Abstract

Despite the relevance of drought stress, the regulation of gene expression, protein accumulation, and plant physiology under water-deficit stress is not well understood in Korean F1 maize (Zea mays L.) hybrids. In this study, we investigated the effect of water deficit on the F1 maize hybrids, Ilmichal (Ilmi) and Gwangpyeongok (GPOK), by withholding water for 10 days during flowering. Water deficit severely reduced the relative water content, area, SPAD values, and stomatal conductance of leaves, stem length, and the dry matter content of aerial tissues in drought-stressed plants of both hybrids. However, the dry matter content of roots was reduced only in GPOK. Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis identified 24 spots representing proteins accumulated to differential levels in well-watered and drought-stressed plants of both hybrids. Further analysis of protein spots using matrix assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight mass spectrometry and protein database searches revealed that nine proteins were involved in carbohydrate metabolism, seven in stress response, and two in photosynthesis. Among these proteins, delta 3,5-delta 2,4-dienoyl-CoA isomerase (spot 8) and bifunctional 3-phosphoadenosine 5-phosphosulfate synthetase 2 (spot 23) were present only in GPOK, whereas NAD-dependent epimerase/dehydratase (spot 13), NAD(P)H-quinone oxidoreductase subunit 2 A (spot 24), and an uncharacterized protein (spot 19) were present only in Ilmi, in response to water-deficit stress. Semi-quantitative reverse transcription PCR analysis showed that the transcript levels of most of the genes encoding these proteins correlated well with their protein levels, suggesting that water deficit affects gene transcription in F1 maize hybrids at the flowering stage.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The important environmental factor that limits the growth and productivity of plants is water availability [1]. Global warming is increasing the risk of severe drought stress [2]. The perceived need to gain further understanding of the molecular and biochemical modulations in crops has raised the focus on water stress physiology [3, 4]. Water deficit affects the level of amino acids, amines, sugars, and sugar alcohols in various plant species [5] and reduces vegetative growth, stomatal closure, and photosynthetic rate [6, 7].

Maize (Zea mays L.) serves as a staple food crop and is also used for applications of industry and production of bio-energy [8]. Maize is adapted to a broad range of environments; however, it is the most productive under optimal environmental conditions and is highly vulnerable to diverse stresses, containing water deficit [9]. Water-deficit stress not only inhibits the development and growth of maize plants during the early growth stages but also has a considerable effect on architecture, kernel number, ear size, and maize growth at the reproductive stage [10, 11]. Many studies show that water deficit reduces the photosynthetic activity of maize plants [12, 13]. One of the earliest responses to water deficit is stomatal closure, as it reduces water loss due to transpiration; however, stomatal closure also decreases CO2 absorption, which reduces photosynthetic activity [14].

Water-deficit stress causes several differences in plants at the molecular level. Recently, large-scale plant proteomic investigation has been conducted to study the molecular changes in maize in response to water deficit [15, 16] and to compare the molecular changes in drought-sensitive and -tolerant maize genotypes [16, 17]. These analyses enable the finding of proteins that are directly responsible for drought tolerance. Transcriptomic analyses have also been used to study the large-scale dehydration modulated gene expression in leaf meristem and reproductive tissues [18] and seedling shoots [19] of maize genotypes.

Changes in transcript and protein levels have been investigated in a lot of maize cultivars under various conditions, encompassing drought stress, and abscisic acid (ABA) treatment. Nevertheless, the effect of water deficit on maize cultivars developed by the Rural Development Administration (RDA) in Korea has not been studied to date. In this investigation, we aimed to examine the changes of physiology and protein in Korean F1 maize hybrids, Ilmichal (Ilmi) and Gwangpyeongok (GPOK), subjected to water-deficit stress. Watering of these F1 maize hybrid plants was withheld for 10 days, and global protein levels were evaluated using two-dimensional gel electrophoresis (2-DE) combined with MALDI–TOF MS. Gene expression levels were also analyzed using semi-quantitative RT-PCR to discover the correlation between transcript and protein levels.

