Abstract

Background

Herpes simplex virus (HSV) encephalitis is the most common sporadic cause of encephalitis with significant morbidity and mortality that is drastically reduced by early antiviral treatment.

Case presentation

We report a 37 year old woman, 33 weeks pregnant, who presented with seizures due to proven HSV-1 encephalitis, and who had had a previous episode of probable viral encephalitis aged 14 years. She was successfully treated with aciclovir on both occasions and, in the latter, went on to deliver a healthy infant. This case is compared with 17 cases of HSV encephalitis in pregnancy in the literature identifying a predominance in the late 2nd and 3rd trimesters, perhaps in part due to immunological changes in pregnancy. The clinical presentation is also compared with non-pregnant patients with HSV encephalitis in the largest prospective UK and European studies. We also present practical advice on management from recent national guidelines.

Conclusion

When pregnant women present with new seizures, headache, impaired consciousness or altered behaviour urgent investigation is required to identify common diagnoses, such as eclampsia, venous sinus thrombosis and metabolic disturbances. Nevertheless, viral encephalitis is a very treatable cause of this presentation with potentially serious complications if missed, and may be more common in latter stages of pregnancy. Encephalitis should not be discounted if the patient is afebrile, has a normal Glasgow coma score, or the cerebrospinal fluid white cell count is only slightly elevated, as these features are well recognised in viral encephalitis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Herpes simplex virus is the most common sporadic cause of encephalitis, with the majority of cases due to HSV type-1. Early investigation and treatment is critical, as mortality is reduced from >70% to <20-30% [1,2]. HSV encephalitis has been described in pregnancy but little is known about how the clinical presentation and outcome compare between this group and those with HSV encephalitis outside of pregnancy.

Methods

To assess if the clinical presentation and outcome in pregnant patients differs from non-pregnant patients, we first describe a case of HSV encephalitis in pregnancy. In addition, a Medline search for previous case reports of HSV encephalitis in pregnant women in English (between 1972 and 2013) was performed, using the search terms herpes simplex encephalitis and pregnancy. Cases with HSV type 1 and type 2 were identified, but were only included if they met established clinical case definitions for encephalitis, namely encephalopathy (altered consciousness that persisted for longer than 24 hours, including lethargy, irritability, or a change in personality and behaviour) and two or more of the following: fever or history of fever (≥38°C) during the presenting illness; seizures and/or focal neurological findings (with evidence of brain parenchyma involvement); CSF pleocytosis (>4cells/μL); electroencephalographic findings indicative of encephalitis; and abnormal results of neuroimaging (computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging) suggestive of encephalitis [3,4]. Data from these cases were compared with those from the two largest multicentre prospective studies of HSV encephalitis in the UK and Europe; the authors of the UK paper were approached to provide additional raw data when required [4,5]. Univariate analysis was performed using the chi-squared Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and the Mann–Whitney U test for continuous data using SPSS 2012©. A Glasgow coma score (GCS) of <8 was defined as coma and statistical significance as a p value of <0.05.

Case presentation

A 37 year old right-handed woman, who was 33 weeks pregnant (gravida 5, para 3), presented following a first seizure. She had a preceding 10-day history of diarrhoea, vomiting, photophobia and severe headache, which woke her up from sleep and was exacerbated by coughing. There was no recent travel or head injury. A witness reported that she had visual hallucinations, followed by an episode of inappropriate laughter and within minutes a secondary generalised seizure: her right arm moved over her chest and her head deviated to the right, followed by her whole body becoming stiff, with clonic movements of all limbs. She became cyanosed, bit her tongue, had urinary incontinence and was unrousable. This lasted for approximately five minutes, followed by post-ictal drowsiness for two hours.

At presentation to the local teaching hospital she was apyrexial, had a GCS of 15/15, and normal cardio-respiratory and neurological examinations. She was not hypertensive and urinalysis did not demonstrate proteinuria. Her full blood count, renal, liver and bone profiles were normal, the erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 39 (reference range 5–15) mm/hr and C-reactive protein was 6 (<10) mg/L. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and venography of the brain on day one were normal. Oral carbamazepine was commenced and, following a second tonic-clonic seizure 16 hours after admission, oral clobazam was added.

