Abstract

Background

Cities are a major source of atmospheric CO2; however, understanding the surface CO2 exchange processes that determine the net CO2 flux emitted from each city is challenging owing to the high heterogeneity of urban land use. Therefore, this study investigates the spatiotemporal variations of urban CO2 flux over the Seoul Capital Area, South Korea from 2017 to 2018, using CO2 flux measurements at nine sites with different urban land-use types (baseline, residential, old town residential, commercial, and vegetation areas).

Results

Annual CO2 flux significantly varied from 1.09 kg C m− 2 year− 1 at the baseline site to 16.28 kg C m− 2 year− 1 at the old town residential site in the Seoul Capital Area. Monthly CO2 flux variations were closely correlated with the vegetation activity (r = − 0.61) at all sites; however, its correlation with building energy usage differed for each land-use type (r = 0.72 at residential sites and r = 0.34 at commercial sites). Diurnal CO2 flux variations were mostly correlated with traffic volume at all sites (r = 0.8); however, its correlation with the floating population was the opposite at residential (r = − 0.44) and commercial (r = 0.80) sites. Additionally, the hourly CO2 flux was highly related to temperature. At the vegetation site, as the temperature exceeded 24 ℃, the sensitivity of CO2 absorption to temperature increased 7.44-fold than that at the previous temperature. Conversely, the CO2 flux of non-vegetation sites increased when the temperature was less than or exceeded the 18 ℃ baseline, being three-times more sensitive to cold temperatures than hot ones. On average, non-vegetation urban sites emitted 0.45 g C m− 2 h− 1 of CO2 throughout the year, regardless of the temperature.

Conclusions

Our results demonstrated that most urban areas acted as CO2 emission sources in all time zones; however, the CO2 flux characteristics varied extensively based on urban land-use types, even within cities. Therefore, multiple observations from various land-use types are essential for identifying the comprehensive CO2 cycle of each city to develop effective urban CO2 reduction policies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The global atmospheric CO2 concentration has exceeded 400 ppm since 2013 because of the increasing use of fossil fuels [1]. Currently, more than 70% of the CO2 emissions from fossil fuel combustion occur in cities [2, 3]. Although cities are major sources of atmospheric CO2, they also present a major opportunity to reduce atmospheric CO2. The net CO2 flux from cities results from the combined effects of anthropogenic emissions and vegetation uptake [4]. Therefore, understanding the comprehensive surface CO2 exchange processes, including CO2 sources and sinks, is a prerequisite for developing effective policies to reduce net CO2 flux from cities.

Traditionally, inventory data that estimate CO2 emissions based on fossil fuel consumption statistics are utilized to understand variations in CO2 flux emitted from cities worldwide [5,6,7]. Recently developed sophisticated inventory data have facilitated the identification of CO2 emission characteristics at the building and road scales according to each emission sector [7]. However, these spatiotemporally high-resolution inventory data were only established for a limited number of cities. For most cities, aggregated inventory data at the municipal scale cannot fully reflect the spatiotemporal heterogeneity of CO2 characteristics. Moreover, the current state of data will not be available until at least one or two years from now [1, 8]. Additionally, there are substantial uncertainties in the city-level inventories because of various emission sources and insufficient statistical data within cities [9, 10]. Gurney et al. [11] suggested that 48 cities in the United States under-reported their emissions by 18.3%. This means that although inventory data enables quantification of urban CO2 emissions, solely using this data poses limitations on the appropriate management of urban CO2 emissions.

To supplement the inventory data and improve the understanding of real-time urban CO2 variability, CO2 observation networks have been established in many cities; studies based on these observations have been conducted actively [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21]. Among them, CO2 flux observations through eddy covariance (EC) directly measure the net CO2 exchange rate per unit area [22]. Initially, EC observations were used to measure the CO2 flux in a vegetated area [23]. EC observations over urban areas have increased with the increasing importance of understanding urban net CO2 flux [12, 13, 15, 17, 20, 24,25,26,27]. EC observations in cities provide various information on the complex CO2 exchange processes as the EC-based CO2 flux represents the integrated response of CO2 to anthropogenic emissions, vegetation uptake, and meteorological conditions [22, 28].

Using the characteristics of CO2 flux data, previous studies quantified the net CO2 flux in multiple cities and analyzed the regional heterogeneity of the CO2 flux. Stagakis et al. [20] quantified the annual CO2 flux in Heraklion, Greece as 5.29 kg C m− 2 year− 1 and determined the contribution of multiple sources (i.e., vehicle, heating, and human respiration) to CO2 flux. CO2 flux observations in London, Helsinki, Beijing, and Vancouver showed that they emit 12.72, 1.76, 4.90, and 6.71 kg C m− 2 year− 1 of CO2 per year, respectively, serving as significant CO2 sources [12, 13, 15, 24]. Moreover, Ueyama and Ando [17] found that the CO2 flux varies greatly, from 0.5 to 4.9 kg C m− 2 year− 1, in Sakai (Japan) depending on the degree of urbanization. According to the CO2 flux measurements in Seoul, South Korea, residential areas emit 40 times more CO2 than urban park areas during the non-growing season (March) [25]. Accordingly, recent studies have shown different CO2 flux characteristics within and between cities because of various land-use types. Therefore, more urban EC measurements need to be conducted [29]. Additionally, most previous studies used a limited number of observation sites (one to three); consequently, understanding the spatiotemporal characteristics of the CO2 flux according to various land-use types in a city remains challenging.

