Abstract

Background

Anemia is the most common hematologic disorder of children in the globe. There are fragmented and inconclusive study findings on under-five anemia in Ethiopia. Understanding the distribution of anemia is an important step for program planners and policymakers. Therefore, this systematic review was aimed to assess the pooled prevalence of anemia and associated factors with dietary diversity, food security, stunted, and deworming in Ethiopia.

Methods

We searched through African journals of online, Google Scholar, CINHAL, PubMed, Web of Science, Cochrane library, and Scopus. Reviewers used standardized format to extract the data. The data was exported to Stata version 11 software for analysis after extracted by Microsoft excel. The DerSimonian-Laird random-effect model was used to assess the pooled prevalence of under-five anemia. Variation between studies (heterogeneity) was assessed by I2 statistic test. Publication bias was assessed by the Egger test.

Result

From 561 studies, 16 articles were included in this review. The pooled prevalence of under-five anemia in Ethiopia was 44.83%. In subgroup analysis, the higher pooled prevalence of anemia was observed from children’s age less than 2 years old (50.36%) (95% CI 39.53, 61.18). Poor dietary diversity OR = 1.71 (1.10, 2.68), stunting OR = 2.59 (2.04, 3.28), food insecurity OR = 2.87 (1.25, 6.61), and not dewormed OR = 2.34 (1.77, 3.09) were predictors of under-five anemia.

Conclusion

The magnitude of under-five anemia in this study was extremely high. Therefore, increased coverage of supplementation and fortification programs, periodic deworming, feeding diversified food, supplement food for those who are stunted, and securing food in the households may all alleviate under-five anemia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Anemia is the major public health problem and diagnosed as below the reference interval value of hemoglobin or hematocrit concentration for healthy individuals of similar age, sex, and race with similar circumstances [1]. The threshold hemoglobin (Hb) level of under-five children for being anemic is less than 11.0 g/dl [1]. Low consumption and malabsorption of iron-rich foods are the most common causes of under-five anemia [2, 3]. It is prevalent in developing countries and results in poor in cognitive and motor development, low school performances, and exposes comorbid diseases [4].

Under-five anemia is the global health problem both in its severity and prevalence. Globally, 1.6 million people were affected by anemia and 47.4% of them were preschool children [5]. The prevalence of under-five anemia in Ethiopia was 56% [6].

Based on study findings in Ethiopia [7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22], the risk factors of anemia were stunting [7,8,9,10], poor dietary diversity [10,11,12,13], food insecurity [8, 10,11,12], timely initiation of complementary feeding [8, 11, 12], deworming [13, 14], wasting [7, 10], educational status [7, 10], maternal weight [7, 9], and antenatal care visits [7]. From these factors, four factors (food diversity, household food security, deworming, and stunting) were sorted for designing adaptable intervention and control strategies to the local context. Additionally, these factors are more prevalent in Ethiopia and given more emphasis regarding the prevention aspects of anemia.

The report of the magnitude of under-five anemia in Ethiopia was not conclusive and consistent. The prevalence of under-five anemia was high in the Somali region (72%) [13], whereas it was low in the Amhara region (13.06%) [21]. There is a high discrepancy among studies and no comprehensive systemic review done on under-five anemia in Ethiopia. This review was conducted to explain and understand the differences in various studies with sex, age, and severity of anemia. Therefore, the purpose of this study was aimed to review sherd evidences regarding the magnitude of under-five anemia in Ethiopia. This study generates epidemiological data in each region of a country and it is important for program planners and policymakers.

Methods

Search strategy

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guideline was used for this study [23]. Eligible research reports that addressed under-five anemia in Ethiopia were included in this study. Studies published were extensively searched through Google Scholar, CINAHL, PubMed, EMBASE, and Cochrane library. Searching was carried out using the following search terms such as “Anemia”, “Hemoglobin”, “Nutritional deficiency anemia”, Iron deficiency anemia “Under-five children”, “Prevalence”, Magnitude” “Risk factors”, “Predictors”, “Determinants”, “Children”, “Infants”, and “Ethiopia”. Searching words were used in combination and separately by using Boolean operators “OR”, “AND”, “Not”, or combined with this terms.

