Abstract

Background

Cow’s milk allergy (CMA) is the most common allergic disease in infancy. It is not clear, whether infants with CMA have an increased risk of developing other allergic diseases later in life, the so-called “allergic march”. We aimed to detect genetic associations of CMA using reported single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) in other allergic diseases and genetic mutations within the filaggrin (FLG) gene. Both to investigate possible causes of CMA, which also suggests an “allergic march”.

Methods

Thirty children from the Dutch EuroPrevall birth cohort study with CMA in infancy and twenty-three healthy controls were studied. Six candidate SNPs were selected (minor allele frequency 10–50 % combined with a large effect) based on the literature. Thirteen FLG candidate mutations were selected spread over repeats 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9 and 10 respectively.

Results

We found two SNP’s, rs17616434 (P = 0.002) and rs2069772 (P = 0.038), significantly associated with CMA. One is located near the toll like receptor 6 (TLR6) gene, which functionally interacts with toll-like receptor 2, and is associated with an increased risk of other allergic diseases. One is located at the Interleukin 2 (IL2) locus. Twelve FLG amplicons were analyzed, but showed no significant enrichment. Nevertheless, we did observe more FLG mutations in the CMA-group compared to controls.

Conclusion

We significantly associated two SNPs with CMA, suggesting that variation in the TLR6 and IL2 genes contribute to the expression of CMA. In addition, since TLR6 and IL2 were earlier associated with other later onset allergies, this also favours the “allergic march” hypothesis. We observed more FLG mutations in the CMA-group, albeit we found no statistical significant enrichment of FLG mutations. Further studies are necessary to investigate the role of common variants and FLG or other skin barrier gene mutations in CMA.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Cow’s milk allergy

Cow’s milk allergy (CMA) is the most common food allergy in young children, although an accurate incidence is difficult to establish because of discrepancies between self-reported and proper diagnosed allergy [1–4]. CMA and other food allergies have a heterogeneous clinical presentation, the estimated heritability of food-specific IgE ranged from 0.15 (cow’s milk) to 0.35 (wheat) [5, 6]. Young children are likely to develop tolerance for cow’s milk protein within a few years. However, infants who suffered from CMA in their early childhood seem to have an increased risk to develop other allergic diseases like asthma later in life [6–12]. Accumulating evidence suggest involvement of gut-microbiota, maturation of the immune-system and epicutaneous allergen sensitization [6, 13, 14]. Pre- and postnatal environmental factors, parent-of-origin factor and stress are likely to be involved in the susceptibility and expression of allergy [15]. So far, a clear cause for CMA has not been found.

Genetic component of food allergy

Genetic surveys on food allergy (FA) are to our knowledge still limited to candidate gene studies, and studies investigating CMA solely are not available. GWAS on other atopic diseases like asthma and eczema identified few candidate genes, as presented by Bonnelykke et al. However, these genes were only found in single FA allergy studies, as presented by Tan et al. [16–18]. Recently, it was shown that loss-of-function mutations of filaggrin (FLG) are a major risk factor for peanut food allergy [19]. FLG has already been described in studies on eczema [16, 20]. The FLG protein is an important skin barrier protein, but is not expressed in the gastrointestinal tract [13, 19]. Studies on the sensitizing mechanisms involved in FA, suggest that exposure to food antigens through the skin, i.e. epicutaneous, leads to allergic sensitization while (early) oral administration of food antigens just may prevent the onset of allergy [13]. An impaired skin barrier is however not essential for epicutaneous sensitization. It has been shown that high molecular weight antigens can be taken up by dendritic cells, which are present in hair follicles, which on turn can either initiate a sensitization or repression of immunological responses [13, 21]. During a sensitization period, different immunological processes may lead to the full expression of allergy.

To summarize, susceptibility factors among different types of allergies other than CMA are well investigated. It is known that CMA is an ultimate complex disease involving different immunological pathways and different environmental factors. Here we aim to discover new insight in the genetic susceptibility of CMA by means of: (1) Genetic association of six allergy associated common and high effect genetic variants identified by GWAS and (2) genetic association of rare but high effect genetic mutations in the filaggrin gene.

