Abstract

This paper examines a cluster of phenomena in Mandarin Chinese, which may collectively be characterized as “affective constructions”. Based on the diversified and sometimes hybrid nature of these affective construals, we argue that the usual dichotomy between high and low applicatives is not enough to capture their syntactic and semantic idiosyncrasies. We will need a more elaborate theory to map out the topography of applicatives under the cartographic approach. It is shown that Chinese affectives have an unusual distribution extending far beyond the boundary of the vP phase, which in turn argues for an independent applicative projection in the left periphery, presumably associated with speaker-orientedness and a presupposition of unexpectedness.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

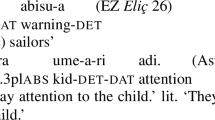

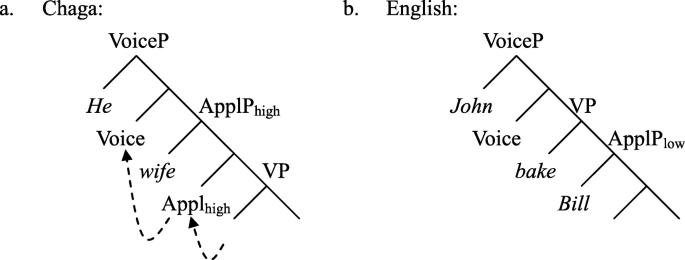

In the literature, applicatives are often characterized as syntactic projections hosting extra arguments within the vP phase (cf. Georgala et al. 2008; Harley 2002; Hole 2006; Marantz 1984, 1993; McGinnis 2001; Pesetsky 1995; Pylkkänen 2002). In particular, Pylkkänen proposes to separate applicative constructions into two types, namely, the high applicative as in the Chaga example (1) vs. the low applicative in the English example (2):

-

(1)

N-˝a-˝ı-lyì-í-à__'m-kà__k-élyá. (Bresnan and Moshi 1990)

FOC-1sg-PR-eat-APPL-FV__1-wife__7-food

He is eating food for (his) wife.

-

(2)

John baked Bill a cake.

In terms of semantics, high applicatives typically differ from low applicatives in not involving a directional possessive relationship. As illustrated in the diagram (3a), the high applicative head takes a DP specifier and a VP complement, relating a Beneficiary argument to an event denoted by the main verb. By contrast, the low applicative head in (3b) takes a DP specifier and a DP complement, expressing a directional possessive relationship between two individuals, i.e., the Recipient Bill and the Theme a cake:

-

(3)

In this light, we may consider the following pair of affective construals in Mandarin Chinese:

-

(4)

-

a.

他居然[給我]喝了三瓶酒!

tā__jǖrán__[gěi__wǒ]__hē-le__sān-píng__jǐu

he__unexpectedly__[AFF__me]__drink-Prf__three-bottle__wine

Unexpectedly, he drank three bottles of wine on me!

-

b.

他居然喝了我三瓶酒。

tā__jǖrán__hē-le__wǒ__sān-píng__jiǔ

he__unexpectedly__drink-Prf__me__three-bottle__wine

Unexpectedly, he drank three bottles of wine on me!

-

a.

On the surface, both sentences involve an affective relation between the Affectee 我 wǒ ‘me’ and the wine-drinking event. Upon a closer look, it becomes clear that (4a) differs from (4b) in a number of ways:

-

I.

In terms of syntax, the affective construal of (4a) is signaled by an applicative marker 給 gěi, which has its verbal origin as ‘give’. (4b), on the other hand, assumes a configuration often dubbed “pseudo double object construction”, in that there is no directional possession between the Affectee and the Theme argument.

-

II.

There is a truth-conditional distinction between the two sentences: In the scenario that a doctor asked a patient not to drink wine at home, but the patient did not follow the instruction, the doctor may utter (4a), but not (4b). In fact, the latter construal seems to require the Affectee to the source of the three bottles of wine, in direct contrast with the “to-the-possession-of” reading of English low applicatives such as (2).

-

III.

Finally, there is a person restriction on the Affectee of (4a): The ungrammaticality of (5a)–(5c) indicates that it can only be a first-person singular pronoun, hence speaker-oriented. By contrast, the same restriction is not observed for (4b), as evidenced by the well-formedness of (6a)–(6c):

-

(5)

-

a.

* 他居然[給我們]喝了三瓶酒!

tā__jǖrán__[gěi__wǒmen]__hē-le__sān-píng__jǐu

he__unexpectedly__[AFF__us]__drink-Prf__three-bottle__wine

-

b.

* 他居然[給你/你們]喝了三瓶酒!

tā__juran__[gei__ni/nimen]__he-le__san-ping__jiu

he__unexpectedly__[AFF__you/you(pl.)]__drink-Prf__three-bottle__wine

-

c.

* 他居然[給他/他們]喝了三瓶酒!

ta__jǖrán__[gěi__tā/tāmen]__hē-le__sān-píng__jǐu

he__unexpectedly__[AFF__him/them]__drink-Prf__three-bottle__wine

-

a.

-

(6)

-

a.

他居然喝了我們三瓶酒!

tā__jǖrán__hē-le__wǒmen__sān-píng__jǐu

he__unexpectedly__drink-Prf__us__three-bottle__wine

Unexpectedly, he drank three bottles of wine on us!

-

b.

他居然喝了你/你們三瓶酒!

tā__jǖrán__hē-le__nǐ/nǐmen__sān-píng__jǐu

he__unexpectedly__drink-Prf__you/you(pl.)__three-bottle__wine

Unexpectedly, he drank three bottles of wine on you!

-

c.

他居然喝了他/他們三瓶酒!

tā__jǖrán__hē-le__tā/tāmen__sān-píng__jǐu

he__unexpectedly__drink-Prf__him/the__three-bottle__wine

Unexpectedly, he drank three bottles of wine on him/them!

-

a.

In the following discussion, we may call (4a) an outer affective and (4b) an inner affective.Footnote 1 I will show that the properties of Mandarin affectives presented above can be accommodated if a novel notion “middle applicative” is introduced at the vP phase, which in turn provides a coherent account of a variety of affective and benefactive construals in Mandarin Chinese. In Section 2, we employ a few more criteria to check upon the peripheral status of the outer applicative in (4a) and to see if there is indeed a gray area in-between highest and lowest applicatives. Along the same line, Section 3 examines the inner applicative in the pseudo double object construction (4b).

2 Applicatives in the left periphery

2.1 Applicativity tests

In addition to the possession test mentioned above, there are two additional criteria in the literature for determining the height of an applicative projection; that is, the transitivity test and the passivization test (cf. McGinnis 2001; Pylkkänen 2002): The first test has to do with the fact that low applicatives cannot combine with an unergative predicate, as shown by the contrast between (7b) and (8b):

-

(7)

-

a.

John baked a cake. [transitive]

-

b.

John baked Bill a cake.

-

a.

-

(8)

-

a.

I ran. [unergative]

-

b.

*I ran him.

-

a.

So one can derive a low applicative such as (7b) from a transitive sentence like (7a), whereas it is impossible for an unergative such as (8a) to derive (8b). On the other hand, high applicatives are quite compatible with an unergative predicate, as evidenced by the Chaga example (9):

-

(9)

N-˝a-˝ı-lyì-í-à__'m-kà. [unergative] (Bresnan and Moshi 1990)

FOC-1s-PR-eat-APPL-FV__1-wife

He is eating for/on (his) wife.

The second test concerns the observation that low applicatives only allow passivization of an indirect object (IO), as shown by the contrast between (10a) and (10b):

-

(10)

-

a.

Bill was baked a cake by John. [ApplPlow, IO passivized]

-

b.

* A cake was baked Bill by John. [ApplPlow, *DO passivized]

-

a.

