Abstract

Background

There is limited information on the longer-term outcome after transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) with new-generation prostheses compared to surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR). The aim of this study was to compare the mid-term outcomes after TAVR with Sapien 3 and SAVR with Perimount Magna Ease bioprostheses for severe aortic stenosis.

Methods

In a retrospective study, we included patients who underwent transfemoral TAVR with Sapien 3 or SAVR with Perimount Magna Ease bioprosthesis between January 2008 and October 2017 from the nationwide FinnValve registry. Propensity score matching was performed to adjust for differences in the baseline characteristics. The Kaplan-Meir method was used to estimate late mortality.

Results

A total of 2000 patients were included (689 in the TAVR cohort and 1311 in the SAVR cohort). Propensity score matching resulted in 308 pairs (STS score, TAVR 3.5 ± 2.2% vs. SAVR 3.5 ± 2.8%, p = 0.918). In-hospital mortality was 3.6% after SAVR and 1.3% after TAVR (p = 0.092). Stroke, acute kidney injury, bleeding and atrial fibrillation were significantly more frequent after SAVR, but higher rate of vascular complications was observed after TAVR. The cumulative incidence of permanent pacemaker implantation at 4 years was 13.9% in the TAVR group and 6.9% in the SAVR group (p = 0.0004). At 4-years, all-cause mortality was 20.6% for SAVR and 25.9% for TAVR (p = 0.910). Four-year rates of coronary revascularization, prosthetic valve endocarditis and repeat aortic valve intervention were similar between matched cohorts.

Conclusions

The Sapien 3 bioprosthesis achieves comparable midterm outcomes to a surgical bioprosthesis with proven durability such as the Perimount Magna Ease. However, the Sapien 3 bioprosthesis was associated with better early outcome.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03385915.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) with balloon-expandable [1,2,3] and self-expanding [4,5,6,7] bioprosthesis has proven its efficacy and safety compared to surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) in the treatment of aortic stenosis (AS) regardless of the operative risk. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials recently showed that TAVR is associated with significant reduction of all-cause mortality, a lower risk for stroke, atrial fibrillation and bleeding, but a higher risk for permanent pacemaker implantation and major vascular complications at 2 years compared to SAVR [8]. The indications for TAVR are expanding, but it is controversial whether TAVR should be performed on a larger scale because of limited data on the long-term outcome and valve durability of TAVR prostheses compared to SAVR prostheses. Similar longer-term survival after TAVR and SAVR is observed in randomized controlled trials [1, 6, 7], but studies reporting outcomes in the real-world populations have discordant findings [9,10,11,12]. Sustained valve hemodynamics and low reintervention rate is associated with the use of first-generation balloon-expandable Sapien bioprosthesis [1, 13]. However, a higher rate of structural valve deterioration leading to hemodynamic compromise was observed with the second-generation Sapien XT valve compared to the third-generation Sapien 3 valve prosthesis and the surgical valves in the PARTNER 2 trial [14]. Importantly, TAVR with different valve types and their iterations may result in discrepant outcomes and valve performance [14,15,16]. Therefore it is important to compare the outcomes of each TAVR prosthesis separately against SAVR prostheses with proven long-term durability [17, 18].

The third-generation balloon-expandable Sapien 3 (Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine, CA, USA) prosthesis has bovine pericardial leaflets that are attached inside a cobalt-chromium alloy frame, and unlike its predecessors (Sapien, Sapien XT, Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine, CA, USA) has an improved external layer of polyethylene terephthalate fabric seal to minimize the risk of paravalvular regurgitation along with a redesigned frame. During manufacturing, bovine pericardial leaflets undergo the same tissue processing (ThermaFix) intended to reduce the risk of leaflet calcification as in the latest generation surgical Perimount Magna Ease (Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine, CA, USA), which is regarded as the most durable surgical bioprosthesis [17].

