Abstract

Background

There is no consensus on the definition of poor growth response after the first year of growth hormone (GH) treatment. We determined the proportion of poor responders identified by different criteria in children with GH deficiency (GHD) and born small for gestational age (SGA). The second aim was to analyze the IGF-1 response in poor growth responders.

Methods

First-year height data of 171 SGA and 122 GHD children who remained prepubertal during the first GH treatment year were retrieved from the BESPEED database and analyzed. Criteria for poor first-year response/responsiveness were: change in height (∆Ht) SDS<0.3 or<0.5, height velocity (HV) SDS<0.5 or <1 based on the population reference, HV SDS<− 1 based on the KIGS expected HV curve (HV Ranke SDS), studentized residual (SR) <− 1 in the KIGS first-year prediction model.

Results

∆Ht SDS<0.5 gave the highest percentage poor responders (37% SGA, 26% GHD). Although % poor responders were comparable for ∆Ht SDS<0.3, HV SDS<+ 0.5, HV SDS<+ 1, SR<− 1, and HV Ranke SDS<− 1, these criteria did not always identify the same patients as poor responders. Among the poor growth responders 24% SGA and 14% GHD patients had an IGF-1 increase < 40%.

Conclusions

The different response criteria yield high but comparable percentages poor responders, but identify different patients. This study does not provide evidence that one criterion is better than another. A limited IGF-1 generation is not the major reason for a poor growth response in the first year of GH treatment in SGA and GHD children.

Trial registration

Retrospectively registered.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Growth hormone (GH) deficiency (GHD) and short stature as a consequence of a small size at birth (SGA) are the most frequent indications for GH therapy in children in Europe. Although in general a substantial fraction of the height deficit is already recovered during the first year of GH treatment in these growth disorders, a high proportion has a poor growth response in the first year of GH therapy [1]. This first year growth response is paramount since it is the major determinant of the gain during the subsequent treatment years and correlates with the final height outcome [2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12].

Traditionally the growth response during the first year of GH treatment is evaluated by auxological parameters, such as the gain in height SDS (∆Ht SDS), the observed height velocity (HV) expressed in cm/year or in SDS, or the increase in HV (∆HV) compared to the pre-treatment year [13]. A number of definitions of poor first-year growth response have been proposed in clinical trials and consensus statements, such as a gain in height <0.3 SD or <0.5 SD, a first-year HV <+ 0.5 SD or <+ 1.0 SD for age and gender, or an increase in HV <3 cm/year compared to the pretreatment year [14].

Another more recent method to evaluate the growth promoting efficacy of GH treatment in short children is to compare the observed to the expected growth response defined by certain patient and treatment characteristics, which has been defined as responsiveness, reflecting the ability of an individual person to respond to GH [11, 12, 15]. First year height velocity response curves, determined by age, treatment indication and sometimes gender (Bakker et al. [16], Ranke et al. [13], and Straetemans et al. [17]) have been published. A height velocity below − 1.0 SD on the growth response curve has been considered as a poor response.

In an attempt to include even more parameters to determine the responsiveness to GH, Ranke et al. have derived prediction models for the first year response to GH in various treatment indications. They include among other factors birth weight, GH dose and parental heights [18,19,20]. Responsiveness is expressed as a studentized residual [SR = (observed HV – predicted HV)/SD of the predicted HV] and a SR <− 1 has been considered a poor response [12]. This implies that 16.5% of the patients are poor responders. Although these multivariate prediction models provide a more individualized response target, some patients meet their very poor prediction and are therefore not considered poor responders despite their poor absolute response.

Several conditions might explain a poor growth response to GH administration. With the exception of a poorly responsive growth plate, most conditions such as poor compliance, a hidden chronic disease or a partial GH insensitivity due to abnormalities in the GH-IGF-1 axis will limit a sufficient generation of IGF-1 during GH administration. Different patterns of IGF-1 increase during GH treatment between children with GHD, SGA children and other disorders have been described previously [21, 22]. However, up to now, there have been no previous reports comparing the commonly used measures of poor growth response with measures of poor responsiveness from prediction models and only limited data are available on the IGF-1 increase during GH treatment in relation to the growth response in short GHD and SGA children.

