Abstract

Background

So far, the effect of graphene oxide (GO) and reduced graphene oxide (rGO) in rubber matrix has not been well established.

Methods

The effects of graphene oxide (GO) and reduced graphene oxide (rGO) on the physical properties of polar acrylonitrile-butadiene rubber (NBR) and non-polar Ethylene-propylene-diene terpolymer rubber (EPDM) matrix have been investigated and their properties compared. NBR vulcanizates exhibited higher cure rates compared to the EPDM systems.

Results

Effective dispersion of the nanosheets within the different matrices was observed to be a reason for the improvement in properties, but the effective nanosheets-matrix interactions played a key role in reinforcing action. This was noticeable in the various properties (crosslinking density, tensile properties, and dynamical mechanical analysis) evaluated. Typically, the polar NBR matrix was observed to show about 461 and 405% higher interactions parameter with GO and rGO fillers (loaded from 0.1~1phr) than composites of EPDM based on Kraus model.

Conclusions

While this present work has confirmed the significance of considering the polarities of graphene sheets or derivative graphene (GSD) and their respective polymers matrices for effective property enhancement for specific applications, it has also demonstrated the future prospects of rubber-graphene nanocomposites for several applications which include structural, barrier, and dielectric energy storage materials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The research of graphene and/or derivative graphene sheets (GSD)-reinforced rubber nanocomposites for technological applications such as; strain-sensitive materials, thermal insulators, gas barrier materials, and oil/gas sealing etc. is a fascinating area, which is still under vigorous study.

The GSD material has gained attention in polymer technology because of its unique properties and its ability to disperse and bond well in polymer matrices (Bai et al. 2011; Bora et al.2013). For instance, a defect-free graphene has shown superior properties like high surface area (theoretical limit: ~2630 m2 g−1), excellent thermal conductivity (5000 Wm−1 K−1), amazing mechanical strength (ultimate strength ~130 GPa, and Young modulus of ~1 TPa) with very high electrical conductivity (6000 Scm−1). These unique properties of graphene have increased the potentials of rubber materials for advanced applications (Blake et al. 2007; Novoselov et al. 2004; Qiu et al. 2011).

One of the easily observable advantage of GSD over conventional fillers is that, GSD requires only small concentration (≤ 0.1 phr) for reinforcing virgin elastomers for elastomeric/GSD composites with substantial properties (Boland et al. 2014; Tan et al.2008; Tseng et al. 2012; Wei, et al. 2014), whereas the conventional fillers such as; carbon blacks (CB), and nanoclays requires enormous loading level (≥ 5~20phr) to attain equivalent properties as the case of GSD based systems (Choi et al. 2005; Hong et al. 2007).

Compared to the conventional composites such as rubber-clays, rubber-carbon blacks, and rubber-nanotubes etc., further works on elastomer-GSD composites will be needed to fully understand these materials and their potential applications. Also, the results reported on elastomer-GSD composites by majority of researchers are controversial and mostly not consistent (Bai et al.2011; Hernández et al. 2012; Li et al. 2013). For example, a recent study by Li et al. (2013) and Hernández et al.(2012) have confirmed that graphene sheets (GS) have shown a strong interaction with natural rubber. Contrary to this, Bai et al.(2011), Li, et al. (2011), Kang et al.(2014) and Allahbakhsh, et al.(2013) have all emphasized that the numerous oxygen moieties (–OH, –O–C=O, and C–O–C etc) contained in graphene oxide (GO) sheets makes it compatible with rubber matrix, should the resulting properties be compared with those of reduced graphene oxide (rGO), which is a modified GS.

In addition to this, the effect of GO/rGO/GS in polar and nonpolar rubber matrix has not been well established. That is, GO/rGO and other derivatives graphenes reinforced with various elastomers with different polarities have shown different curing with varied physico-mechanical properties (Allahbakhsh et al. 2013; Mensah, et al. 2014; Mensah et al. 2015; Varghese et al. 2013). The influence of the corrugating/wrinkling structural texture of the graphene sheet on rubber matrix has shown different findings on resulting properties of the composites by different researchers. Li et al. (2012) had investigated the tribological properties of NBR-GO composites prepared by solution mixing method. The morphological studies of the composites confirmed the presence of wrinkled GO sheets which were coated with NBR molecules. These composites had shown high wear resistance than the unfilled NBR compounds. Adversely, wrinkled graphene nano platelets (GnPs) have shown weak interfacial interactions with EPDM matrix (Valentini et al. 2014). Therefore, a study that explores the preparation and properties of GO/rGO in a polar (NBR) and non-polar (EPDM) matrix will help to understand the state of GO and rGO in rubber matrix of different polarities.

The physico-mechanical properties of NBR-GO and NBR-rGO nanocomposite has been reported in our earlier work (Mensah et al. 2014). In this present work, the effect of GO/rGO in EPDM was explored and compared with those of NBR-GO/rGO nanocomposites. Herein, we prepare nanocomposites of EPDM-GO/rGO and NBR/GO/rGO separately by using a combined method of solution and solid mixing. The various properties, such as; vulcanization, mechanical, thermal and dielectric spectroscopy were examined. In the end, it has been observed that the GO and rGO generally offer more reinforcing advantage in a polar rubber matrix than a non-polar rubber type.

