Abstract

Background

Aboriginal and Torres Islander Australians experience considerably higher rates of diabetes and diabetes related foot complications and amputations than non-Indigenous Australians. Therefore there is a need to identify aspects of Aboriginal and Torres Islander focussed foot health programs that have had successful outcomes in reducing diabetes related foot complications. Wider knowledge and implementation of these programs may help reduce the high burden of diabetes related foot disease experienced by Aboriginal and Torres Islander Australians.

Methods

PubMeD, Informit Indigenous collection, CINAHL, SCOPUS, the Cochrane Library and grey literature sources were searched to 28th August 2018. We included any published reports or studies of stand-alone diabetes related foot care interventions, programs, services, educational resources or assessment of these interventions, designed for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians.

Results

Thirteen studies detailing interventions in the Northern Territory, New South Wales, Queensland and Western Australia met the inclusion criteria. Five reports described delivery of podiatry services while the other eight investigated educational and training programs. Half of the reports related to aspects of the Indigenous Diabetic Foot program which provides culturally appropriate foot education and training workshops for health care providers. One article reported quantitative data related to clinical patient outcome measures.

Conclusions

No state- or nation-wide foot health programs for prevention of diabetes related foot complications in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians were identified. One program achieved high adherence to the national guidelines regarding timing of podiatry review treatments through use of an evidence based foot risk classification tool and provision of services in a culturally appropriate centre.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Diabetes mellitus is one of the fastest growing chronic diseases in the world [1]. Aboriginal and Torres Islander Australians experience four times the rate of diabetes compared to non-Indigenous Australians, with an overall incidence of 13% [2], and rates as high as 42% reported in some remote communities [3]. As the leading cause of lower limb amputation, and with high rates of associated mortality, diabetes related foot complications are a major but poorly recognised health care burden in Australia, estimated to cost in excess of $1.6 billion annually [4, 5]. Evidence demonstrates Aboriginal and Torres Islander Australians have a three to six fold increased risk of diabetes related foot complications including neuropathy, foot ulcer and lower limb amputation compared to non-Indigenous Australians [6, 7].

Consequently the National Health and Medical Research Council Guidelines for the prevention of foot complications in diabetes state that ‘Until adequately assessed all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with diabetes are considered to be at high risk of developing foot complications and therefore will require foot checks at every clinical encounter and active follow-up’ [8]. International guidelines suggest that up to 85% of diabetes related amputations could be prevented with early detection of problems and appropriate treatment [9]. Despite the evident need for effective preventative foot care in this population, available data indicate poor engagement with existing preventative care services in contrast to high rates of related hospitalisation and amputation [6, 7, 10].

A number of examples of culturally safe services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities in Australia have increased access to combined diabetes care services and improved patient outcomes [11,12,13,14,15,16,17]. These share common characteristics, including community consultation in the development, implementation and ongoing management of the service; involvement of Aboriginal Health Workers (AHW); and a focus on self-management and patient participation in health through improved health literacy. There is an obvious and urgent need to identify similarly successful stand-alone foot health programs for the prevention of diabetes related foot complications in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians.

Methods

An electronic database search of PubMeD (using Lit.search https://www.lowitja.org.au/litsearch from the Lowitja Institute which was developed as a search tool for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health articles), Informit Indigenous collection, CINAHL, SCOPUS, and the Cochrane Library was conducted from database inception to 28th August 2018. Additional hand searches of grey literature sources were also conducted including of the Lowitja Institute, Menzies School of Health Research, Australian Indigenous HealthInfoNet (www.healthinfonet.ecu.edu.au), Services for Australian Rural and Remote Allied Health (www.sarrah.org.au), and the Australia Institute of Health and Welfare (http://www.aihw.gov.au/). Reference lists of included studies, clinical guidelines and review articles were also searched. Authors of included studies and reports were contacted where intentions of further evaluation was stated, and, where information was provided, it has been included in this review. The PubMed search strategy as generated from the Lowitja Institute is detailed in Additional file 1. Inclusion criteria were any published reports of stand-alone diabetes related foot care interventions, programs, services, educational resources or assessment of these interventions, designed for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians. Interventions were excluded if foot care was embedded within a broader health program due to likelihood of variability in the extent and reporting of the foot care component, and, the confounding effect of the broader health care program on foot specific outcomes. Foot care programs not designed specifically for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians were also excluded. One reviewer conducted the electronic searches (AS). Titles and abstracts were independently assessed by two reviewers (AS and VC). Disagreements were resolved by consensus and a third reviewer where necessary (MW).