Materials and methods

Plant material and growth conditions

Korean F1 maize hybrids, GPOK (normal type) and Ilmi (waxy type), popular in South Korea, were used in this study. Three seeds of each hybrid were planted in plastic 14.7 L cylindrical pots (25 cm wide × 30 cm tall) filled in sandy loam soil on April 29, 2014. Maize was grown in the greenhouse (Suwon, South Korea). At the flowering stage of tassel emergence, water supply was stopped to impose drought stress on the plants, and leaf visible wilting occurred at 2 or 3 days after withholding water when content of soil moisture was around 10% (v/v). After visible wilting, water supply was withheld for 10 days. Content of volumetric soil moisture was quantified using a capacitance-type sensor (SM100, Spectrum Technologies, Inc., USA). Control plants were drip-irrigated for 1 h a day using an automatic irrigation system (Netafim Ltd., Israel) to reach a soil water content of 20% (v/v). Plants were fertilized with 72.5, 30, and 60 kg ha−1 N, P2O5, and K2O, respectively.

Relative leaf water content

The youngest fully extended leaf was harvested from maize at 10 days after withholding water. The leaves were weighed to measure the fresh weight. Then, the leaves were floated on water for up to 48 h and weighed to determine the turgid weight. Subsequently, the leaves were sliced into small segment and oven-dried at approximately 70 °C to determine the dry weight for 5 days. The relative water content (RWC) of leaves was calculated according to the following equation [20]:

Measurement of chlorophyll content, leaf stomatal conductance and photosynthetic rate

The chlorophyll content of the flag leaf was measured using a portable chlorophyll meter (Konica Minolta SPAD 502 Plus Chlorophyll Meter, Spectrum Technologies, Inc., IL, USA). And leaf stomatal conductance and net photosynthetic rate were measured on the flag leaf using a portable gas exchange system (Li 6400, LI COR, Lincoln, NB, USA) at 10 days after withholding water. All other variables within the leaf chamber of the Li 6400 were standardized during measurements; leaf temperature was maintained at 25 °C and photosynthetic photon flux density (PPFD) at 1500 µmol quanta m−2 s−1 [21]. All measurements were replicated 3 times for each three plants of well-watered and drought-stressed, respectively.

Protein extraction

Proteins were extracted from maize leaf as reported previously [22]. Briefly, fresh leaves of maize F1 hybrids, Ilmi and GPOK (three independent samples), were ground to a fine powder in liquid nitrogen using a pestle and homogenized in 5 mL of Mg/NP-40 buffer including 0.5 M Tris–HCl (pH 8.3) and 2% β-mercaptoethanol. And then samples were centrifuged at 12,000×g for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was blended with a same volume of Tris-saturated phenol (pH 7.5), followed by centrifugation at 12,000×g for 10 min at 4 °C. The phenol phase was mingled with four volumes of methanol which was containing 0.1 M ammonium acetate and precipitated at − 20 °C for 1 h. The samples were then centrifuged at 12,000×g for 10 min at 4 °C. The pellets were rinsed three times with 5 mL of ice-cold acetone, as delineated previously [22], and stored in 80% acetone at − 20 °C until needed for protein quantification.

Analysis of 2-D gel images

The 2-D gel images were analyzed as depicted previously [22]. The protein pellets were melted in rehydration solution (GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI, USA). The immobilized pH gradient (IPG) strips (24 cm) were rehydrated in rehydration solution including equal amounts (250 μg) of protein samples. Subsequently, IPG focusing was performed using the IPGphor II platform (GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI, USA) according to the following protocol: 50 V for 4 h, 100 V for 1 h, 500 V for 1 h, 1000 V for 1 h, 2000 V for 1 h, 4000 V for 2 h, 8000 V for 14 h, and 60 V for 6 h. Each focused IPG strip was equilibrated as described previously [22]. The analysis of 2-DE was carried out using 13% SDS–polyacrylamide gels, which were then dyed with colloidal Coomassie Brilliant Blue (CBB). There biologically replicates for 2-DE were carried out to collect data. Gel images were obtained through a scanner (PowerLook 1120, UMAX) with a 32 bit pixel depth, 300 dpi resolution, and default settings for brightness and contrast. Protein spots were automatically quantified by the ImageMaster 2D Platinum software 6.0 (GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI, USA). The size of each spot was then normalized to the average size of protein spots from three biological replicate gels.

