Abstract

Background

There is increasing evidence that the substantial global burden of disease for tuberculosis unfolds in concert with dimensions of common mental disorders. Person-centred care holds much promise to ameliorate these comorbidities in low-to-middle income countries (LMICs) and emerging economies. Towards this end, this paper aims to review 1) the nature and extent of tuberculosis and common mental disorder comorbidity and 2) person-centred tuberculosis care in low-to-middle income countries and emerging economies.

Main text

A scoping review of 100 articles was conducted of English-language studies published from 2000 to 2019 in peer-reviewed and grey literature, using established guidelines, for each of the study objectives. Four broad tuberculosis/mental disorder comorbidities were described in the literature, namely alcohol use and tuberculosis, depression and tuberculosis, anxiety and tuberculosis, and general mental health and tuberculosis. Rates of comorbidity varied widely across countries for depression, anxiety, alcohol use and general mental health. Alcohol use and tuberculosis were significantly related, especially in the context of poverty. The initial tuberculosis diagnostic episode had substantial socio-psychological effects on service users. While men tended to report higher rates of alcohol use and treatment default, women in general had worse mental health outcomes. Older age and a history of mental illness were also associated with pronounced tuberculosis and mental disorder comorbidity. Person-centred tuberculosis care interventions were almost absent, with only one study from Nepal identified.

Conclusions

There is an emerging body of evidence describing the nature and extent of tuberculosis and mental disorders comorbidity in low-to-middle income countries. Despite the potential of person-centred interventions, evidence is limited. This review highlights a pronounced need to address psychosocial comorbidities with tuberculosis in LMICs, where models of person-centred tuberculosis care in routine care platforms may yield promising outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Tuberculosis (TB) remains a significant cause of the global disease burden, especially among disadvantaged populations. In 2018, approximately 10 million people developed clinical disease, of whom about half a million new cases were rifampicin resistant. 1.3 million people co-infected with HIV and 300 000 without HIV died [1]. The inextricable relationship between TB and mental disorders is well known although less well-researched. Mental illnesses such as anxiety, mood and addiction disorders may have a high comorbidity rate among people suffering from TB [2,3,4], possibly with multidirectional relationships. Mental and substance use disorders increases risk factors to TB disease progression, such as tobacco smoking and poor nutrition, often compounded by additional conditions such as diabetes and HIV infection [2].

Common mental disorders (CMD), including substance abuse, are key mechanisms in medication adherence behaviour [5]. Alcohol use raises the risk of transmission due to patterns of social behaviour (i.e. increased exposure in congregate settings like bars), impairing the immune system and, raising the odds for infection [6]. Stigma in relation to mental illness and TB creates significant barriers to the prevention and cure of TB in many communities. This includes the composite of stigmatising effects of comorbidity between TB, mental disorders and stigmatised diseases such as HIV [7]. In short, both proximal and distal associations between TB and CMDs unfold within multiple biological and psychosocial causal pathways, even though these mechanisms remain under-researched [3]. The bulk of TB diseases is experience in low-to-middle income countries and emerging economies (BRICS: Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) [1]. However, there limited research that suggests that treatment of psychological aspects of TB may lead to improved clinical outcomes.

In India, psychotherapy during treatment resulted in improved adherence, treatment and cure outcomes [8]; group-based psychological support for patients with multidrug resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) in Peru improved treatment outcomes [9]; and in Ethiopia, ‘TB clubs’ both reduced stigma and improved treatment outcomes among patients [10], and an educational and psychological intervention improved treatment adherence [11].

The need to comprehend and address the TB-mental illness nexus has become more pronounced in low-to-middle income countries (LMICs) against the drive towards more holistic, intersectoral, person-centred health systems [12], backed by the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [13]. Following these directives, there is a pressing need to develop and refine evidence-based interventions towards improving person-centred care in addressing TB and common mental disorder comorbidity. There is however a distinct gap in current literature that systematically describes and examines the LMIC epidemiology of TB and mental disorders, as well as best practices in addressing this complex comorbid condition in LMIC health systems. The present study is located within a larger research consortium brought together to address key challenges plaguing health systems in sub-Sahara African countries (ASSET: heAlth System StrEngThening in sub-Saharan Africa), funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) in the United Kingdom [14]. One of the research packages of this programme focuses on developing person-centred care (PCC), especially in the contexts of comorbidities between TB and mental disorders.

PCC is an important ideal for TB treatment and care, a disease with a long and damaging social history, the diagnosis of which causes profound stigma, marginalisation and harm to the sense of self and personhood [15] – especially in conjunction with mental disorders [3]. Person-centred interventions have yielded significant benefits in improving psychological well-being and positive effects on behavioural symptoms and treatment adherence in dementia care [16,17,18], with promising effects on a range of outcomes in other kinds of clinical care [19, 20]. Nonetheless, the effectiveness of person-centred approaches to TB care is yet to be systematically and robustly investigated, especially in LMICs. It remains to be determined which principles and dimensions of PCC could improve TB care outcomes, but for the purposes of this review we focus on the concepts of person narrative, care collaboration and continuity. Person narrative focuses on decision-making based on rich information about the subjective experiences and attitudes of the patient, beyond biomedical symptoms; care collaboration includes the degree of collaboration between caregiver and patient during assessment, decision-making and care planning; and continuity refers to care as an on-going process that, in conjunction with person narrative, can be adapted, revised and reinterpreted [21].

We report a scoping review to inform the development of a person-centred package of TB care in primary healthcare (PHC) clinics in rural South Africa [14]. The objectives of the scoping review are two-fold:

-

1.

To describe the nature and extent of TB and common mental (anxiety, mood) and substance use disorder comorbidity in LMICs and the BRICS region.

-

2.

To explore person-centred care approaches to TB and mental and substance use disorder comorbidities in LMICs and the BRICS region.

Methods

Key definitions

There is no universally accepted, unified definition for person-centred care (PCC) [22, 23]. The term is often used interchangeably with related concepts such as “patient participation”, “patient empowerment” and “patient-centredness” [22,23,24,25,26]. Despite conceptual congruence in terms of dimensions such as a holistic perspective on the patient’s illness experience, an enabling collaborative therapeutic alliance between care giver and receiver [23, 24], and values such as empathy and respect [25], PCC has important distinctions. Approaches such as patient-centred care focuses on interactions in terms of visits and contact episodes; disease management; comorbidity as multiple diseases; body systems as distinct; professionally defined coding; and the evolution of disease. PCC, on the other hand, highlights interrelationships over time; illness episodes in a life-course perspective; the interrelated nature of body systems, diseases and morbidity; coding systems that allow for service user concerns; and considers both the evaluation of disease and people’s illness experience [27]. Person-centredness in care aims to understand 1) a person’s subjective experiences and interpretations of illness by considering psychosocial dimensions alongside biomedical symptomology, 2) adhere to the centrality of shared decision-making and parity, and 3) the primacy of relationships in care and treatment [28].