Extraction of the study data and assessment of the methodological quality of the included studies was conducted by two authors (AS and VC) using the Observational Study and Qualitative Study Appraisal Checklists designed by Health Evidence Bulletins – Wales [18]. These checklists are designed for critical appraisal of observational and qualitative studies and were selected as they include a small number of key domains, are simple checklists rather than scales and were developed using a variety of literature sources [19].

Results

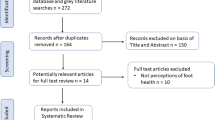

The database and literature search resulted in a total of 1305 citations of which 75 were appropriate for full text review (Fig. 1). After review, 13 articles met the inclusion criteria (Table 1), and 62 studies were excluded (Additional file 2). The methodological quality of the included articles is detailed in Tables 2 and 3. Five articles were reports providing overviews of services provided or materials produced so quality assessment was not considered appropriate [20,21,22,23,24]. Of the remaining articles, two were qualitative studies [25, 26] and six were cohort or cross-sectional studies [27,28,29,30,31,32]. All of the studies provided detailed information regarding the population studied and aims of the investigations. One of the studies reviewed mainly hospital-based renal dialysis patients, which could make comparison to wider community-based populations difficult [30]. None of the trials reported any cost information related to development or implementation of the interventions.

Flow chart diagram of systematic review inclusion and exclusion process. ATSI: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander, Combined programs: diabetes or chronic disease programs with a foot health component, review articles: including guideline documents and systematic reviews, no foot program: health interventions without a foot health component

The thirteen articles detailed foot programs which were conducted in New South Wales (NSW), Queensland (QLD), Western Australia (WA) and the Northern Territory (NT) with the majority in rural, regional or remote areas (Table 1). Five of the articles described delivery of podiatry services to Aboriginal communities [20,21,22, 27, 28, 33], three described the development of specific foot education resources [23, 24, 26], and the remaining five assessed foot educational and training programs [25, 29,30,31,32]. Seven of the thirteen reports described aspects of the Indigenous Diabetic Foot Program (IDFP) [21, 24, 25, 29,30,31,32].

Delivery of podiatry services

Moorditj Djena is an Aboriginal podiatry outreach program implemented in 2011 in metropolitan Perth, WA, which was initially funded as part of the Australian Federal Government’s ‘Closing the Gap’ program [27, 34]. The program’s aim is to identify, manage and prevent foot complications and to improve diabetes self-management. Culturally secure treatment is offered in community venues as well as two customised mobile vans. Staff include AHWs, podiatrists and diabetes educators. An initial review of the program describes the number of clients seen, occasions of service, percentage of local Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander clients with diabetes seen by the clinic (14.5%), and staff perceptions of the program.

One study outlines the findings from a retrospective 26 month (2012 to 2014) clinical audit undertaken at the Albury-Wodonga Aboriginal Health Service (AHS) in NSW. [28] Podiatry services only commenced at the health service in 2011 and the audit’s aim was to determine if evidence based standards for podiatry services based on the patients risk classification were being met. In the sample population (n = 729) a high rate (94%) of adherence to the national guidelines regarding podiatric review timeframes was found. The authors suggested that the excellent outcomes may be due to provision of services according to national guidelines, in a culturally safe manner, alongside flexible arrangements such as drop in appointments and access to transport services [28].

The establishment of podiatry outreach services in remote communities is described by three reports [20,21,22]. The Yirrkala Health Centre in East Arnhem Land NT, organised an inaugural Diabetes Day in 2005 to coincide with a visit from a podiatrist and AHW specialising in diabetes education [22]. Clients received podiatry services on the day and were registered for recall according to their risk status, and both staff and clients received diabetes related foot education. Another two reports detail the establishment of visiting podiatry services (for 26 weeks a year) to fourteen remote communities to the east and west of Alice Springs NT [21, 33]. The program, which started in 2009, is based on the IDFP and is funded by the NT Primary Healthcare Network’s (PHN) Medical Outreach Indigenous Chronic Disease Program. A podiatrist and an Aboriginal podiatry assistant provide general podiatry services, foot health checks, and education in foot first aid, diabetic foot care and footwear. Between 2014 and 2017, activity report data from the NT PHN Outreach Services demonstrated the number of patients receiving podiatric care increased by 167% [33]. The increased attendance rate is anecdotally credited to the close relationships the team built with each community, in conjunction with a personalised and targeted approach to encouraging people to attend clinics and self-manage their foot health. A similar visiting podiatry service was established by the Cherbourg Regional Aboriginal and Islander Community Controlled Health Service in QLD, with funding provided by the Australian Government Rural Health Outreach Fund [20]. The podiatrist visits twenty times a year and also encourages attendance for an annual diabetes neurovascular foot assessment. The program is supported by the medical community with the local general practitioner (GP) providing follow-up care and referrals to specialists as required.

