Abstract

Background

Given that metformin is the most common pharmacological therapy for type 2 diabetes, understanding the function of this drug is of great importance. Hepatic metformin transporters are responsible for the pharmacologic action of metformin. However, epigenetics in genes encoding metformin transporters has not been fully elucidated. We examined the DNA methylation of these genes in the liver of subjects with type 2 diabetes and tested whether epigenetic alterations associate with diabetes medication, i.e., metformin or insulin plus metformin treatment.

Results

DNA methylation in OCT1 encoded by SLC22A1, OCT3 encoded by SLC22A3, and MATE1 encoded by SLC47A1 was assessed in the human liver. Lower average and promoter DNA methylation of SLC22A1, SLC22A3, and SLC47A1 was found in diabetic subjects receiving just metformin, compared to those who took insulin plus metformin or no diabetes medication. Moreover, diabetic subjects receiving just metformin had a similar DNA methylation pattern in these genes compared to non-diabetic subjects. Notably, DNA methylation was also associated with gene expression, glucose levels, and body mass index, i.e., higher SLC22A3 methylation was related to lower SLC22A3 expression and to insulin plus metformin treatment, higher fasting glucose levels and higher body mass index. Importantly, metformin treatment did also directly decrease DNA methylation of SLC22A1 in hepatocytes cultured in vitro.

Conclusions

Our study supports that metformin decreases DNA methylation of metformin transporter genes in the human liver. Moreover, higher methylation levels in these genes associate with hyperglycaemia and obesity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Metformin is the most common pharmacological therapy for type 2 diabetes (T2D). As metformin’s primary action is considered to be in the liver, hepatic uptake by organic cation transporters (OCT1 encoded by SLC22A1 and OCT3 encoded by SLC22A3) and secretion to the bile through an efflux transporter (MATE1 encoded by SLC47A1) are essential for the pharmacological effect of this drug [1]. Mouse models have provided valuable insights showing the important role of metformin transporters in the liver for the pharmacological effect of metformin [2,3,4,5,6]. Human studies have focused on genetic variants in these transporters to elucidate their role in metformin response [7,8,9,10,11]. They showed that genetic variants associate with OCT1 protein and mRNA expression and OCT3 mRNA expression in the human liver [12].

Although genetics of metformin transporters have been described, epigenetic regulation of these genes is less studied. There are only two studies related to cancer assessing DNA methylation of SLC22A1 and SLC22A3 in the human liver [13, 14]. Here, higher DNA methylation of SLC22A1 was associated with decreased expression of this gene in hepatocellular carcinoma.

Given that hepatic entry of metformin is necessary for its glucose-lowering effects in patients with T2D, it would be relevant to investigate epigenetic regulation of the genes encoding metformin transporters in the human liver. Therefore, our aim was to investigate whether DNA methylation and gene expression of SLC22A1, SLC22A3, and SLC47A1 are associated with diabetes medication in the human liver. Here, we compared diabetic patients taking metformin versus those taking insulin plus metformin or no diabetes medication as well as non-diabetic subjects. We also tested if DNA methylation in these transporters was associated with gene expression, fasting glucose levels or body mass index (BMI).

Results

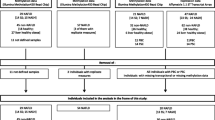

Clinical characteristics of the non-diabetic and T2D participants according to medication are shown in Additional file 1: Table S1. Diabetic subjects who were administered just metformin (n = 20) had lower insulin, glucose, and HOMA-IR levels compared to subjects who received insulin plus metformin (n = 10) or no diabetes medication (n = 3). Moreover, diabetic subjects who took just metformin had similar insulin and HOMA-IR levels compared to non-diabetic subjects.