Study inclusion

Inclusion

Studies done in study designs of cross-sectional, case-control, and cohort reporting prevalence of under-five anemia in Ethiopia were incorporated in this study.

Exclusion criteria

Single case study design, qualitative study, research published in books, and research reports not accessed and not written in English were not included.

Measuring outcome variables

The outcome of this review is under-five anemia and it is diagnosed as hemoglobin (Hb) level is below 11.0 grams per deciliter and it is classified as mild (Hb = 10–10.9 g/dl), moderate (Hb = 7–9.9 g/dl), and severe anemia (Hb less than 7 g/dl) [13]. Secondly, the predictors of under-five anemia were carried out. The determinant factors included in this review were food diversity (poor versus good (poor diet diversity score is defined as children take less than four food groups per day)), deworming (yes versus no), food security (yes versus no), and stunting (yes versus no).

Quality assessment

The quality of included cross-sectional studies was evaluated with the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale [24]. Two independent reviewers extracted the data. Primary author, publication year, study design, study area, sample size, region of the study, age of participants, level of anemia, sex, and odd’s ratio of determinant factors were included in data extraction formats. The two authors (AB and TT) verified it. Methodological quality, tools deals with the comparability of the study and with the statistical analysis of each original study, and outcome were assessed.

Statistical analysis

Data were extracted with Microsoft Excel format and exported to the Stata version 11 software for analysis. The random-effect model was used to assess the pooled prevalence of under-five anemia. The variation between studies was quantified by the I2 statistic test [25]. Age of children was checked with the subgroup analysis. Furthermore, univariate meta-regression analysis was conducted with publication year, severity, sex, study design, region, sample size, and age of children. Fill trill analysis followed by Egger’s tests was used for assessing publication bias [26]. Log odds ratio was used to determine predictors of under-five anemia.

Results

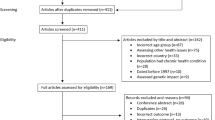

A total of 561 research papers that reported the prevalence and associated factors of under-five anemia in Ethiopia were searched by using previous prescribed databases. From the total, 360 research papers were not included due to irrelevancies and duplications. After reviewing of article titles and abstracts, around 184 research papers were excluded. One article was excluded due to quality of the study [27]. Finally, 16 studies were included in this review (Fig. 1).

Description of included studies

As showed in Table 1, all (16) research included in this systematic review was done by cross-sectional study designs and published from 2013 to 2018. A total of 11,924 under-five children were participated to assess the magnitude of under-five anemia. The included studies showed that the lowest prevalence of under-five anemia was from the Amhara region (13.6%) [21] while the highest prevalence (72%) was from the Somali region [13]. This review includes six studies from Amhara region [8, 14, 16, 19, 21, 22], five from SNNPR [10,11,12,13, 20], two from Somali region [9, 17], one from Addis Ababa [15], one from Tigray region [7], and one from Oromia region [18] (Table 1).

Risk of bias, publication bias, and heterogeneity of included studies

The risk of bias assessment tool was conducted to assess risk bias of each study [28]. Finally, summary assessment showed that majority of (75%) included studies had low risk of bias [7–18,], 18.75% had moderate risk of bias [19, 20, 22], and 6.25% had high risk of bias [28]. This review has publication bias as showed by Egger’s test result with a p value < 0.001. The Egger BO intercept was 0.075 (− 0.229, 0.378). Fill trill analysis was carried out (Fig. 2). The overall heterogeneity of included studies was I2 = 95.1% with a p value < 0.001, so random-effect model was used to estimate magnitude of under-five anemia.

Prevalence of under-five anemia in Ethiopia

The prevalence of under-five anemia ranges from 13.6% of 628 under-five children in Amhara region [21] to 72% of 397 under-five children in Somali region [13]. The DerSimonian-Laird random-effect model pooled prevalence of under-five anemia in Ethiopia was 44.83% (95% CI 36.71, 52.95). In subgroup analysis, 50.36% of anemia was found in the age range of 6–23 months old and 43% of them were from the age range of 6–59 months old (Fig. 3). The level of severity of anemia in this study was 17.56% (I2 = 92.9%), 26.12% (I2 = 93.5%), and 8.8% (I2 = 82%) had mild, moderate, and severe anemia, respectively. Regarding the sex of the child, anemia was more prevalent in male (31.3%) (I2 = 85.6%) compared with females (26.86%) (I2 = 55.2%) (Fig. 4).

