Abstract

Malaria transmission persists despite the scale-up of interventions such as long-lasting insecticide-treated nets (LLINs) and indoor residual spraying (IRS). Understanding the entomological drivers of transmission is key for the design of effective and sustainable tools to address the challenge. Recent research findings indicate a shift in vector populations from the notorious Anopheles gambiae (s.s.) as a dominant vector to other species as one of the factors contributing to the persistence of malaria transmission. However, there are gaps in the literature regarding the minor vector species which are increasingly taking a lead role in malaria transmission. Currently, minor malaria vectors have behavioural plasticity, which allows their evasion of vector control tools currently in use. To address this, we have reviewed the role of Anopheles merus, a saltwater mosquito species that is becoming an important vector of malaria transmission along the East and Southern African coast. We performed a literature review from PubMed and Google Scholar and reviewed over 50 publications relating to An. merus's bionomics, taxonomy, spatial-temporal distribution and role in malaria transmission. We found that An. merus is an important vector of malaria and that it contributes to residual malaria transmission because of its exophilic tendencies, insecticide resistance and densities that peak during the dry seasons as the freshwater mosquitoes decline. Spatial and temporal studies have also shown that this species has increased its geographical range, densities and vectorial capacity over time. In this review, we highlight the resting behaviour and breeding habitats of this mosquito, which could be targeted for surveillance studies and control interventions.

Graphical Abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Malaria continues to be a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in Africa, especially in sub-Saharan Africa [1]. In 2018, over 400,000 malaria deaths were reported globally of which 67% were reported in children under 5 years [1]. Global malaria control has historically been undertaken to prevent new infections and to ensure that malaria transmission is curtailed. Malaria control and eradication efforts have gone through different phases from which several lessons have been learnt. The initial campaigns in the early twentieth century were country-specific and were not well funded. For example, in 1939–1940, Fred Soper of the Rockefeller Foundation led vigorous larval source management (LSM) activities using the dust larvicide, Paris green (copper(II) acetoarsenite), leading to the elimination of Anopheles gambiae from Brazil [2]. LSM was effective but tedious in its implementation, which necessitated the discovery and deployment of other measures to control mosquito vectors and to diagnose and treat malaria infections [3, 4]. During World War II (WWII), much of the previously achieved gains in vector control were lost because of the shift of investments to the war, destruction of infrastructure and the displacement of people. After the end of WWII, world bodies such as the United Nations (UN) and the World Health Organisation (WHO) were created to pursue world security issues and coordinate health-related issues respectively. To ensure control and eradication of malaria post-WWII, WHO, during the 8th World Health Assembly in 1954 [5], resolved to have a consolidated effort to eradicate malaria globally, which was implemented between 1955 and 1972 [6,7,8]. Several attempts to undertake indoor residual spraying (IRS) were made especially between 1955 and 1969, for instance, the Pare-Taveta Malaria Control Scheme on the Kenyan and Tanzanian border, which was carried out by the East Africa Institute of Malaria and Vector Borne Diseases (EA-MVBD) and the WHO [7]. This large-scale trial undertook residual spraying (IRS) with Dieldrin and DDT in the Taveta sub-district of Kenya and the Pare district of Tanzania. During this expansive malaria control programme, entomological and parasitological surveillance systems were deployed to monitor the decline in malaria cases and malaria transmission. The programme's impact analysis showed that human mortality among all age groups was halved during the spraying campaign. The entomological surveys showed that An. funestus was eliminated by the IRS programme while the An. gambiae population was reduced sevenfold, and sporozoites were undetectable in the infected population [9]. After the collapse of the first Global Malaria Eradication Program, malaria control efforts were undertaken through interventions against the disease causing the malaria parasite, such as the use of chloroquine for case management [10]. However, treatment failures were reported due to the development of chloroquine resistance [11]. The current global malaria control initiative was re-established in the late 1990s through consulted leadership of the WHO, with the establishment of consolidated efforts such as Roll Back Malaria (RBM). These WHO-mediated efforts changed the malaria control paradigm and ensured malaria control was implemented through a programmatic approach. During this phase, several multi-faceted strategies were implemented targeting enhancing partnerships, government/political support such as the Abuja Declaration by the continent’s heads of state [12], control of vectors (scale-up of ITN/LLINs, IRS), case detection, case management, major campaigns in advocacy communication and social mobilization for behaviour change [13, 14]. At the national level, malaria control efforts were managed through National Malaria Control Programmes (NMCPs), which worked closely with WHO. These efforts have led to a significant decline in malaria morbidity and mortality, especially between 2000 and 2015 [15]. Although malaria-endemic countries are currently faced with an upsurge in malaria as a result of residual transmission [1, 16], there is a renewed effort to contain malaria, especially towards pre-elimination and elimination phases as outlined by the WHO Global Technical Strategy for Malaria 2016–2030 [17].

