Abstract

Background

The life-cycle of many vector-borne pathogens includes an asexual replication phase in the vertebrate host and sexual reproduction in the insect vector. However, as only a small array of parasites can successfully develop infective phases inside an insect, few insect species are competent vectors for these pathogens. Molecular approaches have identified the potential insect vectors of blood parasites under natural conditions. However, the effectiveness of this methodology for verifying mosquito competence in the transmission of avian malaria parasites and related haemosporidians is still under debate. This is mainly because positive amplifications of parasite DNA in mosquitoes can be obtained not only from sporozoites, the infective phase of the malaria parasites that migrate to salivary glands, but also from different non-infective parasite forms in the body of the vector. Here, we assessed the vectorial capacity of the common mosquito Culex pipiens in the transmission of two parasite genera.

Methods

A total of 1,560 mosquitoes were allowed to feed on five house sparrows Passer domesticus naturally infected by Haemoproteus or co-infected by Haemoproteus/Plasmodium. A saliva sample of the mosquitoes that survived after 13 days post-exposure was taken to determine the presence of parasite DNA by PCR.

Results

Overall, 31.2% mosquito’s head-thorax and 5.8% saliva samples analysed showed positive amplifications for avian malaria parasites. In contrast to Haemoproteus DNA, which was not found in either the body parts or the saliva, Plasmodium DNA was detected in both the head-thorax and the saliva of mosquitoes. Parasites isolated from mosquitoes feeding on the same bird corresponded to the same Plasmodium lineage.

Conclusions

Our experiment provides good evidence for the competence of Cx. pipiens in the transmission of Plasmodium but not of Haemoproteus. Molecular analyses of saliva are an effective method for testing the vector competence of mosquitoes and other insects in the transmission of vector-borne pathogens.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

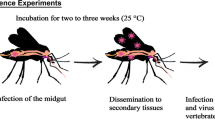

The avian malaria parasite Plasmodium and the malaria-like parasites of the genus Haemoproteus are pathogens that infect birds worldwide and cause infectious diseases that affect birds’ fitness [1, 2]. These parasites reproduce asexually in birds but are obliged to complete their sexual and sporogonic phases in their insect vectors before being successfully transmitted to a new vertebrate host. Mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae), especially those of the genus Culex, are the main vectors of avian Plasmodium; biting midges Culicoides (Diptera: Ceratopogonidae) and louse flies (Diptera: Hippoboscidae), on the other hand, transmit Haemoproteus (subgenera Parahaemoproteus and Haemoproteus) parasites, respectively [3, 4]. In mosquitoes, after the development of the ookinetes, parasites penetrate insects’ mid-gut walls and produce oocysts. These oocysts then divide to produce the sporozoites, the infective form of the malaria parasites, which migrate to the salivary glands of the mosquitoes. Sporozoites are thus transmitted by mosquito bites into the bloodstream of a new host [4].

Since the seminal paper by Bensch et al. [5], a number of different molecular approaches have been developed to study interactions between parasites and birds [6, 7]. These molecular methods are also a valuable tool for identifying the potential insect vectors of blood parasites under natural conditions [8, 9]. However, an intense debate exists regarding the reliability of molecular approaches in the study of vector competence [10, 11]. This controversy arises from the fact that positive amplification of parasite DNA can be obtained from insects due to the presence of non-infective forms of the parasite, which are unable to complete their multiplicative cycle. For instance, Haemoproteus DNA has been isolated from both Culicoides [12, 13] and several mosquito species, including Culex pipiens, which have completely digested blood meals [14–17]. All this evidence suggests that mosquitoes (and not only Culicoides) could be involved in the transmission of this parasite genus. Therefore, further studies are still required to determine the degree to which mosquitoes are competent in the transmission of Haemoproteus parasites.

