Abstract

Our previous study showed that the ethanol extract of Dioscorea batatas Decne (Chinese yam) peel upregulated certain antioxidant enzymes and had the anti-inflammatory activity. In this study, 2, 7-dihydroxy-4, 6-dimethoxy phenanthrene (DDP) was isolated from yam peel extract as a potent antioxidative enzyme inducer through bioassay-guided fractionation using HepG2-ARE cells, and subjected to examination for its anti-inflammatory activity as well as antioxidant activity. DDP decreased the levels of inflammatory mediators in LPS-stimulated Raw 264.7 macrophage and reduced the level of reactive oxygen species in tert-butyl hydroperoxide-challenged Raw 264.7 cells. Moreover, DDP enhanced the expression of nuclear factor (erythroid-derived 2)-like 2 (Nrf2) and its downstream heme oxygenase-1 proteins while it decreased the expression of iNOS, COX-2, proinflammatory cytokines via nuclear factor-κB pathway. However, the combinatorial treatment with DDP and the inhibitor of Nrf2 or HO-1 activity did not affect the levels of inflammatory biomarkers, suggesting that anti-inflammatory action by DDP is achieved by the mechanism independent of Nrf2 signaling pathway. In conclusion, DDP was found to be a strong antioxidant and anti-inflammatory agent and warrants further in vivo efficacy study for future use as a functional food ingredient.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chronic inflammation increases the risk of many diseases such as intestinal bowel diseases, colorectal cancer, cardiovascular disease, and neurodegenerative disease in which oxidative stress plays a critical role [1,2,3]. It is widely known that inflammatory responses are mediated by upregulation of nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) and its downstream genes including inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2). NF-κB activation is influenced by ROS and leads to upregulation of antioxidant proteins, demonstrating that NF-κB and ROS influence each other in a positive feedback loop [4].

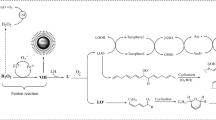

ROS are defined as reduced metabolites of oxygen that have strong oxidizing capabilities [5]. The proper levels of ROS acts as signaling molecules that regulate cell growth, the adhesion of cells, differentiation, and apoptosis [6,7,8]. Increased ROS can activate inflammatory signaling which includes pro-inflammatory signaling protein MAPK and the transcription factor NF-κB [9, 10], and also cause the oxidation of protein and lipid and the damage of DNA. Thus, the inflammatory responses are regulated by the redox balance governed by cellular antioxidant machinery [5, 11].

Nuclear factor (erythroid-derived 2)-like 2 (Nrf2), a transcription factor, induces a variety of phase 2 detoxifying/inducible antioxidant enzymes including heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), NAD(P)H quinone dehydrogenase 1 (NQO1), glutathione reductase (GR), and gamma-glutamylcysteine synthetase (γ-GCS). Multiple studies have demonstrated that hyperactivation of Nrf2 can suppress NF-κB-mediated inflammation [12, 13]. Nrf2 induces the expression of HO-1 gene by increasing mRNA and protein expression. HO-1 and its metabolites including carbon monoxide have been reported to have strong anti-inflammatory effects by inhibiting of NF-κB signaling. As Nrf2/HO-1 axis plays an important role in anti-inflammatory function, Nrf2 and its downstream antioxidant enzymes could be promising therapeutic targets in inflammatory diseases [14,15,16,17,18].

Our previous study also showed that Dioscorea batatas Decne extract effectively decreased the levels of inflammatory mediators in LPS-stimulated macrophage and DSS-induced colitis mice model [19]. However, the yam peel components responsible for anti-inflammatory effect have not been identified so far. Therefore, this study was conducted to isolate the yam peel component(s) with anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activities through bioassay-guided fractionation using HepG2-ARE cells, leading to the isolation of a couple of active compounds including phenanthrene derivatives. That is, chromatographic fractions showing strong antioxidant enzyme-inducing activity were serially collected and narrowed down to the component(s) with the strongest antioxidant capacity, subsequently examined its anti-inflammatory activity.