Methods

Dutch EuroPrevall Birth Cohort Study

In this study only children participating in the Dutch EuroPrevall Birth Cohort Study were investigated. The EuroPrevall study has been described in detail previously [3, 4, 22, 23]. In summary, children were included around birth and standardized measurements were performed by questionnaires. All children with symptoms suggestive of CMA underwent, among others a double blind placebo controlled food challenge (DBPCFC). Age-matched healthy control children were selected from the entire Dutch cohort. In both symptomatic and control children measurements where repeated annually. Controls had no symptoms suggestive of any food allergy nor suffered from atopic dermatitis. In all children undergoing blood drawing an attempt was made to obtain one full blood sample (EDTA KE 2.6 ml Monovette, Sarstedt BV, Etten-Leur, Netherlands) for DNA-isolation too. The Medical Ethics Committee of the Academic Medical Hospital (METC 06/005) approved the Dutch EuroPrevall Birth Cohort Study. Written informed consent, for both the study and genetic sampling, was obtained from both parents of each child, unless only one of them had parental rights.

CMA diagnosis

DBPCFC is the gold standard for diagnosing CMA and the challenge of choice according to the study protocol [22–24]. All children suspected of CMA were challenged according the international gold standard. The DBPCFC procedure was described in detail previously [3]. DBPCFC was repeated annually, in children with CMA, until the child was tolerant for CMP [3, 22]. Tolerance was defined as previously a positive DBPCFC for CMA, but at DNA-sampling a negative DBPCFC and/or eating CMP without experiencing symptoms.

Samples selected for genetic analysis

DNA samples of 20 children with proven CMA were selected, based on the longest possible time between the age of DNA-sampling and the age of CMP-tolerance. Since DNA is generally assumed to be stable throughout life we state that former CMA patients and active CMA patients represent both CMA cases. Also ten samples of children with proven CMA who developed CMP tolerance during the course of the study were selected, called former CMA children. Together these 30 samples are called the CMA-group. Control samples (N = 23), were selected from the group of control children and matched on age at DNA-sampling.

Patient characteristics were analysed with t test (Mann–Whitney U test when data was not normally distributed) for continuous parameters. Chi square test was used for categorical variables and Chi square test for trend for multiple categories categorical variables. All characteristics were analysed using SPSS version 20 (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Armonk, NY).

Genetic association analysis

GWAS-studies reporting on SNPs associated with sensitization and/or allergy were selected [25]. SNP Inclusion criteria were based on the minor allele frequency (MAF) of 20–50 % and an odds ratio (OR) >1.2 [26, 27]. Based on the literature and our prior stated selection criteria, six SNPs were selected for evaluation. A description of the SNPs with regard nearby located genes is described in Table 1. Linkage disequilibrium (LD) was used to identify the most plausible involved gene, using LD plots per SNP on SNAP Broad institute with the following values: R2 = 0.8, distance limit = 500, CEU population [28]. Target reference sequences were downloaded using the database ENSEMBL [29]. These reference sequences were subsequently submitted to the web tool Primer3 in order to obtain a primer set. Primers were M13 tail extended [30]. Primer sequences of all 6 SNPs are described in Additional file 1: Table S1. Final quality control of the primer set was performed using the web tool SNPCheck [31].

The FLG gene involves at least ten highly homolog repeat sequences. The primer sequences or primer design for detection of FLG mutations was based on the report of Sandilands et al. [32]. In total we selected 13 FLG candidate mutations spread over repeats 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9 and 10 respectively (Table 2) [32]. Mutations reported only in the Chinese or Japanese population (3321delA and S2554X) were not included in this study. Since for most FLG primers specificity is based on not more than three repeat specific bases, the highest possible annealing temperature was used in the PCR in order to obtain the required regional specificity. All mutations were analysed using PCR, followed by Sanger sequencing. FLG Primers sequences are described in Additional file 1: Table S2. SNPs and FLG mutations were Sanger sequenced using standard protocols (BigDye Terminator® mix, Applied Biosystems) and analysed using an ABI3730® of Applied Biosystems.

