auckland team. (Additional file 3: Video S3.).

New Zealand also, in the promotion of ‘teacher-researchers’ devised a way of involving ECEC services in the study far beyond traditional forms of involvement. Nonetheless, neither they, nor any of the other sites, were able to resolve the dilemma of infant consent (and this point is raised also by the Australian team – video) beyond continued vigilance concerning the comfort of the infant themselvesFootnote 3 – which was monitored carefully by the teacher-researcher on the days of recording and in discussion with the lead researcher following each session. These ethical issues are ongoing and call upon a complex combination of value-driven, moral, and duty-oriented responses – across processes of data generation, production and dissemination (Lester, 2018).

Discussion

As discussed above, during the last fifty years, in the social sciences, video recordings have been one of the fundamental resources for the apprehension of the processes of transformation and stability of the behavior and the development of infants and young children. The advantages of using this feature are inestimable, which have already modified both theoretical and methodological paradigms in the study of such processes in very young children, allowing the understanding of the interwoven of biological-cultural elements that participate in the process of constitution of the child, in diverse environments and conditions. Skills considered not expected have been verified, with significant implications in social intervention processes in childcare practices, as in collective educational settings.

However, the field of research ethics have been debating and seeking to organize human research, with the goal of establishing norms that point to the limits of the researcher in his/her investigation, guaranteeing protection to the participants. The prerogatives of ethical norms seek to guarantee the dignity of participants who collaborate in the construction of knowledge and science, pointing to their anonymity and physical and moral image protection, as well as the protection of their privacy. These so-called ethical norms are called into question in international projects, such as ours, that include infants. They are further compromised in the wake of recent technologies “that make it easier than ever for citizens to invade one another’s privacy rights…” (Lester, 2018, p. 15).

These measures problematized the use of video recordings as by default they include identifiable material. In research with adults, these tensions between openness and rights for privacy and anonymity, and other ethically challenging questions can be more easily dealt with the process of acquiring informed consents from the participants. However, such questions are being considered more critically when the image involves an infant, child, adolescent or a person whose autonomy is reduced, recognizing their peculiar situation of vulnerability, regardless of the risk level of the research, while simultaneously unleashing developmental strongholds on infants to portray them as participants in the research process.

Researchers are then facing a dilemma that is more ethical than legal. How to act ethically when videotaping and presenting images of children (considered vulnerable)? How to act ethically to videorecord them in naturalistic environments, in their private lives? How to contribute to the advancement of knowledge, without disrespecting the honor and the intimacy of the participants? How can we not expose the intimacy of the child’s, his/her companions and relatives life, if the image presentation gives light to processes that are poorly shown by other resources?

These dilemmas are being analyzed and dealt with in varying ways by the national and local Ethics Committees of the diverse countries. Committees have been organizing their norms since the Code of Nuremberg (NIH 1947) landmark, after which many national and international debates, declarations and guidelines were implemented (particularly the WMA, 2008) to organize research with human beings. Guided by universal ideals that are described and assigned by member states, there have been a complex, cultural-specific domestication (Alasuutari & Alasuutari 2012) of the universal signed commitments. The domestication framework claims that exogenous policy models and arguments are actively adapted and adopted by nation-states, and in this process the actual practices inflicted by the global blueprints are significantly shaped by local conditions and discourses (Alasuutari 2009). In this manner, the meaning and consequences of the practices can be significantly different from the origin, despite being veiled in universal rhetoric (Rutanen, Amorim, Colus, & Piattoeva 2013).

As could be seen in the four videos and discussion above from the Ethics Committees’ definitions of the local research projects, while appropriating the universal propositions, similarities of concerns with participants are found across Committee resolutions. But differences were also identified, and it is to these we have needed to direct our attention in the development of the project.

In all the countries, the participants and children’s parents/guardians signed an agreement about the use of video in open-access publications. The options were given to publish the image either openly, blurring it, or not publishing it at all. In addition, in some countries some particular steps was agreed to be taken before the publication. For example, for Auckland research group, based on a collaborative approach, the results of the analysis should be first discussed with participants, who would allow (or not) the presentation.

In case of children, more specifically of infants, the role and nature of informed consents are different from research with adults. For most cases, informed consents are acquired from the parents or the legal guardians that are not necessarily present on a day-to-day basis in the actual data collection process in the early years educational settings. This follows the international ethics agreements, where parents or legal guardians are entitled to evaluate the situation for their child and make an informed decision about the participation – or refusal to participate the study, and to indicate this by signing the consent. The parents and the legal guardians have to rely on the information given by the researcher about the process, and to make decision about the participation. Children are however, the ones whose lives are being recorded and they engage with and live the actual research in practice. This leads to address the question of children’s own assents. When we are studying very young children, we should critically ask, in the words of the Australian team “What does assent look like?” (Additional file 1: Video S1). Further, issues in relation to the length of time for which consent or assent for a child’s image to be presented publically have had to be considered, and whether that consent and assent needs to be revisited as the child grows and becomes an adult. These questions continue to arrest our attention.

