Abstract

With the increasing use of structures with adhesive bonds at the industrial level, several authors in the last decades have been conducting studies concerning the behaviour and strength of adhesive joints. Between the available strength prediction methods, cohesive zone models, which have shown good results, are particularly relevant. This work consists of a validation of cohesive laws in traction and shear, estimated by the application of the direct method, in the strength prediction of joints under a mixed-mode loading. In this context, scarf joints with different scarf angles (α) and adhesives of different ductility were tested. Pure-mode cohesive laws served as the basis for the creation of simplified triangular, trapezoidal and exponential laws for all adhesives. Their validation was accomplished by comparing the numerical maximum load (Pm) predictions with the experimental results. An analysis of peel (σ) and shear (τ) stresses in the adhesive layer was also performed to understand the influence of stresses on Pm. The use of the direct method allowed obtaining very precise Pm predictions. For the geometric and material conditions considered, this study has led to the conclusion that no significant Pm errors are incurred by the choice of a less appropriate law or by uncoupling the loading modes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The use of adhesive bonds in the aerospace, aeronautical and automotive industries, among others, has assumed a high preponderance to the detriment of conventional joining methods such as riveting, bolting, brazing and welding. In fact, adhesive bonds offer several advantages such as the reduction of stress concentrations, good response to fatigue stresses, ability to bond dissimilar materials and lightness of structures. However, they also present some limitations, namely the difficulty of disassembly, high cure times (in some cases) and limited temperature and humidity conditions [1]. The strength and behaviour of adhesive bonds depends on several factors, namely the type of adhesive used, the material of the adherends, the joint configuration and dimensional factors, such as the overlap length (LO) and the adhesive and adherends’ thickness (tA and tP, respectively). There are several types of joint geometries, although the most common are single-lap, double-lap and scarf [2,3,4,5]. Scarf joints are modified butt joints that are more time-consuming to fabricate (i.e., they require milling operations). This type of joint, when loaded, has the ability to keep the axis of loading aligned with the joint [6]. Besides that, it allows a practically constant stress distribution when manufactured with an optimized value of α. Because of this, scarf joints are popular to join composite parts [7]. However, this joint type fails to work under bending, because this loading induces cleavage stresses in the adhesive [1].

Over the years, reliable and accurate strength prediction techniques were developed. Two distinct approaches can be followed: analytical and numerical. The analytical techniques are able to easily obtain the stress state in bonded structures due to assuming simplifying assumptions in terms of joint geometry, loading and boundary conditions, allowing to obtain an explicit analytical solution for the behaviour in the elastic domain [8, 9]. Nowadays, numerical methods are often preferred over analytical ones, since they overcome some limitations of the analytical methods, such as the possibility to include some effects such as non-linearity of the adhesive and adherends, or to consider geometrical non-linearities [10]. The most common numerical method applied to adhesive bonds is CZM, as a modification of the conventional continuum-based finite element method (FEM) formulation [11, 12]. The extended finite element method (XFEM) is a more recent technique that has showed promising results in the simulation of bonded joints [13, 14]. CZM has been extensively used in the simulation of the structures’ behaviour until failure, since it allows to include in the numerical models the possibility of multiple failure paths in different regions of the materials or between interfaces, which is very helpful for adhesive joints [15]. CZM laws are based on a relationship between the cohesive stresses in tension (tn) and shear (ts) with the relative displacements in tension (δn) and shear (δs) that link homologous nodes of the cohesive elements [16]. The work of Rocha and Campilho [17] analysed the effect of using different CZM conditions in modelling single-lap joints under a tensile loading. The following analyses were made: variation of the CZM laws’ elastic stiffness, different mesh refinements in the crack paths, study of the adherends’ element type, and evaluation of several damage initiation and growth criteria. It was shown that CZM is suitable for static strength prediction of bonded joints, and the best set of numerical conditions for this purpose was pointed out.

