Abstract

Background

Persistent declines in migratory songbird populations continue to motivate research exploring contributing factors to inform conservation efforts. Nearctic-Neotropical migratory species’ population declines have been linked to habitat loss and reductions in habitat quality due to increasing urbanization in areas used throughout the annual cycle. Despite an increase in the number of studies on post-fledging ecology, generally characterized by the period between fledging and dispersal from natal areas or migration, contextual research linking post-fledging survival and habitat use to anthropogenic factors remains limited.

Methods

Here, we examined habitat use of post-fledging habitat-generalist gray catbirds (Dumetella caroliniensis), and habitat-specialist wood thrushes (Hylocichla mustelina), up to 88 days after fledging within an urbanized landscape. These Neotropical migratory species share many life-history traits, exhibit differential degrees of habitat specialization, and co-occur in urbanized landscapes. Starting from daily movement data, we used time-integrated Brownian bridges to generate probability density functions of each species’ probability of occurrence, and home range among 16 land cover classes including roads from the US Geological Survey National Land Cover Database for each species.

Results

Habitat use differed between pre- and post-independence periods. After controlling for factors that influence habitat use (i.e., pre- or post-independence period, fate (whether individuals survived or not), and land cover class), we found that wood thrushes occupied home ranges containing six times more forest land cover than catbirds. In contrast, catbirds occupied home ranges containing twice the area of roads compared to wood thrushes. Wood thrushes had greater variance for area used (km2) among land cover classes within home ranges compared to catbirds. However, once fledglings achieved independence from parents, wood thrushes had lower variance associated with area used compared to catbirds.

Conclusions

Our findings support predictions that habitat-generalist gray catbirds spend more time in developed areas, less time in forest habitat, and use areas with more roads than the forest-specialist wood thrush. We found strong effects of pre- and post-independence periods on all of the response variables we tested. Species-specific habitat use patterns will likely be affected by projected increases in urbanization over the next several decades leading to further reductions in available forest habitat and increased road density, and will have important implications for the ecology and conservation of these birds.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Organismal movement, habitat use, and interactions with the underlying resources therein, continue to be of particular importance in ecology and conservation [1,2,3,4]. Through studying the dynamics of animal movement, we can elucidate important responses to environmental change, especially anthropogenic stressors which can directly influence food availability [5, 6], breeding habitat [7, 8], and cover [9, 10]. Hence, habitat use patterns can be shaped by non-mutually exclusive resource selection interactions and trade-offs in relation to changes in resource availability [11, 12].

Movement data have been used successfully to analyze space and resource use patterns in birds during breeding [13, 14], and specifically, in response to anthropogenic factors [15, 16]. These studies have led to important insights into determining migration routes and migratory connectivity [17,18,19] which are helping to identify population-limiting factors [20], and improve conservation efforts throughout the annual cycle [21, 22]. Additionally, studies on fledgling movements and habitat use provide key insights into this particularly vulnerable life-stage [23,24,25,26].

While more studies are now being conducted to help fill information gaps throughout the annual cycle during migratory [27,28,29,30], and over-wintering periods [31,32,33], there still remain important gaps. One of these critical gaps is related to the post-fledging period [34], which we define for this study as the period after nestlings leave the nest up until departure on fall-migratory flights. Collectively, these research efforts provide more detailed information on how species respond to anthropogenic effects, like urbanization, as well as providing species-specific information which can improve our ability to promote conservation efforts for species like the wood thrush (Hylocichla mustelina), which is a forest habitat specialist and Partners in Flight species of continental conservation concern [35].

Given the increasing rate of anthropogenic change and its linkages with observed widespread reductions in habitat availability, quality, and conincident declines in bird populations [36], more research is warranted to help better understand and predict how birds will respond to future urbanized ecosystems. For example, in a recent review and meta-analysis, [37] demonstrated how habitat fragmentation per se, is not only not necessarily negatively correlated with species or community-level responses, but instead may, generally have a positive influence on populations or biological diversity. These findings indicate that complexity associated with land cover changes (beyond simple metrics of fragmentation when accounting for total area of available habitat), must be considered when attempting to tease apart the patterns and processes associated with anthropogenic effects on habitat use, survival, and population trends of species. Indeed, this is being addressed by a growing body of research on bird responses to urbanization [38,39,40,41]. However, we must continue to investigate avian responses to urbanization during critical periods in the annual cycle that remain under-studied [34]. Of particular importance is the post-fledging period, during which birds have high mortality rates in general [42,43,44,45,46].

To better improve our understanding of how anthropogenic effects of urbanization can influence habitat use during the post-fledging period, we conducted a comparative study using telemetry-based movement data of individual juvenile wood thrushes and gray catbirds (Dumetella carolinensis; hereafter catbird) during the post-fledging period. Although these two species are closely-related phylogenetically [47] and share similar life-history traits [48, 49], they exhibit differential responses to urbanization, in part resulting from their habitat-generalist or –specialist behavior, and currently have opposing annual population trend estimates (catbird: 0.42%, and wood thrush: − 2.77%; [50]. Differing habitat use patterns can then lead to different levels of exposure to examples of potential negative effects from urbanization on birds that include increased risk of mortality due to collisions with buildings or cars [51,52,53], predation by domestic cats [54,55,56], pollution [57, 58], and reductions in availability of food and habitat [7, 59,60,61].

Our objectives were to estimate 1) post-fledging home ranges, and 2) movement metrics of catbirds and wood thrushes during both pre- and post-independence periods, which we define here as ≤ 20 days and > 20 days from leaving the nest [48, 49]. To measure the response of post-fledging habitat use within an urbanized landscape, we examined patterns of habitat use within wood thrush and catbird home ranges during pre- and post-independence periods, and explored their respective use, particularly in relation to forested and roaded habitats. Loss and degradation of high-quality forest habitat, along with increased density of roads are directly related to urbanization and the increasing spread of developed land cover, which can pose myriad threats to wildlife [62, 63], and birds in particular [64, 65]. Through continued study, we can help better understand how species respond (e.g., behavioral aspects of habitat and resource use) within urbanized landscapes. This information is valuable for conserving both urban-tolerant species and urban-avoiding species.

Methods

Study area

Our study area in and around Newark, Delaware (39.6837° N, 75.7497° W) and Landenberg, Pennsylvania (39.7778° N, 75.7716° W) is located in the human-dominated eastern mid-Atlantic United States. We tracked catbird and wood thrush fledgling movement using very high frequency (VHF) radio transmitters fitted on individuals that originated from 69 nests within 13 discrete forest fragments in a generally, urbanized landscape [66]. We sampled sites within forest fragments that ranged in area from 5 to 163 ha, and consisted of dominant canopy tree species including Fagus grandifolia, Acer rubrum, Quercus spp., Liriodendron tulipifera, and Liquidambar styraciflua. Additionally, sites characteristically supported both native and non-native understory woody species including Lindera benzoin, Viburnum spp., Clethra alnifolia, Rosa multiflora, Eleagnus umbellata, and Rubus spp.

