Abstract

Background

This review provides an in-depth investigation into the difficulties facing older Australians when accessing health care services.

Methods

A literature search was conducted in December 2016 using Academic Premier to identify relevant publications. Key search terms were accessibility, health service, older people and Australia. Papers published between 1999 and 2016 were included. Statements of accessibility were extracted and then grouped using the five dimensions of accessibility by Penchansky and Thomas (1981): availability, accessibility, accommodation, affordability and acceptability.

Results

Forty-one papers were included. Availability issues identified were inadequate health care services, particularly for culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) populations and those residing in rural areas. Accessibility issues included difficulties accessing transport to health care services, which in turn restricted choice of appointment time. Issues of accommodation identified were long waiting times for appointments with both general practitioners and medical specialists. Affordability was a common problem, compounded by multi-morbidity requiring high health care use. Issues of acceptability centred on the role of the family, feelings of shame when receiving care from a non-family member, traditional practices and gender sensitivity.

Conclusions

The contribution of factors to health service accessibility varies according to an older person’s geographical local and their accessibility to transport, as well as their level of multi-morbidity and cultural background. Improving access to health services could be improved by matching services to the population that they serve.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Over the past century, average Australian mortality rates have fallen significantly, with life expectancies rising for both men and women [1]. This fall in mortality rate has added to population growth and the proportion of older people in the Australian population. In 2015, there were an estimated 3.5 million older Australians, representing one in every seven people (15.1%); this proportion has increased from 13.3% in 2009 to 14.3% in 2012 [2].

The impending rapid growth of Australia’s older population has important implications for provision of services needed by older people [3]. Our ageing population challenges the ability of health services to maintain health and wellbeing, manage serious and continuing illness and provide support for older people with frailty and/or disability [4]. This challenge is not only because there are many more Australians surviving to old age than was the case for previous generations, but it may well be that on average they have more co-morbidities requiring higher levels of care than earlier generations [3].

In 2015, the Australian Bureau of Statistics identified that 94.8% of older people lived in households [2]. This highlights Australia’s federal government policy of ‘ageing in place’, wherein the objective is to maintain older people in the community for as long as possible, whilst reducing morbidity, hospitalisation and admission to aged care services [5]. Ageing in place aims to provide support for older people so that they can live where they choose for as long as they can. As the population of Australia ages, it is critical that older adults, their families, healthcare providers and healthcare systems are equipped to deal with the challenges of cultural diversity and heterogeneity in ageing. Concomitantly, arrangements for the delivery of Australian aged care services have changed dramatically in recent times [6].

As the length of life and proportion of older persons increase in most industrialised and many developing nations, a central question is whether this population ageing will be accompanied by sustained or improved health, improved quality of life and sufficient social and economic resources [7]. Access to appropriate and adequate services has the potential to minimise risk and enhance well-being and, in turn, reduce the need for acute hospital admissions and delay entry into long-term residential care [8]. A range of factors interact to influence a patient’s ability to access health care at any point in time. Penchansky and Thomas have defined the following five dimensions to describe accessibility: availability, accessibility, accommodation, affordability and acceptability [9].

Method

Search strategy

The review was undertaken in December 2016 and used the Academic Search Premier database to identify relevant articles. This multidisciplinary research database provides access to academic journal articles, newspapers and magazines. Key search terms were purposely kept broad and included ‘accessibility’, ‘health service’, ‘older people’ and ‘Australia’.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Only English-language papers published between 1999 and 2016 were included. Abstracts were screened by the first author and discarded if the article did not contain any information on the accessibility of older Australians to healthcare services. The full texts for all selected abstracts were retrieved and then assessed for inclusion by both authors. Any disagreement over inclusion of the full articles was resolved through face-to-face meetings. A lateral search was also performed by both authors to identify additional articles using the reference lists of identified articles. No further studies were identified during the lateral search.