The main parameters of the CZM laws to introduce in the numerical models are the cohesive strengths in tension (t 0n ) and shear (t 0s ), and the critical values of tensile and shear strain energy release rate (GIC and GIIC, respectively). The estimation of the referred cohesive parameters (GIC, GIIC, t 0n and t 0s ) can be performed by the property identification technique, the inverse method and the direct method. All these methods usually rely on double-Cantilever Beam (DCB) or End-Notched Flexure (ENF) tests. The property identification technique consists of the isolated definition of the cohesive laws parameters through appropriate tests, while the inverse method relies on estimating at least one parameter by an iterative adjustment procedure between experimental data of a given test and its FEM prediction [18]. In a typical inverse method approach, GIC and GIIC are estimated by tests such as the DCB and ENF, respectively, using a suited method or theory. Then, the obtained values of GIC and GIIC are used to build CZM laws in pure modes (tension and shear), while typical values of the parameters t 0n and t 0s are initially assumed. In this process, the elastic stiffness of the tensile and shear CZM laws is usually directly inferred from the Young’s modulus (E) and shear modulus (G), respectively, both divided by tA. These CZM laws are next applied to numerical models replicating the fracture tests, created with the same dimensions of the real specimens. Following, for the definition of t 0n and t 0s , an adjustment is undertaken between the numerical and experimental load–displacement (P–δ) curves, producing a cohesive law that can accurately reproduce the adhesive layer in the respective loading mode. The assembly of a mixed-mode CZM from this information, including criteria for damage initiation and growth prediction, enables to design bonded structures under arbitrary loadings. This method was applied in the work of Moreira and Campilho [6], to assess the strength improvement of bonded scarf repairs in aluminium structures with distinct external reinforcements, using the adhesive Araldite® 2015 (Araldite® from Huntsman, Basel, Switzerland). Fairly accurate numerical approximations were attained, but generally with slightly smaller Pm values compared to the experiments. The maximum deviation attained was 20.2%, for a specific repair configuration. This allowed to conclude that the used numerical technique and respective inverse method for CZM laws establishment simulate with reasonable accuracy the behaviour of the bonded repairs. The direct method allows estimating the complete cohesive law for a given material or interface by differentiating the tensile strain energy release rate (GI) or the shear strain energy release rate (GII) with respect to δn or δs, after the polynomial fitting to the most precise degree. With this procedure, the tensile and shear cohesive laws can be obtained, for example, from DCB and ENF tests, respectively [19]. The accuracy of the obtained cohesive laws can be verified by comparing the P–δ curves resulting from CZM laws simulation with the respective test results. A few works are available that estimate the CZM laws of adhesives by the direct approach from either pure or mixed-mode fracture tests. For instance, in the work of Ji et al. [20], the DCB specimen was used to estimate the CZM laws in tension of a brittle epoxy adhesive by a direct method. A clear tendency was achieved as a function of tA: (1) GIC increases up to tA = 1 mm and (2) t 0n is highest for tA = 0.09 mm and slowly reduces by increasing tA up to equalling the bulk strength of the adhesive. Leffler et al. [21] used the ENF specimen to calculate GIIC and the CZM law in shear of an epoxy adhesive by the direct method. Constant displacement rate and constant shear deformation rate assumptions were compared, giving identical estimations of t 0s . On the other hand, higher GIIC was found by testing at constant displacement rate. Jumel et al. [22] directly addressed the mixed-mode CZM laws of adhesive layers by using the mixed-mode bending (MMB) test. Gheibi et al. [23] proposed a new mode-dependent CZM for the simulation of adhesive joints, estimated by the direct method. This was accomplished by using DCB and ENF tests for the direct experimental extraction of the CZM laws (tensile and shear, respectively). The obtained laws were used to implement a simplified Park–Paulino–Roesler CZM. After deriving the mixed-mode parameters, the proposed model was implemented in Abaqus® (Dassault Systèmes, Vélizy-Villacoublay, France) and validated against experimental results of single-lap joints and scarf joints. The accuracy of the developed mixed-mode CZM model for was confirmed for different mode-mixity conditions. The direct method was also applied in the work of Carvalho and Campilho [24] to validate, with a mixed-mode geometry, tensile and shear cohesive laws obtained in pure mode. With this purpose, single lap-joints with different LO and adhesives were considered, ranging from brittle to ductile. To apply the direct procedure, the originally obtained pure-mode CZM laws were simplified to parameterized triangular, trapezoidal and linear–exponential CZM laws in order to evaluate which form fits better with the behaviour of each adhesive. The joints bonded with the brittle Araldite® AV138 were best modelled by a triangular CZM law shape, mainly due to the adhesive’s brittleness, while the Araldite® 2015 results were best fitted with a trapezoidal CZM, considering that this adhesive has some degree of ductility. The behaviour of the highly ductile Sikaforce® 7752 (Sikaforce® from Sika®, Baar, Switzerland) was more accurately reproduced by a trapezoidal CZM law. However, irrespectively of the adhesive, for the analysed joint geometry (single-lap joints), the errors incurred by applying a less suitable CZM law shape for a given adhesive were always under 10%.

This work consists of a validation of cohesive laws in traction and shear, estimated by the application of the direct method, in the strength prediction of joints under a mixed-mode loading. In this context, scarf joints with different α values and adhesives of different ductility were tested. Pure-mode cohesive laws served as the basis for the creation of simplified triangular, trapezoidal and exponential laws that were tested for each of the adhesives. Their validation was accomplished by comparing the numerical Pm predictions with the experimental results. An analysis of σ and τ stresses was also performed in the adhesive layer in order to understand the influence of stresses on the joints’ strength.

Methods

Experimental

Adherends and adhesives

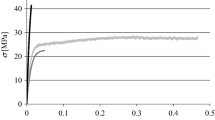

The adherends used in the DCB, ENF and scarf specimens consisted of the AW6082-T651 aluminium alloy. This material is obtained through artificial aging, at a temperature of 180 °C, and it was selected due not only to its attractive mechanical properties, but also to the wide field of structural applications in extruded and laminated products. It was characterized in previous studies [25], where the following properties were defined: tensile strength of 324.00 ± 0.16 MPa, E of 70.07 ± 0.83 GPa, yield stress of 261.67 ± 7.65 MPa and tensile failure strain of 21.70 ± 4.24%. The stress–strain (σ–ε) curves of this alloy were experimentally obtained according to the standard ASTM-E8M-04 [25]. The adhesives selected for this work cover a range of ductility from low (brittle) to high. The adhesives were the Araldite® AV138, which is a brittle epoxy adhesive, the Araldite® 2015, an epoxy adhesive with moderate ductility, and the Sikaforce® 7752, a highly ductile polyurethane adhesive. Details regarding these adhesives can be found in previous studies [26,27,28]. The DCB test was used to extract GIC and the ENF test for GIIC. The collected data of the adhesives is given in Table 1.

Joint geometry, fabrication and testing

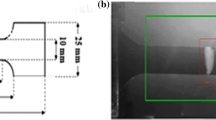

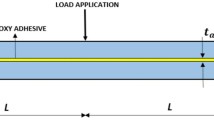

The geometry of the DCB (a) and ENF specimens (b) is shown in Fig. 1. These specimens have the following dimensions: length L = 143 mm for the DCB and mid-span L = 100 mm for the ENF, initial crack length a0 ≈ 55 mm, tP = 3 mm, tA = 0.2 mm and width B = 25 mm. The scarf joints’ geometry is depicted in Fig. 2. The scarf joint has a length (LT) of 200 mm, whilst the other dimensions are as follows: B = 25 mm, tA = 0.2 mm, tP = 3 mm and α of 3.43°, 10°, 15°, 20°, 30° and 45°. The DCB and ENF joint adherends were obtained by cutting, with a disk saw machine, strips already supplied with the desired value of B. To prepare the bonding surfaces, these were sandblasted in order to remove oxide layers, and increase surface roughness, contact area and wettability, to further improve the bonding process. After this procedure, all the adherends were subjected to a chemical passive solvent degreasing process (cleaning with acetone) in order to remove grease spots or abrasive particles [29]. With this procedure, cohesive failures of the adhesive were achieved for all specimens. For the bonding process, spacers were used to ensure a constant value of tA and also to promote the creation of the crack. In the DCB and ENF specimens, two calibrated spacers for each specimen were used: a rear one, which allows to ensure a constant tA of 0.2 mm, and a front one that, besides contributing to the constant tA, also enables creating a pre-crack. The curing of the adhesives was carried out in a prepared jig to ensure the adherends’ alignment, taking into account the manufacturer specifications. After complete cure of the adhesives, the adhesive excesses of all the samples were removed with the aid of a drill press equipped with a grinding wheel. For the scarf joints, the fabrication began by cutting the adherends from aluminium strips with dimensions of 140 mm (length), 25 mm (width) and 3 mm (thickness). After this process, one of the adherends’ ends was milled in a milling machine to obtain the respective α. Following, the scarf surfaces were prepared for bonding identically to the DCB and ENF specimens. Bonding and curing were undertaken using a jig that guaranteed the correct spacing between adherends, to promote the desired tA.