We conducted an experimental study to determine, to our knowledge for the first time, the competence of Cx. pipiens mosquitoes in the transmission of avian malaria-like parasites of the genus Haemoproteus. Culex pipiens is a widely distributed mosquito species involved in the transmission of a number of vector-borne pathogens [18]. It is believed to be one of the main vectors of avian malaria parasites, and over 50 different genetic lineages have been detected in this mosquito species using molecular methods [14, 19]. To assess vector competence, mosquitoes were allowed to feed on wild birds naturally infected by Haemoproteus and birds co-infected by Haemoproteus and Plasmodium (individuals suffering co-infections are commonly found in the wild) [20–22]. After allowing the parasite to develop in the mosquito, we used molecular tools (PCR) to detect the presence of parasite DNA in the head-thorax (where the salivary glands are located) and saliva of mosquitoes. The detection of pathogens in mosquito saliva is frequently used in studies of the vector competence of pathogens such as West Nile virus [23] and Chikungunya virus [24] but, to the best of our knowledge, has never previously been employed to determine the vector competence of mosquitoes for avian malaria and malaria-like parasites.

Methods

Mosquito collection and rearing

Culex pipiens larvae were collected in La Cañada de los Pájaros, a natural reserve near Seville, Spain (6°14′W, 36°57′N). This area lies beyond the main wetlands of the Doñana National Park and consists of a freshwater lake (c.5 ha) surrounded by paddy fields. Larvae were transferred to the laboratory and kept in plastic trays with fresh water and fed ad libitum (Mikrozell 20 ml/22 g; Dohse Aquaristik GmbH & Co. KG, D-53501, Gelsdorf, Germany). Larvae and adult mosquitoes were maintained at constant conditions, 28 °C, 65–70% relative humidity (RH) and 12:12 light: dark cycle. After metamorphosis, adult mosquitoes were immediately placed in insect cages (BugDorm-43030F, 32.5 × 32.5 × 32.5 cm) and fed ad libitum with 1% sugar solution. Five to seven days later, adults were anesthetised with ether [25] and observed under a stereomicroscope (Nikon SMZ645) to determine their sex and confirm the species, following Schaffner et al. [26] and Becker et al. [27]. The sugar solution was replaced with water 24 h prior to each experiment (see below) and completely removed from cages 12 h before experiments began. The experiments were conducted using 13–22-day-old female Cx. pipiens.

Bird trapping and sampling

Five juvenile (yearlings) house sparrows Passer domesticus were captured using mist nets on 15 July 2014 in Huelva province and subsequently ringed with numbered metal rings. To determine their haemosporidian infection status, a blood sample (0.2 ml) was taken from the jugular vein of each bird using sterile syringes and was then immediately transferred to non-heparinized Eppendorf tubes. Birds were transported to the Unit of Animal Experimentation at the Estación Biológica de Doñana (EBD-CSIC) and kept indoors in birdcages (58.5 × 25 × 36 cm) in a vector-free room under controlled conditions (23 ± 1 °C, 40–50% RH and 12:12 light: dark cycle). Birds were fed ad libitum with a standard mixed diet for seed-eating and insectivorous birds (KIKI; GZM S.L., Alicante, Spain). Three days after the last exposure to mosquitoes, birds were blood sampled again (0.2 ml; final blood samples) in the same way as above to detect any infections by blood parasites that could have not developed when initially sampled. Samples were not taken either immediately before or during the mosquito exposure period due to the stress caused by mosquito bites. Immediately after sampling, a drop of blood was smeared, air-dried, fixed in absolute methanol and stained with Giemsa for 45 min [28]. A total of 4,000–10,000 erythrocytes from each blood smear were scanned at high magnification (×1000) and the intensity of infection by Haemoproteus/Plasmodium parasites was estimated as the percentage of parasite cells per 100 erythrocytes. At the end of the experiment, birds were released at the capture site 23 days after being captured.

Experimental procedure

Eleven days after capture, each bird was placed in a birdcage (38.5 × 25.5 × 26 cm) inside an insect tent (BugDorm-2120, 60 × 60 × 60 cm). Over four non-consecutive nights, each bird was introduced into an independent tent and exposed to 50 (first night), 57 (second night), 105 (third night) and 100 (fourth night) unfed Cx. pipiens females, summarizing a total of 312 mosquitoes per bird. The number of mosquitoes used each night varied according to the availability of unfed 13–22 days old mosquitoes. Birds were exposed to mosquito bites overnight (from 8:00 pm to 8:00 am). After exposure, mosquitoes with a recent blood meal in the abdomen were immediately separated and placed in unzipped insect cages (BugDorm-43030F 32.5 × 32.5 × 32.5 cm) and maintained under standard conditions (28 °C, 65–70% RH and 12:12 light: dark cycle). These mosquitoes had ad libitum access to 1% sugar solution during the following 13 days to allow parasite development.

