Abstract

Invasive fungal infections, particularly those caused by Candida species, are not uncommon in critically ill patients and are associated with considerable morbidity and mortality. Diagnosis and management of these infections can be challenging. In this review, we will briefly discuss recent epidemiological data on invasive candidiasis and current diagnostic approaches before concentrating on antifungal treatments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Invasive fungal infections in critically ill patients are associated with considerable morbidity and mortality. Candida and Aspergillus species are the most frequent causes of healthcare-associated fungal infections in these patients [1]. Although Candida infections are the most frequent fungal infections in ICU patients, invasive aspergillosis is associated with higher morbidity and mortality rates, even in the absence of traditional hematological risk factors [2]. Occasionally, cryptococcosis, pneumocystosis, or zygomycosis may also be encountered in the ICU setting in patients with solid organ or hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, cancer, or hematological malignancies. Because Candida species account for 70–90 % of invasive fungal infections, this overview will focus on invasive candidiasis and the important aspects that must be considered as part of optimizing treatment.

Epidemiology

In the USA, Candida species are responsible for 8–10 % of bloodstream infections (BSI) and are the fourth most common bloodstream pathogen. In Europe, Candida species only account for 2–3 % of BSI and are ranked as the 6th–10th most frequent pathogen [3]. Approximately 30–35 % of all episodes of candidemia occur in ICU patients [4]. In the Extended Prevalence of Infection in Intensive Care (EPIC II) point prevalence study [5], Candida was isolated in 17 % of infected culture-positive patients. Several studies have reported increasing incidence rates of candidemia in ICUs over recent years [6, 7], although population-based studies have suggested reduced incidence rates possibly related to improved infection control practices in high-risk patients [8, 9].

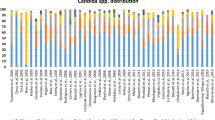

Invasive candidiasis is a highly lethal infection associated with mortality rates between 40 and 60 % [6, 7, 10, 11]. The five most common Candida species are Candida albicans, Candida glabrata, Candida tropicalis, Candida parapsilosis, and Candida krusei [12]. C. albicans was previously the predominant species isolated in patients with invasive candidiasis, accounting for 65–70 % of the total number of Candida isolates. However, the epidemiology has changed in recent years, with non-albicans species now responsible for about half of the cases in some centers [10, 13, 14]. C. parapsilosis tends to be more frequent in southern Europe, Australia, and Latin America than elsewhere [10, 15–17], and C. glabrata is more frequent in the older population than in middle-aged adults [7, 15]. Non-albicans species often have reduced susceptibilities or even intrinsic resistance to azoles or echinocandins [17]. These epidemiological trends underscore the need to perform large longitudinal studies to obtain data that can be used to guide empirical antifungal therapy.

Diagnosis

Prompt and accurate diagnosis of invasive fungal infection is crucial so that appropriate antifungal agents can be started rapidly. However, early diagnosis is not always easy. Microscopic examination is rapid and can be helpful but a negative result does not exclude infection [18, 19]. Blood cultures are positive in only 50–70 % of cases of Candida BSI [20]. Furthermore, it can take several days before Candida is identified at the species level and antifungal susceptibility data are available. Moreover, blood cultures are rarely positive in patients with deep-seated candidiasis [20]. In such patients, cultures of infected tissues can be performed but have their own limitations, including the need for invasive surgical procedures and poor sensitivity [20].

Recently, nonculture-based diagnostic tests have been developed for detection in blood of components of the fungal cell wall (such as mannan and β-d-glucan (BDG)) by immunoassays, of DNA by PCR, and of antibodies by serology. The performance of BDG assays in invasive fungal infections has been assessed in three systematic reviews. In the subgroup of patients with proven infection, the pooled sensitivities and specificities of BDG were 79.1, 87.7, and 78 %, respectively [21–23]. Importantly, BDG assays are not species specific so further tests are needed to identify the specific fungus. In patients with suspected invasive candidiasis, the presence of elevated circulating levels of Candida mannan antigen in the blood had a sensitivity of 58 % and a specificity of 93 % [24]. In the same group of patients, the detection of anti-mannan antibodies had a sensitivity of 59 % and a specificity of 83 %. The sensitivity increased to 83 % when the mannan and anti-mannan assays were combined, but the specificity remained similar at 86 %. PCRs for fungi continue to be challenging for technical reasons and there are no commercially available tests at present. In a review of more than 50 standard, nested, or real-time PCRs [25], the pooled sensitivity and specificity were 95 and 92 %, respectively, for invasive candidiasis.

