Abstract

Background

Cellular patterns in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) are used to distinguish or rule out particular diseases in patients with acute respiratory failure (ARF). However, whether BALF cellular patterns can predict mortality or not is unknown. We test the hypothesis that BALF cellular patterns have predictive value for mortality in patients with ARF.

Methods

This was a retrospective single-center observational study conducted in a Japanese University Hospital. Consecutive patients (n = 78) with both pulmonary infiltrates and ARF who were examined by bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) between April 2015 and May 2018 with at least 1 year of follow-up were analyzed. Primary analysis was receiver operating characteristic curve—area under the curve (ROC-AUC) analysis for 1-year mortality.

Results

Among the final sample size of 78 patients, survivors (n = 56) had significantly increased lymphocyte and eosinophil counts and decreased neutrophil counts in BALF compared with non-survivors (n = 22). Among the fractions, lymphocyte count was the most significantly different (30 [12-50] vs. 7.0 [2.9-13]%, P <0.0001). In the ROC curve analysis of the association of BALF lymphocytes with 1-year mortality, the AUC was 0.787 (P <0.0001, cut-off value [Youden index] 19.0%). Furthermore, ≥20% BALF lymphocytes were significantly associated with increased survival with adjustment for baseline imbalances (1-year adjusted hazard ratio, 0.0929; 95% confidence interval, 0.0147–0.323, P <0.0001; 90-day P =0.0012). Increased survival was significantly associated with ≥20% BALF lymphocytes in both interstitial lung disease (ILD) and non-ILD subgroups (P =0.0052 and P =0.0033, respectively). In secondary outcome analysis, patients with ≥20% BALF lymphocytes had significantly increased ventilator-free days, which represents less respiratory dysfunction than those with <20% BALF lymphocytes.

Conclusions

In the patients with ARF, ≥20% lymphocytes in BALF was associated with significantly less ventilatory support, lower mortality at both 90-day and 1-year follow-ups.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Acute respiratory failure (ARF) is a common and life-threatening medical condition that is conventionally defined by an arterial oxygen tension of <60 mmHg or as a triad of clinical signs, radiographic findings, and gas exchange alternations [1]. Nearly 2 million people are hospitalized with ARF annually in the USA, and the mortality of ARF remains over 20% [2]. Etiologies of ARF include pneumonia, interstitial lung disease (ILD), acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), malignant tumors, and congestive heart failure. The broad spectrum of the etiologies requires comprehensive diagnostic investigation. Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid (BALF) using fiber-optic bronchoscopy can help diagnose a wide variety of lung diseases [3,4,5]. Following diagnosis, prediction of clinical outcomes of ARF is key for clinical management since this prediction may contribute to the improvement of clinical outcomes.

Substantial studies have revealed the diagnostic value of BALF cellular patterns in patients with lung diseases, including acute and chronic bilateral infiltrative lung disease [6, 7]. However, investigation of the value of BALF cellular patterns for prediction of mortality remains insufficient. Previous studies have investigated the prognostic value of BALF cellular patterns in patients with chronic respiratory failure, including those with hypersensitivity pneumonitis (HP) [8] and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) [9,10,11]; however, investigation of the prognostic value of BALF cellular patterns in patients with ARF is sparse.

Herein, we test the hypothesis that BALF cellular patterns have prognostic value in patients with ARF. The primary measure was 1-year mortality as a long-term outcome. Short-term (90-day) mortality and ventilator-free days were analyzed as secondary outcomes.

Methods

Ethical approval

All study procedures involving human participants were approved by the Human Ethics Committee of the Graduate School of Medicine, Chiba University (no. 2584). This study was designed and conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and subsequent amendments. The requirement for informed consent was waived by the ethics committee because this retrospective analysis was limited to preexisting data collected as standard-of-care by respiratory physicians. Data anonymization was used, and privacy issues were protected. Approval for the opt-out consent method was given by the Chiba University Hospital.

Study design and definition

This single-center retrospective study included consecutive patients who had ARF and underwent BAL between April 2015 and May 2018 at Chiba University Hospital, Japan. ARF was defined by the following criteria: worsening or development of dyspnea manifested within 30 days, newly emerging bilateral ground glass opacities, and/or the consolidation on chest computed tomography scan, PaO2/FiO2 ratio of less than 300 mmHg in patients with or without oxygen therapy or non-invasive ventilation (NIV), or, regardless of the PaO2/FiO2 ratio, patients with mechanical ventilation. Patients with hypoxia caused by heart failure, fluid overload, or pulmonary thromboembolism were excluded.