Methods/Experimental

Materials and sample preparation

Materials

Acrylonitrile-butadiene rubbers having acrylonitrile content between 20 and 30% (NBR, KNB 25LM™, Kumho Petrochemical Co., Korea) and Ethylene-propylene-diene monomer (EPDM) (Vistalon 7500; ethylene content 55.5%, ENB content 5.7%) supplied by the Kumho Petrochemical Co., Korea were used as a base rubbers. The synthesis of GO and rGO was done as per our previous work (Mensah et al. 2015).

Preparation of nanocomposites

There is no any literature available which adopt solvent mixing method to process EPDM-based nanocomposites; hence this work is the first of its kind. The preparation of the non-polar EPDM compounds (EPDM, EPDM-GO and EPDM-rGO) is as shown in Fig. 1(i-iv);

The EPDM was dissolved in toluene under 60 °C temperature for ~12 h (see Fig. 1(i)). The GO and rGO were also dispersed in toluene via prolonged ultranisonication for ~2 h. The GO/toluene and rGO/toluene solutions were mixed with EPDM/toluene mixture separately. The mixtures were stirred vigorously by magnetic stirrer at 60 °C for 12 h until homogenous composites solutions were observed (see Fig. 1(ii) for the case of rGO/EPDM). Later, an acetone was gradually added to these mixtures while still stirring with a spatula to avoid phase separation. This resulted in coagulation of the EPDM-GO and EPDM-rGO compounds. A typical coagulation process and resulting composite of EPDM-rGO is shown in Fig. 1(iii) and iv respectively. The sample obtained; EPDM and EPDM-GO/rGO were then oven dried at 80 °C until the weight of the solid mass remained the same and free from trapped air.

Conventional sulfur curing additives were dispersed in EPDM, EPDM/GO, and EPDM/rGO compounds before sheeting out in two-roll mill (Model: DS-1500R, Withlab Co. Ltd., Korea). For comparison of properties, NBR-GO and NBR-RGO nanocomposites were also prepared as per our earlier work (Mensah et al. 2014; Mensah et al. 2015). The nanocomposite formulations and the codes of the NBR and EPDM based compounds are presented in Table 1.

A cure rheometer analysis was carried on the samples to determine the optimum cure condition. The compounds were cured for an optimized time interval on a hot press machine (Caver WMV50H, USA) maintained at 160 °C with applied pressure of ~11 MPa. The specimens of cured nanocomposites were cut into standard shapes for carrying out various tests including tensile, equilibrium swelling, tensile, and dielectric measurements etc.

Characterization

Vulcanization property

The cure property was measured at 160 °C by a cure rheometer (ODR 2000, Alpha Technologies, USA). The cure properties including onset of cure time (ts2), optimum cure time (t90), cure rate index (CRI = 100/(t90-ts2)), maximum (MH) and minimum torque (ML), and change in torque (∆M = MH-ML) were obtained and reported.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

The morphologies EPDM-GO/rGO compounds were cryogenically fractured initially. In order to observe GO and rGO and their interactions with the various rubbers, the fractured compounds surfaces were compressed for 96 h using the device in Fig. 2. After removal of strain, the specimen were coated by platinum via sputtering and then observed with field emission SEM (JEOL, JSM 599, Japan). The coating and observation process lasted for ~20 min. This method had previously been adopted to study the morphologies of NBR-GO/rGO composites (Mensah et al. 2014; Mensah et al. 2015).

Crosslinking density

The chemical crosslinking density by swelling experiments of vulcanized compounds were performed by equilibrating NBR and NBR-GO/rGO nanocomposites in methyl ethyl ketone (MEK) (molar volume (ν1) of 89.6 mL/mol) whereas EPDM and EPDM-GO/rGO nanocomposites in Toluene (molar volume 106.3 mL/mol) for 72 h. The experiment was carried out at room temperature. Initially the sample dimension were estimated and weighed as W i . They were then fully immersed into the solutions, after immersion, the soaked sample were wiped and weighed to obtain swollen weights W s . The samples were dried in an oven at a temperature of 50 °C for 24 h. They were then allowed to cool in open air for about 6 h. Later the dried weights of the samples were recorded as W dr . The liquid absorbed (Wa) given by W s -W i and the dried weights were used to calculate the degree of swelling (Qr) by using Eq.(1) below;

The chemical crosslinking density (nc[molcm−3]) of the samples were calculated by employing the Flory–Rehner model (Flory & Rehner, 1943) given by Eq. (2)

the v 2 is the volume fraction of the polymer in a swollen gel at equilibrium given by (1/Qr). v 1 is the molar volume of MEK. With the help of the molar v 1 of the solutions, and the solubility parameter of NBR (8.9 (cal/cm3)1/2), MEK (9.27 (cal/cm3)1/2), EPDM (8.4 (cal/cm3)1/2) and Toluene (8.94 (cal/cm3)1/2), the interaction parameters (χ1) between NBR and MEK and between EPDM and Toluene were calculated to be 0.384 and 0.45 respectively by using the Bristow et al. (1958), given by Eq. (3)

Furthermore, the total network density (n t ) deduced from the Young’s modulus test was calculated by using Eq. (4) below;

where E, nt R and T are the Young’s modulus (E)[MPa], total network density, universal gas constant (8.143 J mol−1 K−1) and temperature (K) respectively.