Data collection

During the 2012–2014 breeding seasons (i.e., May–August), we systematically searched 23 forest fragments; 13 of which contained nests of wood thrushes and catbirds. We visually monitored nests every 3–4 days [67]. We banded (with aluminum US Geological Survey bands; Permit number: 23475), and fitted VHF radio-tags to nestling catbirds and wood thrushes 1–3 days prior to fledging [48, 49]. We randomly selected 1 or 2 nestlings from each nest and attached VHF radio-transmitters (weighing < 1 g) ranging in frequencies between 150 and 151 MHz (Blackburn transmitters, Nacogdoches, Texas, USA). We extracted nestlings by hand from nests, attached transmitters using a 1 mm elastic thread fitted with a figure-8 loop harness [68], and then returned nestlings to their nests.

Using hand-held Yagi antennas attached to programmable receivers (Advanced Telemetry Systems, Isanti, Minnesota, USA), we located each individual once per day throughout the study period until they either died, the radio-transmitter battery failed, or they dispersed from the study area. When a bird was successfully located by homing in on individuals, we used global positioning system (GPS) units (± 3-m accuracy) to record location coordinates (latitude and longitude). We identified mortality events when transmitters were recovered containing part or all of a dead individual’s body, blood, or feathers. In some circumstances, where the locations of birds were unable to be determined if an individual was out of range compared to its previous location, we used a roof-mounted omnidirectional antenna on top of a vehicle to search an increasingly larger area beginning at the bird’s previous known location. These searches continued for all missing birds each day and lasted until the bird was located or up to 5 days beyond the estimated date of transmitter battery failure.

Determining habitat use

To determine the areas that individual birds used, we used a Brownian bridge movement model (BBMM), which is a time-integrated, path-based (as opposed to a point-based) approach to estimate space use. We preferred BBMMs due to recent comparisons among space use estimators suggesting that the incorporation of temporal components leads to more reliable results than traditional kernel-based estimators [69]. Brownian motion (i.e., a random motion of individuals conditioned by a start and end point), is referred to as a Brownian bridge (BB) and is used in the BBMM. In a BB, an individual’s position at any time instance is described by a normal distribution. In between two consecutive fixes, an infinite number of possible paths can be simulated and the (time-independent) marginal probability density function (PDF) at each location can be obtained by averaging these normal distributions over time. The PDF of this so-called time-integrated BB (hereafter referred to as home range) is used in animal movement research to delineate important areas. The latter is realized using the so-called BBMM which relies on the home ranges. More specifically, the BBMM involves the construction of the PDF of a weighted average of home ranges between every two consecutive fixes. The resulting PDF describes the probability density that an animal is positioned at a certain location at an arbitrary moment in time within the considered time interval. It is determined by the registered locations, the time between those locations and the animal’s mobility, which are not accounted for in some alternative approaches [70, 71]. Here, the PDF is constructed for each individual and for each period pre- and post-independence using the analytical solution proposed by [72] using Mathematica (ver. 11.1.1.0). Given that our study focuses on fledglings who are exploring their habitat, the assumption of a random walk in between two fixes seems justified.

From the resulting PDF, the home range can be defined by calculating a threshold so that the subset of pixels having a PDF value in their center that is greater than or equal to this threshold, represents 95% of the volume under the PDF. This subset represents the area with the highest possible PDF values where the individuals are expected to be located during 95% of the studied time interval [73]. Additionally, following censoring individuals that died 1 day after leaving the nest, we categorized the fate of individuals as either survived or died (see [66] for details) independently within pre- and post-independence periods.

We used Land Use/Land Cover data from the National Land Cover Database (NLCD; 30 × 30 m resolution; [74]) to quantify relative land cover composition with the areas used by birds during pre- and post-independence periods. These 2011 NLCD data included the following land cover/land use categories: Developed Open Space, Developed Low Intensity, Developed Medium Intensity, Developed High Intensity, Barren Land, Deciduous Forest, Evergreen Forest, Mixed Forest, Scrub/Shrub, Grassland/Herbaceous, Pasture/Hay, Cultivated Crops, Woody Wetlands, Emergent Herbaceous Wetlands, and Open Water [74]. We then embedded roads within the land cover raster using rasterized (30-m resolution) Topologically Integrated Geographic Encoding and Referencing (TIGER) data [75]; Fig. 1).

First, we extracted the total number of cells assigned to each land cover class (including roads as an additional class), and calculated the proportion of each land cover class within the home range for each individual during pre- and post-independent periods. We then weighted these proportions by the PDF value within each cell from within the area of the home range for each individual during pre- and post-independent periods. This resulted in the weighted relative proportion of each land cover class. To determine the respective area (km2) of each land cover class, we multiplied the weighted relative proportions (which all summed to 1) by the total area (km2) of the home range. We then calculated the mean and standard error for both the weighted relative proportions and area (km2) of each land cover class for both species during pre- and post-independence periods. Since none of the individual birds from our study used Grassland/Herbaceous, Emergent Herbaceous Wetland, Barren Land, or Open Water land cover classes, we removed these before performing statistical analyses.

To gain understanding into how underlying movement metrics were related to observed patterns in habitat use within and between species and between pre- and post-independence periods, we computed several movement data metrics. We calculated the mean home range size (km2), path length (m), total displacement (m), and net displacement (m). We defined home range size as the size of the 95% CI of the BB. We defined path length as the Euclidean distance between a unique pair of consecutive locations where an individual occurred. We defined total displacement as the sum of distance moved per individual, net displacement as the Euclidean distance between the first and final recorded locations for an individual. We calculated these metrics for each individual during pre- and post-independence periods, and then computed means and variance components.