Sampling of mosquito saliva

Those mosquitoes that survived until 13 days post-exposure (dpe) were anesthetised with ether [25]. Mosquitoes’ legs and wings were removed with a sterile forceps. The mosquito proboscis was introduced into a 1 μl disposable capillary (Einmal-Kapillarpipetten, Hirschmann® Laborgeäte, Germany) filled with 1 μl of fetal bovine serum [29]. Then, 1 μl of 2% pilocarpine (Novartis 2012, Alcon Cusí S.A. Barcelona, Spain) was applied to the mosquito thorax to stimulate salivation [30]. After 45 min, the medium containing the saliva was placed in 1.5 ml Eppendorf tubes with 10 μl of MQ water and stored at −80 °C. Mosquitoes were kept in individual tubes at -80 °C until further molecular analysis. The head-thorax of eight mosquitoes and two saliva samples were not analysed due to logistical problems.

Molecular detection and identification of blood parasites

DNA was isolated from birds’ blood samples (both the initial and final samples) and from the head-thorax of mosquitoes using a semi-automatic procedure (MAXWELL® 16 LEV Blood DNA Kit) [31]. The Qiagen DNeasy® Kit Tissue and Blood (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) was used to isolate the DNA from saliva samples. A 478 bp fragment (excluding primers) of the mitochondrial cytochrome b gene of Haemoproteus/Plasmodium parasites was amplified following Hellgren et al. [6]. This procedure is based on a first PCR using primers HaemNFI (5′-CAT ATA TTA AGA GAA ITA TGG AG-3′) and HaemNR3 (5′-ATA GAA AGA TAA GAA ATA CCA TTC-3′), followed by a nested PCR using primers HaemF (5′-ATG GTG CTT TCG ATA TAT GCA TG-3′) and HaemR2 (5′-GCA TTA TCT GGA TGT GAT AAT GGT-3′). This procedure is able to detect parasite DNA in infections equivalent to less than one gametocyte per 10,000 erythrocytes in blood smears [6]. The presence of amplicons was verified in 1.8% agarose gels. Positive amplifications were sequenced in both directions using the BigDye technology (Applied Biosystems) or with the Macrogen sequencing service (Macrogen Inc., Amsterdam, The Netherlands). Sequences were edited using the software Sequencher™ v 4.9 (Gene Codes Corp. © 1991–2009, Ann Arbor, MI 48108, USA) and assigned to parasite lineages/morphospecies after comparison with the GenBank (National Center for Biotechnology Information) and Malavi [19] databases.

Results

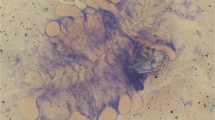

The five birds included in the study showed positive amplifications of blood parasites and there was no difference between initial and final samples. The parasite sequences isolated from all five birds had a 100% overlap with lineage Haemoproteus PADOM05 (corresponding to H. passeris). No evidence of double peaks in the chromatograms was found. The examination of blood smears revealed the presence of both Haemoproteus and Plasmodium parasites in two birds (house sparrows 4 and 5), only Haemoproteus in two other birds (house sparrows 2 and 3), and a total absence of parasites in one bird (house sparrow 1) (Fig. 1, Table 1).