Therefore, this study investigated the EC-based CO2 flux data measured at nine sites with different urban land-use types around the Seoul Capital Area, South Korea, the world’s largest carbon-producing urban agglomeration, and aimed to improve the understanding of the CO2 cycle in urban areas with various surface characteristics [21, 30,31,32,33]. The specific objectives of this study were to: (1) quantify the CO2 flux over the Seoul Capital Area considering different urban land-use types (baseline, residential, old town residential, commercial, and vegetation areas), (2) understand the characteristics of temporal CO2 flux variations for each surface type, and (3) evaluate the driving factors of CO2 flux variations.

Methods

Nine sites around the Seoul Capital Area

Seoul, South Korea, one of the largest megacities in East Asia, is a densely populated city, with approximately 25 million residents in the Seoul Capital Area, more than 50% of the total population of the country [34]. Seoul has a temperate climate, with a minimum monthly mean temperature of − 2.4 ℃ in January and a maximum monthly mean temperature of 25.7 ℃ in August (data from 1981 to 2010) according to the Korea Meteorological Administration (KMA) [35]. The annual mean precipitation is 1450.5 mm, with more than 60% occurring in the summer (June, July, and August).

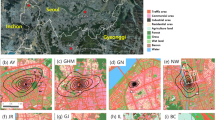

In this study, measurements at nine sites around the Seoul Capital Area were used to study the spatiotemporal variations in the urban CO2 flux [36]. Each observation site was located at a place representative of different urban land-use types based on the surrounding topography and geography (Table 1; Fig. 1). Among the nine sites, Songdo (SGD; 37.383° N, 126.655° E) was used as the baseline site. This site is located at the end of the west coast of South Korea and has minimal impact on CO2 emissions from the Seoul Capital Area. By selecting SGD, which is also characterized by reduced vegetation and human activities, as a baseline site, we attempted to contrast variation of CO2 flux at urban sites characterized by considerable vegetation and intensive residential and commercial activities with those of areas that are not.

The other sites were broadly classified into three land-use types: residential, commercial, and vegetation areas. For land-use type determination, we used a 1 m spatial resolution land-cover map created by the Ministry of Environment [37]. The land-use type of each site was defined as the most dominant land-use type, except for roads and urban vegetation, within a 1 km radius of the observation site. Jungnang (JNG; 37.591° N, 127.079° E), Gajwa (GJW; 37.584° N, 126.914° E), and Seongnam (SGN; 37.441° N, 127.142° E) were classified as residential areas. Unlike JNG and GJW, SGN consists of low-rise old town residential areas with low combustion efficiency. Among all buildings in SGN, only 7% of them were built after 2000 according to the GIS building integrated information provided by the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport [38]. In contrast, in JNG and GJW, more than 23% of all buildings were constructed after 2000. Gwanghwamun (GHM; 37.572° N, 126.978° E), Anyang (ANY; 37.394° N, 126.960° E), Nowon (NOW; 37.654° N, 127.056° E), and Gangnam (GAN; 37.520° N, 127.022° E) were classified as commercial areas. A land-cover map for Ilsan (ILS; 37.685° N, 126.731° E) was unavailable as it is located near a military base. However, as more than 70% of the area within a 1 km radius of ILS is farmland according to satellite imagery, we defined ILS as a vegetation area (Fig. 1).

The footprint of each site was calculated using the analytical footprint model from Kormann and Meixer [39]; the average footprint of each site was calculated by averaging the daily mean footprints for the entire study period (January 2017 to December 2018; Fig. 2). The model indicates that the majority of the flux at each site originated within 200–500 m of the EC tower. The footprint area affecting each site consisted of regions representing the land-use type of each site. Although there were differences in the footprint areas of each site, the surrounding land-use types were homogeneously distributed; this meant that CO2 flux observations represented each land-use type irrespective of the footprint area.

Instrumentation and data processing instrumentation and data processing

Fourteen EC observation systems have been operated by the National Institute of Meteorological Sciences (NIMS) since 2013. The EC tower observation system is equipped with an open path gas analyzer (EC150, Campbell Scientific Inc.) and sonic anemometer (CSAT3A, Campbell Scientific Inc.). The open path gas analyzer, which measures atmospheric CO2 concentrations and water vapor, is calibrated every 6 months. The sonic anemometer directly measures three orthogonal wind components and the speed of sound. The EC towers are installed on the roof of each observation site (Table 1). Observations were made at a temporal resolution of 10 Hz for each EC tower; the 10 Hz raw data were pre-processed to 30 min-averaged flux data after four key procedures were conducted by NIMS: (1) verification of the physical limit; (2) removal of spike data [40]; (3) calculation of 30 min-averaged vertical flux [41]; and (4) Webb-Pearman-Leuning correction [42, 43]. Each EC tower observation system is built with integrated meteorological sensors to observe fundamental weather variables including temperature and precipitation. For more information on the observation system and data pre-processing, refer to Park et al. [36].