The aim of this study was to compare the outcome after TAVR with the Sapien 3 and SAVR with the Perimount Magna Ease bovine pericardial prostheses. To our knowledge, this is the first direct comparison of these TAVR and SAVR bioprostheses.

Methods

Registry design

The FinnValve registry collected data on consecutive patients who underwent TAVR or SAVR with a bioprosthesis for AS at all Finnish university hospitals (Helsinki, Kuopio, Oulu, Tampere, Turku) between January 2008 and October 2017. Inclusion criteria were age > 18 years, primary aortic valve procedure with a bioprosthesis (TAVR or SAVR) for AS with or without associated coronary revascularization. The exclusion criteria were any prior aortic valve procedure, concomitant intervention for other valve or ascending aorta, active endocarditis and a procedure for aortic valve regurgitation. The study protocol was approved by the local Institutional Review Boards in all participating centres. Data was retrospectively collected in a dedicated electronic case report system by physicians and trained research nurses. Data on mortality was obtained from the Finnish Population Register Centre and data on cardiovascular interventions was retrieved from the registry of the Finnish National Institute for Health and Welfare. The follow-up was complete, except for those few patients not residing in Finland follow-up was truncated at hospital discharge. The study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines [19].

Patients and outcomes

Only patients who underwent transfemoral TAVR with Sapien 3 or SAVR with Perimount Magna Ease were included in this analysis. The choice between TAVR and SAVR was based on individual assessment by the local Heart Team. Patients in the TAVR group and concomitant coronary artery disease (CAD) underwent revascularization based on the discretion of the treating physician. Patients who underwent an emergency procedure or with associated severe clinical conditions were excluded (Fig. 1). The primary outcomes were in-hospital and 4-year all-cause mortality. The secondary outcomes were stroke, atrial fibrillation, permanent pacemaker implantation, major vascular complications, acute kidney injury, dialysis, moderate or severe paravalvular regurgitation, severe bleeding, reoperation for bleeding, red blood cell transfusion, annular or aortic rupture/dissection, conversion to cardiac surgery, coronary artery occlusion, deep sternal wound infection, postoperative intra-aortic balloon pump or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, ventricular wall injury and length of index hospitalization. Late secondary outcomes were permanent pacemaker implantation, coronary revascularization, prosthetic valve endocarditis and reoperation on the implanted aortic bioprosthesis.

The European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation (EuroSCORE) II criteria were applied for the definition of baseline variables and for surgical risk stratification [20]. Surgical risk was estimated also according to the Society of Thoracic Surgeons Predicted Risk of Mortality (STS-PROM) score. Coronary artery disease was defined as a ≥ 50% stenosis in a main coronary artery. Severe frailty was defined as Geriatric Status Scale 2–3 [21]. Stroke and major vascular complications were defined according to Valvular Academic Consortium 2 (VARC-2) [22] criteria and severe bleeding according to European Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting (E-CABG) bleeding scores 2–3 [23], i.e. transfusion of more than 4 units of red blood cells and/or reoperation for bleeding. Acute kidney injury was defined according to the KDIGO definition criteria [24].

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS v. 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) and SPSS v. 25.0 (IBM Corporation, New York, USA) statistical softwares. Data is presented as means ± standard deviation for continuous variables, and as counts and percentages for categorical variables. Mann-Whitney’s test was used to compare continuous variables, and the chi -square and Fisher’s exact tests were used to compare the categorical variables in the unmatched cohorts. A propensity score was calculated with a non-parsimonious logistic regression model including the following variables: age, gender, body mass index, diabetes, atrial fibrillation, extracardiac arteriopathy, chronic lung disease, hemoglobin, estimated glomerular filtration rate, stroke, pre-existing pacemaker, previous cardiac surgery, previous percutaneous coronary intervention, coronary artery disease, number of diseased coronaries, recent myocardial infarction, New York Heart Association class IV symptoms, acute heart failure or critical preoperative state, urgent procedure, left ventricular ejection fraction, systolic pulmonary pressure, mitral valve regurgitation, frailty and inactive malignancy. One-to-one propensity score matching was performed using the nearest-neighbour method and a caliper width of 0.2 of the standard deviation of the logit of the propensity score. Baseline variables and in-hospital outcomes in the matched population were compared with paired t-test and the McNemar test. Kaplan-Meier method with Klein-Moeschberger log-rank test was used to estimate late mortality. The risk for late adverse events was calculated with competing risk analysis and comparisons were performed using the Gray’s k-sample test for equality of cumulative incidence functions. Hazard ratios were calculated with their 95% confidence intervals (CI). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Study population