High applicatives, on the other hand, do not have such restriction. As pointed out by McGinnis (2001, 2003), both high and low applicatives appear in Kinyarwanda, where benefactive constructions allow both IO and DO to undergo passivization, as illustrated in (11a) and (11b) respectively:

-

(11)

-

a.

umukoôbwak__a-ra-andik-ir-w-a__tk__íbárúwa__n’ûmuhuûngu.

girlk__SP-Pres-write-Appl-Pass-Asp__tk__letter__by.boy

The girl is having the letter written for her by the boy. [ApplPhigh, IO passivized]

-

b.

íbárúwak__i-ra-andik-ir-w-a__umukoôbwa__tk__n’ûmuhuûngu.

letterk__SP-Pres-write-Appl-Pass-Asp__girl__tk__by.boy

The letter is written for the girl by the boy. [ApplPhigh, DO passivized]

-

a.

So both (11a) and (11b) should be classified as high applicatives. On the other hand, the contrast between (12a) and (12b) shows that only IO but not DO can be passivized in Kinyarwanda locative constructions:

-

(12)

-

a.

ishuûrik__ry-oohere-j-w-é-ho__tk__igitabo__n’úúmwáalímu.

schoolk__SP-send-Asp-Pass-Asp-Loc__tk__book__by.teacher

The school was sent the book by the teacher. [ApplPlow, IO passivized]

-

b.

* igitabok__cy-oohere-j-w-é-ho__ishuûri__tk__n’úúmwáalímu.

bookk__SP-send-Asp-Pass-Asp-Loc__school__tk__by.teacher

The book was sent to school by the teacher. [ApplPlow, *DO passivized]

-

a.

These locative construals therefore count as instances of low applicatives. As a result, we have secured some reliable tests at hand to map out the topography of applicatives across languages.

Now, we are in a position to apply the tests one by one to outer affectives in Mandarin: First, consider (4a). As revealed by its truth-conditional distinction from (4b), there is no directional possessive relationship between the Affectee wǒ ‘me’ and the Theme 三瓶酒 sān-píng jǐu ‘three bottles of wine’. So it fails the possession test. Secondly, this type of affectives has no trouble with taking an unergative predicate, as in (13), passing the transitivity test with flying colors:

-

(13)

他居然[給我]哭了。

tā__jǖrán__[gěi__wǒ]__kū-le

he__unexpectedly__[AFF__me]__cry-Inc

Unexpectedly, he started crying on me.

Both results indicate that (4a) belongs to the class of high applicatives. The passivization test, on the other hand, is rather inconclusive: Passivization appears to be blocked for both IO and DO, as in (14a) and (14b) respectively:

-

(14)

-

a.

* 我被他居然給喝了三瓶酒。

wǒ__bèi__tā__jǖrán__gěi__hē-le__sān-píng__jǐu

I__BEI__he__unexpectedly__AFF__drink-Prf__three-bottle__wine

-

b.

* 有三瓶酒被他居然[給我]喝了。

yǒu__sān-píng__jǐu__bèi__tā__jǖrán__[gěi__wǒ]__hē-le

have__three-bottle__wine__BEI__he__unexpectedly__[AFF__me]__drink-Prf

-

a.

2.2 Peripheral construals of Mandarin outer affectives

The next step is to see how Mandarin affectives should be encoded in syntactic structures. In the following discussion, I will attempt to show that the so-called high applicatives are not high enough, and there are even higher applicatives merged to the left periphery (or to the CP phase to the same effect). They display a cluster of properties typically associated with the information structure.

Our first argument is built upon the fact that the outer affective of (15a) ((4a) repeated here) is licensed through a special kind of illocutionary force. As indicated by the following contrast, the presence of the evaluative adverb 居然 jūrán ‘unexpectedly’ is obligatory, without which the sentence becomes declarative, and is ruled out consequently, as in (15b):

-

(15)

-

a.

他居然[給我]喝了三瓶酒!

tā__jǖrán__[gěi__wǒ]__hē-le__sān-píng__jǐu

he__unexpectedly__[AFF__me]__drink-Prf__three-bottle__wine

Unexpectedly, he drank three bottles of wine on me!

-

b.

* 他[給我]喝了三瓶酒。

tā __[gěi__wǒ]__hē-le__sān-píng__jǐu

he__[AFF__me]__drink-Prf__three-bottle__wine

-

a.

The same restriction does not apply to its inner counterpart in (16a) ((4b) repeated here). As indicated by the well-formedness of (16b), the pseudo double object construal does not require an evaluative adverb and is quite compatible with the declarative usage:

-

(16)

-

a.

他居然喝了我三瓶酒!

tā__jǖrán__hē-le__wǒ__sān-píng__jǐu

he__unexpectedly__drink-Prf__me__three-bottle__wine

Unexpectedly, he drank three bottles of wine on me!

-

b.

他喝了我三瓶酒。

tā__hē-le__wǒ__sān-píng__jǐu

he__drink-Prf__me__three-bottle__wine

He drank three bottles of wine on me.

-

a.

Interestingly enough, the licenser in question can also be replaced either by a reversal adverb like 卻 qùe ‘however’ in (17a) or by an outer wh-adverb such as 怎麼 zěnme ‘how come’ in (17b):

-

(17)

-

a.

我叫他幫我買酒。他卻給我買了菸!

wǒ__jìao__tā__bāng__wǒ__mǎi__jǐu__tā__qǜe__[gěi__wǒ]__mǎi-le__yān

I__ask__him__help__me__buy__wine__he__however__[AFF__me]__buy-Prf__cigarette

I asked him to help me to buy wine. He, however, bought cigarettes on me!

-

b.

我叫他幫我買酒。他怎麼[給我]買了菸?!

wǒ__jìao__tā__bāng__wǒ__mǎi__jǐu__tā__zěnme__[gěi__wǒ]__mǎi-le__yān

I__ask__him__help__me__buy__wine__he__how.come__[AFF__me]__buy-Prf__cigarette

I asked him to help me to buy wine. How come he bought cigarettes on me?!

-

a.

In addition, this type of affective construals can also be licensed by imperative and negative moods, as illustrated by (18a) and (18b) respectively:

-

(18)

-

a.

[給我]跪下!

[gěi__wǒ]__gùi-xìa

[AFF__me]__kneel-down

Kneel down for my sake!

-

b.

阿Q從沒[給我]丟過臉!

ākīu__cóng-méi__[gěi__wǒ]__dīu-gùo__lǐan

Akiu__ever-have.not__[AFF__me]__lose-Exp__face

Akiu has never lost face on me!

-

a.

Another argument stems from the fact that outer affectives marked by gěi is strictly speaker-oriented: As mentioned above, the Affectee argument in question can only be first-person singular, as in (5a)–(5c), and there is again no such restriction for their inner counterparts throughout (6a)–(6c). Furthermore, there is a presupposition associated with the affective construal of (15a), i.e., the wine-drinking event should never happen in the first place. As noted by Shu (2008), certain sentential adverbials carry a focus interpretation, and an evaluative adverb like jǖrán ‘unexpectedly’ may well take a focused constituent as its complement. Therefore, it seems reasonable to suggest that the focused portion of (15a) (presumably IP) carries the new information “he drank three bottles of wine”, which is indeed unexpected given the presupposition mentioned above. All these are the hallmark of peripheral construals associated with the information structure and should therefore be encoded syntactically on the complementizer layer.

From a cross-linguistic point of view, there is a class of non-argumental clitics in Modern Greek (and Romance languages in general) which are very much in line with the peripheral construals of Mandarin affectives. They typically express some sort of affectedness between an individual and an event. These so-called ethical datives observe a speaker/hearer-oriented restriction similar to Mandarin high affectives (cf. Cuervo 2003; Jaeggli 1982; Michelioudakis and Sitaridou 2008; Perlmutter 1971, among others), as in (19):

-

(19)

mu/su/?tu arostise i Maria.

me/you/him__fell.ill__on__Mary

Mary fell ill on me/you/him.

Modern Greek ethical datives also require licensing from imperative, optative, subjunctive, or negative moods, as shown by the contrast between (20a) and (20b):

-

(20)

-

a.

na mu prosechis! [imperative]

Subj__eth.dat.1S__take.care

Take care, for my sake!