Combining several markers may prove more useful. A technology combining PCR and nanoparticle-based hybridization, the T2 magnetic resonance-based biosensing technology platform, can detect as little as 1 colony-forming unit/ml of the five most common Candida species [26] and was shown to have an overall specificity of 99.4 % for invasive candidemia [27]. This test is expensive to perform, however, and although costs may be balanced by more accurate earlier diagnosis with reduced administration of antifungal agents and reduced mortality rates [28], further studies are needed to validate its use and assess its cost–benefit ratio.

Risk factors

Numerous risk factors for invasive Candida infections have been identified, including higher Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II scores, diabetes mellitus, renal insufficiency, surgery (especially abdominal surgery), pancreatitis, the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics, parenteral nutrition, hemodialysis, mechanical ventilation, the presence of central vascular catheters, and therapy with immunosuppressive agents [29–34]. The development of invasive Candida infections is often preceded by extensive colonization of the skin or of the mucus membranes of the gastrointestinal and urogenital tracts, and the degree of colonization, assessed using the Colonization Index, has been shown to be an independent risk factor for development of candidiasis [35, 36].

Several prediction rules and scores based on clinical, laboratory, and microbiological parameters have been proposed to help clinicians identify patients at high risk of developing invasive fungal infections [32, 33, 35, 37–41]. Ostrosky-Zeichner et al. [40] proposed a prediction rule characterized by a very high negative predictive value (0.97) and including the following parameters: use of systemic antibiotic therapy, total parenteral nutrition, dialysis, steroids or immunosuppressive agents, major surgery or pancreatitis, and the presence of a central venous catheter. The Candida score, an easy-to-use assessment system proposed by Leon et al. [32, 33], integrates four risk factors (total parenteral nutrition, surgery, multifocal Candida colonization, and severe sepsis) and also has a high negative predictive value (0.98) to rule out invasive candidiasis [33]. However, colonization surveillance cultures are expensive and their precise value remains unclear [42].

More recently, biomarkers of fungal infection have been suggested to assist in decisions to start or stop antifungals. BDG was superior to the Colonization Index or the Candida score for the prediction of intraabdominal candidiasis in high-risk surgical and ICU patients, with a cutoff value of 80 pg/ml [43]. Similarly a prospective observational study demonstrated that BDG was more accurate than the Candida score and the Colonization Index for early prediction of invasive Candida infection in patients at risk for Candida sepsis [44], with 250 pg/ml identified as the best cutoff value [44]. A decrease in BDG levels during antifungal treatment for invasive candidiasis correlated with a successful clinical response with a positive predictive value of 90 % [45]. However, despite its promising performance for excluding invasive infection and orienting the duration of therapy, the cost of the BDG test and a lack of large validation studies currently limit its use.

Management

Antifungal treatment can be considered as prophylactic (in patients at high risk of fungal infection), empiric (triggered by clinical signs of fungal infection, e.g., persistent fever in the presence of risk factors), preemptive (triggered by microbiological or biomarker evidence of fungus without actual infection), and definitive (after positive microbiological confirmation of strain and sensitivity of fungus).

Prophylactic antifungal agents are recommended in just a few specific situations and most treatments are given on an empiric basis [46]. Although use of preemptive therapy is gaining interest, more studies are needed to better define which patients may benefit from this approach [47] and whether more widespread use of antifungal agents may negatively influence fungal ecology [48]. In a recent study of 241 ICU patients requiring emergency gastrointestinal surgery for intraabdominal infection, preemptive therapy with micafungin was not effective at reducing the development of invasive candidiasis compared with placebo, although there was some suggestion that this may have been the result of the preemptive therapy being administered too late [49].