Inclusion criteria included publication in peer-reviewed academic journals. Because we were looking for specific issues related to healthcare accessibility for older Australians, no restriction was placed upon what publication type. Accordingly, our review included original articles, systematic reviews, opinion pieces and editorials published in academic journals. Regarding participants, we included all publications involving and/or discussing older Australians (aged 65 years and over). Studies including migrants and Indigenous older Australians were also included, with an age ≥ 50 years defining ‘older person’ for Indigenous Australians. Excluded were papers focusing outside of Australia and studies of health service accessibility not specifically including older adults.

Data extraction and analysis

Both authors agreed upon the search strategy and the inclusion/exclusion criteria before the study’s inception. Full papers identified during the literature search were exported by the first author into an Excel spreadsheet for analysis. The included papers were sorted by both authors into Penchansky and Thomas’ five dimensions of accessibility: availability, accessibility, accommodation, affordability and acceptability [9], as defined below:

-

Availability as the relationship between the volume and type of existing services (and resources) and the clients’ volume and types of needs. Availability refers to the adequacy of the supply of physicians, dentists and other providers or facilities, such as clinics and hospitals and of specialised programs and services, such as mental health and emergency care [9];

-

Accessibility as the relationship between the location of supply and the location of clients, taking account of client transportation resources and travel time, distance and cost [9];

-

Accommodation as the relationship between the manner in which the supply resources are organised to accept clients (including appointment systems, hours of operation, walk-in facilities, telephone services) and the clients’ ability to accommodate these factors [9];

-

Affordability as the relationship between the prices of services and providers’ insurance or deposit requirements and the client’s income, ability to pay and existing health insurance. Client perception of worth relative to total cost may be a concern, as is clients’ knowledge of prices, total cost and possible credit arrangements [9];

-

Acceptability as the relationship, between clients’ attitudes about personal and practice characteristics of existing providers including age, sex, location and type of facility or religious affiliation of the provider or facility, as well as provider attitudes about acceptable personal characteristics of clients, including ethnicity and source of payment [9].

In addition to the five accessibility dimensions, data extracted from the included publications consisted of study design, population, location, healthcare service type and main findings. These results were then combined into a single table.

Results

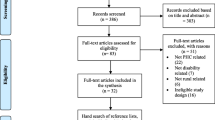

Figure 1 shows the PRISMA flowchart of paper inclusion for the review. Initially, 64 papers were identified in the review. Of these, 23 did not contain any information on the accessibility to health care services in Australia and were discarded. Table 1 provides a summary of the 41 publications included in the study. Eighteen studies were cross-sectional, three were longitudinal, ten were reviews, nine were editorials/commentaries and one was a case study. When looking at specific populations of older Australians included in the studies, six studies looked at migrants and refugees, seven investigated rural and remote populations and one exclusively studied Indigenous populations.

The results of the analysis of papers against Penchansky and Thomas’ five dimensions of accessibility [9] are shown in Table 2. Each of the dimensions of accessibility were represented in the review with 22 papers identifying issues of acceptability, 17 papers availability, 16 papers accessibility, 12 papers affordability and 6 papers accommodation. Of note is that 22 papers out of the 41 papers reviewed described more than one dimension of accessibility.

Discussion

This review has highlighted a number of factors affecting older Australians’ access to health services. Penchansky and Thomas’ dimensions of accessibility have provided a good working framework to organise the issues [9].

Availability

The availability of health services was often reported as an uneven distribution of health services not only in terms of spatial distribution but also with regards to the type of services offered for continuity of care [10]. For instance, there was an undersupply of many health services in both urban and rural areas, particularly the latter. Many older Australians were found to need to travel to services or wait for health professionals to visit. Of concern, an undersupply of acute and subacute hospital services was commonly reported [11] and, to a lesser extent, access to aged care services.

Another barrier to older Australians accessing health services was the lack of knowledge of what services were available and where to access them [12]. This barrier was not only experienced by patients and their families but also by health professionals and other service providers [12]. As well as knowing what services are available, access to health services was found to be initiated through a referral from a general practitioner (GP) [12], with many services not taking on patients without one, therefore creating a barrier for collaborative care.