All joints were tested in the Shimadzu AG–X test equipment (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan), with a 100 kN load cell. For the DCB and scarf tests, the machine was in the generic configuration to perform tensile tests. For the ENF tests, it was adapted to apply a three-point bending flexure loading. The equipment is connected to a data acquisition system that records the test time, applied load and grips’ displacement. These values will be used to plot the P–δ curves and perform all required data analysis. All the tests were carried out under conditions of room temperature and humidity. The test velocity was 1 mm/min. Five specimens were tested for each condition.

Direct method for the DCB and ENF tests

The J-integral is suitable for the non-linear elastic behaviour of the materials, but remains applicable for monotonic plastic loads. Based on the fundamental expression for J defined by Rice [30], it is possible to derive an expression for GI applied to the DCB specimen, from the concept of energy force and also by the beam theory for this particular geometry, as follows

where Pu represents the load per unit width applied at the specimen ends, a is the crack length, Ex is the Young’s modulus of the adherends, θo is the relative rotation of the adherends at the crack tip, and θp is the relative rotation of the adherends measured at the loading line. Figure 3 describes the direct method application to the tensile (a) and shear (b) cohesive law estimation, with emphasis to the parameters δn, θo and θp (DCB test) and δs (ENF test), necessary by the direct method, the relative displacement at t 0n (expressed as δ 0n ) and at t 0s (expressed as δ 0s ), and the tensile and shear relative displacements at failure (δ fn and δ fs , respectively). The tn(δn) curve can easily be obtained by differentiating Eq. (1) with respect to δn. In the work of Constante et al. [31], an experimental work was carried out with the objective of estimating GIC of adhesive joints by the DCB test. An optical measurement method was developed to evaluate δn and θo, to apply the J-integral. It is also possible to apply a similar J-integral technique for GIIC estimation using the ENF test. The proposed GII evaluation expression results from the use of alternative integration paths to extract the J-integral, defined by Rice [30], resulting in the following closed-form expression for the calculation of GII

The ts(δs) curve or shear cohesive law of the adhesive layer is thus estimated by fitting the resulting GII–δs curve, and differentiation with respect to δs. Leitão et al. [32] presents the full details regarding the description of the direct method applied to the ENF specimen, as well as the algorithm to estimate δs.

Numerical

CZM theory

In this work, approximated triangular, trapezoidal and linear–exponential laws were tested to reproduce the experimentally obtained CZM laws by the direct method and further undergo the validation process by comparing with experiments. In these three models (further addressed as independent-mode models), the tensile and shear behaviours are uncoupled. The three CZM shapes are depicted in Fig. 4. In this figure, δ sn and δ ss are the tensile and shear stress softening onset displacements of the trapezoidal CZM law, respectively. The values δ fn and δ fs are internally calculated by the software from the knowledge that the area under the CZM laws is equal to GIC (tensile law) or GIIC (shear law). A mixed-mode triangular CZM model is also considered for comparison. In all models, the initial part of the CZM laws is defined by the relation between the current stresses and strains in tension and shear (subscripts n and s, respectively) [33]

The strain vector includes the tensile (εn) and shear strain (εs). The approximation of making Knn = E, Kss = G, Kns = 0 is commonly accepted for the simulation of thin adhesive layers [25]. In the independent-mode models, after t 0n and t 0s , the softening portions of the CZM law are based on the establishment of a damage variable (dn for tension or ds for shear), such that [33]

where t undn and t unds are the current values of tn and ts, respectively, without stiffness loss from the initial behaviour. The damage variable ranges between dn,s = 0 (in the elastic portion of the CZM law) and dn,s = 1 (at the end of the softening process). More details on the definition of this variable are available in Ref. [27]. The definition of dn,s for all CZM law shapes is available in the Abaqus® documentation [33]. The formulae for the linear–exponential law requires defining the parameter αexp to specify the softening evolution with δn,s (α = 0 gives a triangular law and increasing αexp progressively decreases stresses in the softening part of the curve). A value of αexp = 7 was considered in this work. Also, as previously mentioned, no coupling criteria was applied, i.e., the tensile and shear modes are independent in the simulations during damage growth, since this is the available method available in Abaqus®, which can be readily applied by users with less experience and knowledge. Naturally, the employed simplification can only be applied if the predictive capabilities of the method are not compromised. This was checked in a previous work [24], in which uncoupled-modes results are compared with those using a mixed mode triangular CZM, with positive results. In the triangular mixed-mode model, a quadratic stress criterion was considered for damage initiation and a linear energetic criterion was used for damage growth. More details about this model can be found in Ref. [25].

Implementation of the model in Abaqus®

The pure mode CZM laws in tension (tn–δn) and shear (ts–δs), obtained by the direct method, were validated in Abaqus®, considering two-dimensional (2D) FEM models of the scarf joints and a geometrically non-linear failure analysis [34]. Two distinct models were built: one for the elastic stress analysis and the other for the damage variable (SDEG) analysis and for the CZM strength predictions. Considering the bondline stress analysis, continuum FEM elements were applied in the adhesive layer and adherends, while for the strength predictions the adhesive layer was modelled by one layer of CZM elements in the thickness direction. The created models for stress analysis purposes were meshed throughout by 4-node plane-strain elements (CPE4 from Abaqus®). For the strength analysis, the adherends were modelled as continuum elasto-plastic parts with CPE4 elements, while the adhesive layer’s behaviour was characterized by a single row of CZM elements, used to connect both adherends (COH2D4 4-node cohesive elements from Abaqus®) [27]. Figure 5 represents the mesh details for a scarf joint example with α = 45° used for strength prediction. For both analysis types, the adhesive layer was meshed with CZM elements’ with size of 0.1 mm (length) × 0.2 mm (thickness). Assuming this procedure, the total number of CZM elements increases with the α reduction. In order to minimize the computational effort, a mesh growth refinement was applied (bias ratio) [35] in the adherends’ length direction, from the specimen’s ends to the beginning of the scarf region. To simulate the real conditions of the experimental tests, as boundary conditions, the joints were clamped at one end, and pulled in tension on the opposite end, while orthogonally restrained.