We next examined if DNA methylation in the SLC22A1, SLC22A3, and SLC47A1 genes was different in the human liver according to diabetes medication. Patients who took metformin had lower average degree of DNA methylation, especially in the promoter region, in all studied transporter genes compared to subjects who received insulin + metformin and subjects who did not receive any diabetes medication (Fig. 1a–c). Of note, in the metformin (n = 20) and in the insulin + metformin (n = 10) groups, six and two subjects respectively were also on other oral diabetes medication (Sitagliptin or Glimepiride) (Additional file 1: Table S1). However, these medications did not seem to affect methylation of SLC22A1, SLC22A3, and SLC47A1 (Additional file 1: Table S2), and we therefore included those subjects in our analyses. Furthermore, DNA methylation in six CpG sites annotated to SLC22A1, one CpG site annotated to SLC22A3 and six CpG sites annotated to SLC47A1 were significantly different with false discovery rate (FDR) less than 5% according to diabetes medication. Notably, DNA methylation in these individual CpG sites was similar or even lower in diabetic subjects who received metformin compared to non-diabetic individuals (Table 1).

DNA methylation of metformin transporter genes in human liver of patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D) and non-diabetic subjects. a–c Average and promoter DNA methylation according to diabetes medication (20 T2D patients receiving metformin, 10 T2D patients on insulin + metformin therapy, and 3 T2D patients on no medication) and non-diabetic subjects. P values from the ANCOVA are shown after adjusting for age, sex, and the presence of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). Post-hoc analyses were used to compare groups: a P < 0.05 compared to non-diabetic subjects, b P < 0.05 compared to metformin treatment. Adjusted means and standard errors are shown

We next tested whether metformin and/or insulin treatment might affect DNA methylation in metformin transporter genes directly in cell cultures. Here, methylation of three CpG sites (cg24864413, cg11696576, cg01530032) was analyzed by pyrosequencing. These sites were selected as they were the most significant sites for each of the three studied genes (Table 1) and had relatively large differences in methylation by diabetes medication in the human liver. In agreement with the liver data (Fig. 2a), cg24864413 annotated to SLC22A1 had lower methylation in cells treated with metformin compared to insulin + metformin (P = 0.016) and to untreated cells (P = 0.025) (Fig. 2b). Moreover, insulin treatment alone also increased methylation in this CpG site in the cells (P = 0.035). No differences in DNA methylation were observed for the other two CpG sites (Additional file 1: Figure S1).

DNA methylation in the promoter region of SLC22A1 (cg24864413). a DNA methylation of SLC22A1 in human liver was lower in type 2 diabetes subjects receiving just metformin (n = 20), compared to those who took insulin plus metformin (n = 10) or no diabetes medication (n = 3). P value from the ANCOVA is shown after adjusting for age, sex, and the presence of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). Post-hoc analyses were used to compare groups: ***P < 0.0001. Adjusted means and standard errors are shown. b DNA methylation of SLC22A1 in hepatocytes cultured in vitro was lower after 8 h of metformin treatment (0.5 mM) compared to insulin plus metformin treatment and to control Huh-7 cells, whereas insulin treatment (100 nM) increased DNA methylation of this CpG site (n = 4). *P < 0.05, a P < 0.05 compared to control, all analyzed by a paired t test. Means and standard deviations are shown

We further related DNA methylation to gene expression of the studied metformin transporters in the human liver of 42 subjects. Pearson correlations showed that liver DNA methylation in some individual CpG sites (one CpG at the SLC22A1 locus, three CpGs at the SLC22A3 locus, and one CpG at the SLC47A1 locus) was associated with expression of its corresponding gene (P < 0.05) (Table 2). These associations remained after adjusting for age, sex, and the presence of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). However, while SLC22A1 and SLC47A1 had higher expression than SLC22A3, no expression differences were observed for any of the three metformin transporters according to diabetes medication (Additional file 1: Figure S2).

We also studied whether liver DNA methylation in the metformin transporter genes was related to glucose levels or BMI in the 95 subjects from the Kuopio Obesity Surgery Study (Table 3). Glucose levels and BMI were positively correlated with the degree of average methylation of SLC22A1 and SLC47A1 and methylation in the promoter region of SLC22A1, SLC22A3, and SLC47A1. Higher DNA methylation of cg24864413 (SLC22A1), cg06295784 (SLC22A3), cg07883823 (SLC22A3), cg01530032 (SLC47A1), cg07829432 (SLC47A1) and cg12550399 (SLC47A1) was associated with higher glucose levels (q value < 0.05). Moreover, DNA methylation in cg13466809 (SLC22A1), cg06295784 (SLC22A3), and cg25313204 (SLC22A3) showed positive correlations with BMI (q value < 0.001).