Tensile test and hardness (shore a)

The tensile strength measurements of the specimens were carried out according to ASTM D412 standard by using (LLOYD instrument, UK) with dumbbell shaped specimen. The specimen was subjected to stress-strain test at a cross-head speed of 500 mm/min at room temperature. The tensile properties (elongation at break (EB (%)) and tensile strength, TS (MPa)) were deduced from the stress-strain curve. The Young’s Modulus (E/MPa) of the various compounds were determined at a very low strain (<50%) using a laboratory based sample loading system. At least four samples were tested for each composition and averaged.

Dynamic mechanical analysis

The dynamic mechanical performances of neat NBR, NBR-GO/rGO and EPDM, EPDM-GO/rGO compounds were obtained using Universal TA instrument (DMA Q800 V20.24. Build 43, USA) dynamic mechanical analyzer (DMA). The average dimension of the specimen was 19 × 5 × 1 mm. The specimens were heated from −70 to70 °C at a heating rate of 10 °C/min and frequency of 11 Hz.The conditions for the frequency sweep include room temperature, 0-26 Hz frequency and 0.1% strain.

Dielectric spectroscopy

The dielectric constant of representative samples (NBR, NBR-GO/rGO and EPDM, EPDM-GO/rGO compounds) was measured by an LCR meter (VHR-200, USA). The conditions used include; 0–0.5 V, start frequency; 1 KHz, final frequency; 1000 KHz, and step frequency; 1 KHz (that was the optimum condition for the samples). Each side of the specimen was coated with conductive silver grease to improve the electrical contact between the specimens and the electrodes. The amount and number of silver coatings was maintained at the same rate and thickness to avoid variations in the thickness of the samples. All measurements were carried at room temperature. The real part (ε') of complex dielectric constant (ε∗ = ε' + iε'') and dielectric loss tangent (tan δ) were calculated using Eq. (5 & 6) as given below;

Where, ε" is the dielectric loss modulus, C is the capacitance, t is the thickness of the samples (average: ~1.3 mm), ε o is vacuum permittivity (8.85 × 10-15F/cm), and A is coated area of the samples.

Results and discussions

Morphology and state of dispersion of fillers

Previously, SEM was used to study the dispersion of GO and rGO in a NBR matrix (Mensah et al. 2014; Mensah et al. 2015). The deeply-embedded GO and rGO sheets in NBR matrix were not seen on the matrix surface initially by the SEM technique. Thus, a compressive stress was applied to the sample which made the sheets come out to the observing surfaces. A similar approach had earlier been used to study interaction of carbon nanotubes with rubber in our earlier work (Nah et al. 2010; Nah et al. 2011).

The wrinkled surface texture of the GO and rGO sheets in the composites is believed to ensure mechanical interlocking and load transfer in polymer composites (Hernández et al. 2012; Rafiee et al. 2010; Stankovich et al. 2006). It is fascinating to observe that although the same compressive strain conditions have been imposed on the EPDM-GO/rGO based systems as seen in Fig. 3(a & b), but only few GS wrinkles (shown by arrows) coated with rubber molecules can be seen at the observing surfaces of the composites; EPDM-GO-1(Fig. 3(a)) and EPDM-rGO-1 (Fig. 3(b)). Thus, it could be an indication that there is a weak interaction between EPDM and rGO/GO as the particles quickly reverted into the matrix 20 min after removal of the strain. Also, some whitish spot encircled are seen on the surface of composites, this seems to be stronger for the EPDM-rGO (Fig. 3(a)). This may be the presence of ZnO particles that bloomed onto the surface of the compounds.

Vulcanization behavior

A typical network of a matured unfilled NBR and EPDM vulcanizates is illustrated in Fig. 4(a) and (b) respectively. During vulcanization, possible sulfur links (-C-S-C-, -C-Sx-C, and -C-S-S-) are formed between the NBR polymer chains as the sulfur species attack the double (C=C) bonds of the unsaturated backbone of NBR. In this case, the unsaturated sites can be consumed resulting in infinite network formation. However, EPDM has a saturated backbone, sulfur attacks could only occur at the double bonds of the ethylidene norbornene (ENB) sites. Thus, ENB unsaturation may not be consumed but activates allylic positions and undergoes isomerism to yield sulfidic species (see Fig. 4(b)) with large number of crosslink structures (van Duin, 2002).