Conclusions

On the basis of the experiences in this international collaboration, and the challenges and tensions identified in between diverse cultural context and ethical review boards and practices, we propose that much more dialogue in relation to research ethics on video research is needed within the diverse research communities and contexts, both locally and internationally. The dialogue is important to include also the representatives from the ethical committees, as the new (open) mediums for publishing are becoming more relevant and promising, as shown with our case in infant-toddler research. It is also important when contemplated against increasing global demands for understanding, where knowledge crosses cultural, geographical and ideological divides. Most important, ultimately, is the dialogue among the research participants, including adults, children, and researchers in all phases of the research process. The dialogue could be characterized as a partnership among the participants and the researchers, aiming towards an open dialogue both about the constraints in the data use and, further, in interpretation of children’s everyday life, development and experiences from diverse viewpoints (Amorim et al. 2018).

Finally, our experiences in this international collaboration leads us to emphasize that the difficult question of children’s assents for study is a topic that the research community and researchers on infant-toddlers and early years settings needs to be addressed yet in more detail within and beyond the scholarly community (Additional file 1: Video S1, Additional file 2: Video S2, Additional file 3: Video S3 and Additional file 4: Video S4; also White 2017b; Amorim et al. 2018). We assert that such dialogues should seek to open up the potential for video with infants and across communities rather than shutting such rich interpretative and agentic possibilities down from the outset. Our work in this regard – both in the project and within the wider research domain – is only just beginning:

"We need to understand that every human being has the capacity to contribute and what we need to do is be part of a culture and a society and a world that celebrates those differences… we all have the capacity to contribute. Its just a matter of creating a climate where we all are allowed to continue…. And that only happens through dialogue." (Lester, 2018, p. 164).

Notes

Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data, and repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation) The Regulation will enter into force on 24 May 2016, it shall apply from 25 May 2018. http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=uriserv:OJ.L_.2016.119.01.0001.01.ENG&toc=OJ:L:2016:119:TOC.

Centres of Innovation was a government funded research initiative that supported teachers in ECEC services to undertake research in collaboration with researchers, including the use of video. It created a culture of teachers-as-researchers rather than teachers as merely receivers or donors of research. See, for example. Meade, 2015. Moreover, it legitimized video as a pedagogical research tool for both inquiry AND dissemination.

For example, if an infant appeared to be avoiding the researcher who was filming, or showed signs of anxiety about the camera being on, the filming ceased on that day. The involvement of teacher-researchers – that is, teachers who already knew the infant and centre as opposed to a stranger – meant that such forms of assent were much more possible.

Abbreviations

- CIOMS:

-

Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences

- ECEC:

-

Early childhood education and care

- EEA:

-

European Economic Area

- EU:

-

European Union

- GDPR:

-

General Data Protection Regulation; Regulation 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data, and repealing Directive 95/46/EC

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- WMA:

-

World Medical Association

References

Airini TVM, Sauni LS, Leaupepe M, Pua V, Tuafuti P (2009) This road belongs to me: Promising practices in distance education. In: Jensson J, Carpenter VM, Mclean M, Stephenson M, Airini (eds) University Teaching Reconsidered: Justice, practice, inquiry. Dunmore Press, Wellington, pp 79–92

Alasuutari P (2009) The domestication of worldwide policy models. Ethnol Eur 39(1):66–71

Alasuutari P, Alasuutari M (2012) The domestication of early childhood education plans in Finland. Global Social Policy 12(2):129–148

Amorim KS, Dentz MV & Costa NMS (2018) Videogravação nas Ciências Humanas: O dilema entre potencial da imagem e direito de preservação da identidade. In Leme M I S, Cagnin S & Leite S A S (eds) Pesquisa aplicada em Psicologia: implicações éticas. Campinas: Mercado das Letras, pp 13-48.

Carvalho AMA, Bergamasco NHP, Lyra CDP, Pedrosa MIP, Rubiano MRB, Rossetti-Ferreira MC, Oliveira ZMR, Vasconcellos VMR (1996) Registro de Vídeo na Pesquisa em Psicologia: Reflexões a partir de Relatos de Experiência (Videorecordings on developmental research: reflections based on experience reports). Psicologia Teoria e Pesquisa 12(3):261–267

CIOMS (1993) International Ethical Guidelines for Biomed Res Involving Humans. https://cioms.ch/wpcontent/uploads/2016/08/International_Ethical_Guidelines_for_Biomedical_Research_Involving_Human_Subjects.pdf. Accessed 6 Nov 2017.