Study design and literature search strategies

A scoping review was conducted in line with criteria outlined by Arksey and O’Malley [29] and the Johanna Briggs Institute [30]. The following steps were followed: 1) Clear research objectives were developed and refined among research team members, following a brief review of key literature; 2) Relevant studies were identified by members of the research team; 3) Key studies were selected by members of the research team; 4) Data extracted from selected studies were charted; 5) Findings were collated, thematically analysed and reported using Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) [31].

Study selection and data abstraction

The search included English-language studies published within the period 2000–2019 in peer-reviewed and grey literature. From May to October 2018, two researchers (AvR and AD) independently searched PubMed Health Source (Academic/Nursing Edition); MEDLINE; PsychARTICLES; Psychinfo; the World Health Organization website; Google and Google Scholar. Different iterations of search terms where used in combination for each research objective (Table 1). For example, for Objective 1, the terms tuberculosis OR TB AND mental disorders OR mental illness OR mental health were entered, with the limiters Abstract, Publication date from 2000/01/01 to 2018/12/31, English, Adult: 19+ years, Adult: 19–44 years. For a list of all search terms and limiters employed see Table 1. The reference lists of key publications with high relevance were also searched, and PubMed’s similarity function was used to find articles excluded by the search terms. Two researchers independently reviewed the titles of search results for appropriateness, followed by a review of article abstracts. Where differences between the two researchers were noted, a third researcher was consulted. The inclusion criteria were: evidence from LMICs and BRICS countries, published since year 2000 and, and focused on both TB and mental disorders. The citations of these initial searches were imported into Endnote X9 (bibliography management software) [32] and exported to systematic review application Rayyan [33] for management and review. These systematic steps are presented in PRISMA flowchart format [34]. Once a final list of relevant articles was identified for each research objective, electronic versions were imported into NVivo version 12.1 (a qualitative data analysis software aiding thematic analysis of literature or qualitative research) [35] for management. A thematic analysis of the final group of articles were conducted in order to generate a narrative account of existing literature relevant to the two research objectives [29].

Results

For Objective 1, a total of 868 articles were initially identified (see Fig. 1). After screening the titles and abstracts for appropriateness, 737 articles were excluded because: The scope of the article did not include TB and mental disorders; did not focus on LMICs or BRICS; fell outside the 2000–2019 time limit; did not focus on adults. In the next phase, 131 articles were screened in full, using the same limiters, resulting in the exclusion of 31 articles. Thus 100 articles were included in the thematic analysis.

In terms of Objective 2, an initial number of 357 articles were identified (Fig. 2). After title and abstract screening, 157 articles were excluded because: The scope of the article did not include person-centred/patient-centred/community-centred approaches to TB care; did not focus on LMICs or BRICS; fell outside the 2000–2019 time limit; did not focus on adults. Thirty-two articles were excluded following full-text review, with only two papers included in the thematic analysis.

Several themes emerged during analysis. Four broad TB/mental disorder comorbidities were described in the literature, namely alcohol use and TB, depression and TB, anxiety and TB, and general mental health and TB (meaning that no specific disorders or psychiatric symptoms were identified). Studies generally did not include a clinical psychiatric diagnosis according to international guidelines, instead depending on measures such as quality of life as a proxy for mental wellness, or measurements of mental distress. Therefore, these studies did not strictly focus on TB and mental health comorbidities, but rather on the nexus between TB disease and psychological symptomology. For the different comorbidities, sub-themes that emerged included Comorbid TB and mental illness symptom rates; Associations between TB and mental illness symptoms; TB disease progression and mental illness symptoms; and Factors influencing relationships between TB and mental illness symptoms.

Comorbid TB and mental illness symptom rates

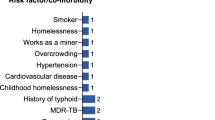

Rates of mental illness symptoms among TB patients were collated according to depressive symptoms, anxiety, alcohol use, and general mental health (Table 2). Studies that did not specify depression, anxiety or alcohol use – for instance psychological distress – were included under general mental health. Prevalence of depressive symptoms varied dramatically from 9% in Zambia [59] to 84% in India [46]. Likewise anxiety-related symptoms from 2% in India [46] to 47% in Pakistan [43] – gender differences were not widely explored. Alcohol use was measured in a variety of ways: questions on alcohol use habits, references to alcoholism, and use of Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT). Indications of harmful alcohol use ranged from 4% in Kazakhstan to 67% in Estonia [81]. Men were far more likely to engage in harmful alcohol use.

Associations between TB and mental illness

Several studies explored associations between mental illness symptoms and TB disease. One metanalysis of the period between 2000 and 2014 suggested that as alcohol consumption increases, so does the risk of contracting TB and alcohol-attributable TB mortality. The study estimated that alcohol consumption was responsible for 17% of TB incidence and 15% of TB mortality [98]. The likelihood of TB treatment non-adherence is increased by heavy alcohol use [41, 65, 70, 97]. Alcohol use intersects with TB biologically (through immunosuppression) and socially (increased exposure in closed, poorly ventilated spaces such as taverns and bars) [94, 98]. Further, both alcohol use and TB are “diseases of poverty”, compounding risk in poorer people [94, 99]. TB patients who use alcohol are perceived to be “difficult” by healthcare workers, poorly cooperative and challenging to manage [100]. Patients with TB who also use alcohol were more likely to exhibit risky behaviours and are at a higher risk of contracting HIV [69]. The combination of HIV co-infection and heavy alcohol use prolongs the duration of cough prior to presentation at a health facility [41].

In terms of the influence of the disease on emotional well-being, several studies highlighted impact of a TB diagnosis on mental health. The period following diagnosis is significantly associated with subsyndromal depression, and brief depressive episodes [4]. This emotional toll may be mediated more through role limitation and increased mental distress than physical symptoms [39]. Social stigma and isolation may entrench such feelings [54, 101,102,103,104]. A TB diagnosis is associated with a loss of self-esteem, fears of rejection and infecting loved ones [105]. Psychological distress appears to be exacerbated by heavy alcohol use, female gender, previous episodes of TB, and increased morbidity [41]. A Peruvian study reported that people suffering both from TB and HIV expressed a need for support from a psychologist with shortages of mental health professionals impacting negatively on patients’ mental health [103]. These effects are amplified in MDR-TB. A study evaluating the quality of life associated with MDR-TB found that patients suffered from severe physiological, financial and psychological challenges, which persisted beyond treatment completion, and resulted in survival adaptation, poor general health, loss of freedom and agency, and a lack of social participation [102].

TB disease progression and mental illness symptoms

Diagnosis phase and mental illness

The exact causal pathways between TB disease and mental illness are unclear. Few studies have systematically explored longitudinal dimensions between mental illness symptoms and the progression of TB disease, where the diagnosis and treatment initiation stages pose substantial risk for mental illnesses. At diagnosis the following are common: anxiety related symptoms [47, 104], related to fears of death, serious illness, and limited knowledge of TB disease [106, 107], depressive feelings, feelings of worry and embarrassment as well as shame [105]. A TB diagnosis can lead to shock, anxiety and shame, with high levels of psychological distress [55, 103, 107]. At this phase, psychological issues are more severe with family, community and social issues becoming more salient during and after the treatment phase [108]. One study found TB patients with elevated levels of psychological distress were more likely to die during treatment than those with lower levels [41].