Development of foot educational resources

The Indigenous Diabetic Foot Program (IDFP) is the most widely used template for delivery of diabetes related podiatry services to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians. The IDFP was developed in QLD in 2005 to provide culturally appropriate foot education for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians and training workshops for AHWs and podiatrists regarding diabetic foot screening [24, 35]. The education resources developed for clients are mostly visual aids (posters, a CD ROM, videos and an educational card set), which feature Aboriginal feet and stories. Resources for AHWs and podiatrists include a Diabetic Foot Assessment of Risk (DART) form, a self-care education model for use with clients, and advice on referral pathways if required. The DART form requires assessment of the foot (pulses, sensation, foot lesions and deformities, amputations or scars), assessment of client self-care practices (awareness of the need for foot care, wearing footwear, and ability for self-care), assessment of an overall risk classification and a date for future foot review.

The development of culturally sensitive visual educational resources for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians are described by two studies [23, 26]. Two diabetes foot care movies (‘Bran nue leg’ and ‘Deadly (and not in a good way)’) were produced as part of a larger High Risk Foot intervention in WA [23]. An Aboriginal media company and local Kimberly community members were involved in production of the movies, ensuring the message was delivered in a culturally sensitive manner. The aim was to improve health literacy related to at-risk feet, and encourage early presentation to health services for foot problems by Aboriginal Australians in the Kimberley. The report described the recent development and release of the movies and we did not identify any follow up report of the evaluation or effectiveness of the movies. Another study details the processes behind the creation of a foot care educational tool for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians in the NT [26]. The preferred educational resource, a graphical flip-chart, was determined following a workshop and a series of focus groups with health professionals (including general practitioners, nurses, and AHWs) and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians with diabetes. Again, the study was published prior to the release of the materials, and assessment of the effectiveness of the tool was not identified in this review.

Assessment of foot educational and training programs

Assessment of aspects of the IDFP is described by five reports [25, 29,30,31,32]. One study conducted focus groups with 60 Aboriginal Elders, health workers, students and nurses, to determine their preferred messages and media for communication of diabetes foot care information [25]. The paper-based resources produced by the IDFP, with photographs of feet of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, were the participants’ favoured option.

The other four studies describe training and evaluation of AHWs knowledge and competency when using the IDFP [29,30,31,32]. One report described a protocol for a two-day IDFP workshop in QLD to teach AHWs how to screen for diabetes related foot problems. Follow up investigations included telephone questionnaires with AHWs, examination of completed DART forms and comparison of completed DART forms versus number of people in the community with diabetes [29]. No published assessment of the workshop was identified during this search. Another report describes the evaluation of the IDFP in a hospital site and four remote communities in the Pilbara WA [30]. Workshop attendees completed a workshop evaluation form and DART forms completed in the hospital were cross-checked by a podiatrist. Community members were assessed regarding their perceptions of the course as well as knowledge and self-care for diabetic feet. Feedback suggested that the program was culturally safe and improvements were seen in community member’s knowledge and self-care pre and post course. An assessment of AHWs perceptions of the IDFP following a one day course and integration of the tools into practice was also conducted on the Lower Mid Coast of NSW [32]. The participants had higher knowledge and confidence levels immediately after and six months after the workshop. Just over half (55%) of participants implemented the DART screening form into clinical practice, however none had implemented a ‘Look after your feet workshop’, which is one of the patient education components of the IDFP. While an increase in the number of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people attending the podiatrist was also reported, this could not be attributed to the effects of the training as the number of referrals from course attendees was not tracked. The final report describes a two-day IDFP workshop run in the Lower Gulf area in QLD to train AHWs in screening diabetic feet [31]. Following the training, the AHWs implemented the DART form as a standard for all clients with diabetes.

Discussion

The aim of this review was to systematically evaluate the current literature to determine the availability and effectiveness of stand-alone foot health programs for the prevention of diabetes related foot complications in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians.