In-gel digestion

Spots showing differential accumulation of proteins in well-watered and water deficit maize hybrids were digested with trypsin [22]. The CBB-stained protein spots were cut out from the 2-D gels with a razor blade, cleaned with 0.1 M ammonium bicarbonate (NH4HCO3) including 50% (v/v) acetonitrile (ACN), and vacuum-dried. The gel pieces were then applied with 0.1 M NH4HCO3 including 10 mM DTT in at 55 °C for 45 min. The DTT solution was immediately replaced with 55 mM iodoacetamide in 0.1 M NH4HCO3, and samples were kept in the dark at room temperature for 30 min. Gel pieces were then cleaned with 0.1 M NH4HCO3 containing 50% ACN, and the protein in these gel pieces was digested with 12.4 ng μL−1 trypsin (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) at 37 °C overnight in 10 μL of digestion solution containing 25 mM NH4HCO3. The digested peptide samples were subsequently air-dried.

MALDI–TOF MS analysis

The matrix solution for MALDI–TOF MS was arranged by melting α-Cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (α-CCA; Sigma-Aldrich) and nitrocellulose in acetone to final concentrations of 40 mg mL−1 and 20 mg mL−1, respectively [23]. The isopropanol, the nitrocellulose, and α-CCA solution were blended in a ratio of 50:50:100, and 2 μL of this composite was added to an equal volume (2 μL) of the peptide sample solution. One microliter of this peptide solution was immediately dropped on a MALDI plate and incubated at room temperature for 5 min. The plate was rinsed with 0.1% (v/v) TFA. The peptide spots were evaluated by a Voyager-DE STR MALDI–TOF mass spectrometer (PerSeptive Biosystems, Framingham, MA, USA). Parent ion masses were examined in the reflection/delayed extraction mode at 20 kV accelerating voltage, 76.000% grid voltage, 0.010% guide wire voltage, and 150 ns delay. Two-point internal standards for calibration were Des-Arg1-bradykinin (m/z = 904.4681) and angiotensin 1 (m/z = 1296.6853). Peptides with a molecular mass ranging from 500 to 3000 Da were selected and analyzed using the PerSeptive-Grams software package. Database searches were achieved using Mascot (http://www.matrixscience.com) and Protein Prospector (http://prospector.ucsf.edu) for protein identification.

Semi-quantitative RT-PCR

PCRs were carried out as documented previously [23]. Primers were designed to amplify 200–300 bp fragments. The maize tubulin gene was employed to normalize the cDNA concentration for each sample. PCR were conducted using gene-specific primers (Additional file 1: Table S1) and were separated on a 1% agarose gel by electrophoresis. The RT-PCR procedures were replicated at least twice.

Statistical analysis

All data were represented as mean ± standard error of mean (SEM) and inquired using SAS statistical software package ver. 9.2 (SAS Institute, USA). Statistically significant differences among treatment means within a maize F1 hybrid were determined using Duncan’s multiple range test (α = 0.05) in SAS. Analyses of simple correlation and regression, and Probit analysis to evaluate the consequence of consecutive days of visible wilting on maize yield, were performed using SAS. Grain yield components and maize yield were arranged using Sigma Plot ver. 10.0 (Systat Software, Inc., USA). Statistical analyses of protein spots were performed using the analysis of variance (ANOVA) to determine statistically different values at a significance of p ≤ 0.05.

Results and discussion

The water deficit at the flowering stage for 10 day severely reduced the RWC of leaves of both Ilmi and GPOK plants (Fig. 1a). This water deficit induced the senescence of lower leaves in drought-stressed plants of both Ilmi and GPOK, thus reducing the leaf number to approximately three and six, respectively, whereas the leaf number in well-watered (control) plants was unaffected (Fig. 1b). This reduction in the leaf number of drought-stressed Ilmi and GPOK plants led to a reduction in the leaf area by approximately 36% and 45%, respectively (Fig. 1c). Our results are coincident with those of several previous researches [24,25,26,27], suggesting that water deficit during reproductive growth accelerates leaf senescence.

Effect of water deficit on the physiology of Korean F1 maize hybrids, Ilmichal (Ilmi) and Gwangpyeongok (GPOK). a Relative water content of leaves and b leaf area of well-watered (control) and drought-stressed plants are shown. Water supply was withheld for 10 days during flowering. Data represent mean ± standard error of mean (n = 3)

Water-deficit stress also reduced the stem length by approximately 16% and 20% in Ilmi and GPOK, respectively (Additional file 2: Figure S1A), which is in agreement with the results of previous researches [26, 28]. The ear length was reduced by approximately 40% in drought-stressed plants (Additional file 2: Figure S1B); however, no significant reduction in the tassel length was observed due to water-deficit stress (data not shown). These results indicate that the 10 day water deficit during tassel emergence has a severe effect on ear growth, possibly because drought stress was imposed when the ear was at the initiation of a rapid elongation phase and was only 40–50% of its final extent [29].