A Venn diagram was finally made to show the associations between DNA methylation of metformin transporters and diabetes medication, glucose levels and BMI (Fig. 3). An overlap including DNA methylation in five CpG sites was found for the three factors, i.e., cg13466809 (SLC22A1), cg06295784 (SLC22A3), cg25313204 (SLC22A3), cg01530032 (SLC47A1), and cg12550399 (SLC47A1) displayed lower DNA methylation levels in the metformin group and were positively associated with glucose and BMI.

Venn diagram showing associations between DNA methylation of the three metformin transporters genes and diabetes medication, glucose levels, and body mass index (BMI). Overall, DNA methylation of 29 CpG sites was associated with either diabetes medication, glucose levels or BMI with a P value < 0.05. An overlap with differential DNA methylation in five CpG sites was observed for the three factors

Discussion

In this study, we describe DNA methylation and gene expression of SLC22A1, SLC22A3, and SLC47A1, which respectively encode the three metformin transporters OCT1, OCT3, and MATE1, in the human liver. In agreement with a previous study where OCT1 was found to be the most expressed drug transporter in the liver [15], we found higher mRNA expression of SLC22A1 than SLC22A3 (Additional file 1: Figure S2A). SLC47A1 was also highly expressed in the liver, as previously reported [16].

Metformin transporter genes have been studied in vivo in rodents to explain metformin pharmacodynamics. The distribution of metformin to the liver in Oct1 −/− mice was reduced 30-fold compared with wild-type mice [6], and the glucose-lowering effects of metformin were totally abolished in the knock out mice [3]. Liver accumulation of metformin was also reduced in Oct3 −/− mice [2]. These results support that OCT1/SLC22A1 and OCT3/SLC22A3 are responsible for hepatic uptake of metformin. In contrast, the lack of SLC47A1 expression led to 69-fold higher metformin concentrations in the liver [4, 5], confirming the role that MATE1/SLC47A1 plays in hepatic excretion of metformin. Indeed, liver expression of these metformin transporter genes is crucial for the antidiabetic effect of metformin.

Recent studies from our group and others have shown that epigenetics play an important role in the pathogenesis of T2D in different tissues, including the human liver [17,18,19,20,21]. But, it is uncertain whether epigenetics is associated with diabetes medication, such as metformin or insulin. This is the first study reporting differential DNA methylation in metformin transporter genes in the human liver according to diabetes medication. Subjects who just received metformin presented lower methylation levels, mainly in the promoter region, in all three transporter genes compared to those participants who were taking insulin plus metformin or no diabetes medication. To dissect if diabetes medication has a direct impact on methylation, we exposed liver cells to metformin and insulin in vitro. Interestingly, methylation of SLC22A1 was lower in cells exposed to metformin and higher after insulin treatment, which is in line with the data seen in the human liver. The fact that methylation of some studied CpG sites was not affected by the exposure in vitro does not exclude that longer metformin or insulin treatments could have effects. T2D patients are given a long-term therapy, whereas the cells were treated for 8 h mimicking an acute therapy. Overall, our in vivo and in vitro data support that metformin therapy is associated with lower DNA methylation of metformin transporter genes in the liver suggesting that epigenetics could be a potential mechanism for metformin action in the human liver. Accordingly, a recent study has shown that metformin alters DNA methylation in endometrial cancer cells [22]. The demethylation process in metformin transporters induced by metformin could have occurred passively or actively by ten-eleven translocation (TET) enzymes [23], since these enzymes play an important role in the development and function of the human liver [24]. Moreover, AMPK pathway, activated by metformin, elevates α-ketoglutarate metabolite which is required by TET catalytic reaction for the DNA demethylation process [25]. Nevertheless, more studies are needed to dissect this mechanism. In addition, diabetics who were only on metformin therapy had a similar or lower degree of methylation in these metformin transporter genes compared to non-diabetic people, suggesting a possible normalization of the DNA methylation status in these people. However, it is also possible that insulin increases methylation in metformin transporter genes since both the control and the insulin + metformin groups presented higher serum insulin levels. Additionally, insulin treatment increased methylation in vitro. It should be noted that we used a lower metformin concentration (0.5 mM) than other in vitro studies (5–10 mM) [26] to be closer to the physiological level seen in humans (~ 50 uM in plasma from T2D subjects) [26].