Statistical analyses

We conducted a chi-square test to test whether mean relative proportions of land cover classes within home ranges were independent within and between species for both the pre- and post-independence periods. For this test, any land cover classes with counts < 2 were removed. To test null hypotheses that catbirds and wood thrushes responded similarly in their habitat use and movement behavior we used the R package ‘lme4’ [76] to fit generalized linear mixed-effects models. We tested for differences in response variables: land cover area (km2) within home ranges to the main effects of and interactions between predictor variables: 1) species, 2) land cover class, and 3) independence status. When significant differences were detected from mixed-effects models (a ≤ 0.05) for predictor variables with more than two factor-levels, we used the ‘multcomp’ package to implement Tukey’s HSD post hoc methods to test for pair-wise differences [77]. In addition, to assess differences within and between species, we compared the coefficient of variation (CV) of land cover area (km2) within and among species. Additionally, we computed the difference in CV of land cover area (km2) between pre- and post-independence periods by computing a value for delta CV (∆CV = CVpost-independence – CVpre-indpendence). We also fit generalized linear mixed-effects models for each of the following movement metric response variables (i.e., home range size, path length, total displacement, and net displacement) to the main effect and all interactions of the following predictors: species, fate, and independence status. To account for potential bias due to fledglings dying during the study period, originating from the same nest, and differences in sampling effort among years, we included fate (i.e., died or survived) as a fixed effect, and unique nest ID nested within Year as a random effect within models. To ascertain significant differences, we used parametric bootstrapping (PBtest) to test for differences between full and reduced models (i.e., to test for significant contributions of each independent covariate to variance explained) with the ‘pbkrtest’ package [78]. We tested all data for departures from normality using visual inspection of quantile-quantile residual plots of variables, and all statistical analyses were conducted using R ver. 3.4.3; [79].

Results

We analyzed location data for fledgling catbirds (n = 52) and wood thrushes (n = 60) that consisted of 4066 unique locations. These data were subset between pre-and post-independence periods and between 44 and 32 catbirds, and 56 and 49 wood thrushes, respectively. On average, individuals were tracked for 41 days (range = 2 to 88 days). Excluding individuals that died on day 1, 69% of catbirds and 86% of wood thrushes survived. From these data, we generated BB-based home ranges for catbirds and wood thrushes during pre- and post-independence periods (see Fig. 2).

Mean time-integrated Brownian bridge-derived probability density functions (PDF) for fledgling gray catbirds and wood thrushes during pre-independence (a and b, respectively), and post-independence (c and d, respectively) periods after fledging during the breeding seasons from 2012 to 2014 in and around Newark, Delaware, USA. All panels show same area in relation to scale bar in panel d

We found that the relative proportions of land cover classes within home ranges were independent of each other both within and between catbirds and wood thrushes during pre-independence (\( {\mathcal{X}}^2 \) = 70.55, df = 9, P < 0.00001) and post-independence (\( {\mathcal{X}}^2 \) = 953.8, df = 12, P < 0.00001; Table 1 and Fig. 3).

Relative proportions of 16 land cover classes (weighted mean ± SE) within post-fledgling home ranges used by gray catbirds (GRCA; gray bars) and wood thrushes (WOTH; brown bars) during pre- and post-independence periods during the breeding seasons from 2012 to 2014 in and around Newark, Delaware, USA

We detected significant differences between species among land cover classes (PBtest = 165.1, nsim =1000, P < 0.001) that the use of deciduous forest area was five times more frequent by wood thrushes (0.66 ± 0.10 km2) compared to catbirds (0.013 ± 0.018 km2). Catbird home ranges contained a greater amount of roads (0.12 ± 0.03 km2) compared to wood thrushes (0.08 ± 0.02 km2; PBtest = 3.82, nsim =1000, P < 0.05). Furthermore, we detected a significant post-fledging period × land cover class × species effect (PBtest = 126.6, nsim =1000, P < 0.001), where the area of deciduous forest used by wood thrushes was 5.3 times greater than for catbirds during post-independence (t.ratio = − 10.34, P < 0.0001; Fig. 4). Catbirds occupied home ranges that contained 1.8 times more road area compared to wood thrushes during the post-independence (t.ratio = 2.77, P < 0.04; Fig. 4). Additionally, we detected a significant fate × land cover class × species effect (PBtest = 21.5, nsim =1000, P < 0.04), which showed that, of birds that survived, wood thrushes used deciduous forest area 4.9 times more often than catbirds (t.ratio = − 15.2, P < 0.0001; Fig. 4). Although we detected a marginally significant post-fledging period × fate × species effect (PBtest = 3.43, nsim =1000, P = 0.078), post-hoc pairwise comparisons indicated that catbirds and wood thrushes used areas similarly between fates within pre- and post-fledging periods (t.ratios ranged between − 2.21 and 1.40, P > 0.35, in all cases). Moreover, we found no interactive effects of post-fledging period × fate × land cover class × species (PBtest = 15.5, nsim =1000, P = 0.19).

Comparison of the habitat area used (km2) in post-fledgling home ranges for 12 land cover classes (weighted mean ± SE) by gray catbirds (GRCA; gray bars) and wood thrushes (WOTH; brown bars) for pre- and post-independence periods during the breeding seasons from 2012 to 2014 in and around Newark, Delaware, USA

Wood thrushes had higher CV values for the area used (km2) within home ranges than catbirds within all land cover classes except Evergreen Forest, Cultivated Crops, and Scrub/Shrub habitat (Fig. 5). In general, both species had lower CV values during post-independence compared to pre-independence periods (Fig. 5). The computed difference in CV of area used (km2) between pre- and post-independence periods (∆CV) showed how the variance decreased for fledglings moving after post-independence compared to pre-independence periods in all cases except for the amount of Evergreen Forest in wood thrush home ranges (Fig. 5). We found that ∆CV was lower in Developed Low, Medium, and High Intensity land cover classes compared to others (Fig. 5). In general, catbirds had greater ∆CV compared to wood thrushes, except for Cultivated Crops and Evergreen Forest land cover classes. These results suggest that both wood thrush and catbird home ranges became more similar, respectively among individuals when after becoming independent of parental care. However, this pattern was more pronounced in the wood thrush.

Coefficient of variation (CV) and difference of the coefficient of variation (∆CV) between pre- and post-independence periods of area used (km2) within home ranges for 12 land cover classes for gray catbirds (GRCA; gray bars) and wood thrushes (WOTH; brown bars) during the breeding seasons from 2012 to 2014 in and around Newark, Delaware, USA

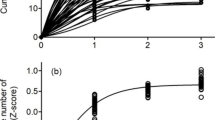

Analyzing the movement metrics underlying habitat use patterns while accounting for all potential interaction terms revealed that movement metrics including home range size, path length, total displacement, and net displacement were all similar between catbirds and wood thrushes (PBtest < 1.73, nsim = 1000, P > 0.19 in all cases; Table 2). However, despite a lack of differences between species, we did uncover more generalized patterns between post-fledging periods. For example, we found home range size was 6.9 times greater during post-independence (1.57 ± 0.20 km2) compared to pre-independence (0.23 ± 0.04 km2) periods (PBtest = 42.3, nsim = 1000, P < 0.001; Fig. 6a). Path length differed between pre- and post-fledging periods (PBtest = 109.4, nsim = 1000, P < 0.001), where post-independence path length (132.3 ± 4.5 m) was double the path length during pre-independence (63.5 ± 2.5 m; Fig. 6b). Total displacement moved was greater during post-independence (3989 ± 331 m) than pre-independence (945.4 ± 59 m) periods (PBtest = 86.3, nsimn = 1000, P < 0.001; Fig. 6c). Additionally, the net displacement was also greater during post-independence (720.7 ± 80.4 m) than during pre-independence (174.5 ± 25.5 m) periods (PBtest = 44.2, nsim = 1000, P < 0.001; Fig. 6d).