In this study, two-year data were used from January 2017 to December 2018, when continuous observations were recorded at all sites. For the study period, we filtered the data collected at the 14 EC observation sites using half-hourly CO2 flux data pre-processed by the NIMS. Data filtering was conducted sequentially as follows: (1) CO2 flux data measured when the CO2 concentration was lower than the 1st percentile of that at the SGD baseline site were removed as the local urban effect of the observation site could not be well captured; (2) CO2 flux data measured during precipitation events and when the instrument malfunctioned were removed manually; (3) negative CO2 flux values measured at night (21:00–03:00) were removed as they were considered to be erroneous; and (4) major outliers were statistically filtered using the interquartile range method [44]. Here, major outliers considerably deviating from other values were removed as they were considered to poorly represent the surrounding environment of each site. Among the 14 EC observation sites, only the 9 sites with more than 80% data remaining after filtering were considered for analysis. The data coverage of the selected sites was 86.80% during the study period. For values with a period of missing data of less than 2 days, gap-filling was conducted in two stages: (1) if the missing period was shorter than 2 h, the missing value was reconstructed by linear interpolation of the values 1 h before and after the missing time; (2) if the missing period was more than 2 h and less than 2 days, the missing value was reconstructed using the mean diurnal variation of 3 days before and after the observation date. Gap-filling was not conducted for periods with data missing for longer than 2 days. After gap-filling, the EC data coverage at each observation site was at least 94%. Full data coverage (100% data availability) was achieved at all sites except at JNG (96.03%), ANY (94.25%), GAN (99.18%), and SGD (97.82%; Fig. 3).

Ancillary data

To examine how each factor affected the monthly CO2 flux variability, normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) and building gas-usage data were studied. Floating population, traffic volume, and temperature data were used to determine the factors causing diurnal variations in the CO2 flux.

We used the NDVI data from the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) sensor onboard the Terra satellite to assess the monthly correlation between the CO2 flux and vegetation activity [45]. Level 3 MODIS Vegetation Indices (MOD13Q1) Version 6 generates NDVI data every 16 days at a grid resolution of 250 m. We obtained the NDVI grid values within a 1 km radius from each CO2 flux site. The extracted average monthly NDVI values for each site were analyzed. The SGD site is located on coastal reclaimed land; therefore, the NDVI data were not calculated. Along with the NDVI data, building gas-usage, which is one of the largest sources of direct CO2 emissions over Seoul, was used to represent human activity [46]. Monthly building gas-usage data were obtained from the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport and can be downloaded from the Architectural Data System [47]. We utilized the total gas usage of all buildings except power plants in the administrative districts of each CO2 flux site during the study period.

Hourly floating population and traffic volume data are only observed within the administrative district of Seoul by the Seoul Metropolitan Government [48, 49]. Thus, we only used data for the JNG, GJW, GHM, NOW, and GAN sites, which are located in the administrative district of Seoul. The floating population data were calculated using the hourly mobile-phone LTE signals from certain points [50]. The total floating population data within the administrative district of each CO2 flux site were used. Traffic volume data were considered as inflows and outflows of vehicles for certain road sections. As the traffic volume is constant on a monthly basis, traffic volume data were only utilized for the analysis of diurnal variations in the CO2 flux. We used the traffic volume data measured at the closest point from each site. Observation points for the traffic volume of each site, located at places where the average traffic flow of nearby areas can be well captured, were 450 m to 2.4 km away from each CO2 flux site.

CO2 emission data for each site calculated from the inventory data were utilized to compare the observation-based CO2 flux and inventory-based CO2 emission datasets. Due to the absence of high spatiotemporal resolution CO2 inventory data for Seoul, the Open-Data Inventory for Anthropogenic Carbon dioxide (ODIAC) data was used. This dataset contains the highest resolution data available for Seoul, provided by the National Institute for Environmental Studies (NIES) in Japan [51]. This study used the latest version of ODIAC (ODIAC2020b), which provides monthly total fossil fuel CO2 emissions data with a spatial resolution of 1 km [52]; CO2 emission data closest to each observation site were utilized.

Results

The Hovmöller diagram of the CO2 flux by day (x-axis) and time of day (y-axis) at the nine sites shows distinct differences in the temporal CO2 flux variations at each site in the Seoul Capital Area according to the land-use type (Fig. 3). Although there were clear seasonal and diurnal variations in the CO2 flux across all sites, their amplitudes and periods varied for each site. We further analyzed the spatiotemporal variations of the CO2 flux, as described in the following sections.

Spatial variations

The average annual CO2 fluxes of each site in 2017 and 2018 significantly varied from 1.09 to 16.28 kg C m− 2 year− 1 according to the urban land-use type in the city. The average annual CO2 fluxes were the lowest in SGD (baseline site; 1.09 kg C m− 2 year− 1) and ILS (vegetation site; 1.65 kg C m− 2 year− 1; Fig. 4). Residential sites JNG, GJW, and SGN showed annual CO2 fluxes of 7.38, 3.23, and 16.28 kg C m− 2 year− 1, respectively. The commercial sites GHM, ANY, NOW, and GAN showed annual CO2 fluxes of 5.45, 7.47, 4.59, and 6.04 kg C m− 2 year− 1, respectively. On average, the CO2 flux of residential and commercial sites (7.20 kg C m− 2 year− 1) was seven times that of the baseline site and four times that of the vegetation site. In particular, the CO2 flux of the old town residential site (SGN) was three times that of other residential sites (5.30 kg C m− 2 year− 1). Although the amount of emitted CO2 differed for each site, all sites, including the vegetation and baseline sites, served as CO2 sources.

Monthly variations

All sites had clear seasonal variations with the lowest CO2 flux in the summer and the highest CO2 flux in the winter (Fig. 5). In general, the average CO2 flux for all sites was the lowest in August (0.42 g C m− 2 h− 1) and the highest in January (1.18 g C m− 2 h− 1). In summer, all sites released three times lower CO2 than in winter; however, even in summer, all sites, including the ILS vegetation site, had a positive CO2 flux. This indicates that all urban land-use types act as CO2 sources throughout the year. The highest seasonal amplitude (3.72 g C m− 2 h− 1), which is the difference between the monthly minimum and maximum CO2 fluxes, was observed at the SGN site. SGN emitted nine times more CO2 in winter than that in summer. The lowest seasonal amplitude was observed at the SGD baseline site (0.084 g C m− 2 h− 1). SGD released a relatively constant level of CO2 throughout the year compared to other sites.