Over the decades, vector control has become a major pillar in the fight against malaria and has mainly been done through scaling up the use of LLINs and IRS. The indoor-based chemical control interventions resulted in a tremendous decline in malaria prevalence and incidence especially between 2000 and 2015 [15]. However, malaria vectors have responded via behavioural modifications, including changing their feeding and resting patterns [7, 8, 18, 19]. Additionally, changes in species composition, which has seen previously minor malaria species become more dominant (species replacement) [20,21,22], as well as the development and spread of insecticide resistance have all contributed to an increase in malaria incidence post 2015 [23,24,25,26,27].

Traditionally, the dominant vectors of malaria have been An. gambiae (s.s.) and Anopheles funestus, which preferentially feed on humans and reside indoors. Whilst most known interventions focusing on indoor feeding and resting mosquitoes remain effective against the two mosquito species, changes in vector composition and behaviour have seen the decline of An. gambiae (s.s.) and the emergence of new vectors.

Some members of the An. gambiae complex (An. merus) and other species (An. coustani, An. pretoriensis and An. moucheti) that were initially considered as minor malaria vectors have recently been reported to play a leading role in malaria transmission [21, 22, 28, 29]. Behaviour modification to favour outdoor feeding and resting and reliance on blood-meal sources from humans to alternate vertebrates [19, 22] have allowed the new vectors to avoid LLINs that largely target indoor feeding and resting mosquitoes. However, these minor species have been given little attention in malaria research, resulting in a paucity of information about their biology, behaviour and role in disease transmission. As these species gain dominance, this knowledge will be crucial in the design and application of control interventions. This review has focused on the identification methods, bionomics, spatial and temporal distribution and the role in disease transmission of Anopheles merus, which is increasingly becoming an important malaria vector in the East and Southern coastal regions of Africa.

Methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

The electronic databases PubMed and Google Scholar were searched for articles documenting An. merus using the search phrases “Anopheles merus” and “saltwater Anopheles gambiae”. All the documents were screened and assessed to determine whether they had any data on vector densities, breeding sites, vectorial capacity and the coordinates of mosquito collection sites.

Data analysis

Data were extracted from the articles and stored in a Microsoft Excel file. The coordinate data were converted into a similar format (Decimal Degrees) using the Polar Geospatial Center (PGC) Coordinate Converter [30]. Statistical analysis and data visualisation were carried out using the R software, version 3.6.3 [31]. Comparisons between the different mosquito counts were done using the Kruskal-Wallis test [32].

The mosquito population structure in each of the sites was analysed using the following ecological parameters: population abundance (total number of mosquitoes per site), species richness (measure of the number of species per site), species evenness (measure of how homogeneous a community is in terms of abundance of all its species) and species diversity (Shannon-Weiner index, Simpson dominance index and Margalef’s index).

To measure species evenness, the Pielou index was used, which compares the actual diversity values using Shannon-Wiener index to the maximum diversity value. The Pielou index value ranges from 0 to 1, the more the variation in abundance between the different taxa within the community the lower the J value and vice versa [33].

where H’ is the number derived from the Shannon-Wiener diversity index and H max is the maximum possible value of H’, which is derived from the equation:

The Margalef’s index measures only gross species richness [34]. The equation is as follows

where S is the number of species and N is the number of mosquitoes in the collection sites.

The Shannon-Weiner index characterises the diversity of a community by considering the abundance and evenness of species present. The index increases as both the richness and evenness of the community increases. The values range from 0 to 5 [35]. The equation:

where p i is the proportion of individuals belonging to the ith species and S is the number of species.

The Simpson diversity index measures the degree of dominance of an individual mosquito species using the following equation [36]:

where p i is the proportion of individuals belonging to the ith species and S is the total number of species.

Results

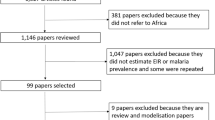

A total of 143 records were found during the initial search with 42 of these being duplicates which were dropped. The abstracts of the remaining records were screened and out of these 70 were retained and the rest removed since inappropriate outcomes were assessed or not in English. The full articles of the remaining documents were screened and out of these we remained with 53 articles which were included in the study, and the data were extracted and are available in Additional file 1. The results of the search strategy are provided in a PRISMA flow chart (Fig. 1).