There are three main groups of antifungals: the azoles, the polyenes, and the echinocandins. The selection of an antifungal regimen is based on multiple factors, including epidemiological data, patient characteristics, hospital setting, fungal strain, site of infection, and safety profiles of the antifungal agents. Although different antifungals can show comparable efficacy in treating candidemia, their differences in terms of pharmacokinetics (PK) and pharmacodynamics (PD) (including fungistatic versus fungicidal activity, need for dose adjustment in case of hepatic or renal failure and drug–drug interactions), toxicity, and selection pressure remain significant and can affect the clinical outcome of fragile patient populations, such as the critically ill. Specific guidelines are therefore available to help direct optimal antifungal choices [12, 46, 50]. The European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID) guidelines no longer consider fluconazole the drug of choice for invasive candidiasis, and endorse the use of echinocandins as first-line empiric treatment [46]. The rationale for this statement is that, compared with fluconazole, echinocandins show a broader spectrum of activity, fungicidal activity, an excellent safety profile, and fewer drug–drug interactions. The recent Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) guidelines also recommend echinocandins for initial therapy [12]. All three available echinocandins (caspofungin, micafungin, and anidulafungin) penetrate well into the biofilm formed on vascular devices. Nevertheless, fluconazole remains a well-known and well-tolerated antifungal with a significantly lower cost compared with the echinocandins and may still be of value in clinically stable patients who have had no recent azole exposure or have known fluconazole-sensitive organisms [12].

Dosing of antifungal agents

Pathophysiological changes associated with critical illness can change drug concentrations so that they are significantly different from those observed in noncritically ill patients. In these circumstances, if standard dosing is used, then suboptimal concentrations (either too low or unnecessarily high) may result, putting the patient at risk of clinical failure or drug toxicity. Antifungal agents tend not to be as markedly affected by altered PK in critical illness. The drugs are mostly lipophilic, hepatically metabolized, and with high protein binding. Drugs such as fluconazole are an exception to these characteristics. Use of renal replacement therapy (RRT) can influence the clearance of some antifungal drugs, particularly those that are predominantly eliminated by renal mechanisms, are not highly protein bound, and have low molecular weights, notably the azoles and 5-flucytosine. Moreover, different RRT characteristics, including the specific mode, membrane characteristics, flow rates, and duration of treatment, may influence the effects of RRT on drug PK [51] and should be taken into consideration when evaluating dosing.

From a PD perspective, efficacy for the triazole antifungals is described in terms of the ratio of the area under the concentration–time curve (AUC) to the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC). The echinocandins are mostly described in terms of the ratio of the maximum concentration in a dosing interval (Cmax) to the MIC. Fluconazole is the antifungal for which most of the dosing challenges for critically ill patients exist. Data comparing the PK of fluconazole in critically ill patients and noncritically ill patients show a lower AUC, including both Cmax and minimum concentration during a dosing interval [52]. Lack of achievement of the AUC/MIC target in particular is associated with doses <6 mg/kg, suggesting that standard maintenance dosing should be at this level. In sepsis, interstitial fluid concentrations of fluconazole in tissues, which are commonly the target site of infection, are lower than those in plasma by ~50 % [53]. These data suggest that reduced efficacy may occur in states of microvascular failure. In the presence of RRT, very high drug clearances of fluconazole are common, necessitating even higher doses than in patients with normal renal function. Few data are available regarding altered PK of posaconazole, itraconazole, or isavuconazole in critically ill patients. For voriconazole, the unpredictability of dosing for individual patients tends to mean that critical illness does not in itself result in differences to dosing recommendations—although issues such as drug–drug interactions may be more common in these patients, necessitating more careful dose considerations.

There are only sparse data to suggest that the PK of echinocandins changes significantly in critically ill patients and they are not greatly influenced by RRT. A reduced AUC has been described for anidulafungin and caspofungin with a lower Cmax [52], but this is yet to be correlated with reduced efficacy. Use of adequate loading doses is particularly important for these agents (except micafungin), with caspofungin not even reaching steady-state concentrations by day 3 of treatment [54]. The high protein binding of echinocandins may mean that the presence of hypoalbuminemia could severely alter the PK. Preliminary data for micafungin demonstrate an altered volume of distribution with changes in serum albumin concentrations [55]. There are again few data for the various amphotericin formulations or flucytosine. Table 1 presents a summary guidance based on current understanding of how doses should be adjusted in different subpopulations of critically ill patients. Therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) is likely to play an increasingly important role in our antifungal dosing decisions, and recommendations for when TDM should be used with the different agents available have been published recently [56]. To the best of our knowledge, there are no studies in critically ill patients with invasive fungal infections that have measured the patient outcome benefits of a dose-optimization approach, such as TDM. Until such data become available, results from other patient populations, which support achievement of PK/PD targets and the use of TDM, suggest that we should actively optimize antifungal dosing, including the use of TDM where available [57–60].