Additionally, the risk of mental illness is greater in MDR-TB. MDR-TB patients have a high likelihood of having depression, throughout the illness experience [39]. One study suggested that mental, social and physical challenges posed by MDR-TB were related to deteriorating health-related quality of life scores as the disease progresses [39]. A review of studies on MDR-TB reported that MDR-TB patients face a range of psychological issues, including emotions of hopelessness and fear, accentuated by being conscious of the finality of MDR-TB treatment as a last option [108].

Treatment initiation phase and mental illness

TB patients with depressive symptoms are more likely to experience negative TB outcomes than those without such symptoms [38]. Several studies involving mental health measures suggest TB treatment adherence reduces mental illness symptoms. Mental health domains of health-related quality of life assessments have shown to significantly improve following initial phases of TB treatment [39, 101, 109,110,111]. Risk of developing depression has shown to decrease over the course of TB treatment [112] and adherence shown to improve depressive symptoms of patients suffering from MDR-TB [51].

Initial emotional shock and increased mental health toll, along with lack of health education and emotional support during diagnosis and treatment initiation, elevate this period as critical for emotional and educational intervention [41, 103, 108]. In many countries screening and treating psychological challenges among persons diagnosed with TB is limited. This is especially true for alcohol use disorders and its associated impact on prognosis during treatment; people in TB retreatment programmes are more likely to show risky alcohol use patterns [94]. Further, national TB programmes in countries such as South Africa and India primarily frame TB treatment in biomedical terms, focusing on clinical outcomes such as sputum conversion. However, patients may not regard their treatment as successful due to the impact on the disease and treatment episode – this includes a breakdown in social relationship ties, job loss, social exclusion and a loss of identity [102, 113].

Factors influencing relationships between TB and mental illness symptoms

Factors related to gender

The literature identified several important factors that influence relationships between TB and different dimensions of mental illness. Gender is an especially pronounced factor: during diagnostic and treatment phases of TB treatment, women have consistently shown to have significantly poorer mental health outcomes, including general mental health [39], anxiety [47], depression [4, 49, 52, 59, 84], psychological distress [40, 41, 83, 114], suicidality [59] and mental health-related quality of life. However in one exception, men scored higher than women in an outpatient hospital setting in Uttar Pradesh, India [46]. Regarding alcohol use, men are more likely to consume alcohol at harmful levels prior to and during a TB episode [55, 90, 94, 104, 115]. Men also seem less likely to adhere to treatment regimens [116]. Women may cope differently with TB, employing strategies such as positive stress management, planning and seeking emotional support, whereas men use humour and illicit drugs [104]. A Peruvian study suggested younger men have a pronounced need for emotional support and caregiving from their family – likely from mothers and sisters. The study also highlighted partner support was significantly more important for women [103]. Family support has been shown to be important in the prevalence of depression among TB patients [52, 117]. Women are more likely to attempt alcohol cessation and report negative consequences of drinking on personal relationships, and less likely to jeopardise their personal safety due to alcohol use [90].

Factors related to socioeconomic and education background

Patients from lower education backgrounds are more likely to suffer from depressive symptoms [38, 46, 52] and psychological distress [40, 55], and more likely to heavily consume alcohol [94]. Higher education levels on the other hand has been linked to higher mental health-related quality of life [109]. Patients from lower socioeconomic backgrounds are less likely to adhere to treatment [116], more likely to suffer depression [4, 38, 46, 117] and psychological distress [40, 55], and more likely to be heavy alcohol users [94, 115]. HIV/TB coinfection is associated with depressive symptoms [49, 117], while tobacco smoking has also been associated with harmful alcohol use [55] and depression [4] among TB patients. Retreatment, discontinuing treatment [49], and history of TB [41] may make depressive symptoms more likely, while patients who relapse treatment are more likely to be heavy alcohol drinkers [94]. Finally, heavy alcohol use is related to higher levels of depression among TB patients [41], similarly to diabetes [4].

The paucity of person-centred care

The paucity of person-centred perspectives in LMIC and BRICS approaches to address comorbidities between drug-sensitive and drug-resistant TB on the one hand, and mental disorders on the other is clear from the scoping review results. Focusing on person-centred care (as opposed to patient-centred care) and following the required components of patient narrative, collaboration and continuity [21], our search yielded two studies, both in Nepal, that explicitly aimed to develop more person-centred care to address the psychosocial needs of MDR-TB [118, 119].

Some studies have aimed to develop patient-centred models of care, for instance, a South African intervention that trains social workers to support people suffering from drug-resistant TB [120]. In a study in Nicaragua, TB clubs and home visits were implemented to address TB patients’ internalised stigma, with some success [121]. Medecins Sans Frontieres (MSF) developed and implemented a home-based MDR-TB treatment programme in Northern Uganda, which was found to be acceptable to patients, families, communities and healthcare workers [122]. An Ethiopian study investigated the extent to which the directly observed treatment short course (DOTS) strategy is patient-centred, showing that it falls short of achieving such care [123].

Baral and colleagues [118] aimed to explore challenges people face receiving MDR-TB care in Nepal, and to co-develop a person-centred intervention with patients and families. The research underlined the financial and social strains that conventional MDR-TB care places on individuals, including increased expenditure accessing care, and challenges resulting from removal from social networks, stigmatisation, loneliness and medication side effects. An intervention combining psychosocial counselling and added financial support was developed with positive effects on treatment outcomes. Further research from Nepal aimed to develop and test a psychosocial support package to be integrated within routine MDR-TB care [119]. Stakeholder voice was again prioritised, with patient, family member and service provider perspectives elicited, providing understanding of the physical and psychological impact of MDR-TB; the intersection between health facilities, health information and psychological dimensions of disease; patient contact with family and social networks; personal living arrangements; and financial circumstances and livelihood. Developing the intervention collaboratively assisted in strengthening stakeholder capabilities, opportunities and motivations, resulting in more sustained psychological support throughout treatment, especially for patients with limited social support and who faced stigma [119]. While these developments are promising, little to no empirical evidence exists on person-centred care models for drug-sensitive TB programmes, or the impact or effectiveness of person-centred care in improving individual, clinical and programmatic outcomes.

Discussion

This review aimed to explore the nature and extent of comorbidities between TB and mental illness symptoms in LMICs, and to identify and describe person-centred approaches to address such comorbidities. As expected, studies that focused on intersections between TB and mental illness symptoms in LMICs varied considerably according to scope, size, study design and robustness, making comparisons difficult. However, our findings identified four broad tuberculosis and mental disorders comorbidities namely alcohol use and tuberculosis, depression and tuberculosis, anxiety and tuberculosis, and general mental health and tuberculosis. Despite the wide variance between research in different countries, it is clear that experience of a TB disease episode is often accompanied by or related to CMD and alcohol use symptoms (see a summary of main findings in Table 3).