The etiologies of ARF, including infection, collagen vascular disease, malignancy, or others, were categorized as ILD or non-ILD. ILD included organizing pneumonia (OP), HP, eosinophilic pneumonia, IPF, acute interstitial pneumonia, drug-induced lung injury, and non-specific interstitial pneumonia. HP was diagnosed based on the American Thoracic Society (ATS)/Japanese Respiratory Society (JRS)/Asociación Latinoamericana de Tórax HP clinical practice guideline of 2020 [12]. IPF was diagnosed based on the ATS/European Respiratory Society/JRS/Latin American Thoracic Association IPF guidelines of 2018 [13]. Etiologies were diagnosed based on microbiological evaluations, BALF cellular patterns, and radiographic and pathologic findings by experienced respiratory physicians.

BAL procedure and BALF analysis

Experienced respiratory physicians performed BAL using a fiber-optic bronchoscope in compliance with ATS guidelines [6] and the institutional criteria. A total of 150 mL of sterile saline solution were divided into three 50-mL aliquots and instilled into the most affected lobe. After instillation of each aliquot, the solution was gently recovered, and the BALF was filtered through sterile gauze and centrifuged to remove mucus and cells. The total cell number was counted manually using a hemocytometer. Differential cell counts were conducted after centrifugation (1 min, 1500 rpm) and Wright–Giemsa staining.

Statistical analysis

The primary outcome was 1-year mortality. The primary analysis included the generation of an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC-AUC) to evaluate the prognostic value of BALF for 1-year mortality. The optimal cut-off value was calculated using the Youden index. The secondary analysis included a Cox regression to test significant effects on hazard of death over 1-year. We chose this approach to adjust for baseline imbalances in variables, including PaO2/FiO2 ratio and ILD, based on previous reports [14]. The Cox regression analysis was repeated in ILD and non-ILD subgroups. The secondary outcome variables were 90-day mortality and days alive and free of ventilator out of 28 days (VFD). Data are expressed as median and interquartile range. Baseline characteristics were analyzed using Fisher’s exact test or Mann–Whitney U test. Two-tailed p values <0.05 were considered as significant. All analyses were performed using JMP pro 13.2.0 (SAS Institute Inc. Cary, NC, USA).

Results

There were 830 patients who underwent BAL during the study period. Of these, 78 who had ARF were analyzed (Fig. 1). At baseline (Table 1), non-survivors had a significantly lower prevalence of ILD and a significantly higher prevalence of requirement for NIV or mechanical ventilation at the time of BAL compared to survivors. Lymphocyte and eosinophil counts were significantly decreased, and neutrophil counts were significantly increased in the BALF of non-survivors compared to that of survivors (Table 1).

In the primary analysis of the prognostic value of BALF for 1-year mortality using AUC analysis, lymphocytes had the highest prognostic value among four fractions (AUC, 0.787; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.657–0.878; P <0.0001). The cut-off value for the lymphocyte fraction in predicting 1-year mortality was 19.0% (sensitivity, 0.909; specificity, 0.643) (Table 2, Fig. 2). With respect to the Youden index findings, we defined 20% as the cut-off value for lymphocytes in BALF in 1-year mortality (sensitivity, 0.909; specificity, 0.607) for clinical implication.

In the secondary analysis using Cox regression, we categorized the patients into those with ≥20% BALF lymphocytes and those with <20% BALF lymphocytes based on significant findings from the primary analysis. The number of survivors and non-survivors with ≥20% lymphocytes in BALF at 1 year was 35 and 2, respectively. The number of those with <20% lymphocytes in BALF at 1 year was 21 and 20, respectively. Survival rates at 1 year were 94.6% in ≥20% BALF lymphocytes and 51.2% in <20% BALF lymphocytes, respectively (Fig. 3a). Patients with ≥20% BALF lymphocytes had significantly decreased mortality after adjusting for baseline imbalances (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.0929; 95% CI, 0.0147–0.323; P <0.0001) (Table 3). Repeat analysis of 90-day mortality yielded the same conclusion (Table 3). Subgroup analysis of ILD and non-ILD groups also revealed significantly decreased mortality in the ≥20% BALF lymphocyte subgroup. In ILD, survival rates were 100% in ≥20% BALF lymphocytes and 66.7% in <20% BALF lymphocytes, respectively (Fig. 3b). In non-ILD, survival rates at 1 year were 88.2% in ≥20% BALF lymphocytes and 39.1% in <20% BALF lymphocytes, respectively (Fig. 3c).

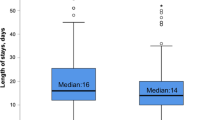

Next, we analyzed the association between ≥20% BALF lymphocytes and VFD. A BALF lymphocyte fraction of ≥20% was significantly associated with increased VFD compared to <20% BALF lymphocytes (13 [1-28] vs. 28 [28-28] days, P <0.0001), which indicates that an increased BALF lymphocyte fraction is associated with better respiratory outcomes.