Conclusion

Fungal infections are associated with considerable morbidity and mortality in ICU patients. Therapies are often started late because these infections can be difficult to diagnose. Until rapid susceptibility testing is available, empiric therapy should be used based on known patient characteristics, including risk factors, local fungal microbiology patterns, hospital setting, and site of infection. Further data from epidemiological studies are needed to help better define high-risk populations, and thus guide empirical antifungal choices. Further development of PCR and other diagnostic and predictive tests will probably lead to increased use of preemptive therapy, but studies are needed to confirm the beneficial effects of preemptive therapy on outcomes before this approach can be recommended. Dosing needs are different in ICU compared to non-ICU patients but data remain limited, with current evidence suggesting that dosing should be individualized according to patient characteristics in order to ensure optimal outcomes.

Abbreviations

- AUC:

-

Area under the concentration–time curve

- BDG:

-

β-d-Glucan

- BSI:

-

Bloodstream infections

- Cmax:

-

maximum concentration in a dosing interval

- MIC:

-

minimum inhibitory concentration

- PD:

-

Pharmacodynamics

- PK:

-

Pharmacokinetics

- RRT:

-

renal replacement therapy

- TDM:

-

therapeutic drug monitoring

References

Montagna MT, Caggiano G, Lovero G, De Giglio O, Coretti C, Cuna T, et al. Epidemiology of invasive fungal infections in the intensive care unit: results of a multicenter Italian survey (AURORA Project). Infection. 2013;41:645–53.

Burghi G, Lemiale V, Seguin A, Lambert J, Lacroix C, Canet E, et al. Outcomes of mechanically ventilated hematology patients with invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. Intensive Care Med. 2011;37:1605–12.

Mean M, Marchetti O, Calandra T. Bench-to-bedside review: Candida infections in the intensive care unit. Crit Care. 2008;12:204.

Marchetti O, Bille J, Fluckiger U, Eggimann P, Ruef C, Garbino J, et al. Epidemiology of candidemia in Swiss tertiary care hospitals: secular trends, 1991–2000. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38:311–20.

Vincent JL, Rello J, Marshall J, Silva E, Anzueto A, Martin CD, et al. International study of the prevalence and outcomes of infection in intensive care units. JAMA. 2009;302:2323–9.

Colombo AL, Guimaraes T, Sukienik T, Pasqualotto AC, Andreotti R, Queiroz-Telles F, et al. Prognostic factors and historical trends in the epidemiology of candidemia in critically ill patients: an analysis of five multicenter studies sequentially conducted over a 9-year period. Intensive Care Med. 2014;40:1489–98.

Lortholary O, Renaudat C, Sitbon K, Madec Y, Denoeud-Ndam L, Wolff M, et al. Worrisome trends in incidence and mortality of candidemia in intensive care units (Paris area, 2002–2010). Intensive Care Med. 2014;40:1303–12.

Kazak E, Akin H, Ener B, Sigirli D, Ozkan O, Gurcuoglu E, et al. An investigation of Candida species isolated from blood cultures during 17 years in a university hospital. Mycoses. 2014;57:623–9.

Cleveland AA, Harrison LH, Farley MM, Hollick R, Stein B, Chiller TM, et al. Declining incidence of candidemia and the shifting epidemiology of Candida resistance in two US metropolitan areas, 2008–2013: results from population-based surveillance. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0120452.

Bassetti M, Merelli M, Righi E, Diaz-Martin A, Rosello EM, Luzzati R, et al. Epidemiology, species distribution, antifungal susceptibility, and outcome of candidemia across five sites in Italy and Spain. J Clin Microbiol. 2013;51:4167–72.