A lumbar puncture (LP) demonstrated an opening pressure of 14 (reference range 7–18) cm, CSF white cells count (WCC) 10 (<5) ×106/L, with predominance of immature neutrophils (percentage not known), red cell count (RCC) 2 (0–10) ×106/L, protein 0.23 (0.15-0.4) g/L, and CSF glucose 3.6 (2.8-4.2) mmol/L, 67% of blood glucose. No organisms were seen, and oligoclonal bands were negative. On receipt of these results, intravenous aciclovir was commenced; approximately 25 hours after admission.

On day two she developed fluctuating confusion, abnormal behaviour and a temperature of 37.8°C. Her GCS deteriorated to 11/15 (eyes opening to speech, incomprehensible sounds and obeying commands), and she had a positive Babinski’s sign on the right. She was given intravenous phenytoin, for clinically suspected non-convulsive status epilepticus.

The patient had previously been admitted, when aged 14, with acute headache, confusion, vomiting, photophobia and diplopia. LP demonstrated a CSF protein of 0.8 (0.15-0.4) g/L, glucose 3.6 (2.8-4.2) mmol/L, WCC 1 (0–5) ×106/mm3, RCC 38 (0–10) ×106/L, and no organisms were seen. Viral polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis and antibody testing were not available. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the brain demonstrated small ventricles with early cerebral oedema. A full course of intravenous aciclovir was given for presumed HSV encephalitis. She made a full and uneventful recovery.

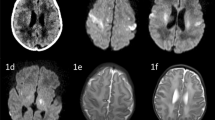

In the current admission, CSF PCR returned positive for HSV type-1 and negative for HSV type-2, varicella zoster virus and enterovirus. Electroencephalography (EEG) showed left fronto-temporal epileptiform discharges, and repeat MRI on day three showed classic changes of herpes simplex encephalitis with high signal on diffusion weighted imaging of the left temporal pole and left insular cortex.

The aciclovir was stopped after 16 days, following repeat CSF HSV-1 PCR testing negative. Foetal growth scans and foetal heart rate monitoring were normal throughout. An elective caesarean section at 39 weeks was undertaken with no complications, and a healthy boy, of 3.725 kg, was delivered. The neonate was not given aciclovir. A repeat EEG prior to discharge showed marked improvement albeit with some residual slowing. Phenytoin and clobazam were gradually tapered off and carbamazepine continued. At six month follow-up the patient is well with no seizure recurrence and the child was healthy.

Results

21 cases were identified, four were excluded; two as they contained cases of metabolic encephalopathy and disseminated HSV-2 infection without encephalitis, and two had no definite proof of HSV infection [6-9]. Therefore, 17 cases were included in the analysis and these are summarised in Table 1 [7,10-23]. The majority of cases occurred in the later stages of pregnancy, with 11 (61) in the 3rd trimester, 6 (33%) in the 2nd trimester and only 1 (6%) in the 1st trimester.

In this case, the patient was afebrile and the CSF white cell count was only slightly raised. In comparison to the largest prospective UK cohort of 38 patients and the European cohort of 98 patients, the proportion of patients during pregnancy reported in the literature who were afebrile on admission was similar (Table 2). The mean WCC was also similar between the groups. In this case, although there had been a preceding seizure, at the time of initial clinical clerking assessment the GCS was normal. Of the cases in the literature at presentation, none of the eight pregnant patients in whom the GCS was available had GCS <8, whereas this has previously been seen in 24% of the general mixed sex population with HSV-1 encephalitis and 9% of adults with HSV encephalitis overall [4,5]. This may reflect an earlier presentation in pregnant patients, as the median (range) days of symptoms prior to admission was shorter for pregnant patients, although this was not statistically significant (3 [0–10] vs 6.5 [0–30], p = 0.35). There are limitations in the interpretation of this data as the case reports are from a wide time period and there is variability in the data that is presented within them. What would have been ideal, but was not possible due to the limitations of the published data, would have been to compare the time from onset of symptoms, to onset of coma between pregnant patients with HSV1 encephalitis and an age and sex-matched cohort with HSV1 encephalitis.

The outcome of pregnant patients treated for HSV encephalitis appears not to be statistically different to that in the general population. In those patients treated with aciclovir (n = 15), only 1 women (7%), and 1 foetus, died with on-going disability for 4 (27%) of the surviving women. Nevertheless, of those not given aciclovir (n = 6), 4 (67%) women and 3 (50%) foetuses died. In other studies, mortality in HSV encephalitis treated with aciclovir has been reported as 11% – 15%, without a significant difference in outcome between sexes, although this may reflect publication bias [4,5].