Meta-regression

Univariate meta-regression was carried out with sample size, publication year, region, and age of children conducted but none of them was significant (Table 2).

Predictors of under-five anemia in Ethiopia

The association between food security, food diversity, stunting, and deworming with under-five anemia was carried out. In this meta-analysis, to identify the associated factors, five articles were used for poor dietary diversity [7, 8, 10,11,12], five for stunting [7,8,9,10, 14], three for food insecurity [10,11,12], and two for deworming [12, 13]. Infants who take less than four food groups per day were 1.71 times more likely to have childhood anemia. Infants from food insecure households were 2.87 times more likely to have anemia than their counterparts. The odds ratio of stunted children to develop anemia was 2.54. Infants who were not dewormed were 2.34 times more likely to have anemia than those who received anthelminthic (Fig. 5). Random-effect model was used due to high heterogeneity (I2 = 85.3% and p < 0.1). No publication bias was obtained in Egger’s test (0. 297).

Discussion

The prevalence of under-five anemia in this review was ranged from 13.06 to 72%. The highest prevalence of under-five anemia was from Somali region [13] while the lowest one was from Amhara region (Gojjam) [21]. The purpose of this review was to assess the pooled prevalence and associated factors of under-five anemia by reviewing the finding of available studies. The pooled prevalence of under-five anemia in Ethiopia was 44.83%. Anemia becomes a public health problem when the magnitude is above 5% of the population [29]. According to World Health Organization (WHO) classifications of anemia, it is severe, moderate, and mild when the prevalence is above 40, 20, 5%, respectively [29]. Thus, the level of under-five anemia in the current study was classified as severe. The findings of the current study is lower than studies done in Cape Verde, West Africa, 51.8% [30] and Tanzania, 84.6% [31]. This could be due to difference in practice of timely initiation of complementary feeding between Ethiopia and Tanzania. In Tanzania, about 84% of children were not exclusively breastfeed [31]. Hence, early introduction of complementary feeding before six-months-old like cow milk should not replace iron-rich foods and which may result in iron deficiency anemia [32].

This result is higher than studies done in China (22.4%) [33], Uganda (37.2%) [34], Colombia (27%) [35], and Denmark (13%) [35]. The possible explanation is in the current study area; there is a high prevalence of hookworm infestation, maternal and childhood malnutrition, malaria infection and a high number of low birth weight babies and stunted children. Additionally, it may be due to variations in socioeconomic status and infant feeding practices (such as exclusive breastfeeding and time of introductions of complementary feeding).

In subgroup analysis, the prevalence of anemia was higher among children under 2 years of age (50.3%) than for children 2–5 years of age (43.3%). This finding is supported by studies done in Ghana [36] and Eastern Cuba [37]. This may be because children born from malnourished mothers have poor stores of iron; infants are more susceptible to infections and diseases that result in poor absorption of iron [38]; the low concentration of iron in breast milk and the introduction of complementary foods often occurs at this age group results high prevalence of anemia compared with children 2–5 years of age.

The finding of this meta-analysis revealed that male under-five children had a higher prevalence of anemia (31.3%) than females (26.8%). This finding is similar to a study done in India [39], but not supported with a systematic analysis of the global anemia burden [40]. This difference could be due to it appears almost entirely driven by the excess prevalence of male anemia resulting from hookworm while excess anemia in females at other ages was related to iron deficiency. Therefore, children should be restricted to barefoot during playing and avoid playing with mud.

In this study, anemia is the major public health problem of the population. The contributing factors for under-five anemia were poor food diversity, food insecurity, stunting, and not dewormed. Children who fed less than four food groups per day were 1.71 times more likely to develop anemia than their counterparts. Similarly, food-insecured children were 2.87 times at high risk to develop anemia than secured ones. This finding is supported in studies done in Italy [41] and middle-income countries [42]. This could be due to children from food insecurity households lack nutritious diets that have high protein quality, adequate micronutrient content and bioavailability, macro-minerals, iron, and essential fatty acids that increase the likelihood of childhood anemia [43].