Discussion

We demonstrated how two species of post-fledging Nearctic-Neotropical migratory birds with similar evolutionary- and life-history characteristics, yet differing habitat specialization characteristics responded uniquely in their movement and habitat use patterns within an urbanized landscape. In our study, we compared the catbird and wood thrush that are known to exhibit generalist and specialist habitat-selection proclivities, respectively. Our expectations that catbirds would use areas with less forest and more roads compared to wood thrushes, were supported by our results of estimated home ranges of both species in relation to a representative urbanized landscape within our study area, located in the coastal mid-Atlantic United States, embedded within the megalopolis extending from Boston, Massachusetts to Washington, D. C., USA [80, 81].

We found that catbirds used areas with more developed land cover (e.g., more roads in particular) than wood thrushes, and in contrast, wood thrushes used much greater areas of deciduous forest during the entire post-fledging period. These patterns also differed between pre- and post-independence, when fledglings left natal patches, navigating through the urbanized landscape of our study area. These results are suggestive of how species-specific behavior (e.g., tolerant or avoidant behavior of fledglings to areas of higher road density) may have subsequent repercussions on post-fledgling survival found in other recent studies [66]. However, after examining the variance (CV and ∆CV), we were surprised to find that the wood thrush, typically known as a forest interior specialist, showed greater variation in the area of land cover classes comprising individuals’ home ranges compared to catbirds which are generally more of an edge species and habitat generalist. Since we found this pattern to occur in both pre- and post-independence periods, this finding, in part, may be due to the natal areas of sampled birds. Wood thrushes were sampled from a wider set of geographic locations compared to catbirds within our study area, which could give rise to more variation in surrounding habitat types, and hence land cover classes that get included within estimated home ranges. Nonetheless, the reduction we found in CV of area used among land cover classes for both catbirds and wood thrushes during post-independence indicates that home ranges became more similar during this period among individuals.

Our results supported our expectations, and are important in helping to better understand how habitat use during the post-fledging period within the annual cycle, is related to the effects of urbanization on songbird populations [82]. Patterns in basic movement metrics of wood thrushes such as mean net displacement (m) were similar to previous studies of post-fledging movement [83,84,85]; however, estimates of home range size differed considerably. For example, [83] estimated home range sizes of fledgling wood thrushes ranged between 0.026 and 0.25 km2 whereas in our study estimated home range sizes ranged between 0.019 and 8.7 km2. In light of the development of improved analysis methods for estimating habitat use [69, 72, 86], observed differences are of course, understandable. Although these ranges overlap at the lower end, the discrepancy in differing upper ranges is likely due to differences in the landscapes and habitat composition between the two studies. Anders et al. [83] study took place in a contiguous mature forest compared to our study area’s fragmented urban landscape. Additionally, it has been recently shown that differences can likely arise when using different estimators of home range size [69]. Moreover, both simulation-based [87], and empirical studies have demonstrated support for how differences in landscape permeability within urban areas can influence bird movement [88,89,90].

Life within urbanized landscapes is often difficult for breeding birds [36, 91, 92], particularly due to inherent losses of suitable breeding habitat [93]. However, not all species respond to direct and indirect effects of urbanization similarly, likely due to complex and interacting differences among evolutionary- and life-history traits, habitat requirements, and behavioral and phenotypic flexibility [94]. In particular, achieving the habitat requirements (e.g., availability and arrangement) for post-fledging birds to forage, avoid mortality risks, and survive until migratory dispersal can be challenging in urban landscapes [95, 96].

How generalist and specialist species respond to anthropogenic factors (e.g., land cover change related to urbanization) continues to be an important area of ecological and biological study across taxa [97,98,99,100] including birds [101,102,103]. While there are obvious conservation-related motivations for this area of inquiry, improving our fundamental understanding of how habitat generalization and specialization influences community assemblage patterns and species’ ability to adapt to environmental change, in general, remain critical aspects of ecological research [104,105,106,107]. Defining if a species is a habitat generalist or specialist remains challenging, however findings from recent studies attempting to better understand how the degree of habitat specialization influence species’ response to land cover change have made notable efforts [105, 107]. For example, after using the continent-wide data set on breeding birds in North America [108] and classified land cover data (250-m resolution), to calculate a species specialization index (SSI) using methods from [104, 106] estimated SSI for gray catbirds (1.10) and wood thrushes (1.48), with a higher SSI value indicating a greater degree of specialization. Given known scale-dependent effects of estimating the degree of habitat specialization [105], we would predict that in the more heavily fragmented, urbanized, and densely-populated New England and mid-Atlantic region of the United States, the difference between catbird and wood thrush SSI may become even more pronounced. In another recent study, [109] found that wood thrush populations at the landscape-scale responded negatively to decreased landscape quality as a function of increased habitat loss and fragmentation (while controlling for amount of habitat) due to urbanization. Collectively, these results support findings from our study, and suggest that future research focusing on local and regional responses of generalist catbirds and more specialized wood thrushes are warranted.

Increased space use within the urban matrix, for example, can be inherently linked to reduced post-fledging survival probability, due to the increase in exposure to both natural and anthropogenic mortality factors [110,111,112]. Adalsteinsson et al. [66] found that post-fledging survival was higher for wood thrushes than gray catbirds. However, both species experienced an increased risk of mortality due to anthropogenic factors during the post-independence period. This makes sense as it is the period when fledglings are no longer requiring parental provisioning, and are leaving their natal forest patches to explore potentially hostile matrix environments for their first time. Our estimates of habitat use during post-independence corroborate patterns of exposure to anthropogenic mortality factors, as measured by the differences between catbirds and wood thrushes in their use of areas with roads. The resulting number of road crossing events which can be thought of as a proxy for anthropogenic mortality factors, was correlated with respective survival estimates during the post-independence period within our study area [66]. These results provide insight into the mechanisms by which fledglings during post-independence mitigate a naturally incurred higher risk of mortality potentially, due to the increased probability of encountering developed land cover and roads through differential habitat use behaviors. These findings can help lay the groundwork to enable future empirical-based models to help predict how populations of migratory landbirds respond to increasing rates of habitat loss and fragmentation that will likely result from imminent increases in the rate of urbanization over the next several decades.

As increasing rates of urbanization are predicted to increase adverse effects on ecosystems [113], species that depend on critical non-urban breeding habitat such as migratory Neotropical birds are also predicted to experience concomitant declines [114,115,116]. Given equivocal results as to the effects of urbanization on forest-breeding bird populations from previous studies [109, 117], continued research in this area seems warranted. To manage increasingly urbanized ecosystems, and design landscapes to mitigate potential negative effects, studies ought to continue investigating how species respond, and adapt to both direct and indirect anthropogenic effects of urbanization including loss of habitat, habitat fragmentation, and increased road densities.