A total of 6463 patients were included in the FinnValve registry, and after exclusion of 4463 patients (Fig. 1), 2000 patients were subjects for the present analysis. Among them, 689 underwent TAVR with Sapien 3 bioprosthesis and 1311 patients underwent SAVR with Perimount Magna Ease prosthesis. The mean follow-up of the overall series and of the TAVR and SAVR cohorts was 3.6 ± 2.1, 2.4 ± 1.0 and 4.2 ± 2.1 years, respectively. The patients in the TAVR cohort were older (81.3 ± 6.4 vs. 74.0 ± 6.9 years), had more often co-morbidities and higher surgical risk based on the EuroSCORE II and STS-PROM scores (Table 1). After propensity score matching, 308 pairs with balanced baseline variables were identified (Table 1). The standardized difference after matching was < 0.1 for all baseline and operative covariates except for concomitant coronary revascularization, which was more common in SAVR (27.3% vs. 4.5%) despite a similar prevalence of coronary artery disease in the cohorts. The mean STS-PROM score was 3.5 ± 2.2% in the TAVR and 3.5 ± 2.8 in the SAVR cohort (p = 0.918) (Table 1). The sizes of implanted prostheses are summarized in Table 2.

Early outcomes

The early outcomes of the unmatched TAVR and SAVR cohorts are summarized in Table 3.

In the propensity matched cohorts, TAVR had a numerically lower in-hospital mortality (1.2% vs. 3.6%, p = 0.092) compared to SAVR (Table 3). Moreover, postoperative stroke was significantly less frequent after TAVR (0.3% vs. 3.6%, p = 0.006). A trend towards a higher need of permanent pacemaker implantation early after the procedure was observed in the Sapien 3 group. The incidence of moderate or severe paravalvular regurgitation was similar in both cohorts. TAVR was associated with lower rates of postoperative atrial fibrillation, acute kidney injury and severe bleeding compared to SAVR (Table 3). Major vascular complications were significantly more frequent in the TAVR cohort. Annular rupture occurred in one patient after Sapien 3 implantation (Table 3).

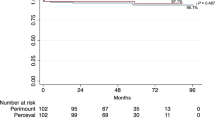

Mid-term outcomes after procedures

In the matched cohorts, Kaplan-Meier estimate of all-cause mortality was 7.5 and 6.5% at 1-year, 11.3 and 11.7% at 2-years, 12.9 and 14.7% at 3-years, 20.6 and 25.9% at 4-years in the SAVR and TAVR cohorts, respectively (HR 0.96; 95% CI 0.63–1.46; p = 0.910) (Fig. 2). At 4-years, the cumulative incidence of permanent pacemaker implantation was higher after TAVR (13.9% vs. 6.9%; HR 2.16; 95% CI 1.27–3.68). TAVR was associated with similar rates of late coronary revascularization (1.5% vs. 1.4%; HR 0.76; 95% CI 0.17–3.43), prosthetic valve endocarditis (0.6% vs. 0.5%; HR 1.02; 95% CI 0.06–16.10) and repeat aortic valve intervention (0.4% vs. 0.4%; HR 1.02; 95% CI 0.06–16.14) compared to SAVR.