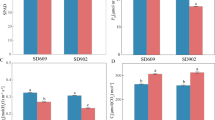

We also measured the SPAD value, leaf stomatal conductance, and photosynthetic rate of the flag leaf (Fig. 2). SPAD values of drought-stressed Ilmi and GPOK plants were reduced by approximately 53% and 64%, respectively, compared with those of control plants (Fig. 2a). Saglam et al. [30] previously reported similar results in maize plants subjected to a 30 day water deficiency during grain filling; these plants showed 3.5-fold reduction in total chlorophyll content parallelized with well-watered plants. In this study, the 10 day water deficit reduced leaf stomatal conductance by approximately 98% in Ilmi and 96% in GPOK compared with the control (Fig. 2b). Photosynthesis is impaired by water deficit because of stomatal closure and other non-stomatal factors, leading to diminish in photosynthetic activity (Fig. 2c) [13]. One of the earliest plant responses to water deficit is stomatal closure, thus reducing transpiration, CO2 uptake, and photosynthetic activity [30]. These results indicate that leaf stomatal closure was responsible for the reduction in photosynthesis in drought-stressed plants of Ilmi and GPOK.

Effect of water deficit on the chlorophyll content and photosynthetic activity of Korean F1 maize hybrids, Ilmichal (Ilmi) and Gwangpyeongok (GPOK). SPAD value (a), leaf stomatal conductance (b), and photosynthetic rate (c) of well-watered (control) and drought-stressed plants of Ilmi and GPOK are shown. Water supply was withheld for 10 days during flowering. Data represent mean ± standard error of mean (n = 3)

The 10 day water deficit during tassel emergence reduced the dry matter accumulation in leaves and stems of both hybrids (Fig. 3); however, this effect was more severe in GPOK than in Ilmi, as the total dry matter content of aerial tissues of drought-stressed plants was reduced by approximately 50% in GPOK and 38% in Ilmi (Fig. 3a). Previously, Denmead and Shaw [28] reported a 40% and 9% reduction in the total dry matter content of aerial tissues of maize plants due to water-deficit stress during tassel emergence. In this study, the 10 day water deficit reduced the dry matter content of roots by approximately 25% only in GPOK; the dry matter content of Ilmi roots was unaffected (Fig. 3b). These results imply that GPOK is more sensitive to water deficit than Ilmi during tassel emergence, which is coincident with a previous study [26].

Effect of water deficit on dry matter accumulation in Korean F1 maize hybrids, Ilmichal (Ilmi) and Gwangpyeongok (GPOK). The dry matter content of aerial tissues (a) and roots (b) of well-watered and drought-stressed Ilmi and GPOK plants is shown. Water supply was withheld for 10 days during flowering. Data represent mean ± standard error of mean (n = 3)

To further understand the fundamental mechanisms for the differential response of Korean F1 maize hybrids to water-deficit stress, we extracted proteins from control and drought-stressed leaves of Ilmi and GPOK using phenol. IPG strips (neutral, pH 5–8) were used for isoelectric separation of proteins to accomplish optimal resolution in 2-D gels. The 2-DE analyses were performed in triplicate, and gels were dyed with CBB. A distinction of gels from control and water deficit leaves using ImageMaster software identified 24 protein spots (Fig. 4). Of these, 12 protein spots (2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 9, 10, 14, 15, 17, 20, and 22) were markedly larger and 7 spots (1, 7, 11, 12, 16, 18, and 21) were smaller in drought-stressed samples of both Ilmi and GPOK than in the control (Fig. 4; Table 1). These results showed that water deficit affected the several abundant proteins in Ilmi and GPOK leaves at the flowering stage; however, the some of the affected proteins was differentially regulated between both F1 hybrids under drought stress.