Discussion

Herpes simplex virus is the most common cause of sporadic viral encephalitis with 90% of cases being due to type-1 [1,4]. It usually presents as a concurrent or antecedent febrile or coryzal illness with headache, impaired cognition, reduced consciousness, changes in personality and behaviour and seizures.

This patient had proven HSV-1 encephalitis when pregnant aged 37, with an episode of encephalitis aged 14 which was of uncertain aetiology due to investigatory limitations at the time of intitial presentation in childhood, although HSV would be the most common cause and the patient was treated for presumed HSV encephalitis. Therefore, this may possibly represent a late relapse of HSV-1 encephalitis during pregnancy, which has not previously been reported, although more thorough investigation at the time of the childhood illness would be required to establish this. Relapse of HSV-1 encephalitis is rare, but recognised, and can be either early, due to suboptimal treatment or post-infectious immune process, or late, with latencies previously reported of up to 8.5 years [2,24].

During pregnancy, women may be at an increased risk of certain infections, and also increased risk of severe manifestations of infection [25-27]. There are many complex immunological adaptations during in pregnancy, to prevent rejection of the ‘foetal allograft’, which contains paternal antigens [25,26]. Oestrogens and progesterones rise during pregnancy, are highest in the late 2nd and 3rd trimesters, and are thought to modulate an immunological shift, in both the cell-mediated and humoural systems [25,26]. Interestingly the vast majority of cases of HSV encephalitis identified in pregnancy occurred in the 3rd trimester and, to a lesser extent in the 2nd trimester, with only 2 occurring in the 1st trimester. This may, however, relate to lower recognition of pregnancy during the first trimester.

In pregnant women presenting with seizures, headache, or altered behaviour, in addition to viral encephalitis the differential diagnosis includes and number of other structural and metabolic causes which must be excluded. Hyperemesis gravidarum in early pregnancy results in excessive vomiting producing electrolyte imbalance, which, if severe, may provoke seizures [28]. Eclampsia refers to seizures or coma as severe complications of pre-eclapmsia; this is identified by hypertension and proteinuria. Pregnancy increases blood viscosity and the risk of thrombosis; therefore if seizures were preceded by headache, especially if with features of raised intracranial pressure, then an MR venogram should be performed. Further differential diagnosis includes acute hepatitis, malaria, ischaemic stroke, or acute intermittent porphyria [29]. The UK guideline for the management of suspected viral encephalitis recommend intravenous aciclovir as soon as possible if the CSF or MRI findings suggest viral encephalitis, or within 6 hours if these results are not available (Figures 1 and 2) [1,27]. There are no specific guidelines for management of viral encephalitis in pregnancy, but there is accumulating evidence that aciclovir is safe in pregnancy and is not associated with an increase in birth defects [30]. As mortality in HSV encephalitis is reduced from >70% to <20-30% with aciclovir, and delay in starting treatment is associated with a worse outcome, treatment should be started promptly in all patients with suspected HSV encephalitis [1,27,31]. In pregnant patients with seizures the lowest effective dose of anti-epileptic drugs is preferable, avoiding polytherapy and particularly potentially teratogenic drugs [32]. Nevertheless, the aim should be seizure freedom as there is a risk to the foetus during tonic-clonic seizures [32]. There is currently no evidence to support the use of anti-epileptic drugs as primary prophylaxis in viral encephalitis, and no evidence to direct secondary prophylaxis [33,34].

Algorithm for the management of patients with suspected viral encephalitis. (Reprinted from Journal of Infection, 64(4): 347–73, Solomon T, Michael BD, Smith PE, et al. Management of suspected viral encephalitis in adults - Association of British Neurologists and British Infection Association National Guidelines, Copyright 2012, with permission from Elsevier) [1].

We identified that the cases of HSV encephalitis reported in pregnancy often did not have a significantly impaired GCS and that this may reflect an earlier presentation of some patients in this group. However, there are limitations in the interpretation of these data as the case reports are from a wide time period and there is variability in the data that is presented within them. What would have been ideal, but was not possible due to the limitations of the published data, would have been to compare the time from onset of symptoms, to onset of coma between pregnant patients with HSV1 encephalitis and an age and sex-matched cohort with HSV1 encephalitis.