Identification of An. merus

Initially An. merus was distinguished from other An. gambiae (s.l.) sibling species using a salinity physiological method whereby the hatched larvae were transferred into 75% seawater (23.8 g NaCl/l). Those that died within 2 h were classified as freshwater forms while those that survived for about 6 h were classified as saltwater forms [37]. Later, emphasis was put on taxonomic characteristics with the number of antennal sensilla, palp ratio and shape of the egg being the most reliable way of differentiating saltwater and freshwater An. gambiae. However, these characteristics are concordant with both saltwater species, An. merus and An. melas, except for the ornamentation of tarsi in which An. merus is richer in white scales and in the larval chaetotaxy [38]. The banding patterns of the polyene chromosomes in the ovarian nurse cells of half gravid females have also been used to distinguish the members of the An. gambiae complex [39] although this could not distinguish male mosquitos. Mahon et al. [40] improved on this limitation using allozymes to identify adults of An. gambiae complex regardless of sex and gonotrophic cycle. Hybridization reactions using DNA probes that were species-specific or revealed species-specific restriction enzyme fragments were used [41,42,43]. In 1993, Scott et al. developed a ribosomal DNA- polymerase chain reaction method that identified the members of An. gambiae complex using species-specific nucleotide sequences in the ribosomal intergenic spacers [44]. The advantage of the procedure is that it is sensitive, since most mosquito species have 500 or more copies of ribosomal DNA units and it also utilises both extracted and non-extracted specimens as templates for PCR with a sensitivity of > 95% and > 85% respectively. Recently, advances in proteomics have led to new methods based on whole cells: matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionisation time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS). This approach relies on shrinkage discriminant analysis procedure for differentiating Anopheline species and resolving colony-specific patterns [45]. Near-infrared spectroscopy has also been used for speciation and ageing of An. gambiae (s.s.) and An. arabiensis [46]. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP), which is performed in isothermal conditions, has been used to identify An. gambiae (s.s.) and An. arabiensis. The strength of the LAMP technique is attributed to the high sensitivity and requires simple equipment, making it suitable for field applications with limited access to the more expensive thermocyclers [47].

Species distribution and diversity

The sites from which An. merus were obtained are shown in Fig. 2 and Additional file 1. Furthermore, the proportion of these species in the different sites is illustrated in Fig. 3. Comparisons on the number of species in each site show that the Mahlabaneni region has the most species (An. gambiae, An. merus, An. quadriannulatus and An. arabiensis) while Driekoppies has only one species (An. merus).

Proportions of An. gambiae complex members: An. gambiae (s.s.), An. merus, An. quadriannulatus and An. arabiensis in the different collection sites along the East and Southern African Coast. However, in Changombe, Drain Marie, Grand Baie, L’Isle’d’Ambre, Pemba and Pointe aux Piments, An. gambie (s.l.) were identified using a salt tolerance test and classified as saltwater An. gambiae represented as An. merus in the figure or non-saltwater An. gambiae (An. arabiensis, An. quadriannulatus, An. gambiae), which are represented as An. gambiae

Tests on species richness using Margalef's index show that the richest areas were Mangweni and Oompies Dmg = 1.24 and 1.03 respectively with the least rich areas being Umjindi, Mbombela and Driekoppies (0–0.16) (Fig. 4). Analysis of species diversity: Shannon-Wiener index (H') and Simpson's index (λ) of the different sites were performed. The most diverse areas were Mangweni, Kaole and Mahlabaneni where the range was H' (0.98–1.06) and (λ) (0.59–0.65) (Fig. 4). The least diverse areas were Majajani, Jimbo and Driekoppies. Tests on the homogeneity/evenness of the species in these sites using the Pielou evenness (J) equation show that the most homogeneous sites were Mossuril (0.72), Macome (0.660, Hokwe (0.63) and Umjindi (0.63) with the least even areas being Dindiri, Jimbo and Driekoppies (Fig. 4).

Resting behaviour and biting cycle

Studies in Dar-es-salaam and Pemba have shown that a significant numbers of An. merus leave the house at dawn after feeding the night before [8, 37]. In Jimbo, they came to a similar conclusion as a number of blood-fed An. merus were found outdoors [48]. In Pemba, a large proportion of the mosquitoes collected were resting outdoors under mangrove, mango trees, fallen leaves and coralline rocks and in crab holes [8], whereas in Garithe both indoor and outdoor resting was observed [28]. These similarities in the resting tendencies between indoor and outdoor mosquitoes have been attributed to an intrinsic rhythm or homogeneity in the indoor and outdoor populations [48].

Regarding the biting cycle, two studies came to similar conclusions in South Africa and Kenya. In NKunduse, South Africa, the lowest catches occurred between 18:00 h and 22:00 h, increased significantly between 22:00 h and 02:00 h and then dropped afterwards [49]. In Jimbo village of Kenya, both indoor and outdoor biting activity started to rise at 18:00 h attaining the peak between 24:00 h and 01:00 h and declined gradually to 06:00 h [48]. The normal cycle is however dynamic and is influenced by environmental factors such as wind and temperature [49].