Discussion

In the study of BALF in patients with ARF, the BALF lymphocyte fraction had significant prognostic value. Patients with ≥20% BALF lymphocytes had significantly increased survival at both the 90-day and 1-year observational time points and significantly less ventilator support during the 28-day period.

To our knowledge, the prognostic value of BALF lymphocytes in survival has not been documented in ARF. A key finding of the present study is that BALF lymphocytes had high prognostic value for predicting 1-year mortality in ARF patients (AUC, 0.787; cut-off value, 19.0%). Specifically, patients with ≥20% BALF lymphocytes had significantly decreased 1-year mortality compared to patients with <20% BALF lymphocytes. In line with this finding, a previous investigation of acute exacerbations of chronic progressive interstitial pneumonia with a small sample size (n = 37) showed that patients with ≥15% BALF lymphocytes had significantly decreased mortality compared to patients with <15% BALF lymphocytes [14]. Since repeat analysis of 90-day mortality revealed the same results, we concluded that BALF lymphocytes have high prognostic value and that ≥20% BALF lymphocytes are a potential threshold in ARF.

A BALF lymphocyte fraction of >15% represents a lymphocytic cellular pattern in ILD including OP, drug-induced pneumonitis, HP, and non-specific interstitial pneumonia [6]. Indeed, a previous report defined OP and drug-induced pneumonitis that were identified using open-lung biopsy as corticosteroid-sensitive pathologies in non-resolving ARDS [15]. These corticosteroid-sensitive pathologies were associated with better outcome. OP is one of the most common pathologies in ILD and is caused by idiopathic etiologies or is secondary to an inflammatory reaction to drugs, infection, collagen vascular disease, malignancy, or radiation therapy.

The mechanism of increasing lymphocytes in BALF remains unclear; however, natural killer and natural killer T-like cells, which are unique subgroups of lymphocytes, are increased in BALF of OP patients and may play important roles in disease [16]. They also mainly mediate innate anti-tumor and anti-viral immune responses and respond to a variety of cytokines [17]. Therefore, we speculated that some immune responses to tumor, infectious pathogens, and autoantibodies may also affect disease behavior such as secondary OP and improve survival rate for corticosteroid sensitivity in both ILD and non-ILD patients with ARF.

The present analysis of ventilator-free days revealed that patients with ≥20% BALF lymphocytes had less ventilatory support. VFD is a standard indicator of respiratory failure including that in patients with ARDS [18,19,20]. Indeed, improvement of respiratory physiology and shortened ventilator duration is clinically and economically meaningful [21]. Therefore, our findings strengthen primary analysis showing that mortality is linked to respiratory dysfunction.

Finally, it should be noted that our study was limited by being conducted retrospectively. Some patients with ILD were diagnosed without pathological findings because it was difficult to perform surgical lung biopsy in critically ill patients. In most patients who were excluded, recovering an adequate amount of BALF for analysis was challenging because their respiratory condition was unstable. Further large-scale studies must be conducted to confirm the findings of the current study.

Conclusions

In conclusion, BALF lymphocytes had significant prognostic value for 1-year survival in patients with ARF. Patients with ≥20% BALF lymphocytes had less ventilator support and significantly higher 1-year survival.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ARDS:

-

Acute respiratory distress syndrome

- ARF:

-

Acute respiratory failure

- ATS:

-

American thoracic society

- AUC:

-

Area under the receiver operating characteristic curve

- BAL:

-

Bronchoalveolar lavage

- BALF:

-

Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid

- HP:

-

Hypersensitivity pneumonitis

- ILD:

-

Interstitial lung disease

- IPF:

-

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

- JRS:

-

Japanese respiratory society

- NIV:

-

Non-invasive ventilation

- OP:

-

Organizing pneumonia

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristic

- ROC-AUC:

-

Receiver operating characteristic curve—area under the curve

- VFD:

-

Days alive and free of ventilator out of 28 days

References

Azoulay E, Mokart D, Kouatchet A, Demoule A, Lemiale V. Acute respiratory failure in immunocompromised adults. Lancet Respir Med. 2019;7:173–86.

Stefan MS, Shieh MS, Pekow PS, Rothberg MB, Steingrub JS, Lagu T, et al. Epidemiology and outcomes of acute respiratory failure in the United States, 2001-2009: a national survey. J Hosp Med. 2013;8:76–82.

Du Rand IA, Blaikley J, Booton R, Chaudhuri N, Gupta V, Khalid S, et al. British Thoracic Society guideline for diagnostic flexible bronchoscopy in adults: accredited by NICE. Thorax. 2013;68(Suppl 1):i1–i44.

Goldstein RA, Rohatgi PK, Bergofsky EH, Block ER, Daniele RP, Dantzker DR, et al. Clinical role of bronchoalveolar lavage in adults with pulmonary disease. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1990;142:481–6.