Accessibility

This review has also identified a number of geographic accessibility issues facing older Australians accessing health services, particularly due to low workforce numbers, a lack of services and poor infrastructure [13]. Geographic accessibility to health services is a multifaceted issue for older Australians with transport to cover the geographic distance to health services posing multiple barriers for older people [14]. Older people with no transport are reliant on either family members or other forms of transport to access services [15]. The unreliable and/or non-existent public transport in many areas limits access to services [12]. Those that do drive prefer to drive at certain times and shorter distances, with preferences not to drive in heavy traffic or late in the day limiting their availability to accept appointments offered outside of their referred times [16].

As well as the direct issues associated with transport for older Australians accessing health services, there are boarder travel issues for many. The financial burden of travel can be significant for those travelling long distances especially when accommodation is required [17]. Fear of travel can be a concern for older Australians which includes fear of leaving home and family support networks [17].

E-health was seen within the literature as an alternative to traveling long distances to access health services. E-health was discussed as a way of enabling older people to access health care within their local area and therefore reducing the travel costs and the physical and practical inconveniences associated with having to travel to services [17].

Accommodation

This review also found that a lack of services, long waiting times and difficulties in getting an appointment with GPs and specialist health professionals were significant barriers for older people [18]. This is particularly an issue in rural areas where there is a lack of workforce due to government policy and difficulties in attracting families to rural areas limiting services [13]. Many health services are at capacity and after-hours appointments are limited or not available [12]. This is an issue when GPs act as a gateway to other health services.

Affordability

Penchansky and Thomas define affordability as the relationship between the prices of services and providers’ insurance or deposit requirements and the client’s income, ability to pay and existing health insurance [9]. Client perception of worth relative to total cost may be a concern, as is clients’ knowledge of prices, total cost and possible credit arrangements.

Older Australians often bare a larger financial burden than younger Australians due to the management of multiple chronic conditions and being reliant on a reduced fixed income [19]. However, the Medicare System in Australia provides free access to public hospital services and pays a scheduled amount for private medical services and ancillary health services [19]. The Pharmaceutical Benefits Schedule (PBS) subsidises the cost of pharmaceuticals to all Australians with the highest subsidies going to those on low incomes [20]. Both of these schemes aid in the affordability of health care for older Australians; however, many health professionals charge gap payments which make services less affordable. This review found that although Australians are able to claim five annual allied health service visits through Medicare when managed by their GP, many older Australians with ongoing health issues, five annual consultations were insufficient to enable effective management and active participation in self-care, productivity and leisure tasks and roles [21]. The current disability support system in Australia was described in the literature as underfunded, unfair, fragmented and inefficient [21]. E-health was reported in the literature as being a cost-effective method to deliver health services and remote monitoring in rural and remote areas [17].

Acceptability

Penchansky and Thomas define acceptability as the relationship, between clients’ attitudes about personal and practice characteristics of existing providers including age, sex, location and type of facility or religious affiliation of the provider or facility, as well as provider attitudes about acceptable personal characteristics of clients, including ethnicity and source of payment [9].

The literature review has highlighted that patient perceptions on the separation of physical and mental health service provision is an issue with the lack of collaboration between health services resulting in people with complex interconnecting physical and mental health problems having difficulties accessing services for an appropriate continuum of care [12]. There is also a need for services to be not only clinical but also broader in nature to include social support, informal and in-home services [22].

Health care for older people from ethnic minorities is seen as challenging because they tend to have a higher prevalence of chronic and disabling disease, and there is limited knowledge of their health care needs. The literature review has identified that older patients from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds are not a homogenous group and that this in itself creates many challenges for delivering appropriate models of health care through health services which fit their specific cultural needs [23]. Health care for older people from ethnic minorities can be challenging due to knowledge, attitudes, beliefs and health-seeking behaviours [24]. Central to older people accessing health care is the role of the family, duty and respect for parents and older people, religion, feelings of shame when receiving care from a non-family member, gender sensitivity and the difficulties of combining western health practices with their traditional health practices [14, 24,25,26].