-

b.

?? mu prosechis. [??declarative]

eth.dat.1S__take.care

You take care, for my sake.

-

a.

These clitics are often analyzed either as CP adjuncts (cf. Catsimali 1989) or as the realization of the φ-features of a high applicative head which takes the whole event as its argument, merging well beyond vP (cf. Cuervo 2003).

Our observations thus point to the conclusion that the otherwise puzzling restrictions on outer affective construals have a close bearing on the force and/or mood of the entire sentence. In other words, the “extra” argument introduced by gei may well be associated with some functional projection beyond the vP phase, presumably taking its hold in the left periphery.

2.3 Mapping the topography of Mandarin high applicatives

One question still remains as to how to separate Mandarin outer affectives from their benefactive/goal counterparts, which are also marked by gěi, as exemplified by (21a) and (21b):

-

(21)

-

a.

阿Q[給我/我們/你/你們/他/他們]烤了一塊蛋糕。 [benefactive]

ākīu__[gěi__wǒ/wǒmen/nǐ/nǐmen/tā/tāmen]__kǎo-le__yí-kùai__dàngāo

Akiu__[for__me/us/you/you(pl.)/him/them]__bake-Prf__one-CL__cake

Akiu baked a cake for me/us/you/you(pl.)/him/them.

-

b.

阿Q[給我/我們/你/你們/他/他們]寫了一封信。 [goal]

ākīu__[gěi__wǒ/wǒmen/nǐ/nǐmen/tā/tāmen]__xǐe-le__yì-fēng__xìn

Akiu__[to__me/us/you/you(pl.)/him/them]__write-Prf__one-CL__letter

Akiu wrote a letter to me/us/you/you(pl.)/him/them.

-

a.

For one thing, it is impossible to topicalize the outer Affectee along with gěi to the sentence-initial position, as evidenced by the contrast between (22a) and (22b). By contrast, there is no such restriction for benefactive and goal construals, which can be made clear by comparing (21a) and (21b) with (23a) and (23b) respectively:

-

(22)

-

a.

阿Q居然[給我]拿了錢就跑。

ākīu__jǖrán__[gěi__wǒ]__ná-le__qían__jìu__pǎo

Akiu__unexpectedly__[AFF__me]__take-Prf__money__then__run

Unexpectedly, Akiu took the money and ran away on me.

-

b.

* [給我], 阿Q居然拿了錢就跑。

[gěi__wǒ]__ākīu__ jǖrán__ná-le__qían__jìu__pǎo

[AFF__me]__Akiu__unexpectedly__take-Prf__money__then__run

Unexpectedly, Akiu took the money and ran away on me.

-

a.

-

(23)

-

a.

? [給他們], 阿Q烤了一塊蛋糕。

[gěi__tāmen]__ākīu__kǎo-le__yí-kùai__dàngāo

[for__them]__Akiu__bake-Prf__one-CL__cake

Akiu baked a cake for them.

-

b.

[給他們], 阿Q寫了一封信。

[gěi__tāmen]__ākīu__xǐe-le__yì-fēng__xìn

to__them__Akiu__write-Prf__one-CL__letter

Akiu wrote a letter to them.

-

a.

This indicates that gěi may well serve as a true applicative head in outer affective construals, while it is merely a preposition forming a constituent with the Beneficiary/Goal argument.

For another thing, it is possible to distinguish the outer Affectee in question from a Beneficiary argument by their word ordering relative to a manner adverb such as 慢慢地 mànmàndi ‘slowly’. As illustrated in (24a), the reading is affective when the gěi phrase precedes the manner adverb, and we may change it into benefactive by placing the gěi phrase after the manner adverb, as in (24b):

-

(24)

-

a.

阿Q居然[給我]慢慢地擦地板。 [affective]

ākīu__jǖrán__[gěi__wǒ]__mànmàndi__cā__dìbǎn

Akiu__unexpectedly__[AFF__me]__slowly__wipe__floor

Unexpectedly, Akiu slowly wiped the floor on me.

-

b.

阿Q居然慢慢地[給人家]擦地板。 [benefactive]

ākīu__jǖrán__mànmàndi__[gěi__rénjīa]__cā__dìbǎn

Akiu__unexpectedly__slowly__[for__people]__wipe__floor

Unexpectedly, Akiu slowly wiped the floor for others.

-

a.

In fact, the two construals can marginally co-occur in the same sentence, separated by the manner adverb, as evidenced by (25):

-

(25)

? 阿Q居然[給我]慢慢地[給人家]擦地板。

ākīu__jǖrán__[gěi__wǒ]__ mànmàndi __[gěi__rénjīa]__cā__dìbǎn

Akiu__unexpectedly__[AFF__me]__slowly__[for__people]__wipe__floor

Unexpectedly, Akiu slowly wiped the floor for others on me.

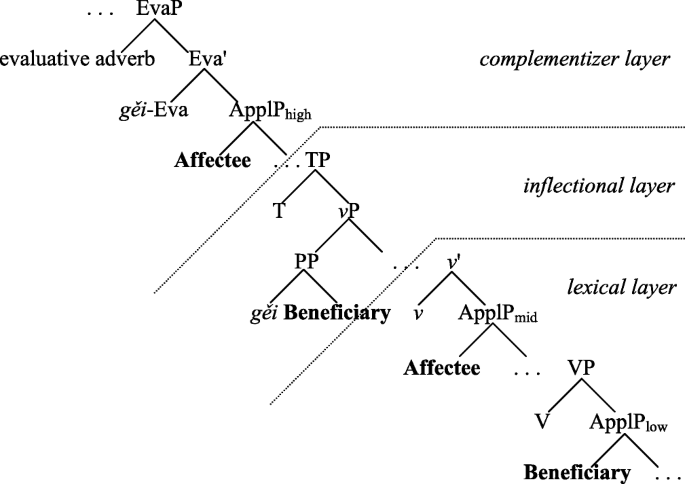

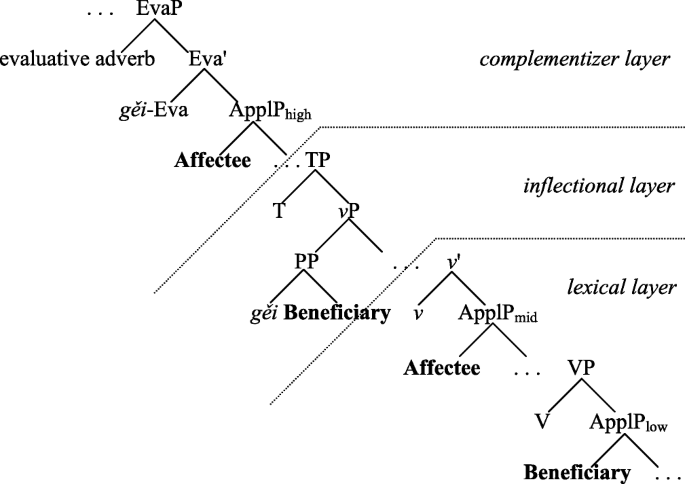

The intuition explored above can then be implemented under the split CP approach pioneered by Rizzi (1997), as visualized in the following diagram (irrelevant details omitted):

-

(26)

The topography of Mandarin outer affectives and benefactives

Here, we envision the affective gěi to be a high applicative head, which hosts the outer Affectee. It raises to the evaluative head subsequently to license the peripheral construals of outer affectives. As for the benefactive (and goal) PP, we place it at the peripheral area of vP as a working hypothesis (also cf. Cinque 1999), separated from the inflectional layer only by the manner adverb, presumably a delimitator for the vP phase.