In contrast to research on HIV, there is limited empirical data globally on the prevalence of mental illness symptoms among people suffering from TB [59]. Nonetheless, mental illness rates are higher among people with physical illness compared to the general population, and it might even be higher for people with TB – depression and anxiety certainly seems to be higher [2]. Results from the World Health Survey, conducted among 48 LMICs, suggest comorbid TB and depression significantly worsen health outcomes across all domains, exceeding burdens of TB and depression in isolation. Further, people suffering from TB are almost at a fourfold increased risk of experiencing depressive episodes [4]. Our review demonstrated that a body of evidence is growing in LMICs, rendering an urgent need for standardised concepts and measurements that incorporate person-centred systems of care.

Our findings suggest that initial diagnosis and treatment phases of the TB episode are particularly salient in preventing and treating mental health challenges, as baseline mental illness symptoms negatively affect the treatment phase [38]. Treating mental health challenges is a clinical priority, with psychological distress potentially doubling the risk of non-adherence [41]. Indeed, comorbid mental illness – including substance use – is a major consideration in treatment non-adherence which, in addition to the impact on individuals, has wider public health implications, including significant contributions to transmission and emergence of drug-resistant disease [2].

Research on TB and mental illness comorbidities that stretch beyond describing cross-sectional prevalence rates are rare, with very little attention paid to longitudinal dimensions of the trajectory of comorbidity [3]. Causal pathways between TB and depression are both complex and multidirectional, manifesting in biological, pharmaceutical and psychosocial mechanisms, though the extent to which these pathways contribute to comorbidity burden remains unclear [3, 38]. One mechanism suggests that depression negatively affects self-care in TB treatment, thereby increasing chances of treatment non-adherence and failure [4]. Further, alcohol use before and during treatment has a strong negative effect on a myriad of outcomes, manifested in complex, bidirectional causal chains. Poverty can lead to increased alcohol use, which in turn may lead to an increased likelihood of contracting TB, not being diagnosed in a timely manner, and not adhering to treatment; also, alcohol use may lead to downward social mobility, again creating social conditions favourable for TB disease progression [99]. The review illustrated that there are key nuances in TB and mental illness comorbidity; women are more prone to depression, while men are more likely to engage in harmful alcohol use. Men are also less likely to adhere to treatment regimens. The gendered dimension of comorbidity is an important consideration in TB programme design and again underlines the need for person-centredness. Other vulnerabilities such as poverty, lower levels of education and older age groups present further opportunities for more targeted interventions.

Health system barriers – such as fragmented, non-dependable health information systems, limited patient management, referral and communication fractures between levels of care – further compound challenges during the TB disease episode [124]. These are unfortunately features of many national health systems in LMICs, creating a troubling context for reforms towards person-centredness [125]. Importantly, many challenges faced by TB patients lie outside the formal health system sphere – transport problems, medication reactions and food assistance [126]. A particular silence in current literature relates to occupational dimensions of TB, both prevention and treatment and care. The hidden epidemic of TB among healthcare workers, and the resultant care approaches by employers require urgent attention.

Despite recent growth in person-centred discourse in global health (for instance in the SDGs, Lancet Global Health Commission on High-Quality Health Systems in the SDG Era, WHO Framework for People-centred Health Systems), our review showed that little to no person-centric TB treatment approaches are being deployed in LMICs, with the exception of the two studies in Nepal, which focused on psychosocial support for people suffering from MDR-TB [118, 119]. While there is an increase in attention to patient-centredness in TB care which include patients and their families in decision-making, person-centredness considers the whole person in a wider context rather than a focus on a person’s role as a patient. Very few studies have presented person-centred models of care, as well as comparable empirical investigations into cost effectiveness and programme effectiveness [127]. The person-centred dimensions of patient narrative, collaboration and continuity [21] still fall short in LMIC and BRICS research. Stakeholder voice is especially critical; TB interventions will only be able to achieve positive outcomes with the full inclusion of patients, their families and wider network in the planning and organisation of care [128].

Table 3: Main findings

This review suggested that there is increasing attention being paid to the intersections of mental illness symptoms and TB disease in LMICs. There are well-known vulnerabilities during a TB episode – including those tied to the patient, their family and broader context, as well as persisting health system ills. At the very least, TB programmes should be targeted enough to be able to address key challenges, especially dimensions of gender, education and socioeconomic background. This review highlighted a common feature of international research comparisons, namely the lack of standardisation and fragmentation in the use of different concepts. The study of mental illness and TB crucially requires a globally accepted framework that details the range and nature of comorbidities, as well as robust methods of measurements. Similarly, there is an identified need for a conceptual framework that sets out the definitions of patient -and person-centred care as it applies to TB. This will require wide consensus on the meaning of these terms and how they are operationalised, while inappropriate terms such as ‘TB suspect’ and ‘treatment defaulter’ – with its subtle judgements and disempowerment – should be replaced by person-centred terminology such as ‘people with presumptive TB’ and ‘person lost to follow-up’ [127].

Several concepts used during this review are not clear cut, and its vagueness in interchangeable use renders searching and comparison difficult. Mental illness symptoms are notoriously difficult to pin down, and many nuances go astray during its operationalisation in research. For example, the degree to which alcohol use become a feature of mental illness is not always made entirely clear by researchers, and the distinction between the initial shocks of a TB diagnosis should be differentiated from formally diagnosed anxiety. Similarly, it is possible that some papers might have been missed during the search due to treatment approaches and care not explicitly being named “person-centred”, “patient-centred” or “people-centred”, rather implicitly inferring dimensions of these terms (for instance, “including the patient in decision-making”.

Conclusions

The literature clearly showed that the presentation of mental illness – including substance use, anxiety and depression – during the TB disease trajectory, have a range of negative outcomes. This is often exacerbated in LMICs where the majority of people suffering from TB are often faced with complex challenges such as poverty, gender disparities, limited education and failing health systems. Moreover, mental illness and TB comorbidities were found to be more prevalent within the diagnostic phase and later the treatment stages. These phases were found to be associated with high levels of psychological distress thus often requiring more person-centred TB care models. Addressing psychosocial comorbidities with TB in LMICs and BRICS with person-centred TB care in routine care platforms may yield promising clinical and psychosocial outcomes.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Abbreviations

- ASSET:

-

heAlth System StrEngThening in sub-Saharan Africa

- BRICS:

-

Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa

- CMDs:

-

Common mental disorders

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- LMICs:

-

Low-to-middle income countries

- MDR-TB:

-

Multidrug resistant tuberculosis

- MSF:

-

Médecins Sans Frontieres

- NIHR:

-

National Institute for Health Research

- PCC:

-

Person-centred care

- SDGs:

-

Sustainable Development Goals

- TB:

-

Tuberculosis

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Report 2019. Geneva: WHO; 2019.

Doherty AM, Kelly J, McDonald C, O'Dywer AM, Keane J, Cooney J. A review of the interplay between tuberculosis and mental health. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2013;35(4):398–406.

Ambaw F, Mayston R, Hanlon C, Alem A. Depression among patients with tuberculosis: determinants, course and impact on pathways to care and treatment outcomes in a primary care setting in southern Ethiopia--a study protocol. BMJ Open. 2015;5(7):e007653.

Koyanagi A, Vancampfort D, Carvalho AF, DeVylder JE, Haro JM, Pizzol D, et al. Depression comorbid with tuberculosis and its impact on health status: cross-sectional analysis of community-based data from 48 low- and middle-income countries. BMC Med. 2017;15(1):209.