The role of An. merus in malaria transmission

Various studies have documented the role of An. merus as a vector of malaria. In Boane, Mozambique, sporozoite rates of 4.2% for An. merus, 9.6% for An arabiensis and 4.3% for An. funestus were observed . Additionally, comparisons of oocyst rates showed that there was no significant difference among the three mosquito vector species [50]. In Tanzania, sporozoite rates for An. merus have been reported to range between 1.5 and 11.6 [37]. In Ankiliefatra, Madagascar, out of 275 An. gambiae (s.l.) analysed for circumsporozoite antigen, only two female An. merus collected indoors and outdoors were positive [51]. Sporozoite rates ranging between 1 and 29.3% have been reported in Kenya with the highest rates observed in Garithe village [29].

The increase in geographical range and population densities of An. merus has potential for this species to play a significant role in malaria transmission [28, 29, 52, 53]. For example, during the dry seasons the densities of An. merus peak as the freshwater species diminish; therefore, An. merus may potentially sustain malaria transmission during the dry season [20, 54].

An. merus as a vector for lymphatic filariasis

Lymphatic filariasis is a neglected tropical disease which causes painful and disfiguring visible manifestations and permanent disability [55]. By 2018, the disease was a threat to 12% of the global population [56]. The first observation of the transmission of filariasis by An. merus was in Tanzania in 1948 when filarial larvae were detected in 22% of the saltwater forms of An. gambiae compared to 6% in the freshwater forms [37]. In a study carried out in Vyeru village on the Tanzanian coast, comparisons between An. merus and An. gambiae collected both outdoors and indoors showed that An. merus was a more efficient vector of bancroftian filariasis [57]. In Jimbo and Jego villages of Kenya, findings differed from those of Vyeru where An. gambiae was ten times more efficient than An. merus [58]. Additional studies on the importance of An. merus as vectors of transmission of diseases such as lymphatic filariasis are required, given the evidence of their increasing dominance.

Insecticide resistance

Only one study could be found describing the response of An. merus to pyrethroids (deltamethrin), carbamates (bendiocarb) and organochlorines (DDT) as well as this one in South Africa [54]. The species was fully susceptible to deltamethrin and bendiocarb, with 97% mortality on DDT, suggesting possible resistance developing to this insecticide. Since the species is mostly exophilic and therefore less likely to come into contact with the insecticides used for IRS and ITNs, it is suggested that the possible DDT resistance could be driven by selective pressure that may have occurred at the larval stage because of environmental contamination [54].

Larval ecology

The presence of An. merus larvae in a particular habitat is determined by suitable physiochemical and other environmental factors with the most significant determinants being temperature, salinity, algae, conductivity and canopy coverage [59]. Warmer temperatures have been found to accelerate the development of the larvae and proliferation of microorganisms that provide nutrients for the larvae as well as speeding up the decomposition of leaves, debris and algae, which also act as a food source [60,61,62]. For example, the presence of algae in pools has been associated with the presence of An. merus larvae [59]. It has also been shown that algal biomass and abundances and microeukaryote community structure are influenced by larval grazing [63].

Rain has been shown to influence salinity, whereby during the onset of rains, salts deposited at the bottom of semi-permanent breeding sites become dissolved creating favourable breeding salinities; however, long rains dilute the brackish water consequently reducing An. merus densities. As the rains disappear, the semi-permanent breeding sites start evaporating, increasing salinity achieving optimum conditions sustaining increased An. merus densities. However, high salinity levels are associated with reduced mosquito densities [64]. In Dar-es-salaam, the saltwater forms of An. gambiae were shown to be dominant during the dry season (September–August) while the freshwater forms were dominant during the wet season (May–June) [8].

Anopheles merus has long been known to breed in brackish water in the Eastern and Southern Coast of Africa and further inland [8, 37, 59, 62, 65, 66]. Larvae have been identified from breeding in a wide range of salinities(percent seawater): between 60 and 186% in Tanzania [8, 37, 67, 68], 46% in Jubaland [69], 60% in Swaziland [65], 18–205% in Mauritius [70,71,72], 30–96% in Kenya [64, 73] and 1.8–123% in South Africa [65, 74]. Larval survival in saline environments relies on regulation of haemolymph osmolarity through the intake absorption and excretion of ions in the rectum. Comparisons between fresh and saline water reared larvae showed that there was a dramatic shift in the rectal Na+/K+-ATPase protein localization [75]. It has also been shown that phenotypic tolerance of An. merus to saltwater is highly dependent on the timing of larval exposure to salinity, specifically within the first 24 h [76].