Materials and methods

Plant material

The peel of D. batatas Decne (DBD; a synonym for Dioscorea polystachya Turcz.), commonly called Chinese yam was obtained from the Forest Resources Development Institute of Gyeongsangbuk-do (Andong, S. Korea).

Extraction and isolation of Dioscorea batatas Decne peel

The peel (7 kg) of D. batatas Decne was extracted with 95%(v/v) ethanol (10 L) for 48 h at room temperature. The ethanol extract was concentrated, and then partitioned in a separatory funnel with the equivalent amount of hexane, ethyl acetate, butanol and water, sequentially. Ethyl acetate-soluble fraction with the highest antioxidant enzyme-inducing activity was dissolved with DCM:MeOH (1:1, v/v) and further fractioned on size exclusion chromatography filled with Sephadex® LH20 resin (80 × 400 mm) using mobile phase, DCM:MeOH (1:1, v/v). The eighth fraction among total 13 fractions was purified by reversed phase HPLC using a gradient mixture of acetonitrile/water (39:61 (0–44 min) → 100:0 (44.01–60 min)) to acquire 2,7-dihydroxy-4,6-dimethoxy phenanthrene (DDP, 4.9 mg).

NMR data acquisition

The isolated compound (DDP) was dissolved in acetone-d6, and 1H and 13C nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra were obtained from a Bruker Ascend™ (1H-500 MHz, 13C-125 MHz (Billerica, MA, USA) spectrometer.

Cell culture

A murine macrophage cell line (Raw 264.7) was obtained from the Korean Cell Line Bank (KCLB, Seoul, S. Korea). The cells were cultivated in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS; Welgene, S. Korea) and 1% penicillin–streptomycin (Invitrogen/Thermo Fisher Scientific, Carlsbad, CA, USA), and kept at 37 °C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2/95% air under saturating humidity.

Cell viability assay

To test the cytotoxicity of DDP, a cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8; Dojindo Laboratories, Kumamoto, Japan) was used as previously described [20]. Cells were treated with various concentrations of DDP followed by incubation for 24 h. The absorbance, which is proportional to the number of living cells in each well, was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader (Sunrise™, Tecan Group Ltd., Männedorf, Switzerland).

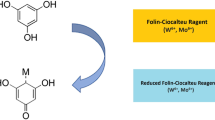

Antioxidant response element (ARE)-luciferase activity assay

To measure the transcriptional activity of ARE, luciferase reporter gene assay was conducted on HepG2-ARE as previously described [21]. The cells were treated with DDP in 0.5% FBS-containing culture medium for 24 h. The ARE-luciferase activity was measured using a luciferase assay system (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Sulforaphane (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA, 5 μM) was used as a positive control [22]. The luminescence was detected using a TD-20/20 luminometer (Turner Designs, Sunnyvale, CA, USA), and calibrated with the amount of total proteins. The values were then normalized against the control.

Detection of intracellular reactive oxygen species

The intracellular oxidative stress was assessed by measures of reduced 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (H2DCFDA; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), which is converted into oxidized and fluorescent 2′, 7′-dichlorofluorescein (DCF) by reactive oxygen species (ROS). Cells were plated into a black-bottom 96-well plate (Nunc, Rochester, NY, USA) at a density of 2 × 104 cells/well. After 24 h, cells were incubated with the various concentrations of DDP for another 24 h. Cells were treated with H2DCFDA (20 μM) for 30 min, and subsequently challenged by tert-butyl hydroperoxide (tBHP; 200 μM in 1% FBS-containing PBS) for 1 h. After 1 h-incubation in tBHP-containing PBS, fluorescence was measured at excitation and emission wavelengths of 485 nm and 535 nm, respectively, using a fluorescence microplate reader (Infinite 200; Tecan, Grodig, Austria).

Determination of nitric oxide (NO) production

Raw 264.7 cells were incubated with various concentrations of DDP and/or lipopolysaccharide (LPS, Sigma-Aldrich, 1 μg/mL), Tin protoporphyrin IX (SnPP, Enzo Life Sciences, Inc., Farmingdale, NY, 20 μM) and Brusatol (Carbosynth Ltd., Newbury, Berkshire, UK, 50 nM). After 24 h, the culture medium was then collected. The NO level in the culture medium was determined by measuring the nitrite content using the Griess reagent system (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). Dexamethasone (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA, 100 μM) was used as a positive control.