Munro SA, Lewin SA, Smith HJ, Engel ME, Fretheim A, Volmink J. Patient adherence to tuberculosis treatment: a systematic review of qualitative research. PLoS Med. 2007;4(7):e238.

Creswell J, Raviglione M, Ottmani S, Migliori GB, Uplekar M, Blanc L, et al. Tuberculosis and noncommunicable diseases: neglected links and missed opportunities. Eur Respir J. 2011;37(5):1269–82.

Courtwright A, Turner AN. Tuberculosis and stigmatization: pathways and interventions. Public Health Rep. 2010;125(Suppl 4):34–42.

Janmeja AK, Das SK, Bhargava R, Chavan BS. Psychotherapy improves compliance with tuberculosis treatment. Respiration. 2005;72(4):375–80.

Acha J, Sweetland A, Guerra D, Chalco K, Castillo H, Palacios E. Psychosocial support groups for patients with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis: five years of experience. Global Public Health. 2007;2(4):404–17.

Demissie M, Getahun H, Lindtjorn B. Community tuberculosis care through "TB clubs" in rural North Ethiopia. Soc Sci Med. 2003;56(10):2009–18.

Tola HH, Garmaroudi G, Shojaeizadeh D, Tol A, Yekaninejad MS, Ejeta LT, et al. The effect of psychosocial factors and patients' perception of tuberculosis treatment non-adherence in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2017;27(5):447–58.

Mendenhall E, Kohrt BA, Norris SA, Ndetei D, Prabhakaran D. Non-communicable disease syndemics: poverty, depression, and diabetes among low-income populations. Lancet. 2017;389(10072):951–63.

Sachs JD. From millennium development goals to sustainable development goals. Lancet. 2012;379(9832):2206–11.

ASSET. Health System Strengthening in Sub-Saharan Africa [https://www.healthasset.org/].

Lopez C, Bertram-Farough A, Heywood D, Dawson L, Dillon M, Chochinov HM, et al. Knowing about you: eliciting dimensions of personhood within tuberculosis care. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2017;21(2):149–53.

Li J, Porock D. Resident outcomes of person-centered care in long-term care: a narrative review of interventional research. Int J Nurs Stud. 2014;51(10):1395–415.

Kim SK, Park M. Effectiveness of person-centered care on people with dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Interv Aging. 2017;12:381–97.

Chenoweth L, King MT, Jeon YH, Brodaty H, Stein-Parbury J, Norman R, et al. Caring for aged dementia care resident study (CADRES) of person-centred care, dementia-care mapping, and usual care in dementia: a cluster-randomised trial. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8(4):317–25.

Dwamena F, Holmes-Rovner M, Gaulden CM, Jorgenson S, Sadigh G, Sikorskii A, et al. Interventions for providers to promote a patient-centred approach in clinical consultations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;12:CD003267.

Olsson LE, Jakobsson Ung E, Swedberg K, Ekman I. Efficacy of person-centred care as an intervention in controlled trials–a systematic review. J Clin Nurs. 2013;22(3–4):456–65.

Munthe C, Sandman L, Cutas D. Person centred care and shared decision making: implications for ethics, public health and research. Health Care Anal. 2012;20(3):231–49.

Ekman I, Swedberg K, Taft C, Lindseth A, Norberg A, Brink E, et al. Person-centered care--ready for prime time. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2011;10(4):248–51.

de Silva D. Helping measure person-centred care. London: The Health Foundation; 2014.

Louw JM, Marcus TS, Hugo JFM. Patient- or person-centred practice in medicine? – a review of concepts. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med. 2017;9(1):e1–7.

Håkansson Eklund J, Holmström IK, Kumlin T, Kaminsky E, Skoglund K, Höglander J, et al. “Same same or different?” a review of reviews of person-centered and patient-centered care. Patient Educ Couns. 2019;102(1):3–11.

Lines LM, Lepore M, Wiener JM. Patient-centered, person-centered, and person-directed care: they are not the same. Med Care. 2015;53(7):561–3.

Starfield B. Is patient-centered care the same as person-focused care? Perm J. 2011;15(2):63–9.

Wilberforce M, Challis D, Davies L, Kelly MP, Roberts C, Loynes N. Person-centredness in the care of older adults: a systematic review of questionnaire-based scales and their measurement properties. BMC Geriatr. 2016;16:63.

Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32.

JBI. Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ Manual: Methodology for JBI Scoping Reviews. In: Adelaide; 2015.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O'Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73.

Analytics C. Endnote X9; 2018.

Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan — a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016;5:210.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535.

QSR. NVivo qualitative data analysis Software. In: QSR International Pty Ltd; 2018.

Aamir S, Aisha. Co-morbid anxiety and depression among pulmonary tuberculosis patients. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2010;20(10):703–4.

Kendall EA, Theron D, Franke MF, van Helden P, Victor TC, Murray MB, Warren RM, Jacobson KR. Alcohol, hospital discharge, and socioeconomic risk factors for default from multidrug resistant tuberculosis treatment in rural South Africa: a retrospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2013;8(12):e83480.

Ugarte-Gil C, Ruiz P, Zamudio C, Canaza L, Otero L, Kruger H, et al. Association of major depressive episode with negative outcomes of tuberculosis treatment. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e69514.

Ahmad N, Javaid A, Syed Sulaiman SA, Basit A, Afridi AK, Jaber AAS, et al. Effects of multidrug resistant tuberculosis treatment on patients’ health related quality of life: results from a follow up study. PLoS One. 2016;11(7):e0159560.

Xu M, Markstrom U, Lyu J, Xu L. Survey on tuberculosis patients in rural areas in China: tracing the role of stigma in psychological distress. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14(10):E1171.

Theron G, Peter J, Zijenah L, Chanda D, Mangu C, Clowes P, et al. Psychological distress and its relationship with non-adherence to TB treatment: a multicentre study. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15:253.

Laprawat S, Peltzer K, Pansila W, Tansakul C. Alcohol use disorder and tuberculosis treatment: a longitudinal mixed method study in Thailand. S Afr J Psychiatry. 2017;23:a1074.

Husain MO, Dearman SP, Chaudhry IB, Rizvi N, Waheed W. The relationship between anxiety, depression and illness perception in tberculosis patients in Pakistan. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2008;4:4.

Singh L, Pardal PK, Prakash J. Psychiatric morbidity in patients of pulmonary tuberculosis-an observational study. Ind Psychiatry J. 2015;24(2):168–71.

Chandrashekar T, Pinto DA, Katte R, Hungund BR, Joshi AV. A study of psychiatric morbidity among patients suffering from pulmonary tuberculosis. Medico-Legal Update. 2012;12(2):26–9.

Srivastava AS, Ramdinee NA, Matah SC, Tripathi MN, Pandit B, Yadav JS. Psychiatric morbidities in patients with pulmonary tuberculosis. Dysphrenia. 2014;5(2):133–7.

Duko B, Gebeyehu A, Ayano G. Prevalence and correlates of depression and anxiety among patients with tuberculosis at WolaitaSodo University Hospital and Sodo Health Center, WolaitaSodo, South Ethiopia, Cross sectional study. BMC Psychiatry. 2015;15:214.