Moreover, we observed that higher DNA methylation in these transporters was associated with higher glucose levels and BMI. Higher methylation and lower expression of SLC22A1 and SLC22A3 was previously observed in hepatocellular carcinoma and prostate tumor compared with matched normal samples [13, 14] supporting that higher methylation in metformin transporter genes could be associated with disease. However, there are no further studies assessing DNA methylation in metformin transporters to compare with our results.

The clinical response to metformin shows considerable inter-individual variation. Human studies found genetic variants in SLC22A1, SLC22A3, and SLC47A1 that are associated with an impaired metformin transport and a poor glycaemic response to metformin [7,8,9,10,11]. One study also showed that genetic variants influence OCT1 and OCT3 expression and function in the human liver [12]. Epigenetic factors may also regulate gene expression [27]. We observed that methylation of some sites near to these genes correlated with expression, supporting that methylation in metformin transporter genes is related with expression in the human liver. For example, higher methylation in a CpG site located in SLC22A3 was associated with lower expression in the human liver and also with insulin plus metformin therapy, higher glucose levels, and BMI. Higher DNA methylation of SLC22A3 could be a potential mechanism to decrease expression of this gene, leading to reduced antidiabetic effects of metformin resulting in hyperglycaemia. DNA methylation was initially thought to be a silencing mark. However, merging data show that the role of DNA methylation is much more complex than initially thought, and it is dependent on genomic location and can be dependent on several other factors [27]. DNA methylation in the gene body has been associated with increased gene expression potentially by increased elongation, while methylation in the promoter region often associate with decreased transcriptional activity [28]. DNA methylation may also regulate expression of non-coding RNAs, alternative splicing events, and the overall genomic stability [27]. Recent studies also point out that CpG sites are positively or negatively associated to gene expression depending on other epigenetic marks such as histone marks and chromatin accessibility [29]. These are likely reasons for why we found positive and negative correlations between DNA methylation of individual CpG sites in metformin transporters and gene expression.

The low number of patients with no diabetes medication could be a limitation in this study. However, the fact that statistical differences were found suggests that potential type II errors were overcome. Another limitation of this study is the lack of genetics data that may provide evidence for interactions between genetic and epigenetic events of metformin transporter genes in the liver. Nevertheless, our main aim was to assess DNA methylation of metformin transporter genes which has been scarcely studied.

Conclusions

We show for the first time that DNA methylation in metformin transporter genes in the human liver is different according to diabetes medication and associates with gene expression. Lower methylation in SLC22A1, SLC22A3, and SLC47A1 in the liver was associated with metformin therapy, lower glucose levels, and lower BMI. This study shows a novel mechanism of metformin which regulates the epigenetic pattern of the key metformin transporters in the human liver.

Methods

Study participants and clinical characteristics

This study includes 95 obese participants (64% women, age 49.5 ± 7.7 years, 35 with T2D and 26 subjects with NASH who were recruited from the Kuopio Obesity Surgery Study (Additional file 1: Table S3). The participants underwent Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery and liver biopsies were collected during the operation. Informed consent was obtained and the study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Northern Savo Hospital District [30, 31]. All experiments were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Fasting blood samples were drawn on the morning of the surgery, and plasma glucose and serum insulin were analyzed as published elsewhere [32]. Data regarding body weight, height, and presence of diabetes, simple steatosis or NASH were also collected [32]. Three diabetic patients who did not receive any diabetes medication and 30 T2D patients who were taking metformin or insulin plus metformin were considered for the analyses (Additional file 1: Table S1). Among these, eight subjects were also on other oral diabetes medication (Sitagliptin or Glimepiride). In addition, 60 non-diabetic subjects were included in some analyses.

DNA methylation analysis

DNA methylation was assessed in all CpG sites annotated to three metformin transporter genes on the Infinium HumanMethylation450 BeadChip from Illumina, including 13 sites annotated to SLC22A1, 23 sites annotated to SLC22A3 and 24 sites annotated to SLC47A1. The genome-wide DNA methylation data from the human liver has previously been published and included 95 participants whose characteristics are presented in Additional file 1: Table S3 [20].