Measurement of inflammatory cytokine levels

The levels of cytokines present in the culture medium was measured using commercial ELISA kits for interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6 and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, (BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA). The culture medium was collected then centrifuged at 10,000 × g at 4 °C for 5 min. The supernatant was subjected to ELISA for each cytokine. Dexamethasone was used as a positive control.

Western blot analysis

Whole cell lysates were prepared by homogenizing in pre-cooled lysis buffer (20 mM Tris–HCl, 145 mM NaCl, 10%(v/v) glycerol, 5 mM EDTA, 1%(v/v) Triton-X and 0.5%(v/v) Nonidet). After centrifugation at 15,000 × g at 4 °C for 10 min, the supernatants were quantified for protein and denatured in sample buffer at 95 °C for 10 min. Alternatively, nuclear and cytoplasmic proteins were fractionated using NE-PER™ nuclear and cytoplasmic protein extraction kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific., Rockford, IL, USA), quantified and denatured. The proteins were then electrophoretically separated on sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel (SDS-PAGE) and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes (Merck Millipore Corp., Billerica, MA, USA). The membranes were blocked in 1%(w/v) bovine serum albumin (BSA) in Tris-buffered saline including 0.1% (v/v) Tween 20 (TBST). The primary antibodies used in this study were against COX-2, iNOS, HO-1, p65, Nrf2, lamin B or β-actin. The appropriate secondary antibodies conjugated with horse radish peroxidase (HRP) were used for each primary antibody. Protein bands were developed using SuperSignal™ West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (Pierce, Cheshire, United Kingdom), digitalized using ImageQuant LAS 4000 mini (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Little Chalfont, UK), and densitometrically analyzed using Image Studio Lite version 5.2 (LI-COR Biotechnology, Lincoln, NE, USA).

Statistical analysis

All the statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS software version 23.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Comparisons were conducted via one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Duncan’s multiple range test. The p values less than 0.05 were considered significant. Significant differences were indicated using different alphabetical letters.

Results and discussion

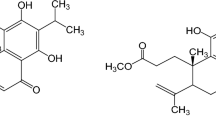

We previously observed that the ethanolic extract of Chinese yam peel had anti-inflammatory effect in LPS-stimulated macrophage and DSS-induced colitis mice model [19]. To find the potential bioactive substances in yam peel extract, we performed bioassay-guided fractionation for yam peel extract, followed by examination of the anti-oxidant and anti-inflammatory activities of each fraction. First, the extract was fractionated using solvent and size exclusion chromatography. Four fractions of D. batatas peel extract were tested for their antioxidant ability by measuring ARE-induction activity. Ethyl acetate (EA) fraction increased ARE-induction activity more highly than any other fractions. Therefore, EA fraction was further fractionated by size exclusion chromatography. Thirteen chromatographic fractions of EA layer were obtained and examined for their anti-oxidant or anti-inflammatory activities (Additional file 1: Fig. S3A, S3B). The chromatographic fraction #8 enhanced ARE-induction activity most significantly while decreased NO concentration in LPS-stimulated Raw 264.7 cells. Further purification of the fraction #8 using a preparative reverse phase HPLC resulted in five clear single peaks (#1–5) and two poorly resolved peaks (#6–7) (Additional file 1: Table S1). Unfortunately, the yield of peak #4 was not enough to conduct further experiments. Therefore, the anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activities were evaluated for 4 well-resolved single peaks (peak #1, 2, 3, 5). The compound represented by peak #1 was identified to be 2, 7-dihydroxy-4, 6-dimethoxy phenanthrene (DDP; Fig. 1a) through NMR and mass spectrometry while the other three peaks are under study for determination of molecular structure.