Mohammed S, Nagla S, Morten S, Asma E, Arja A. Illness perceptions and quality of life among tuberculosis patients in Gezira, Sudan. Afr Health Sci. 2015;15(2):385–93.

Kehbila J, Ekabe CJ, Aminde LN, Noubiap JJN, Fon PN, Monekosso GL. Prevalence and correlates of depressive symptoms in adult patients with pulmonary tuberculosis in the southwest region of Cameroon. Infect Dis Poverty. 2016;5(1):51.

Hermosilla S, You P, Aifah A, Abildayev T, Akilzhanova A, Kozhamkulov U, et al. Identifying risk factors associated with smear positivity of pulmonary tuberculosis in Kazakhstan. PLoS One. 2017;12(3):e0172942.

Das M, Isaakidis P, Van den Bergh R, Kumar AM, Nagaraja SB, Valikayath A, et al. HIV, multidrug-resistant TB and depressive symptoms: when three conditions collide. Glob Health Action. 2014;7:24912.

Ambaw F, Mayston R, Hanlon C, Alem A. Burden and presentation of depression among newly diagnosed individuals with TB in primary care settings in Ethiopia. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17(1):57.

Scuffell J, Boccia D, Garcia Velarde F, Leon SR, Raviola G, Lecca L, et al. Mental disorders and drug/alcohol use in patients commencing extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis treatment. Public Health Action. 2017;7(3):237–9.

Vega P, Sweetland A, Acha J, Castillo H, Guerra D, Smith Fawzi MC, et al. Psychiatric issues in the management of patients with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2004;8(6):749–59.

Peltzer K, Naidoo P, Matseke G, Louw J, McHunu G, Tutshana B. Prevalence of psychological distress and associated factors in tuberculosis patients in public primary care clinics in South Africa. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12:89.

Dos Santos AP, Lazzari TK, Silva DR. Health-related quality of life, depression and anxiety in hospitalized patients with tuberculosis. Tuberc Respir Dis. 2017;80(1):69–76.

Galhenage JS, Rupasinghe JP, Abeywardena GS, de Silva AP, Williams SS, Gunasena B. Psychological morbidity and illness perception among patients receiving treatment for tuberculosis in a tertiary care Centre in Sri Lanka. Ceylon Med J. 2016;61(1):37–40.

Ige OM, Lasebikan VO. Prevalence of depression in tuberculosis patients in comparison with non-tuberculosis family contacts visiting the DOTS clinic in a Nigerian tertiary care hospital and its correlation with disease pattern. Ment Health Fam Med. 2011;8(4):235–41.

van den Heuvel L, Chishinga N, Kinyanda E, Weiss H, Patel V, Ayles H, et al. Frequency and correlates of anxiety and mood disorders among TB- and HIV-infected Zambians. AIDS Care. 2013;25(12):1527–35.

Zaridze D, Brennan P, Boreham J, Boroda A, Karpov R, Lazarev A, Konobeevskaya I, Igitov V, Terechova T, Boffetta P et al. Alcohol and cause-specific mortality in Russia: a retrospective case-control study of 48,557 adult deaths. Lancet 2009, 373(9682):2201–2214.

Augusto CJ, Carvalho Wda S, Goncalves AD, Ceccato M, Miranda SS. Characteristics of tuberculosis in the state of Minas Gerais, Brazil: 2002–2009. Jornal brasileiro de pneumologia : publicacao oficial da Sociedade Brasileira de Pneumologia e Tisilogia 2013, 39(3):357–364.

Deponti GN, Silva DR, Coelho AC, Muller AM, Dalcin Pde T. Delayed diagnosis and associated factors among new pulmonary tuberculosis patients diagnosed at the emergency department of a tertiary care hospital in Porto Alegre, South Brazil: a prospective patient recruitment study. BMC Infect Dis 2013, 13:538.

Hermosilla S, You P, Aifah A, Abildayev T, Akilzhanova A, Kozhamkulov U, Muminov T, Darisheva M, Zhussupov B, Terlikbayeva A et al. Identifying risk factors associated with smear positivity of pulmonary tuberculosis in Kazakhstan. PLoS One 2017, 12(3):e0172942.

Jankowska-Polanska BK, Kaminska M, Uchmanowicz I, Rycombel A. Quality of life and health behaviours of patients with tuberculosis - sex differences. Pneumonologia i alergologia polska 2015, 83(4):256–265.

Lackey B, Seas C, Van der Stuyft P, Otero L. Patient characteristics associated with tuberculosis treatment default: a cohort study in a high-incidence area of Lima, Peru. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0128541.

Louw JS, Mabaso M, Peltzer K. Change in Health-Related Quality of Life among Pulmonary Tuberculosis Patients at Primary Health Care Settings in South Africa: A Prospective Cohort Study. PLoS One 2016, 11(5):e0151892.

Louw J, Peltzer K, Naidoo P, Matseke G, McHunu G, Tutshana B. Quality of life among tuberculosis (TB), TB retreatment and/or TB-HIV co-infected primary public health care patients in three districts in South Africa. Health & Quality of Life Outcomes 2012, 10(1):77–84.

Meda ZC, Huang CC, Sombie I, Konate L, Somda PK, Djibougou AD, Sanou M. Tuberculosis in developing countries: conditions for successful use of a decentralized approach in a rural health district. The Pan African medical journal 2014, 17:198.

Miller AC, Gelmanova IY, Keshavjee S, Atwood S, Yanova G, Mishustin S, et al. Alcohol use and the management of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in Tomsk, Russian Federation. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2012;16(7):891–6.

O'Connell R, Chishinga N, Kinyanda E, Patel V, Ayles H, Weiss HA, et al. Prevalence and correlates of alcohol dependence disorder among TB and HIV infected patients in Zambia. PLoS One. 2013;8(9):e74406.

Thapa P, Kamath R, Shetty BK, Monteiro A, Sekaran VC. Prevalence and Associated Factors of Alcoholism among Tuberculosis Patients in Udupi Taluk, Karnataka, India: A Cross Sectional Study. Journal of Nepal Health Research Council 2014, 12(28):177–181.

Naidoo P, Peltzer K, Louw J, Matseke G, McHunu G, Tutshana B. Predictors of tuberculosis (TB) and antiretroviral (ARV) medication non-adherence in public primary care patients in South Africa: a cross sectional study. BMC Public Health 2013, 13:396.

Peltzer K, Louw JS. Prevalence and factors associated with tuberculosis treatment outcome among hazardous or harmful alcohol users in public primary health care in South Africa. African health sciences 2014, 14(1):157–166.

Peltzer K, Louw J. Prevalence of suicidal behaviour & associated factors among tuberculosis patients in public primary care in South Africa. The Indian journal of medical research 2013, 138:194–200.

Peltzer K, Louw J, McHunu G, Naidoo P, Matseke G, Tutshana B. Hazardous and harmful alcohol use and associated factors in tuberculosis public primary care patients in South Africa. International journal of environmental research and public health 2012, 9(9):3245–3257.

