Abstract

Formulaic sequences comprise a large body of language and their mastery is supposed to be a key determiner of language proficiency. However, despite their significance in language learning, they are seldom taught in any principled manner in language classrooms and their correct and appropriate use remains a particular challenge to language learners, even at advanced levels. To address this issue, the current study investigated the relationship between knowledge of formulaic sequences and language proficiency as well as the most efficient method of instructing formulaic sequences. Participants of the study were 42 Japanese learners of English as a foreign language at three different levels of language proficiency (low intermediate, intermediate, and high intermediate) at the intensive English program of a university in Japan. Instruments used for data collection consisted of a reading comprehension book containing a large number of formulaic sequences for intervention sessions and an oral-production discourse completion task adopted from Bardovi-Harlig et al. (2015) for testing knowledge of formulaic sequences as pre-test, post-test, and follow-up test. The study followed an experimental design by administering the pre-test, randomly assigning participants to two equal groups of ‘focus on form’ and ‘focus on forms’, conducting intervention sessions for four consecutive weeks (following the noticing, retrieving, and generating process) to teach formulaic sequences to both groups but at different levels of explicitness, administering the post-test immediately following intervention, and administering the follow-up test a period of time following the post-test. The findings of the study revealed that knowledge of formulaic sequences is a strong predictor of language proficiency and both ‘focus on form’ and ‘focus on forms’ methods of instructing formulaic sequences are equally effective in developing and retaining knowledge of formulaic sequences. The pedagogical implications of the findings suggested incorporating knowledge of formulaic sequences in every language instruction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The term “formulaic sequence” encompasses a continuous or discontinuous sequence of words, with a syntactically and semantically well-formed structure, which can be stored and produced holistically (Qi & Ding, 2011). It is a broad term that covers various lexical units including idioms, proverbs, collocations, lexical bundles, and conventionalized expressions (Schmitt & Carter, 2004). Research suggests that at least one-third to one-half of language is composed of formulaic sequences (Conklin & Schmitt, 2008; Conklin & Schmitt, 2012). Erman and Warren (2000) calculated that formulaic sequences of various classes constituted 58.6% of the spoken English discourse they analyzed and 52.3% of the written discourse. Foster (2001) had raters look for formulaic sequences in transcripts of unplanned English native speech, and these raters judged that 32.3% of the speech was made up of formulaic sequences. The ubiquity of formulaic sequences in language indicates that their mastery is a key determiner of language proficiency (Wray & Perkins, 2000; Bybee, 2002; Wray, 2002; Biber et al., 2004; DeCock, 2004; Wray, 2008; Barfield & Gyllstad, 2009; McGuire, 2009; Schmitt, 2010; Meunier, 2012). A number of researchers also claim that appropriate use of formulaic sequences can help language learners reach a higher level of language proficiency not only in terms of fluency, but also in terms of range of expression and accuracy (e.g., Wood, 2006; Boers et al., 2006; Wood, 2010; Stengers et al., 2010; Stengers et al., 2011; Boers & Lindstromberg, 2012; Henriksen, 2013; Peters, 2014).

However, formulaic sequences are seldom taught in any principled manner in language classrooms (AlAli & Schmitt, 2012) and despite their prevalence and importance in everyday life, they are often the last hurdle that advanced language learners have to overcome to achieve native-like proficiency (Gouverneur, 2008). As a result, the correct and appropriate use of formulaic sequences remains a particular challenge to language learners, even at advanced levels (Laufer & Waldman, 2011) and language learners, even at higher levels of language proficiency, know and use fewer formulaic sequences than native speakers (Foster, 2001). Therefore, considering the significance of possessing a high command of formulaic sequences in achieving native-like proficiency, many scholars in the field of linguistics advocate the incorporation of target language formulaic sequences in target language instruction (e.g., Jones & Haywood, 2004; Boers et al., 2006; Ellis et al., 2008; Boers & Lindstromberg, 2009; Wood, 2009; Wood, 2010; Hatami, 2015).

There are generally two methods of incorporating formulaic sequences, referred to as form-focused instruction methods, in language instruction: ‘focus on form’ and ‘focus on forms’. ‘Focus on form’ occurs in the context of meaning-focused language use, and procedures intended to induce ‘focus on form’ avoid overt targeting of specific forms either by teachers or by materials writers. In contrast, so-called ‘focus on forms’ procedures target particular forms largely in isolation from meaningful context (Lindstromberg et al., 2016). For over a generation there have been disagreements over adopting the instruction procedure which brings about the best outcome. The advocates of ‘focus on form’ instruction method claim that classroom time is clearly too limited to explicitly teach more than a fraction of the vast number of formulaic sequences in a language. Therefore, they recommend devoting class time to activities that raise language learners’ awareness of the ubiquity of formulaic sequences rather than spending time on the direct teaching of particular formulaic sequences. In this view, it is hoped that an enhanced awareness of formulaicity will foster independent learning because language learners will be more inclined to notice formulaic sequences in the samples of target language they engage with outside the language classroom. In addition, it is hoped that language learners will be more attentive to information about the syntagmatic behavior of words they look up in a dictionary (Boers & Lindstromberg, 2012). However, the advocates of ‘focus on forms’ instruction method believe that formulaic sequences should be taught explicitly because, despite their frequency in various contexts, they seem to be complex in nature (Cortes, 2004; Jones & Haywood, 2004; Boers & Lindstromberg, 2009). In other words, formulaic sequences may be either entirely transparent and, hence, pass unnoticed by language learners, or highly opaque and thus evoke a kind of mental burden on the part of language learners who will, in turn, try to disregard them in context (Boers & Lindstromberg, 2009). More importantly, through focused instruction, language learners will probably get the chance to rehearse and internalize this language phenomenon and ultimately utilize it in their language production (Wood, 2009).

Given the significance of knowledge of formulaic sequences in developing language proficiency on one hand and the significance of adopting the right method of instruction to develop knowledge of formulaic sequences in language learners on the other hand, the current study seeks to investigate the actual relationship between knowledge of formulaic sequences and language proficiency, the general effect of instruction on developing knowledge of formulaic sequences, and the most efficient method of instructing formulaic sequences. In this respect, the research questions to be addressed in the study are:

Is there any significant relationship between knowledge of formulaic sequences and language proficiency?

To what extent does form-focused instruction develop knowledge of formulaic sequences?

Do ‘focus on form’ and ‘focus on forms’ instructions equally develop knowledge of formulaic sequences?

Accordingly, the null hypotheses are:

There is no significant relationship between knowledge of formulaic sequences and language proficiency.

Form-focused instruction has no effect on developing knowledge of formulaic sequences.

‘Focus on form’ and ‘focus on forms’ instructions do not equally develop knowledge of formulaic sequences.

Literature review

Relationship between Knowledge of Formulaic Sequences and Language Proficiency

The review of literature in the areas of formulaic sequences and language proficiency during the past decade shows inconsistency in the findings of the studies conducted over the relationship between knowledge of formulaic sequences and language proficiency. While some studies found that higher knowledge of formulaic sequences leads to higher level of language proficiency (e.g., Bardovi-Harlig et al., 2008; Qi & Ding, 2011; Rafieyan, 2018), some other studies found a slight or a lack of correlation between knowledge of formulaic sequences and language proficiency (e.g., Staples et al., 2013; Serrano et al., 2015).