The isolation procedure of 2, 7-dihydroxy-4, 6-dimethoxy phenanthrene (DDP) from ethyl acetate fraction in D. batatas Decne peel extract was detailed in Additional file 1: Fig. S1. The chemical structure of DDP was identified through analysis of 1H, 13C NMR spectra as shown in Additional file 1: Fig. S2(A, B) along with MS spectroscopic data. The compound showed the chemical characteristics described below and identified as a 2, 7-dihydroxy-4, 6-dimethoxy phenanthrene by comparison with previous reports [23, 24]. Electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry (ESI–MS; positive mode) m/z 271.1[M + H]+; 1H NMR δ : 4.05 (3H, s, 6-OCH3), 4.14 (3H, s, 4-OCH3), 6.82 (1H, d, J = 2.25 Hz, H-3), 6.92 (1H, d, J = 2.33 Hz, H-1), 7.27 (1H, s, H-8), 7.46 (1H, d, J = 8.77 Hz, H-10), 7.55 (1H, d, J = 8.76, H-9), 9.14 (1H, s, H-5); 13C NMR δ: 160.09 (C-4), 155.96 (C-2), 148.21 (C-6), 145.72 (C-7), 135.61 (C-10a), 128.04 (C-4b), 127.76 (C-10), 125.37 (C-8a), 125.3 (C-9), 115.32 (C-4a), 112.24 (C-8), 109.45 (C-5), 106.26 (C-1), 99.85 (C-3), 56.02 (C-4, OCH3), 55.83 (C-6, OCH3).

Phenanthrene, a skeleton of DDP, is a polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon composed of three fused benzene rings. It has been previously reported to have biological activities including anticancer, antimicrobial, spasmolytic, anti-allergic, anti-inflammatory, and antiplatelet aggregation activities [25,26,27,28,29,30,31]. A few phenanthrene derivatives have been reported in the Dioscoreaceae, Hepaticae class and Betulaceae families [32].

DDP reduced NO concentration in LPS-stimulated macrophage and induced ARE-luciferase in HepG2-ARE cells (Additional file 1: Fig. S3(C-F)). DDP was also shown to have relatively low cytotoxicity for Raw 264.7 macrophage cells as examined by CCK-8 assay. DDP did not affect the cell viability at 5 μg/mL or less while it showed a slight reduction in cell viability at 10 μg/mL (Fig. 1b).

Inflammatory responses are generally mediated by proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, TNF-α and IL-6, which are, in turn, controlled by NF-κB, a key inflammatory transcription factor [33, 34]. To investigate the anti-inflammatory effects of DDP, Raw 264.7 cells were exposed to different concentrations of DDP for 24 h in the absence or presence of LPS. LPS treatment increased NO production and pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, TNF-α and IL-6, but the addition of DDP inhibited LPS-mediated increase of NO production and IL-1β in a dose-dependent manner. However, the levels of TNF-α and IL-6 were not affected by the compound (Fig. 2a–d).

Anti-inflammatory effects of DDP on LPS-activated Raw 264.7 macrophage. Cellular inflammatory response was provoked by LPS in Raw 264.7 cells. After 24 h incubation in the absence or presence of DDP, each culture medium was collected. The levels of extracellular NO (a) and inflammatory cytokines, including IL-1β, TNF-α and IL-6 (b–d) were analyzed. Intracellular protein expression levels of iNOS, COX-2 and nuclear p65 in LPS-activated Raw 264.7 cells were quantitatively analyzed (e, f). Bars (values) not sharing common letter indicate statistically significant difference from each other (p < 0.05)

In addition, DDP significantly suppressed LPS-induced expression of cytosolic iNOS and COX-2 proteins (Fig. 2e). The nuclear level of p65 was also significantly reduced by the compound in LPS-stimulated Raw 264.7 cells (Fig. 2f), suggesting that DDP could exert anti-inflammatory activity by suppressing NF-κB signaling pathway.

As excessive ROS could activate inflammatory signaling, it is important to control redox balance by cellular antioxidant machinery [5, 11]. The expression of reporter luciferase gene connected to ARE sequence present in the promoter region of inducible antioxidant enzyme genes was increased in DDP-treated human hepatoma HepG2-ARE cells (Fig. 3a), suggesting that DDP could induce antioxidant enzymes through Nrf2/ARE-signaling pathway and exert a strong antioxidant activity. To examine whether DDP can decrease the intracellular ROS level, Raw 264.7 cells were treated with various concentrations of DDP following treatment with tBHP. As expected, DDP significantly reduced intracellular ROS level induced by tBHP (Fig. 3b).