Kyo M, Hosokawa K, Ohshimo S, Kida Y, Tanabe Y, Shime N. Prognosis of pathogen-proven acute respiratory distress syndrome diagnosed from a protocol that includes bronchoalveolar lavage: a retrospective observational study. J Intensive Care. 2020;8:54.

Meyer KC, Raghu G, Baughman RP, Brown KK, Costabel U, du Bois RM, et al. An official American Thoracic Society clinical practice guideline: the clinical utility of bronchoalveolar lavage cellular analysis in interstitial lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:1004–14.

Choi SH, Hong SB, Hong HL, Kim SH, Huh JW, Sung H, et al. Usefulness of cellular analysis of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid for predicting the etiology of pneumonia in critically ill patients. Plos One. 2014;9:e97346.

Drent M, van Velzen-Blad H, Diamant M, Wagenaar SS, Hoogsteden HC, van den Bosch JM. Bronchoalveolar lavage in extrinsic allergic alveolitis: effect of time elapsed since antigen exposure. Eur Respir J. 1993;6:1276–81.

Lynch JP 3rd, Standiford TJ, Rolfe MW, Kunkel SL, Strieter RM. Neutrophilic alveolitis in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. The role of interleukin-8. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992;145:1433–9.

Haslam PL, Dewar A, Butchers P, Primett ZS, Newman-Taylor A, Turner-Warwick M. Mast cells, atypical lymphocytes, and neutrophils in bronchoalveolar lavage in extrinsic allergic alveolitis. Comparison with other interstitial lung diseases. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1987;135:35–47.

Kinder BW, Brown KK, Schwarz MI, Ix JH, Kervitsky A, King TE Jr. Baseline BAL neutrophilia predicts early mortality in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chest. 2008;133:226–32.

Raghu G, Remy-Jardin M, Ryerson CJ, Myers JL, Kreuter M, Vasakova M, et al. Diagnosis of hypersensitivity pneumonitis in adults. An official ATS/JRS/ALAT clinical practice guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202:e36–69.

Raghu G, Remy-Jardin M, Myers JL, Richeldi L, Ryerson CJ, Lederer DJ, et al. Diagnosis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT clinical practice guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;198:e44–68.

Takei R, Arita M, Kumagai S, Ito Y, Noyama M, Tokioka F, et al. Impact of lymphocyte differential count > 15% in BALF on the mortality of patients with acute exacerbation of chronic fibrosing idiopathic interstitial pneumonia. BMC Pulm Med. 2017;17:67.

Gerard L, Bidoul T, Castanares-Zapatero D, Wittebole X, Lacroix V, Froidure A, et al. Open lung biopsy in nonresolving acute respiratory distress syndrome commonly identifies corticosteroid-sensitive pathologies, associated with better outcome. Crit Care Med. 2018;46:907–14.

Papakosta D, Manika K, Gounari E, Kyriazis G, Kontakiotis T, Spyropoulos G, et al. Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid and blood natural killer and natural killer T-like cells in cryptogenic organizing pneumonia. Respirology. 2014;19:748–54.

Traba J, Waldmann TA, Anton OM. Analysis of human natural killer cell metabolism. J Vis Exp. 2020;160.

Rice TW, Wheeler AP, Thompson BT, DeBoisblanc BP, Steingrub J, Rock P, NIH NHLBI Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network of Investigators. Enteral omega-3 fatty acid, gamma-linolenic acid, and antioxidant supplementation in acute lung injury. JAMA. 2011;306:1574–8.

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) Clinical Trials Network, Rice TW, Wheeler AP, Thompson BT, Steingrub J, Hite RD, et al. Initial trophic vs full enteral feeding in patients with acute lung injury: the Eden randomized trial. JAMA. 2012;307:795–80.

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) Clinical Trials Network, Matthay MA, Brower RG, Carson S, Douglas IS, Eisner M, et al. Randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial of an aerosolized β2-agonist for treatment of acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184:561–8.

Yehya N, Harhay MO, Curley MAQ, Schoenfeld DA, Reeder RW. Reappraisal of ventilator-free days in critical care research. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;200:828–36.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Enago (www.enago.jp) for the English language review.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YH, MA, JT, KY, and KTa contributed to the study concept and design. YI, MS, KS, TK, and KTs contributed to the data curation and investigation of the patients. YH and MA examined the enrolled patients in the hospital. YH, TS, and TN performed the statistical analyses. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All study procedures involving human participants were approved by the Human Ethics Committee of the Graduate School of Medicine, Chiba University (no. 2584).

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Hirasawa, Y., Nakada, Ta., Shimazui, T. et al. Prognostic value of lymphocyte counts in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid in patients with acute respiratory failure: a retrospective cohort study. j intensive care 9, 21 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40560-021-00536-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40560-021-00536-w