To identify potential factors affecting monthly CO2 flux variations, relationships between CO2 flux and factors representing human activities and vegetation were assessed (Fig. 6). As traffic in the Seoul Capital Area does not substantially vary over the year, building energy usage, accounting for more than 70% of fossil fuel usage in Seoul, was used as the human activity factor [46]. Along with the human activity factor, the NDVI value represented the vegetation photosynthesis capacity and efficiency [53]. The monthly CO2 flux of all land-use types was positively correlated with the building gas usage and negatively correlated with NDVI data (Fig. 6). The correlation coefficient between the CO2 flux and building gas usage was relatively high in residential areas (r = 0.72, p < 0.1) and low in commercial areas (r = 0.34, p < 0.1). This was because of the different patterns of building gas usage in residential and commercial areas. In commercial areas, the maximum building gas usage in winter was similar to or less than that in summer. However, in residential areas, the maximum building gas usage in winter was considerably greater than that in summer (data not shown). On average, the NDVI values and CO2 flux showed a correlation coefficient of 0.61 at all sites, with the highest correlation coefficient of 0.79 at the ILS vegetation site. To further examine the effect of vegetation and building gas usage on the monthly variations in the CO2 flux, the relationship of the CO2 flux in each season with NDVI and building gas usage were analyzed (Fig. 7). In summer, sites with high NDVI values showed low CO2 flux values (r = − 0.70; Fig. 7a). In winter, sites with high building gas usage presented high CO2 flux values (r = 0.57; Fig. 7b). In particular, the CO2 absorption and emission by vegetation in summer and building gas usage in winter, respectively, play a vital role in the distinct monthly CO2 flux variations. The GAN site relatively deviated from the general trends of other sites as this was located near a river and was affected by strong atmospheric mixing.

a Scatter plot of the monthly CO2 flux averaged during summer in accordance with the average monthly NDVI value during summer for each site. The solid line represents the linear regression between the CO2 flux and NDVI. b Scatter plot of the monthly CO2 flux averaged during winter in accordance with the average monthly building gas usage during winter for each site. The solid line represents the linear regression between the CO2 flux and building gas usage

a Scatter plot of the hourly CO2 flux in accordance with the temperature for non-vegetation urban (gray) and vegetation (red) sites from 2017 to 2018. The black solid line represents the median value of the CO2 flux of all urban sites except for the vegetation site; the red solid line represents the CO2 flux of the vegetation site. The gray vertical lines represent 18 and 24 ℃ (solid and dashed, respectively), which are threshold temperatures for non-vegetated and vegetated sites, respectively. b The same as a but with a narrower y-axis range.

Diurnal variations in each season

Diurnal patterns of the CO2 flux were similar in all seasons; however, notable differences existed between urban land-use types (Fig. 8). On average, the diurnal cycle of the CO2 flux in residential areas showed a distinct bimodal cycle, with maximum CO2 fluxes at 08:00 and 19:00 (local time) and minimum fluxes at 03:00 and 14:00 (Fig. 8a and d). In contrast, commercial areas had a relatively unimodal diurnal cycle, with a minimum at 04:00 and maximum at 12:00 (Fig. 8b and e). The vegetation area showed a diurnal variation with minimum and maximum CO2 fluxes at 13:00 and 00:00, respectively, in both summer and winter (Fig. 8c and f). However, the diurnal cycle was much clearer during the summer than that during winter. In the vegetation area, a negative CO2 flux value of − 0.36 C g m− 2 h− 1 occurred during the daytime (08:00–17:00), which was the only period with more CO2 absorption than emission.

To understand the causes of these diurnal variations in the CO2 flux, we compared them with the floating population and traffic volume data, which represented the major human activities (Fig. 9). In addition to human activities, the relationship between the CO2 flux and temperature was also examined to identify the meteorological effect. The CO2 flux in residential areas was negatively correlated with the floating population, while that in commercial areas was positively correlated with the floating population. This difference was attributed to the opposite diurnal cycle of the floating population in each area. In residential areas, the floating population was lower during the daytime than that at night; however, in commercial areas, the diurnal variation of the floating population showed the opposite trend (data not shown). Traffic volume and CO2 flux were positively correlated with a high average correlation coefficient of 0.8 in both residential and commercial areas. The CO2 flux and temperature were positively correlated in most non-vegetation sites. However, only the ILS vegetation site showed a negative correlation between the CO2 flux and temperature.

To understand variations in the correlation between the temperature and CO2 flux at each site, we compared the hourly CO2 flux with temperature, as shown in Fig. 10. The hourly temperature and CO2 flux presented different relationships based on the threshold of 18 ℃ in non-vegetated sites. In most non-vegetated urban sites, the CO2 flux increased as the temperature decreased below 18 ℃ (on average, by 0.026 C g m− 2 h− 1 ℃−1; p < 0.1), and it also increased as the temperature exceeded 18 ℃ (by 0.0074 g m− 2 h− 1 ℃−1; p < 0.1). Given that the threshold temperature of heating in Seoul is 18 ℃, as determined by the KMA, this result indicates that the CO2 flux data reflected the effect of the changing energy use owing to heating and cooling systems. For the vegetation site, the CO2 flux decreased as the temperature increased; however, the decreasing trend of the CO2 flux significantly increased once the temperature exceeded 24 ℃. The sensitivity of CO2 absorption to temperature increased from − 0.0075 to 0.056 C g m− 2 h− 1 ℃−1, a 7.44-fold increase compared with that of the previous temperature, as the temperature exceeded 24 ℃. This result is also consistent with that of a previous study, which showed that the amount of photosynthesis increases as the temperature increases to a certain level [54].