Antioxidant effect of DDP. a Dose-dependent reporter activity induction by DDP in HepG2-ARE cells. b Suppressive activity of DDP against tBHP-induced ROS production in Raw 264.7 cells. c Increased expression of HO-1 and nuclear Nrf2 translocation by DDP in Raw 264.7 cells. Bars (values) not sharing common letter indicate statistically significant difference from each other (p < 0.05)

Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway was known to downregulate the proinflammatory cytokines including IL-6 and TNF-α as well as other inflammatory mediators such as COX-2 and iNOS [16, 17, 35]. Therefore, we further examined whether DDP could promote Nrf2-mediated antioxidant enzyme expression in Raw 264.7 cells. When the cells were treated with DDP, the expression of Nrf2 and HO-1 was increased (Fig. 3c) but the expression of another antioxidant enzymes such as NQO1 and γ-GCS remained unchanged (data not shown).

To further investigate whether Nrf2/HO-1 axis plays a role in DDP-mediated anti-inflammatory activity, Raw 264.7 cells were treated with DDP in the absence or presence of tin protoporphyrin (SnPP) or brusatol, which is an inhibitor of HO-1 and Nrf2, respectively. While DDP suppressed NO production and IL-1β concentration induced by LPS (Fig. 2a, b), co-treatment of DDP with brusatol or SnPP did not attenuate the repression of IL-1 β and NO production mediated by DDP (Fig. 4a, b). In addition, DDP significantly reduced the expression of LPS-induced iNOS and COX-2. However, the inhibition of Nrf2 or HO-1 by brusatol or SnPP did neither affect nor attenuate the effect of DDP on the expression of iNOS and COX-2 (Fig. 4c). These results suggest that anti-inflammatory effect of DDP is not directly associated with Nrf2 or HO-1 activity. There is another possibility that NF-κB signaling pathway is irreversibly altered by DDP and could not be restored at any means such as Nrf2 signaling pathway or its downstream proteins.

Effects of Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway on DDP-mediated anti-inflammatory activities. Raw 264.7 cells were cultured with 5 μg/mL of DDP with LPS in the absence or presence of SnPP (20 μM) of Brusatol (50 nM), each culture medium was collected. The levels of extracellular NO (a) and IL-1β (b) were analyzed. Intracellular protein expression levels of iNOS, COX-2 in LPS-activated Raw 264.7 cells were quantitatively analyzed (c). Bars (values) not sharing common letter indicate statistically significant difference from each other (p < 0.05)

In conclusion, DDP attenuated inflammatory response and enhanced antioxidant activities on LPS-stimulated Raw 264.7 cells. Thus, DDP poses potential as a natural therapeutic agent or dietary supplement for prevention of a multiple inflammatory diseases, such as inflammatory bowel disease, rheumatoid arthritis, atherosclerosis, systemic lupus erythematosus, type I diabetes, multiple sclerosis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma.

Change history

06 July 2019

After the publication of the article [1], it was found that the Received and Accepted dates were missing inadvertently in the originally published version.

References

Kim ER, Chang DK (2014) Colorectal cancer in inflammatory bowel disease: the risk, pathogenesis, prevention and diagnosis. World J Gastroenterol 20:9872–9881

Axelrad JE, Lichtiger S, Yajnik V (2016) Inflammatory bowel disease and cancer: the role of inflammation, immunosuppression, and cancer treatment. World J Gastroenterol 22:4794–4801

Reuter S, Gupta SC, Chaturvedi MM, Aggarwal BB (2010) Oxidative stress, inflammation, and cancer: how are they linked? Free Radic Biol Med 49:1603–1616

Morgan MJ, Liu ZG (2011) Crosstalk of reactive oxygen species and NF-kappaB signaling. Cell Res 21:103–115

Mittal M, Siddiqui MR, Tran K, Reddy SP, Malik AB (2014) Reactive oxygen species in inflammation and tissue injury. Antioxid Redox Signal 20(7):1126–1167