Results and discussion

CZM law estimation by the direct method

In order to obtain the CZM laws for each one of the adhesives with the direct method, first of all, it is necessary to estimate the GI–δn and GII–δs curves as mentioned in “0” section, respectively, with Eqs. (1) and (2). A differentiation procedure is applied to the referred curves after the polynomial fitting, to provide the complete CZM laws in each pure mode. Figure 6 represents CZM curves’ examples for each adhesive obtained from the DCB and ENF tests, all of them with the respective polynomial fitting law, considering the adhesives Araldite® AV138 (a), Araldite® 2015 (b) and Sikaforce® 7752 (c). According to Ji et al. [20], GIC and GIIC are obtained when the curves reach the steady state value of GI/GII. The adhesives in study present distinct ductility, which reflects in the different obtained values of δn/δs corresponding to GIC/GIIC. In fact, the adhesives Araldite® 2015 and Sikaforce® 7752 reveal a softening phase near GIC and GIIC for the DCB and ENF curves, respectively, due to their ductility. In this work, the DCB specimens of Fig. 6 present the following GIC (N/mm): 0.252 (Araldite® AV138), 0.437 (Araldite® 2015) and 3.420 (Sikaforce® 7752). From the ENF tested specimens presented in Fig. 6, the following GIIC values were obtained (N/mm): 0.479 (Araldite® AV138), 3.444 (Araldite® 2015) and 5.790 (Sikaforce® 7752). As a result from this work, Table 2 presents the set of GIC and GIIC values obtained for each specimen by the J-integral technique, with the average and standard deviation values for each condition. A comparison is also made with previous results obtained by the compliance-based beam method (CBBM) [18, 31, 36]. Some of the tested specimens were not considered for analysis, due to significant deviations from the average behaviour, or due to difficulties in the CZM law polynomial fitting procedure during the application of the direct method. To build the average tensile and shear CZM laws for further strength prediction of the scarf joints, the average GIC and GIIC values referred in Table 2 were considered. However, for the CZM laws, t 0n and t 0s are also required. The average values of t 0n and t 0s were used for this purpose, obtained from the differentiation procedure applied to GI–δn and GII–δs curves from the DCB and ENF tests, respectively, giving the following values (MPa): t 0n = 37.4 and t 0s = 16.8 (Araldite® AV138), t 0n = 32.9 and t 0s = 14.8 (Araldite® 2015) and t 0n = 22.0 and t 0s = 11.7 (Sikaforce® 7752). By comparing the cohesive parameters, (t 0n , t 0s , GIC and GIIC) and the values presented in Table 1 for the different adhesives, some deviations can be found. These differences regard the equivalency between t 0n and the tensile strength (σf), and also t 0s and the shear strength (τf). However, the obtained t 0n and t 0s values cannot be directly compared with the properties σf and τf, since they take into account the constraint effects caused by the adherends. On the other hand, GIC and GIIC depend on tA and tP of the test specimens which are being used for characterization [37]. Thus, in this work, the DCB, ENF and scarf geometries were defined to match as best as possible, regarding tA and tP. According to Ji et al. [20], although the cohesive parameters obtained by the direct method do not have a clear physical significance, they are able to accurately reproduce the materials’ behaviour into a macro scale view point, which is accurate. Figure 7 represents the CZM laws in tension (tn–δn) and shear (ts–δs) corresponding to the specimens of Fig. 6. It can be seen that the tensile and shear behaviour of Araldite® AV138 can be more accurately modelled with a triangular approximation, mainly due to its brittleness. On the other hand, the tensile and shear laws of Araldite® 2015 and Sikaforce® 7752 are best adjusted by trapezoidal CZM laws, due to the allowable plasticization of the referred adhesives before failure.

Stress analysis

A numerical stress analysis was initially carried out to study σ and τ stresses developing at the middle of the scarf adhesive layer, during elastic loading, as a function of the normalized scarf length x/LS (0 ≤ x ≤ LS), in which x is the coordinate tangential to the adhesive layer and LS the scarf length. Both σ and τ stresses were subjected to a normalization procedure, by dividing them by the average shear stress in the adhesive layer (τavg) for each α. In this work, only the stress distributions for the joints bonded with the Araldite® 2015 are shown. However, these stresses are also representative of the other two adhesives’ behaviour (although there are small differences in the peak stresses because of the differences in E; see Table 1). In general, it is known that the use of smaller values of α leads to higher LS and, thus, to higher joint strengths. However, it also provides longer machined lengths and required volume of adhesive [38].

Figure 8 shows σ (a) and τ (b) stress distributions for the scarf joints bonded with the Araldite® 2015, as a function of α. It was found that σ stresses are much smaller in magnitude than τ stresses for the smaller values of α, and that these progressively approach τ stresses for α = 45°, at which angle both stress components have a similar significance [39, 40]. This conclusion agrees with the theoretical analyses of references [41, 42]. The peak σ stresses found for the joints with smaller α gradually reduce by increasing this parameter. On the other hand, τ stresses keep an identical behaviour along the bond length, although peak τ stresses also tend to become more flat with the increase of α [43]. Actually, considering the scarf joint with α = 45°, τ stresses are practically constant. These results seem to indicate that smaller α have an improved behaviour because of the reduction of normalized σ stresses, although minor τ stress gradients appear for small α. Added to this, smaller α also correspond to higher LS, which should lead to larger Pm.