In the matched groups, one patient in the TAVR group underwent aortic valve reintervention for structural valve deterioration and one patient in the SAVR group for paravalvular regurgitation. Additionally, the indications for reoperation in the unmatched cohorts were structural valve deterioration (1 patient with Sapien 3, 1 patient with Perimount), paravalvular regurgitation (5 patients with Perimount), and endocarditis (1 patient with Perimount).

Discussion

The main findings of our study are the following: 1) patients treated for severe AS with the transfemoral TAVR with the Sapien 3 bioprosthesis had similar mid-term mortality compared to patients who underwent SAVR with the Perimount Magna Ease bioprosthesis; 2) the risk for coronary revascularization, repeat aortic valve intervention and prosthetic valve endocarditis at 4 years was low and similar with both bioprostheses; 3) the Sapien 3 was associated with a higher cumulative rate of permanent pacemaker implantation than the Perimount Magna Ease bioprosthesis; 4) procedural safety in terms of stroke, atrial fibrillation, kidney injury and bleeding favoured TAVR, whilst lower rate of major vascular complications was observed with SAVR.

We hypothesised that unbiased evaluation on the outcomes after TAVR and SAVR could be feasible by including only the Sapien 3 and the Perimount Magna Ease bioprostheses, because the bioprostheses share some technological features such as bovine pericardial leaflets utilizing similar anti-calcification processes during manufacturing. Furthermore, the Perimount Magna Ease demonstrated an excellent durability among current surgical bioprostheses [17].

Our study showed that TAVR with the Sapien 3 prosthesis resulted in similar survival compared to SAVR with the Perimount Magna Ease at 4-years. Comparable mid-term outcomes between TAVR and SAVR were achieved in randomized controlled trials [1, 6, 7], but strict selection of the patients does not allow generalization of the results into real-life AS patients undergoing invasive treatment. Indeed, several observational studies have shown inferior mid-term outcomes after TAVR compared to SAVR. The findings from the OBSERVANT registry of 1300 matched patients undergoing TAVR with first/second generation prostheses and SAVR showed that TAVR was associated with higher all-cause mortality (44.5% vs. 35.8%) at 5-years. Mortality rate in the OBSERVANT registry exceeded our 4-year mortality already after 2.5 years [11]. Markedly inferior 5-year survival after TAVR was observed also in the analysis from the French Medical Information System database, with all-cause death of 52% after TAVR and 37% after SAVR in the matched patient populations [9]. There are few possible explanations for such different mid-term outcomes between the studies. Firstly, the Sapien 3 bioprosthesis carried a decreased risk of structural valve deterioration compared to its predecessor the Sapien XT valve, and performed similarly as the surgical valves in the PARTNER 2 study [14]. In addition, a propensity score matched study combining data from the SOURCE XT and the SOURCE 3 registries showed improved survival with Sapien 3 compared to Sapien XT valves [15]. A low incidence (1.9%) of moderate paravalvular regurgitation with Sapien 3 in our study was in concordance with other studies, and potentially impacted the outcomes [25]. Secondly, including different generations of balloon-expandable and self-expanding TAVR prostheses in previous observational studies may have introduced a significant bias [16].

The question of valve durability is becoming more relevant as TAVR is adopted for lower- risk patients. Several studies showed reasonable durability of surgical bioprosthesis up to 15–20 years after SAVR [17], but variable definitions used for structural valve deterioration in surgical prostheses makes benchmarking for transcatheter valves difficult [26]. The incidence of structural valve deterioration cannot be estimated in our study since a comprehensive echocardiographic follow-up data was not available and solely reintervention rate inevitably leads to a major underestimation of its true incidence. This clearly limits the interpretation of our results regarding the durability of the Sapien 3 prosthesis. However, the need for reintervention for aortic valve complications was very low in both cohorts.