Leroy O, Bailly S, Gangneux JP, Mira JP, Devos P, Dupont H, et al. Systemic antifungal therapy for proven or suspected invasive candidiasis: the AmarCAND 2 study. Ann Intensive Care. 2016;6:2.

Pappas PG, Kauffman CA, Andes DR, Clancy CJ, Marr KA, Ostrosky-Zeichner L, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the management of candidiasis: 2016 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62:e1–50.

Klingspor L, Tortorano AM, Peman J, Willinger B, Hamal P, Sendid B, et al. Invasive Candida infections in surgical patients in intensive care units: a prospective, multicentre survey initiated by the European Confederation of Medical Mycology (ECMM) (2006–2008). Clin Microbiol Infect. 2015;21:87.e1–10.

Montagna MT, Lovero G, Borghi E, Amato G, Andreoni S, Campion L, et al. Candidemia in intensive care unit: a nationwide prospective observational survey (GISIA-3 study) and review of the European literature from 2000 through 2013. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2014;18:661–74.

Guinea J. Global trends in the distribution of Candida species causing candidemia. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20 Suppl 6:5–10.

Puig-Asensio M, Padilla B, Garnacho-Montero J, Zaragoza O, Aguado JM, Zaragoza R, et al. Epidemiology and predictive factors for early and late mortality in Candida bloodstream infections: a population-based surveillance in Spain. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20:O245–54.

Arendrup MC. Update on antifungal resistance in Aspergillus and Candida. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20 Suppl 6:42–8.

Morace G, Borghi E. Fungal infections in ICU patients: epidemiology and the role of diagnostics. Minerva Anestesiol. 2010;76:950–6.

Schelenz S, Barnes RA, Barton RC, Cleverley JR, Lucas SB, Kibbler CC, et al. British Society for Medical Mycology best practice recommendations for the diagnosis of serious fungal diseases. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15:461–74.

Clancy CJ, Nguyen MH. Finding the “missing 50 %” of invasive candidiasis: how nonculture diagnostics will improve understanding of disease spectrum and transform patient care. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56:1284–92.

Lamoth F, Cruciani M, Mengoli C, Castagnola E, Lortholary O, Richardson M, et al. β-Glucan antigenemia assay for the diagnosis of invasive fungal infections in patients with hematological malignancies: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies from the Third European Conference on Infections in Leukemia (ECIL-3). Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:633–43.

Karageorgopoulos DE, Vouloumanou EK, Ntziora F, Michalopoulos A, Rafailidis PI, Falagas ME. β-D-glucan assay for the diagnosis of invasive fungal infections: a meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:750–70.

He S, Hang JP, Zhang L, Wang F, Zhang DC, Gong FH. A systematic review and meta-analysis of diagnostic accuracy of serum 1,3-β-D-glucan for invasive fungal infection: focus on cutoff levels. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2015;48:351–61.

Mikulska M, Calandra T, Sanguinetti M, Poulain D, Viscoli C. The use of mannan antigen and anti-mannan antibodies in the diagnosis of invasive candidiasis: recommendations from the Third European Conference on Infections in Leukemia. Crit Care. 2010;14:R222.

Avni T, Leibovici L, Paul M. PCR diagnosis of invasive candidiasis: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:665–70.

Neely LA, Audeh M, Phung NA, Min M, Suchocki A, Plourde D, et al. T2 magnetic resonance enables nanoparticle-mediated rapid detection of candidemia in whole blood. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5:182ra54.

Mylonakis E, Clancy CJ, Ostrosky-Zeichner L, Garey KW, Alangaden GJ, Vazquez JA, et al. T2 magnetic resonance assay for the rapid diagnosis of candidemia in whole blood: a clinical trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60:892–9.

Bilir SP, Ferrufino CP, Pfaller MA, Munakata J. The economic impact of rapid Candida species identification by T2Candida among high-risk patients. Future Microbiol. 2015;10:1133–44.

Yang SP, Chen YY, Hsu HS, Wang FD, Chen LY, Fung CP. A risk factor analysis of healthcare-associated fungal infections in an intensive care unit: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:10.