Damage variable analysis

This Section addresses a study of the damage variable of the CZM elements (SDEG variable in Abaqus®) across the adhesive layer, i.e. for 0 ≤ x/LS ≤ 1, to fully characterize the failure process of the scarf joints bonded with the three adhesives. The SDEG variable spans between 0 (corresponding to the elastic part of the CZM law) and 1 (or 100%, relating to failure of the CZM element). Initially, the SDEG plots of the three adhesives as a function of x/LS are presented for the instant of Pm (Fig. 9). The curves are cropped at SDEG = 0.3 to improve their visualization.

Notwithstanding the adhesive type, the highest incidence of damage in this type of joint occurs at the adhesive layer’s ends, consistently to the stress distributions presented in “Introduction” section. Oppositely, at the intermediate zone of the bond, SDEG is typically zero. Between adhesives, it was found that the stiffness and brittleness of the Araldite® AV138 makes it very sensible to the peak stresses that take place near x/LS = 0 and 1 (Fig. 8 shows this effect, although for a different adhesive), such that the span of damage, i.e., length of x/LS between SDEG = 0 and 1, is very short. The total length under damage ranges between 11.1% (α = 3.43°) and 55.0% (α = 45°) of LS, reinforcing the lack of plasticization ability of this adhesive. The shift in the adhesives’ properties, particularly the increasing elastic compliance and ductility, enables damage to spread more evenly and to reduce the gradients along the bond length. Actually, on one hand, the higher compliance of the Araldite® 2015 and Sikaforce® 7752 reduces σ and τ peak stresses which, alone, helps in spreading damage more evenly. On the other hand, the higher ductility of these two adhesives, compared to the Araldite® AV138, enables the damaged regions to keep working while the inner regions of the bond are put under loads as well. As a result, the damage lengths for these adhesives range between 65.0% (α = 45°) and 87.2% (α = 3.43°) for the Araldite® 2015 and 15.0% (α = 45°) and 78.6% (α = 3.43°) for the Sikaforce® 7752. Between adhesives, the increased compliance of the Sikaforce® 7752 is responsible for the more uniform span of damage at Pm, which ranges between 0 and ≈ 12.5% compared to 0–100% for the Araldite® AV138 and 0–43.8% for the Araldite® 2015 (maximum values, obtained for specific α). Comparing the SDEG curves between the different α, the Araldite® AV138 shows a different behaviour to the other adhesives, in the sense that smaller α results in more concentrated damage and higher SDEG gradients. This is because of its brittleness, which clearly cannot accommodate the higher σ and τ peak stresses at the overlap ends (this effect can be identified in Fig. 8, despite this figure relates to the Araldite® 2015). Since σ and τ stresses slowly become more flat with increasing α, the damage also increases towards the central region of the bond. The ductile adhesives are not affected by these peak stresses, since the damage span across the bond does not vary much with α. Nonetheless, SDEG attains higher percentile values at Pm for smaller α also due to the aforementioned differences in σ and τ peak stresses.

Discussion on the joint strength

All failures were cohesive in the adhesive layer. Figure 10 shows, as an example, the fracture surfaces for the scarf joints bonded with the Sikaforce® 7752 and α = 3.43°. Figure 11 compares the experimental Pm values of the scarf joints bonded with the three adhesives as a function of α. The obtained results showed that the mechanical behaviour of the scarf joints is highly dependent on the type of adhesive and value of α. Actually, a more stiff and brittle adhesive leads to higher peak stresses and instability in damage propagation, while a less stiff and ductile adhesive presents more uniform stress distributions and more stable damage growth during loading. This also translated into a different damage behaviour, with the SDEG variable showing abrupt variations along x/LS for the Araldite® AV138, thus concentrating along a smaller bond length. Oppositely, for the other two adhesives, due to their higher compliance and ability to undergo the plastic regime of the adhesive, the damage spreads more evenly and a larger portion of the adhesive layer is contributing to the load transfer. A difference in Pm is also evident with the decrease of α. Actually, smaller α promote an increase of stress concentrations [44] and increasing SDEG gradients along the bond length, which could be responsible for a Pm reduction. However, smaller values of α have the advantage of presenting an increasingly larger bond length and area, which cancels the peak stresses effect and results in much higher Pm values. The Pm evolution with α is typically exponential, which agrees with previous results [6]. In fact, a significant increase in strength was found for α smaller than 20°, while for bigger α the differences are minimal. In the particular case of the Araldite® AV138, there is a 67% Pm increase from α = 45° to 20°, and a 445% Pm improvement between α = 20° to 3.43°. By the same respective order, for the Araldite® 2015, these percentile Pm differences are 95% and 492% and, for the Sikaforce 7752, these are 99% and 439%. By comparing the three adhesives, the Araldite® AV138 gives the best results for all α, although it is the most brittle. Actually, the Pm variation over the Araldite® 2015 ranges from 37.4% (α = 10°) to 78.1% (α = 45°). Compared to the Sikaforce® 7752, these differences are 120.6% (α = 10°) and 182.8% (α = 30°). This behaviour is somehow different to the typical behaviour of lap-joints, in which strong yet brittle adhesives are clearly outperformed by less strong but more ductile adhesive [45]. However, in these cases, large peak stresses exist at the overlap edges, which make joints with brittle adhesive to fail prematurely, without any ability to undergo plastic behaviour and stress redistribution. On the other hand, joints with ductile adhesives manage to undergo plastic deformations in the adhesive layer after the limiting stresses are attained, which increases the average stress at failure in the bondline and, correspondingly, Pm is also higher [46]. The contrasting behaviour observed for the scarf joints tested in this work is mainly due to the much smaller stress gradients than in lap joints (Fig. 8), leading to best results with a stronger but brittle adhesive because, under these conditions, the average stress at failure is higher. These findings agree with previous results [47], relating to hybrid scarf joints between aluminium and composites. On the other hand, the adhesives’ ductility is not as important as in lap joints.