For one thing, it may seem a bit overstretched to place an applicative projection as high as the complementizer layer. Nevertheless, given the definition that a high applicative dependency holds between an individual and an event, we should expect a natural extension to the left periphery if the applied argument is involved in a speaker/addressee-oriented construal. In fact, it has been suggested by Buell (2003) that DP locative applicatives in Zulu must merge above the Agent (hence outside vP). A similar proposal is also made by McGinnis and Gerdts (2003) for Kinyarwanda benefactives, based on the locality effects observed in various types of multiple applicatives. It is thus not unimaginable that, through the process of grammaticalization along the line of Roberts and Roussou (1999), an applicative can evolve a step further into the domain of peripheral construals.

Our treatment also accounts for the fact that the passivization test turns out to be inconclusive in Mandarin. This is because the affectivity involved is far beyond the core argument structure associated with vP, and therefore does not observe the usual morpho-syntax of passives.

3 Applicatives at the edge of vP

3.1 Inner affectives vs. inner benefactives

The next logical question to ask is how the inner affectives in Mandarin fair with their outer counterparts in terms of applicativity. As mentioned above, here, we have another breed of affectives which are not marked by gěi (cf. Zhang 1998, among many others), forming the now familiar pseudo double object constructions (pseudo-DOCs). Like high applicatives, inner affectives involve a relation between an individual and an event, as in (27):

-

(27)

阿Q喝了小D三瓶酒。

ākīu__hē-le__xǐaodī__sān-píng__jǐu

Akiu__drink-Prf__Xiaodi__three-CL__wine

Akiu drank three bottles of wine on Xiaodi.

Unlike high applicatives, the Affectee (IO) can undergo passivization, as in (28a), whereas the same construal is not available for the Theme (DO), as evidenced by (28b). Moreover, the inner affective construal is incompatible with unergatives, as illustrated by the contrast between (29a) and (29b). So they fail both the passivization and transitivity tests and should not be analyzed as high applicatives:

-

(28)

-

a.

小D被阿Q喝了三瓶酒。 [IO passivized]

xǐaodī__bèi__ākīu__hē-le__sān-píng__jǐu

Xiaodi __BEI__Akiu__drink-Prf__three-CL__wine

Xiaodi underwent the event Akiu drank three bottles of wine on him.

-

b.

* 有三瓶酒被阿Q喝了小D。 [*DO passivized]

yǒu__sān-píng__jǐu__bèi__ākīu__hē-le__xǐaodī

have__three-CL__wine__BEI__Akiu__drink-Prf__Xiaodi

-

a.

-

(29)

-

a.

阿Q喝醉了。

ākīu__hē-zùi__le

Akiu__drink-drunk__Inc

Akiu got drunk.

-

b.

* 阿Q喝醉小D了。

ākīu__hē-zùi__xǐaodī__le

Akiu__drink-drunk__Xiaodi__Inc

-

a.

In terms of pragmatics, inner affectives do not observe the speaker-oriented restriction, as we have already seen above. Moreover, the evaluative adverb jǖrán ‘unexpectedly’ can certainly be omitted in a pseudo-DOC construal such as (27). So there is no reason to place them in the left periphery. In terms of semantics, the Affectee does maintain some form of possessive relation to the Theme argument, which presents a sharp contrast to their counterparts in outer affectives. On the other hand, it is not the kind of directional possession typically found in DOCs either (cf. Harley 2002; McGinnis 2001; Pylkkänen 2002). We may characterize it either as a “from-the-possession-of” relationship in Pylkkänen’s terms or as a possessive relation implied by the affectedness of the wine-drinking event.

At this stage, it may seem reasonable to identify Mandarin inner affectives with low applicatives while analyzing the IO as a Source rather than an Affectee. However, there are also reasons to believe otherwise. As pointed out by Huang (2007), not all the Affectee in pseudo-DOCs can be said to take part in the “from-the-possession-of” relationship: As shown below, the IO is in no sense a Source for the DO 玩笑 wánxìao ‘joke’:

-

(30)

老天開了小D一個大玩笑。

lǎotīan__kāi-le__xǐaodī__yí-ge__dà__wánxìao

heaven__play-Prf__Xiaodi__one-CL__big__joke

Heaven played a big joke on Xiaodi.

It is also instructive to note that the semantics of inner affectives is very much in line with Spanish affected datives such as (31a), where the possessive relation between the Affectee and the Theme can be canceled (cf. Cuervo 2003), as in (31b):

-

(31)

-

a.

Emilio le rompió la radio a Carolina.

Emilio__Cl.Dat__broke__the__radio__Carolina.Dat

Emilio broke the radio on Carolina.

-

b.

Emilio le rompió [la radio de la vecina] a Carolina.

Emilio__Cl.Dat__broke__[the__radio__of__the__neighbor]__Carolina.Dat

Emilio broke the neighbor’s radio on Carolina.

-

a.

In other words, we can add a possessor distinct from the Affectee to the Theme of (27), and the sentence is still grammatical, as exemplified below:

-

(32)

阿Q喝了小D[三瓶趙家的酒]。

ākīu__hē-le__xǐaodī__[sān-píng__zhào-jīa__de__jǐu]

Akiu__drink-Prf__Xiaodi__[three-CL__Zhao-family__Poss__wine]

Akiu drank three bottles of Zhao family’s wine on Xiaodi.

This means that the possession between the two internal arguments of the pseudo double object construction is only implied and can therefore be canceled. It follows that the possessive relation in question is not part of the structural semantics of Mandarin inner affectives, where the IO should be analyzed as an Affectee rather than a Source.

Furthermore, there is another class of benefactives which arguably situates even lower in the syntactic hierarchy, bearing some resemblance to English low applicatives: There is a possessive relation between the Beneficiary (IO) and the Theme (DO), but it is by no means directional, as in (33a):

-

(33)

阿Q修了趙家三扇門。

ākīu__xīu-le__zhào-jīa__sān-shàn__mén

Akiu__fix-Prf__Zhao-family__three-CL__door

Akiu fixed three doors for the Zhao family.

With respect to the transitivity test, this Mandarin “inner” benefactive is incompatible with unergative predicates like 哭 kū ‘cry’, siding with English low applicatives, as illustrated belowFootnote 2:

-

(34)

* 阿Q哭了趙家。

ākīu__kū-le__zhào-jīa

Akiu__cry-Prf__Zhao-family

On the other hand, neither IO nor DO may undergo passivization, as evidenced by the ungrammaticality of (35a) and (35b):

-

(35)

-

a.

* 趙家被阿Q修了三扇門。 [*IO passivized]

zhào-jīa__bèi__ākīu__xīu-le__sān-shàn__mén

Zhao-family__BEI__Akiu__fix-Prf__three-CL__door

-

b.

* 三扇門被阿Q修了趙家。 [*DO passivized]

sān-shàn__mén__bèi__ākīu__xīu-le__zhào-jīa

three-CL__door__BEI__Akiu__fix-Prf__Zhao-family

-

a.

Interestingly enough, it seems that inner benefactives also have a counterpart in Spanish, i.e., a special kind of low applicatives where the possessive relation between IO and DO is static rather than directional, as in (36a):

-

(36)

-

a.

Emilio le lavó el auto a Carolina.

Emilio__Cl.Dat__washed__the__car__Carolina.Dat

Lit. Emilio washed Carolina the car.

-

b.

* Emilio le lavó [el auto de la vecina] a Carolina.

Emilio__Cl.Dat__washed__[the__car__of__the__neighbor]__Carolina.Dat

Lit. Emilio washed Carolina the car of the neighbor.

-

a.

As Cuervo (2003) points out, here, the possession cannot be canceled, as in (36b), and should belong to the structural semantics of the dative construction. Likewise, Mandarin inner affectives show the same trait: The possessive relation between the Beneficiary and the Theme of (33) is entailed, and hence uncancelable, as shown by the deviance of (37):

-

(37)

* 阿Q修了趙家[三扇小D的門]。

ākīu__xīu-le__zhào-jīa__[sān-shàn__xǐaodī__de__mén]

Akiu__fix-Prf__Zhao-family__[three-CL__Xiaodi__Poss__door]

So the question boils down to how inner affectives should be distinguished from inner benefactives in a principled manner. One way to think of this issue is to suggest that they both involve an applicative projection of some sort, but differ in their structural height, namely, inner affectives merge above VP, while their benefactive counterparts embed within VP.