Children who were stunted were 2.54 times more likely had anemia compared with children who were not stunted. Additionally, children who were not receiving anti-helminthes were 2.34 times more likely to develop anemia than dewormed ones. This finding was consistent with studies done in Tanzania [44], Vietnam [45], Cambodia [46], and Northwest Uganda [47]. This is the general fact that stunting is a consequence of malnutrition and it is a significant risk factor for anemia. Similarly, helminths destroy red blood cells and decrease their lifespan, which is reaching in hemoglobin and finally results in anemia. Therefore, deworming infants every 6 months is the best option of the prevention mechanism of under-five anemia.

Limitation

Since it is the first systematic review and meta-analysis, it is taken as strength. Predictor variables were estimated by odd’s ratio and it may be affected by other confounding variables. This review has not registered online.

Conclusion

The pooled prevalence of under-five anemia was classified as severe. Therefore, supplementation and fortification programs of foods, periodic deworming, feeding diversified food, and secured food households are strongly recommended to alleviate under-five anemia.

Availability of data and materials

Data will be available upon request of the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- EDHS:

-

Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey

- Hb:

-

Hemoglobin

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

WHO. Haemoglobin concentrations for the diagnosis of anemia and assessment of severity. Vitamin and Mineral Nutrition Information System. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011.

Black RE, Victora CG, Walker SP, et al. Maternal and child under-nutrition and overweight in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet. 2013;382(9890):427–51.

Yang W, Li X, Li Y, et al. Anemia, malnutrition and their correlations with socio-demographic characteristics and feeding practices among infants aged 0–18 months in rural areas of Shaanxi province in northwestern China: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):1.

Allen LH, De Benoist B, Dary O, Hurrell R, World Health Organization. Guidelines on food fortification with micronutrients. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006.

Benoist B, McLean E, Egli I, Cogswell. Worldwide prevalence of anemia 1993-2005. eds. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2008. Available at http://www.whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2008/97 892415966 57eng.pdf Accessed 11th November 2018.

Central Statistical Agency (CSA) [Ethiopia] and ICF. 2016. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2016: key indicators report. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, and Rockville, Maryland, USA. CSA and ICF.

Gebreegziabiher G, Etana B, Niggusie D. Determinants of anemia among children aged 6–59 months living in Kilte Awulaelo Woreda. Anemia: Northern Ethiopia; 2014.

Woldie H, Kebede Y, Tariku A. Factors associated with anemia among children aged 6–23 months attending growth monitoring at Tsitsika Health Center. Northeast Ethiopia. Journal of nutrition and metabolism: Wag-Himra Zone; 2015.

Jemal Y, Haidar J, Makau WK. The magnitude and determinants of anaemia among refugee preschool children from the Kebribeyah refugee camp, Somali region, Ethiopia. South African Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2017;30(1):1–6.

Tiku YS, Mekonnen TC, Workie SB, Amare E. Does anaemia have major public health importance in children aged 6–59 months in the Duggina Fanigo District of Wolaita Zone, Southern Ethiopia. Annals of Nutrition and Metabolism. 2018;72(1):3–11.

Malako BG, Teshome MS, Belachew T. Anemia and associated factors among children aged 6–23 months in Damot Sore District, Wolaita Zone. South Ethiopia. BMC hematology. 2018;18(1):14.

Alemayehu MA, Meskele M, Alemayehu BA, Yakob B. Prevalence and correlates of anemia among children aged 6-23 months in Wolaita Zone. Southern Ethiopia. bioRxiv. 2018;441196.

Abdi Guled R, Mamat NM, Balachew T, Bakar MA, Azdie W, Assefa N. Predictors and prevalence of anemia, among children aged 6 to 59 months in shebelle zone, Somali region, eastern Ethiopia: A cross sectional study. International Journal of Development Research. 2017;7(1):11189–96.