Various chemicals other than sodium chloride found in seawater have been thought to affect the development of An. merus. In Jimbo, Kenya, Mosha and colleagues [64] showed the importance of these salts (sodium chloride, potassium chloride, magnesium chloride, sodium sulphate, magnesium sulphate, sodium carbonate and potassium carbonate) in the survival of the larvae by comparing saltwater and seawater where the median lethal dose was 102.5% and 135.0% salinity respectively, suggesting that some chemicals in seawater might enable the tolerance of higher concentrations of sodium chloride. Earlier studies had also indicated that tolerance in some forms of An. maculipennis was improved by addition of minute amounts of calcium (in form of carbonates, chlorides or sulphates) [77]. For An. melas it was identified that magnesium sulphate was attractive to ovipositing females [78]. Toxicity tests also showed that sodium sulphate and magnesium sulphate were well tolerated and supported eclosion with less mortality than sodium chloride of the same concentration [64]. Recently, Jeanrenaud et al. showed that larval exposure to organic fertiliser led to an increase in the adult lifespan [79].

Habitats along the East and Southern African coast

There have been various accounts of An. merus along the Kenyan coast. In 1983, the species was identified in Jimbo village, Kwale district, both at the shoreline, which is made up of mangrove vegetation, and further inland in large semi-permanent brackish ponds [48]. In 2003, Mbogo and colleagues [29] reported the species in three coastal districts: Malindi, Kilifi and Kwale. In Kilifi, it was reported in Dindiri, Jaribuni and Majajani where the Jaribuni River and swamps along it turn saline during the dry season, in Malindi at Garithe, Manjenjeni, Masheheni and Mjanaheri while in Kwale at Amani, Gazi and Tsuini village. In Garithe village of Kilifi county, the species was identified in manmade pools, road drains, ponds swamps and hoofprints [59]. The localization of the species to the coastal region was suggested to be due to strict adaptation to saltwater breeding or competitive exclusion further inland by other members of the An. gambiae complex [58]. Wind-assisted dispersal of An. merus further inland was ruled out because of dense vegetation but with sparse vegetation, a mark and release experiment showed that the species can travel between 4.5 and 7 km [80].

In Changombe village in Dar-es-salaam, Tanzania, it was shown that the species breeding sites periodically occurred in swampy patches along the upper tidal limit that was only reached by the highest spring tides, around mangrove bushes and more than half a kilometre inland in shallow, brackish water ponds. The breeding season was usually in August, September and October [37]. The species was also identified in Kaole village where they concluded that An. merus at the coast survived longer than those further inland [81]. In Zanzibar, Pemba Island, the rugged coastline facilitates entry of seawater to the island during spring tides leaving saltwater pools that provide breeding sites for An. merus [8].

In Swaziland, the species has been found in pools about 90 km from the coastline and more than 121 km up the Usutu River containing about 63% saltwater [65]. Breeding sites in South Africa have been identified in saline pools at the edge of Inyamithe Pan, Northern Natal [65], and in cattle hoofprints formed along a hot mineral spring in Soutini [82].

In Madagascar, the species was first identified in a salt swamp near Toliara [83] later on at Mangatsa and Ankilifietra [51]. The species was always found ≥ 20 km from the coastline and in areas without mangroves showing that it was not dependent on them; there was no A. merus in Kimony, which is covered by a large mangrove forest [51].

In Mauritius, breeding sites were crab holes, former salt pans and further inland in large pools away from the shore. The sites were Baines des Dames, Drain Marie, Pointe aux Piments and L’Isle d’Ambre. The absence of larvae in the breeding sites was attributed to flooding during spring tides and drying up of the pools during low tide [72].

Conclusion

An. merus has been given little attention and very few studies have been done. The paucity of data on An. merus and its transmission dynamics needs to be bridged since the species is becoming an important vector of malaria and possibly lymphatic filariasis. It is also displaying both phenotypic and behavioural resistance to insecticides. This therefore calls for the deployment of innovative control strategies such as mass drug administration (endectocides such as ivermectin), larviciding, transgenic mosquitoes, zooprophylaxis, spatial repellents, attractive toxic sugar baits, “eave tubes” and targeting mosquito swarms.

Availability of data and materials

Data and analysis files are available in Harvard Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/1QOXQR.

Abbreviations

- KEMRI:

-

Kenya Medical Research Institute

- WHO:

-

World Health Organisation

- IRS:

-

Indoor Residual Spray

- DDT:

-

Dichloro-diphenyl-trichloroethane

- ITN:

-

Insecticide-treated bed nets

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses

References

WHO. World Malaria Report 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019.

Killeen GF, Fillinger U, Kiche I, Gouagna LC, Knols BGJ. Eradication of Anopheles gambiae from Brazil: lessons for malaria control in Africa? Lancet Infect Dis. 2002;2:618–27.

Nájera JA. Malaria control: achievements, problems and strategies. Parassitologia. 2001;43:1–89.

Rieckmann KH. The chequered history of malaria control: are new and better tools the ultimate answer? Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2006;100:647–62.

WHO. Eighth World Health Assembly. World Health Organization. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1955.