In one of these studies, Bardovi-Harlig et al. (2008) investigated the production of a specific type of formulaic sequences referred to as conventional expressions by learners of different first language backgrounds at different levels of language proficiency, from low intermediate to low advanced, at the intensive English program of a university in the United States. Participants of their study consisted of 108 language learners from two main geographical regions, Persian Gulf and East Asia, with 55 and 53 language learners, respectively. The study employed a speech production task via a computer-delivered aural discourse completion task comprising two each of thanking, apology, and refusal scenarios. The comparison of multiple first languages showed that learners of various first languages often share production strategies. The comparison of different levels of language proficiency showed that language learners increase their use of conventional expressions at higher levels of language proficiency requiring both linguistic and sociopragmatic competence. These finings showed the strong positive relationship between knowledge of formulaic sequences and language proficiency.

In a study, which supported the findings obtained by Bardovi-Harlig et al. (2008), Qi and Ding (2011) explored whether there is any improvement in formulaic sequence use in terms of frequency, accuracy, and variation in Chinese learners of English as a foreign language between years One and Four or not. Data used in the study was derived from the Longitudinal Spoken English Corpus of Chinese Learners which contained transcriptions of audio recordings of Chinese learners of English as a foreign language on different topics collected twice a year from 2001 to 2004. The data were analyzed qualitatively and quantitatively. Qualitative analysis involved the examination of the use of a particular type of formulaic sequences. It also involved the examination of erroneous formulaic sequences together with the concordance lines in which they occurred in attempt to tease out the sources of errors. Quantitative analyses measured the frequency, accuracy, and variation of formulaic sequences when investigating the use of formulaic sequences in oral texts. The study revealed that language learners make progress in formulaic sequence use in speech over the years of their university study and the dimensions of frequency, accuracy, and variation indexing formulaic sequence performance underwent diversified developmental patterns.

In a similar vein, Rafieyan (2018) examined the relationship between knowledge of formulaic sequences and language proficiency. Participants of his study were 45 Japanese learners of English as a foreign language at three levels of the intensive English program of a university in Japan: low intermediate, intermediate, and high intermediate. Knowledge of formulaic sequences was assessed through an oral-production discourse completion task developed by Bardovi-Harlig et al. (2015). The analysis of Spearman rank-order correlation coefficient showed a strong positive relationship between language learners’ knowledge of formulaic sequences and their level of language proficiency.

The findings obtained in the study conducted by Staples et al. (2013), however, were not consistent with the findings obtained in the studies conducted by Bardovi-Harlig et al. (2008), Qi & Ding (2011), and Rafieyan (2018). In their study, Staples et al. (2013) investigated whether the frequency, function, and fixedness of lexical bundles used by learners of English as a foreign language in a controlled environment vary across proficiency levels or not. The study used the data from a corpus composed of written responses to items on the TOEFL iBT. The corpus was further subdivided into three proficiency levels of low, medium, and high based on a range of Education Testing Service (ETS) scores. Biber et al.’s (2004) taxonomy was used to identify lexical bundle functions. The results indicated that lower level language learners used more lexical bundles overall but also more lexical bundles identical to those in the prompts. In contrast, the functional analysis revealed a similar use of stance and discourse organizing lexical bundles across proficiency levels and very few referential lexical bundles used by any of the groups. In addition, there were few differences in fixed versus variable slot lexical bundles across proficiency levels. The findings revealed that knowledge of formulaic sequences is not a predictor of language proficiency.

In another study, which supported the findings by Staples et al. (2013), Serrano et al. (2015) investigated whether intensive exposure is more beneficial for lower proficient language learners, or whether a certain command of the target language is necessary before language learners can benefit from intensive exposure to the language. The participants in the study included 124 Spanish/Catalan learners of English as a foreign language at three different levels of proficiency: beginner, intermediate, and advanced. Language learners were enrolled in two program types: intensive and regular in which the methodological approach, textbooks, exams, and so on were the same for the intensive and the regular programs, the main difference for the two being time distribution. To examine language learners’ use of formulaic sequences, their target language performance was analyzed in an oral narrative based on a series of pictures. The results of the study revealed that concentrating time distribution of hours of language instruction fosters the acquisition of formulaic sequences under certain conditions. However, intensity was not equally beneficial for the acquisition of formulaic sequences at all proficiency levels: high proficient language learners did not seem to benefit from intensive instruction to the same extent as low proficient language learners. The findings suggested that a higher knowledge of formulaic sequences does not necessarily lead to a higher level of language proficiency.

Effect of form-focused instruction on the development of knowledge of formulaic sequences

Research on the effectiveness of instruction on the development of knowledge of formulaic sequences has attracted the attention of a considerable number of linguists for more than a decade. In this regard, researchers examined the effectiveness of different types of form-focused instructional methods ranging from implicit techniques of indirectly attracting language learners’ attention to target language forms using ‘focus on form’ procedures to explicit techniques of directly explaining target language forms using ‘focus on forms’ procedures. Although some of the researchers merely focused on the effectiveness of one of the form-focused instructional methods and others compared the effectiveness of different types of form-focused instructional procedures, they came up with varying findings: some researchers found ‘focus on form’ techniques more effective (e.g., Peters, 2012), some attested the superiority of ‘focus on forms’ techniques (e.g., Bardovi-Harlig et al., 2015; Peters & Pauwels, 2015; AlHassan & Wood, 2015), and some others revealed the effectiveness of both ‘focus on form’ and ‘focus on forms’ techniques of instructing formulaic sequences (e.g., Rafieyan et al., 2014; Rafieyan, 2017).

In one of these studies, Boers et al. (2006) investigated the effect of mastery of formulaic sequences on language learners’ fluency, range of expression, and accuracy in the language to be learned. Participants of their study consisted of two groups of students majoring in English at a college in Belgium: an experimental group and a control group. Both groups of language learners were exposed to the same authentic language input and their course materials were identical. However, the attention of language learners in the experimental condition was directed to common word combinations occurring in the texts using ‘focus on forms’ techniques whereas the attention of language learners in the control condition was given to individual words or grammar patterns. At the end of the course, language learners were interviewed. Two blind judges then assessed language learners’ oral proficiency taking into account fluency, range of expression, and accuracy. The use of formulaic sequences was shown to be especially beneficial to perceptions of language learners’ fluency and range of expression but the evidence for its positive influence on language learners’ perceived accuracy was found to be less convincing. The findings suggested that although ‘focus on forms’ instruction of formulaic sequences is influential in learning a wide range of expressions and developing fluency, it does not guarantee the accurate use of the obtained knowledge.

In another study which further explored the effectiveness of ‘focus on forms’ instruction method on the development of knowledge of formulaic sequences, Bardovi-Harlig et al. (2015) investigated the impact of ‘focus on forms’ instruction on the learning of formulaic sequences for use in academic discussion. The study implemented a pretest-intervention-posttest design with experimental and control groups. A total of 37 language learners participated in either the experimental or the control condition. The control group was merely included to gauge the influence of taking the test twice. The intervention for the experimental group consisted of four 50-min lessons, each lesson comprising three primary elements: noticing of expressions in context, explicit metapragmatic information concerning use, and opportunities for production. The instrument used for data collection was a computer-delivered oral-production test consisting of 30 items comprising 10 agreement, 10 disagreement, and 10 clarification scenarios. The results showed that production of both speech acts and targeted expressions increased significantly in the experimental condition, whereas the control group did not show significant change. The findings confirmed the effectiveness of ‘focus on forms’ instruction on the development of knowledge of formulaic sequences.