Discussion

In this study, we analyzed CO2 flux observations at nine urban sites with different landscapes in the Seoul Capital Area for the first time. According to the results, the Seoul Capital Area showed substantially different CO2 flux levels, from 1.09 to 16.28 kg C m− 2 year− 1 among different land-use types. Previous studies showed various amounts of CO2 flux in different cities: 5.29 kg C m− 2 year− 1 in Heraklion, Greece; 12.72 kg C m− 2 year− 1 in London, England; 1.76 kg C m− 2 year− 1 in Helsinki, Finland; 4.90 kg C m− 2 year− 1 in Beijing, China; and 6.71 kg C m− 2 year− 1 in Vancouver, Canada [12, 13, 15, 20, 24]. Compared to those in previous studies, the regional differences in CO2 flux within the Seoul Capital Area were greater than those between cities. This indicates a considerable diversity in CO2 flux within cities.

Overall, in residential and commercial areas, where human activities are concentrated, CO2 emissions was five times higher than that in the vegetation and baseline areas. Among them, the total CO2 flux per year in SGN, an old town residential area comprising old buildings with low combustion efficiency, were over three times higher than those in other relatively new residential areas, JNG and GJW. Most CO2 emission from SGN occurred in the winter, reflecting the use of fossil fuels for winter heating. This indicates that heating-related CO2 can be greatly affected by the year of building construction, which is related to the combustion efficiency. Unlike non-vegetation urban areas, the ILS vegetation area absorbed CO2 during the daytime in summer. The average total amount of CO2 absorbed in the vegetation area during daytime (08:00–17:00) was 2.26 g C m− 2 d− 1. Considering that a highly vegetated suburban area of Baltimore, Maryland, USA, absorbs 1.25 g C m− 2 d− 1 of CO2 during daytime in the summer [55], we inferred that carbon uptake by vegetation actively occurs in ILS. However, this amount of CO2 absorbed during the daytime in summer is insufficient to eliminate the 3.37 g C m− 2 d− 1 of CO2 emissions at night from this region. This indicates that the amount of CO2 absorbed in urban vegetation areas is insufficient to balance the CO2 emissions from the city.

Previous studies that analyzed the cause of the variations in the CO2 flux in a city with limited observation sites showed that the CO2 flux in the city was mostly affected by the volume of traffic and vegetation area [12, 13, 15, 17, 20]. However, according to the results of this study obtained using multiple observation sites, the degree to which each driving factor (i.e., building energy usage, NDVI, floating population, traffic volume, and temperature) affects the CO2 flux variations varied for each urban land-use type. This result can only be obtained by using multiple observation sites. This also demonstrates that conducting CO2 flux observations in various locations across a city is necessary to determine the cause of variation in urban CO2 flux.

Expansion of the urban CO2 flux observation sites also enables cross-validation of inventory-based CO2 emissions. We compared the observation-based monthly CO2 flux data from this study with the inventory-based monthly CO2 emission data for each observation site (Fig. 11). This comparison was conducted for the winter (December, January, and February) and summer (June, July, and August) seasons, when vegetation had the least and greatest impact on observation-based CO2 flux data. The results of the winter season highlighted a substantial difference between the inventory-based CO2 emission and observation-based CO2 flux, with the exception of ANY, where there was only an 8.19 g C m− 2 mon− 1 difference between the two datasets (Fig. 11a). Aside from SGD and SGN, inventory-based CO2 emissions tended to be overestimated compared to observation-based CO2 flux; for example, the inventory-based CO2 emissions was 104.29 g C m− 2 mon− 1 greater at JNG, while it was 1316.54 g C m− 2 mon− 1 higher at GHM. By contrast, SGN was the only site where inventory-based CO2 emissions were an underestimate of observation-based CO2 flux. This may be because the high CO2 emissions due to the low combustion efficiency of SGN is not reflected in the inventory data. In the case of summer, on average, CO2 emission from the inventory data was overestimated by 694.40 g C m− 2 mon− 1 than the observation-based CO2 flux (Fig. 11b), which was more than twice larger than that of the winter (286.87 g C m− 2 mon− 1). Unlike inventory-based CO2 emission data, as the vegetation activity is reflected in the observation-based CO2 flux data, the difference between the two datasets could be widened in the summer when vegetation uptake is most active during the year. SGD has a 120.65 g C m− 2 mon− 1 and 71.36 g C m− 2 mon− 1 of observation-based CO2 flux for winter and summer seasons; however, the inventory determines its emissions to be zero as it is located on the coast, making it a difficult site to use for comparison.

These results indicate that variations in CO2 emission characteristics that may not be reflected in inventory data, may be identified through EC observations. This suggests that observation-based CO2 flux data may be used to evaluate actual CO2 emission characteristics at a specific location in real-time; however, EC observations cannot be conducted in all areas of the city. By contrast, inventory data is advantageous as it can consistently quantify and manage CO2 emissions in all regions. This means more accurate CO2 emission characteristics of an urban area may be reproduced by narrowing the gap between inventory-based CO2 emissions and observation-based CO2 flux through cross-validation.