WHO. Re-examination of the Global Strategy of malaria eradication. World Heal Organ 1969;

East African Institute Of Malaria And Vector-Borne Diseases. Report on the Pare-Taveta Malaria Scheme, 1954–1959. East Africa High Commission, 1960.

Iyengar R. The bionomics of salt-water Anopheles gambiae in East Africa. Bull World Health Organ. 1962;27:223–9.

Pringle G. Malaria in the pare area of Tanzania III The course of malaria transmission since the suspension of an experimental programme of residual insecticide spraying. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1967;61:69–79.

Loeb F, Clark WM, Coatney GR, et al. Activity of a new antimalarial agent, chloroquine (SN 7618). J Am Med Assoc. 1946;130:1069–70.

Payne D. Spread of chloroquine resistance in Plasmodium falciparum. Parasitol Today. 1987;3:241–6.

Yamey G. African heads of state promise action against malaria. BMJ. 2000;320:1228.

Abdel-Hameed Adeel AA, Charlwood JD. Roll Back Malaria: a failing global health challenge. Br Med J. 2004;328:1378.

Maharaj R, Kissoon S, Lakan V, Kheswa N. Rolling back malaria in Africa—challenges and opportunities to winning the elimination battle. South African Med J. 2019;109:53–6.

WHO. World Malaria Report 2017. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017.

Nájera JA, González-Silva M, Alonso PL. Some lessons for the future from the global malaria eradication programme (1955–1969). PLoS Med 2011; 8.

WHO. Global technical strategy for malaria 2016–2030. World Health Organization 2015. p. 1–35.

Russell TL, Govella NJ, Azizi S, Drakeley CJ, Kachur SP, Killeen GF. Increased proportions of outdoor feeding among residual malaria vector populations following increased use of insecticide-treated nets in rural Tanzania. Malar J. 2011;10:1–10.

Sherrard-Smith E, Skarp JE, Beale AD, et al. Mosquito feeding behavior and how it influences residual malaria transmission across Africa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2019;116:15086–96.

Derua YA, Alifrangis M, Hosea KM, et al. Change in composition of the Anopheles gambiae complex and its possible implications for the transmission of malaria and lymphatic filariasis in north-eastern Tanzania. Malar J. 2012;11:1–9.

Bamou R, Mbakop LR, Kopya E, et al. Changes in malaria vector bionomics and transmission patterns in the equatorial forest region of Cameroon between 2000 and 2017. Parasites Vectors. 2018;11:1–13.

Mwangangi JM, Midega JT, Keating J, et al. Shifts in malaria vector species composition and transmission dynamics along the Kenyan coast over the past 20 years. Malar J. 2013;12:1–9.

WHO. Global report on insecticide resistance in malaria vectors: 2010–2016. Geneva: 2018.

Hargreaves K, Hunt RH, Brooke BD, et al. Anopheles arabiensis and An. quadriannulatus resistance to DDT in South Africa. Med Vet Entomol. 2003;17:417–22.

Ranson H, N’Guessan R, Lines J, Moiroux N, Nkuni Z, Corbel V. Pyrethroid resistance in African anopheline mosquitoes: what are the implications for malaria control? Trends Parasitol. 2011;27:91–8.

Protopopoff N, Matowo J, Malima R, et al. High level of resistance in the mosquito Anopheles gambiae to pyrethroid insecticides and reduced susceptibility to bendiocarb in north-western Tanzania. Malar J. 2013;12:1–8.

Fernandes JN, Moise IK, Maranto GL, Beier JC. Revamping mosquito-borne disease control to tackle future threats. Trends Parasitol. 2018;34:359–68.

Kipyab PC, Khaemba BM, Mwangangi JM, Mbogo CM. The bionomics of Anopheles merus (Diptera: Culicidae) along the Kenyan coast. Parasites Vectors. 2013;6:2–7.

Mbogo CM, Mwangangi JM, Nzovu JG, et al. Spatial and temporal heterogeneity of Anopheles mosquitoes and Plasmodium falciparum transmission along the Kenyan coast. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2003;68:734–42.

The Polar Geospatial Center. PGC Coordinate Converter. https://www.pgc.umn.edu/apps/convert/.

R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. 2018.

Kruskal WH, Wallis WA. Use of ranks in one-criterion variance analysis. J Am Stat Assoc. 1952;47:583–621.

Pielou EC. An introduction to mathematical ecology. New York: USA, Wiley-Inter-science; 1969.

Margalef R. Information theory in ecology Gen Syst. 1958;3:36–71.

Shannon CE. A mathematical theory of communication. Bell Syst Tech J. 1948;27:623–56.

Simpson EH. Measurement of diversity. Nature. 1949;163:688.

Muirhead Thomson RC. Studies on salt-water and fresh-water Anopheles gambiae on the East African Coast. Bull Entomol Res. 1951;41:487–502.

Coluzzi M. Morphological divergences in the Anopheles Gambiae complex. Riv Malariol. 1964;43:197–232.