Gene expression analysis

mRNA expression of SLC22A1, SLC22A3, and SLC47A1 was analyzed in the human liver using HumanHT-12 Expression BeadChip (Illumina). mRNA expression was assessed in the liver from a subset of subjects (42 participants) due to the limited size of human liver biopsies, available amounts of liver RNA, and resources [20]. Among these 42 participants, 19 were diabetics of whom 13 were receiving metformin, 5 were on insulin plus metformin therapy, and 1 was not on any diabetes medication. The characteristics of these 42 participants have previously been described [20].

Cell culture experiments

Huh-7 human hepatocellular carcinoma cells were cultured with DMEM, 1.0 g/L glucose plus 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. Cells were treated for 8 h with either 0.5 mM metformin (Sigma-Aldrich), 100 nM insulin, 0.5 mM metformin plus 100 nM insulin, or 24 mM glucose. The treatment time was selected since it has previously been shown that metformin treatment for 8 h in vitro has an effect on gene expression and activates AMPK phosphorylation [33, 34].

Genomic DNA was extracted from cells using DNeasy blood and tissue kit (Qiagen), and DNA methylation was analyzed using PyroSequencing as previously reported [18]. PyroMark Assay Design Software 2.0 (Qiagen) was used to design PyroSequencing primers (Additional file 1: Table S4).

Statistical analyses

Participant’s clinical characteristics were compared according to diabetes medication using the one-way ANOVA test. ANCOVA test was used to assess DNA methylation or gene expression levels according to diabetes medication, followed by post-hoc tests to compare groups. Paired t test was used for in vitro experiments. DNA methylation was correlated to expression levels using Pearson correlations and linear regression models. To assess associations between DNA methylation and glucose levels or BMI, a linear regression model was used. ANCOVA and linear models were adjusted for age, sex, and NASH except for glucose associations where just age and sex were included because there was a high correlation between NASH and glucose levels (P = 0.0029). To separate the effect of medication from NASH on DNA methylation, we analyzed the residuals without including diabetes medication in the model (age, sex, and NASH were included). The residuals did not depend on NASH (P value > 0.05) indicating that NASH and medication likely are independent variables and that the model has been well corrected for NASH. FDR was used to correct for multiple testing. Statistical analyses were performed using STATA v12.0 (StataCorp).

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- NASH:

-

Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis

- T2D:

-

Type 2 diabetes

References

Bao B, Azmi AS, Ali S, Zaiem F, Sarkar FH. Metformin may function as anti-cancer agent via targeting cancer stem cells: the potential biological significance of tumor-associated miRNAs in breast and pancreatic cancers. Ann Transl Med. 2014;2:59.

Chen EC, Liang X, Yee SW, Geier EG, Stocker SL, Chen L, et al. Targeted disruption of organic cation transporter 3 attenuates the pharmacologic response to metformin. Mol Pharmacol. 2015;88:75–83.

Shu Y, Sheardown SA, Brown C, Owen RP, Zhang S, Castro RA, et al. Effect of genetic variation in the organic cation transporter 1 (OCT1) on metformin action. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1422–31.

Toyama K, Yonezawa A, Masuda S, Osawa R, Hosokawa M, Fujimoto S, et al. Loss of multidrug and toxin extrusion 1 (MATE1) is associated with metformin-induced lactic acidosis. Br J Pharmacol. 2012;166:1183–91.

Tsuda M, Terada T, Mizuno T, Katsura T, Shimakura J, Inui K. Targeted disruption of the multidrug and toxin extrusion 1 (mate1) gene in mice reduces renal secretion of metformin. Mol Pharmacol. 2009;75:1280–6.

Wang DS, Jonker JW, Kato Y, Kusuhara H, Schinkel AH, Sugiyama Y. Involvement of organic cation transporter 1 in hepatic and intestinal distribution of metformin. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;302:510–5.

Dujic T, Zhou K, Donnelly LA, Tavendale R, Palmer CN, Pearson ER. Association of organic cation transporter 1 with intolerance to metformin in type 2 diabetes: a GoDARTS study. Diabetes. 2015;64:1786–93.