Delgado AC, Müller F (2005) Em busca de metodologias investigativas com as crianças e suas culturas (searching for investigative methodologies with children and their cultures). Cad Pesqui 35(125):161–179

Erickson F (2011) Uses of video in social research: a brief history. International journal of social research methodology, issue 3: video based. Soc Res 14(3):179–189 https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2011.563615

Fleer M, Ridgeway A (eds) (2014) Visual methodologies and digital tools for researching with young children: transforming visuality. Springer, Dordrecht

Franciulli Neto D (2004) A proteção ao direito à imagem e a Constituição federal (the protection for the right to image and the Federal Constitution). Informativo Jurídico da Biblioteca Ministro Oscar Saraiva 16(1):1–74 http://www.stj.jus.br/publicacaoinstitucional//index.php/informativo/article/view/442/400. Accessed Apr 08 2017

Gaffney, M. & White, E.J. (2018, in press). Video activism as political advocacy for social justice: The legacy of Professor Anne Smith in education. Video Journal of Education and Pedagogy.

Jobim Souza S (2007) Dialogismo e alteridade na utilização da imagem técnica em pesquisa acadêmica: questões éticas e metodológicas. In: (Dialogism and alterity in the use of image tecnique in academic research: ehtical and metholofogical issues) Ciências Humanas e pesquisa: Uma leitura de Mikhail Bakhtin. Cortez, São Paulo, pp 77–94

Kreppner K (2001) Sobre a maneira de produzir dados no estudo da interação social (about the way to produce data in social interaction studies). Psicologia: Teoria e Pesquisa 17(2):97–107

Lester PM (2018) Visual ethics: A guide for photographers, journalists and filmmakers. Routledge, New York & London

Marwick H (2017) Supporting concordant intersubjectivity and sense of ‘belonging’ for under three-yearolds in early years settings. In: Dalli C, White J (eds) Under three year olds in policy and practice. Springer Publications, Singapore, (p 101–122)

Marwick H, Doolin O, Allely CS, McConnachie A, Johnson P, Puckering C, Golding J, Gillberg C, Wilson P (2013) Predictors of diagnosis of child psychiatric disorder in adult-infant social-communicative interaction at 12 months. Research in Developmental Disabilities 34:562–572

Meade A (2015) Catching the Waves: Innovation in Early Child Educ, Wellington. New Zealand Council for Educ Res, New Zealand http://www.nzcer.org.nz/nzcerpress/catching-waves-innovation-early-childhood-education?cPath=139_133_44&products_id=1334 Accessed 31 Mar 2018

NIH (1947). Nuremberg Code. https://historynihgov/research/downloads/nurembergpdf Accessed 6 Nov 2017

Ramos N (2010) Cinema e pesquisa em ciências sociais e humanas: contribuição do filme etnopiscológico Para o estudo da infância e culturas (cinema and research in human and social sciences: contribution of etnopsychological movie for the study of infancy and culture). Contemporânea, 8(2). https://portalseer.ufba.br/index.php/contemporaneaposcom/article/view/4817/3575. Accessed Apr 25 2017

Rodrigues R B (n.d.) Direito à imagem e dano moral: reparação por meio de indenização pecuniária (Right to image and moral damage: amendment through pecuniary compensation). Revista dos Estudantes de Direito da UnB, 7ª Edição. http://www.arcos.org.br/periodicos/revista-dos-estudantes-de-direito-da-unb/7a-edicao/direito-a-imagem-e-dano-moral-reparacao-por-meio-de-indenizacao-pecuniaria. Accessed 26 Mar 2017

Rutanen N, Amorim K S, Colus K, Piattoeva N (2013) What is Best for the Child? Early Childhood Education and Care for Children under 3 Years of Age in Brazil and in Finland. International Journal of Early Childhood 45:1–21

Spink MJ (2000) A ética na pesquisa social: da perspectiva prescritiva a interanimacao dialógica (Ethics in social investigation: from a prescriptive perspective to a dilogical interanimation). Psico (Porto Alegre) 31(1):7–22

United Nations (1959) Declaration of the rights of the child. New York. http://www.cirp.org/library/ethics/UN-declaration/. Accessed 6 Nov 2017

United Nations (1966a) Universal declaration of human rights. http://www.un.org/en/universal-declaration-human-rights/index.html. Accessed 6 Nov 2017

United Nations (1966b) International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. https://www.un.org/ruleoflaw/blog/document/international-covenant-on-civil-and-political-rights/ Accessed 6 Nov 2017

White E J (2011a) Summary: Lessons learnt and future provocations. In E Johansson E & White E J (eds), Educational Research with Our Youngest: Voices of Infants and Toddlers (pp. 185–202). Springer. Dordrechdt, The Netherlands

White, E.J. (2011b). “Now you see me, now you do not”: Dialogic loopholes in authorship activity with the very young. Psychology Research 1(6)

White E J (2012) Cry baby, cry: A dialogic response to emotion. Mind, Culture and Activity 20(1):62–78