Overall, 174 of 1560 (11.2%) mosquitoes used in this study fed on birds’ blood, 149 of them survived until 13 dpe. A total of 141 head-thorax and 139 saliva samples were molecularly analysed, of which 44 and 8 samples, respectively, were positive to parasite DNA (Table 1). All the saliva samples showing positive amplifications corresponded to mosquitoes with head-thorax that were also positive for parasite DNA. The parasite lineages isolated from the head-thorax and saliva of the mosquitoes that fed on the two co-infected birds, as revealed by the blood smears, corresponded to Plasmodium lineages. These lineages were identified as SGS1 (= Rinshi-1, corresponding to Plasmodium relictum) and PADOM01. We were unable to detect Plasmodium in the blood smear of one bird (identified as house sparrow 3, Table 1), probably due to a very low-intensity of infection, but did manage to isolate the P. relictum lineage GRW11 (= Rinshi-7) in the head-thorax of one of the 36 mosquitoes that fed on this bird (Table 1). Parasites isolated from mosquitoes feeding on the same individual corresponded to the same Plasmodium lineage. Haemoproteus was not found in either the head-thorax or in the saliva of any of the mosquitoes analysed.

Discussion

Studies of host-parasite co-evolution in the context of avian malaria mainly focus on the interactions between parasites and their vertebrate hosts [32–34] but tend to ignore the role of invertebrate vectors. The development of avian blood parasites in mosquitoes is the outcome of a complex evolutionary ‘arms race’ too, in which the probability of encounter with mosquitoes and their compatibility are important obstacles for successful infection and the proper development of the parasites [35, 36]. Although Cx. pipiens females frequently feed on mammals, birds are their main blood-feeding source [18, 37, 38], a preference that may increase their contact rate with Haemoproteus. Nevertheless, our results suggest that mosquitoes actually may represent an obstacle to the successful development of the life-cycle of species in this parasite genus [36].

Here, we provide evidence of the effectiveness of mosquito saliva as a novel way of testing the vectorial competence of mosquitoes in the transmission of avian malaria and malaria-like parasites. This method has been commonly used in studies of the vector competence of mosquitoes in the transmission of a number of viruses that are of public health concern [39–42] as well as to detect proteins of Plasmodium bergehi sporozoites in the saliva of Anopheles stephensi [43]. However, to our knowledge, this approach has never been used in studies of mosquito-avian malaria interactions. Despite being time-consuming (it is possible to obtain the saliva of about 15 mosquitoes/h), this method is an excellent complementary procedure to the frequently used salivary gland dissection employed in studies on vector competence. By using this approach, it is possible to obtain parasite sporozoites while reducing/removing the presence of tissues derived from the salivary glands present in the sample. This could be of special relevance in studies on Plasmodium genotyping where the quantity of parasite DNA in relation to host DNA is an important limitation [44]. Moreover, mosquito saliva could be used in transcriptomic studies of the infective forms of avian malaria parasites and/or to study the parasite load inoculated by mosquitoes [45].

The lineages SGS1 (P. relictum) and PADOM01 were amplified in the saliva of mosquitoes at 13 dpe. However, a high percentage of mosquitoes with positive DNA amplifications in the head-thorax (81.8%) did not show positive Plasmodium DNA amplifications in saliva at 13 dpe. A recent study found that 13.3% of infected Cx. pipiens had Plasmodium sporozoites in their salivary glands [46], indicating that these parasites develop sporozoites in only a small percentage of infected mosquitoes. The absence of sporozoites in salivary glands could be explained by the fact that the parasite does not have enough time to complete its development until this phase. Thus, extracting saliva after 13 dpe could have increased the number of positive amplifications in our samples. However, some studies have found Plasmodium sporozoites in the salivary glands of mosquitoes from just 7 dpe [4, 47], although Kazlauskienė et al. [48] were unable to isolate sporozoites until 14 dpe in salivary glands (yet mosquitoes at 13 dpe were not analysed). The differences found between studies could be due to the use of different mosquito species, a differential mosquito microbiota, parasite strains, or environmental temperatures, which may greatly affect the ability of parasites to complete sporogony [4, 49, 50]. Unlike Plasmodium, the possibility that Haemoproteus had not have enough time to develop sporozoites is poorly supported. Previous studies using direct observational (microscope) and molecular (PCR) techniques found intermediate stages (i.e. ookinetes and oocysts) of Haemoproteus parasites in the head, thorax and/or abdomen of Ochlerotatus cantans mosquitoes from 4–6 dpe onwards, but presence of sporozoites was not recorded [51, 52]. By contrast, we found no evidence of Haemoproteus DNA in the head-thorax of the mosquitoes analysed. In addition, in their known Culicoides vectors, Haemoproteus sporozoites are also present in salivary glands at 5 dpe [53]. Therefore, our results support the inability of Haemoproteus lineage PADOM05 to complete its life-cycle in Cx. pipiens.