We therefore compared the first year growth response and responsiveness criteria in prepubertal children with SGA and GHD, registered in the database of the BElgian Society for PEdiatric Endocrinology and Diabetology (BESPEED). We expected a lower percentage of poor responders using more individualized growth response targets, especially in the SGA group, where GH sensitivity and treatment modalities are more variable. In addition, we evaluated the IGF-1 response during the first year of GH treatment in those children with a poor growth response.

Methods

Subjects

The auxological data and first year treatment characteristics of prepubertal children diagnosed with SGA and non-acquired GHD, who had been treated exclusively with recombinant human GH on a daily basis, were retrieved from the Belgian Registry of children treated with GH (BELGROW), which is administrated by BESPEED since 1985. The Registry stores coded data and informed consent was secured prior to data entry. Data of patients who started GH treatment between January 2003 and May 2010 were analyzed.

Diagnosis of SGA or GHD was made by the treating physician after peer-review by the other BESPEED members. All GHD patients had a peak GH concentration ≤ 10 μg/L in two provocation tests (glucagon and insulin test). Priming before testing with respectively estrogen and testosterone was done routinely in girls ≥8 years old and boys ≥9 years old. GHD patients with and without developmental anatomical anomalies of the pituitary were included. Patients with acquired GHD were excluded. Severe GHD was defined as a peak GH response less than 5 μg/L in both provocation tests. Included SGA children had a birth weight and/or birth length < − 2 SD [23] and a height < − 2.5 SD at the age of 4 years and at onset of therapy. Prepuberty was defined as having a testicular volume less than 4 ml for boys and Tanner breast stage 1 for girls.

In the GHD group, patients born SGA were excluded. In the SGA group, patients with severe GHD (peak GH < 5 μg/L) were also excluded. Additional exclusion criteria for all groups were: age ≥10 years for girls and ≥12 years for boys at the end of the first year of GH treatment, gestational age <30 weeks, any chronic disease or genetic syndrome interfering with a normal growth potential, a known poor adherence to GH treatment, concomitant treatment with steroids > 12 mg/m2.day (hydrocortisone equivalent), additional previous or current growth promoting therapy such as sex steroids, oxandrolone or aromatase inhibitors. Only patients who remained prepubertal during the first treatment year were considered for analysis.

Methods

Variables retrieved from the register were (a) status at birth: gender, birth weight and length; (b) genetic background: mother’s height (Ht), father’s Ht; (c) patient variables at the start of the treatment period: chronological age, Ht, weight (Wt), the highest peak GH concentration in GH provocation tests; (d) first year GH treatment modality: average GH dose (μg/kg.day) during the first year of GH treatment; (e) Ht, Wt after 1 year of GH treatment. IGF-1 values (ng/mL) before the start and during the first year GH treatment were retrieved from the medical files.

Birth weight for gestational age was transformed into SDS, based on the standards of Niklasson et al. [23]. The midparental height (MPH) was calculated as follows: [father’s Ht (cm) + mother’s Ht (cm) + 13 for boys/− 13 for girls]/2 [24]. Height, weight, body mass index (BMI), HV, and MPH were converted to SDS using Belgian reference data by Roelants et al. [25].

First-year gain in height (∆Ht) SDS and first-year height velocity (HV) (cm/year), were calculated as the increment in height between start of treatment and a measurement made after minimum 9 months and maximum 15 months of GH treatment, subsequently scaled to 12 months.

The observed first-year HV (cm/yr) was expressed as SDS, either using the Flemish HV reference curve [25] or using the reference curves for GH treated prepubertal GHD and SGA children developed by Ranke et al. based on the KIGS database [13]. The latter was calculated as follows: the HV of the child in cm/year minus the mean HV for age and diagnosis divided by the SD for age and diagnosis.