Bumburidi E, Ajeilat S, Dadu A, Aitmagambetova I, Ershova J, Fagan R, et al. Progress toward tuberculosis control and determinants of treatment outcomes--Kazakhstan, 2000-2002. MMWR Supplements. 2006;55(1):11–5.

Fleming MF, Krupitsky E, Tsoy M, Zvartau E, Brazhenko N, Jakubowiak W, et al. Alcohol and drug use disorders, HIV status and drug resistance in a sample of Russian TB patients. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2006;10(5):565–70.

Krupitsky EM, Zvartau EE, Lioznov DA, Tsoy MV, Egorova VY, Belyaeva TV, et al. Co-morbidity of infectious and addictive diseases in St. Petersburg and the Leningrad region, Russia. Eur Addict Res. 2006;12(1):12–9.

Gelmanova IY, Keshavjee S, Golubchikova VT, Berezina VI, Strelis AK, Yanova GV, et al. Barriers to successful tuberculosis treatment in Tomsk, Russian Federation: non-adherence, default and the acquisition of multidrug resistance. Bull World Health Organ. 2007;85(9):703–11.

Jakubowiak WM, Bogorodskaya EM, Borisov SE, Danilova ID, Kourbatova EV. Risk factors associated with default among new pulmonary TB patients and social support in six Russian regions. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2007;11(1):46–53.

Kliiman K, Altraja A. Predictors and mortality associated with treatment default in pulmonary tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2010;14(4):454–63.

Duarte EC, Bierrenbach AL, Barbosa da Silva J Jr, Tauil PL, de Fatima Duarte E. Factors associated with deaths among pulmonary tuberculosis patients: a case-control study with secondary data. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2009;63(3):233–8.

Paulo BX, Peixoto B. Emotional distress patients with several types of tuberculosis. A pilot study with patients from the Sanatorium Hospital of Huambo. Int J Mycobacteriol. 2016;5(Suppl 1):S58.

Xavier PB, Peixoto B. Emotional distress in Angolan patients with several types of tuberculosis. Afr Health Sci. 2015;15(2):378–84.

de Araújo GS, Pereira SM, dos Santos DN, Marinho JM, Rodrigues LC, Barreto ML. Common mental disorders associated with tuberculosis: a matched case-control study. PLoS One. 2014;9(6):e99551.

Ndishimye P, Domokos B, Stillo J, Seghrouchni F, Mrabet O, Homorodean D, et al. A case control study of risk factors associated with pulmonary tuberculosis in Romania: experience at a clinical hospital of pneumology. Clujul Med. 2017;90(1):54–9.

van den Hof S, Tursynbayeva A, Abildaev T, Adenov M, Pak S, Bekembayeva G, et al. Converging risk factors but no association between HIV infection and multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in Kazakhstan. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2013;17(4):526–31.

Vijay S, Kumar P, Chauhan LS, Vollepore BH, Kizhakkethil UP, Rao SG. Risk factors associated with default among new smear positive tb patients treated under DOTS in India. PLoS One. 2010;5(4):e10043.

Priedeman Skiles M, Curtis SL, Angeles G, Mullen S, Senik T. Evaluating the impact of social support services on tuberculosis treatment default in Ukraine. PLoS One. 2018;13(8):e0199513.

Shin SS, Mathew TA, Yanova GV, Fitzmaurice GM, Livchits V, Yanov SA, et al. Alcohol consumption among men and women with tuberculosis in Tomsk, Russia. Cent Eur J Public Health. 2010;18(3):132–8.

Patel K, Patel K, Patel D, Patel P, Patel S, Bansal RJCM. Factors associated with treatment defaulter among tuberculosis patients registered under RNTCP in Surat City. Gujarat. 2016;7(9):763–7.

Finlay A, Lancaster J, Holtz TH, Weyer K, Miranda A, van der Walt M. Patient- and provider-level risk factors associated with default from tuberculosis treatment, South Africa, 2002: a case-control study. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:56.

Salles CL, Conde MB, Hofer C, Cunha AJ, Calcada AL, Menezes DF, Sa L, Kritski AL. Defaulting from anti-tuberculosis treatment in a teaching hospital in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2004;8(3):318–22.

Suhadev M, Thomas BE, Raja Sakthivel M, Murugesan P, Chandrasekaran V, Charles N, et al. Alcohol use disorders (AUD) among tuberculosis patients: a study from Chennai, South India. PLoS One. 2011;6(5):e19485.

Kolappan C, Gopi PG, Subramani R, Narayanan PR. Selected biological and behavioural risk factors associated with pulmonary tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2007;11(9):999–1003.

Santha T, Garg R, Frieden TR, Chandrasekaran V, Subramani R, Gopi PG, et al. Risk factors associated with default, failure and death among tuberculosis patients treated in a DOTS programme in Tiruvallur District, South India, 2000. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2002;6(9):780–8.

Roy N, Basu M, Das S, Mandal A, Dutt D, Dasgupta S. Risk factors associated with default among tuberculosis patients in Darjeeling district of West Bengal, India. J Family Med Prim Care. 2015;4(3):388–94.

Imtiaz S, Shield KD, Roerecke M, Samokhvalov AV, Lönnroth K, Rehm J. Alcohol consumption as a risk factor for tuberculosis: meta-analyses and burden of disease. Eur Respir J. 2017;50(1):1700216.

Rehm J, Samokhvalov AV, Neuman MG, Room R, Parry C, Lönnroth K, et al. The association between alcohol use, alcohol use disorders and tuberculosis (TB). A systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:450.

Jaiswal A, Singh V, Ogden JA, Porter JD, Sharma PP, Sarin R, Arora VK, Jain RC. Adherence to tuberculosis treatment: lessons from the urban setting of Delhi, India. Tropical Med Int Health. 2003;8(7):625–33.

Balgude A, Sontakke S. Study of impact of antitubercular therapy on quality of life. Indian J Med Sci. 2012;66(3–4):71–7.

Sharma R, Yadav R, Sharma M, Saini V, Koushal V. Quality of life of multi drug resistant tuberculosis patients: a study of North India. Acta Med Iran. 2014;52(6):448–53.

Paz-Soldan VA, Alban RE, Jones CD, Oberhelman RA. The provision of and need for social support among adult and pediatric patients with tuberculosis in Lima, Peru: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:290.

Jankowska-Polanska BK, Kamińska M, Uchmanowicz I, Rycombel A. Quality of life and health behaviours of patients with tuberculosis—sex differences. Pneumonol Alergol Pol. 2015;83(4):256–65.

Venkatraju B, Prasad S. Psychosocial trauma of diagnosis: a qualitative study on rural TB patients' experiences in Nalgonda district, Andhra Pradesh. Indian J Tuberc. 2013;60(3):162–7.

Méda ZC, Somé T, Sombié I, Maré D, Morisky DE, Chen YM. Patients infected by tuberculosis and human immunodeficiency virus facing their disease, their reactions to disease diagnosis and its implication about their families and communities, in Burkina Faso: a mixed focus group and cross sectional study. BMC Res Notes. 2016;9:373.