To further confirm the findings obtained by Bardovi-Harlig et al. (2015), Peters and Pauwels (2015) explored whether vocabulary-focused instruction, in which the formulaic sequences are the explicit focus of teaching, has the potential to boost language learners’ awareness and use of academic formulaic sequences or not. The participants in the study were 29 Dutch-speaking learners of English as a foreign language at a Flemish Dutch-medium university in Belgium. The intervention was organized in three consecutive weeks. The learning materials that were used in the intervention consisted of two types of activities: recognition activities and cued output activities. The activities were designed according to the principle of ‘focus on forms’ vocabulary instruction or explicit vocabulary learning. Three types of tests at different levels of sensitivity were developed: a recognition test, a cued output test, and a writing test. The three tests were used as pre-test and post-test. Finally, language learners’ end-of-year assignments were also analyzed in terms of the number of formulaic sequences used. The findings of the study suggested that explicit vocabulary-focused instruction of academic formulaic sequences has the potential to boost language learners’ awareness, cued output, and spontaneous use of formulaic sequences.

In a similar vein, AlHassan and Wood (2015) investigated the effectiveness of ‘focus on forms’ instruction of formulaic sequences in augmenting language learners’ academic writing skills. The pool of participants comprised 12 learners of English as a foreign language. The intervention involved explicit instructional approach to formulaic sequences based on consciousness-raising which consisted of a presentation stage followed by a practice stage. As for data collection, three timed paragraphs were elicited from language learners at three time periods: at the beginning of the study before any instruction (pre-test), at the end of the study (post-test), and fifteen to twenty days after the end of the training period (delayed post-test). At each stage of data collection, language learners were required to write a summary in response to the graphic prompt designed for data collection. The study demonstrated the effectiveness of ‘focus on forms’ instruction of formulaic sequences in motivating language learners to increasingly utilize this language phenomenon in their writing, in the successful acquisition and internalization of the formulaic sequences into language learners’ linguistic repertoires, and in fostering language learners’ ability to augment their written production with different types of formulaic sequences.

Moving away from merely focusing on effectiveness of explicit ‘focus on forms’ instruction, Peters (2012) explored the effect of two instructional interventions, directing language learners to pay explicit attention to unfamiliar formulaic sequences in a reading text (‘focus on forms’ instruction method) and prompting language learners to allocate attentional resources to unfamiliar formulaic sequences in a reading text by using bold typeface and underlining the target items (‘focus on form’ instruction method), on language learners’ form recall of single words and formulaic sequences. Twenty-eight freshman students of applied language studies at a Flemish institution of higher education took part in the study. The target items consisted of 12 single words (six in bold typeface/underlined and six not in bold typeface/not underlined) and 12 formulaic sequences (six in bold typeface/underlined and six not in bold typeface/not underlined). Language learners’ form recall of the 24 target items was measured via an immediate and delayed posttest, in which they had to supply the German translation of as many items as possible. The findings of the study suggested that although the explicit instructional method had an effect on the number of formulaic sequences that language learners wrote down on their vocabulary sheets, it did not induce the kind of processing that resulted in higher recall scores. The use of typographic salience, on the other hand, facilitated vocabulary learning because target items in bold typeface and underlined were not only written down more frequently in language learners’ notes, they were also recalled more often compared to target items not typographically enhanced. These findings suggested the superiority of ‘focus on form’ instruction method over ‘focus on forms’ instruction method.

To further explore the effectiveness of different form-focused methods of instruction, Rafieyan et al. (2014) conducted a study on a group of undergraduate learners of English as a foreign language at a university in Iran to compare the effect of ‘focus on form’ and ‘focus on forms’ methods of instruction on acquiring a particular type of formulaic sequences referred to as conventional expressions. The study followed an experimental design by assigning language learners to three groups including two experimental groups and one control group, conducting 8 intervention sessions, and administering a 32-item discourse completion task to assess their knowledge of formulaic sequences. Language learners in one of the experimental groups were taught formulaic sequences based on ‘focus on form’ method through watching videos and reading texts flooded with formulaic sequences. Language learners in the other experimental group were taught formulaic sequences based on ‘focus on forms’ method through metapragmatic explanations of formulaic sequences followed by role-plays. Language learners in the control group were merely taught the grammatical features of the language to be learned. The comparison of language learners’ performance in different instruction groups on the discourse completion task revealed that both ‘focus on form’ and ‘focus on forms’ methods of instruction were equally effective in developing language learners’ knowledge of formulaic sequences.

In another experiment, Rafieyan (2017) examined the short-term and long-term effects of ‘focus on form’ as compared to ‘focus on forms’ methods of instruction on the development of knowledge of formulaic sequences. Participants of the study consisted of two groups of learners of English as a foreign language at the intensive English program of a university in Japan: a ‘focus on form’ instruction group and a ‘focus on forms’ instruction group. For the ‘focus on form’ group, formulaic sequences were taught implicitly using typographic enhancement, disappearing text, and reading comprehension techniques. Instruction for ‘focus on forms’ group was based on explicit techniques of reading comprehension, role-play, and defining of formulaic sequences. The instruments used in the study consisted of a reading comprehension book used as instructional materials as well as three sets of recognition tests and cued output tests with the same level of difficulty used as pre-test, post-test, and follow-up test. The study followed an experimental design with a pre-test one week prior to intervention, four weeks of intervention, a post-test one week following intervention, and a follow-up test ten weeks following the post-test. The analysis of mixed between-within subjects analysis of variance revealed that both ‘focus on form’ and ‘focus on forms’ methods of instructing formulaic sequences are equally effective for immediate and long-term goals.

Methods

Participants

Participants of the study were selected based on convenience sampling. They were all learners of English at researcher’s institute at the time of data collection. The sample comprised 42 Japanese learners of English as a foreign language at the intensive English program of International College of Liberal Arts at Yamanashi Gakuin University. Among the participants, 18 were males and 24 were females. Their ages ranged from 18 to 20, with the mean age of 19.4. The participants were at three different levels of language proficiency based on an institutional TOEFL ITP placement test: low intermediate (TOEFL scores of ranging from 451 to 500; 15 participants), intermediate (TOEFL scores of ranging from 501 to 550; 12 participants), and high intermediate (TOEFL scores of ranging from 551 to 600; 15 participants). The 42 participants formed two equal groups of 21 for the experiment. According to the comparison of TOEFL scores of participants in the two groups, using independent-samples t-test, there was no significant difference between the levels of language proficiency for both groups (p > 0.05). Also, based on the data collected from a background information questionnaire, none of the participants had the experience of living in a native English-speaking country. However, they were in touch with native English-speaking exchange students at the university and the majority of their teachers were from native English-speaking countries. Therefore, they were all equally exposed to target language and culture.

Instruments

Instructional Materials

Materials used for instruction were from Strategic Reading 2 written by Jack C. Richards and Samuela Eckstut-Didier published by Cambridge University Press. Strategic Reading is a three-level series designed to develop reading, vocabulary-building, and critical-thinking skills. The Strategic Reading 2 is an intermediate reading skills text for adult and young-adult learners of English as a second or foreign language. Strategic Reading 2 is designed to build the reading skills and vocabulary that language learners need to achieve academic success. The book contains 16 units on contemporary themes. Each unit contains three multiple-genre readings adapted from authentic sources such as newspapers, magazines, books, and websites. Units open by introducing new vocabulary and asking students thought-provoking questions related to the unit theme. On the page opposite the readings are exercises that develop language learner interest in the theme, provide practice in a variety of text-appropriate reading skills, and offer opportunities for discussion and/or writing. The final page features vocabulary expansion activities and suggestions for extension activities, which can be completed either inside or outside the classroom. Being at the proper level for participants, being up to date, and focusing on vocabulary activities made this book suitable for intervention sessions of the current study.

