Abstract

Background

Progressive language difficulties arise in many neurodegenerative conditions, causing significant impact upon patients and families. This occurs most obviously in primary progressive aphasia (PPA) but can also occur within other forms of progressive disease. In these cases, language decline may be significant, but as they are not the presenting or dominant symptom, may be overlooked in favour of more prominent cognitive, behaviour or motor deficits. To date, there has been no systematic investigation into non-primary progressive aphasia. This scoping review aims to describe the currently reported language impairments found in non-language-led dementias and identify their clinical relevance, defined as the impact on everyday living. It also seeks to identify the reported interventions for language impairment in this patient group to-date.

Method

We will conduct a scoping review of published studies that have assessed and/or treated aphasia in people diagnosed with a neurodegenerative condition other than primary progressive aphasia. The systematic search will include the electronic databases PubMed, MEDLINE, OVID-EMBASE, PsycINFO, and speechBITE, using search terms for specific non-language-led dementia subtypes. Findings will be mapped and described according to the type of language difficulties identified and rehabilitation approaches employed. Intervention studies will be evaluated for their methodological rigour using validated scales.

Discussion

This scoping review will provide an overview of the types of aphasia found in neurodegenerative conditions where language dysfunction is not the primary focus. Current treatment approaches (and gaps in the provision of treatment) will be identified.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The ability to express oneself and understand others through language is a central part of everyday life. When impaired, this can lead to disability and reduced quality of life [1]. Although memory impairments have typically been a point of focus when diagnosing and treating dementia (e.g., constituting an essential criteria in diagnostic classification systems such as ICD-10 until only recently), even early descriptions, such as those offered by Alois Alzheimer [2], include observations of language impairment within the context of neurodegenerative disease. In some cases, these impairments exceed those of other cognitive domains, a fact recognised by Marcel Mesulam, whose seminal work in the 1980s lead to the coining of the term ‘Primary Progressive Aphasia’ (PPA) [3, 4]. There are now three well described PPA syndromes [5] characterised by fluent speech with semantic breakdown, non-fluent speech with agrammatism and impaired repetition with phonologic errors. This recognition of PPA was an important step in raising awareness of non-memory-related disabilities associated with dementia, leading to the design of interventions that focused on improving expressive and receptive language abilities.

While non-primary in nature, progressive language difficulties have also been reported in many other neurodegenerative diseases. This includes reports in early-onset typical Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [6], Parkinson’s disease (PD) [7], dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) [8], posterior cortical atrophy (PCA) [9], behaviour variant frontotemporal dementia (bv-FTD) and frontotemporal dementia with motor neurone disease (MND) [10], as well as the atypical parkinsonian syndromes of progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) [11] and cortico-basal syndrome (CBS) [12]. Although clinically significant for patients and families, language symptoms in these conditions may be overlooked in favour of prominent non-language cognitive, behaviour or motor deficits. Thus, although such impairments may arise across a range of neurodegenerative syndromes, much is still to be learned regarding the nature and the prevalence of these language difficulties.

To date, systematic investigation of language deficits in these groups has been lacking, although it is likely that the language impairments which arise are variable in degree and severity, reflecting an overlapping continuum of profiles with the three classic primary progressive aphasia types. In recognising the commonalities between non-primary and primary progressive language impairments, there may arise the opportunity to use the knowledge gained from the treatment and support of people with PPA to assist those living with secondary language disorders.

We will therefore conduct a scoping review to map the literature concerning progressive language impairments in non-language-led neurodegenerative conditions (i.e. excluding PPA syndromes). In particular, we aim to provide an overview of the breadth and severity of language impairments, while also identifying current treatment approaches. In using a scoping review methodology rather than systematic review, we are able to combine information across various methodologies, including quantitative studies and case reports (common methodologies for research within this field), in a rigorous and systematic way.

Methods/design

We will follow the PRISMA guideline (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) extension for scoping review for conducting the review and preparing the report [13, 14]. See Additional file 1: PRISMA-ScR checklist.

Objectives

This scoping review seeks to answer the following questions:

-

What are the currently reported language impairments in non-language-led dementias?