Holley A, Dulhunty J, Blot S, Lipman J, Lobo S, Dancer C, et al. Temporal trends, risk factors and outcomes in albicans and non-albicans candidaemia: an international epidemiological study in four multidisciplinary intensive care units. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2009;33:554–7.

Jorda-Marcos R, Alvarez-Lerma F, Jurado M, Palomar M, Nolla-Salas J, Leon MA, et al. Risk factors for candidaemia in critically ill patients: a prospective surveillance study. Mycoses. 2007;50:302–10.

Leon C, Ruiz-Santana S, Saavedra P, Almirante B, Nolla-Salas J, varez-Lerma F, et al. A bedside scoring system (“Candida score”) for early antifungal treatment in nonneutropenic critically ill patients with Candida colonization. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:730–7.

Leon C, Ruiz-Santana S, Saavedra P, Galvan B, Blanco A, Castro C, et al. Usefulness of the “Candida score” for discriminating between Candida colonization and invasive candidiasis in non-neutropenic critically ill patients: a prospective multicenter study. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:1624–33.

Chakrabarti A, Sood P, Rudramurthy SM, Chen S, Kaur H, Capoor M, et al. Incidence, characteristics and outcome of ICU-acquired candidemia in India. Intensive Care Med. 2015;41:285–95.

Pittet D, Monod M, Suter PM, Frenk E, Auckenthaler R. Candida colonization and subsequent infections in critically ill surgical patients. Ann Surg. 1994;220:751–8.

Eggimann P, Pittet D. Candida colonization index and subsequent infection in critically ill surgical patients: 20 years later. Intensive Care Med. 2014;40:1429–48.

Michalopoulos AS, Geroulanos S, Mentzelopoulos SD. Determinants of candidemia and candidemia-related death in cardiothoracic ICU patients. Chest. 2003;124:2244–55.

Shorr AF, Tabak YP, Johannes RS, Sun X, Spalding J, Kollef MH. Candidemia on presentation to the hospital: development and validation of a risk score. Crit Care. 2009;13:R156.

Paphitou NI, Ostrosky-Zeichner L, Rex JH. Rules for identifying patients at increased risk for candidal infections in the surgical intensive care unit: approach to developing practical criteria for systematic use in antifungal prophylaxis trials. Med Mycol. 2005;43:235–43.

Ostrosky-Zeichner L, Sable C, Sobel J, Alexander BD, Donowitz G, Kan V, et al. Multicenter retrospective development and validation of a clinical prediction rule for nosocomial invasive candidiasis in the intensive care setting. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2007;26:271–6.

Playford EG, Lipman J, Kabir M, McBryde ES, Nimmo GR, Lau A, et al. Assessment of clinical risk predictive rules for invasive candidiasis in a prospective multicentre cohort of ICU patients. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35:2141–5.

Eggimann P, Bille J, Marchetti O. Diagnosis of invasive candidiasis in the ICU. Ann Intensive Care. 2011;1:37.

Tissot F, Lamoth F, Hauser PM, Orasch C, Fluckiger U, Siegemund M, et al. β-Glucan antigenemia anticipates diagnosis of blood culture-negative intraabdominal candidiasis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188:1100–9.

Posteraro B, De Pascale G, Tumbarello M, Torelli R, Pennisi MA, Bello G, et al. Early diagnosis of candidemia in intensive care unit patients with sepsis: a prospective comparison of (1 → 3)-β-D-glucan assay, Candida score, and colonization index. Crit Care. 2011;15:R249.

Jaijakul S, Vazquez JA, Swanson RN, Ostrosky-Zeichner L. (1,3)-β-D-glucan as a prognostic marker of treatment response in invasive candidiasis. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55:521–6.

Cornely OA, Bassetti M, Calandra T, Garbino J, Kullberg BJ, Lortholary O, et al. ESCMID guideline for the diagnosis and management of Candida diseases 2012: non-neutropenic adult patients. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18 Suppl 7:19–37.

Bassetti M, Leon C, Timsit JF. Are prophylactic antifungals in highly colonized patients safe and effective? Intensive Care Med. 2015;41:1336–9.

Ferreira D, Grenouillet F, Blasco G, Samain E, Henon T, Dussaucy A, et al. Outcomes associated with routine systemic antifungal therapy in critically ill patients with Candida colonization. Intensive Care Med. 2015;41:1077–88.