Instruments for Pre-test, Post-test, and Follow-up test

To test language learners’ knowledge of formulaic sequences, an oral-production discourse completion task developed by Bardovi-Harlig et al. (2015) was adopted. The discourse completion task included 30 scenarios. The 30 scenarios consisted of 10 agreement, 10 disagreement, and 10 clarification (5 self-clarification and 5 other-clarification) scenarios. This is a type of oral-production discourse completion task that has been used with increasing frequency as a measure of oral production in pragmatics (Nickels, 2006; Schauer, 2007; Bardovi-Harlig, 2009; Bardovi-Harlig et al., 2015). Each item on the discourse completion task started with a brief description of the topic and then for agreements and disagreements gave language learners a specific opinion. Language learners read the descriptions and their position. After language learners heard and read the setting and their position, they heard a classmate’s turn to which they responded. The narrator and the classmate alternated between a male and female voice so that language learners could easily distinguish the classmate’s turn from the narrator’s turn. The same discourse completion task was used immediately before intervention as pre-test, immediately after intervention as post-test, and a period of time after intervention as follow-up test. However, following Taguchi (2008a), Taguchi (2008b), Riddifford and Joe (2010), and Riddiford and Holmes (2015), each time the discourse completion task was administered, the order of scenarios was changed to avoid practice effect.

Procedure

The study was conducted in the spring semester of the academic year 2017. The study followed an experimental design with pre-test, intervention, post-test, and follow-up test. At the beginning of the semester, the pre-test discourse completion task was administered to all language learners participating in the study. Language learners were told that the test was merely administered to verify their familiarity with academic English. Following the completion of the discourse completion task, language learners were randomly assigned to two equal groups: a ‘focus on form’ group (21 participants) and a ‘focus on forms’ group (21 participants). The week following the pre-test, intervention started. A native-English teacher, who was a full-time TESOL teacher at International College of Liberal Arts at Yamanashi Gakuin University, conducted the instruction for both groups. The intervention consisted of eight sessions which were held twice weekly for four consecutive weeks, each session lasting 75 min. For each session, one unit of Strategic Reading 2 was taught, covering eight units of the book in general. The intervention followed the noticing, retrieving, and generating process to teach formulaic sequences for both groups but at different levels of explicitness. According to Nation (2001), the first major process to encourage the learning of a lexical item is noticing, that is, directing language learners’ attention toward a formulaic sequence and making them aware of its usefulness. The next major process that may help with learning and remembering vocabulary is retrieval, that is, providing language learners with repeated opportunities to retrieve the lexical item that is to be acquired. The third and most effective process for establishing vocabulary knowledge is generation, which “occurs when previously met words are subsequently met or used in ways that differ from the previous meeting with the word” (Nation, 2001, p. 68).

In the ‘focus on form’ instruction condition, the noticing phase involved directing language learners’ attention toward formulaic sequences included in the reading passages through highlighting them. In this phase, language learners received copies of the reading passages in which formulaic sequences were written in boldface type. Language learners were asked to read the text as many times as they needed and answer reading comprehension and vocabulary exercises that followed each unit. They were allowed to check their dictionaries or ask for the meaning of unfamiliar words or expressions. In the retrieving phase, following Nation and Newton (2009), the disappearing text technique was used. In this technique, a passage of approximately 50 to 60 words containing a number of formulaic sequences was selected and was written on the board, and a language learner was asked to read it aloud. Then some of the formulaic sequences were deleted and another language learner was asked to read the passage aloud, supplying the missing formulaic sequences as he or she read. Then more formulaic sequences were deleted, and this continued until there were no formulaic sequences at all on the board and the language learners were repeating the passage from their memory. In the generating phase, excerpts from other reading sources in which the same formulaic sequences taught during the session had been used in a different context and again in boldface type were given to language learners. Language learners were then asked to read the excerpts and answer the comprehension and vocabulary exercises that followed them.

In the ‘focus on forms’ instruction condition, the noticing phase involved asking language learners to read the passage as many times they needed and answer the comprehension and vocabulary exercises that followed the unit. In this phase, language learners were asked to try to guess the meaning of formulaic sequences from context and/or have the sequences explained to them. In the retrieving phase, an approach, known as role-play or exchange structure, was used. In this approach, language learners were given a context or scenario and were asked to orally exchange information using formulaic sequences. For example, one language learner could extend an invitation (e.g., Would you like to come to my birthday party on Friday?), and the other language learner accepted (e.g., Yes, thanks a lot) or refused the invitation (e.g., I’d love to, but …). In the generating phase, language learners were provided with definitions for formulaic sequences using example sentences which were different from those encountered in the textual input. Language learners were then asked to isolate formulaic sequences in sentences and create new texts around them.

Then, respectively one week following intervention in week six and at the end of semester in week 16, the post-test and follow-up test discourse completion tasks were administered to language learners in both groups.

Data Analysis

The responses to the scenarios on the pre-, post-, and follow-up discourse completion tasks were transcribed by the researcher. The responses were then coded by two native-English speakers. If a language learner produced the targeted speech act appropriately, the response received a score of 1 point. However, if the targeted speech act was not produced appropriately, it earned no point. There were 10 points possible for expressions that occurred in the context of agreements, 10 points possible for expressions that occurred in the context of disagreements, and 5 points for each of self- and other-clarifications. As there were 30 items on the discourse completion task, each language learner could get a score ranging from 0 to 30. The number of items receiving 1 point for a targeted expression were calculated for each language learner for agreements, disagreements, and self- and other-clarifications. Then, the mean score and standard deviation of the performance of language learners in each level of language proficiency (low intermediate, intermediate, high intermediate) and in each instruction group (‘focus on form’ group and ‘focus on forms’ group) on each test (pre-test, post-test, follow-up test) was calculated. The inter-rater reliability for the ratings of the responses to the discourse completion pre-test, post-test, and follow-up test, as indicated by Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient (r), were respectively r = 0.88, r = 0.92, and r = 0.90.

The relationship between language learners’ knowledge of formulaic sequences and their language proficiency was assessed through correlating language learners’ performance on the pre-test discourse completion task, in which language learners’ awareness of target language formulaic sequences had not been developed through intervention yet, and their level of language proficiency using Spearman rank-order correlation coefficient (rho). Spearman rank-order correlation coefficient (rho) is used to test for a rank order relationship between two quantitative variables when concerned that one or both variables is ordinal (rather than interval) and/or not normally distributed or when the sample size is small (Gravetter & Wallnau, 2013). The value of Spearman rank-order correlation coefficient can range from − 1 to + 1. The positive and negative signs out the front indicate whether there is a positive correlation (as one variable increases, the other variable increases as well) or a negative correlation (as one variable increases, the other variable decreases). The size of the value, regardless of the sign, provides an indication of the strength of the relationship. Values of closer to + 1 or − 1 are indicative of higher correlation between the two variables, whereas values of closer to 0 are indicative of a lower correlation (Pallant, 2013). Cohen (1988) suggests a set of guidelines to interpret the values between 0 and 1. The guidelines, which have been presented in Table 1, apply whether or not there is a positive or negative sign out the front of the correlation value (r value).

The squared correlation (r2), called the coefficient of determination, was then used to measure the proportion of variability in knowledge of formulaic sequences that can be determined from its relationship with language proficiency. Squared correlation would give a value ranging from 0 to 1. Cohen (1988) has also suggested a set of guidelines to interpret the values of squared correlation. The criterion for interpreting the value of squared correlation (r2), as proposed by Cohen (1988), has been presented in Table 2.