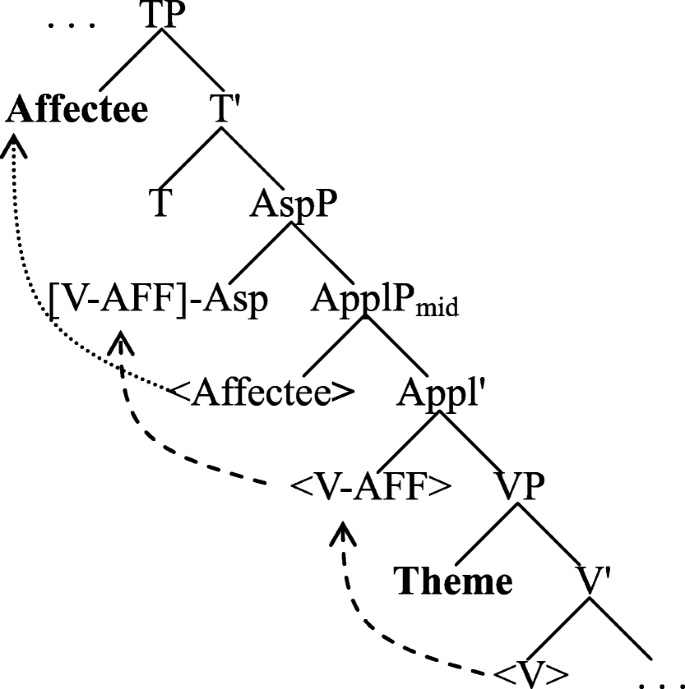

3.2 A phase-theoretic account of applicatives

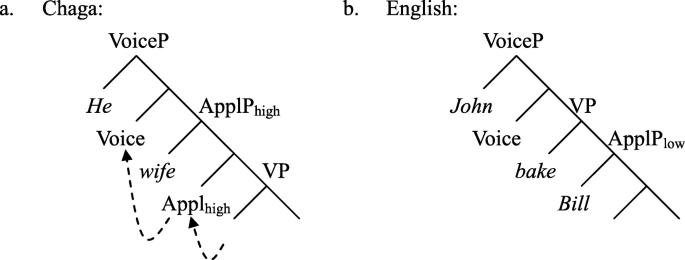

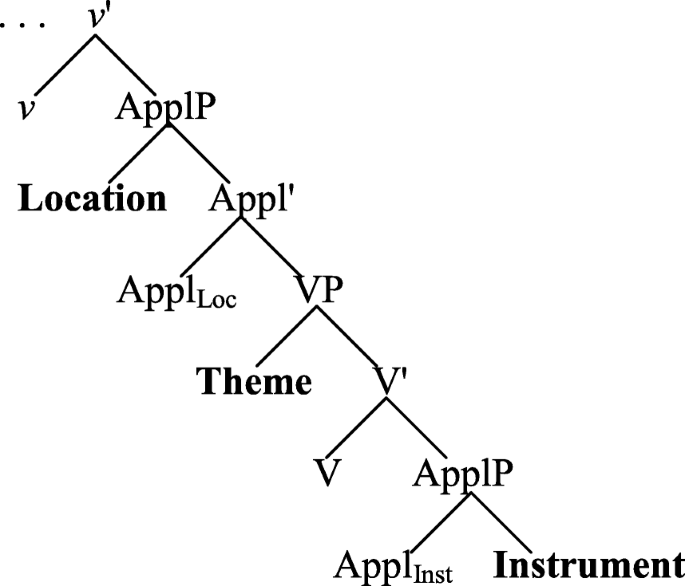

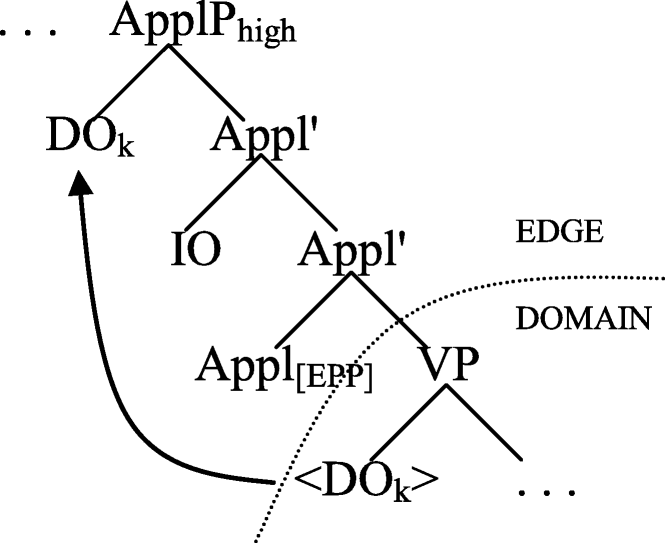

To work out the details of our proposal, first, consider the following phasal analysis of the high-low dichotomy of applicatives entertained in McGinnis (2001, 2003): Given that VP constitutes the domain of a phase (cf. Chomsky 2001), a high applicative projection counts as a phase by virtue of hosting a phasal EPP feature, as illustrated in (38):

-

(38)

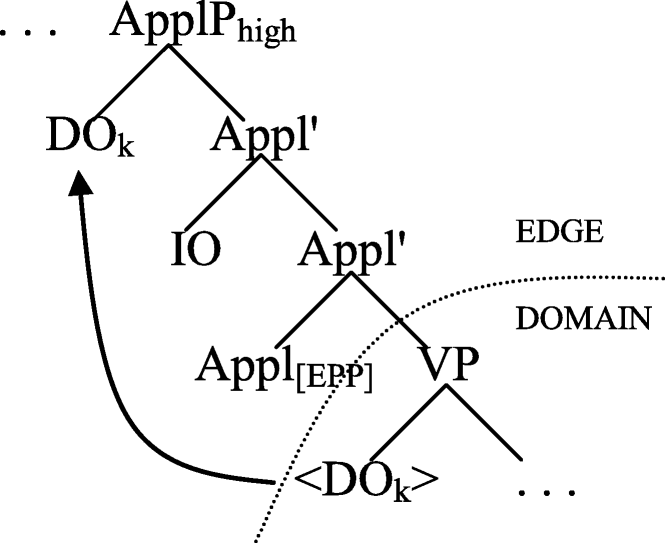

The IO is already on the edge of the ApplP phase, so it is free to raise further. The DO, on the other hand, can check an optional EPP feature, as is the case with Kinyarwanda benefactive applicatives in (11a) and (11b), hence gaining access to the “escape hatch” on the edge position. As a result, both IO and DO may undergo passivization. By contrast, a low applicative projection merges below VP and is never phasal, as visualized below:

-

(39)

In this scenario, only the IO may be passivized by raising to the edge of vP phase, as is the case with Kinyarwanda instrumental applicatives in (12a) and (12b). This is because there is no escape hatch on the low applicative projection, and it is impossible for the DO to cross over the IO due to the Minimal Link Condition.