Conclusions

Given predicted increasing rates of urbanization, understanding how direct and indirect linkages between anthropogenic factors and declining migratory songbird species is important. Our study highlights the continuing need to explore the understudied post-fledging period to tease apart how urbanization effects on individuals can play an important role in habitat use. We found that habitat use decisions by two species of post-fledging Nearctic-Neotropical species differing in their degree of habitat specialization, and exhibiting differential tolerance for urbanization responded according to our basic predictions. The wood thrush, a forest interior specialist, used more forest habitat within post-fledging home ranges and avoided roads compared to the more urban-tolerant and generalist species, the gray catbird.

Abbreviations

- ∆CV:

-

Delta coefficient of variation

- BB:

-

Brownian bridge

- BBMM:

-

Brownian bridge movement model

- CV:

-

Coefficient of variation

- NLCD:

-

National land cover data

- PBtest:

-

Parametric bootstrap test

- PDF:

-

Probability density function

- SSI:

-

Species specialization index

- TIGER:

-

Topologically Integrated Geographic Encoding and Referencing

References

Kernohan BJ, Gitzen RA, Millspaugh JJ. Chapter 5 - Analysis of Animal Space Use and Movements. Radio Tracking and Animal Populations. San Diego: Academic Press; 2001. p. 125–66.

Nathan R, Getz WM, Revilla E, Holyoak M, Kadmon R, Saltz D, et al. A movement ecology paradigm for unifying organismal movement research. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. National Acad Sciences. 2008;105:19052–9.

Esser AH. The importance of defining spatial behavioral parameters. In: Esser AH, editor. Behavior and environment: the use of space by animals and men. New York: Plenum Press; 1971. p. 1–9.

Groom C, White NE, Mitchell N, Roberts JD, Mawson P. Assessing the spatial ecology and resource use of a mobile and endangered species in an urbanized landscape using satellite telemetry and DNA faecal metabarcoding. Ibis. Wiley Online Library. 2017;159:390–405.

Marzluff JM, Millspaugh JJ, Hurvitz P, Handcock MS. Relating resources to a probabilistic measure of space use: forest fragments and Steller’s Jays. Ecology. Ecological Society of America. 2004;85:1411–27.

Shepard ELC, Wilson RP, Rees WG, Grundy E, Lambertucci SA, Vosper SB. Energy landscapes shape animal movement ecology. Am Nat. journals.uchicago.edu. 2013;182:298–312.

Wauchope HS, Shaw JD, Varpe Ø, Lappo EG, Boertmann D, Lanctot RB, et al. Rapid climate-driven loss of breeding habitat for Arctic migratory birds. Glob Chang Biol. Wiley Online Library. 2017;23:1085–94.

Thompson MM, Coe BH, Congdon JD, Stauffer DF, Hopkins WA. Nesting Ecology and Habitat Use of Chelydra serpentina in an Area Modified by Agricultural and Industrial Activity. Herpetol Conserv Biol. pdfs.semanticscholar.org. 2017;12:292–306.

Allouche S, Gaudin P. Effects of avian predation threat, water flow and cover on growth and habitat use by chub, Leuciscus cephalus, in an experimental stream. Oikos. Munksgaard International Publishers. 2001;94:481–92.

Martínez D, García D. Disentangling habitat use by frugivorous birds: constant interactive effects of forest cover and fruit availability. Basic Appl Ecol. . Elsevier. 2015;16:460–8.

Neu CW, Byers CR, Peek JM. A technique for analysis of utilization-availability data. J Wildl Manag. 1974;38:541–5.

Mysterud A, Ims RA. Functional responses in habitat use: availability influences relative use in trade-off situations. Ecology. Wiley Online Library. 1998;79:1435–41.

Cooper NW, Sherry TW, Marra PP. Modeling three-dimensional space use and overlap in birds. Auk. American Ornithological Society. 2014;131:681–93.

Boelman NT, Gough L, Wingfield J, Goetz S, Asmus A, Chmura HE, et al. Greater shrub dominance alters breeding habitat and food resources for migratory songbirds in Alaskan arctic tundra. Glob Chang Biol. Wiley Online Library. 2015;21:1508–20.

Masden EA, Haydon DT, Fox AD, Furness RW, Bullman R, Desholm M. Barriers to movement: impacts of wind farms on migrating birds. ICES J Mar Sci. Oxford University Press. 2009;66:746–53.

Boggie MA, Mannan RW. Examining seasonal patterns of space use to gauge how an accipiter responds to urbanization. Landsc Urban Plan. Elsevier. 2014;124:34–42.

Trierweiler C, Klaassen RHG, Drent RH, Exo K-M, Komdeur J, Bairlein F, et al. Migratory connectivity and population-specific migration routes in a long-distance migratory bird. Proc Biol Sci. rspb.royalsocietypublishing.org. 2014;281:20132897.

Hobson KA, Kardynal KJ. Western Veeries use an eastern shortest-distance pathway: new insights to migration routes and phenology using light-level geolocators. Auk Am Ornithol Soc. American Ornithological Society. 2015;132:540–50.

Cooper NW, Hallworth MT, Marra PP. Light-level geolocation reveals wintering distribution, migration routes, and primary stopover locations of an endangered long-distance migratory songbird. J Avian Biol. Wiley Online Library. 2017;48:209–19.

Hewson CM, Thorup K, Pearce-Higgins JW, Atkinson PW. Population decline is linked to migration route in the Common Cuckoo. Nat Commun. nature.com. 2016;7:12296.

La Sorte FA, Fink D, Hochachka WM, Aycrigg JL, Rosenberg KV, Rodewald AD, et al. Documenting stewardship responsibilities across the annual cycle for birds on US public lands. Ecol Appl. Wiley Online Library. 2015;25:39–51.

Runge CA, Watson JEM, Butchart SHM, Hanson JO, Possingham HP, Fuller RA. Protected areas and global conservation of migratory birds. Science. science.sciencemag.org. 2015;350:1255–8.

Lens L, Dhondt AA. Effects of habitat fragmentation on the timing of rested it Parus cristatus natal dispersal. Ibis. Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 1994;136:147–52.

Anders AD, Dearborn DC, Faaborg J, Iii FRT. Juvenile survival in a population of Neotropical migrant birds. Conserv Biol. Conserv Biol. 1997;11:698–707.

King DI, Degraaf RM, Smith M-L, Buonaccorsi JP. Habitat selection and habitat-specific survival of fledgling ovenbirds (Seiurus aurocapilla). J Zool. Wiley Online Library. 2006;269:414–21.