Mixed between-within subjects analysis of variance was then employed to determine whether the different types of instruction had made any learning gains in language learners from pre-test to post-test and whether they sustained the gains after a period of time. Mixed between-within subjects analysis of variance allows combining between-subjects and within-subjects variables in one analysis (Pallant, 2013). In this respect, both the effectiveness of intervention in general (within-subjects effect) and the effectiveness of specific type of intervention, that is, ‘focus on form’ instruction and ‘focus on forms’ instruction (between-subjects effect) was considered. Partial eta squared was then used to examine the level of effect of intervention for both within-subjects and between-subjects categories. Partial eta squared can range from 0 to 1 and represents the proportion of variance in the dependent variable (acquisition of formulaic sequences) that is explained by the independent variable (type of intervention) (Pallant, 2013). Cohen (1988) proposed a set of guidelines to interpret the values of partial eta squared. The guidelines for interpreting the values of eta squared, as proposed by Cohen (1988), are presented in Table 3. Finally, the graphical presentation of the performance of language learners in both ‘focus on form’ group and ‘focus on forms’ group on the pre-test, post-test, and follow-up test was provided.

Findings and Discussion

Findings

Relationship between Knowledge of Formulaic Sequences and Language Proficiency.

Table 4 presents the descriptive analysis of knowledge of formulaic sequences for language learners both at each proficiency level and in general. As the data presented in the table shows, knowledge of formulaic sequences increases with level of language proficiency: language learners at low intermediate level displayed the lowest knowledge of formulaic sequences (mean score: 6.67), language learners at intermediate level outperformed the low intermediate ones but their performance was not as good as the high intermediate counterparts (mean score: 11.25), and language learners at high intermediate level had the highest performance (mean score: 15.20). However, the mean performance of language learners in all proficiency levels in general was not remarkable (mean score: 11.02). This indicates that, regardless of level of language proficiency, language learners do not possess a high command of formulaic sequences in general.

Table 5 presents the results of Spearman rank-order correlation coefficient (rho) analysis for language learners’ knowledge of formulaic sequences (their performance on pre-test discourse completion task) and their level of language proficiency. The first thing to consider in correlation analysis is the direction of the relationship between the two variables (knowledge of formulaic sequences and language proficiency). The data shows that there is a positive relationship between the two variables, that is, as knowledge of formulaic sequences increases so too does level of language proficiency. The second thing to consider in correlation analysis is the size of the value of the correlation coefficient. This value indicates the strength of the relationship between the two variables (knowledge of formulaic sequences and language proficiency). The value of correlation coefficient obtained in the analysis of Spearman rank-order correlation coefficient (rho) is 0.82 which according to the guidelines proposed by Cohen (1988) to interpret the values of correlation coefficient suggests quite a strong relationship between knowledge of formulaic sequences and language proficiency.

To get an idea of how much variance the two variables (knowledge of formulaic sequences and language proficiency) share, the coefficient of determination was calculated. This can be obtained by squaring the correlation value. The coefficient of determination for the obtained correlation analysis is r2 = (0.82)2 = 0.67 which according to the guidelines proposed by Cohen (1988) to interpret the values of coefficient of determination suggests a very large correlation coefficient. To convert the value of coefficient of determination to ‘percentage of variance’, it was multiplied by 100, that is, r2 = (0.82)2 × 100 = 67. This suggests that knowledge of formulaic sequences helps to explain 67% of the variance in language learners’ language proficiency. The performance of language learners at different language proficiency levels has been depicted in Fig. 1.

Effect of Form-Focused Instruction on the Development of Knowledge of Formulaic Sequences

Table 6 presents the results of the descriptive analysis of performance of language learners on pre-test, post-test, and follow-up test. The descriptive analysis presented in the table consists of the number of participants for each type of instruction as well as the mean and standard deviation obtained for the performance of each group of participants on pre-test, post-test, and follow-up test. According to the descriptive analysis of the data, the mean score for the performance of language learners in both ‘focus on form’ and ‘focus on forms’ groups on the knowledge of formulaic sequences enhanced in post-test and follow-up test. However, although the mean score obtained by language learners in the ‘focus on forms’ group was slightly higher than the mean score obtained by language learners in the ‘focus on form’ group immediately following the intervention, the pattern was reversed within a period of ten weeks following the intervention. The mean score by itself, however, does not show whether the difference among the three tests and between the two groups is considered significant or not. To determine whether the difference among mean scores obtained by the two groups over the three tests is significantly different from one another or not, the results of the analysis of mixed between-within subjects analysis of variance need to be observed.

Table 7 presents the results of the main effect for within-subjects variable (Test: pre-test, post-test, follow-up test). To explore the main effect for within-subjects variable, the value of Wilks’ Lambda and the associated probability value given in the column labeled Significance (Sig.) needs to be considered. All of the multivariate tests yield the same result. However, the most commonly reported statistic is Wilks’ Lambda (Pallant, 2013). A significance value of above 0.05 (p > 0.05) for Wilks’ Lambda indicates a non-significant effect whereas a significance value of equal to or less than 0.05 (p ≤ 0.05) is indicative of a significant effect (Gravetter & Wallnau, 2013). In the data obtained in the current study, the value for Wilks’ Lambda for Test is 0.02, with a significance value of 0.00 (which really means p < 0.05). Because the probability value is less than 0.05, there is a statistically significant effect for Test. This suggests that there was a change in knowledge of formulaic sequences across the three different tests. The main effect for Test was significant.

Although a statistically significant difference among language learners’ knowledge of formulaic sequences on different tests (pre-test, post-test, and follow-up test) was found, the effect size of this result also needs to be considered to be able to determine the exact size of this difference. In this regard, the value of interest is partial eta squared. The value of partial eta squared obtained for Test in this study is 0.98. Using the commonly used guidelines proposed by Cohen (1988), this result suggests a very large effect size. Expressed as a percentage, 98% of variance in the change in language learners’ knowledge of formulaic sequences is explained by the treatment they received between the three tests.

Now that the within-subjects effects have been explored, the main effect for between-subjects variable (type of instruction: ‘focus on form’ instruction versus ‘focus on forms’ instruction) needs to be considered. The results that need to be considered are in Table 8. In this respect, the significance value across the row labeled Group (variable name for the type of instruction) should be considered. A significance value of above 0.05 (p > 0.05) for Group indicates a non-significant effect whereas a significance value of equal to or less than 0.05 (p ≤ 0.05) is indicative of a significant effect (Gravetter & Wallnau, 2013). In the data obtained in the current study, the value for Group is 0.70. This is more than the alpha level of 0.05, so the main effect for Group is non-significant. There was no significant difference in knowledge of formulaic sequences for the two groups (those who were instructed based on ‘focus on form’ method and those who were instructed based on ‘focus on forms’ method).

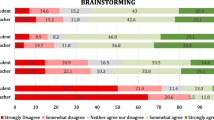

The graphical presentation of language learners’ knowledge of formulaic sequences in both ‘focus on form’ and ‘focus on forms’ groups in pre-test, post-test, and follow-up test has been depicted in Fig. 2. As Fig. 2 shows, although language learners in ‘focus on forms’ group had a slightly better performance than their counterparts in ‘focus on form’ group immediately following the intervention and the pattern was reversed within a period of time following the intervention, the difference was not statistically significant and language learners in both groups, generally, exhibited a significant improvement in knowledge of formulaic sequences following intervention and maintained the obtained knowledge after ten weeks following the intervention.