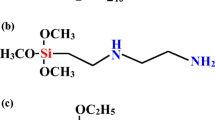

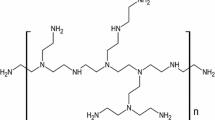

The incorporated of GO/rGO into the matrices introduce further crosslinking process (Wu et al., 2013), i.e. the oxygen moieties (-OH, or COOH) on GO/rGO could react with the curing ingredient (TMTD, ZnO, S, SA) to bond with the rubber chains (Chain-Sx-GO-Sx-Chain) as depicted in Fig. 4(c) and (d) for NBR and EPDM composites respectively. Hence, the total network density of NBR vulcanizates is likely to be higher compared to EPDM based systems, since the crosslinks are tightly packed than those of chain-ENB-Sx-ENB-chain networks with opened structures. In addition, hydrogen bonding between the GO/rGO sheets with the nitrile groups (-C ≡ N-) of NBR (see Fig. 4(b)), is possible but this may be absent in the case of EPDM systems.

Table 2 presents the cure properties; scorch time (ts2), optimum cure time (t90), minimum and maximum torque (ML,& MH) and change in torque (∆M = M H − M L )) of NBR and EPDM systems. Mixing of the GO and rGO into the rubbers generally delayed ts2 especially for the GO filled compounds. The delay in ts2 was established to be caused by absorption of the cure accelerator by the oxygen moieties on the GO/rGO sheet (Hernández et al. 2012; Mensah et al. 2014; Mensah et al. 2015; Rafiee et al. 2010; Stankovich et al. 2006). However, other factors such as; the acidic nature of the GO/rGO sheets, dispersion, wrinkling nature of the GS, thermal conductivity properties of GS, viscosity of the polymer, content of the curing ingredient (ZnO) used etc. could all contribute to delays in ts2. Meanwhile, the ts2 is closely related to the processing stability of rubber products and it is known to ensure processing safety of the final product. Also, as can be seen in Table 2, the incorporation of the GO/rGO fillers into the rubber matrix increased the cure rate index (CRI), especially for the composites compare to the gums. The rGO filled compounds showed higher CRI than GO filled systems. By comparison, the NBR-filled compounds broadly show efficient cure properties (ts2, t90, ∆M and CRI) than the EPDM based systems.

The development of the curing properties with reference to their respective rubber matrices are indicated as percentage in the brackets. The inferior cure properties of EPDM systems can be credited to its saturated and nonpolar nature.

Crosslinking density

Table 3 presents the effect of GO/rGO loading on the swelling properties (swelling degree (Qr), chemical crosslinking densities (nc) and the total network density (nt) based on the Young’s modulus, E (MPa) of the various NBR and EPDM systems. Although, different swelling solvents were used, but when comparison is made based on the reference matrices, NBR filled compounds attained lower Qr properties associated with decrease in molecular weight between crosslinks leading to decrease in free volume of the network as well as solvent permeability. The substantial development in the Qr and the corresponding nc and nt of the NBR specimen are clearly shown in the brackets as (%) with reference to the pure matrix. The increase in the densities (nc and nt) of NBR compounds may be strongly linked to the enhancement in dispersion of the rGO/GO particles into NBR matrix and their strong interactions with the polar NBR matrix (Mensah et al. 2014; Mensah et al. 2015) as illustrated earlier in Fig. 4.

Tensile and hardness properties

The tensile properties of NBR and EPDM systems have been compared in Table 4. It is evident from Table 4 that addition of the GS, increased the ultimate tensile strength (TS) as well as the Young’s modulus compared to the unfilled rubbers. When the composites are matched with their respective gums, it can broadly be seen that the NBR-filled compounds exhibit higher TS and Young’s modulus than EPDM-filled compounds (the efficiency is as expressed as % in the brackets). The high TS is associated with higher area under the stress-strain curve marked with greater strain energy density than the EPDM compounds (Mahmoud et al. 2012). This development could chiefly be caused by the strong NBR-Sx-GS-Sx-NBR restrictions provided in addition to the primary NBR-Sx-NBR networks (see Fig. 4 above). On the other hand, the poor mechanical property of the EPDM filled compounds seems to be the results of the insufficient chemical bonds between the nonpolar EPDM with the polar fillers (GO/GO). It is also interesting to observe that the GO has shown better TS in NBR than rGO, whiles rGO exhibit higher TS in EPDM than GO at higher loadings. This could indicate that the polarity of the fillers and rubbers play some role in reinforcement, since GO is more polar than rGO (Mensah et al. 2014; Mensah et al. 2015).

The success in dispersing GO and rGO in rubber matrix at lower filler concentration by using solvent mixing technique is noticeable when the tensile properties and crosslinking density measurements are compared with those of Das et al.(2012) who used melt mixing technique to dispersed expanded Graphite, graphene nanoplatelets and carbon nanotubes into nonpolar Styrene-butadiene rubber. Our compounds have achieve better reinforcement properties compared to those of Potts et al. (2013) who adopted latex and solid mixing (two-roll milling) approach to reinforce Natural rubber with 5phr exfoliated graphite oxide and carbon black (CB).