Feleke BE. Maternal HIV status affects the infant hemoglobin level: a comparative cross-sectional study. Medicine. 2016; 95(31).

Gebreeziabher T, Stoecker BJ. Prevalence of anemia is significantly higher in six month old infants than in their mothers in southern Ethiopia. The FASEB Journal. 2017;31(1):786–16.

Muchie KF. Determinants of severity levels of anemia among children aged 6–59 months in Ethiopia: further analysis of the 2011 Ethiopian demographic and health survey. BMC Nutrition. 2016 Dec;2(1):51.

Kawo KN, Asfaw ZG, Yohannes N. Multilevel analysis of determinants of anemia prevalence among children aged 6–59 months in Ethiopia: classical and Bayesian approaches; 2018.

Kebede SW, Beyene DA, Meshesha AG, Sinishaw MA. Two thirds of hookworm infected children were anemic at the outpatient department in Jimma Health Center, Jimma, Southwest Ethiopia. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Disease. 2016;6(9):691–4.

Habte D, Asrat K, Magafu MG, Ali IM, Benti T, Abtew W, Tegegne G, Abera D, Shiferaw S. Maternal risk factors for childhood anaemia in Ethiopia. African Journal of Reproductive Health. 2013;17(3):110–8.

Yeshimebet G/Selassie. Magnitude, severity and associated factors of anemia among under-five children attending Hawassa University Teaching and Referral Hospital and Adare Hospital in Hawassa, Southern Ethiopia, 2016. Retrieved from: URI: http://localhost:80/xmlui/handle/123456789/6046 (Nov, 15, 2018).

Gashu D, Stoecker BJ, Adish A, Haki GD, Bougma K, Marquis GS. Ethiopian pre-school children consuming a predominantly unrefined plant-based diet have low prevalence of iron-deficiency anaemia. Public health nutrition. 2016;19(10):1834–41.

Melku M, Alene KA, Terefe B, Enawgaw B, Biadgo B, Abebe M, Muchie KF, Kebede A, Melak T, Melku T. Anemia severity among children aged 6–59 months in Gondar town, Ethiopia: a community-based cross-sectional study. Italian journal of pediatrics. 2018;44(1):107.

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2009;62(10):e1–34.

Newcastle-Ottawa Scale customized for cross-sectional studies. In. available from https://static-content.springer.com/esm/.../12889_2012_5111_MOESM3_ESM.doc.

Rücker G, Schwarzer G, Carpenter JR, Schumacher M. Undue reliance on I2 in assessing heterogeneity may mislead. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8:79.

Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins J, Rothstein HR. A basic introduction to fixed-effect and random-effects models for meta-analysis. Research Synthesis Methods. 2010;1(2):97–111.

Gari T, Loha E, Deressa W, Solomon T, Atsbeha H, Assegid M, Hailu A, Lindtjørn B. Anaemia among children in a drought affected community in south-central Ethiopia. PloS one. 2017;12(3):e0170898.

Hoy D, Brooks P, Woolf A, Blyth F, March L, Bain C, et al. Assessing risk of bias in prevalence studies: modification of an existing tool and evidence of interrater agreement. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2012;65(9):934–9.

WHO . The global prevalence of anemia in 2011. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015.

Semedo RM, Santos MM, Baião MR, Luiz RR, da Veiga GV. Prevalence of anaemia and associated factors among children below five years of age in Cape Verde. West Africa. J Health Popul Nutr. 2014;32(4):646–57.

Kejo D, Petrucka PM, Martin H, Kimanya ME, Mosha TC. Prevalence and predictors of anemia among children under 5 years of age in Arusha District ,Tanzania. Pediatric Health Med Ther. 2018;9:9–15.

Hallberg L, Rossander-Hultén L, Brune M, Gleerup A. Bioavailability in man of iron in human milk and cow’s milk in relation to their calciumcontents. PediatrRes. 1992;31(5):524–7.

Zhao A, Zhang Y, Peng Y, et al. Prevalence of anemia and its risk factors among children 6-36 months old in Burma. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2012;87(2):306–11.