Todd JN, Florez JC. An update on the pharmacogenomics of metformin: progress, problems and potential. Pharmacogenomics. 2014;15:529–39.

Becker ML, Visser LE, van Schaik RH, Hofman A, Uitterlinden AG, Stricker BH. Genetic variation in the multidrug and toxin extrusion 1 transporter protein influences the glucose-lowering effect of metformin in patients with diabetes: a preliminary study. Diabetes. 2009;58:745–9.

Jablonski KA, McAteer JB, de Bakker PI, Franks PW, Pollin TI, Hanson RL, et al. Common variants in 40 genes assessed for diabetes incidence and response to metformin and lifestyle intervention in the diabetes prevention program. Diabetes. 2010;59:2672–81.

Zhou K, Donnelly LA, Kimber CH, Donnan PT, Doney AS, Leese G, et al. Reduced-function SLC22A1 polymorphisms encoding organic cation transporter 1 and glycemic response to metformin: a GoDARTS study. Diabetes. 2009;58:1434–9.

Nies AT, Koepsell H, Winter S, Burk O, Klein K, Kerb R, et al. Expression of organic cation transporters OCT1 (SLC22A1) and OCT3 (SLC22A3) is affected by genetic factors and cholestasis in human liver. Hepatology. 2009;50:1227–40.

Chen L, Hong C, Chen EC, Yee SW, Xu L, Almof EU, et al. Genetic and epigenetic regulation of the organic cation transporter 3, SLC22A3. Pharmacogenomics J. 2013;13:110–20.

Schaeffeler E, Hellerbrand C, Nies AT, Winter S, Kruck S, Hofmann U, et al. DNA methylation is associated with downregulation of the organic cation transporter OCT1 (SLC22A1) in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Genome Med. 2011;3:82.

Schaefer O, Ohtsuki S, Kawakami H, Inoue T, Liehner S, Saito A, et al. Absolute quantification and differential expression of drug transporters, cytochrome P450 enzymes, and UDP-glucuronosyltransferases in cultured primary human hepatocytes. Drug Metab Dispos. 2012;40:93–103.

Otsuka M, Matsumoto T, Morimoto R, Arioka S, Omote H, Moriyama Y. A human transporter protein that mediates the final excretion step for toxic organic cations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:17923–8.

Bacos K, Gillberg L, Volkov P, Olsson AH, Hansen T, Pedersen O, et al. Blood-based biomarkers of age-associated epigenetic changes in human islets associate with insulin secretion and diabetes. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11089.

Dayeh T, Volkov P, Salo S, Hall E, Nilsson E, Olsson AH, et al. Genome-wide DNA methylation analysis of human pancreatic islets from type 2 diabetic and non-diabetic donors identifies candidate genes that influence insulin secretion. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:e1004160.

Nilsson E, Jansson PA, Perfilyev A, Volkov P, Pedersen M, Svensson MK, et al. Altered DNA methylation and differential expression of genes influencing metabolism and inflammation in adipose tissue from subjects with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2014;63:2962–76.

Nilsson E, Matte A, Perfilyev A, de Mello VD, Kakela P, Pihlajamaki J, et al. Epigenetic alterations in human liver from subjects with type 2 diabetes in parallel with reduced Folate levels. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100:E1491–501.

Schwenk RW, Vogel H, Schurmann A. Genetic and epigenetic control of metabolic health. Mol Metab. 2013;2:337–47.

Zhong T, Men Y, Lu L, Geng T, Zhou J, Mitsuhashi A, et al. Metformin alters DNA methylation genome-wide via the H19/SAHH axis. Oncogene. 2017;36:2345–54.

Kohli RM, Zhang Y. TET enzymes, TDG and the dynamics of DNA demethylation. Nature. 2013;502:472–9.

Ivanov M, Kals M, Kacevska M, Barragan I, Kasuga K, Rane A, et al. Ontogeny, distribution and potential roles of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in human liver function. Genome Biol. 2013;14:R83.