Limited proficiency in English is frequently cited as the most problematic factor for the ethnic elderly in accessing mental health and other aged care services [27]. This is not only a problem for recently arrived elderly migrants, but also for many who came to Australia in the post-World War II migration boom [27]. While many older patients from ethnic backgrounds prefer to use family members as mediators and interpreters when dealing with health services, this often conflicts with organisational patient privacy policies [28].

The findings from this review have important implications for both service providers and health care policy makers. Australia is in the midst of a major health and aged care reform, and knowledge of older adults’ accessibility to healthcare services can better position health, aged and social care services to tackle future challenges expected from population ageing. For instance, identifying specific accessibility issues to care services and why these accessibility issues are occurring can inform health resource allocation decisions made by state and federal health departments; identifying locations for future health services, new mobile services, telehealth and other improvable components such as opening hours and costs of services are important factors that should be considered.

Results from this review are also relevant to older adults themselves. Now and into the future, the care needs of older adults need to be tailored to the individual beliefs, priorities and preferences of older adults. Consideration of these factors will enhance health service accessibility and, in turn, improve both service integration and outcomes of care.

Conclusion

The literature review has identified that currently older Australians face a number of accessibility issues when accessing health care services within Australia. With the increase in the number of older Australians and their preferred choice to age in place, health service planning will need to become more patient-centred. The literature review has highlighted the contribution of factors to health service accessibility that varies according to an older person’s geographical local, their accessibility to transport and their level of multi-morbidity and cultural background. Understanding the three important dimensions to ageing-in-place, the home the older person resides in, the community the person interacts within and the services and support that are available to them [29], will need to shape current and future health service models.

Limitations

This review identified issues facing older Australians accessing health services. Although the database search was comprehensive, it was limited to English-language papers published in scientific journals located by Academic Premier. Grey literature was also not searched, which may have provided an additional insight into issues affecting the health service accessibility of older adults. A further limitation of this review is that the majority of included publications were either cross-sectional or opinion pieces. Whilst these were informative, it is recommended that additional longitudinal study of healthcare accessibility for older Australians be performed as a means to further elucidate the issues underlying healthcare accessibility. Moreover, although there were several studies of older migrants/refugees identified in our review, there was a distinct lack of studies looking at the healthcare accessibility of Indigenous older Australians. Thus, given the large Indigenous gap in both health and life expectancy in Australia [1], it is recommended that further studies investigate healthcare accessibility issues of older Indigenous Australians.

References

Swan W. Australia to 2050: future challenges’ commonwealth of Australia. Canberra: Barton Australian Capital Territory; 2010. ISBN 978-0-642-74576-7

Australian Bureau of Statistics. 4430.0—disability, ageing and carers, Australia: summary of findings. Canberra: ACT; 2015.

Hugo G, 2010. “Demographic change and liveability panel report”, in a sustainable population strategy for Australia, Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities. Australian Government Commonwealth of Australia, ACT Canberra.

Armstrong BK, Gillespie JA, Leeder SR, Rubin GL, Russell LM. Challenges in health and health care for Australia. Med J Aust. 2007;187(9):485–9.

World Health Organisation. World health report on ageing and health. Geneva: WHO Press, World Health Organisation; 2015.

Weston R, Qu L, Soriano G, " The Changing Shape of Australia's Population". Australian Family Briefing, Australian Institute of Family Studies, No.10 September 2001.

National Research Council (2001) Preparing for an aging world: the case for cross-national research, panel on a research agenda and new data for an aging world, Committee on Population and Committee on National Statistics, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Victorian Government. Improving care for older people a policy for health services. Melbourne: Continuing Care Section, Programs Branch, Metropolitan Health and Aged Care Services Division Victorian Government Department of Human Services; 2003.

Penchansky R, Thomas JW. The concept of access: definition and relationship to consumer satisfaction. Med Care. 1981;19(2):127–40.

Giles LC, Halbert JA, Gray LC, Cameron ID, Crotty M. The distribution of health services for older people in Australia: where does transition care fit? Aust Health Rev. 2009;33(4):572–82.