-

What is the clinical significance of these impairments? E.g. impact on quality of life, activities of daily living or any other measures used to evaluate these constructs.

-

What are the reported language-based interventions for these patients?

Using the general framework outlined by Arksey and O’Malley [15] and guidance from the Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer’s Manual [16], we will systematically scope the literature in non-language-led dementias, including early onset AD, PCA, PD dementia, DLB, behavioural variant FTD, FTD with MND, PSP and CBD. Literature relating to typical, late-onset Alzheimer’s disease or vascular dementia will be excluded. In the case of late-onset Alzheimer’s disease, the language profile is already well-characterised and known to include anomia and deterioration of semantic memory, without a well-defined aphasia emerging until very late into the disease [17]. This profile differs from the young onset and atypical forms of the disease, where focal pathology within the language network can arise earlier in the course of the disease and result in full aphasia syndromes. In vascular dementia, the different types of vascular pathology (e.g. diffuse small vessel disease vs repeated major cerebrovascular accidents, which are also variable in their size and location) result in non-uniform patterns of cognitive change. As a result, there is a lack of consistency within the clinical identity from which to collate evidence in this subtype [18].

Information sources and search terms

The search will be conducted using the following databases: PubMed, MEDLINE, OVID-EMBASE, PsycINFO and speechBITE. The literature included will be indexed, published and peer-reviewed literature written in the English language with unlimited date range. Database-specific conventions and use of multiple search fields and filters will be customised for individual databases. English language filters will not be applied at this stage, with any resulting non-English articles removed manually during eligibility screening. In addition to the database searches, reference lists will be checked from key articles and reviews.

The following search terms will be used. These were developed in consultation with experienced researchers and librarians and were piloted:

(Early-onset Alzheimer’s disease OR early onset Alzheimer’s disease OR young-onset Alzheimer’s disease OR young onset Alzheimer’s disease OR Parkinson* dementia OR Parkinson* disease dementia OR dementia with Lewy bodies OR Lewy body dementia OR Posterior Cortical Atrophy OR frontotemporal dementia OR Pick’s disease OR Progressive Supranuclear Palsy OR Cortico-basal Syndrome OR cortico-basal degeneration OR corticobasal degeneration OR motor neurone disease OR FTD-MND OR MND-FTD OR ALS-FTD OR FTD-ALS) AND (language impairment OR communication disorder OR aphasia). See Additional file 2: Search Strategy for further details.

Data management and screening

All results from the database searches will be exported into the Endnote software. Duplicate records will be removed. The screening of the candidate articles and the selection of qualified studies will then be conducted using a multi-level title-first method [19]. The primary reviewer (ASG) will independently inspect all the citations. Reviewers two and three (AC and RG) will then independently inspect 50% of the citations each, screening firstly by title, and then by abstract, to obtain an agreement regarding inclusion or exclusion of the article. Any differences will be discussed, and if required, resolved by consultation with an additional researcher (SS). At full text screening, a 10% sample of the articles selected by the primary reviewer will be screened by reviewers two and three to ensure the reliability of selection.

Study selection

Population

Adults with a clinical diagnosis of early onset AD, PD dementia, DLB, PCA, PSP, CBS, bv-FTD or frontotemporal dementia in the context of motor neurone disease will be the focus of the review.

Concepts

Studies that assess and/or treat language difficulties in the target population will be included.

Context and comparators

Study selection will focus on articles published in English, where full text is available. Quantitative, mixed method, and case reports will be included. In some studies, comparison may be made between an intervention and a group who receive treatment as usual or no treatment. In other studies, this will be not applicable. Multiple reports that use data from the same study will be identified and collated, to avoid duplication of findings.

Exclusion criteria

-

Studies focused on late onset AD, vascular dementia, mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or a non-neurodegenerative disease diagnosis

-

Studies in which information regarding the nature of the language impairments is not provided

-

Studies which do not assess or treat language difficulties, including studies which only assess non-linguistic or non-cognitive aspects of communication (i.e. motor speech, voice, prosody, dysarthria and/or oral apraxia)

-

Treatments which are purely pharmacologically based or involve treatments such as electrical stimulation (transcranial magnetic stimulation or transcranial direct current stimulation).