While national and state governments have developed general Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health plans and strategies, no state- or nation-wide foot health programs for prevention of diabetes related foot complications were identified in the literature. Benefits of existing foot care programs for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are therefore largely restricted to the area/s in which they are delivered. Of the thirteen reports that met the inclusion criteria (Table 1), one detailed quantitative data related to clinical patient outcome measures following implementation of the program [28]. The most widely used program, the IDFP (Indigenous Diabetic Foot Program), has been assessed with regard to workshop attendee competency and client perceptions of the educational material provided. Evaluation of the IDFP’s impact in terms of patient outcomes and rates of diabetes related foot complications is yet to be undertaken/published [35].

Despite years of research, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians still have worse health outcomes than non-Indigenous Australians. A key criticism of the research to date, both in Australia and in Indigenous populations of other countries, is a high concentration of descriptive research regarding populations, risks and measures, rather than a focus on assessment of the efficacy of interventions to close the health outcome gap [36, 37]. To enable an intervention to be successfully and widely implemented by front-line clinicians it must meet rigorously designed methodological standards, it must have been tested for its effectiveness and reproducibility, and it must be easily accessible in peer reviewed literature [36]. While six of thirteen reports (46%) in this review do describe interventions, only one (8%) of the reports [28] describes patient based clinical outcomes following implementation of a podiatry service. Overall, methodological quality of the studies that were eligible to be assessed was mixed. Lack of robust assessment of outcome data, including comparison to control data in relation to patient outcomes, was common to all studies. In addition, reporting of economic analysis related to development or implementation of the interventions was not provided in any study. Lack of documented follow-up evaluation of interventions, similar to that seen in the stand-alone foot programs in this review, has been described previously. A report investigating the implementation of 1082 Australian Indigenous health, cultural and education programs, found only 8% of programs were evaluated [38]. Additionally, in contrast to non-Indigenous health interventions, the majority of the reports included in this review were published in non-peer reviewed grey literature. These factors make it challenging for clinicians and researchers to locate and implement best practice evidence in relation to foot health programs for the prevention of diabetes related foot complications in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians.

Although assessment of clinical outcomes following implementation of foot health strategies has not been commonplace in the past that seems to be changing. The current lack of evidence regarding successful components of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander focussed foot health programs in reducing diabetes related foot complications has been clearly recognised by those working in clinical areas. Programs and assessments that are currently underway have incorporated clinical and cost outcomes as part of their implementation plans. In WA the Moorditj Djena program [27] has recently conducted an internal review, the results of which will be published upon completion (private correspondence). The review includes a data linkage project to examine participant outcomes pre and post enrolment in the program. In particular, they examined the population reach of the program, the reach in high-risk settings, occasions of service versus comorbidity, and the number and duration of hospitalisations for diabetes-related conditions. NSW Health is currently in the planning stages of a Healthy Deadly Foot initiative (private correspondence). It has the potential to be the largest foot health program for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians implemented to date. One metropolitan local health district (Central Coast), three rural and regional local health districts (Hunter New England, Illawarra Shoalhaven, Western NSW), and one speciality network (St. Vincent’s Health Network) have committed to the project. Goals include the development of AHW roles in local health districts and Aboriginal communities, delivery of appropriate cultural and clinical support, encouraging more Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to train as podiatrists and an evaluation strategy to examine the outcomes of the project. In addition, in 2018, the authors of this report embedded an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander foot health clinic into the undergraduate podiatry program at the University of Newcastle. The clinic, led by an Aboriginal podiatrist and AHW, provides prevention and management services for diabetic foot complications for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians in the local community. It also provides clinical placement to all undergraduate podiatry students as a mechanism to increase cultural awareness in the future podiatry workforce. The service is currently undergoing clinical and educational outcome evaluation for peer-reviewed publication. This includes evaluation of service utilisation with historical control data for the broader clinical service, effectiveness of diabetes education for improving client knowledge of diabetes self-care, and post-placement changes in self-perceived confidence in provision of culturally safe care in undergraduate students.

The results of this review should be viewed in light of several limitations. Although this review was designed to be comprehensive with a robust search on relevant databases, the search strategy may not have located all Australian health initiatives involving diabetes related foot disease specifically delivered for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians. Many of these reports are located in grey literature sources and structured search engines are not available. Additionally, this review only describes programs where reports regarding the development, implementation, or effectiveness of initiatives were publically available. It is likely that programs exist that have not been published in any form; this is particularly probable where these involve individual practitioners, or are in small service delivery models.