Conclusion

Urgent investigation for common diagnoses, such as eclampsia, venous sinus thrombosis and metabolic disturbance is required when pregnant women present with headaches, new seizures, and changes in cognition or behaviour. HSV encephalitis is an additional treatable cause of this presentation, with potentially devastating consequences if missed, and may be more common in the late 2nd and 3rd trimesters. Importantly, HSV encephalitis should not be discounted in pregnant patients presenting with a normal or near-normal GCS, which can be seen in all patients with HSE, but may be more common during pregnancy; possibly due to the altered immune response, or earlier presentation. In future, where possible, pregnant women should not be excluded from studies of immunological responses during viral encephalitis.

Consent

We have obtained the patient’s full consent for publication. Consent for anonymous publication of the index case in this report was obtained by the authors, consent for the additional cases in this series is provided with the individual case publications.

Abbreviations

- HSV:

-

Herpes Simplex Virus

- GCS:

-

Glasgow Coma Score

- CSF:

-

Cerebrospinal Fluid

- MRI:

-

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

- LP:

-

Lumbar Puncture

- WCC:

-

White cell count

- RCC:

-

Red cell count

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- EEG:

-

Electroencephalogram

References

Solomon T, Michael BD, Smith PE, Sanderson F, Davies NW, Hart IJ, et al. Management of suspected viral encephalitis in adults – association of British Neurologists and British Infection Association National Guidelines. J Infect. 2012;64:347–73.

Whitley RJ, Gnann JW. Viral encephalitis: familiar infections and emerging pathogens. Lancet. 2002;359:507–13.

Michael BD, Sidhu M, Stoeter D, Roberts M, Beeching NJ, Bonington A, et al. The epidemiology and management of adult suspected central nervous system infections - a retrospective cohort study in the NHS Northwest Region. Q J Med. 2010;103(10):749–5.

Granerod J, Ambrose HE, Davies NW, Clewley JP, Walsh AL, Morgan D, et al. Causes of encephalitis and differences in their clinical presentations in England: a multicentre, population-based prospective study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010;10:835–44.

Raschilas F, Wolff M, Delatour F, Chaffaut C, De Broucker T, Chevret S, et al. Outcome of and prognostic factors for herpes simplex encephalitis in adult patients: results of a multicentre study. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;35(3):254–60.

King RL. Herpes simplex encephalitis in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1979;135:1114–5.

Roman-Campos G, Navarro De Roman LI, Toro G, Vergara I. Herpes encephalitis in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynaecol. 1979;135:158–9.

Young EJ, Killam AP, Green FJ. Disseminated herpes virus infection. J Amer Med Assoc. 1976;235:2731–3.

Klein NA, Mabie WC, Shaver DC, Latham PS, Adamec TA, Pinstein ML, et al. Herpes simplex virus hepatitis in pregnancy: two patients successfully treatment with aciclovir. Gastroenterology. 1991;100(1):239–44.

Pascal J, Perbet S, Bourdel N, Da Ines D, Tran X, Chartier C, et al. Management of HSV-1 encephalitis due to reactivation of HSV-1 during later pregnancy. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2012;21:364–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijoa.2012.05.004.

Mesker AJ, Bon GG, de Gans J, de Krujik JR. Case report: a pregnant woman with herpes simplex encephalitis successfully treated with dexamethasone. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2011;154:231–2.

Sellner J, Buonomano R, Nedeltchev K, Findling O, Schroth G, Surbek DV, et al. A case of maternal herpes simplex virus encephalitis during later pregnancy. Nat Clin Pract Neurol. 2009;5:51–6.

Piskin N, Akduman D, Aydemir H, Celebi G, Oztoprak N. Herpes simplex virus encephalitis in pregnancy. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2008;21:421–3.

Gunduz A, Beskardes AF, Kutlu A, Ozkara C, Karaagac N, Yeni SN. Herpes encephalitis as a cause of nonconvulsive status epilepticus. Epileptic Disord. 2006;8:57–60.

Godet C, Beby-Defaux A, Agius G, Pourrat O, Robert R. Maternal herpes simplex virus type 2 encephalitis following cesarean section. J Infect. 2003;47:174–5.