-

Articles where full text is not readily available or is not in English

-

Studies where no original findings are presented (e.g. reviews/editorials/letters to editor)

-

Non-peer reviewed material

-

Conference abstracts

-

Errata/correction of no significance to required data

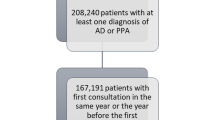

Exclusion decisions and characteristics of excluded studies will be recorded. The search findings will be summarised using a PRISMA flow diagram [20].

Data extraction and quality assessment

Information regarding type of language difficulties and treatment approaches taken will be extracted from each included article and recorded in a database. For studies describing the language impairments and impact upon everyday life, risk of bias will be evaluated using the Standard Quality Assessment Criteria for Evaluating Primary Research Papers from a Variety of Fields [21]. This method allows for simultaneous appraisal of both qualitative and qualitative dimensions of the same piece of work.

For quantitative studies reporting interventions, methodological rigour will be assessed using the PEDro-P scale [22] for group studies or the Risk of Bias in N-of-1 Trials [23] for single case designs, and where possible this information will be recorded directly from the speechBITE database (https://speechbite.com/rating-research-quality/).

Collating, summarising and reporting results

Overall results will be tabulated according to the population studied, including diagnosis and severity of language difficulties, type of study and treatment approaches employed. A modified version of the charting form from the JBI template [16] (see Additional file 3: Charting form) will be used to extract data from each study. This has been tested on pilot searches and will be used to show the breadth and severity of language impairments, leading to a basic numerical summary. For intervention studies, summaries will also be tabulated according to level of evidence, with the highest quality designs presented first.

Dissemination and ethics

The completed review will be written up and submitted for journal publication. Ethical approval is not required for this study.

Discussion

This scoping review will provide an overview of the extent and nature of the research evidence about language deficits in people with non-language-led dementia subtypes, and will identify current treatment approaches. In doing so, there will be an opportunity to identify gaps in service delivery and evaluate the methodological rigour of current research in this area.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets will be generated or analysed during the current study.

Abbreviations

- AD:

-

Alzheimer’s disease

- ALS:

-

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- bv-FTD:

-

Behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia

- CBS:

-

Cortico-basal syndrome

- DLB:

-

Dementia with Lewy bodies

- MCI:

-

Mild cognitive impairment

- MND:

-

Motor neurone disease

- PCA:

-

Posterior cortical atrophy

- PD:

-

Parkinson’s disease

- PPA:

-

Primary progressive aphasia

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

- PSP:

-

Progressive supranuclear palsy

References

Ruggero L, Nickels L, Croot K. Quality of life in primary progressive aphasia: what do we know and what can we do next? Aphasiology. 2019; 0(0): 1–22.

Stelzmann RA, Schnitzlein HN, Murtagh FR. An English translation of Alzheimer’s 1907 paper, “über eine eigenartige erkankung der hirnrinde”. Clin Anat. 1995;8(6):429–31.

Mesulam M. Slowly progressive aphasia without generalized dementia. Ann Neurol. 1982;11:592–8.

Mesulam M. Primary progressive aphasia—differentiation from Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol. 1987;22(4):533–4.

Gorno-Tempini ML, Hillis AE, Weintraub S, Kertesz A, Mendez M, Cappa SF, et al. Classification of primary progressive aphasia and its variants. Neurology. 2011;76(11):1006–14.

Imamura T, Takatsuki Y, Fujimori M, Hirono N, Ikejiri Y, Shimomura T, et al. Age at onset and language disturbances in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychologia. 1998;36(9):945–9.

Liu L, Luo X-G, Dy C-L, Ren Y, Feng Y, Yu H-M, et al. Characteristics of language impairment in Parkinson’s disease and its influencing factors. Transl Neurodegener. 2015;4(1):2.