Legason ID, Atiku A, Ssenyonga R, Olupot-Olupot P, Barugahare JB. Prevalence of anaemia and associated risk factors among children in North-western Uganda: a cross sectional study. BMC Hematol. 2017;17:10.

World Health Organization. World Health Organization, Global Health Observatory Data Repository/World Health Statistics. Availabe at: apps.who.int/gho/data/node.main. lang = en .(Retrieved from November, 2018).

Ewusie JE, Ahiadeke C, Beyene J, Hamid JS. Prevalence of anemia among under-5 children in the Ghanaian population: estimates from the Ghana demographic and health survey. BMC public health. 2014 Dec;14(1):626.

Pita Rodríguez GM, Jiménez Acosta S, Basabe Tuero B, García Roche RG, Macías Matos C, Selva Suárez L, Hernández Fernández C, Cruz Jorge M, Herrera Charro R. O Farrill López R, Calderius Espinosa I. Anemia in children under five years old in Eastern Cuba, 2005–2011. Medicc Review. 2014;16(1):16–23.

Osório MM, Lira PI, Batista-Filho M, Ashworth A. Prevalence of anemia in children 6-59 months old in the state of Pernambuco. Brazil. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2001;10(2):101–7.

Pasricha SR, Black J, Muthayya S, Shet A, Bhat V, Nagaraj S, Prashanth NS, Sudarshan H, Biggs BA, Shet AS. Determinants of anemia among young children in rural India. Pediatrics. 2010: peds-2009.

Kassebaum NJ, Jasrasaria R, Naghavi M, Wulf SK, Johns N, Lozano R, Regan M, Weatherall D, Chou DP, Eisele TP, Flaxman SR. A systematic analysis of global anemia burden from 1990 to 2010. Blood. 2014;123(5):615–24.

De Pee S, Bloem MW. Current and potential role of specially formulated foods and food supplements for preventing malnutrition among 6-to 23-month-old children and for treating moderate malnutrition among 6-to 59-month-old children. Food and nutrition bulletin. 2009; 30(3_suppl3):S434-63.

Pasricha SR, Drakesmith H, Black J, Hipgrave D, Biggs BA. Control of iron deficiency anemia in low-and middle-income countries. Blood. 2013;121(14):2607–17.

Parlesak A, Geelhoed D, Robertson A. Toward the prevention of childhood under-nutrition: diet diversity strategies using locally produced food can overcome gaps in nutrient supply. Food and nutrition bulletin. 2014;35(2):191–9.

Guyatt HL, Brooker S, Kihamia CM, Hall A, Bundy DA. Evaluation of efficacy of school-based anthelmintic treatments against anaemia in children in the United Republic of Tanzania. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2001;79:695–703.

Hieu NT, Sandalinas F, de Sesmaisons A, Laillou A, Tam NP, Khan NC, Bruyeron O, Wieringa FT, Berger J. Multi-micronutrient-fortified biscuits decreased the prevalence of anaemia and improved iron status, whereas weekly iron supplementation only improved iron status in Vietnamese school children. British Journal of Nutrition. 2012;108(8):1419–27.

Perignon M, Fiorentino M, Kuong K, Burja K, Parker M, Sisokhom S, Chamnan C, Berger J, Wieringa FT. Stunting, poor iron status and parasite infection are significant risk factors for lower cognitive performance in Cambodian school-aged children. PloS one. 2014;9(11):e112605.

Legason ID, Atiku A, Ssenyonga R, Olupot-Olupot P, Barugahare JB. Prevalence of anaemia and associated risk factors among children in North-western Uganda: a cross sectional study. BMC hematology. 2017 Dec;17(1):10.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable

Consent to publication

Not applicable.

Funding

No funding was obtained for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AB was responsible for the conception of research protocol, study design, literature review, data extraction, data analysis, interpretation, and drafting the manuscript. TT was responsible for the data analysis and reviewing the manuscript. AB and TT were responsible for the data extraction and quality assessment. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors have declared that they have no competing interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Belachew, A., Tewabe, T. Under-five anemia and its associated factors with dietary diversity, food security, stunted, and deworming in Ethiopia: systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst Rev 9, 31 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-020-01289-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-020-01289-7