Liu JY, Yang FL, Lu CP, Yang YL, Wen CL, Hua KF, Wu SH (2008) Polysaccharides from Dioscorea batatas induce tumor necrosis factor-alpha secretion via Toll-like receptor 4-mediated protein kinase signaling pathways. J Agric Food Chem 56:9892–9898

Droge W (2002) Free radicals in the physiological control of cell function. Physiol Rev 82:47–95

Thannickal VJ, Fanburg BL (2000) Reactive oxygen species in cell signaling. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 279:L1005–L1028

Halliwell B (2007) Biochemistry of oxidative stress. Biochem Soc Trans 35:1147–1150

Jenner P (2003) Oxidative stress in Parkinson’s disease. Ann Neurol 53:S26–S36

Harijith A, Ebenezer DL, Natarajan V (2014) Reactive oxygen species at the crossroads of inflammasome and inflammation. Front Physiol 5:352

Zhang M, An C, Gao Y, Leak RK, Chen J, Zhang F (2013) Emerging roles of Nrf2 and phase II antioxidant enzymes in neuroprotection. Prog Neurobiol 100:30–47

Zhu H, Jia Z, Zhang L, Yamamoto M, Misra HP, Trush MA, Li Y (2008) Antioxidants and phase 2 enzymes in macrophages: regulation by Nrf2 signaling and protection against oxidative and electrophilic stress. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 233:463–474

Chi X, Yao W, Xia H, Jin Y, Li X, Cai J, Hei Z (2015) Elevation of HO-1 expression mitigates intestinal ischemia-reperfusion injury and restores tight junction function in a rat liver transplantation model. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2015:986075

Choi YH (2016) The cytoprotective effect of isorhamnetin against oxidative stress is mediated by the upregulation of the Nrf2-dependent HO-1 expression in C2C12 myoblasts through scavenging reactive oxygen species and ERK inactivation. Gen Physiol Biophys 35:145–154

Kuhn AM, Tzieply N, Schmidt MV, von Knethen A, Namgaladze D, Yamamoto M, Brune B (2011) Antioxidant signaling via Nrf2 counteracts lipopolysaccharide-mediated inflammatory responses in foam cell macrophages. Free Radic Biol Med 50:1382–1391

Nikam A, Ollivier A, Rivard M, Wilson JL, Mebarki K, Martens T, Dubois-Randé JL, Motterlini R, Foresti R (2016) Diverse Nrf2 activators coordinated to cobalt carbonyls induce heme oxygenase-1 and release carbon monoxide in vitro and in vivo. J Med Chem 59:756–762

Kim W, Kim HU, Lee HN, Kim SH, Kim C, Cha YN, Joe Y, Chung HT, Jang J, Kim K, Suh YG, Jin HO, Lee JK, Surh YJ (2015) Taurine chloramine stimulates efferocytosis through upregulation of Nrf2-mediated heme oxygenase-1 expression in murine, acrophages: possible involvement of carbon monoxide. Antioxid Redox Signal 23:163–177

Lim JS, Oh J, Byeon S, Lee JS, Kim JS (2018) Protective effect of Dioscorea batatas peel extract against intestinal inflammation. J Med Food 21:1204–1217

Oh J, Jeon SB, Lee Y, Lee H, Kim J, Kwon BR, Yu KY, Cha JD, Hwang SM, Choi KM, Jeong YS (2015) Fermented red ginseng extract inhibits cancer cell proliferation and viability. J Med Food 15:421–428

Kim BR, Hu R, Keum YS, Hebbar V, Shen G, Nair SS, Kong AN (2003) Effects of glutathione on antioxidant response element-mediated gene expression and apoptosis elicited by sulforaphane. Cancer Res 63:7520–7525

Woo YJ, Oh J, Kim JS (2017) Suppression of Nrf2 by Chestnut Leaf extract increases chemosensitivity of breast cancer stem cells to paclitaxel. Nutrients 9:760

Takasugi M, Kawashima S, Monde K, Katsui N, Masamune T, Shirata A (1987) Antifungal compounds from Dioscorea batatas inoculated with Pseudomonas cichorii. Phytochemistry 26:371–375