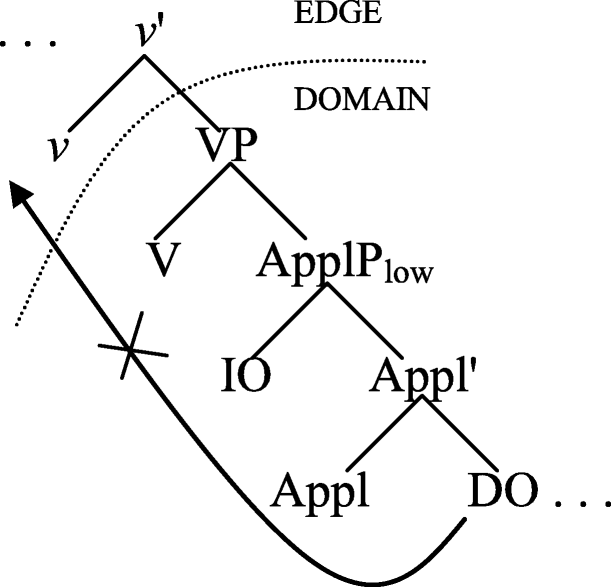

This phase-theoretic account of applicatives, however, does not readily explain the asymmetry between Mandarin inner affectives and benefactives. To do this, we have to look into a more complicated case of multiple applicatives discussed in McGinnis and Gerdts (2003): They point out that, when a locative applicative combines with an instrumental applicative in Kinyarwanda, as in (40), it is the locative argument, but not the Theme and the Instrument, that is subject to passivization, as evidenced by the contrast between (41a) and (41b) and (41c):

-

(40)

úmwáalímu__y-a-andik-iish-ijé-ho__ikíbáho__imibáre__íngwa.

teacher__he-Pst-write-Inst-Asp-Loc__blackboard__math__chalk

The teacher wrote math on the blackboard with chalk.

-

(41)

-

a.

ikíbáho__cy-a-andik-iish-ij-w-é-ho__imibáre__íngwa. [Location passivized]

blackboard__it-Pst-write-Inst-Asp-Pass-Asp-Loc__math__chalk

On the blackboard was written math with chalk.

-

b.

* imibáre__y-a-andik-iish-ij-w-é-ho__ikíbáho__íngwa. [*Theme passivized]

math__it-Pst-write-Inst-Asp-Pass-Asp-Loc__blackboard__chalk

-

c.

* íngwa __y-a-andik-iish-ij-w-é-ho__ikíbáho__imibáre.[*Instrument passivized]

chalk__it-Pst-write-Inst-Asp-Pass-Asp-Loc__blackboard__math

-

a.

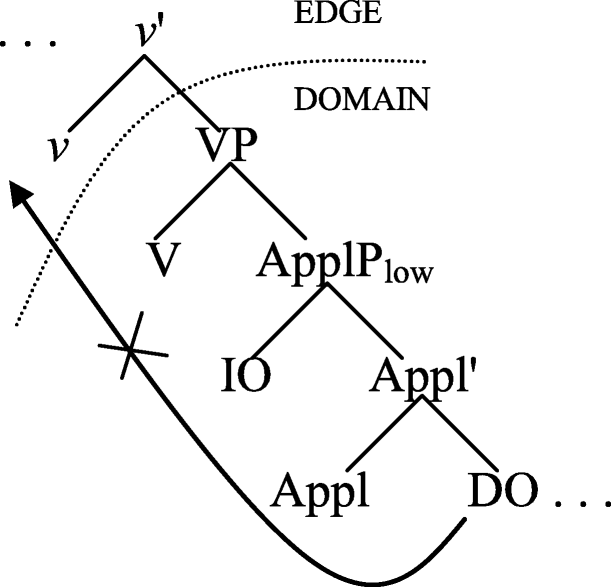

The assumption is that the locative argument ikíbáho ‘blackboard’ merges above VP and is thus able to escape from the edge of vP. Crucially, here, the locative applicative differs from its benefactive counterpart in not possessing a phasal EPP feature. By contrast, the Instrument íngwa ‘chalk’ merges below the Theme imibáre ‘math’ within VP. Both arguments are prevented from raising further, since the locative applicative projection above VP is not phasal, providing no escape hatch to this end, as illustrated in the following diagram:

-

(42)

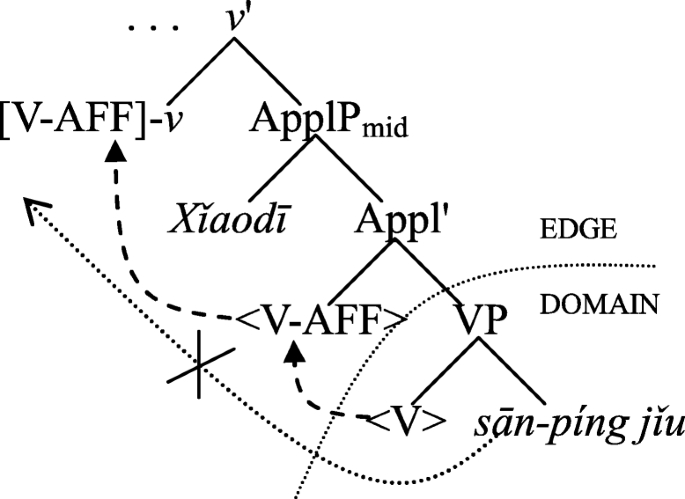

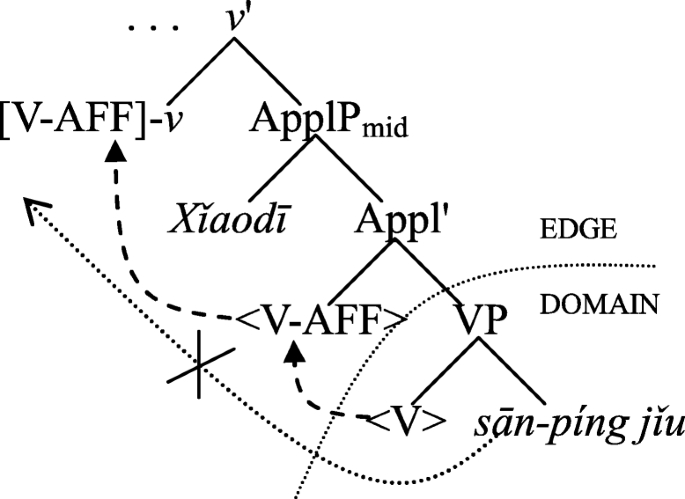

3.3 Inner affectives as middle applicatives

In light of the phase-theoretic account, one may well assimilate Mandarin inner affectives to Kinyarwanda locatives in syntactic terms: They are not high applicatives, as the real one is upstairs in the inflectional layer, as is the case with Kinyarwanda benefactives, or even higher up in the left periphery, as is the case with outer affectives. On the other hand, they are not low applicatives, either. In the case of Kinyarwanda, it is instrumental applicatives that reside at the bottom of the syntactic hierarchy. In the case of Mandarin, the inner benefactive construction may fill the gap, where neither IO nor DO may undergo passivization. We may therefore place inner affectives such as (27) in a “middle” applicative projection in-between v and V, which is non-phasal and headed by an implicit light verb AFF, as sketched below:

-

(43)

Consequently, it is possible to passivize the Affectee Xǐaodī in the Spec position, as we have seen in (28a). On the other hand, the Theme sān-píng jǐu ‘three bottles of wine’ can neither cross over the Affectee argument nor find an escape hatch on ApplPmid. (28b) is thus correctly ruled out.

4 Double unaccusatives as middle applicatives

Given our classification of applicativity, it would be interesting to see if it has a wider range of application. For one thing, there is yet another kind of “concealed” affectives in Mandarin, which are often dubbed as double unaccusatives (cf. Chappell 1999), as exemplified by (44):

-

(44)

阿Q跑了老婆。

ākīu__pǎo-le__lǎopó

Akiu__run-Inc__wife

Akiu’s wife ran away on him.

It has long been established in the literature that the double accusative construction involves affectedness of some sort (cf. Pan 1997; Tsai 蔡維天 2016, among others). Under this view, (44) would mean “Akiu was affected by the event (his) wife ran away”, and the subject is characterized as an Affectee accordingly.Footnote 3

To dig out the underlying properties of this peculiar construal, let us apply the usual applicativity tests first: First, double unaccusatives fail the transitivity test in not being able to take an unergative predicate, as in (45):

-

(45)

* 阿Q在跑老婆。

ākīu__zài-pǎo__lǎopó

Akiu__Prg-run__wife

Moreover, both the Affectee and the Theme 老婆 lǎopó ‘wife’ cannot undergo passivization, as in (46a) and (46b), behaving more or less in line with low applicatives:

-

(46)

-

a.