Predicted first-year HV (cm/year) was calculated with the KIGS first-year prediction models for GHD (GH peak included) [18, 19] and SGA [20], provided that all parameters required for the mathematical algorithm were available. These prediction models are available on the Prediction Models Web [26] and on the iGRO website [27]. Differences between observed and predicted HVs were expressed as studentized residuals (SR). SRs were calculated as the observed HV minus the predicted HV, divided by the SD of the predicted HV of the child. SR is the index of responsiveness (IoR), thus the index of an individual’s actual growth versus its unique predicted growth.

The criteria used to define a poor first-year growth response were: (a) ∆ Ht < 0.3 SD [28], (b) ∆ Ht < 0.5 SD [13], (c) HV < + 0.5 SD on the population HV reference curves [25], (d) HV < + 1.0 SD on the population HV reference curves [25], (e) observed first-year HV more than 1 SD below the patient’s predicted first-year height velocity (SR < − 1) [12], and (f) HV < − 1.0 SD for expected first-year height velocity based on diagnosis specific reference data developed by Ranke et al. (HV Ranke SDS) [13].

The patients were divided into three response groups: poor response to all criteria, questionable response (poor response to at least 1 criterion), and good response to all criteria.

The percentage increase in IGF-1 was calculated using the IGF-1 value before the start of GH treatment and the highest IGF-1 value during the first year of GH treatment. A poor IGF-1 response during the first year of GH treatment was defined as an increase of less than 40% after at least 3 months of GH therapy. This cutoff value corresponds to the 10th percentile of IGF-1 increase in GHD patients [29].

Statistical analysis

The variables were tested for normality with the one-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and are reported as medians (25–75 percentile) or means (± SD). Student’s t test, one-way ANOVA and Bonferroni correction were used to test for differences between groups when the distribution of data was normal. Otherwise Mann-Whitney-U and Kruskal-Wallis tests were applied. Simple linear correlation analysis was conducted using the Spearman formula. Statistical significance was set at the 5% level (p < 0.05). IBM SPSS statistics 21® software was used for all statistical analyses. The patient population was of sufficient size to detect a 50% lower percentage poor responders for the criterion SR < − 1 compared to the criterion HV < + 1.0 SD (α = 0.05 and 1-β = 0.8).

Results

Baseline characteristics

In total, 171 SGA patients and 122 GHD patients met the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Sixty six children were diagnosed with severe GHD (peak GH < 5 μg/L). Baseline auxological characteristics at the start of GH treatment are listed in Table 1. For both groups there was a predominance of males (64–66%). Boys started GH treatment at a significantly older age than girls (7.5 vs. 6.6 years, respectively; p = 0.01); 26 (=15%) SGA and 19 (=16%) GHD boys were older than 10 years at the start of treatment. At baseline, there was no significant difference in median Ht SDS between SGA and GHD patients (SGA: − 3.06 SD, GHD: − 3.20 SD). The mean average GH dose during the first year of GH treatment for patients with GHD was 26.9 μg/kg*day, which was significantly lower than the dose for patients with SGA (38.1 μg/kg*day; p < 0.001). Children born SGA had a lower weight and BMI at start than children with GHD (p < 0.001). Children with GHD had the largest difference between height SDS at start and MPH SDS.

Response and responsiveness after the first year of GH treatment

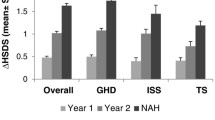

As shown in Table 2, children with GHD had a significantly greater increase in Ht SDS and HV than children with SGA (p < 0.001). In the SGA group the mean observed HV is close to the expected HV. In contrast, GHD responded slightly worse than predicted (SR − 0.35 ± 1.13; p = 0.05).

Children with severe GHD (max. GH peak < 5 μg/L) had a greater increase in Ht SDS (0.97 ± 0.65 vs 0.62 ± 0.42; p = 0.001), and a greater HV (cm/yr) (10.1 ± 2.8 vs. 8.4 ± 1.9; p < 0.001) than the group with less-severe GHD.

There was no significant difference in ∆Ht SDS, nor in HV (cm/yr) between SGA children with only a low birth weight (n = 24) and SGA children with only a low birth length (n = 38).