Evaluation of the different CZM law shapes

Figure 12a–c present the comparison between the experimental Pm and the respective numerical predictions for the scarf joints bonded with the adhesives Araldite® AV138, Araldite® 2015 and Sikaforce® 7752, respectively. In all cases, the mixed-mode and independent-mode formulations were considered. For the mixed-mode simulations, a triangular CZM was evaluated. For the independent-mode formulations, triangular, trapezoidal and linear–exponential simulations were tested. The CZM predictions show, disregarding the formulation and CZM law shape, a good match to the experiments for all geometric conditions and adhesives, emphasizing that the strength prediction of adhesive joints by CZM modelling using a direct method for the cohesive laws’ estimation is accurate. Moreover, this analysis showed which CZM law shape is best suited for each type of adhesive, although the differences between CZM shapes is very small. The analysis showed that this was due to a typically uniform stress state. It was also found that, as the adhesives’ ductility increases, the percentile deviation between CZM law shapes becomes smaller. The maximum differences between the mixed-mode and independent-mode formulations were 1.66% for the Araldite® AV138, 0.74% for the Araldite® 2015 and 0.68% for the Sikaforce® 7752. For all adhesives, the percentile reduction between the mixed-mode and independent-mode models also reduces with increasing α. On the other hand, previous studies revealed that, in other geometries, much higher differences can be found [24]. However, for the particular set of conditions tested in this work, the CZM law shape is irrelevant. Nonetheless, for each adhesive, a CZM formulation exists that performs slightly better than the other. The match between the independent-mode models and the mixed-mode model also depends on the adhesive type. For the Araldite® AV138, the triangular independent-mode model approaches most to the mixed-mode model. The deviations between these two formulations range from 0.1% (α = 45°) to 0.5% (α = 3.43°). For the Araldite® 2015, the trapezoidal independent-mode model gives the best match to mixed-mode model, with deviations from 0.2% for α = 45° to 0.5% for α = 3.43°. The differences are minimal between independent-mode models when using the Sikaforce® 7752. Nonetheless, the exponential model gives slightly closer values to the mixed-mode model. The obtained differences were between 0.2% for α = 45° and 0.7% for α = 3.43°.

Figure 13 represents the evolution of percentile difference between Pm for each independent model and the mixed-mode triangular model (Δ) with α, for the three tested adhesives. An overlook of the results shows that, in all cases, Δ acquires negligible values. This reinforces that, for the particular tested conditions (practically uniform stress distributions; Fig. 8), the influence of coupling the loading modes in the CZM laws has a marginal effect. The largest absolute difference between any independent-mode law and the mixed-mode triangular law were 1.66% for the Araldite® AV138 (exponential model), 0.74% for the Araldite® 2015 (exponential model) and 0.68% for the Sikaforce® 7752 (triangular model), in all cases for the smallest α. A marked tendency was found to reduce Δ with the increase of the adhesives’ ductility, although this occurs with a less extent for the Sikaforce® 7752. On the other hand, this also reflects on corresponding smaller deviations between the different independent-mode models. Inclusively, for the scarf joints bonded with the Sikaforce® 7752, the results are virtually identical. In more detail, the largest absolute deviations between the trapezoidal or exponential independent-mode laws over the triangular independent-mode law were 1.22% for the Araldite® AV138, 0.14% for the Araldite® 2015 and 0.02% for the Sikaforce® 7752, which clearly shows this trend. This reinforces the conclusions of Fig. 12, which showed that, under the testing conditions, the influence of both law shape and mode coupling is negligible. As a result, for this type of joint, mode uncoupling and any law type can be used with confidence in the strength prediction. This is also valid for the simulation of composite delaminations [48]. It should however be noted that, in joint configurations that induce higher stress gradients along the overlap, the differences due to using a less convenient CZM law shape can increase. Campilho et al. [27] attained differences in order of magnitude of 10% by simulating single-lap joints bonded with the Araldite® 2015 with a triangular CZM.

Conclusions

The main purpose of this work was the evaluation of different CZM formulations to predict the strength of adhesively-bonded scarf joints, considering the tensile and shear pure-mode laws were estimated by a direct method. Three adhesives were evaluated, whose behaviour ranged from strong and brittle to less strong and ductile. The results showed that the mechanical behaviour of the scarf joints is dependent on the type of adhesive and value of α. A more stiff and brittle adhesive leads to slightly higher peak stresses, while a more flexible and ductile adhesive gives more uniform stress distributions. Nonetheless, comparing with other joint configurations such as single-lap and double-lap, the stress distributions are much improved. Peak τ stresses along the bondline increase with the reduction of α, which negatively affects the joint strength, but the reduction of this parameter also increases exponentially LS, whose effect is much more preponderant and leads to a Pm improvement. The damage plots at Pm reflected the result of the elastic stress distributions, with maximum damage at the adhesive ends. The damage span was smallest for the Araldite® AV138, due to the combined effect of the highest peak stresses and reduced GIC and GIIC, while the other adhesives showed an improved behaviour by enabling a wide damage spread at Pm. Despite these facts, the experimental Pm results showed that the Araldite® AV138 achieves the highest Pm for all α between adhesives because, under the conditions of small stress gradients, the strengths of the adhesive are prevalent over the energy parameters. The numerical strength predictions were accurate in comparison with the experimental data, for all CZM law shapes and coupling modes. For the particular geometry tested in this work, the differences between CZM shapes were minimal. Thus, no significant errors are made in the choice of a less adequate law. However, it should be noted that this only occurs due to the particular load transfer characteristics of scarf joints. For other geometries, namely with higher stress gradients along the adhesive, non-negligible differences can be found between law shapes.