2-DE of proteins extracted from leaves of Korean F1 maize hybrids, Ilmichal (Ilmi) and Gwangpyeongok (GPOK). Representative images of 2-D gels are shown for well-watered (control) samples (a, b) and drought-stressed samples (c, d) of Ilmi and GPOK. Water supply was withheld for 10 days during flowering. Spots showing differentially accumulated proteins are indicated with arrows

Proteins in these spots were subjected to MALDI–TOF procedure and identified via protein searches using Protein Prospector and Mascot databases. Only the proteins in spots 8 and 23 in GPOK and spots 13, 19, and 24 in Ilmi were identified. These proteins were arranged according to the functional categories established previously [23]. Results showed that these proteins comprised 11 metabolism-related proteins, 7 defense/stress-related proteins, 2 photosynthesis-related proteins, 1 protein involved in protein synthesis, and 3 unknown function proteins (Table 1).

Major enzymes related to carbohydrate metabolism responded to water deficit in the leaves of Ilmi and GPOK plants. The abundance of malate dehydrogenase (MDH; spot 9), two isoforms of NAD-dependent epimerase/dehydratase (spots 13 and 14), alpha-galactosidase (AGA; spot 20), and isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH; spot 22) was increased, whereas that of triosephosphate isomerase (TPI; spot 11), carbonic anhydrase (CA; spot 16), fructose-bisphosphate aldolase (FBA; spot 18), and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GA3PD; spot 21) was reduced, under water-deficit surroundings in both F1 hybrids. Among the proteins whose levels enlarged in response to water deficit, MDH is involved in carbohydrate synthesis, NAD-dependent epimerase/dehydratase make use of NAD as a cofactor and nucleotide-sugar as substrates for various chemical reactions, and AGA and IDH are key enzymes in the raffinose metabolic pathway and tricarboxylic acid cycle, respectively. Of these proteins, the expression of MDH was up-regulated by drought stress in wild watermelon and grapevine [31]. IDH activity showed a gradual increase during drought stress in pea nodules [32]. FBA mRNA levels was increased by high salinity, drought, ABA in maize [33]. The rest proteins such as delta 3,5-delta 2,4-dienoyl-CoA isomerase (spot 8) and bifuntional 3-phosphoadenosine 5-phosphosulfate synthetase 2 (spot 23) were little prior functional studies under water deficit in maize. Further research is required to determine the roles of these metabolism-related proteins under water deficit in maize.

Another main group of proteins influenced by water-deficit stress was that of stress-related proteins. Levels of two heat shock proteins (HSPs; spots 2 and 5), glutathione transferase 5 (GT; spot 3), ascorbate peroxidase (APX; spot 6), cysteine proteinase inhibitor (CPI; spot 10), serine/threonine-protein phosphatase 1 (PP1; spot 15), and peroxidase 66 (POX; spot 9) were increased in drought-stressed samples contrasted with control samples (Fig. 4; Table 1). Plants have evolved several strategies to diminish the damage caused by reactive oxygen species (ROS) [23]. An increase in the levels of HSP and GT has been previously documented under several stress conditions, including drought, salinity, ROS, and cold [34]. Similarly, the up-regulation of APX, GT, and HSP gene transcription or increase in the levels of the corresponding proteins has been reported in the maize inbred lines Han21, Ye478, and KS140 under water-deficit stress [19, 23]. From our research, we found that most of stress-related proteins were up-regulated by water deficit. These data suggest that these stress-related proteins may be important in plant tolerance to water deficit.

The oxygen evolving enhancer protein (OEE) is nuclear encoded and peripherally bound to photosystem II (PSII) on the luminal side of the thylakoid membrane. The expression level of OEE increases under abiotic stresses, such as salinity [35]. In this study, expression levels of OEE3 were decreased in both maize hybrids under water deficit compared with control samples (Fig. 4; Table 1). Additionally, crosstalk between proteins entangled in the response to water deficit and in photosynthesis has been suggested; it is possible that signaling factors involved in the response to water deficit reduce the levels of proteins involved in photosynthesis.