Molecular approaches allowing the identification of the parasite lineages harboured by insect vectors provide valuable information on the potential transmission networks of avian pathogens [12, 14, 16, 17]. Such tools enable a huge number of individuals (e.g. thousands of mosquitoes) to be handled, which is often necessary for detecting positive amplifications due to the low infection prevalence that is typical in mosquitoes trapped in the wild [15, 54, 55]. However, results from these studies should be interpreted with caution when attempting to identify the true vectors of avian pathogens, this is especially true when pathogen DNA is isolated from an unexpected vector, and highlights the necessity to conduct further experimental studies of vectorial competence [10]. Although different approaches including cloning and the development of specific primers have been employed to identify parasite lineages in co-infected birds [7, 56, 57], our results show the importance of combining the molecular detection of blood parasites with the analysis of blood smears when aimed at identifying potential co-infections in birds [58].

Conclusions

The results from this study suggest that Cx. pipiens is unable to transmit Haemoproteus parasites. This study also highlights the value of targeting mosquito saliva as a means of assessing the competence of potential mosquito vectors in the transmission of avian Plasmodium lineages.

Abbreviations

- dpe:

-

Days post-exposure

References

Merino S, Moreno J, Sanz JJ, Arriero E. Are avian blood parasites pathogenic in the wild? A medication experiment in blue tits (Parus caeruleus). Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2000;267(1461):2507–10.

Marzal A, De Lope F, Navarro C, Møller AP. Malarial parasites decrease reproductive success: an experimental study in a passerine bird. Oecologia. 2005;142(4):541–5.

Atkinson CT, Van Riper C. Pathogenicity and epizootiology of avian haematozoa: Plasmodium, Leucocytozoon and Haemoproteus. In: Loye JE, Zuk M, editors. Bird-parasite interactions: ecology, evolution, and behavior. London: Oxford University Press; 1991. p. 19–48.

Valkiūnas G. Avian malaria parasites and other haemosporidia. Boca Ratón: CRC press; 2005.

Bensch S, Stjernman M, Hasselquist D, Örjan Ö, Hannson B, Westerdahl H, Pinheiro RT. Host specificity in avian blood parasites: a study of Plasmodium and Haemoproteus mitochondrial DNA amplified from birds. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2000;267(1452):1583–9.

Hellgren O, Waldenström J, Bensch S. A new PCR assay for simultaneous studies of Leucocytozoon, Plasmodium, and Haemoproteus from avian blood. J Parasitol. 2004;90(4):797–802.

Martínez J, Martínez-de la Puente J, Herrero J, del Cerro S, Lobato E, Rivero-de Aguilar J, et al. A restriction site to differentiate Plasmodium and Haemoproteus infections in birds: on the inefficiency of general primers for detection of mixed infections. Parasitology. 2009;136(07):713–22.

Ishtiaq F, Guillaumot L, Clegg SM, Phillimore AB, Black RA, Owens IP, et al. Avian haematozoan parasites and their associations with mosquitoes across Southwest Pacific Islands. Mol Ecol. 2008;17(20):4545–55.

Levin II, Valkiūnas G, Iezhova TA, O’Brien SL, Parker PG. Novel Haemoproteus species (Haemosporida: Haemoproteidae) from the swallow-tailed gull (Lariidae), with remarks on the host range of hippoboscid-transmitted avian hemoproteids. J Parasitol. 2012;98(4):847–54.

Valkiūnas G. Haemosporidian vector research: marriage of molecular and microscopical approaches is essential. Mol Ecol. 2011;20(15):3084–6.

Seblova V, Sadlova J, Carpenter S, Volf P. Speculations on biting midges and other bloodsucking arthropods as alternative vectors of Leishmania. Parasite Vector. 2014;7(1):222.