Comparison of poor response and poor responsiveness criteria

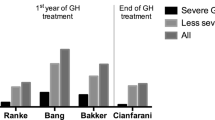

One hundred and six (106) patients (=36%) met at least one of the proposed criteria for poor response. Figure 1 shows the percentage of patients labeled as poor responders according to the different criteria. ∆Ht < 0.5 SD gave the highest proportion of poor responders (37% in SGA, 26% in GHD). ∆Ht < 0.3 SD generated 15% poor responders in SGA and 12% in GHD. HV < 0.5 SD was seen in 17% of SGA and in 11% of GHD patients. HV < 1.0 SD was observed in 25% of SGA and 19% of GHD subjects. Eighteen percent of patients with SGA and 20% of patients with GHD had an observed first-year HV more than 1 SD below the predicted first-year height velocity (SR < − 1). Fourteen percent of patients with SGA and 12% of patients with GHD had a HV < − 1.0 SD for expected first-year HV based on diagnosis specific reference data developed by Ranke et al. (HV Ranke SDS < − 1).

Percentage of poor growth responders after first-year GH treatment in prepubertal children according to various criteria in SGA and GHD patients. SGA = small for gestational age; GHD = growth hormone deficiency; SDS = standard deviation score; ∆Ht = first-year gain in height; HV = height velocity; SR = studentized residual. * HV < − 1 SD for expected first-year treatment response based on reference data developed by Ranke et al. # p < 0,01 vs. ∆Ht SDS < 0.3, HV SDS < 0.5, SR < − 1, HV Ranke SDS < − 1; @ p < 0,05 vs. ∆Ht SDS < 0.3, HV SDS < 0.5, HV Ranke SDS < − 1

Between the SGA and GHD group there were no significant differences in percentages of poor responders. In the SGA group, the percentage of poor responders for the ∆Ht < 0.5 SD criterion was significantly different from those for the ∆Ht < 0.3 SD, HV < + 0.5 SD, SR < − 1 and HV Ranke <− 1 SD criteria (p < 0.01). In the GHD group, the percentage of poor responders for the ∆Ht < 0.5 SD criterion was significantly different from those for the ∆Ht < 0.3 SD, HV < + 0.5 SD and HV Ranke <− 1 SD criteria (p < 0.05).

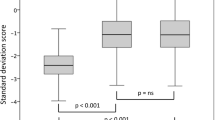

Although the percentages of poor responders were comparable for the criteria ∆Ht < 0.3 SD, HV < + 0.5 SD, HV < + 1 SD, SR < − 1, and HV Ranke <− 1 SD in the SGA and GHD group, these specific criteria did not always identify the same patients as poor responders, as shown in Fig. 2. For example, for the criteria ∆Ht < 0.3 SD, HV < + 1 SD and SR < − 1, only 17/45 SGA patients and 7/30 GHD patients were identified as poor responders by all three criteria. For the criteria HV < + 1 SD and SR < − 1, respectively 22/45 and 11/30 patients in the SGA and GHD group were identified by both criteria as poor responders.

Number of poor responders for SGA patients (bold) and GHD patients (italic). SGA = small for gestational age; GHD = growth hormone deficiency; SDS = standard deviation score; ∆Ht = first-year gain in height; HV = height velocity; SR = studentized residual. * HV < − 1 SD for expected first-year treatment response based on reference data developed by Ranke et al.

Poor response to all criteria was observed in 16 (10%) SGA and 7 (7%) GHD patients, questionable response (poor response to at least one criterion) in 49 (30%) SGA and 34 (32%) GHD patients, and good response to all criteria in 96 (60%) SGA and 64 (61%) GHD patients. In the SGA group, age was significantly older in the group with questionable response compared to the group with good response (data not shown). There were no other significant differences between the responder groups in the SGA group. In the GHD group, father height SDS was significantly lower and ∆ BMI SDS was significantly higher in the group with questionable response compared to the group with good response. There were no other significant differences between the responder groups. IGF-1 could not be compared because this parameter was available in only a minority of the patients (data not shown).