To determine the transcript levels of genes encoding the differentially accumulated proteins identified in this study, semi-quantitative RT-PCR analysis was carried out using gene-specific primers. The expression of genes encoding 10 randomly selected proteins, including HSP (spot 2), HSP17.4 (spot 5), GT (spot 3), CPI (spot 10), TPI (spot 11), OEE3 (spot 12), CA (spot 16), AGA (spot 20), GA3PD (spot 21), and IDH (spot 22), was examined (Additional file 1: Table S1; Fig. 5). The expression levels of most of the genes correlated with the protein levels under water-deficit conditions, except for OEE3 in GPOK (Fig. 5).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

References

Araus JL, Slafer GA, Reynolds MP, Royo C (2002) Plant breeding and water relations in C3 cereals: what to breed for? Ann Bot 89:925–940

Dai A (2012) Increasing drought under global warming in observations and models. Nat Clim Change 3:52–58

Lawlor DW, Tezara W (2009) Causes of decreased photosynthetic rate and metabolic capacity in water-deficient leaf cells: a critical evaluation of mechanisms and integration of processes. Ann Bot 103:543–549

Pinheiro C, Chaves MM (2011) Photosynthesis and drought: can we make metabolic connections from available data? J Exp Bot 62:869–882

Seki M, Umezawa T, Urano K, Shinozaki K (2007) Regulatory metabolic networks in drought stress responses. Curr Opin Plant Biol 10:296–302

Chaves MM, Maroco JP, Pereira JS (2003) Understanding plant responses to drought from genes to the whole plant. Funct Plant Biol 30:239–264

Mahajan S, Tuteja N (2005) Cold, salinity and drought stresses: an overview. Arch Biochem Biophys 444:139–158

Cordell D, Rosemarin A, Smit J, Schröder A (2011) Towards global phosphorus security: a systems framework for phosphorus recovery and reuse options. Chemosphere 84:747–758

Lobell DB, Bänziger M, Magorokosho C, Vivek B (2011) Nonlinear heat effects on African maize as evidenced by historical yield trials. Nat Clim Change 1:42–45

Bassetti P, Westgate ME (1993) Water deficit affects receptivity of maize silks. Crop Sci 33:279–282

Farré I, Faci JM (2006) Comparative response of maize (Zea mays L.) and sorghum (Sorghum bicolor L. Moench) to deficit irrigation in a Mediterranean environment. Agric Water Manag 83:135–143

Yordanov I, Velikova V, Tsonev T (2000) Plant responses to drought, acclimation, and stress tolerance. Photosynthetica 38:171–186

Lizana C, Wentworth M, Martinez JP, Villegas D, Meneses R, Murchie EH, Pastenes C, Lercari B, Vernieri P, Horton P, Pinto M (2006) Differential adaptation of two varieties of common bean to abiotic stress: I. Effects of drought on yield and photosynthesis. J Exp Bot 57:685–697

Nayyar H, Gupta D (2006) Differential sensitivity of C3 and C4 plants to water deficit stress: association with oxidative stress and antioxidants. Environ Exp Bot 58:106–113

Benešová M, Holá D, Fischer L, Jedelský PL, Hnilička F, Wilhelmová N, Rothová O, Kočová M, Procházková D, Honnerová J, Fridrichová L, Hniličková H (2012) The physiology and proteomics of drought tolerance in maize: early stomatal closure as a cause of lower tolerance to short-term dehydration? PLoS ONE 7:e38017

Riccardi F, Gazeau P, Jacquemot MP, Vincent D, Zivy M (2004) Deciphering genetic variations of proteome responses to water deficit in maize leaves. Plant Physiol Biochem 42:1003–1011

de Vienne D, Leonardi A, Damerval C, Zivy M (1999) Genetics of proteome variation for QTL characterization: application to drought-stress responses in maize. J Exp Bot 50:303–309

Kakumanu A, Ambavaram MM, Klumas C, Krishnan A, Batlang U, Myers E, Grene R, Pereira A (2012) Effects of drought on gene expression in maize reproductive and leaf meristem tissue revealed by RNA-Seq. Plant Physiol 160:846–867

Zheng J, Fu J, Gou M, Huai J, Liu Y, Jian M, Huang Q, Guo X, Dong Z, Wang H, Wang G (2010) Genome-wide transcriptome analysis of two maize inbred lines under drought stress. Plant Mol Biol 72:407–421

Smart RE, Bingham GE (1974) Rapid estimates of relative water content. Plant Physiol 53:258–260

Kim SG, Lee JS, Kim JT, Kwon YS, Bae DW, Bae HH, Son BY, Baek SB, Kwon YU, Woo MO, Shin SH (2015) Physiological and proteomic analysis of the response to drought stress in an inbred Korean maize line. Plant Omics J 8:159–168

Kim SG, Kim ST, Kang Y, Wang Y, Kim W, Kang KY (2008) Proteomic analysis of reactive oxygen species (ROS)-related proteins in rice roots. Plant Cell Rep 27:363–375