Jenkins JMA, Hart M, Eggert LS, Faaborg J. Sex-specific movements in Postfledging juvenile ovenbirds (Seiurus aurocapilla). Wilson J Ornithol. The Wilson Ornithological Society. 2017;129:846–50.

Rockwell SM, Wunderle JM Jr, Sillett TS, Bocetti CI, Ewert DN, Currie D, et al. Seasonal survival estimation for a long-distance migratory bird and the influence of winter precipitation. Oecologia. Springer. 2017;183:715–26.

Cohen EB, Barrow WC, Buler JJ, Deppe JL, Farnsworth A, Marra PP, et al. How do en route events around the Gulf of Mexico influence migratory landbird populations? Condor. American Ornithological Society. 2017;119:327–43.

Gómez C, Bayly NJ, Norris DR, Mackenzie SA, Rosenberg KV, Taylor PD, et al. Fuel loads acquired at a stopover site influence the pace of intercontinental migration in a boreal songbird. Sci Rep. nature.com. 2017;7:3405.

Paxton KL, Moore FR. Connecting the dots: stopover strategies of an intercontinental migratory songbird in the context of the annual cycle. Ecol Evol. Wiley Online Library. 2017;7:6716–28.

Ruiz-Gutierrez V, Kendall WL, Saracco JF, White GC. Overwintering strategies of migratory birds: a novel approach for estimating seasonal movement patterns of residents and transients. J Appl Ecol. Wiley Online Library. 2016;53:1035–45.

Goodenough AE, Coker DG, Wood MJ, Rogers SL. Overwintering habitat links to summer reproductive success: intercontinental carry-over effects in a declining migratory bird revealed using stable isotope analysis. Bird Study. Taylor & Francis. 2017;64:433–44.

Colorado ZGJ, Rodewald AD. Patterns of change in body condition in wintering Neotropical-Nearctic migratory birds in shaded plantations in the Andes. Agrofor Syst. Springer Netherlands. 2017;91:1129–37.

Cox WA, Thompson FR, Cox AS, Faaborg J. Post-fledging survival in passerine birds and the value of post-fledging studies to conservation. J Wildl Manage. Wiley Online Library. 2014;78:183–93.

Panjabi AO, Blancher PJ, Easton WE, Stanton JC, Demarest DW, Dettmers R, et al. The Partners in Flight handbook on species assessment Version 2017 [Internet]. Partners in Flight; 2017. Available from: https://pubs.er.usgs.gov/publication/70191331

Aronson MFJ, La Sorte FA, Nilon CH, Katti M, Goddard MA, Lepczyk CA, et al. A global analysis of the impacts of urbanization on bird and plant diversity reveals key anthropogenic drivers. Proc R Soc B. The Royal Society. 2014;281:20133330.

Fahrig L. Ecological responses to habitat fragmentation per se. Annu Rev Ecol Syst. Annual Reviews. 2017;48:1–23.

Møller AP, Díaz M, Flensted-Jensen E, Grim T, Ibáñez-Álamo JD, Jokimäki J, et al. Urbanized birds have superior establishment success in novel environments. Oecologia. Springer. 2015;178:943–50.

Jokimäki J, Suhonen J, Jokimäki-Kaisanlahti M-L, Carbó-Ramírez P. Effects of urbanization on breeding birds in European towns: impacts of species traits. Urban Ecosyst. Springer US. 2016;19:1565–77.

Batáry P, Kurucz K, Suarez-Rubio M, Chamberlain DE. Non-linearities in bird responses across urbanization gradients: A meta-analysis. Glob Chang Biol [Internet]. Wiley Online Library; 2017. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.13964.

Bellocq MI, Leveau LM, Filloy J. Urbanization and Bird Communities: Spatial and Temporal Patterns Emerging from Southern South America. In: Ecology and Conservation of Birds in Urban Environments. Cham: Springer; 2017. p. 35–54.

Steven DDE. The influence of age on the breeding biology of the tree swallow Iridoprocne bicolor. Ibis. Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 1978;120:516–23.

Weeks HP. Nesting ecology of the eastern Phoebe in Southern Indiana. Wilson Bull. Wilson Ornithological Society. 1979;91:441–54.

Yackel Adams AA, Skagen SK, Savidge JA. Modeling post-fledging survival of lark buntings in response to ecological and biological factors. Ecology. Wiley Online Library. 2006;87:178–88.

Grüebler MU, Naef-Daenzer B. Survival benefits of post-fledging care: experimental approach to a critical part of avian reproductive strategies. J Anim Ecol. Wiley Online Library; 2010;79:334–341.

Eng ML, Stutchbury BJM, Burke DM, Elliott KA. Influence of forest management on pre- and post-fledging productivity of a Neotropical migratory songbird in a highly fragmented landscape. Can J For Res. NRC Research Press. 2011;41:2009–19.

Prum RO, Berv JS, Dornburg A, Field DJ, Townsend JP, Lemmon EM, et al. A comprehensive phylogeny of birds (Aves) using targeted next-generation DNA sequencing. Nature. nature.com. 2015;526:569–73.

Evans M, Gow E, Roth RR, Johnson MS, Underwood TJ. Wood thrush (Hylocichla mustelina). In: Poole A, editor. The birds of North America online. Ithica: Cornell Lab of Ornithology; 2011.

Smith RJ, Hatch MI, Cimprich DA, Moore FR. Gray catbird (Dumetella carolinensis). The Birds of North America Online Ithaca: Cornell Lab of Ornithology Available: http://bna.birds.cornell.edu/bna/species/167 Accessed. 2011;

Sauer JR, Niven DK, Hines JE, Ziolkowski DJ Jr, Pardieck KL, Fallon JE, et al. The North American Breeding Bird Survey, Results and Analysis 1966–2015. Laurel: USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center; 2017.

Erickson WP, Johnson GD, Young DP Jr. A summary and comparison of bird mortality from anthropogenic causes with an emphasis on collisions. USDA Forest Service General Technical Report PSWGTR-191. researchgate.net; 2005;1029–1042.

Loss SR, Will T, Loss SS, Marra PP. Bird–building collisions in the United States: estimates of annual mortality and species vulnerability. Condor. American Ornithological Society. 2014;116:8–23.

Hager SB, Cosentino BJ, Aguilar-Gómez MA, Anderson ML, Bakermans M, Boves TJ, et al. Continent-wide analysis of how urbanization affects bird-window collision mortality in North America. Biol Conserv. Elsevier. 2017;212:209–15.

Woods M, McDonald RA, Harris S. Predation of wildlife by domestic cats Felis catus in Great Britain. Mamm Rev. Wiley Online Library. 2003;33:174–88.