Martínez-de la Puente J, Martínez J, Aguilar RD, Herrero J, Merino S. On the specificity of avian blood parasites: revealing specific and generalist relationships between haemosporidians and biting midges. Mol Ecol. 2011;20(15):3275–87.

Ferraguti M, Martínez-de la Puente J, Ruiz S, Soriguer R, Figuerola J. On the study of the transmission networks of blood parasites from SW Spain: diversity of avian Haemosporidians in the biting midge Culicoides circumscriptus and wild birds. Parasite Vector. 2013;6(1):208.

Santiago-Alarcón D, Palinauskas V, Schaefer HM. Diptera vectors of avian haemosporidian parasites: untangling parasite life cycles and their taxonomy. Biol Rev. 2012;87(4):928–64.

Ferraguti M, Martínez-de la Puente J, Muñoz J, Roiz D, Ruiz S, Soriguer R, Figuerola J. Avian Plasmodium in Culex and Ochlerotatus mosquitoes from southern Spain: effects of season and host-feeding source on parasite dynamics. PLoS One. 2013;8(6):e66237.

Synek P, Munclinger P, Albrecht T, Votýpka J. Avian haemosporidians in haematophagous insects in the Czech Republic. Parasitol Res. 2013;112(2):839–45.

Zélé F, Vézilier J, L’Ambert G, Nicot A, Gandon S, Rivero A, Duron O. Dynamics of prevalence and diversity of avian malaria infections in wild Culex pipiens mosquitoes: the effects of Wolbachia, filarial nematodes and insecticide resistance. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7(1):1–16.

Farajollahi A, Fonseca DM, Kramer LD, Kilpatrick AM. “Bird biting” mosquitoes and human disease: a review of the role of Culex pipiens complex mosquitoes in epidemiology. Infect Genet Evol. 2011;11(7):1577–85.

Bensch S, Hellgren O, Pérez-Tris J. MalAvi: a public database of malaria parasites and related haemosporidians in avian hosts based on mitochondrial cytochrome b lineages. Mol Ecol Resour. 2009;9(5):1353–8.

Marzal A, Bensch S, Reviriego M, Balbontin J, De Lope F. Effects of malaria double infection in birds: one plus one is not two. J Evol Biol. 2008;21(4):979–87.

Merino S, Moreno J, Vásquez RA, Martínez J, Sánchez-Monsálvez I, Estades CF, et al. Haematozoa in forest birds from southern Chile: latitudinal gradients in prevalence and parasite lineage richness. Austral Ecol. 2008;33(3):29–40.

del Cerro S, Merino S, Martínez-de la Puente J, Lobato E, Ruiz-de-Castañeda R, Rivero-de Aguilar J, et al. Carotenoid-based plumage colouration is associated with blood parasite richness and stress protein levels in blue tits (Cyanistes caeruleus). Oecologia. 2010;162(4):825–35.

Goddard LB, Roth AE, Reisen WK, Scott TW. Vector competence of California mosquitoes for West Nile virus. Emerg Infect Dis. 2002;8(12):1385–91.

Dubrulle M, Mousson L, Moutailler S, Vazeille M, Failloux AB. Chikungunya virus and Aedes mosquitoes: saliva is infectious as soon as two days after oral infection. PLoS One. 2009;4(6):e5895.

Lipnick R. Narcosis induced by ether and chloroform. In: Studies of Narcosis. Netherlands: Springer; 1991. p. 93–107.

Schaffner E, Angel G, Geoffroy B, Hervy JP, Rhaiem A, Brunhes J. The mosquitoes of Europe: an identification and training programme. Montpellier: IRD Editions; 2001.

Becker N, Petric D, Zgomba M, Boase C, Madon M, Dahl C, Kaiser A. Mosquitoes and their control. 2nd ed. New York: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2010.

Gering E, Atkinson CT. A rapid method for counting nucleated erythrocytes on stained blood smears by digital image analysis. J Parasitol. 2004;90(4):879–81.

Phillips A, Mossel E, Sanchez-Vargas I, Foy B, Olson K. Alphavirus transducing system: tools for visualizing infection in mosquito vectors. J Vis Exp. 2010;45:e2363.