Davis J, Morgans A, Stewart J. Developing an Australian health and aged care research agenda: a systematic review of evidence at the subacute interface. Aust Health Rev. 2016;40:420–7. https://doi.org/10.1071/AH15005

Muir-Cochrane E, O’Kane D, Barkway P, Oster C, Fuller J. Service provision for older people with mental health problems in a rural area of Australia. Aging and Mental Health. 2014;18(6):759–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2013.878307

Dellemain J, Warburton J. Case management in rural Australia: arguments for improved practice understandings. Aust Soc Work. 2013;66(2):297–310. https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2012.675345

Drummond PD, Mizan A, Brocx K, Wright B. Barriers to accessing health care services for West African refugee women living in Western Australia. Health Care Women Int. 2011;32:206–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/07399332.2010.529216.

Hurley C, Panagiotopoulos G, Tsianikas M, Newman L, Walker R. Access and acceptability of community-based services for older Greek migrants in Australia: user and provider perspectives. Health Soc Care Commun. 2013;21(2):140–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12000.

Greaves M, Rogers-Clark C. The experience of socially isolated older people in accessing and navigating the health care system. Aust J Adv Nurs. 2009;27(2):5–11.

Banbury A, Roots A, Nancarrow S. Rapid review of applications of E-health and remote monitoring for rural residents. Aust J Rural Health. 2014;22:211–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajr.12127.

Lowthian JA, Smith C, Stoelwinder JU, Smit DV, McNeil JJ, Cameron PA. Why older patients of lower clinical urgency choose to attend the emergency department. Intern Med J. 2012; https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1445-5994.2012.02842.x.

Jeon YH, Black A, Govett J, Yen L, McRae I. Private health insurance and quality of life: perspectives of older Australians with multiple chronic conditions. Aust J Prim Health. 2012;18:212–9. https://doi.org/10.1071/PY11059

Anderson I, Whyte JD. Australian federalism and aboriginal health. Aust Aborig Stud. 2006;2:5–16.

Tabrizi JS, O'Rourke PK, Wilson AJ, Coyne ET. Clinical care and delivery service quality for type 2 diabetes in Australia: the patient perspective. Diabet Med. 2008;25:612–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-5491.2008.02420.x.

Walker C. Multiple conditions: exploring literature from the consumer perspective in Australia. Health Expect. 2012;18:166–76.

Hughes M. The productivity commission inquiry into aged care: a critical review. Aust Soc Work. 2011;64(4):526–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2011.621084

Al Abed NA, Davidson PM, Hickman LD. Healthcare needs of older Arab migrants: a systematic review. J Clin Nurs. 2013;23:1770–84. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.12476.

Lau R, O’Connor M. Behind the rhetoric: is palliative care equitably available for all? Contemp Nurse. 2012;43(1):56–63.

Tang J, Ryburn B, Doyle C, Wells Y. The psychology of respite care for people with dementia in Australia. Aust Psychol. 2011;46:183–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-9544.2010.00005.x.

Hassett A, George K, Harrigan S. Admissions of elderly patients from English-speaking and non-English-speaking backgrounds to an inpatient psychogeriatric unit. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1999;33:576–82.

Wark S, Hussain R, Edwards H. Assisting individuals ageing with learning disability: support worker perspectives. Tizard Learn Disability Rev. 2015;20(4):213–22. https://doi.org/10.1108/TLDR-02-2015-0008.

Feist H, Parker K, Howard N, Hugo G. New technologies: their potential role in linking rural older people to community. Int J Emerg Tech Soc. 2010;8(2):68–84.

Al Abed NA, Hickman L, Jackson D, DiGiacomo M, Davidson PM. Older Arab migrants in Australia: between the hammer of prejudice and the anvil of social isolation. Contemp Nurse. 2014;46(2):259–62.

Allen J, Inder KJ, Lewin TJ, Attia J, Kelly BJ. Social support and age influence distress outcomes differentially across urban, regional and remote Australia: an exploratory study. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:928.