Raw sequence data was analysed using CodonCode Aligner® and Alamut® software. Since all tested mutations in the FLG gene result in an absent or defective protein, we constructed a cumulative variant score per patient. This cumulative score included a score of zero risk alleles versus one or more risk alleles present in exon 3 repeats of FLG. The CMA-group was compared to controls. In population based genetic studies the Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) is a golden standard for quality control of the analysed genotypes. Deviation of this equilibrium indicates genotyping errors or the presence of a certain genetic selection bias. Since we did analyze in this study a strongly selected sample of CMA patients, which obviously does not represent the general population, it would be inappropriate to apply the Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium as genotyping quality control in this study. All genetic statistical analyses were performed in SPSS (v20) using a Pearson’s Chi square test or Fisher’s exact test. P values <0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Patient and control characteristics are shown in Table 3. Controls and children with CMA were well matched except for age at DNA-sampling. Children with CMA were significantly younger (P = 0.008) compared to controls. Our CMA group consists of both IgE as well as non-IgE mediated CMA, with slightly more IgE positive children (specific IgE >0.35 kU/L, P = 0.044) in the CMA group compared to controls. Comparison of the former CMA group, showed no significant difference in age at DNA-sampling (P = 0.71) nor IgE status (P = 0.49).

Genetic contribution of common variants to CMA

For two SNPs we observed significant enrichment of risk genotypes in the CMA-group compared to controls, illustrated in Table 4. For rs17616434, located on chromosome 4; TLR10/1/6 and FAM114A1 locus, C/C risk alleles were absent in the control group while 9 CMA/former CMA subjects showed this genotype (P = 0.002). The rs17616434 C/T and T/T genotypes were both enriched in the controls. For rs2069772 located on chromosome 4 as well, the T/T genotype was enriched in the CMA-group compared to the controls (80 vs. 46.7 % respectively), while the heterozygotes (C/T) and common genotype (C/C) was enriched in the controls (P = 0.038). Analysis based on the genotype frequencies within the CMA-group vs. controls was insignificant associated (P > 0.05) for rs2155219 (LRRC32 locus), rs6586513 (CROCC/ATP13A2/SDHB/MFAP2 locus), rs3860069 (TLR6/10/1 and FAM114A1 locus) and rs6898653 (SEMA6A locus).

Genetic contribution of rare FLG mutations to CMA

The investigated FLG-mutations were covered by 9 amplicons of which we successfully optimized PCR conditions for 8 amplicons. The 4th amplicon, covering the R1474X mutation in FLG repeat 4, did not show consistent results and was therefore excluded from analysis (data not shown). The latter mutation is extremely rare and was only reported in the Irish population [32].

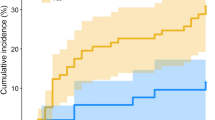

Figure 1 illustrates the percentage of present risk alleles per group. According to the report of Sandilands et al. [32] some mutations were, so far, only observed in European and/or Dutch populations annotated as dashed bars in this figure. One sample, homozygote for the 2282del4 mutation involved a CMA patient. Geographic origin/ethnicity are known confounders in genetic surveys. Therefore, we evaluated the ethnic distribution (Fig. 2) and observed no difference between the two groups. All FLG mutations are rare, and in combination with a relative small sample, this implies extremely low statistical power. In order to diminish this power problem we counted per sample the number of present mutations yielding a cumulative FLG risk allele score. Samples who carried 1 or more risk alleles were annotated as 1. Figure 3 illustrates the scores in the CMA-group and controls. Although insignificant (Chi square test), more risk alleles carriers were present in the CMA-group compared to controls.

Enrichment analysis of filaggrin risk alleles in cow’s milk allergy patients vs. controls. Percent present risk alleles: total number of alleles/number of risk alleles per group [cow’s milk allergy (CMA) patients, former CMA patients and controls]. Dutch/EUR pop column indicates for every FLG mutation the discovery population according Sandilands et al. only and does not represent an actual percentage

Discussion

In this study we observed association of two earlier reported non-CMA allergies and/or allergy sensitization associated SNPs with CMA. Although insignificant, we observed more FLG mutations in the CMA-group compared to controls which suggest that a role of the FLG-gene in CMA cannot be excluded. Since our candidates were earlier reported to be associated with other types of late(r) onset allergic diseases, our data suggest not only that rs17616434, rs2069772 and FLG mutations are involved in CMA, but also suggest that these genetic variations might contribute to the so-called “allergic march”.