The vegetation and non-vegetation urban areas showed different relationships between the hourly CO2 flux and temperature. In the vegetation area, the decreasing trend of CO2 flux significantly increased at 24 ℃, indicating that CO2 absorption from photosynthesis increased rapidly after the temperature increased above a certain level. Non-vegetation urban areas showed the opposite correlation between the CO2 flux and temperature based on the 18 ℃ threshold. This result indicates that CO2 emissions have different sensitivities to cold and hot temperatures, being over three times more sensitive to cold temperatures. In Seoul, 18 ℃ is the threshold temperature for indoor heating, suggesting that the relationship between the CO2 flux and temperature is related to the energy use from building heating and cooling. In fact, the gas usage of buildings in non-vegetated urban sites peaked in the summer and winter, when the temperature was the highest and lowest of the year, respectively. Furthermore, this result is consistent with the v-shaped temperature dependence pattern of energy demand, which is high at low and high temperatures [56]. Based on the threshold temperature for heating and cooling demands (Tb), a lower temperature indicates heating demand, and a higher temperature indicates cooling demand. The energy demand at Tb is the amount of energy that is used consistently regardless of temperature. Applying this energy demand concept to our results showed that CO2 emissions in the Seoul Capital Area were more sensitive to the heating demand than to the cooling demand. Additionally, an average of 0.45 g C m− 2 h− 1 of CO2 was emitted from the Seoul Capital Area from the use of fixed energy, regardless of the temperature.

Conclusions

Global warming has caused extreme variabilities in weather conditions, including unprecedented heat and cold waves [57, 58]. Based on the relationship between temperature and CO2 emissions from our study, CO2 emissions from urban areas are expected to increase as extreme weather conditions become more frequent. In particular, the sensitivity of CO2 emissions to temperature fluctuations from global warming will be the greatest in places such as the old town residential area, where CO2 emissions from heating are more than three times greater than those in other areas. However, this also implies that if urban planning is implemented to improve the energy efficiency of the old downtown area, CO2 emissions from the city can be effectively reduced. As climate change intensifies, the management of old downtown areas with low energy efficiency should be prioritized.

This study demonstrates that to identify the comprehensive CO2 flux characteristics of cities, observations are required for each area to reflect the complexities of urban land-use types. As a novel study, we improved the understanding of the CO2 flux characteristics according to urban land-use types using multiple CO2 flux observations from various urban landscapes. The CO2 flux characteristics derived in this study can help policymakers to develop effective CO2 reduction policies, thereby enabling cities to play important roles in mitigating climate change.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets of the land cover map, GIS building integrated information, NDVI, ODIAC, building energy usage, traffic volume, and floating population supporting the conclusions of this article are available at: https://egis.me.go.kr/, http://www.nsdi.go.kr/, https://earthdata.nasa.gov/, https://db.cger.nies.go.jp/dataset/ODIAC/, https://open.eais.go.kr/, http://topis.seoul.go.kr/, and https://data.seoul.go.kr/, respectively. CO2 flux and temperature data from the eddy covariance observation system are available from the data developers upon request.

Abbreviations

- CO2 :

-

Carbon dioxide

- EC:

-

Eddy covariance

- KMA:

-

Korea Meteorological Administration

- SGD:

-

Songdo

- JNG:

-

Jungnang

- GJW:

-

Gajwa

- SGN:

-

Seongnam

- GHM:

-

Gwanghwamun

- ANY:

-

Anyang

- NOW:

-

Nowon

- GAN:

-

Gangnam

- ILS:

-

Ilsan

- NIMS:

-

National Institute of Meteorological Sciences

- NDVI:

-

Normalized Difference Vegetation Index

- ODIAC:

-

Open-Data Inventory for Anthropogenic Carbon dioxide

- NIES:

-

National Institute for Environmental Studies, Japan

- MODIS:

-

Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer

- Tb :

-

threshold temperature between heating demand and cooling demand

References

Friedlingstein P, Jones MW, O’sullivan M, Andrew RM, Hauck J, Peters GP, et al. Global carbon budget 2019. Earth Syst Sci Data. 2019;11(4):1783–838.

Duren RM, Miller CE. Measuring the carbon emissions of megacities. Nat Clim Change. 2012;2(8):560–2.

Schwandner FM, Gunson MR, Miller CE, Carn SA, Eldering A, Krings T, et al. Spaceborne detection of localized carbon dioxide sources. Science. 2017;358:6360.

Hutyra LR, Duren R, Gurney KR, Grimm N, Kort EA, Larson E, et al. Urbanization and the carbon cycle: Current capabilities and research outlook from the natural sciences perspective. Earths Future. 2014;2(10):473–95.

Baldasano JM, Soriano C, Boada Ls. Emission inventory for greenhouse gases in the City of Barcelona, 1987–1996. Atmos Environ. 1999;33(23):3765–75.

Liu Z, Geng Y, Xue B. Inventorying energy-related CO2 for city: Shanghai study. Energy Proc. 2011;5:2303–7.

Gurney KR, Razlivanov I, Song Y, Zhou Y, Benes B, Abdul-Massih M. Quantification of fossil fuel CO2 emissions on the building/street scale for a large US city. Environ Sci Technol. 2012;46(21):12194–202.