Aoun SM, Skett K. A longitudinal study of end-of-life preferences of terminally-ill people who live alone. Health Soc Care Commun. 2013;21(5):530–5. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12039.

Bhar S. Poor psych services for aged care residents. Aust Nurs Midwifery J. 2016;24(4):29.

Brand C, Hunter D, Hinman R, March L, Osborne R, Bennell K. Improving care for people with osteoarthritis of the hip and knee: how has national policy for osteoarthritis been translated into service models in Australia? Int J Rheum Dis. 2011;14:181–90.

Cornell V. Community health, aged care and a stable home: an important relationship. Aust Nurs Midwifery J. 2016;23(7):43.

Evans D. The provision of health and social care services for older people by respite providers. Contemp Nurse. 2013;45(2):255–63.

Harris MF, Powell Davies PG, Fanaian M, Zwar NA, Liaw ST. Access to same day, next day and after-hours appointments: the views of Australian general practitioners. Aust Health Rev. 2012;36:325–30. https://doi.org/10.1071/AH11080

Hiruy K, Mwanri L. End-of-life experiences and expectations of Africans in Australia: cultural implications for palliative and hospice care. Nurs Ethics. 2014;21(2):187–97.

Hughes M. Older lesbians and gays accessing health and aged-care services. Aust Soc Work. 2007;60(2):197–209. https://doi.org/10.1080/03124070701323824.

Jiwa M, Asteljoki S, Pagey G. What factors will impact on the adoption of digital technology to access general practitioners in Australia? Qual Prim Care. 2013;21:261–5.

Joo JY, Huber DL. An integrative review of nurse-led community-based case management effectiveness. Int Nurs Rev. 2014;61(1):14–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/inr.12068.

Lowe J. Yentl Resurgat: inadequate management of cardiovascular risk in women. Intern Med J. 2011;41 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1445-5994.2011.02581.x.

Moorin R, Gibson D, Bulsara CE, Holman CDJ. Challenging the perceptions of cancer service provision for the disadvantaged: evaluating utilisation of cancer support services in Western Australia. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20:1687–97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-011-1262-1.

Rosenwax L, Spilsbury K, Arendts G, McNamara B, Semmens J. Community-based palliative care is associated with reduced emergency department use by people with dementia in their last year of life: a retrospective cohort study. Palliat Med. 2015;29(8):727–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216315576309.

Russi M. NDIS and occupational therapy: compatible in intention and purpose from the consumer perspective. Aust Occup Ther J. 2014;61:364–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/1440-1630.12138.

Schofield T. Gender and health inequalities: what are they and what can we do about them? Aust J Soc Issues. 2008;43(1):139-57.

Tilse C. Cash, customers, and care: the experience and meaning of differential payment for high care places in aged care facilities. Aust J Soc Issues. 2002;37(4):383–96.

Warburton J, Cowan S, Savy P, MacPhee F. Toward the development of a more integrated aged care assessment process for rural older Australians: practitioners’ perspectives. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2015;58(5):503–20.

Ward PR, Javanparast S, Wilson C. Equity of colorectal cancer screening: which groups have inequitable participation and what can we do about it? Aust J Prim Health. 2011;17:334–46. https://doi.org/10.1071/PY11055

Wark S, Canon-Vanry M, Ryan P, Hussain R, Knox M, Edwards M, Parmenter M, Parmenter T, Janicki M, Leggatt-Cook C. Ageing-related experiences of adults with learning disability resident in rural areas: one Australian perspective. Br J Learn Disabil. 2015;43:293–301.

Funding

ED is funded by a National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Early Career Fellowship (grant number 1112672).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DvG undertook the initial review gathering the publications to be reviewed. Both DvG and ED reviewed all of the publications and analysed them against the five dimensions of accessibility. DvG wrote the first draft of the introduction and methods sections. ED wrote the first draft of the discussion section. Both DvG and ED revised the second draft and both contributed to the final manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Competing interests

All authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

van Gaans, D., Dent, E. Issues of accessibility to health services by older Australians: a review. Public Health Rev 39, 20 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40985-018-0097-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40985-018-0097-4