Genetic analysis

We analysed six SNPs which have been described previously in relation to allergic diseases [26, 27]. Out of these six, two SNPs showed significantly different genotypic distribution between CMA and controls. First, rs17616434 (P = 0.002) was associated with CMA and is located near a cluster of toll like receptor (TLR1, 6, 10) genes, which has earlier been associated with allergic disease [33]. Secondly, rs2069772 (P = 0.038), was earlier described to be associated with allergic rhinitis, and is located near the IL2 and KIAA1109 genes [27]. IL2 is known to be involved in cytokine secretion that stimulates proliferation of B and T -cells. The other gene, KIAA1109, is known to be involved in celiac disease, a disease characterized by a strong immunological response to food proteins (gluten), found in wheat, rye and barley [34]. Moreover, the KIAA1109/Tenr/IL2/IL21 locus was also earlier associated with another immunological disorder, namely rheumatoid arthritis [35]. Therefore, both IL2 and KIAA1109 are good candidates to be involved in CMA. Earlier reports involving allergic diseases have shown that a defective FLG-gene was involved, albeit the prevalence of these mutations is ethnicity specific [32]. In our cohort we constructed a cumulative score of FLG-mutations. Although, the absolute number of mutations was higher in the CMA-group this difference was not statistical significant. The presence of ethnic specific mutations in our sample of mainly Dutch children was in concordance with the report of Sandilands et al., with exception of S3247X mutation, which was reported only in the Irish population [32]. Since FLG mutations are rare and our study sample is small we cannot state that FLG is not involved in CMA. To our knowledge, FLG has not been studied in CMA before. Therefore, studies involving a larger sample size are necessary to conclusively rule out or rule in the involvement of FLG in CMA.

Allergic march

The allergic march hypothesize that children who suffered from food allergy or atopic dermatitis in early childhood have an increased risk of developing other allergic diseases, e.g. asthma and allergic rhinitis, in later in life. However, evidence for the existence of the allergic march is still very limited [6–12]. Recent reports describe pathways involved in allergic diseases and implied common genetic variation behind these affected pathways, among others, defects involving the skin barrier. The filaggrin protein is involved in maintaining a healthy skin barrier [18, 36]. Although in our study rare FLG mutations were not significantly enriched in CMA patients, we did observe more FLG mutations in our CMA group. The function of regulatory T-cells and the Th2 responses have been previously reported in relation to allergic diseases as well. These pathways have been associated with several other allergic diseases, which might favour the allergic march hypothesis, since the onset of these different types of allergies seem to manifest at specific ages [18, 36]. In our small sample study, we found a significant associated locus located close to the IL2 gene which is involved in the Th2 response. Both our observations on FLG mutations and the IL2 locus favour the allergic march hypothesis but have to be confirmed in a prospective study design.

Strength and weaknesses of the study

The main strength of the studied samples is that CMA is diagnosed according to the current available, internationally recommended, gold standard [24]. Furthermore, clinical data are well documented due to the setup of the study with regular questionnaires [22]. Unfortunately, it was not possible to obtain DNA-samples in all children. Furthermore, the amount of blood drawing for research purposes in infants is in the Netherlands limited to 2.5 ml. These are both limiting the sample size of this study. This resulted in missing values for statistical analysis, however there were no significant differences in distribution between valid and missing cases between CMA-infants and controls (data not shown). Since this is only a very small sample size study in a very heterogeneous disease, further studies in larger cohorts are necessary. Obviously, many more genetic and environmental factors are involved in the development of CMA. With respect to an epidemiological approach unravelling mechanisms involved in CMA, large cohorts are essential. On the other hand, using well characterized small cohorts or even single cases might be essential to elucidate distinct mechanisms, that underlie at the basis of the complex character of CMA.

Conclusion

Current studies indicates that genetic variation of TLR6 and IL2, which were earlier reported to be associated with non-CMA allergies and/or allergy sensitization, contribute to the expression of CMA in young children. In addition, this favours the “allergic march” hypothesis. Furthermore, we cannot exclude a possible role for FLG-mutations being involved in CMA or the sensitization process prior to the establishment of CMA. Follow-up studies are necessary before definite conclusions about a link between early onset CMA and expression of later onset other allergic diseases can be drawn.

Abbreviations

- CMA:

-

cow’s milk allergy

- CMP:

-

cow’s milk protein

- DBPCFC:

-

double blind placebo controlled food challenge

- DNA:

-

deoxyribonucleic acid

- FA:

-

food allergy

- FLG :

-

filaggrin

- GWAS:

-

genome wide association studies

- HWE:

-

Hardy–Weinberg Equilibrium

- LD:

-

linkage disequilibrium

- MAF:

-

minor allele frequency

- OR:

-

odds ratio

- SNP:

-

single nucleotide polymorphism

References

Chafen JJ, Newberry SJ, Riedl MA, Bravata DM, Maglione M, Suttorp MJ, et al. Diagnosing and managing common food allergies: a systematic review. JAMA. 2010;303(18):1848.