IGF-1 response of poor growth responders

Out of the 106 patients who showed a poor growth response for at least one criterion, 70 patients had results of at least two IGF-1 determinations available. There were no significant differences in the growth responses between poor responders with and without available IGF-1 values. For SGA (n = 41) and GHD (n = 29) patients with a poor first year growth response, the mean increase in IGF-1 was 126% (±126) and 176% (±193), respectively.

Ten (24%) SGA and 4 (14%) GHD patients had less than 40% increase in IGF-1 during the first year of GH treatment. GHD patients with blunted IGF-1 increase had a significantly lower BMI SDS at start compared to those with a normal increase (− 1.35 SD vs − 0.21 SD; p < 0.01) and had mothers with a taller height (0.66 SD vs − 1.02 SD; p < 0.01), while no differences in the available auxological parameters were found between SGA children with a poor and a normal IGF-1 increase.

Discussion

Depending on the criteria used, between 11 and 26% of short prepubertal GHD children, treated with a mean GH dose of 27 mcg/kg*d and between 14 and 37% of short prepubertal SGA children, treated with a mean GH dose of 38 mcg/kg*d, were found to be poor responders. ∆Ht > 0.5 SD was the most stringent criterion: 26% of GHD and 37% of SGA patients treated in Belgium did not meet this response criterion, whereas the HV Ranke SDS < − 1 gave the lowest percentages (12 and 14%).

Our prevalence results are comparable to the findings of Bang et al. [1] who also assessed the criteria for poor growth response in a group of 173 GHD and 54 SGA short prepubertal children from the Nordic countries. Beside the inclusion of SGA born children within the GHD group, the in- and exclusion criteria of this Nordic study are comparable to the data in our Belgian registry study, explaining to a great extend the similar proportion of poor responders.

Bang et al. [30] have argued that the response to GH should be clinically meaningful, implicating that treatment should diminish rapidly the height difference with peers, implicating a gain in height SDS of at least 0.5 SD during the first year. This criterion is based on the observation that the year to year change in height SDS in normal growing children can go up to 0.3 SD [31]. So to attribute the growth response to GH, the change in height SDS should be at least higher than 0.3 SD. However, since the gain in height SDS is age and diagnosis dependent [1, 16], a fixed cutoff will favor a better response in younger children and in severe GHD.

Comparing the annualized HV during the first year on GH with the HV of the pre-treatment year (∆HV, cm/year) might give an approximation of the GH induced HV, except in case a severely HV declining in the pretreatment year is present, as often seen in severe GHD. Theoretically, ∆HV (cm/year) may be the best response parameter to evaluate, however reliable pretreatment height measurements are often unavailable, as was the case in our database.

HV (cm/year) during the first year on GH treatment is highly age dependent [1, 16]. To express HV independent of age and in relation to normal gender related reference values, an SDS for age can be calculated. However, references are usually based on longitudinal studies with relatively small sample sizes or on cross-sectional data.

The ability of an individual patient to respond to GH (the responsiveness) should always be determined in order to evaluate the growth response correctly. For example, a patient with a first-year ∆Ht of 0.7 SD would be considered a good responder, but with a SR of, for example, − 1.2 this patient proves to have an inadequate response. A weakness of prediction models may be the lack of available patient characteristics needed to calculate responsiveness.

We hypothesized that a more individualized responsiveness criterion would yield 50% less poor responders than the more general response criteria. This hypothesis must be rejected because ∆Ht < 0.3 SD, HV < + 0.5 SD, HV < + 1 SD, SR < − 1 and HV Ranke SDS < − 1 SD gave the same proportion of poor responders in both treatment indications, although the GH doses are significantly different in both diagnostic groups. This supports the notion that there exists a continuum and overlap between partial GHD and SGA children without a postnatal catch up growth [32].