Boorman J. Induction of salivation in biting midges and mosquitoes, and demonstration of virus in the saliva of infected insects. Med Vet Entomol. 1987;1(2):211–4.

Gutiérrez-López R, Martínez-de la Puente J, Gangoso L, Soriguer R, Figuerola J. Comparison of manual and semi-automatic DNA extraction protocols for the barcoding characterization of haematophagous louse flies (Diptera: Hippoboscidae). J Vector Ecol. 2015;40(1):11–5.

Charleston MA, Perkins SL: Lizards, malaria, and jungles in the Caribbean. In: Page RD, editor. Tangled trees: phylogeny, cospeciation and coevolution. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2003. p. 65–92.

Pérez-Tris J, Hellgren O, Križanauskienė A, Waldenström J, Secondi J, Bonneaud C, et al. Within-host speciation of malaria parasites. PLoS One. 2007;2(2):e235.

Martinsen ES, Perkins SL, Schall JJ. A three-genome phylogeny of malaria parasites (Plasmodium and closely related genera): evolution of life-history traits and host switches. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2008;47(1):261–73.

Gilbert GS, Webb CO. Phylogenetic signal in plant pathogen-host range. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(12):4979–83.

Medeiros MC, Hamer GL, Ricklefs RE. Host compatibility rather than vector–host-encounter rate determines the host range of avian Plasmodium parasites. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2013;280(1760):20122947.

Muñoz J, Ruiz S, Soriguer R, Alcaide M, Viana DS, Roiz D, et al. Feeding patterns of potential West Nile virus vectors in south-west Spain. PLoS One. 2012;7(6):e39549.

Martínez-de la Puente J, Muñoz J, Capelli G, Montarsi F, Soriguer RC, Arnoldi D, et al. Avian malaria parasites in the last supper: identifying encounters between parasites and the invasive Asian mosquito tiger and native mosquito species in Italy. Malar J. 2015;14(1):32.

Aitken THG. An in vitro feeding technique for artificially demonstrating virus transmission by mosquitoes. Mosq News. 1977;37(1):130–3.

Colton L, Biggerstaff BJ, Johnson A, Nasci RS. Quantification of West Nile virus in vector mosquito saliva. J Am Mosquito Contr. 2005;21(1):49–53.

Vazeille M, Mousson L, Martin E, Failloux AB. Orally co-infected Aedes albopictus from La Reunion Island, Indian Ocean, can deliver both dengue and Chikungunya infectious viral particles in their saliva. Plos Negl Trop Dis. 2010;4(6):e706.

Vogels CB, Fros JJ, Göertz GP, Pijlman GP, Koenraadt CJ. Vector competence of northern European Culex pipiens biotypes and hybrids for West Nile virus is differentially affected by temperature. Parasite Vector. 2016;9(1):1.

Golenda CF, Burge R, Schneider I. Plasmodium falciparum and P. berghei: detection of sporozoites and the circumsporozoite proteins in the saliva of Anopheles stephensi mosquitoes. Parasitol Res. 1992;78(7):563–9.

Schall JJ, Vardo AM. Identification of microsatellite markers in Plasmodium mexicanum, a lizard malaria parasite that infects nucleated erythrocytes. Mol Ecol Notes. 2007;7(2):227–9.

Kappe HI, Gardner MJ, Brown SM, Ross J, Matuschewski K, Ribeiro JM, et al. Exploring the transcriptome of the malaria sporozoite stage. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98(17):9895–900.

Palinauskas V, Žiegytė R, Iezhova TA, Ilgūnas M, Bernotienė R, Valkiūnas G. Description, molecular characterisation, diagnostics and life cycle of Plasmodium elongatum (lineage pERIRUB01), the virulent avian malaria parasite. Int J Parasitol. 2016; In press.

Christensen BM, Barnes HJ, Rowley WA. Vertebrate host specificity and experimental vectors of Plasmodium (Novyella) kempi sp. n. from the eastern wild turkey in Iowa. J Wildl Dis. 1983;19(3):204–13.

Kazlauskienė R, Bernotienė R, Palinauskas V, Iezhova TA, Valkiūnas G. Plasmodium relictum (lineages pSGS1 and pGRW11): complete synchronous sporogony in mosquitoes Culex pipiens pipiens. Exp Parasitol. 2013;133(4):454–61.