Dupuis O, Audibert F, Fernandez H, Frydman R. Herpes simplex virus encephalitis in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;94:810–2.

Luby JP. Southwestern internal medicine conference: infections of the central nervous systems. Am J Med Sci. 1992;304:379–91.

Anteby E, Reches A, Lavy Y, Yagel S. Fetal serology in maternal HSV encephalitis. Prenat Diagn. 1992;12:855–6.

Frieden FJ, Ordorica SA, Goodgold AL, Hoskins IA, Silverman F, Young BK. Successful pregnancy with isolated herpes simplex virus encephalitis: case report and review of the literature. Obstet Gynecol. 1990;75:511–3.

Besser R, Vogt T, Thömke F. Successful treatment of HSV encephalitis during pregnancy. Neurology. 1989;39:748.

Hankey GJ, Bucens MR, Chambers JS. Herpes simplex encephalitis in third trimester of pregnancy: successful outcome for mother and child. Neurology. 1987;37:1534–7.

Berger SA, Weinberg M, Treves T, Sorkin P, Geller E, Yedwab G, et al. Herpes encephalitis during pregnancy: failure of acyclovir and adenine arabinoside to prevent neonatal herpes. Isr J Med Sci. 1986;22:41–4.

Anderson JM, Nicholls MW. Herpes encephalitis in pregnancy. Br Med J. 1972;1:632.

Spiegel R, Miron D, Yodko H, Lumelsky D, Habib A, Horovitz Y. Late relapse of herpes simplex virus encephalitis in a child due to reactivation of latent virus: clinicopathological report and review. J Child Neurol. 2008;23:344–8.

Chen SJ, Liu YL, Sytwu HK. Immunologic regulation in pregnancy: from mechanism to therapeutic strategy for immunomodulation. Clin Dev Immunol. 2012;2012:258391.

Robinson DP, Klein SL. Pregnancy and pregnancy-associated hormones alter immune responses and disease pathogenesis. Horm Behav. 2012;62:263–71.

Kneen R, Michael BD, Menson E, Mehta B, Easton A, Hemingway C, et al. Management of suspected viral encephalitis in children – association of British Neurologists and British infection association national guidelines. J Infect. 2012;64:449–77.

Rahuldeo J, Sushil K, Anupam A, Pragati T. Ventricular tachycardia and seizure in hyperemesis gravidarum. J Obstet Gynecol India. 2010;60(4):339–40.

Beach RL, Kaplan PW. Seizures in pregnancy: diagnosis and management. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2008;83:259–71. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7742(08)00015-9.

Kang SH, Chua-Gocheco A, Bozzo P, Einarson A. Safety of antiviral medication for hte treatment of herpes during pregnancy. Can Fam Physician. 2011;57:427–8.

Tunkel AR, Glaser CA, Bloch KC, Sejvar JJ, Marra CM, Roos KL, et al. The management of encephalitis: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:303–27.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. The epilepsies: the diagnosis and management of the epilepsies in adults and children in primary and secondary care. Clinical guidelines, CG137. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence; 2012.

Michael BD, Solomon T. Seizures and encephalitis: clinical features, management, and potential pathophysiologic mechanisms. Epilepsia. 2012;53:63–71.

Pandey S, Rathore C, Michael BD. Antiepileptic drugs for the primary and secondary prevention of seizures in viral encephalitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013:CD010247. doi:10.1002/14651858.

Acknowledgements

BDM is an NIHR Academic Clinical Lecturer and received support as part of an NIHR Doctoral Research Fellowship. TS received support from the MRC and NIHR PHRU. The authors have not conflicts of interest to declare. The research materials supporting this publication can be accessed by contacting benedict.michael@liv.ac.uk.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

KD participated in the design of the manuscript, performed the literature search and drafted the manuscript. BDM also participated in the design of the manuscript, drafted the manuscript, reviewed the literature, and performed statistical analysis. BZ obtained the patients consent. BW, AK, RB and TS all participated in the design and composition of the manuscript. All authors made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; and final approval of the version to be published.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Dodd, K.C., Michael, B.D., Ziso, B. et al. Herpes simplex virus encephalitis in pregnancy - a case report and review of reported patients in the literature. BMC Res Notes 8, 118 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-015-1071-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-015-1071-6