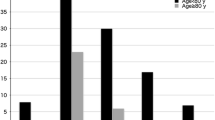

The cumulative incidence of permanent pacemaker implantation in the Perimount group remained low and stable, while in the Sapien 3 group permanent pacemaker implantation was increasingly needed along the study period. Since pacing after TAVR may have long-term consequences for the patient [27], we should aim to reduce the risk for permanent pacemaker implantation by adopting higher implantation technique and avoiding excess oversizing with the Sapien 3 prosthesis [28, 29].

The prevalence of coronary artery disease was similar in the matched cohorts, but concomitant coronary revascularization was performed only in 14% of the patients with coronary artery disease in the TAVR group compared to 87% revascularization rate in patients with coronary artery disease in the SAVR group. Complete revascularization during SAVR is recommended to avoid postoperative left ventricular systolic dysfunction and excess mortality after surgery [30], but the best revascularization strategy during TAVR is not established yet, which most likely explains the lower revascularization rate in the TAVR group. Interestingly, such a low rate of coronary revascularization at the time of procedure did not expose patients undergoing TAVR to an increased need of revascularization at 4-years with similar mortality rate compared to SAVR. However, we have to interpret this finding with caution because the increased risk related to coronary artery disease in the TAVR patients is driven by its severity [31], and our definition criteria did not capture patients only with the most severe coronary artery disease.

Procedural safety is one of the major concerns in the decision-making process. The present findings indicate that TAVR with balloon-expandable Sapien 3 is safe with very low rates of annular rupture and coronary obstruction. Furthermore, TAVR was associated with lower incidence of stroke, acute kidney injury, atrial fibrillation and bleeding compared to SAVR. However, the rate of major vascular complications was still higher in TAVR compared to SAVR. This favourable safety profile of TAVR over SAVR is in alignment with current knowledge [8].

Limitations

The retrospective nature is the major limitation of this study. Secondly, the mean follow-up in the TAVR cohort was shorter than in the SAVR cohort. Third, comparative analysis of the TAVR and SAVR cohorts was based on propensity score matching and unrecognized confounders might have had an impact on the results. Finally, the lack of complete echocardiographic follow-up prevented an analysis of structural valve deterioration which might have occurred in these cohorts.

Conclusions

In this nationwide study, transfemoral TAVR with Sapien 3 prosthesis achieved similar mid-term outcomes with better procedural safety compared to SAVR with Perimount Magna Ease bioprosthesis.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used during the current study are not available due to legal restrictions.

Abbreviations

- EuroSCORE:

-

European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation

- PARTNER:

-

Placement of Aortic Transcatheter Valves

- SAVR:

-

Surgical aortic valve replacement

- STS-PROM:

-

Society of Thoracic Surgeons Predicted Risk of Mortality

- TAVR:

-

Transcatheter aortic valve replacement

References

Mack MJ, Leon MB, Smith CR, Miller DC, Moses JW, Tuzcu EM, et al. 5-year outcomes of transcatheter aortic valve replacement or surgical aortic valve replacement for high surgical risk patients with aortic stenosis (PARTNER 1): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;385:2477–84.

Leon MB, Smith CR, Mack MJ, Makkar RR, Svensson LG, Kodali SK, et al. Transcatheter or surgical aortic-valve replacement in intermediate-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1609–20.

Mack MJ, Leon MB, Thourani VH, Makkar R, Kodali SK, Russo M, et al. Transcatheter aortic-valve replacement with a balloon-expandable valve in low-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:1695–705.

Reardon MJ, Van Mieghem NM, Popma JJ, Kleiman NS, Søndergaard L, Mumtaz M, et al. Surgical or Transcatheter aortic-valve replacement in intermediate-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1321–31.

Popma JJ, Deeb GM, Yakubov SJ, Mumtaz M, Gada H, O’Hair D, et al. Transcatheter aortic-valve replacement with a self-expanding valve in low-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:1706–15.