White J (2016) More than meets the “I”: A polyphonic approach to video as dialogic meaning-making. Video Journal of Education and Pedagogy 1(6). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40990-016-0002-3

White E J (2017a) The ‘work of the eye’ in infant research: A visual encounter. In Li L, Quinones G & Ridgway A (eds) Studying Babies and Toddlers: Relationships in Cultural Contexts (pp. 123–136) Springer: Dordrechdt, The Netherlands. http://link.springer.com/book/10.1007%2F978-981-10-3197-7

White J (2017b) Video ethics and young children. Editorial. Video Journal of Education and Pedagogy 2(2). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40990-017-0012-9

White E J, Peer M & Redder B (2015). Infant-teacher dialogues: A pedagogical imperative? Early Childhood Quarterly 30: 160–173. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0885200614001197

WHO (1993). Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMxS)

WMA (1964) Helsinki declaration. https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki-ethical-principles-for-medical-research-involving-human-subjects/ Accessed 6 Nov 2017

WMA (1975) Helsinki declaration. https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki-ethical-principles-for-medical-research-involving-human-subjects/ Accessed 6 Nov 2017

WMA (1983) Helsinki declaration. https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki-ethical-principles-for-medical-research-involving-human-subjects/ Accessed 6 Nov 2017

WMA (1989) Helsinki declaration. https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki-ethical-principles-for-medical-research-involving-human-subjects/ Accessed 6 Nov 2017

WMA (1996) Helsinki declaration. https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki-ethical-principles-for-medical-research-involving-human-subjects/ Accessed 6 Nov 2017

WMA (2000) Helsinki declaration. https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki-ethical-principles-for-medical-research-involving-human-subjects/ Accessed 6 Nov 2017

WMA (2002) Helsinki declaration. https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki-ethical-principles-for-medical-research-involving-human-subjects/ Accessed 6 Nov 2017

WMA (2004) Helsinki declaration. https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki-ethical-principles-for-medical-research-involving-human-subjects/ Accessed 6 Nov 2017

WMA (2008) Helsinki declaration. https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki-ethical-principles-for-medical-research-involving-human-subjects/ Accessed 6 Nov 2017

Acknowledgements

This article is a response to the discussion started by Jayne White in the editorial Video ethics and young children, published in Video Journal of Education and Pedagogy 2017, 2. This article includes video presentations by group members of Social and emotional experiences in transition through the early years:

1. Monash University team: Rivalland, Corine, Monash University, Australia email:corine.rivalland@monash.edu and Monk, Hilary, Monash University, Australia, email: hilary.monk@monash.edu. Video 1: Australian study (4.03 min).

2. University of Auckland team: Toso, Meripa, University of Auckland, New Zealand, email: m.toso@auckland.ac.nz, Baice, Tim (Ministry of Education Samoa), University of Auckland, New Zealand, Leaupepe, Manutai (Cook Islands) University of Auckland, New Zealand & Ravlich, Elisabeth (Cook Islands), University of Auckland, New Zealand. Video: International infant transition project. University of Auckland (4.30 min).

3. University of São Paulo: Amorim, Kátia, S., University of São Paulo, Brazil, email: katiamorim@ffclrp.usp.br Video: The Brazilian case (5.22 min).

4. University of Jyväskylä: Rutanen, Niina, University of Jyväskylä, Finland, email: niina.a.rutanen@jyu.fi Video: The Finnish case. Video research in early childhood education and care (4.11 min).

Funding

In Brazil, FAPESP (number 2016/24717–0) and CNPq (304351/2016–4), has supported the planning, collection, analysis of the data as well as in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The four videos supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article and its additional files.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

As one of the lead researchers on this project JW initiated the idea by invited contributing countries to create short videos to explain their ethics processes which she presented at the Association of Visual Pedagogy Conference in Denmark 2017. At her invitation NR and KA wrote the article in collaboration with HM and JW, using, as a starting point the material provided in the four videos attached to the article. The collaborating research teams from the international project who contributed to the videos are named in the Acknowledgements. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Consent for publication

The consent to publish the images visible in the four videos have been obtained from the participants in the videos, and children’s parents or legal guardians.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Infants consent and video capture: an Australian perspective. (MP4 39521 kb)

Additional file 2:

Infant transition project: Pacific Islands' case. (MP4 49403 kb)

Additional file 3:

The dilemma between image use and the right to anonymity. (MP4 91937 kb)

Additional file 4:

Some implications of General Data Protection Regulation in EU: a Finnish case. (MP4 55944 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Rutanen, N., Amorim, K.d., Marwick, H. et al. Tensions and challenges concerning ethics on video research with young children - experiences from an international collaboration among seven countries. Video J. of Educ. and Pedagogy 3, 7 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40990-018-0019-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40990-018-0019-x