Knitsch W, Vincent JL, Utzolino S, Francois B, Dinya T, Dimopoulos G, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of preemptive antifungal therapy for the prevention of invasive candidiasis following gastrointestinal surgery for intra-abdominal infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61:1671–8.

Bassetti M, Marchetti M, Chakrabarti A, Colizza S, Garnacho-Montero J, Kett DH, et al. A research agenda on the management of intra-abdominal candidiasis: results from a consensus of multinational experts. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39:2092–106.

Fish DN. Antifungal dosing in dialysis and continuous renal replacement therapy. Curr Fungal Infect Rep. 2011;5:75–82.

Sinnollareddy MG, Roberts JA, Lipman J, Akova M, Bassetti M, De Waele JJ, et al. Pharmacokinetic variability and exposures of fluconazole, anidulafungin, and caspofungin in intensive care unit patients: data from multinational Defining Antibiotic Levels in Intensive care unit (DALI) patients study. Crit Care. 2015;19:33.

Sinnollareddy MG, Roberts MS, Lipman J, Lassig-Smith M, Starr T, Robertson T, et al. Determination of subcutaneous interstitial fluid penetration and pharmacokinetics of fluconazole in intensive care unit patients with sepsis using in vivo microdialysis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;60:827–32.

Muilwijk EW, Schouten JA, van Leeuwen HJ, van Zanten AR, de Lange DW, Colbers A, et al. Pharmacokinetics of caspofungin in ICU patients. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014;69:3294–9.

Grau S, Luque S, Campillo N, Samso E, Rodriguez U, Garcia-Bernedo CA, et al. Plasma and peritoneal fluid population pharmacokinetics of micafungin in post-surgical patients with severe peritonitis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2015;70:2854–61.

Ashbee HR, Barnes RA, Johnson EM, Richardson MD, Gorton R, Hope WW. Therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) of antifungal agents: guidelines from the British Society for Medical Mycology. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014;69:1162–76.

Park WB, Kim NH, Kim KH, Lee SH, Nam WS, Yoon SH, et al. The effect of therapeutic drug monitoring on safety and efficacy of voriconazole in invasive fungal infections: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55:1080–7.

Dolton MJ, Ray JE, Marriott D, McLachlan AJ. Posaconazole exposure-response relationship: evaluating the utility of therapeutic drug monitoring. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:2806–13.

Brosh-Nissimov T, Ben-Ami R. Differential association of fluconazole dose and dose/MIC ratio with mortality in patients with Candida albicans and non-albicans bloodstream infection. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2015;21:1011–7.

van der Elst KC, Brouwers CH, van den Heuvel ER, van Wanrooy MJ, Uges DR, van der Werf TS, et al. Subtherapeutic posaconazole exposure and treatment outcome in patients with invasive fungal disease. Ther Drug Monit. 2015;37:766–71.

Acknowledgements

JAR is funded by a Career Development Fellowship from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (APP1048652) and would like to acknowledge funding from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia for a Centre for Research Excellence (APP1099452).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

TC has received research grants and consultant and speaker’s bureau incomes paid to his institution from Abbott, Astellas, bioMérieux, Merck Sharp & Dohme (MSD)-Chibret, Novartis, Pfizer, and Roche Diagnostics. JAR is on the advisory board for Infectopharm (IV fosfomycin) and lectures for MSD (posaconazole). MA has received research grants from MSD, Pfizer, Cubist, and Toray; and participated in the Advisory board for Basilea and Cubist. MB serves on scientific advisory boards and/or has received funding for research, travel, or speaker honoraria from Bayer, Pfizer, MSD, Astellas, Basilea, Tetraphase, Gilead, Novartis, Achaogen, Paretek, Medicine Company, and Angelini. J-LV declares that he has no conflicts of interest.

Authors’ contributions

Each author drafted a specific section of the manuscript and all authors then critically revised the whole for intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Calandra, T., Roberts, J.A., Antonelli, M. et al. Diagnosis and management of invasive candidiasis in the ICU: an updated approach to an old enemy. Crit Care 20, 125 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-016-1313-6

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-016-1313-6