Discussion

The study found that there is a strong positive relationship between language learners’ knowledge of formulaic sequences and their level of language proficiency. Language learners who possessed a higher level of language proficiency demonstrated a higher level of knowledge of formulaic sequences than language learners who possessed a lower level of language proficiency. The study also found that not only form-focused instruction is generally very effective in both developing knowledge of formulaic sequences and sustaining the obtained knowledge in language learners, but also both ‘focus on form’ and ‘focus on forms’ methods of instructing formulaic sequences are equally effective for immediate and long-term goals. Language learners in both ‘focus on form’ and ‘focus on forms’ groups demonstrated a significant progress in knowledge of formulaic sequences immediately following a four-week intervention period and managed to retain the obtain knowledge for ten weeks following the intervention. Therefore, all three null hypotheses of the study which state that there is no significant relationship between knowledge of formulaic sequences and language proficiency, form-focused instruction has no effect on developing knowledge of formulaic sequences, and ‘focus on form’ and ‘focus on forms’ instructions do not equally develop knowledge of formulaic sequences are rejected.

The strong positive correlation between knowledge of formulaic sequences and language proficiency can be explained through the fact that normal discourse, both written and spoken, contains large percentage of formulaic sequences, making up between one third and one half of discourse (Conklin & Schmitt, 2008; Conklin & Schmitt, 2012) and more exposure to target language input, through reading of and listening to materials, leads language learners to encounter more formulaic sequences. Research (Raichle, 1998; McCrone, 1999) has shown that once the brain is familiar with a linguistic task, it is able to bypass the processing route that was used to learn it (Wray & Perkins, 2000). Consequently, the brain would make use of relatively abundant resources by storing frequently occurring formulaic sequences which could then be easily retrieved and used without the need to compose them online through word selection and grammatical sequencing (Pawley & Syder, 1983). This helps language users who possess a higher knowledge of formulaic sequences to be more proficient.

Although language learners who had a higher knowledge of formulaic sequences were more proficient users of the language to be learned, they were not at native-like level and did not show optimal performance on the test. This can be explained though the fact that in cases where high proficient language learners do seem to have mastered a repertoire that resembles that of native speakers in terms of width, this does not necessarily mean their knowledge of the formulaic sequences therein is similar to that of native speakers in terms of depth. One reason is that their intuitions about the commonness of formulaic sequences and about the commonness of their usage patterns are sanctioned and are likely to be less reliable. Furthermore, high proficient language learners may have good receptive knowledge of a range of formulaic sequences, but still fail to fully deploy this resource and resort to nonnative-like formulaic sequences copied from first language (Boers & Lindstromberg, 2012).

Width refers to the quantity of formulaic sequences that the language learner is familiar with, without specifying how familiar (e.g., language learners may recognize a given word string as a recurring sequence, but they may not use it themselves or may not fully appreciate its pragmatic function). Depth refers to the degree of proceduralization of knowledge as well as to knowledge of the distributional properties of a given formulaic sequence in usage (i.e., how common it is, in what co-text and context it is most likely to occur, and—in case it is a variable expression—what its most common variants are) (Boers & Lindstromberg, 2012).

When formulaic sequences are well entrenched in memory, co-text is imbued with predictability (e.g., Last but not …). This may also work in reverse in a way that enables something partly heard to be reconstructed post facto (e.g., Did Michael Jackson really […] suicide?). All this eases processing so that attention can be allocated to parts of the discourse that are less formulaic and therefore less predictable. In fact, only when a sequence is deeply entrenched in a language user’s long-term memory, it qualifies as truly formulaic for that user. Word strings that bring the aforesaid processing advantages to a native speaker may not (yet) do so for language learners. Although high proficient language learners recognize and use many standardized word strings that are formulaic for native speakers, they may not process these strings the same way as native speakers do (Boers & Lindstromberg, 2012).

According to Wray and Perkins’s (2000) model of processing formulaic sequences, unlike native speakers who are likely to have stored common word sequences holistically, that is, as single unanalyzed chunks which can be retrieved from memory as prefabricated units and as a result bypass the need to assemble the sequences word by word, adult language learners are less likely to have stored conventional word strings holistically. Accordingly, the most likely processing benefit that formulaic sequences confer on a language learner is that particular formulaic sequences may be encountered often enough that the associations between the component words become so strong that, on meeting or recalling part of the string, the language learner will recall the rest (Boers & Lindstromberg, 2012).

These findings are consistent with the findings obtained in the study conducted by Bardovi-Harlig et al. (2008) who found that knowledge of formulaic sequences, regardless of language-cultural background, plays a significant role in determining the proficiency level of language learners. The findings of the current study are also in line with the findings obtained in the study conducted by Qi and Ding (2011) who found that more proficient language learners possess a higher inventory of formulaic sequence knowledge. The findings obtained in the current study further support the findings obtained in the study conducted by Rafieyan (2018) who found a strong positive relationship between language learners’ knowledge of formulaic sequences and their level of language proficiency. The findings obtained in the study, however, do not support the findings obtained in the studies conducted by Staples et al. (2013) and Serrano et al. (2015) who found a lack of correlation between knowledge of formulaic sequences and language proficiency.

The equal effectiveness of ‘focus on form’ and ‘focus on forms’ methods in terms of both short-term and long-term effects can be explained through Noticing Hypothesis. Noticing Hypothesis introduced by Schmidt (1990) states that “people learn about the things that they attend to and do not learn much about the things they do not attend to” (Schmidt, 2001:30). This hypothesis emphasizes that in order for the input to become intake, the detection of input in the form of awareness and attention is necessary (Schmidt, 1995). Not all input has equal value and only that input which is noticed then becomes available for intake and effective processing (Schmidt, 1990; Schmidt, 2001). Intake is part of the input which is being paid attention to and is taken into short-term memory and consequently is integrated into the interlanguage, a language independent from both the language learner’s native language and the target language (Selinker, 1972).

The three stages of noticing, retrieving, and generating formulaic sequences adopted for instructing formulaic sequences during the intervention period of the study, despite using different procedures for ‘focus on form’ and ‘focus on forms’ groups, were equally effective in language learners’ noticing of target language forms, helping target language input to turn into intake and processed effectively. In this respect, not only language learners’ attention was directed toward target language forms (noticing phase), but also language learners were provided with repeated opportunities to retrieve the target language formulaic sequences (retrieval phase) and use them in ways that differed from the ways they were used previously (generating phase) (Hatami, 2015). This helped to guarantee the acquisition of formulaic sequences that were noticed.

Although the formulaic sequences used to assess language learners’ knowledge of formulaic sequences differed from the ones used during intervention, it can be assumed that the awareness of formulaic sequences developed in them through noticing, retrieving, and generating techniques helped them to consciously look up the meaning of formulaic sequences they encountered in the course of their language studies, leading them to the acquisition of many other formulaic sequences which they were not taught. This has also most probably been the reason to maintain and increase their knowledge of target language formulaic sequences even months following the intervention period. This supports the ideas that devoting class time to activities that raise language learners’ awareness of ubiquity of formulaic sequences is more effective than spending time on teaching particular formulaic sequences (Lewis, 1993). In this respect, an enhanced awareness of target language formulaic sequences fosters independent learning because not only language learners will be more inclined to notice formulaic sequences in the samples of target language they engage with outside the language classroom but also they will be more attentive to information about the syntagmatic behavior of words they look up in a dictionary (Boers & Lindstromberg, 2012).

These findings are in line with the findings obtained in the studies conducted by Boers et al. (2006), Bardovi-Harlig et al. (2015), Peters and Pauwels (2015), and AlHassan and Wood (2015) who assessed the effectiveness of form-focused instruction in developing knowledge of formulaic sequences using explicit ‘focus on forms’ techniques and found form-focused instruction effective in developing knowledge of formulaic sequences. These findings also support the findings obtained in the studies conducted by Rafieyan et al. (2014) and Rafieyan (2017) who found both ‘focus on form’ and ‘focus on forms’ methods of instruction equally effective in developing language learners’ knowledge of formulaic sequences. These findings, however, are not consistent with the findings obtained in the study by Peters (2012) who found the superiority of ‘focus on form’ method over ‘focus on forms’ method in developing language learners’ knowledge of formulaic sequences.