Teichmann M, Migliaccio R, Kas A, Dubois B. Logopenic progressive aphasia beyond Alzheimer’s--an evolution towards dementia with Lewy bodies. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2013;84(1):113–4.

Crutch SJ, Lehmann M, Warren JD, Rohrer JD. The language profile of posterior cortical atrophy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2013;84(4):460–6.

Saxon JA, Thompson JC, Jones M, Harris JM, Richardson AM, Langheinrich T, et al. Examining the language and behavioural profile in FTD and ALS-FTD. J Neurol Neurosurg Amp Psychiatry. 2017;88(8):675.

Burrell JR, Ballard KJ, Halliday GM, Hodges JR. Aphasia in progressive supranuclear palsy: as severe as progressive non-fluent aphasia. J Alzheimers Dis JAD. 2018;61(2):705–15.

McMonagle P, Blair M, Kertesz A. Corticobasal degeneration and progressive aphasia. Neurology. 2006;67(8):1444–51.

Moher D, Stewart L, Shekelle P. Implementing PRISMA-P: recommendations for prospective authors. Syst Rev. 2016;5(1):15.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation the PRISMA-ScR statement. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73.

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32.

Peters M, Godfrey C, McInerney P, Munn Z, Trico A, Khalil H. Chapter 11: Scoping Reviews. In: Aromataris E, Munn Z, editors. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; 2020. JBI; Available from: https://wiki.jbi.global/display/MANUAL/Chapter+ 11%3A+Scoping+reviews. Cited 2020 Sep 24.

Weintraub S, Wicklund AH, Salmon DP. The neuropsychological profile of Alzheimer disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012;2(4) Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3312395/. Cited 2016 Jun 4.

O’Brien JT, Thomas A. Vascular dementia. The Lancet. 2015;386(10004):1698–706.

Mateen FJ, Oh J, Tergas AI, Bhayani NH, Kamdar BB. Titles versus titles and abstracts for initial screening of articles for systematic reviews. Clin Epidemiol. 2013;5:89–95.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535.

Kmet L, Lee R. Standard quality assessment criteria for evaluating primary research papers from a variety of fields: Heritage Foundation for Medical Research; 2004. Available from: https://era.library.ualberta.ca/items/48b9b989-c221-4df6-9e35-af782082280e. Report No.: 13. Cited 2019 Aug 21

Maher CG, Sherrington C, Herbert RD, Moseley AM, Elkins M. Reliability of the PEDro scale for rating quality of randomized controlled trials. Phys Ther. 2003;83(8):713–21.

Tate RL, Perdices M, Rosenkoetter U, Wakim D, Godbee K, Togher L, et al. Revision of a method quality rating scale for single-case experimental designs and n-of-1 trials: the 15-item Risk of Bias in N-of-1 Trials (RoBiNT) scale. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2013;23(5):619–38.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

ASG and JS receive funding from a grant jointly funded by the Economic and Social Research Council (UK), part of UK Research and Innovation, and the National Institute for Health Research (UK) (ES/S010467/1). The funding body has had no involvement in the design or conduct of this study or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SS was responsible for drafting the protocol manuscript, reviewing and revising the search strategy, will perform the duties outlined above as an additional reviewer, as required, and will contribute to mapping the results and drafting of final manuscript. ASG developed the concept for the review, contributed to the writing of the protocol, and was responsible for developing the search strategy, will perform the duties outlined above as the primary reviewer in the screening process and will contribute to mapping the results, and drafting of final manuscript. Both SS and ASG will act as guarantor of the review. RG and AC will conduct title screening, full text screening and will contribute to mapping the results. JS provided support for developing the search strategy, and advice on title screening and full text screening, and review of the protocol. All co-authors will advise on the interpretation of results, contribute to the critical revision of the manuscript and approve the final article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

PRISMA-ScR checklist

Additional file 2.

Search strategy

Additional file 3.

Charting form

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Savage, S.A., Suárez-González, A., Cassani, A. et al. Non-primary progressive language impairment in neurodegenerative conditions: protocol for a scoping review. Syst Rev 10, 32 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-021-01589-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-021-01589-6