Yang Q, Liang X, Sun X, Zhang L, Fu X, Rogers CJ, et al. AMPK/alpha-ketoglutarate axis dynamically mediates DNA demethylation in the Prdm16 promoter and brown adipogenesis. Cell Metab. 2016;24:542–54.

Martin-Castillo B, Vazquez-Martin A, Oliveras-Ferraros C, Menendez JA. Metformin and cancer: doses, mechanisms and the dandelion and hormetic phenomena. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:1057–64.

Jones PA. Functions of DNA methylation: islands, start sites, gene bodies and beyond. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13:484–92.

Volkov P, Bacos K, Ofori JK, Esguerra JL, Eliasson L, Ronn T, et al. Whole-genome bisulfite sequencing of human pancreatic islets reveals novel differentially methylated regions in type 2 diabetes pathogenesis. Diabetes. 2017;66:1074–85.

Wagner JR, Busche S, Ge B, Kwan T, Pastinen T, Blanchette M. The relationship between DNA methylation, genetic and expression inter-individual variation in untransformed human fibroblasts. Genome Biol. 2014;15:R37.

Kaminska D, Hamalainen M, Cederberg H, Kakela P, Venesmaa S, Miettinen P, et al. Adipose tissue INSR splicing in humans associates with fasting insulin level and is regulated by weight loss. Diabetologia. 2014;57:347–51.

Mannisto VT, Simonen M, Soininen P, Tiainen M, Kangas AJ, Kaminska D, et al. Lipoprotein subclass metabolism in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. J Lipid Res. 2014;55:2676–84.

Rantakokko P, Mannisto V, Airaksinen R, Koponen J, Viluksela M, Kiviranta H, et al. Persistent organic pollutants and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in morbidly obese patients: a cohort study. Environ Health. 2015;14:79.

Luizon MR, Eckalbar WL, Wang Y, Jones SL, Smith RP, Laurance M, et al. Genomic characterization of metformin hepatic response. PLoS Genet. 2016;12:e1006449.

Stephenne X, Foretz M, Taleux N, van der Zon GC, Sokal E, Hue L, et al. Metformin activates AMP-activated protein kinase in primary human hepatocytes by decreasing cellular energy status. Diabetologia. 2011;54:3101–10.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Swegene Center for Integrative Biology at Lund University Genomics Facility for help with the DNA methylation and mRNA expression analyses. We thank Ashok Matte for help with DNA extraction.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the Swedish Research Council, Region Skåne (ALF), Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation, EFSD/Lilly, The Swedish Diabetes foundation, Påhlsson Foundation, EXODIAB and Linné grant (B31 5631/2006). This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement no. 706081 (EpiHope).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SG designed and performed the experiments and statistical analyses and wrote the manuscript. AP performed the computational analyses. VM and VDdM collected the clinical data. EN analyzed the data. JP designed the study and collected the clinical data. CL designed the study and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants, and the study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Northern Savo Hospital District (54/2005, 104/2008, and 27/2010). All experiments were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Clinical characteristics of the 33 type 2 diabetic patients according to drug treatment and of 60 non-diabetic subjects. Table S2. Average and promoter DNA methylation according to diabetes medication, first comparing other oral medication such as Sitagliptin or Glimepiride + metformin to only metformin therapy, and second excluding all subjects that were receiving Sitagliptin or Glimepiride. Table S3. Clinical characteristics of subjects from the Kuopio Obesity Surgery Study. Table S4. DNA sequences of the primers used for pyrosequencing. Figure S1. DNA methylation of SLC22A3 and SLC47A1 in hepatocytes cultured in vitro after 8 h of metformin (0.5 mM), insulin plus metformin, insulin (100 nM) or glucose treatment in Huh-7 cells (n = 4). Means and standard deviations are shown, and paired t test was used for the analysis. Figure S2. Gene expression levels of the three metformin transporter genes in the human liver (A) (n = 42); gene expression of transporter genes according to diabetes medication after adjusting for age, sex and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) (B). ns: no significant. (DOCX 213 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

García-Calzón, S., Perfilyev, A., Männistö, V. et al. Diabetes medication associates with DNA methylation of metformin transporter genes in the human liver. Clin Epigenet 9, 102 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13148-017-0400-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13148-017-0400-0