Conclusion

The study investigated the relationship between knowledge of formulaic sequences and language proficiency and compared the immediate and long-term effects of two methods of form-focused instruction including ‘focus on form’ and ‘focus on forms’ on the development of knowledge of formulaic sequences. The findings of the study revealed that knowledge of formulaic sequences is a strong predictor of language proficiency and both ‘focus on form’ and ‘focus on forms’ methods of instructing formulaic sequences are equally effective in the development and retention of knowledge of formulaic sequences. Language learners participating in the study who were at higher levels of language proficiency demonstrated a higher knowledge of formulaic sequences than language learners who were at lower levels of language proficiency and language learners in both ‘focus on form’ and ‘focus on forms’ groups, despite receiving different types of instruction, managed to equally develop and retain their knowledge of formulaic sequences following intervention. Therefore, instruction of formulaic sequences, using either ‘focus on form’ method or ‘focus on forms’ method, should be an indispensable component of every language classroom (Rafieyan, 2015; Rafieyan, 2016a; Rafieyan, 2016b).

The study was limited in some ways, however. First of all, the intervention was conducted for only four weeks. Although a four-week period might be enough to develop awareness of the distinction between formulaic and nonformulaic sequences, it is not long enough to develop knowledge of formulaic sequences in language learners. Secondly, the retention of the acquired knowledge through different methods of instruction was assessed only after two months. A two-month period is not considered long enough to determine the level of sustainability of the obtained knowledge for the two different instructional procedures as some instructional procedures especially those which use implicit techniques require a long time for the actual outcomes to appear. Finally, the study did not involve a comparison with the effect of instruction during an educational sojourn to investigate the role of learning environment in the development of knowledge of formulaic sequences. Therefore, future studies are recommended to include three groups of ‘focus on form’, ‘focus on forms’, and ‘study-abroad’, extend the intervention for the whole semester by incorporating target forms in regular language learning classrooms, and assess the retention of the instruction in intervals of six and twelve months.

References

AlAli, F. A., & Schmitt, N. (2012). Teaching formulaic sequences: The same as or different from teaching single words? TESOL Journal, 3(2), 153–180 https://doi.org/10.1002/tesj.13.

AlHassan, L., & Wood, D. (2015). The effectiveness of focused instruction of formulaic sequences in augmenting L2 learners’ academic writing skills: A quantitative research study. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 17, 51–62 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2015.02.001.

Bardovi-Harlig, K. (2009). Conventional expressions as a Pragmalinguistic resource: Recognition and production of conventional expressions in L2 pragmatics. Language Learning, 59(4), 755–795 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9922.2009.00525.x.

Bardovi-Harlig, K., Mossman, S., & Vellenga, H. E. (2015). The effect of instruction on pragmatic routines in academic discussion. Language Teaching Research, 19(3), 324–350 https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168814541739.

Bardovi-Harlig, K., Rose, M., & Nickels, E. L. (2008). The use of conventional expressions of thanking, apologizing, and refusing (selected proceedings of the 2007 second language research forum, ed. Melissa Bowles et al., 113–130). Somerville, MA: Cascadilla Proceedings Project.

Barfield, A., & Gyllstad, H. (2009). Researching collocations in another language: Multiple interpretations. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230245327.

Biber, D., Conrad, S., & Cortes, V. (2004). If you look at ...: Lexical bundles in university teaching and textbooks. Applied Linguistics, 25(3), 371–405 https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/25.3.371.

Boers, F., Eyckmans, J., Kappel, J., Stengers, H., & Demecheleer, M. (2006). Formulaic sequences and perceived oral proficiency: Putting a lexical approach to the test. Language Teaching Research, 10(3), 245–261 https://doi.org/10.1191/1362168806lr195oa.

Boers, F., & Lindstromberg, S. (2009). Optimizing a lexical approach to instructed second language acquisition. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230245006.

Boers, F., & Lindstromberg, S. (2012). Experimental and intervention studies on formulaic sequences in a second language. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 32, 83–110 https://doi.org/10.1017/S0267190512000050.

Bybee, J. (2002). Phonological evidence for exemplar storage of multi-word sequences. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 24(2), 215–221 https://doi.org/10.1017/S0272263102002061.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Conklin, K., & Schmitt, N. (2008). Formulaic sequences: Are they processed more quickly than nonformulaic language by native and nonnative speakers? Applied Linguistics, 29(1), 72–89 https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amm022.

Conklin, K., & Schmitt, N. (2012). The processing of formulaic language. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 32, 45–61 https://doi.org/10.1017/S0267190512000074.

Cortes, V. (2004). Lexical bundles in published and student disciplinary writing: Examples from history and biology. English for Specific Purposes, 23(4), 397–423 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esp.2003.12.001.

DeCock, S. (2004). Preferred sequences of words in NS and NNS speech. Belgian Journal of English Language and Literatures (BELL). New Series, 2, 225–246.

Ellis, N. C., Simpson-Vlach, R., & Maynard, C. (2008). Formulaic language in native and second language speakers: Psycholinguistics, Corpus linguistics, and TESOL. TESOL Quarterly, 42(3), 375–396 https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1545-7249.2008.tb00137.x.

Erman, B., & Warren, B. (2000). The idiom principle and the open choice principle. Text, 20(1), 29–62 https://doi.org/10.1515/text.1.2000.20.1.29.

Foster, P. (2001). Rules and routines: A consideration of their role in the task-based language production of native and non-native speakers. In M. Bygate, P. Skehan, & M. Swain (Eds.), Researching pedagogical tasks: Second language learning, teaching and testing (pp. 75–93). Harlow, UK: Longman.

Gouverneur, C. (2008). The phraseological patterns of high-frequency verbs in advanced English for general purposes: A Corpus-driven approach to EFL textbook analysis. In F. Meunier & S. Granger (Eds.), Phraseology in foreign language learning and teaching (pp. 223–243). Amsterdam: John Benjamins https://doi.org/10.1075/z.138.17gou.

Gravetter, F. J., & Wallnau, L. B. (2013). Statistics for the behavioral sciences. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing.

Hatami, S. (2015). Teaching formulaic sequences in the ESL classroom. TESOL Journal, 6(1), 112–129 https://doi.org/10.1002/tesj.143.

Henriksen, B. (2013). Research on L2 learners’ collocational competence and development: A progress report. In C. Bardel, C. Lindqvist, & B. Laufer (Eds.), L2 vocabulary acquisition, knowledge and use: New perspectives on assessment and Corpus analysis (pp. 29–56). Amsterdam: Eurosla Monographs Series 2.

Jones, M., & Haywood, S. (2004). Facilitating the Acquisition of Formulaic Sequences: An exploratory study in an EAP context. In N. Schmitt (Ed.), Formulaic Sequences (pp. 269–292). Amsterdam: John Benjamins https://doi.org/10.1075/lllt.9.14jon.

Laufer, B., & Waldman, T. (2011). Verb-noun collocations in second language writing: A Corpus analysis of learners’ English. Language Learning, 61(2), 647–672 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9922.2010.00621.x.

Lewis, M. (1993). The lexical approach: The state of ELT and a way forward. Hove, England: Language Teaching Publications.