Hunt RH. A cytological technique for the study of Anopheles gambiae complex. Parassitologia. 1973;15:137–9.

Mahon RJ, Green CA, Hunt RH. Diagnostic allozymes for routine identification of adults of the Anopheles gambiae complex (Diptera, Culicidae). Bull Entomol Res. 1976;66:25–31.

Collins FH, Mendez MA, Rasmussen MO, Mehaffey PC, Besansky NJ, Finnerty V. A ribosomal RNA gene probe differentiates member species of the Anopheles gambiae complex. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1987;37:37–41.

Collins FH, Petrarca V, Mpofu S, et al. Comparison of DNA probe and cytogenetic methods for identifying field collected Anopheles gambiae complex mosquitoes. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1988;39:545–50.

Hill SM, Urwin R, Knapp TF, Crampton JM. Synthetic DNA probes for the identification of sibling species in the Anopheles gambiae complex. Med Vet Entomol. 1991;5:455–63.

Scott JA, Brogdon WG, Collins FH. Identification of single specimens of the Anopheles gambiae complex by the polymerase chain reaction. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1993;49:520–9.

Müller P, Pflüger V, Wittwer M, et al. Identification of cryptic anopheles mosquito species by molecular protein profiling. PLoS One. 2013;8:e57486.

Mayagaya VS, Michel K, Benedict MQ, et al. Non-destructive determination of age and species of Anopheles gambiae s.l. using near-infrared spectroscopy. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009;81:622–30.

Bonizzoni M, Afrane Y, Yan G. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) for rapid identification of Anopheles gambiae and Anopheles arabiensis mosquitoes. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009;81:1030–4.

Mutero CM, Mosha FW, Subra R. Biting activity and resting behaviour of Anopheles merus Donitz (Diptera: Culicidae) on the Kenya coast. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1984;78:43–7.

Sharp BL. Anopheles merus (Donitz) its biting cycle in relation to environmental parameters. J Entomol Soc South Afr. 1983;46:367–74.

Cuamba N, Mendis C. The role of Anopheles merus in malaria transmission in an area of southern Mozambique. J Vector Borne Dis. 2009;46:157–9.

Tsy JM, Duchemin J-B, Marrama L, et al. Distribution of the species of the Anopheles gambiae complex and first evidence of Anopheles merus as a malaria vector in Madagascar. Malar J. 2003;2:33. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2875-2-33.

Mbokazi F, Coetzee M, Brooke B, et al. Changing distribution and abundance of the malaria vector Anopheles merus in Mpumalanga Province, South Africa. Public Heal Action. 2018;8:S39–43.

Govere J, Durrheim DN, Coetzee M, Hunt RH, La Grange JJ. Captures of mosquitoes of the Anopheles gambaie complex (Diptera: Culicidae) in Lowveld Region of Mpumalanga Province, South Africa. African Entomol. 2000;8:91–9.

Davies C, Coetzee M, Lyons CL. Characteristics of larval breeding sites and insecticide resistance in the Anopheles gambiae complex in Mpumalanga, South Africa. African Entomol. 2016;24:421–31.

WHO. Global programme to eliminate lymphatic flariasis: progress report, 2014. Geneva: 2014.

WHO (World Health Organization). Lymphatic filariasis. 2020. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/lymphatic-filariasis. Accessed 15 June 2020.

Bushrod FM. The Anopheles gambiae giles complex and bancroftian filariasis transmission in a tanzanian coastal village. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1981;75:93–100.

Mosha FW, Petrarca V. Ecological studies on Anopheles gambiae complex sibling species on the Kenya coast. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1983;77:344–5.

Kipyab PC, Khaemba BM, Mwangangi JM, Mbogo CM. The physicochemical and environmental factors affecting the distribution of Anopheles merus along the Kenyan coast. Parasites Vectors. 2015;8:1–8.

Sunahara T, Ishizaka K, Mogi M. Habitat size: a factor determining the opportunity for encounters between mosquito larvae and aquatic predators. J Vector Ecol. 2002;27:8–20.

Service MW. Mortalities of the immature stages of species b of the Anopheles gambiae complex in Kenya: comparison between rice fields and temporary pools, identification of predators, and effects of insecticidal spraying. J Med Entomol. 1977;13:535–45.

Mwangangi JM, Mbogo CM, Muturi EJ, et al. Spatial distribution and habitat characterisation of Anopheles larvae along the Kenyan coast. J Vector Borne Dis. 2007;44:44–51.

Gimnig JE, Ombok M, Otieno S, Kaufman MG, Vulule JM, Walker ED. Density-dependent development of Anopheles gambiae (Diptera: Culicidae) larvae in artificial habitats. J Med Entomol. 2002;39:162–72.