Rona RJ, Keil T, Summers C, Gislason D, Zuidmeer L, Sodergren E, et al. The prevalence of food allergy: a meta-analysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120(3):638.

Petrus NC, Schoemaker AF, van Hoek MW, Jansen L, Jansen-van der Weide MC, van Aalderen WM, Sprikkelman AB. Remaining symptoms in half the children treated for milk allergy. Eur J Pediatr. 2015;174(6):759.

Schoemaker AA, Sprikkelman AB, Grimshaw KE, Roberts G, Grabenhenrich L, Rosenfeld L, et al. Incidence and natural history of challenge-proven cow’s milk allergy in European children—EuroPrevall birth cohort. Allergy. 2015;70:963.

Tsai HJ, Kumar R, Pongracic J, Liu X, Story R, Yu Y, et al. Familial aggregation of food allergy and sensitization to food allergens: a family-based study. Clin Exp Allergy. 2009;39(1):101.

Benhamou AH, Schappi Tempia MG, Belli DC, Eigenmann PA. An overview of cow’s milk allergy in children. Swiss Med Wkly. 2009;139(21–22):300.

Host A, Halken S. A prospective study of cow milk allergy in Danish infants during the first 3 years of life. Clinical course in relation to clinical and immunological type of hypersensitivity reaction. Allergy. 1990;45(8):587.

Host A, Halken S, Jacobsen HP, Christensen AE, Herskind AM, Plesner K. Clinical course of cow’s milk protein allergy/intolerance and atopic diseases in childhood. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2002;13(Suppl):15.

Longo G, Berti I, Burks AW, Krauss B, Barbi E. IgE-mediated food allergy in children. Lancet. 2013;382:1656.

Morita H, Nomura I, Matsuda A, Saito H, Matsumoto K. Gastrointestinal food allergy in infants. Allergol Int. 2013;62(3):297.

Saarinen KM, Pelkonen AS, Makela MJ, Savilahti E. Clinical course and prognosis of cow’s milk allergy are dependent on milk-specific IgE status. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;116(4):869.

Alduraywish SA, Lodge CJ, Campbell B, Allen KJ, Erbas B, Lowe AJ, Dharmage SC. The march from early life food sensitisation to allergic disease: a systematic review and meta-analyses of birth cohort studies. Allergy. 2015;71:77.

Matsumoto K, Saito H. Epicutaneous immunity and onset of allergic diseases—per-”eczema”tous sensitization drives the allergy march. Allergol Int. 2013;62(3):291.

Noverr MC, Huffnagle GB. The ‘microflora hypothesis’ of allergic diseases. Clin Exp Allergy. 2005;35(12):1511.

Chen W, Mempel M, Schober W, Behrendt H, Ring J. Gender difference, sex hormones, and immediate type hypersensitivity reactions. Allergy. 2008;63(11):1418.

Tan TH, Ellis JA, Saffery R, Allen KJ. The role of genetics and environment in the rise of childhood food allergy. Clin Exp Allergy. 2012;42(1):20.

Lockett GA, Holloway JW. Genome-wide association studies in asthma; perhaps, the end of the beginning. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;13(5):463.

Bonnelykke K, Sparks R, Waage J, Milner JD. Genetics of allergy and allergic sensitization: common variants, rare mutations. Curr Opin Immunol. 2015;36:115.

Asai Y, Greenwood C, Hull PR, Alizadehfar R, Ben-Shoshan M, Brown SJ, et al. Filaggrin gene mutation associations with peanut allergy persist despite variations in peanut allergy diagnostic criteria or asthma status. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132(1):239.

van den Oord RA, Sheikh A. Filaggrin gene defects and risk of developing allergic sensitisation and allergic disorders: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2009;339:b2433.

Dioszeghy V, Mondoulet L, Dhelft V, Ligouis M, Puteaux E, Benhamou PH, Dupont C. Epicutaneous immunotherapy results in rapid allergen uptake by dendritic cells through intact skin and downregulates the allergen-specific response in sensitized mice. J Immunol. 2011;186(10):5629.

Keil T, McBride D, Grimshaw K, Niggemann B, Xepapadaki P, Zannikos K, et al. The multinational birth cohort of EuroPrevall: background, aims and methods. Allergy. 2010;65(4):482.