* 老婆被阿Q跑了。

lǎopó__bèi__ākīu__pǎo-le

wife__BEI__Akiu__run-Inc

-

b.

* 阿Q被跑了老婆。

ākīu__bèi__pǎo-le__lǎopó

Akiu__BEI__run-Inc__wife

-

a.

This similarity, however, could result from the fact that passives and unaccusative share the same characteristics of not having an external argument. As a result, no argument in a double unaccusative can be further passivized.

In terms of semantics, the affectivity is by nature a relation holding between an individual and an event. Furthermore, the possession between the Affectee Akiu and the Theme 三頭牛 sān-tóu níu ‘three cows’ is static rather than directional, as in (47a), and it can be canceled in appropriate contexts (e.g., Akiu is only a cowboy rather than the owner of the three cows),Footnote 4 as evidenced by (47b):

-

(47)

-

a.

阿Q跑了三頭牛。

ākīu__pǎo-le__sān-tóu__níu

Akiu__run-Inc__three-CL__cow

(His) three cows ran away on Akiu.

-

b.

? 阿Q跑了[三頭小D的牛]。

ākīu__pǎo-le__[sān-tóu__xǐaodī__de__níu]

Akiu__run-Inc__[three-CL__Xiaodi__Poss__cow]

Xiaodi’s three cows ran away on Akiu.

-

a.

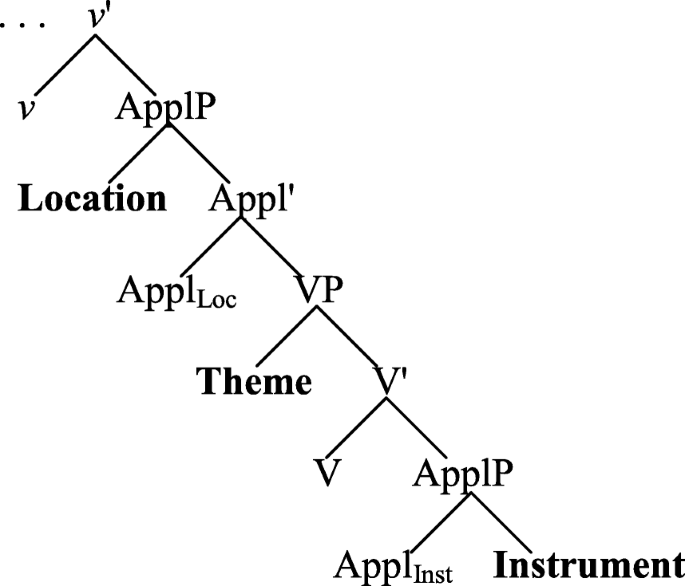

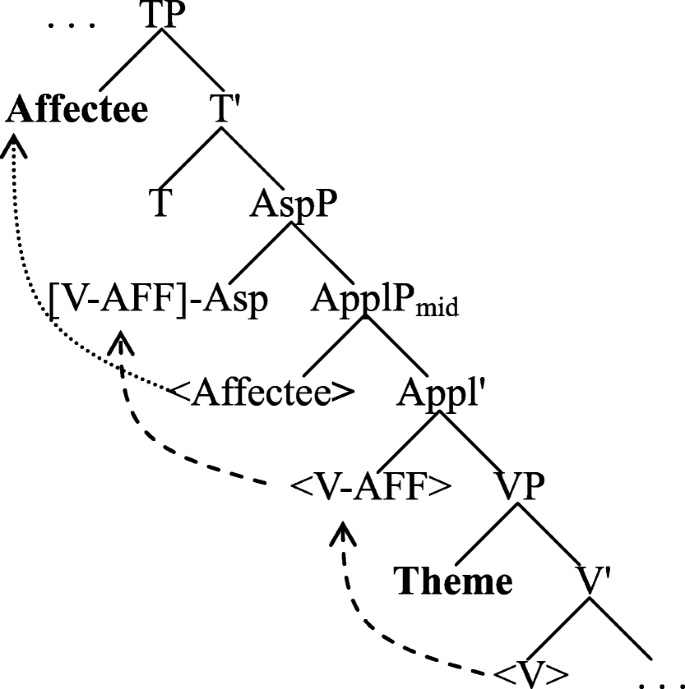

We can thus conclude from the mixed test results presented above that double unaccusatives are actually middle applicatives in disguise, whose derivation can be visualized in the following diagram:

-

(48)

So far, we have a three-way distinction of Mandarin affectives and benefactives in terms of their syntactic distribution and semantic/pragmatic interpretations, as summarized in Table 1.

That is, high applicatives are associated with the CP phase, and they are involved in the arrangement of the information structure. Middle applicatives are associated with the vP phase; they are therefore involved in the arrangement of the event structure. Finally, low applicatives are associated with the lower VP shell, which are involved in the arrangement of the argument structure. The topography of Mandarin applicatives can then be visualized as in the following topography of Mandarin applicatives (irrelevant details omitted):

-

(49)

According to this view, gěi benefactives merge to the peripheral area of vP as a PP adjunct (cf. (23a) and (23b)). They may in turn evolve into gěi affectives on the complementizer layer. The lexical layer, on the other hand, contains an implicit applicative head which can either merge above VP, introducing inner affectives and double unaccusatives, or merge below VP, licensing the inner benefactive construals.

Note that it is also possible to implement our insight in a slightly different way: One may think of the distribution of Chinese applicatives as two layers of affective-benefactive construals: Each layer involves a high-low pair of applicatives, as illustrated in Table 2.

Here, the distinction cuts across gěi applicatives above vP and unmarked applicatives down below. Consequently, middle applicative are split into two classes: The unmarked one is situated below vP, hosting an Affectee argument, whereas the marked one projects above vP, hosting a Beneficiary argument. This alternative runs into difficulties when we take seriously the PP status of gěi benefactives (which therefore should not have an independent applicative projection) but has the advantage of accommodating a variety of applicative construals from Chinese dialects which does not allow the pseudo double object construction (cf. Tsai et al. 2008; Tsai 2017). Since the analysis of dialectal variations is well beyond the scope of this paper, we will leave the choice open here.

5 Concluding remarks

All the findings presented above point to the conclusion that we need at least a three-way distinction of applicatives in terms of their structural height, as sketched below:

-

I.

High applicatives: associated with the CP phase/left periphery

→ involved in the arrangement of the information structure

-

II.

Middle applicatives: associated with the vP phase/vP periphery

→ involved in the arrangement of the event structure

-

III.

Low applicatives: associated with the lower VP shell

→ involved in the arrangement of the argument structure

A cross-linguistic study of Chinese dialects further reveals three things: First, there is a clear path for high applicatives to develop even higher applicatives along syntactic projections, all the way to the left periphery. There is also a strong tendency for a Beneficiary to evolve into an Affectee when the applied relationship has shifted from the individual level to the eventual or even propositional level. Secondly, there is a plethora of “concealed” affective construals which border on the syntax of low applicatives, while patterning with high applicatives with respect to their thematic-semantic properties. This hybrid nature is not at all surprising from our view on middle applicatives, since they indeed stand in-between outer affectives and inner benefactives. Finally, the syntax-semantics mapping responsible for shaping the topography of Mandarin affectives/benefactives thus presents a compelling argument for our three-way distinction of applicatives, which in turn provides a cartographic perspective into the theory of argument introduction in general.

Notes

For further evidence to make this inner-outer dichotomy of affectives across Chinese dialects such as Taiwan Southern Min and Sixian Hakka, see Tsai (2017).

It is worthwhile to note that this form of “transtivization” is actually possible in Old Chinese, as exemplified below:

-

(i)

孔明哭周瑜。

kǒngmíng__kū__zhoōyǘ

Kongming__cry__Zhouyu

Kongming cried for Zhouyu.