Lindstromberg, S., Eyckmans, J., & Connabeer, R. (2016). A modified Dictogloss for helping learners remember L2 academic English formulaic sequences for use in later writing. English for Specific Purposes, 41, 12–21 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esp.2015.08.002.

McCrone, J. (1999). States of mind. New Scientist, 2178 (20 March), 30–33.

McGuire, M. (2009). Formulaic sequences in English conversation: Improving spoken fluency in non-native speakers, MA thesis. Denton: University of North Texas.

Meunier, F. (2012). Formulaic language and language teaching. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 32(1), 111–129. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0267190512000128.

Nation, I. S. P. (2001). Learning vocabulary in another language. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139524759.

Nation, I. S. P., & Newton, J. (2009). Teaching ESL listening and speaking. New York, NY: Routledge.

Nickels, E. L. (2006). Interlanguage pragmatics and the effects of setting. In K. Bardovi-Harlig, C. Félix-Brasdefer, & A. Omar (Eds.), Pragmatics and language learning (Vol. 11, pp. 253–280). Honolulu: National Foreign Language Resource Center, University of Hawaii.

Pallant, J. (2013). SPSS survival manual: A step by step guide to data analysis using SPSS program (5th ed.). Australia: Allen & Unwin.

Pawley, A., & Syder, F. H. (1983). Two puzzles for linguistic theory: Nativelike selection and nativelike fluency. In J. C. Richards & R. W. Schmidt (Eds.), Language and communication (pp. 191–226). London: Longman.

Peters, E. (2012). Learning German formulaic sequences: The effect of two attention-drawing techniques. The Language Learning Journal, 40(1), 65–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/09571736.2012.658224.

Peters, E. (2014). The effects of repetition and time of post-test administration on EFL learners’ form recall of single words and collocations. Language Teaching Research, 18(1), 75–94. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168813505384.

Peters, E., & Pauwels, P. (2015). Learning academic formulaic sequences. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 20, 28–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2015.04.002.

Qi, Y., & Ding, Y. (2011). Use of formulaic sequences in monologues of Chinese EFL learners. System, 39(2), 164–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2011.02.003.

Rafieyan, V. (2015). Effect of National Cultural Distance as predictor of pragmatic competence on writing proficiency. Research on Humanities and Social Sciences, 5(18), 122–129.

Rafieyan, V. (2016a). Effect of pragmatic instruction versus educational sojourn on knowledge of conventional expressions. International Journal of Learning and Development, 6(2), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.5296/ijld.v6i2.9403.

Rafieyan, V. (2016b). Effect of ‘focus on form’ versus ‘focus on forms’ pragmatic instruction on development of pragmatic comprehension and production. Journal of Education and Practice, 7(20), 41–48.

Rafieyan, V. (2017). Effectiveness of ‘focus on form’ versus ‘focus on forms’ instruction on the development of knowledge of formulaic sequences. Journal of Literature, Languages and Linguistics, 38, 45–55.

Rafieyan, V. (2018). Knowledge of formulaic sequences as a predictor of language proficiency. International Journal of Applied Linguistics & English Literature, 7(2), 64–69. https://doi.org/10.7575/aiac.ijalel.v.7n.2p.64.

Rafieyan, V., Sharafi-Nejad, M., & Lin, S. E. (2014). Effect of form-focused pragmatic instruction on production of conventional expressions. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 4(8), 1586–1592. https://doi.org/10.4304/tpls.4.8.1586-1592.

Raichle, M. E. (1998). The neural correlates of consciousness: An analysis of cognitive skill learning. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, Series B, 353, 1889–1901. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.1998.0341.

Riddiford, N., & Holmes, J. (2015). Assisting the development of Sociopragmatic skills: Negotiating refusals at work. System, 48, 129–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2014.09.010.

Riddiford, N., & Joe, A. (2010). Tracking the development of Sociopragmatic skills. TESOL Quarterly, 44(1), 195–205. https://doi.org/10.5054/tq.2010.215252.

Schauer, G. A. (2007). Finding the right words in the study abroad context: The development of German learners’ use of external modifiers in English. Intercultural Pragmatics, 4(2), 193–220. https://doi.org/10.1515/IP.2007.011.

Schmidt, R. W. (1990). The role of consciousness in second language learning. Applied Linguistics, 11(2), 129–158. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/11.2.129.

Schmidt, R. W. (1995). Consciousness and foreign language learning: A tutorial on the role of attention and awareness in learning. In R. W. Schmidt (Ed.), Attention and awareness in foreign language learning (Technical Report No. 9 (pp. 1–63). Honolulu: University of Hawaii.

Schmidt, R. W. (2001). Attention. In P. Robinson (Ed.), Cognition and second language instruction (pp. 3–32). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139524780.003.

Schmitt, N. (2010). Researching vocabulary: A vocabulary research manual. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230293977.

Schmitt, N., & Carter, R. (2004). Formulaic sequences in action: An introduction. In N. Schmitt (Ed.), Formulaic sequences: Acquisition, processing and use (pp. 1–22). Amsterdam: John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/lllt.9.

Selinker, L. (1972). Interlanguage. International Review of Applied Linguistics, 10(2), 209–230. https://doi.org/10.1515/iral.1972.10.1-4.209.

Serrano, R., Stengers, H., & Housen, A. (2015). Acquisition of Formulaic Sequences in intensive and regular EFL Programmes. Language Teaching Research, 19(1), 89–106. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168814541748.

Staples, S., Egbert, J., Biber, D., & McClair, A. (2013). Formulaic sequences and EAP writing development: Lexical bundles in the TOEFL iBT writing section. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 12(3), 214–225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2013.05.002.

Stengers, H., Boers, F., Housen, A., & Eyckmans, J. (2010). Does ‘Chunking’ Foster Chunk-Uptake? In S. De Knop, F. Boers, & A. De Rycker (Eds.), Fostering language teaching efficiency through cognitive linguistics (pp. 99–117). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110245837.99.

Stengers, H., Boers, F., Housen, A., & Eyckmans, J. (2011). Formulaic sequences and L2 oral proficiency: Does the type of target language influence the association? International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching (IRAL), 49(4), 321–343. https://doi.org/10.1515/iral.2011.017.

Taguchi, N. (2008a). Cognition, language contact, and the development of pragmatic comprehension in a study-abroad context. Language Learning, 58(1), 33–71. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9922.2007.00434.x.

Taguchi, N. (2008b). The role of learning environment in the development of pragmatic comprehension: A comparison of gains between EFL and ESL learners. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 30(4), 423–452. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0272263108080716.

Wood, D. (2006). Uses and functions of formulaic sequences in second-language speech: An exploration of the foundations of fluency. The Canadian Modern Language Review, 63(1), 13–33.

Wood, D. (2009). Effects of focused instruction of formulaic sequences on fluent expression in second language narratives: A case study. Canadian Journal of Applied Linguistics, 12(1), 39–57.

Wood, D. (2010). Formulaic language and second language speech fluency: Background, evidence and classroom applications. New York, NY: Continuum International Publishing Group.

Wray, A. (2002). Formulaic language and the lexicon. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511519772.

Wray, A. (2008). Formulaic language: Pushing the boundaries. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Wray, A., & Perkins, M. R. (2000). The functions of formulaic language: An integrated model. Language & Communication, 20(1), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0271-5309(99)00015-4.

Funding

The study did not receive any funding.

Availability of data and materials

Please contact author for data requests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The author read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares that he has no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Rafieyan, V. Role of knowledge of formulaic sequences in language proficiency: significance and ideal method of instruction. Asian. J. Second. Foreign. Lang. Educ. 3, 9 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40862-018-0050-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40862-018-0050-6