Zhang SR, Yan H, Zhang JJ, Zhang TH, Li XH, Zhang YP. The experience of college students with pulmonary tuberculosis in Shaanxi, China: a qualitative study. BMC Infect Dis. 2010;10(1):174.

Thomas BE, Shanmugam P, Malaisamy M, Ovung S, Suresh C, Subbaraman R, et al. Psycho-socio-economic issues challenging multidrug resistant tuberculosis patients: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2016;11(1):e0147397.

Louw JS, Mabaso M, Peltzer K. Change in health-related quality of life among pulmonary tuberculosis patients at primary health care settings in South Africa: a prospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2016;11(5):e0151892.

Kastien-Hilka T, Rosenkranz B, Bennett B, Sinanovic E, Schwenkglenks M. How to evaluate health-related quality of life and its association with medication adherence in pulmonary tuberculosis - designing a prospective observational study in South Africa. Front Pharmacol. 2016;7:125.

Babikako HM, Neuhauser D, Katamba A, Mupere E. Feasibility, reliability and validity of health-related quality of life questionnaire among adult pulmonary tuberculosis patients in urban Uganda: cross-sectional study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2010;8:93.

Atif M, Sulaiman SA, Shafie AA, Asif M, Sarfraz MK, Low HC, et al. Impact of tuberculosis treatment on health-related quality of life of pulmonary tuberculosis patients: a follow-up study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2014;12:19.

Walker TM, Cruz ALG, Peto TE, Smith EG, Esmail H, Crook DW. Tuberculosis is changing. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17(4):359–61.

Feng D, Xu L. The relationship between perceived discrimination and psychological distress among Chinese pulmonary tuberculosis patients: the moderating role of self-esteem. Psychol Health Med. 2015;20(2):177–85.

Thapa P, Kamath R, Shetty BK, Monteiro A, Sekaran VC. Prevalence and associated factors of alcoholism among tuberculosis patients in Udupi Taluk, Karnataka, India: a cross sectional study. J Nepal Health Res Counc. 2014;12(28):177–81.

Naidoo A, Naidoo SS, Gathiram P, Lalloo UG. Tuberculosis in medical doctors - a study of personal experiences and attitudes. S Afr Med J. 2013;103(3):176–80.

Andersson LM, Schierenbeck I, Strumpher J, Krantz G, Topper K, Backman G, et al. Help-seeking behaviour, barriers to care and experiences of care among persons with depression in eastern cape, South Africa. J Affect Disord. 2013;151(2):439–48.

Baral SC, Aryal Y, Bhattrai R, King R, Newell JN. The importance of providing counselling and financial support to patients receiving treatment for multi-drug resistant TB: mixed method qualitative and pilot intervention studies. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:46.

Khanal S, Elsey H, King R, Baral SC, Bhatta BR, Newell JN. Development of a patient-centred, psychosocial support intervention for multi-drug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) care in Nepal. PLoS One. 2017;12(1):e0167559.

Zelnick JR, Seepamore B, Daftary A, Amico KR, Bhengu X, Friedland G, et al. Training social workers to enhance patient-centered care for drug-resistant TB-HIV in South Africa. Public Health Action. 2018;8(1):25–7.

Macq J, Solis A, Martinez G, Martiny P. Tackling tuberculosis patients' internalized social stigma through patient centred care: an intervention study in rural Nicaragua. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:154.

Horter S, Stringer B, Reynolds L, Shoaib M, Kasozi S, Casas EC, et al. "Home is where the patient is": a qualitative analysis of a patient-centred model of care for multi-drug resistant tuberculosis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:81.

Getahun B, Nkosi ZZ. Is directly observed tuberculosis treatment strategy patient-centered? A mixed method study in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2017;12(8):e0181205.

Dudley L, Mukinda F, Dyers R, Marais F, Sissolak D. Mind the gap! Risk factors for poor continuity of care of TB patients discharged from a hospital in the Western cape, South Africa. PLoS One. 2018;13(1):e0190258.

Loveday M, Padayatchi N, Voce A, Brust J, Wallengren K. The treatment journey of a patient with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in South Africa: is it patient-centred? Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2013;17(10 Suppl 1):56–9.

Tupasi T, Garfin AM, Mangan JM, Orillaza-Chi R, Naval LC, Balane GI, et al. Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis patients' views of interventions to reduce treatment loss to follow-up. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2017;21(1):23–31.

Odone A, Roberts B, Dara M, van den Boom M, Kluge H, McKee M. People- and patient-centred care for tuberculosis: models of care for tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2018;22(2):133–8.

Macq J, Torfoss T, Getahun H. Patient empowerment in tuberculosis control: reflecting on past documented experiences. Tropical Med Int Health. 2007;12(7):873–85.

Peltzer K, Naidoo P, Matseke G, Louw J, McHunu G, Tutshana B. Prevalence of post-traumatic stress symptoms and associated factors in tuberculosis (TB), TB retreatment and/or TB-HIV co-infected primary public health-care patients in three districts in South Africa. Psychol Health Med. 2013;18(4):387–97.

Peltzer K, Louw JS. Prevalence and factors associated with tuberculosis treatment outcome among hazardous or harmful alcohol users in public primary health care in South Africa. Afr Health Sci. 2014;14(1):157–66.

Chishinga N, Kinyanda E, Weiss HA, Patel V, Ayles H, Seedat S. Validation of brief screening tools for depressive and alcohol use disorders among TB and HIV patients in primary care in Zambia. BMC Psychiatry. 2011;11:75.

Walker IF, Baral SC, Wei X, Huque R, Khan A, Walley J, et al. Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis treatment programmes insufficiently consider comorbid mental disorders. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2017;21(6):603–9.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Ruwayda Petrus and Dr. Roisin Drysdale for valuable mentoring during the scoping review process.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Global Health Research Unit on Health System Strengthening in Sub-Saharan Africa, King’s College London (GHRU 16/136/54) using UK aid from the UK Government to support global health research. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AvR led the writing of the protocol, was involved in screening for all levels, extraction, synthesis, wrote the first drafts of the manuscript and was the project coordinator. AD was involved in protocol writing, screening for all levels, extraction, synthesis and editing the manuscript. RC, FA, JM and MB contributed to data synthesis and the formulation of conclusions. IP and LF contributed to study design, aim and objectives, data synthesis and formulation of conclusions. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

AvR and IP: Centre for Rural Health, School of Nursing and Public Health, University of KwaZulu-Natal Howard Campus, Berea, Durban, South Africa; AD, RC, LF: Knowledge Translation Unit, University of Cape Town Lung Institute, George Street, Mowbray, Cape Town, South Africa; FA: College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Bahir Dar University, Bahir Dar, Ethiopia; JM and MB: University of East Anglia School of Health Sciences, Norwich Research Park, Norwich, Norfolk, United Kingdom. Authors part of NIHR Health System Strengthening in Sub-Saharan Africa consortium (https://www.healthasset.org/).

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Janse Van Rensburg, A., Dube, A., Curran, R. et al. Comorbidities between tuberculosis and common mental disorders: a scoping review of epidemiological patterns and person-centred care interventions from low-to-middle income and BRICS countries. Infect Dis Poverty 9, 4 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40249-019-0619-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40249-019-0619-4