Dauphiné N, Cooper RJ. Impacts of free-ranging domestic cats (Felis catus) on birds in the United States: a review of recent research with conservation and management recommendations. Proceedings of the fourth international partners in flight conference: tundra to tropics. 2009;205–219. Available from: http://copa.acguanacaste.ac.cr:8080/handle/11606/657.

Loss SR, Will T, Marra PP. The impact of free-ranging domestic cats on wildlife of the United States. Nat Commun. nature.com. 2013;4:1396.

Fry DM. Reproductive effects in birds exposed to pesticides and industrial chemicals. Environ Health Perspect. ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. 1995;103(7):165–71.

Sanderfoot OV, Holloway T. Air pollution impacts on avian species via inhalation exposure and associated outcomes. Environ Res Lett. IOP Publishing. 2017;12:083002.

Robbins CS, Sauer JR, Greenberg RS, Droege S. Population declines in north American birds that migrate to the neotropics. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. National Acad Sciences. 1989;86:7658–62.

Both C, Bouwhuis S, Lessells CM, Visser ME. Climate change and population declines in a long-distance migratory bird. Nature. nature.com. 2006;441:81–3.

Schmidt KA. Information thresholds, habitat loss and population persistence in breeding birds. Oikos. Wiley Online Library. 2017;126:651–9.

Gibbs JP, Shriver WG. Estimating the effects of road mortality on turtle populations. Conserv Biol. Wiley Online Library. 2002;16:1647–52.

Brady SP, Richardson JL. Road ecology: shifting gears toward evolutionary perspectives. Front Ecol Environ. Wiley Online Library. 2017;15:91–8.

Erritzoe J, Mazgajski TD, Rejt Ł. Bird casualties on European roads—a review. Acta Ornithol. BioOne. 2003;38:77–93.

Benítez-López A, Alkemade R, Verweij PA. The impacts of roads and other infrastructure on mammal and bird populations: a meta-analysis. Biol Conserv. Elsevier. 2010;143:1307–16.

Adalsteinsson SA, Buler JJ, Bowman JL, D’Amico V, Ladin ZS, Gregory Shriver W. Post-independence mortality of juveniles is driven by anthropogenic hazards for two passerines in an urban landscape. J Avian Biol. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1111/jav.01555.

Martin TE, Geupel GR. Nest-monitoring plots: Methods for locating nests and monitoring success (Métodos para localizar nidos y monitorear el éxito de estos). J Field Ornithol. [Association of Field Ornithologists, Wiley]. 1993;64:507–19.

Rappole JH, Tipton AR. New harness design for attachment of radio transmitters to small passerines (Nuevo Diseño de Arnés para Atar Transmisores a Passeriformes Pequeños). J Field Ornithol. [Association of Field Ornithologists, Wiley]. 1991;62:335–7.

Walter WD, Onorato DP, Fischer JW. Is there a single best estimator? Selection of home range estimators using area-under-the-curve. Mov Ecol. 2015;3:10.

Bullard F. Estimating the home range of an animal: a Brownian bridge approach. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina; 1991.

Horne JS, Garton EO, Krone SM, Lewis JS. Analyzing animal movements using Brownian bridges. Ecology. Wiley Online Library. 2007;88:2354–63.

Van Nieuland S, Baetens JM, De Meyer H, De Baets B. An analytical description of the time-integrated Brownian bridge. Comput Appl Math. Springer. 2017;36:627–45.

Kie JG, Matthiopoulos J, Fieberg J, Powell RA, Cagnacci F, Mitchell MS, et al. The home-range concept: are traditional estimators still relevant with modern telemetry technology? Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. rstb.royalsocietypublishing.org. 2010;365:2221–31.

Homer C, Dewitz J, Yang L, Jin S, Danielson P, Xian G, et al. Completion of the 2011 National Land Cover Database for the conterminous United States—representing a decade of land cover change information. Photogramm Eng Remote Sensing. American Society for Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing. 2015;81:345–54.

U.S. Census Bureau. 2016 TIGER/Line Shapefiles (machine readable data files). U.S. Census Bureau. 2016.

Bates D, Maechler M, Bolker B, Walker S. lme4: Linear mixed-effects models using Eigen and S4. R package version 1.7. 2014;1–23.

Hothorn T, Bretz F, Westfall P. Simultaneous inference in general parametric models. Biom J. 2008;50:346–63.

Halekoh U, Højsgaard S. A kenward-roger approximation and parametric bootstrap methods for tests in linear mixed models–the R package pbkrtest. J Stat Softw. 2014;59:1–30.

Team RC. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2017.

Gottmann J. Megalopolis or the urbanization of the northeastern seaboard. Econ Geogr. [Clark University, Wiley]. 1957;33:189–200.

Morrill R. Classic map revisited: the growth of megalopolis. Prof Geogr. Blackwell Publishing Inc. 2006;58:155–60.

Lepczyk CA, La Sorte FA, Aronson MFJ, Goddard MA, MacGregor-Fors I, Nilon CH, et al. Global patterns and drivers of urban bird diversity. Ecology and conservation of birds in urban environments. Cham: Springer; 2017. p. 13–33.

Anders AD, Faaborg J, Thompson FR III. Postfledging dispersal, habitat use, and home-range size of juvenile wood thrushes. Auk. 1998:349–58.

Vega Rivera JH, Rappole JH, McShea WJ, Haas CA. Wood thrush Postfledging movements and habitat use in northern Virginia. Condor. Cooper Ornithological Society. 1998;100:69–78.

Vernasco BJ, Sillett TS, Marra PP, Ryder TB. Environmental predictors of nestling condition, postfledging movement, and postfledging survival in a migratory songbird, the Wood Thrush (Hylocichla mustelina). Auk. American Ornithological Society. 2017;135:15–24.

Demšar U, Buchin K, van Loon EE, Shamoun-Baranes J. Stacked space-time densities: a geovisualisation approach to explore dynamics of space use over time. Geoinformatica. Springer. 2015;19:85–115.

Hand BK, Cushman SA, Landguth EL, Lucotch J. Assessing multi-taxa sensitivity to the human footprint, habitat fragmentation and loss by exploring alternative scenarios of dispersal ability and population size: a simulation approach. Biodivers Conserv. 2014;23:2761–79.

Tremblay MA, St. Clair CC. Factors affecting the permeability of transportation and riparian corridors to the movements of songbirds in an urban landscape. J Appl Ecol. Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 2009;46:1314–22.

Baguette M, Blanchet S, Legrand D, Stevens VM, Turlure C. Individual dispersal, landscape connectivity and ecological networks. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc. 2013;88:310–26.

Evans BS, Kilpatrick AM, Hurlbert AH, Marra PP. Dispersal in the urban matrix: assessing the influence of landscape permeability on the settlement patterns of breeding songbirds. Front Ecol Evol. frontiersin.org. 2017;5:762.