Leong YW, Kang CC, Harrison LJ, Powell A (1997) Phenanthrenes, dihydrophenanthrenes and bibenzyls from the orchid Bulbophyllum vaginatum. Phytochemistry 44:157–165

Xue Z, Li S, Wang S, Wang Y, Yang Y, Shi J, He L (2006) Mono-, Bi-, and triphenanthrenes from the tubers of Cremastra appendiculata. J Nat Prod 69:907–913

Lin YL, Huang RL, Don MJ, Kuo YH (2000) Dihydrophenanthrenes from Spiranthes sinensis. J Nat Prod 63:1608–1610

Aquino R, Conti C, De Simone F, Orsi N, Pizza C, Stein ML (1991) Antiviral activity of constituents of Tamus communis. J Chemother 3:305–309

Kostecki K, Engelmeier D, Pacher T, Hofer O, Vajrodaya S, Greger H (2004) Dihydrophenanthrenes and other antifungal stilbenoids from Stemona cf. pierrei. Phytochemistry 65:99–106

Pacher T, Seger C, Engelmeier D, Vajrodaya S, Hofer O, Greger H (2002) Antifungal stilbenoids from Stemona collinsae. J Nat Prod 65:820–827

Matsuda H, Morikawa T, Xie H, Yoshikawa M (2004) Antiallergic phenanthrenes and stilbenes from the tubers of Gymnadenia conopsea. Planta Med 70:847–855

Adams M, Pacher T, Greger H, Bauer R (2005) Inhibition of leukotriene biosynthesis by stilbenoids from Stemona species. J Nat Prod 68:83–85

Kovacs A, Vasas A, Hohmann J (2008) Natural phenanthrenes and their biological activity. Phytochemistry 69:1084–1110

Medzhitov R (2008) Origin and physiological roles of inflammation. Nature 454:428–435

Medzhitov R (2007) Recognition of microorganisms and activation of the immune response. Nature 449:819–826

Wunder C, Potter RF (2003) The heme oxygenase system: its role in liver inflammation. Curr Drug Targets Cardiovasc Haematol Disord 3:199–208

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by Forest Resources Development Institute of Gyeongsanbuk-do, Andong, South Korea (2019).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DH, JO and J-SK conceived and designed the experiments. JSL and MJG performed the experiments, collected and analyzed the data. JSL, JO, DH and J-SK interpreted and discussed the data. JSL financially supported. JSL and J-SK wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original version of this article was revised: The history dates information were missing in the originally published version. Received and Accepted dates were added in the article

Additional file

Additional file 1.

Fig. S1. Schematic diagram of extraction and isolation procedure for 2, 7-dihydroxy-4, 6-dimethoxy phenanthrene. Table S1. Yield of eight compounds of chromatographic fraction #8. Values in parenthesis represent actual weight in milligram obtained from 143.5 mg of fraction #8. Fig. S2. 1H NMR spectrum of 2,7-dihydroxy-4,6-dimethoxyphenanthrene 500 MHz, Acetone-d6, (A), and 13C NMR spectrum of DDP 125 MHz, Acetone-d6 (B). Fig. S3. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities of chromatographic fractions of ethylacetate fraction. (A) ARE-luciferase induction activities of thirteen fractions in HepG2-ARE cells. (B) Extracellular NO levels in LPS-activated RAW 264.7 cells cultured with thirteen fractions. (C) ARE-luciferase induction activities of four subfractions of chromatographic #8 fraction in HepG2-ARE cells. (D) Extracellular NO levels in LPS-activated RAW 264.7 cells cultured with four subfractions. (E–F) Effect of isolated compounds on the expression of inflammation-related proteins and Nrf2-mediated antioxidant enzymes in LPS-activated RAW 264.7 cells. Bars (values) not sharing common letter indicate statistically significant difference from each other (p < 0.05).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Lim, J.S., Hahn, D., Gu, M.J. et al. Anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects of 2, 7-dihydroxy-4, 6-dimethoxy phenanthrene isolated from Dioscorea batatas Decne. Appl Biol Chem 62, 29 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13765-019-0436-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13765-019-0436-2