Dynamic mechanical analysis

Temperature sweep

To further examine the role of the GO and rGO in both the polar and nonpolar matrix, a DMA thermogram of representative samples of NBR and EPDM are shown in Fig. 5. (a–d). Generally, the composites showed improved storage modulus (E′[MPa]) than the unfilled elastomers. Obviously, the E′ of the GO and rGO fillers reinforce NBR matrix are higher than the EPDM compounds at all filler loadings level (see Fig. 5(a) for lower filler loadings (0.1phr of filler) and Fig. 5(b) for higher filler loading (1phr of filler)). The 0.1phr filler loading shows comparable trend in the two matrix cases, but at higher concentrations, GO particles restrain the mobility of the rubber chains with corresponding higher E′ than rGO systems (see the inserted Fig. 5(a & b)). These results agree well with the crosslinking densities (nc and nt), ∆M, the TS and E of the NBR filled compounds. Also, the energy dissipation through viscous mobility of long range polymer chains is represented by the tanδ peaks in Fig. 5(c) and (d) for NBR and EPDM systems respectively.

It was reported earlier that a smaller tanδ peak depicts higher reinforcing efficiency of the fillers (Das et al. 2011). The adequate interactions between the GO/rGO fillers with NBR and EPDM caused the tanδ peak height of the gums to depress during the dynamic deformation.

Frequency sweep

The rheological properties of the representative composites in frequency sweep mode taken from 0 to 26 Hz, 0.1% strain and at room temperature are as shown in Fig. 6. The initial in inconsistency of the stress softening observed at lower strain cycles (0-8 Hz) may be related to slippage or destabilization of the crystalline/ordered phases within the composites similar to Mullin’s effect which is basically filler-matrix breakages (Mullins, 1969) and occurs at higher deformation. Recovery from the slippage of the crystalline phases due to possible filler re-organization of Mullin’s effect proceeded as the frequency increases. From literature (Bueche, 1960; Mullins, 1969), it is possible for the stiffness of filled rubber to be recovered. The stronger interaction between GO/rGO with polar NBR matrix than EPDM is again exhibited here, even though the difference in E′ is not vigorous. It is interesting to observe that GO show higher restriction to the mobility of the rubber chains in the polar (NBR) matrix whilst rGO are compatible in the nonpolar EPDM system as frequency increases. Considering the difference in the oxygenated functionalities, GO is much polar than rGO hence such observation is practical. The relative increase in E′ as frequency increases for the NBR compounds again supports the crosslinking densities, and tensile properties presented earlier.

Reinforcement behavior evaluation

Rheological cure reinforcement factor

The reinforcement of the various rubber compounds was analyzed from the rheo-curves based on the fractional changes in the torques. The reinforcement factor αf was calculated from the equation below (Sadasivuni et al. 2014);

As clearly seen in Fig. 7, the rheological-reinforcement factor of EPDM-GO/rGO compounds shows inferior rheological-reinforcement factor behavior, compared to those of NBR-GO/rGO compounds reported earlier (Mensah et al. 2014; Mensah et al. 2015), especially at higher filler loadings.

Reinforcement by Kraus model

To confirm the graphene sheets (GS)-rubber interactions, adopted the Kraus model was adopted to quantitatively calculate the effect of particles either completely unbound, or completely and permanently bonded to the polymer (da Costa et al.2001; Kraus, 1963). The Kraus equation is given by;

where Vro, Vf are the volume fraction of the rubber in solvent-swollen gum and filled vulcanizates and ϕ is the volume fraction filler in the vulcanizates. The parameter m is the slope of Vro/Vf versus ϕ/(1- ϕ) shown in Fig. 8. The m describes how much swelling is restricted for a given volume fraction of filler and eventually the strength between filler-polymer (da Costa et al. 2001; Kraus, 1963).

The higher the value of m, the stronger the interaction between the filler and matrix. The plot of Vro/Vf versus ϕ/(1- ϕ) for the specimens are shown in Fig. 8. The theoretical prediction fits the experimental data with average regression coefficient of r2~0.96. The value of m for NBR-GO and NBR-rGO was 18.5 and 22.2 respectively, while that of EPDM-GO and EPDM-rGO compounds was 3.3 and 4.4 correspondently. Thus, the neat NBR compounds shows about 461 and 405% higher interactions with GO and rGO fillers compared to the respective interactions in EPDM filled compounds. Hence the strong interactions between GO/rGO with polar NBR are well established.

Reinforcement coefficient by DMA

The reinforcement behavior of GO and rGO in both polar (NBR) and non-polar rubber (EPDM) matrices was further evaluated by using the reinforcement coefficient (C) given in Eq. (7). Based on the difference in elastic modulus E′ between rubber and glassy state, the reinforcing effect (denoted as reinforcement coefficient C) of fillers in the polymer matrix can successfully be analyzed (Praveen et al. 2010).

where E ′g and E ′r are the storage modulus at glassy and rubber regions respectively. It is generally known that lower values of the C indicate the efficacy of the reinforcements (Praveen et al.2010). The values of E′ at glassy and rubbery states were taken at −15 and 40 °C respectively, and they are summarized in Table 5. The C values became lower as the filler loading was increased. This is therefore an evidence of the effectiveness of the fillers (rGO or GO) in reinforcing the matrix for effective stress transfer from the matrix to the nanosheets. Herein, the NBR composites demonstrate lower reinforcement coefficient (C) associated with higher mechanical behavior compared to those of EPDM compounds.