Conclusions

No state- or nation-wide foot health programs for prevention of diabetes related foot complications in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians were identified by this review. One report, a clinical audit of podiatry services offered at a NSW AHS, provided data supporting the clinical effectiveness of the program. The authors describe a high rate of adherence to the national guidelines regarding timing of podiatry appointments which may be related to classification of patients according to evidence based risk status, and provision of services in a culturally safe manner. More data regarding aspects of successful Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander foot programs should soon become available with planning and assessment of programs already underway in both WA and NSW.

Abbreviations

- ACCHS:

-

Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services

- AHS:

-

Aboriginal health service

- AHW:

-

Aboriginal health worker

- DART:

-

Diabetic Foot Assessment of Risk form

- DM:

-

Diabetes mellitus

- GP:

-

General Practitioner

- IDFP:

-

Indigenous diabetic foot program

- NSW:

-

New South Wales

- NT:

-

Northern Territory

- QLD:

-

Queensland

- WA:

-

Western Australia

References

World Health Organization. Global report on diabetes. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016.

Diabetes snapshot [Internet]. Australian Government; 2018 [28th July 2018]. Available from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/diabetes/diabetes-snapshot/contents/how-many-australians-have-diabetes.

Mobbs R, Nguyen HT, Bell A. The chronic disease self-management project at Katherine West health board aboriginal Corporation in the Northern Territory: a report of the first year. Aust J Prim Health. 2003;9(2–3):160–7.

Lazzarini PA. The burden of foot disease in inpatient populations: PhD by Publication. Queensland: Queensland University of Technology; 2016.

Lazzarini PA, Gurr JM, Rogers JR, Schox A, Bergin SM. Diabetes foot disease: the Cinderella of Australian diabetes management? J Foot Ankle Res. 2012;5(1):24.

West M, Chuter V, Munteanu S, Hawke F. Defining the gap: a systematic review of the difference in rates of diabetes-related foot complications in aboriginal and Torres Strait islander Australians and non-indigenous Australians. J Foot Ankle Res. 2017;10:48.

Norman PE, Schoen DE, Gurr JM, Kolybaba ML. High rates of amputation among indigenous people in Western Australia. Med J Aust. 2010;192(7):421.

National Evidence-Based Guideline on Prevention, Identification and Management of Foot Complications in Diabetes (Part of the Guidelines on Management of Type 2 Diabetes). Melbourne; 2011.

Bakker K, Apelqvist J, Schaper NC. Practical guidelines on the management and prevention of the diabetic foot 2011. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2012;28(Suppl 1):225–31.

West M, Chuter V, Follent D, Hawke F. Utilisation of public podiatry and diabetes services by the aboriginal and Torres Strait islander community of the central coast of NSW. Aust Indigenous Health Bull. 2016;16:4.

Bailie R, Si D, Dowden M, O'Donoghue L, Connors C, Robinson G, et al. Improving organisational systems for diabetes care in Australian indigenous communities. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007;7:67.

McDermott R, Segal L. Cost impact of improved primary level diabetes care in remote Australian indigenous communities. Aust J Prim Health. 2006;12(2):124–30.

McDermott R, Tulip F, Schmidt B, Sinha A. Sustaining better diabetes care in remote indigenous Australian communities. BMJ. 2003;327(7412):428–30.

McDermott RA, Schmidt B, Preece C, Owens V, Taylor S, Ming L, et al. Community health workers improve diabetes care in remote Australian indigenous communities: results of a pragmatic cluster randomized controlled trial. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15(1):1–8.

Cooper J, Moore S, Palmer L, Reinhardt J, Roberts M, Solomon A, et al. Partnership approach to indigenous primary health care and diabetes: a case study from regional New South Wales. Aust J Rural Health. 2007;15(1):67–70.

Pearce S, Thomas A-M, Gorman D. The better living diabetes project. Aboriginal Isl Health Worker J. 2005;29(1):4–6.

Tyrrell M, Grundy J, Lynch P, Wakerman J. Laramba diabetes project: an evaluation of a participatory project in a remote Northern Territory community. Health Promot J Aust. 2003;14(1):48–53.

Weightman A, Mann M, Sander L, Turley R. Health evidence bulletins Wales: a systematic approach to identifying the evidence. Project Methodology 5. Cardiff: Information Services UWCM; 2004.

Sanderson S, Tatt ID, Higgins JPT. Tools for assessing quality and susceptibility to bias in observational studies in epidemiology: a systematic review and annotated bibliography. Int J Epidemiol. 2007;36(3):666–76.