Although most criteria resulted in the same proportion of poor responders they did not identify the same patients. For example, HV < + 1 SD, the reimbursement response criterion of the European Medicines Agency (EMA) for GH treatment in short SGA children, generated a comparable amount of poor responders as the criterion SR < − 1 (respectively 25 and 18%). However, only 17 out of 45 of these poor responders fulfilled both criteria. Hence, these parameters cannot be used interchangeably. The fact that there is no concordance between the groups defined by the different criteria is interesting, but not surprising, since the response variables are principally different from the responsiveness parameters .

The long-term evaluation of response to GH has been validated for the KIGS prediction models by showing that SR is the second most important predictor of adult height after GH treatment. All the other proposed criteria for a poor first-year response have not been evaluated for their ability to predict a poor adult height outcome.

In our study, respectively 24 and 14% of the poor responders in the SGA and GHD group were found to have an insufficient IGF-1 increase in the first year. GH insensitivity is hence not a major reason for poor growth response in these children. GHD patients with low IGF-1 increase had a significantly lower BMI SDS at start compared to those with a normal increase. Nutritional constraints are possibly an important cause for the poor IGF-1 response. These children do not have sufficient calories to be able to grow, which may explain the poor growth response. Poor compliance is another possible reason for the poor IGF-1 response and growth response. Because IGF-I rises within days after GH administration, a normal IGF-I measurement cannot rule out poor adherence up to a week before the blood collection.

A weakness of this study is the limited amount of available IGF-1 values. However, no significant differences in the growth responses between poor responders with and without available IGF-1 values were observed.

IGF-1 levels after GH might fluctuate with the duration of GH therapy [1]. We therefore have chosen to take the maximum level into account and not a level at fixed duration. To circumvent the problem of non-centralized determination of IGF-1, the percentage increase was calculated on IGF-I levels determined in the same laboratory.

Conclusions

In conclusion, with the exception of the ∆Ht < 0.5 SD cutoff, the tested criteria resulted in the same proportion of poor growth responders in GH treated SGA and GHD patients, but did not always identify the same patients as poor responders. This study does not provide evidence that one criterion is better than another. A critical evaluation of these response parameters and their cutoff values with respect to their capacity to detect a poor final adult height outcome is needed to define the best poor response parameter. A limited capacity in IGF-1 generation did not appear to be a major reason for a poor growth response in both GHD as SGA children.

Abbreviations

- ∆Ht:

-

Change in height

- ∆HV:

-

Change in height velocity

- BESPEED:

-

BElgian Society for PEdiatric Endocrinology and Diabetology

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- EMA:

-

European Medicines Agency

- GH:

-

Growth hormone

- GHD:

-

Growth hormone deficiency

- Ht:

-

Height

- HV:

-

Height velocity

- IoR:

-

Index of responsiveness

- MPH:

-

Midparental height

- SDS:

-

Standard deviation score

- SGA:

-

Small for gestational age

- SR:

-

Studentized residual

- Wt:

-

Weight

References

Bang P, Bjerknes R, Dahlgren J, Dunkel L, Gustafsson J, Juul A, et al. A comparison of different definitions of growth response in short prepubertal children treated with growth hormone. Horm Res Paediatr. 2011;75(5):335–45.

Cutfield. Growth hormone treatment to final height in idiopathic growth hormone deficiency: the KIGS experience. In: Ranke MB, Price DA, Reiter EO, editors. Growth hormone therapy in pediatrics – 20 years of KIGS. Basel: Karger; 2007. p. 145–62.

Thomas M, Massa G, Bourguignon JP, Craen M, De Schepper J, de Zegher F, et al. Final height in children with idiopathic growth hormone deficiency treated with recombinant human growth hormone: the Belgian experience. Horm Res. 2001;55(2):88–94.

Carel JC, Ecosse E, Nicolino M, Tauber M, Leger J, Cabrol S, et al. Adult height after long term treatment with recombinant growth hormone for idiopathic isolated growth hormone deficiency: observational follow up study of the French population based registry. BMJ. 2002;325(7355):70.

Reiter EO, Price DA, Wilton P, Albertsson-Wikland K, Ranke MB. Effect of growth hormone (GH) treatment on the near-final height of 1258 patients with idiopathic GH deficiency: analysis of a large international database. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91(6):2047–54.

de Ridder MA, Stijnen T, Hokken-Koelega AC. Prediction of adult height in growth-hormone-treated children with growth hormone deficiency. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92(3):925–31.