Han P, Cai Q, Oda T, Zeng N, Shan Y, Lin X, Liu D. Assessing the recent impact of COVID-19 on carbon emissions from China using domestic economic data. Sci Total Environ. 2021;750:141688.

Rypdal K, Winiwarter W. Uncertainties in greenhouse gas emission inventories—evaluation, comparability and implications. Environ Sci Policy. 2001;4(2–3):107–16.

Bader N, Bleischwitz R. Measuring urban greenhouse gas emissions: the challenge of comparability. SAPI EN S Surv Perspect Integr Environ Soc. 2009; 2.3.

Gurney KR, Liang J, Roest G, Song Y, Mueller K, Lauvaux T. Under-reporting of greenhouse gas emissions in US cities. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):1–7.

Järvi L, Nordbo A, Junninen H, Riikonen A, Moilanen J, Nikinmaa E, et al. Seasonal and annual variation of carbon dioxide surface fluxes in Helsinki, Finland, in 2006–2010. Atmos Chem Phys. 2012;12(18):8475–89.

Liu H, Feng J, Järvi L, Vesala T. Four-year (2006–2009) eddy covariance measurements of CO2 flux over an urban area in Beijing. Atmos Chem Phys. 2012;12(17):7881–92.

Kort EA, Angevine WM, Duren R, Miller CE. Surface observations for monitoring urban fossil fuel CO2 emissions: minimum site location requirements for the Los Angeles megacity. J Geophys Research: Atmos. 2013;118(3):1577–84.

Ward H, Kotthaus S, Grimmond C, Bjorkegren A, Wilkinson M, Morrison W, et al. Effects of urban density on carbon dioxide exchanges: observations of dense urban, suburban and woodland areas of southern England. Environ Pollut. 2015;198:186–200.

Chandra N, Lal S, Venkataramani S, Patra PK, Sheel V. Temporal variations of atmospheric CO 2 and CO at Ahmedabad in western India. Atmos Chem Phys. 2016;16(10):6153–73.

Ueyama M, Ando T. Diurnal, weekly, seasonal, and spatial variabilities in carbon dioxide flux in different urban landscapes in Sakai, Japan. Atmos Chem Phys. 2016;16(22):14727–40.

Verhulst KR, Karion A, Kim J, Salameh PK, Keeling RF, Newman S, et al. Carbon dioxide and methane measurements from the Los Angeles Megacity Carbon Project–Part 1: calibration, urban enhancements, and uncertainty estimates. Atmos Chem Phys. 2017;17(13):8313–41.

Xueref-Remy I, Dieudonné E, Vuillemin C, Lopez M, Lac C, Schmidt M, et al. Diurnal, synoptic and seasonal variability of atmospheric CO 2 in the Paris megacity area. Atmos Chem Phys. 2018;18(5):3335–62.

Stagakis S, Chrysoulakis N, Spyridakis N, Feigenwinter C, Vogt R. Eddy Covariance measurements and source partitioning of CO2 emissions in an urban environment: application for Heraklion, Greece. Atmos Environ. 2019;201:278–92.

Park C, Jeong S, Park H, Woo J-H, Sim S, Kim J, et al. Challenges in monitoring atmospheric CO2 concentrations in Seoul using low-cost sensors. Asia-Pac J Atmos Sci. 2020:1–7.

Feigenwinter C, Vogt R, Christen A. Eddy covariance measurements over urban areas. Eddy Covariance: Springer; 2012. pp. 377–97.

Baldocchi D, Falge E, Gu L, Olson R, Hollinger D, Running S, et al. FLUXNET: A new tool to study the temporal and spatial variability of ecosystem-scale carbon dioxide, water vapor, and energy flux densities. Bull Am Meteorol Soc. 2001;82(11):2415–34.

Christen A, Coops N, Crawford B, Kellett R, Liss K, Olchovski I, et al. Validation of modeled carbon-dioxide emissions from an urban neighborhood with direct eddy-covariance measurements. Atmos Environ. 2011;45(33):6057–69.

Park M-S, Joo SJ, Lee CS. Effects of an urban park and residential area on the atmospheric CO 2 concentration and flux in Seoul, Korea. Adv Atmos Sci. 2013;30(2):503–14.

Park M-S, Joo SJ, Park S-U. Carbon dioxide concentration and flux in an urban residential area in Seoul, Korea. Adv Atmos Sci. 2014;31(5):1101–12.

Björkegren A, Grimmond C. Net carbon dioxide emissions from central London. Urban Clim. 2018;23:131–58.

Vogt R, Christen A, Rotach M, Roth M, Satyanarayana A. Temporal dynamics of CO 2 fluxes and profiles over a Central European city. Theoret Appl Climatol. 2006;84(1):117–26.

Grimmond CSB, King T, Cropley F, Nowak D, Souch C. Local-scale fluxes of carbon dioxide in urban environments: methodological challenges and results from Chicago. Environ Pollut. 2002;116:243-S54.

Moran D, Kanemoto K, Jiborn M, Wood R, Többen J, Seto KC. Carbon footprints of 13 000 cities. Environ Res Lett. 2018;13(6):064041.

Nangini C, Peregon A, Ciais P, Weddige U, Vogel F, Wang J, et al. A global dataset of CO2 emissions and ancillary data related to emissions for 343 cities. Sci data. 2019;6(1):1–29.

Park C, Jeong S, Park H, Yun J, Liu J. Evaluation of the potential use of satellite-derived XCO 2 in detecting CO 2 enhancement in megacities with limited ground observations: a case study in Seoul using orbiting carbon Observatory-2. Asia-Pac J Atmos Sci. 2021;57(2):289–99.