Podiatry service in Cherbourg kicking goals in diabetes foot care. Outreach IMPACT 2016;(3). https://www.checkup.org.au/icms_docs/254242_IMPACT_Issue_3.pdf

Coombes S. A model of podiatry care in remote Central Australia. Darwin: 13th National Rural Health Conference; 2015.

Turner J. Diabetes health in East Arnhem Land – from the feet up. Aboriginal Isl Health Worker J. 2006;30(1):21–3.

Schoen DE, Thompson SC. Diabetes foot care education movies for aboriginal people: bran nue leg. Health Promot J Austr. 2016;27(1):88–9.

Warnock J. SARRAH’s: indigenous diabetic foot project. Aboriginal Isl Health Worker J. 2004;28(5):31.

Schoen D, Balchin D, Thompson S. Health promotion resources for aboriginal people: lessons learned from consultation and evaluation of diabetes foot care resources. Health Promot J Austr. 2010;21(1):64–9.

Watson J, Obersteller EA, Rennie L, Whitbread C. Diabetic foot care: developing culturally appropriate educational tools for aboriginal and Torres Strait islander peoples in the Northern Territory, Australia. Aust J Rural Health. 2001;9(3):121–6.

Ballestas T, McEvoy S, Swift-Otero V, Unsworth M. A metropolitan aboriginal podiatry and diabetes outreach clinic to ameliorate foot-related complications in aboriginal people. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2014;38(5):492–3.

Blatchford L, Morey P, McConigley R. Identifying type 2 diabetes risk classification systems and recommendations for review of podiatric care in an Australian aboriginal health clinic. J Foot Ankle Res. 2015;8:34.

Connors R. Who stops the footrot? Interviews with Aboriginal health workers trained in Indigenous Diabetic Foot Health program. Yeppoon: The National SARRAH Conference; 2008.

Bandaranaike A. Stamping out diabetic foot in the Pilbara, Western Australia. Broome: 2010 SARRAH National Conference; 2010.

Radowski C, Willett C, Thomas C, Wisely R. Implementing the indigenous diabetic foot project in the lower gulf of Australia. Poster presentation. J Foot Ankle Res. 2011;4(Suppl 1):P46.

Townsend E. Evaluation of the NSW indigenous diabetic foot program for health workers whose primary role is with aboriginal people in the lower mid north coast. Aust Indigenous Health Bull. 2012;12:2.

Coombes S. A step in the right direction. Australian Healthcare & Hospitals Association (AHHA) Health Advocate; 2017. https://ahha.asn.au/system/files/docs/publications/feb2017_tha_web.pdf

South & North Metropolitan Health Services - Moorditj Djena – ‘Strong Feet’. Diabetes WA 3rd Annual Aboriginal Health Forum; 2015.

Services for Australian Rural and Remote Allied Health. Addressing Diabetes-Related Foot Disease in Indigenous NSW. A Scan of Available Evidence. Canberra: Research report prepared for NSW Ministry of Health, workforce development and planning branch; 2016.

Paul CL, Sanson-Fisher R, Stewart J, Anderson AE. Being sorry is not enough: the sorry state of the evidence base for improving the health of indigenous populations. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38(5):566–8.

Bainbridge R, Tsey K, McCalman J, Kinchin I, Saunders V, Lui F, et al. No one’s discussing the elephant in the room: contemplating questions of research impact and benefit in aboriginal and Torres Strait islander Australian health research. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:696.

Hudson S. Evaluating indigenous programs: a toolkit for change. Sydney: Centre for Independent Studies; 2017.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Associate Professor Sara Jones (University of South Australia), Dr. Suzanne McEvoy (Western Australian Health), Mrs. Sara Coombes (Twinkle Toes Podiatry), Mr. Hassan Kadous (NSW Ministry of Health), Mr. Charles Davison (NSW Ministry of Health) and Ms. Georgina Frank (Podiatry Department, Concord Hospital) for providing information regarding the programs in this review.

Funding

This research was supported by funding from the School of Health Sciences, University of Newcastle.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

VC and FH conceived the study. AS conducted the electronic searches. AS, VC and MW assessed the abstracts and included articles. All authors revised and provided significant input to the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

PubMed search strategy as generated from the Lowitja Institute. (DOCX 28 kb)

Additional file 2:

Excluded studies. (DOCX 13 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Chuter, V., West, M., Hawke, F. et al. Where do we stand? The availability and efficacy of diabetes related foot health programs for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians: a systematic review. J Foot Ankle Res 12, 17 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13047-019-0326-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13047-019-0326-1