Dielectric constant property

The dielectric constants, ε´ of representative samples (NBR-GO-1, NBR-rGO-1 and EPDM-GO-1, EPDM-rGO-1) are compared in the Fig. 9. Evidently, NBR filled compounds show extremely higher ε´ values compare to those of EPDM. For example at 1000 Hz, NBR-GO-1 and NBR-rGO obtained over 370 and 453% increment in ε´ when matched with EPDM-GO-1 and EPDM-rGO-1 nanocomposites respectively.

The enhancement in the ε´ of the NBR filled compounds could be due to the high polarity nature of NBR matrix in addition to effective filler dispersion within the matrix.

Unlike NBR, EPDM is nonpolar and thus considered as poor electrical insulating material (Das et al. 2002). In all cases, the compounds filled with rGO exhibit higher ε´ than the GO filled samples. Although, interfacial polarization (IP) (the accumulation of unlocked charges at an interface) effect (Mensah et al. 2014; Tantis, et al. 2012) could play a role, however the high electrical conductivity of the rGO particles could be the major effect of the high ε´ observed for the NBR filled compounds. These conductive particles are associated with induced internal fields which neutralizes the external applied field, thus making their corresponding composites good dielectric material compared with their unfilled counterparts (Akram et al. 2005; Sutton, 1956). Nevertheless, the lower in ε´ at high frequency is a common phenomenon associated with inability of the electrical field to cope with the oscillating filed (Dang et al. 2007).

Interestingly, the increase in ε´ of the NBR systems is associated with higher loss factor (Fig. 8(b)) compared to the EPDM systems. It can be considered that the loss factor of the EPDM based systems may chiefly be due to poor electrical conduction and slow polarization currents, while that of the NBR systems may be related to other dissipative phenomena born from the strong interfacial interactions between the GS and NBR chains, as the electric field passes.

Conclusions

The reinforcement effect of GO and rGO on polar (NBR) and non-polar rubber matrix (EPDM) has been examined. The SEM texture of the samples gave a clue that GO/rGO weakly bond with nonpolar EPDM but strongly with the polar NBR matrix. Also, the NBR compounds were found to show higher cure rates than the EPDM vulcanizates. The parameters such as; TS and Young’s modulus (MPa), EB (%) and ∆M, crosslinking densities (nc and nt), Kraus parameter (m) and reinforcement coefficient (C), all confirmed that the reinforcement action of GO/rGO sheets in polar NBR matrix is superior than those of nonpolar EPDM matrix. The reinforcement action was observed to be caused mainly by improved dispersion and strong bonds (covalent and hydrogen) between NBR and GO/rGO sheets. The inferior interactions between the GO/rGO with EPDM were considered to be due to the nonpolar and saturated nature of the compound copolymer. Therefore, to reinforce rubber matrix with GSD, the polarities of the matrices and graphene selected should be considered for effective property attainment.

Abbreviations

- CB:

-

Carbon black

- CRI:

-

Cure rate index

- CZ:

-

N-cyclohexyl-2-benzothiazolesulfenamide

- DMA:

-

Dynamic Mechanical Analysis

- EB:

-

Elongation at break

- EPDM:

-

Ethylene-propylene-diene monomer

- GO:

-

Graphene oxide

- GS:

-

Graphene sheets

- GSD:

-

Graphene and/or derivative graphene sheets

- MEK:

-

Methyl ethyl Ketone

- MH :

-

Maximum torque

- ML :

-

minimum torque

- NBR:

-

Acrylonitrile Butadiene Rubber

- Phr:

-

Part per hundred rubber

- rGO:

-

Reduced graphene oxide

- S:

-

Sulfur

- SA:

-

Stearic acid

- TMTD:

-

Tetradimethylthiuram disulfide

- TS:

-

Tensile Strength

- ZnO:

-

Zinc oxide

References

Akram M, Javed A, Rizvi TZ (2005) Dielectric properties of industrial polymer composite materials. Turk J Phys 29:355–362

Allahbakhsh A, Mazinani S, Kalaee MR, Sharif F (2013) Cure kinetics and chemorheology of EPDM/graphene oxide nanocomposites. Thermochim Acta 563:22–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tca.2013.04.010

Bai X, Wan C, Zhang Y, Zhai Y (2011) Reinforcement of hydrogenated carboxylated nitrile–butadiene rubber with exfoliated graphene oxide. Carbon 49(5):1608–1613. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbon.2010.12.043

Blake P, Hill EW, Castro Neto AH, Novoselov KS, Jiang D, Yang R, Booth TJ, Geim AK (2007) Making graphene visible. Appl Phys Lett 91(6). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.2768624