Marzluff JM. Worldwide urbanization and its effects on birds. Avian ecology and conservation in an urbanizing world. Boston: Springer; 2001. p. 19–47.

Rodewald AD, Shustack DP. Consumer resource matching in urbanizing landscapes: are synanthropic species over-matching. Ecology. 2008;89:515–21.

Hoekstra JM, Boucher TM, Ricketts TH, Roberts C. Confronting a biome crisis: global disparities of habitat loss and protection. Ecol Lett. 2005;8:23–9.

Naef-Daenzer B, Grüebler MU. Post-fledging survival of altricial birds: ecological determinants and adaptation. J Field Ornithol. Wiley Online Library. 2016;87:227–50.

Whittaker K, Marzluff JM. Post-fledging mobility in an urban landscape. In: Warren PS, editor. Urban bird ecology and conservation. Studies in Avian Biology (no. 45). Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 2012. p. 183–198.

Seress G, Liker A. Habitat urbanization and its effects on birds. Acta Zool Academ Sci Hung. Hung. real.mtak.hu. 2015;61:373–408.

Futuyma DJ, Moreno G. The evolution of ecological specialization. Annu Rev Ecol Syst. Annual Reviews. 1988;19:207–33.

McKinney ML, Lockwood JL. Biotic homogenization: a few winners replacing many losers in the next mass extinction. Trends Ecol Evol. Elsevier. 1999;14:450–3.

Walters DM, Leigh DS, Bearden AB. Urbanization, sedimentation, and the homogenization of fish assemblages in the Etowah River basin, USA. The interactions between sediments and water. Netherlands: Springer; 2003. p. 5–10.

Gaublomme E, Hendrickx F, Dhuyvetter H, Desender K. The effects of forest patch size and matrix type on changes in carabid beetle assemblages in an urbanized landscape. Biol Conserv. Elsevier. 2008;141:2585–96.

Donnelly R, Marzluff JM. Relative importance of habitat quantity, structure, and spatial pattern to birds in urbanizing environments. Urban Ecosyst. 2006;9:99–117.

Devictor V, Julliard R, Couvet D, Lee A, Jiguet F. Functional homogenization effect of urbanization on bird communities. Conserv Biol. Wiley Online Library. 2007;21:741–51.

Gagné SA, Fahrig L. The trade-off between housing density and sprawl area: Minimising impacts to forest breeding birds. Basic Appl Ecol. Elsevier. 2010;11:723–33.

Julliard R, Clavel J, Devictor V, Jiguet F, Couvet D. Spatial segregation of specialists and generalists in bird communities. Ecol Lett. Wiley Online Library. 2006;9:1237–44.

Kneitel JM. Occupancy and environmental responses of habitat specialists and generalists depend on dispersal traits. Ecosphere. Wiley Online Library. 2018;9:e02143.

Pandit SN, Kolasa J, Cottenie K. Contrasts between habitat generalists and specialists: an empirical extension to the basic metacommunity framework. Ecology. Wiley Online Library. 2009;90:2253–62.

Martin AE, Fahrig L. Habitat specialist birds disperse farther and are more migratory than habitat generalist birds. Ecology [Internet]. Wiley Online Library. 2018; Available from: https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy.2428

Pardieck KL, Ziolkowski DJ Jr, Hudson MAR, Campbell K. North american breeding bird survey dataset 1966–2013, version 2013.0. US Geological Survey, Patuxent Wildlife Research Center< www pwrc usgs gov/BBS/RawData. 2014;

Taylor CM. The shape of density dependence in fragmented landscapes explains an inverse buffer effect in a migratory songbird. Sci Rep. nature.com. 2017;7:14522.

Ausprey IJ, Rodewald AD. Postfledging survivorship and habitat selection across a rural-to-urban landscape gradient. Auk. American Ornithological Society. 2011;128:293–302.

Vitz AC, Rodewald AD. Influence of condition and habitat use on survival of post-fledging songbirds. Condor. American Ornithological Society. 2011;113:400–11.

Balogh AL, Ryder TB, Marra PP. Population demography of gray catbirds in the suburban matrix: sources, sinks and domestic cats. J Ornithol. Springer-Verlag. 2011;152:717–26.

Seto KC, Güneralp B, Hutyra LR. Global forecasts of urban expansion to 2030 and direct impacts on biodiversity and carbon pools. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. National Acad Sciences. 2012;109:16083–8.

Rottenborn SC. Predicting the impacts of urbanization on riparian bird communities. Biol Conserv. Elsevier. 1999;88:289–99.

Blair R. The effects of urban sprawl on birds at multiple levels of biological organization. Ecol Soc. 2004;9:2–22.

Ladin ZS, D’Amico V, Baetens JM, Roth RR, Shriver WG. Predicting metapopulation responses to conservation in human-dominated landscapes. Front Ecol Evol. frontiersin.org. 2016;4:122.

Rodewald AD, Kearns LJ, Shustack DP. Consequences of urbanizing landscapes to reproductive performance of birds in remnant forests. Biol Conserv. 2013;160:32–9.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the help from the following people for their work in the field that included nest-searching, monitoring, and tracking fledglings: M. Sirch, D. Ecker, J. Harmon, D. Knauss, J. Curry, N. Hengst, A. Walter, J. Richardson, K. Serno, M. Walker, M. Gartland, S. O’Connor, Z. Rachell, and K. Pastirik. Thanks also goes to S. O’Connor for his help in preparing data. Additionally, we thank the land managers for their cooperation and allowing us access to study sites within Newark City Parks, New Castle County and Delaware State Parks, and Natural Lands Trust’s Peacedale Preserve.

Funding

Financial support of this research was provided by the University of Delaware Research Foundation (13A00832), University of Delaware Aeroecology Program, USDA McIntire Stennis, and a University of Delaware Graduate Research Fellowship. The funders did not provide any input into this study, and do not require approval of the manuscript prior to submission and publication.

Availability of data and materials

Upon reasonable request from the corresponding author, all data sets and materials will be shared.

Authors ’ contributions

This research paper was developed jointly by ZSL, WGS, SVN, and JAB. Field data collection was made by SAA and ZSL. The manuscript was drafted by ZSL and all coauthors contributed to editing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

Our study had permissions from Newark City Parks, New Castle County and Delaware State Parks, and Natural Lands Trust’s for access to sites. All birds in this study received US Geological Survey bands under permit number: 23475. All research protocols were approved and implemented following guidelines from University of Delaware’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Ladin, Z.S., Van Nieuland, S., Adalsteinsson, S.A. et al. Differential post-fledging habitat use of Nearctic-Neotropical migratory birds within an urbanized landscape. Mov Ecol 6, 17 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40462-018-0132-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40462-018-0132-6