Dong Y, Manfredini F, Dimopoulos G. Implication of the mosquito midgut microbiota in the defense against malaria parasites. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5(5):e1000423.

Murdock CC, Paaijmans KP, Cox-Foster D, Read AF, Thomas MB. Rethinking vector immunology: the role of environmental temperature in shaping resistance. Nature Rev Microbiol. 2012;10(12):869–76.

Valkiūnas G, Kazlauskienė R, Bernotienė R, Palinauskas V, Iezhova TA. Abortive long-lasting sporogony of two Haemoproteus species (Haemosporida, Haemoproteidae) in the mosquito Ochlerotatus cantans, with perspectives on haemosporidian vector research. Parasitol Res. 2013;112(6):2159–69.

Valkiūnas G, Kazlauskienė R, Bernotienė R, Bukauskaitė D, Palinauskas V, Iezhova TA. Haemoproteus infections (Haemosporida, Haemoproteidae) kill bird-biting mosquitoes. Parasitol Res. 2014;113(3):1011–8.

Valkiūnas G, Liutkevičius G, Iezhova TA. Complete development of three species of Haemoproteus (Haemosporida, Haemoproteidae) in the biting midge Culicoides impunctatus (Diptera, Ceratopogonidae). J Parasitol. 2002;88(5):864–8.

Glaizot O, Fumagalli L, Iritano K, Lalubin F, Van Rooyen J, Christe P. High prevalence and lineage diversity of avian malaria in wild populations of great tits (Parus major) and mosquitoes (Culex pipiens). Plos One. 2012;7(4):e34964.

Larcombe SD, Gauthier-Clerc M. Avian Malaria is absent in juvenile colonial herons (Ardeidae) but not Culex pipiens mosquitoes in the Camargue, Southern France. Waterbirds. 2015;38(4):387–95.

Perez-Tris J, Bensch S. Diagnosing genetically diverse avian malarial infections using mixed-sequence analysis and TA-cloning. Parasitology. 2005;131(01):15–23.

Bernotienė R, Palinauskas V, Iezhova T, Murauskaitė D, Valkiūnas G. Avian haemosporidian parasites (Haemosporida): a comparative analysis of different polymerase chain reaction assays in detection of mixed infections. Exp Parasitol. 2016;163:31–7.

Valkiūnas G, Bensch S, Iezhova TA, Križanauskienė A, Hellgren O, Bolshakov CV. Nested cytochrome b polymerase chain reaction diagnostics underestimate mixed infections of avian blood haemosporidian parasites: microscopy is still essential. J Parasitol. 2006;92(2):418–22.

Acknowledgements

Martina Ferraguti, Alberto Pastoriza, Esmeralda Pérez and Isabel Martín helped during the field and laboratory work. Plácido and Maribel allowed us to sample mosquito larvae in the Cañada de los Pájaros. We would also like to thank the two anonymous reviewers for constructively revising this manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by projects CGL2012-30759 and CGL2015-65055-P from the Spanish Ministerio de Economia y Competitividad and European Regional Development’s funds (FEDER). We acknowledge support of the publication fee by the CSIC Open Access Publication Support Initiative through its Unit of Information Resources for Research (URICI). R.G.L. was supported by a FPI grant (BES-2013-065274), J.M.P. by a Juan de la Cierva contract, L.G. by a contract under the Excelence Projects from Junta de Andalucía (RNM-7800) and J.Y. by a grant from China Scholarship Council.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors’ contributions

RGL, JMP, LG and JF designed the study. RGL, JMP and JY conducted the experimental work. RGL and JMP performed the laboratory analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

All experimental procedures were approved by the CSIC Ethics committee and Animal Health authorities, and complied with Spanish laws.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Gutiérrez-López, R., Martínez-de la Puente, J., Gangoso, L. et al. Do mosquitoes transmit the avian malaria-like parasite Haemoproteus? An experimental test of vector competence using mosquito saliva. Parasites Vectors 9, 609 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-016-1903-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-016-1903-9