Boland CS, Khan U, Backes C, O'Neill A, McCauley J, Duane S, Shanker R, Liu Y, Jurewicz I, Dalton AB, Coleman JN (2014) Sensitive, high-strain, high-rate bodily motion sensors based on graphene-rubber composites. ACS Nano 8(9):8819–8830. https://doi.org/10.1021/nn503454h

Bora C, Gogoi P, Baglari S, Dolui SK (2013) Preparation of polyester resin/graphene oxide nanocomposite with improved mechanical strength. J Appl Polym Sci 129(6):3432–3438. https://doi.org/10.1002/app.39068

Bristow GM, Watson WF (1958) Cohesive energy densities of polymers. Part 1.-cohesive energy densities of rubbers by swelling measurements. Trans Faraday Soc 54(0):1731–1741. https://doi.org/10.1039/TF9585401731

Bueche F (1960) Molecular basis for the Mullins effect. J Appl Polym Sci 4(10):107–114

Choi D, Kader MA, Cho B-H, Huh Y-i, Nah C (2005) Vulcanization kinetics of nitrile rubber/layered clay nanocomposites. J Appl Polym Sci 98(4):1688–1696. https://doi.org/10.1002/app.22341

da Costa HM, Nunes RCR, Visconte LLY, Furtado CRG (2001) Physical properties and swelling of natural rubber compounds containing rice husk ash. Kautschuk gummi. Kunststoffe 54(5):242–249

Dang ZM, Wang L, Yin Y, Zhang Q, Lei QQ (2007) Giant dielectric Permittivities in functionalized carbon-nanotube/ electroactive-polymer nanocomposites. Adv Mater 19(6):852–857. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.200600703

Das A, Kasaliwal GR, Jurk R, Boldt R, Fischer D, Stöckelhuber KW, Heinrich G (2012) Rubber composites based on graphene nanoplatelets, expanded graphite, carbon nanotubes and their combination: a comparative study. Compos Sci Technol 72(16):1961–1967. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compscitech.2012.09.005

Das A, Wang D-Y, Stoeckelhuber KW, Jurk R, Fritzsche J, Klueppel M, Heinrich G (2011) Rubber-clay nanocomposites: some recent results. In: Heinrich G (ed) Advanced rubber composites, vol 239. Advances in polymer science, pp 85–166. https://doi.org/10.1007/12_2010_96

Das N, Chaki T, Khastgir D, Chakraborty A (2002) Electrical and mechanical properties of conductive carbon black filled EVA, EPDM and their blends. Kautschuk und gummi. Kunststoffe 55(5):300–306

Flory PJ, Rehner J (1943) Statistical mechanics of cross-linked polymer networks II. Swelling. The journal of chemical physics 11(11):521–526. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1723792

Hernández M, Bernal MM, Verdejo R, Ezquerra TA, López-Manchado MA (2012) Overall performance of natural rubber/graphene nanocomposites. Compos Sci Technol 73:40–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compscitech.2012.08.012

Hong CK, Kim H, Ryu C, Nah C, Huh Y-i, Kaang S (2007) Effects of particle size and structure of carbon blacks on the abrasion of filled elastomer compounds. J Mater Sci 42(20):8391–8399. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-007-1795-3

Kang H, Zuo K, Wang Z, Zhang L, Liu L, Guo B (2014) Using a green method to develop graphene oxide/elastomers nanocomposites with combination of high barrier and mechanical performance. Compos Sci Technol 92:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compscitech.2013.12.004

Kraus G (1963) Swelling of filler-reinforced vulcanizates. J Appl Polym Sci 7(3):861–871. https://doi.org/10.1002/app.1963.070070306

Li F, Yan N, Zhan Y, Fei G, Xia H (2013) Probing the reinforcing mechanism of graphene and graphene oxide in natural rubber. J Appl Polym Sci 129(4):2342–2351. https://doi.org/10.1002/app.38958

Li Y, Wang Q, Wang T, Pan G (2011) Preparation and tribological properties of graphene oxide/nitrile rubber nanocomposites. J Mater Sci 47(2):730–738. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-011-5846-4

Li Y, Wang Q, Wang T, Pan G (2012) Preparation and tribological properties of graphene oxide/nitrile rubber nanocomposites. J Mater Sci 47(2):730–738. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-011-5846-4

Mahmoud WE, Al-Ghamdi AA, Al-Solamy FR (2012) Evaluation and modeling of the mechanical properties of graphite nanoplatelets based rubber nanocomposites for pressure sensing applications. Polym Adv Technol 23(2):161–165. https://doi.org/10.1002/pat.1840

Mensah B, Kim S, Arepalli S, Nah C (2014) A study of graphene oxide-reinforced rubber nanocomposite. J Appl Polym Sci 131(16). https://doi.org/10.1002/app.40640

Mensah B, Kumar D, Lim D-K, Kim SG, Jeong B-H, Nah C (2015) Preparation and properties of acrylonitrile–butadiene rubber–graphene nanocomposites. Journal of applied polymer science 132 (36):n/a-n/a. https://doi.org/10.1002/app.42457