Abbreviations

- 2D:

-

two-dimensional

- a :

-

crack length

- a 0 :

-

initial crack length

- B :

-

width

- CZM:

-

cohesive zone models

- DCB:

-

double-Cantilever Beam

- d n :

-

damage variable in tension

- d s :

-

damage variable in shear

- E :

-

Young’s modulus

- ENF:

-

End-Notched Flexure

- E x :

-

Young’s modulus of the adherends

- FEM:

-

finite element method

- G :

-

shear modulus

- G I :

-

tensile strain energy release rate

- G IC :

-

critical tensile strain energy release rate

- G II :

-

shear strain energy release rate

- G IIC :

-

critical shear strain energy release rate

- L :

-

length (for the DCB specimen) or mid-span (for the ENF test)

- L O :

-

overlap length

- L S :

-

scarf length

- L T :

-

length

- MMB:

-

mixed-mode bending

- P :

-

load

- P m :

-

maximum load

- P u :

-

load per unit width applied at the specimen ends

- SDEG:

-

damage variable

- t A :

-

adhesive thickness

- t n :

-

cohesive stress in tension

- t 0n :

-

cohesive strength in tension

- t undn :

-

current value of tn without stiffness loss

- t P :

-

adherends’ thickness

- t s :

-

cohesive stress in shear

- t 0s :

-

cohesive strength in shear

- t unds :

-

current value of ts without stiffness loss

- x :

-

coordinate tangential to the adhesive layer

- XFEM:

-

extended finite element method

- Δ:

-

percentile difference between Pm for each independent model and the mixed-mode triangular model

- α :

-

scarf angle

- α exp :

-

parameter to specify the softening evolution

- δ :

-

displacement

- δ n :

-

relative displacement in tension

- δ 0n :

-

relative displacement at t 0n

- δ fn :

-

tensile relative displacement at failure

- δ sn :

-

tensile stress softening onset displacement of the trapezoidal CZM law

- δ s :

-

relative displacement in shear

- δ 0s :

-

relative displacement at t 0s

- δ fs :

-

shear relative displacement at failure

- δ ss :

-

shear stress softening onset displacement of the trapezoidal CZM law

- ε :

-

strain

- ε n :

-

tensile strain

- ε s :

-

shear strain

- θ o :

-

relative rotation of the adherends at the crack tip

- θ p :

-

relative rotation of the adherends measured at the loading line

- σ :

-

peel stresses

- σ :

-

stress

- σ f :

-

tensile strength

- τ :

-

shear stresses

- τ avg :

-

average shear stress in the adhesive layer

- τ f :

-

shear strength

References

Petrie EM. Handbook of adhesives and sealants. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2000.

Li J, Yan Y, Zhang T, Liang Z. Experimental study of adhesively bonded CFRP joints subjected to tensile loads. In J Adhes Adhes. 2015;57:95–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijadhadh.2014.11.001.

Grant LDR, Adams RD, da Silva LFM. Experimental and numerical analysis of single-lap joints for the automotive industry. Int J Adhes Adhes. 2009;29(4):405–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijadhadh.2008.09.001.

Llopart PL, Tserpes KI, Labeas GN. Experimental and numerical investigation of the influence of imperfect bonding on the strength of NCF double-lap shear joints. Compos Struct. 2010;92(7):1673–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruct.2009.12.001.

Gleich DM, Van Tooren MJL, De Haan PAJ. Shear and peel stress analysis of an adhesively bonded scarf joint. J Adhes Sci Technol. 2000;14(6):879–93. https://doi.org/10.1163/156856100742942.

Moreira RDF, Campilho RDSG. Strength improvement of adhesively-bonded scarf repairs in aluminium structures with external reinforcements. Eng Struct. 2015;101:99–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engstruct.2015.07.001.

Moreira RDF, Campilho RDSG. Parametric study of the reinforcement geometry on tensile loaded scarf adhesive repairs. J Adhes. 2016;92(7–9):586–609. https://doi.org/10.1080/00218464.2015.1095639.

Volkersen O. Die nietkraftoerteilung in zubeanspruchten nietverbindungen konstanten loschonquerschnitten. Luftfahrtforschung. 1938;15:41–7.

Goland M, Reissner E. The stresses in cemented joints. J Appl Mech. 1944;66:A17–27.

Penado FE. A simplified method for the geometrically nonlinear analysis of the single lap joint. J Thermoplast Compos. 1998;11(3):272–87. https://doi.org/10.1177/089270579801100306.

Li WD, Ma M, Han X, Tang LP, Zhao JN, Gao EP. Strength prediction of adhesively bonded single lap joints under salt spray environment using a cohesive zone model. J Adhes. 2016;92(11):916–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/00218464.2015.1058164.

Kafkalidis MS, Thouless MD. The effects of geometry and material properties on the fracture of single lap-shear joints. Int J Solids Struct. 2002;39(17):4367–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0020-7683(02)00344-X.

Mubashar A, Ashcroft IA, Crocombe AD. Modelling damage and failure in adhesive joints using a combined XFEM-cohesive element methodology. J Adhes. 2014;90(8):682–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/00218464.2013.826580.

Pascoe JA, Alderliesten RC, Benedictus R. Methods for the prediction of fatigue delamination growth in composites and adhesive bonds—a critical review. Eng Fract Mech. 2013;112–113:72–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfracmech.2013.10.003.

Anyfantis KN, Tsouvalis NG. A novel traction–separation law for the prediction of the mixed mode response of ductile adhesive joints. Int J Solids Struct. 2012;49(1):213–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsolstr.2011.10.001.

Turon A, Dávila CG, Camanho PP, Costa J. An engineering solution for mesh size effects in the simulation of delamination using cohesive zone models. Eng Fract Mech. 2007;74(10):1665–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfracmech.2006.08.025.

Rocha RJB, Campilho RDSG. Evaluation of different modelling conditions in the cohesive zone analysis of single-lap bonded joints. J Adhes. 2018;94(7):562–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/00218464.2017.1307107.

Azevedo JCS, Campilho RDSG, da Silva FJG, Faneco TMS, Lopes RM. Cohesive law estimation of adhesive joints in mode II condition. Theor Appl Fract Mech. 2015;80:143–54.

Andersson T, Stigh U. The stress–elongation relation for an adhesive layer loaded in peel using equilibrium of energetic forces. Int J Solids Struct. 2004;41(2):413–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsolstr.2003.09.039.

Ji G, Ouyang Z, Li G, Ibekwe S, Pang S-S. Effects of adhesive thickness on global and local Mode-I interfacial fracture of bonded joints. Int J Solids Struct. 2010;47(18–19):2445–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsolstr.2010.05.006.

Leffler K, Alfredsson KS, Stigh U. Shear behaviour of adhesive layers. Int J Solids Struct. 2007;44(2):530–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsolstr.2006.04.036.