This indicates that Old Chinese applicative construals may cling to the high side, which observation also applies to instrumental, comitative, purposive, locative, affective, and putative construals in general.

-

(i)

Alternatively, (44) can also be understood something like “Akiu underwent the event (his) wife ran away,” where the subject is identified as an Experiencer. See Huang (2007) for a lexical analysis of double unaccusatives along this line.

There is an exception to our observation above: That is, when the Affectee and the Theme are in an inalienable or kinship relation, as in (ia) and (iia), the static possession cannot be canceled, as illustrated by (ib) and (iib):

-

(i)

-

a.

伍子胥白了頭髮。

wúzǐxǖ__bái-le__tóufǎ

Wuzixu__white-Inc__hair

(His) hair became white on Wuzixu.

-

b.

* 伍子胥白了[夫差的頭髮]。

wúzǐxǖ__bái-le__[fūchāi__de__tóufǎ]

Wuzixu__white-Inc__[Fuchai__Poss__hair]

-

a.

-

(ii)

-

a.

阿Q死了老婆。

ākīu__sǐ-le__lǎopó

Akiu__die-Inc__wife

(His) wife died on Akiu.

-

b.

* 阿Q死了[小D的老婆]。

ākīu__sǐ -le__[xǐaodī__de__lǎopó]

Akiu__die-Inc__[Xiaodi__Poss__wife]

-

a.

There are two factors to consider here: First, (ib) and (iib) may be ruled simply because the object position of an unaccusative cannot host a definite DP. Secondly, it may also be the case that the possession in question is intrinsic to a body-part or husband-wife relation and has nothing to do with the entailment associated with the structural semantics of applicatives.

-

(i)

Abbreviations

- 1S:

-

First-person singular

- AFF:

-

Affective

- Appl:

-

Applicative

- Asp:

-

Aspect

- CL:

-

Classifier

- Cl:

-

Clitic pronoun

- DO:

-

Direct object

- eth.dat.:

-

Ethic dative

- Eva:

-

Evaluative

- Exp:

-

Experiential aspect

- Inc:

-

Inchoative aspect

- IO:

-

Indirect object

- Loc:

-

Locative

- Pass:

-

Passive

- Poss:

-

Possessive

- Prf:

-

Perfective aspect

- Prg:

-

Progressive aspect

- Pst:

-

Past

- Top:

-

Topic

- TP:

-

Tense phrase

- vP:

-

Light verb phrase

References

Bresnan, Joan, and Lioba Moshi. 1990. Object asymmetries in comparative Bantu syntax. Linguistic Inquiry 21(2):147–185.

Buell, Leston. 2003. Introducing arguments above the agent: The case of Zulu locative applicatives. In WCCFL 22 proceedings, ed. Mimu Tsujimura and Gina Garding, 109–122. Somerville: Cascadilla Press.

Catsimali, Georgia. 1989. Genikes pu prosdiorizun ti rimatiki frasi/protasi. In Proceedings of the 9th Annual Meeting of the Department of Linguistics, Faculty of Philosophy, Aristotelian University of Thessaloniki, 257–275. Thesaloniki: Kyriakides Publications.

Chappell, Hilary. 1999. The double unaccusative in Sinitic languages. In External possession, ed. Doris L. Payne and Immanuel Barshi, 195–228. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Chomsky, Noam. 2001. Derivation by phase. In Ken Hale: A life in language, ed. Michael Kenstowicz, 1–52. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Cinque, Guglielmo. 1999. Adverbs and functional heads. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Cuervo, Maria C. 2003. Datives at large. PhD dissertation. Cambridge: MIT.

Georgala, Effi, Waltraud Paul, and John Whitman. 2008. Expletive and thematic expletives. In Proceedings of WCCFL-26, ed. Charles Chang and Hannah Haynie, 181–189. Somerville: Cascadilla Proceedings Project.

Harley, Heidi. 2002. Possession and the double object construction. Yearbook of Linguistic Variation 2(1): 29–68.

Hole, Daniel. 2006. Extra argumentality—Affectees, landmarks, and voice. Linguistics 44(2): 383–424.

Huang, C.-T. James. 2007. Unaccusativity, ditransitives and extra-argumentality. Paper presented in EACL-5, Leipzig.

Jaeggli, Osvaldo. 1982. Topics in Romance syntax. Dordrecht: Foris.

Marantz, Alec. 1984. On the nature of grammatical relations. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Marantz, Alec. 1993. Implications of asymmetries in double object constructions. In Theoretical aspects of Bantu grammar, ed. Sam Mchombo, 113–150. Stanford: CSLI Publications.

McGinnis, Martha. 2001. Variation in the phase structure of applicatives. Linguistic Variation Yearbook 1(1): 105–146.

McGinnis, Martha. 2003. Lethal ambiguity. Linguistic Inquiry 35(1): 47–95.

McGinnis, Martha, and Donna B. Gerdts. 2003. A phase-theoretic analysis of Kinyarwanda multiple applicatives. In Proceedings of the 2003 Annual Conference of the Canadian Linguistic Association, ed. Sophie Burelle and Stanca Somesfalean, 154–165. Montreal: Départment de linguistique et de didactique des langues, Université du Québec à Montréal.

Michelioudakis, Dimitris, and Ioanna Sitaridou. 2008. The ethic dative in Modern Greek and Romance. Paper presented at the 29th Annual Meeting of the Department of Linguistics, Aristotelian University of Thessaloniki.

Pan, Haihua. 1997. Lexical mapping theory and its application in Chinese. Modern Foreign Languages 4: 1–16.

Perlmutter, David. 1971. Deep and surface structure constraints in syntax. New York: Holt, Reinhart and Winston.

Pesetsky, David. 1995. Zero syntax: Experiencers and cascades. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Pylkkänen, Liina. 2002. Introducing arguments. PhD dissertation. Cambridge: MIT.

Roberts, Ian, and Anna Roussou. 1999. A formal approach to "grammaticalization". Linguistics 37(6):1011–1041.

Rizzi, Luigi. 1997. The fine structure of the left periphery. In Elements of grammar, ed. Liliane Haegeman, 281–338. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Shu, Chih-Hsiang. 2008. Sentential adverbs and information structure (Unpublished manuscript). Stony Brook: Stony Brook University.

Tsai, W.-T. Dylan. 2017. On split affectivity in Chinese. Tsing Hua Journal of Chinese Studies 47(2): 407–432.

Tsai, W.-T. Dylan, Shengli Feng, and C.-T. James Huang. 2008. On the origin of Chinese affective constructions. Paper presented at The Past Meets the Present: A dialogue between historical linguistics and theoretical linguistics, Academia Sinica, Taiwan.

Tsai, W.-T. Dylan 蔡維天. 2016. On the distribution and interpretation of inner and outer light verbs in Chinese 論漢語內、外輕動詞的分佈與詮釋. Linguistic Sciences 語言科學 15(4): 362–376.

Zhang, Niina N. 1998. Argument interpretations in the ditransitive construction. Nordic Journal of Linguistics 21(2): 179–209.

Acknowledgements

This paper benefits greatly from discussion with Lisa Cheng, Juiyi Chung, Shengli Feng, James Huang, Seng-hian Lau, Jianming Lu, Martha McGinnis, Norvin Richards, Tianqi Sun, Sze-Wing Tang, Barry Yang, and Helen Yang. Special thanks to Tim Shi for his kind encouragement over the years.

Funding

The research leading to this article is sponsored by the Chiang Ching-kuo Foundation for International Scholarly Exchange (“A Comparative Syntactic Study of Affected Arguments in Mandarin and Taiwanese”), by the Research Center for Humanities and Social Sciences of National Tsing Hua University (“A Cross-linguistic Study of Argument-introducing Strategies”), and by the National Science Council of Taiwan (NSC 100-2911-I-007-001).

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The author read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares that he has no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Tsai, WT.D. High applicatives are not high enough: a cartographic solution. lingua. sin. 4, 2 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40655-018-0034-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40655-018-0034-y