Mullins L (1969) Softening of rubber by deformation. Rubber Chem Technol 42(1):339–362

Nah C, Lim JY, Cho BH, Hong CK, Gent AN (2010) Reinforcing rubber with carbon nanotubes. Journal of Applied Polymer Science:n/a-n/a. https://doi.org/10.1002/app.32524

Nah C, Lim JY, Sengupta R, Cho BH, Gent AN (2011) Slipping of carbon nanotubes in a rubber matrix. Polym Int 60(1):42–44. https://doi.org/10.1002/pi.2909

Novoselov KS, Geim AK, Morozov SV, Jiang D, Zhang Y, Dubonos SV, Grigorieva IV, Firsov AA (2004) Electric field effect in atomically thin carbon films. Science 306(5696):666–669. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1102896

Potts JR, Shankar O, Murali S, Du L, Ruoff RS (2013) Latex and two-roll mill processing of thermally-exfoliated graphite oxide/natural rubber nanocomposites. Compos Sci Technol 74:166–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compscitech.2012.11.008

Praveen S, Chattopadhyay PK, Jayendran S, Chakraborty BC, Chattopadhyay S (2010) Effect of nanoclay on the mechanical and damping properties of aramid short fibre-filled styrene butadiene rubber composites. Polym Int 59(2):187–197. https://doi.org/10.1002/pi.2706

Qiu J, Wang S (2011) Enhancing polymer performance through graphene sheets. J Appl Polym Sci 119(6):3670–3674. https://doi.org/10.1002/app.33068

Rafiee MA, Rafiee J, Srivastava I, Wang Z, Song H, Z-Z Y, Koratkar N (2010) Fracture and fatigue in graphene nanocomposites. Small 6(2):179–183. https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.200901480

Sadasivuni KK, Ponnamma D, Thomas S, Grohens Y (2014) Evolution from graphite to graphene elastomer composites. Prog Polym Sci 39(4):749–780. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2013.08.003

Stankovich S, Dikin DA, Dommett GHB, Kohlhaas KM, Zimney EJ, Stach EA, Piner RD, Nguyen ST, Ruoff RS (2006) Graphene-based composite materials. Nature 442(7100):282–286. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature04969

Sutton LE (1956) Dielectric behavior and structure. Dielectric constant and loss, dipole moment and molecular structure. J Am Chem Soc 78(2):507–508. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja01583a080

Tan J, Chao YJ, Yang M, Williams CT, Van Zee JW (2008) Degradation characteristics of elastomeric gasket materials in a simulated PEM fuel cell environment. J Mater Eng Perform 17(6):785–792. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11665-008-9233-5

Tantis I, Psarras GC, Tasis D (2012) Functionalized graphene - poly(vinyl alcohol) nanocomposites: physical and dielectric properties. Express Polym Lett 6(4):283–292. https://doi.org/10.3144/expresspolymlett.2012.31

Tseng IH, Liao Y-F, Chiang J-C, Tsai M-H (2012) Transparent polyimide/graphene oxide nanocomposite with improved moisture barrier property. Mater Chem Phys 136(1):247–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matchemphys.2012.06.061

Valentini L, Bolognini A, Alvino A, Bon SB, Martin-Gallego M, Lopez-Manchado MA (2014) Pyroshock testing on graphene based EPDM nanocomposites. Composites Part B-Engineering 60:479–484. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesb.2013.12.022

Van Duin M (2002) Chemistry of EPDM cross-linking. Kautschuk gummi. Kunststoffe 55(4):150–154

Varghese TV, Ajith Kumar H, Anitha S, Ratheesh S, Rajeev RS, Lakshmana Rao V (2013) Reinforcement of acrylonitrile butadiene rubber using pristine few layer graphene and its hybrid fillers. Carbon 61:476–486. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbon.2013.04.104

Wei J, Jacob S, Qiu J (2014) Graphene oxide-integrated high-temperature durable fluoroelastomer for petroleum oil sealing. Compos Sci Technol 92:126–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compscitech.2013.12.010

Wu J, Xing W, Huang G, Li H, Tang M, Wu S, Liu Y (2013) Vulcanization kinetics of graphene/natural rubber nanocomposites. Polymer 54(13):3314–3323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polymer.2013.04.044

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Author’s contribution

BM carried out preparation of graphene materials (GO and rGO) and analysis of chemical and mechanical properties studied in this paper, SK participated the sample preparation and physical measurements of rubber compounds by melt blending. WW participated the literature survey and revising of the manuscript, and CN conceived of the study, and participated in its design and coordination and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by both the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (NRF-2016R1D1A3B03932709) and The Leading Human Resource Training Program of Regional Neo industry through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT and future Planning (NRF-2016H1D5A1910159).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Mensah, B., Kang, S.I., Wang, W. et al. Effect of graphene on polar and nonpolar rubber matrices. Mech Adv Mater Mod Process 4, 1 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40759-017-0034-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40759-017-0034-0