Park C, Jeong S, Shin Y-S, Cha Y-S, Lee H-C. Reduction in urban atmospheric CO2 enhancement in Seoul, South Korea, resulting from social distancing policies during the COVID-19 pandemic. Atmos Pollut Res. 2021;12(9):101176.

The data set of population of South Korea; Statistics Korea. https://www.index.go.kr/potal/main/EachDtlPageDetail.do?idx_cd=1007. Accessed 09 Dec 2021.

The data set of climate of Seoul; Korea meteorological administration. https://www.weather.go.kr/w/obs-climate/climate/korea-climate/regional-char.do. Accessed 31 Mar 2021.

Park M-S, Park S-H, Chae J-H, Choi M-H, Song Y, Kang M, et al. High-resolution urban observation network for user-specific meteorological information service in the Seoul Metropolitan Area, South Korea. Atmos Meas Tech. 2017;10(4):1575–94.

The data set. of land cover map; Ministry of Environment. https://egis.me.go.kr/. Accessed 31 Mar 2021.

The data set of GIS building integrated information; Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport. http://www.nsdi.go.kr/. Accessed 31 Mar 2021.

Kormann R, Meixner FX. An analytical footprint model for non-neutral stratification. Bound Layer Meteorol. 2001;99(2):207–24.

Vickers D, Mahrt L. Quality control and flux sampling problems for tower and aircraft data. J Atmos Ocean Technol. 1997;14(3):512–26.

Kwon TH, Park MS, Yi C, Choi YJ. Effects of different averaging operators on the urban turbulent fluxes. Atmosphere. 2014;24(2):197–206.

Webb EK, Pearman GI, Leuning R. Correction of flux measurements for density effects due to heat and water vapour transfer. Q J R Meteorol Soc. 1980;106(447):85–100.

Leuning R. The correct form of the Webb, Pearman and Leuning equation for eddy fluxes of trace gases in steady and non-steady state, horizontally homogeneous flows. Bound Layer Meteorol. 2007;123(2):263–7.

Barbato G, Barini E, Genta G, Levi R. Features and performance of some outlier detection methods. J Appl Sta. 2011;38(10):2133–49.

The data set of Normalized Difference Vegetation Index; National Aeronautics and Space Administration. https://earthdata.nasa.gov/. Accessed 31 Ma 2021.

The report of greenhouse gas inventory of Seoul; Seoul Metropolitan Government. https://opengov.seoul.go.kr/sanction/view/?nid=21785389. Accessed 09 Dec 2021.

The data set. of building energy usage; Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport. https://open.eais.go.kr/. Accessed 31 Mar 2021.

The data set of floating population; Seoul Metropolitan Government. https://data.seoul.go.kr/. Accessed 31 Mar 2021.

The data set of traffic volume; Seoul Metropolitan Government. http://topis.seoul.go.kr/. Accessed 31 Mar 2021.

Jeong Y, Moon T. Analysis of Seoul urban spatial structure using pedestrian flow data–comparative study with ‘2030 Seoul Plan.’ J Korean Reg Dev Assoc. 2014;26(3):139–58.

Oda T, Maksyutov S. A very high-resolution (1 km × 1 km) global fossil fuel CO2 emission inventory derived using a point source database and satellite observations of nighttime lights. Atmos Chem Phys. 2011;11(2):543–56.

Tomohiro Oda S, Maksyutov. ODIAC Fossil Fuel CO2 Emissions Dataset (Version name: ODIAC2020b ODIACYYYY or ODIACYYYYa), Center for Global Environmental Research, National Institute for Environmental Studies. 2015. Doi: https://doi.org/10.17595/20170411.001. (Reference date*2: 2022/02/22).

Benedetti R, Rossini P. On the use of NDVI profiles as a tool for agricultural statistics: the case study of wheat yield estimate and forecast in Emilia Romagna. Remote Sens Environ. 1993;45(3):311–26.

Lin Y-S, Medlyn BE, Ellsworth DS. Temperature responses of leaf net photosynthesis: the role of component processes. Tree Physiol. 2012;32(2):219–31.

Crawford B, Grimmond C, Christen A. Five years of carbon dioxide fluxes measurements in a highly vegetated suburban area. Atmos Environ. 2011;45(4):896–905.

Hekkenberg M, Moll H, Uiterkamp AS. Dynamic temperature dependence patterns in future energy demand models in the context of climate change. Energy. 2009;34(11):1797–806.

Jalili A, Jamzad Z, Thompson K, Araghi M, Ashrafi S, Hasaninejad M, et al. Climate change, unpredictable cold waves and possible brakes on plant migration. Glob Ecol Biogeogr. 2010;19(5):642–8.

Diffenbaugh NS, Singh D, Mankin JS, Horton DE, Swain DL, Touma D, et al. Quantifying the influence of global warming on unprecedented extreme climate events. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2017;114(19):4881–6.

Acknowledgements

Chaerin Park is grateful for financial support from Hyundai Motor Chung Mong-Koo Foundation.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (NRF-2019R1A2C3002868).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CP and SJ created and designed the research. CP analyzed the data and was the primary author. HP and JY contributed to the design of this research. MSP, SSL, and SHP managed the eddy covariance observation system and compiled the data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Park, C., Jeong, S., Park, MS. et al. Spatiotemporal variations in urban CO2 flux with land-use types in Seoul. Carbon Balance Manage 17, 3 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13021-022-00206-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13021-022-00206-w