August GP, Julius JR, Blethen SL. Adult height in children with growth hormone deficiency who are treated with biosynthetic growth hormone: the National Cooperative Growth Study experience. Pediatrics. 1998;102(2 Pt 3):512–6.

Carrascosa A, Audi L, Fernandez-Cancio M, Yeste D, Gussinye M, Campos A, et al. Height gain at adult-height age in 184 short patients treated with growth hormone from prepubertal age to near adult-height age is not related to GH secretory status at GH therapy onset. Horm Res Paediatr. 2013;79:145–56.

Rachmiel M, Rota V, Atenafu E, Daneman D, Hamilton J. Final height in children with idiopathic growth hormone deficiency treated with a fixed dose of recombinant growth hormone. Horm Res. 2007;68(5):236–43.

Kristrom B, Dahlgren J, Niklasson A, Nierop AF, Albertsson-Wikland K. The first-year growth response to growth hormone treatment predicts the long-term prepubertal growth response in children. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2009;9:1.

Wit JM, Ranke MB, Albertsson-Wikland K, Carrascosa A, Rosenfeld RG, Van Buuren S, et al. Personalized approach to growth hormone treatment: clinical use of growth prediction models. Horm Res Paediatr. 2013;79(5):257–70.

Ranke MB, Lindberg A, Mullis PE, Geffner ME, Tanaka T, Cutfield WS, et al. Towards optimal treatment with growth hormone in short children and adolescents: evidence and theses. Horm Res Paediatr. 2013;79(2):51–67.

Ranke MB, Lindberg A. Observed and predicted growth responses in prepubertal children with growth disorders: guidance of growth hormone treatment by empirical variables. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(3):1229–37.

Patel. Predicting response to growth hormone treatment. Indian J Pediatr. 2012;79(2):229–37.

Ranke. Predicting growth in response to growth hormone treatment. Growth Hormon IGF Res. 2009;19:1–11.

Bakker B, Frane J, Anhalt H, Lippe B, Rosenfeld RG. Height velocity targets from the national cooperative growth study for first-year growth hormone responses in short children. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(2):352–7.

Straetemans S, Roelants M, Thomas M, Rooman R, De Schepper J. Reference curve for the first-year growth response to growth hormone treatment in prepubertal children with idiopathic growth hormone deficiency: validation of the KIGS first-year growth response curve using the Belgian register for the study of growth and puberty problems. Horm Res Paediatr. 2014;81(5):343–9.

Ranke MB, Lindberg A, Chatelain P, Wilton P, Cutfield W, Albertsson-Wikland K, et al. Derivation and validation of a mathematical model for predicting the response to exogenous recombinant human growth hormone (GH) in prepubertal children with idiopathic GH deficiency. KIGS International Board. Kabi Pharmacia International Growth Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84(4):1174–83.

Ranke MB, Lindberg A, Albertsson-Wikland K, Wilton P, Price DA, Reiter EO. Increased response, but lower responsiveness, to growth hormone (GH) in very young children (aged 0-3 years) with idiopathic GH deficiency: analysis of data from KIGS. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(4):1966–71.

Ranke. Prediction of response to growth hormone treatment in short childen born small for gestational age: analysis of data from KIGS (Pharmacia international growth database). J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:125–31.

Ranke MB, Traunecker R, Martin DD, Schweizer R, Schwarze CP, Wollmann HA, et al. IGF-I and IGF binding protein-3 levels during initial GH dosage step-up are indicators of GH sensitivity in GH-deficient children and short children born small for gestational age. Horm Res. 2005;64(2):68–76.

Tillmann V, Patel L, Gill MS, Whatmore AJ, Price DA, Kibirige MS, et al. Monitoring serum insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I), IGF binding protein-3 (IGFBP-3), IGF-I/IGFBP-3 molar ratio and leptin during growth hormone treatment for disordered growth. Clin Endocrinol. 2000;53(3):329–36.