Jumel J, Ben Salem N, Budzik MK, Shanahan MER. Measurement of interface cohesive stresses and strains evolutions with combined mixed mode crack propagation test and backface strain monitoring measurements. Int J Solids Struct. 2015;52:33–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsolstr.2014.09.004.

Gheibi MR, Shojaeefard MH, Saeidi Googarchin H. Direct determination of a new mode-dependent cohesive zone model to simulate metal-to-metal adhesive joints. J Adhes. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1080/00218464.2018.1455145.

Carvalho UTF, Campilho RDSG. Validation of pure tensile and shear cohesive laws obtained by the direct method with single-lap joints. Int J Adhes Adhes. 2017;77(Supplement C):41–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijadhadh.2017.04.002.

Campilho RDSG, Banea MD, Pinto AMG, da Silva LFM, de Jesus AMP. Strength prediction of single- and double-lap joints by standard and extended finite element modelling. Int J Adhes Adhes. 2011;31(5):363–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijadhadh.2010.09.008.

Neto JABP, Campilho RDSG, da Silva LFM. Parametric study of adhesive joints with composites. Int J Adhes Adhes. 2012;37:96–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijadhadh.2012.01.019.

Campilho RDSG, Banea MD, Neto JABP, da Silva LFM. Modelling adhesive joints with cohesive zone models: effect of the cohesive law shape of the adhesive layer. Int J Adhes Adhes. 2013;44:48–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijadhadh.2013.02.006.

Faneco T, Campilho R, Silva F, Lopes R. Strength and fracture characterization of a novel polyurethane adhesive for the automotive industry. J Test Eval. 2017;45(2):398–407. https://doi.org/10.1520/JTE20150335.

Wang H, Hao X, Yan K, Zhou H, Hua L. Ultrasonic vibration-strengthened adhesive bonding of CFRP-to-aluminum joints. J Mater Process Technol. 2018;257:213–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2018.03.003.

Rice JR. A path independent integral and the approximate analysis of strain concentration by notches and cracks. J Appl Mech. 1968;35(2):379–86. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.3601206.

Constante CJ, Campilho RDSG, Moura DC. Tensile fracture characterization of adhesive joints by standard and optical techniques. Eng Fract Mech. 2015;136:292–304. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfracmech.2015.02.010.

Leitão ACC, Campilho RDSG, Moura DC. Shear characterization of adhesive layers by advanced optical techniques. Exp Mech. 2016;56:493–506. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11340-015-0111-4.

Abaqus®. Documentation of the software Abaqus®. Vélizy-Villacoublay: Dassault Systèmes; 2013.

Tsai MY, Morton J. An investigation into the stresses in double-lap adhesive joints with laminated composite adherends. Int J Solids Struct. 2010;47(24):3317–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsolstr.2010.08.011.

Liao L, Huang C, Sawa T. Effect of adhesive thickness, adhesive type and scarf angle on the mechanical properties of scarf adhesive joints. Int J Solids Struct. 2013;50(25):4333–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsolstr.2013.09.005.

Campilho RDSG, Moura DC, Banea MD, da Silva LFM. Adhesive thickness effects of a ductile adhesive by optical measurement techniques. Int J Adhes Adhes. 2015;57:125–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijadhadh.2014.12.004.

Lee D-B, Ikeda T, Miyazaki N, Choi N-S. Effect of bond thickness on the fracture toughness of adhesive joints. J Eng Mater Tech. 2004;126(1):14–8. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.1631433.

Afendi M, Teramoto T, Bakri HB. Strength prediction of epoxy adhesively bonded scarf joints of dissimilar adherends. Int J Adhes Adhes. 2011;31(6):402–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijadhadh.2011.03.001.

Imanaka M, Fujinami A, Suzuki Y. Fracture and yield behavior of adhesively bonded joints under triaxial stress conditions. J Mater Sci. 2000;35(10):2481–91. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1004769719895.

Imanaka M, Suzuki Y. Yield behavior of rubber-modified epoxy adhesives under multiaxial stress conditions. J Adhes Sci Technol. 2002;16(12):1687–700. https://doi.org/10.1163/15685610260255288.

Objois A, Fargette B, Gilibert Y. The influence of the bevel angle on the micro-mechanical behaviour of bonded scarf joints. J Adhes Sci Technol. 2000;14(8):1057–70. https://doi.org/10.1163/156856100743077.

Objois A, Assih J, Troalen JP. Theoretical method to predict the first microcracks in a scarf joint. J Adhesion. 2005;81(9):893–909. https://doi.org/10.1080/00218460500222819.

Odi RA, Friend CM. An improved 2D model for bonded composite joints. Int J Adhes Adhes. 2004;24(5):389–405. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijadhadh.2001.06.001.

Wang CH, Gunnion AJ. On the design methodology of scarf repairs to composite laminates. Compos Sci Technol. 2008;68(1):35–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compscitech.2007.05.045.

Adams RD, Mallick V. The effect of temperature on the strength of adhesively-bonded composite-aluminium joints. J Adhes. 1993;43(1–2):17–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/00218469308026585.

Davis M, Bond D. Principles and practices of adhesive bonded structural joints and repairs. Int J Adhes Adhes. 1999;19(2–3):91–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0143-7496(98)00026-8.

Alves DL, Campilho RDSG, Moreira RDF, Silva FJG, da Silva LFM. Experimental and numerical analysis of hybrid adhesively-bonded scarf joints. Int J Adhes Adhes. 2018;83:87–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijadhadh.2018.05.011.

Yang Q, Cox B. Cohesive models for damage evolution in laminated composites. Int J Fract. 2005;133(2):107–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10704-005-4729-6.

Authors’ contributions

DFOS performed the experimental tests and respective data analysis, and he also performed the numerical analysis. RDSGC and UTFC developed the numerical technique and participated the paper writing. FJGdaS participated in the paper writing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Sika® Portugal for supplying the adhesive.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Funding

No funding was received.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Silva, D.F.O., Campilho, R.D.S.G., Silva, F.J.G. et al. Application a direct/cohesive zone method for the evaluation of scarf adhesive joints. Appl Adhes Sci 6, 13 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40563-018-0115-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40563-018-0115-2