Kim SG, Bae HH, Jung HJ, Lee JS, Kim JT, Go TH, Son BY, Baek SB, Kwon YU, Woo MO, Shin SH (2014) Physiological and protein profiling response to drought stress in KS141, a Korean maize inbred line. J Crop Sci Biotechnol 17:273–280

Aparcio-Tejo P, Boyer JS (1982) Significance of accelerated leaf senescence at low water potentials for water loss and grain yield in maize. Crop Sci 23:1198–1202

Sah SK, Zamora OB (2005) Effect of water deficit at vegetative and reproductive stages of hybrid, open pollinated variety and local maize. J Inst Agric Anim Sci 25:37–42

Shin SH, Lee JS, Kim SG, Go TH, Shon JY, Kang SG, Lee JS, Bae HH, Kim JT, Shim KB, Yang WH, Woo MO (2015) Yield of maize (Zea mays L.) logistically declined with increasing length of the consecutive visible wilting days during flowering. J Crop Sci Biotechnol 15:237–248

Wolfe DW, Henderson DW, Hsiao TC, Alvino A (1988) Interactive water and nitrogen effects on senescence of maize. I. Leaf area duration, nitrogen distribution, and yield. Agron J 80:859–864

Denmead OT, Shaw RH (1960) The effects of soil moisture stress at different stages of growth on the development and yield of corn. Agron J 52:272–274

Song Y, Birch C, Qu S, Doherty A, Hanan J (2010) Analysis and modelling of the effects of water stress on maize growth and yield in dryland conditions. Plant Prod Sci 13:199–208

Saglam A, Kadioglu A, Demiralay M, Terzi R (2014) Leaf rolling reduces photosynthetic loss in maize under severe drought. Acta Bot Croat 73:315–332

Cramer GR, Van Sluyter SC, Hopper DW, Pascovici D, Keighley T, Haynes PA (2013) Proteomic analysis indicates massive changes in metabolism prior to the inhibition of growth and photosynthesis of grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) in response to water deficit. BMC Plant Biol 13:49

Gálvez L, González EM, Arrese-Igor C (2005) Evidence for carbon flux shortage and strong carbon/nitrogen interactions in pea nodules at early stages of water stress. J Exp Bot 56:2551–2561

Hu X, Wu X, Li C, Lu M, Liu T, Wang Y, Wang W (2012) Abscisic acid refines the synthesis of chloroplast proteins in maize (Zea mays) in response to drought and light. PLoS ONE 7:e49500

Pechanova O, Taká T, Samaj J, Pechan T (2013) Maize proteomics: an insight into the biology of an important cereal crop. Proteomics 13:637–662

Sugihara K, Hanagata N, Dubinsky Z, Baba S, Karube I (2000) Molecular characterization of cDNA encoding oxygen evolving enhancer protein 1 increased by salt treatment in the mangrove Bruguiera gymnorrhiza. Plant Cell Physiol 41:1279–1285

Acknowledgements

This work was carried out with financial support from the Cooperative Research Program for Agriculture Science and Technology Development (Project title: Study for physiological response to waterlogging stress and building up the screening method in maize, Project No.: 447 PJ010200022018), Rural Development Administration (RDA), Republic of Korea, and the 2018 Postdoctoral Fellowship of National Institute of Crop Science, RDA, Republic of Korea.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SGK, SS and WTJ conceived and designed the experiments. SGK, SS and WTJ performed most of experiments and wrote the manuscript. JSL, HHB, JTK, BYS, SLK and SBB conducted secondary experiment and data analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1.

Primers used for semi-quantitative RT-PCR.

Additional file 2.

Effect of water deficit on the growth of Korean F1 maize hybrids, Ilmichal (Ilmi) and Gwangpyeongok (GPOK). Lengths of stem (A) and ear (B) of well-watered (control) and drought-stressed plants of Ilmi and GPOK are shown. Water supply was withheld for 10 days at the flowering stage. Data represent mean ± SEM. Statistically significant differences between control and drought-stressed samples were determined using Fisher’s LSD test (α = 0.05).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, S.G., Lee, JS., Bae, H.H. et al. Physiological and proteomic analyses of Korean F1 maize (Zea mays L.) hybrids under water-deficit stress during flowering. Appl Biol Chem 62, 32 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13765-019-0438-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13765-019-0438-0