McBride D, Keil T, Grabenhenrich L, Dubakiene R, Drasutiene G, Fiocchi A, et al. The EuroPrevall birth cohort study on food allergy: baseline characteristics of 12,000 newborns and their families from nine European countries. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2012;23(3):230.

Boyce JA, Assa’ad A, Burks AW, Jones SM, Sampson HA, Wood RA, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of food allergy in the United States: summary of the NIAID-sponsored expert panel report. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126(6):1105.

National Human Genome Research Institute. http://www.genome.gov/gwastudies. Catalog Data Update: 20 Feb 2015.

Bonnelykke K, Matheson MC, Pers TH, Granell R, Strachan DP, Alves AC, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies identifies ten loci influencing allergic sensitization. Nat Genet. 2013;45(8):902.

Ramasamy A, Curjuric I, Coin LJ, Kumar A, McArdle WL, Imboden M, et al. A genome-wide meta-analysis of genetic variants associated with allergic rhinitis and grass sensitization and their interaction with birth order. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128(5):996.

SNP Annotation and Proxy Search Broad Institute. Version 2.2. http://www.broadinstitute.org/mpg/snap.

Ensembl. http://www.ensembl.org/index.html. Accessed Dec 2014.

Koressaar T, Remm M. Enhancements and modifications of primer design program Primer3. Bioinformatics. 2007;23(10):1289.

National Genetics Refence Laboratory. SNPCheck version 3.1.1, 2013. http://www.ngrl.org.uk/Manchester/projects/informatics/snpcheck.

Sandilands A, Terron-Kwiatkowski A, Hull PR, O’Regan GM, Clayton TH, Watson RM, et al. Comprehensive analysis of the gene encoding filaggrin uncovers prevalent and rare mutations in ichthyosis vulgaris and atopic eczema. Nat Genet. 2007;39(5):650.

Reijmerink NE, Kerkhof M, Bottema RW, Gerritsen J, Stelma FF, Thijs C, et al. Toll-like receptors and microbial exposure: gene-gene and gene-environment interaction in the development of atopy. Eur Respir J. 2011;38(4):833.

van Heel DA, Franke L, Hunt KA, Gwilliam R, Zhernakova A, Inouye M, et al. A genome-wide association study for celiac disease identifies risk variants in the region harboring IL2 and IL21. Nat Genet. 2007;39(7):827.

Teixeira VH, Pierlot C, Migliorini P, Balsa A, Westhovens R, Barrera P, et al. Testing for the association of the KIAA1109/Tenr/IL2/IL21 gene region with rheumatoid arthritis in a European family-based study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11(2):R45.

Pellerin L, Jenks JA, Begin P, Bacchetta R, Nadeau KC. Regulatory T cells and their roles in immune dysregulation and allergy. Immunol Res. 2014;58(2–3):358.

Authors’ contributions

PH supervised laboratory experiments, analysed data and drafted the manuscript. NP collected clinical data, analysed data and drafted the manuscript. AV, FS and KL performed laboratory experiments and critically revised the manuscript. RH interpreted the data and critically revised the manuscript. MM and AS supervised the studies (MM laboratory; AS clinical studies) and critically revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all children and their parents for participating in the Dutch EuroPrevall Birth Cohort Study. Furthermore the authors would like to thank everyone involved in collecting clinical data. The employees of the department Department of Parasitology, Leiden University Medical Center, for storing blood samples.

Competing interests

This study was supported by an unrestricted grant from the “Stichting Steun Emma”, Emma Children’s Hospital, Academic Medical Center, The Netherlands. The EuroPrevall study is funded by the European Commission (FOOD-CT_2005-514000). The Dutch cohort received unrestricted grants from Nutricia, the Netherlands, Nutricia Advanced Medical Nutrition, the Netherlands, AstraZeneca, the Netherlands, TEVA, the Netherlands and GlaxoSmithKline, the Netherlands.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Peter Henneman and Nicole C.M. Petrus contributed equally to this work

Marcel Mannens and Aline B. Sprikkelman contributed equally to this work

Additional file

13601_2016_96_MOESM1_ESM.doc

Additional file 1. Primer sequences. a Primer sequences candidate SNPs, b Primer sequences candidate Filaggrin (FLG) mutations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Henneman, P., Petrus, N.C.M., Venema, A. et al. Genetic susceptibility for cow’s milk allergy in Dutch children: the start of the allergic march?. Clin Transl Allergy 6, 7 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13601-016-0096-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13601-016-0096-9