Mosha FW, Mutero CM. The influence of salinity on larval development and population dynamics of Anopheles merus Dönitz (Diptera: Culicidae). Bull Entomol Res. 1982;72:119–28.

Paterson HE, Patorson JS. Records of the breeding of ‘Saltwater Anopheles gambiae’ at the inland localities in Southern Africa. Nature. 1964;201:524–5.

Paterson HE. Status of the east african salt-water-breeding variant of Anopheles gambiae Giles. Nature. 1962;195:469–70.

Mackay R. Second (Final) Report of the Malaria Unit, Dar es Salaam, for the Period November 1934 to December 1936. 1938; pp. 61.

Kuhlow F. Studies on the bionomics and the morphology of the saltwater breeding Anopheles gambiae on the coast of Tanganyika. Riv Malariol. 1962;41:187–97.

Maffi M. Focolaio larvale di A. gambiae e di A. squamosus in raccolta d’acqua salata, a Busc Busc (fascia costiera del basso Oltre Giuba). Riv Malar. 1960;39:131–3.

Jepson WF, Moutia A, Courtois C. The malaria problem in Mauritius: the bionomics of Mauritian anophelines. Bull Entomol Res. 1947;38:177–208.

Halcrow JG. A new Sub-species of Anopheles gambiae giles from Mauritius. East Afr Med J. 1957;34:133–5.

Paterson HE. Report on studies on the Anopheles gambiae complex on Mauritius. WHO 1963.

Kipyab PC. The physicochemical and environmental factors affecting the distribution of Anopheles merus along the Kenyan coast. Parasites Vectors. 2015;8:221.

Coetzee M, Hunt RH, Braack LEO, Davidson G. Distribution of mosquitoes belonging to the Anopheles gambiae complex, including malaria vectors, south of latitude 15°S. S Afr J Sci. 1993;89:227–31.

Smith KE, VanEkeris LA, Okech BA, Harvey WR, Linser PJ. Larval anopheline mosquito recta exhibit a dramatic change in localization patterns of ion transport proteins in response to shifting salinity: a comparison between anopheline and culicine larvae. J Exp Biol. 2008;211:3067–76.

White BJ, Kundert PN, Turissini DA, Van Ekeris L, Linser PJ, Besansky NJ. Dose and developmental responses of Anopheles merus larvae to salinity. J Exp Biol. 2013;216:3433–41.

Bates M. The use of salt solutions for the demonstration of physiological differences between the larvae of certain European Anopheline mosquitoes. Am J Trop Med. 1939;19:357–84.

Giglioli MEC. Tides, salinity and the breeding of Anopheles mêlas (Theobald, 1903) during the dry season in the Gambia. Riv Malariol. 1964;43:245–63.

Jeanrenaud ACSN, Brooke BD, Oliver SV. The effects of larval organic fertiliser exposure on the larval development, adult longevity and insecticide tolerance of zoophilic members of the Anopheles gambiae complex (Diptera: Culicidae). PLoS ONE. 2019;14(4):e0215552.

Gillies MT, De Meillon B. The Anophelinae of Africa south of the Sahara (Ethiopian zoogeographical region). Anophelinae Africa south Sahara (Ethiopian Zoogeographical Reg 1968;

Temu EA, Minjas JN, Coetzee M, Hunt RH, Shiff CJ. The role of four anopheline species (Diptera: Culicidae) in malaria transmission in coastal Tanzania. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1998;92:152–8.

Coetzee M, Cross H. Mating experiments with two populations of Anopheles merus Donitz (Diptera: Culicidae). J Entomol Soc South Afr 1983; 46:257–259. http://content.ajarchive.org/cgi-bin/showfile.exe?CISOROOT=/0012-8789&CISOPTR=199%5Cn. http://hdl.handle.net/10499/AJ9935.

G. Chauvet. Répartition et écologie du complexe à Madagascar * Anopbeles gnnhae. 1969; VII.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The work is supported by The Royal Society FLAIR fellowship grant FLR_R1_190497 (awarded to MKR) and WHO-TDR 2016/602099-0 (awarded to MKR and JM). The funding bodies did not have any role in the design, data collection, data analysis and interpretation and writing of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BB conducted the literature review and drafted the manuscript. MKR and JM contributed to the design of the study and selection of the articles. IO, CM, JM and MKR contributed substantially to data interpretation and revising the draft manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

This paper is published with the permission of the Director General of the Kenya Medical Research Institute.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

13071_2021_4582_MOESM1_ESM.docx

Additional file 1. Mosquito collection sites, coordinates, date of collection, mosquito counts, indoor or outdoor collection, mosquito stage and the relevant references.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Bartilol, B., Omedo, I., Mbogo, C. et al. Bionomics and ecology of Anopheles merus along the East and Southern Africa coast. Parasites Vectors 14, 84 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-021-04582-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-021-04582-z