Niklasson A, Ericson A, Fryer JG, Karlberg J, Lawrence C, Karlberg P. An update of the Swedish reference standards for weight, length and head circumference at birth for given gestational age (1977–1981). Acta Paediatr Scand. 1991;80(8–9):756–62.

Cole TJ. Some questions about how growth standards are used. Horm Res. 1996;45(Suppl 2):18–23.

Roelants M, Hauspie R, Hoppenbrouwers K. References for growth and pubertal development from birth to 21 years in Flanders, Belgium. Ann Hum Biol. 2009;36(6):680–94.

Ranke MB. Prediction Models Web. http://www.growthpredictions.org.

Individual Growth Response Optimisation (iGRO). https://igro-gh.com/.

Cohen P, Rogol AD, Deal CL, Saenger P, Reiter EO, Ross JL, et al. Consensus statement on the diagnosis and treatment of children with idiopathic short stature: a summary of the growth hormone research society, the Lawson Wilkins Pediatric Endocrine Society, and the European Society for Paediatric Endocrinology Workshop. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(11):4210–7.

Ranke. Insulin-like growth factor 1 levels in patients within the KIGS database. Growth hormone therapy in pediatrics – 20 years of KIGS. Basel: Karger; 2007. p. 83–92.

Bang P, Ahmed SF, Argente J, Backeljauw P, Bettendorf M, Bona G, et al. Identification and management of poor response to growth-promoting therapy in children with short stature. Clin Endocrinol. 2012;77(2):169–81.

Karlberg J, Fryer JG, Engstrom I, Karlberg P. Analysis of linear growth using a mathematical model. II. From 3 to 21 years of age. Acta Paediatr Scand Suppl. 1987;337:12–29.

Savage. The continuum of growth hormone–IGF-I axis defects causing short stature: diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. Clin Endocrinol. 2010;72:721–8.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Christine Derycke and Franciska Verlinde for their help in data collection. In addition to the authors, the following investigators are members of BESPEED and contributed to the Belgian Registry of children treated with GH (BELGROW): A. France, H. Dotremont, M. Den Brinker (University Hospital Antwerp), M. Cools, K. De Waele, S. Van Aken, S. van der Straaten (University Hospital Ghent), I. Gies, J. Vanbesien (University Hospital Brussels), J.P. Bourguignon, M.C. Lebrethon, A.S. Parent (University Hospital Liège), C. Heinrichs, S. Tenoutasse, C. Brachet, E. Boros (University Children’s Hospital HUDE, Brussels), M. Maes, V. Beauloye, P Lysy (University Hospital Saint-Luc, Brussels), G. Massa, R. Zeevaert (Jessa Hospital, Hasselt), F. de Zegher, I. Francois, D. Beckers, M. Van Helvoirt, K. Casteels (University Hospital Leuven), D. Beckers, T. Mouraux (CHU UCL Mont Godinne), K. Logghe (Delta Hospital Roeselare), G. Thiry-Counson (Clinique Saint-Joseph Liège), O. Chivu (CHC Espérance, Montegnée), S. Depoorter (AZ St. Jan Brugge). This study was supported by a research grant from the Belgian Society for Pediatric Endocrinology and Diabetology (BESPEED).

Funding

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

SS, RR, and JDS conceived and designed research. MT made substantial contributions to acquisition of data. SS, RR, and JDS analyzed and interpreted the data. SS, RR, and JDS wrote the manuscript. MT and MC were involved in critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. All the authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this submitted manuscript and approved submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The data were retrieved from the Belgian Registry of children treated with GH (BELGROW), which is administrated by BESPEED since 1985. The Registry stores coded data and informed consent was secured prior to data entry.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Straetemans, S., Thomas, M., Craen, M. et al. Poor growth response during the first year of growth hormone treatment in short prepubertal children with growth hormone deficiency and born small for gestational age: a comparison of different criteria. Int J Pediatr Endocrinol 2018, 9 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13633-018-0064-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13633-018-0064-3