Gleason TG, Reardon MJ, Popma JJ, Deeb GM, Yakubov SJ, Lee JS, et al. 5-year outcomes of self-expanding Transcatheter versus surgical aortic valve replacement in high-risk patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:2687–96.

Søndergaard L, Ihlemann N, Capodanno D, Jørgensen TH, Nissen H, Kjeldsen BJ, et al. Durability of Transcatheter and surgical bioprosthetic aortic valves in patients at lower surgical risk. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:546–53.

Siontis GCM, Overtchouk P, Cahill TJ, Modine T, Prendergast B, Praz F, et al. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation vs. surgical aortic valve replacement for treatment of symptomatic severe aortic stenosis: an updated meta-analysis. Eur Heart J. 2019;40:3143–53.

Armoiry X, Obadia JF, Pascal L, Polazzi S, Duclos A. Comparison of transcatheter versus surgical aortic valve implantation in high-risk patients: A nationwide study in France. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2018;156:1017–1025.e4.

Schaefer A, Schofer N, Goßling A, Seiffert M, Schirmer J, Deuschl F, et al. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation versus surgical aortic valve replacement in low-risk patients: a propensity score-matched analysis. Eur J Cardio-Thoracic Surg. 2019;56:1131–9.

Barbanti M, Tamburino C, D’Errigo P, Biancari F, Ranucci M, Rosato S, et al. Five-year outcomes of Transfemoral Transcatheter aortic valve replacement or surgical aortic valve replacement in a real world population. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;12:e007825.

Virtanen MPO, Eskola M, Jalava MP, Husso A, Laakso T, Niemelä M, et al. Comparison of outcomes after Transcatheter aortic valve replacement vs surgical aortic valve replacement among patients with aortic stenosis at low operative risk. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:e195742.

Douglas PS, Leon MB, Mack MJ, Svensson LG, Webb JG, Hahn RT, et al. Longitudinal hemodynamics of transcatheter and surgical aortic valves in the PARTNER trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2017;2:1197–206.

Pibarot P, Hahn R. Incidence, predictors and outcome of structural valve deterioration in transcatheter vs. SAVR: five year follow-up from the PARTNER II trials in intermediate-risk patients. Data presented in PCR London Valves 18th November ; London; United Kingdom. https://www.pcronline.com/Cases-resources-images/Resources/Course-videos-slides/2019/Late-Breaking-Trials-at-PCR-London-Valves-2019-Session-2?auth=true. Accessed 17 Mar 2020.

Schymik G, Wendler O, Hengstenberg C, et al. Outcomes of transfemoral balloon expandable transcatheter aortic valve implantation: Comparison of two subsequent valve generations. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2019:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1002/ccd.28621.

Van Belle E, Vincent F, Labreuche J, Auffret V, Debry N, Lefèvre T, et al. Balloon-expandable versus self-expanding Transcatheter aortic valve replacement. Circulation. 2020;141:243–59.

Forcillo J, Pellerin M, Perrault LP, Cartier R, Bouchard D, Demers P, et al. Carpentier-Edwards pericardial valve in the aortic position: 25-years experience. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;96:486–93.

Nielsen PH, Hjortdal V, Modrau IS, Jensen H, Kimose H-H, Terp K, et al. Durability after aortic valve replacement with the Mitroflow versus the Perimount pericardial bioprosthesis: a single-Centre experience in 2393 patients. Eur J Cardio-Thoracic Surg. 2016;49:1705–10.

von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e296.

Nashef SAM, Roques F, Sharples LD, Nilsson J, Smith C, Goldstone AR, et al. EuroSCORE II. Eur J Cardio-Thoracic Surg. 2012;41:734–45.

Rockwood K, Stadnyk K, MacKnight C, McDowell I, Hebert R, Hogan DB. A brief clinical instrument to classify frailty in elderly people. Lancet. 1999;353:205–6.

Kappetein AP, Head SJ, Généreux P, Piazza N, van Mieghem NM, Blackstone EH, et al. Updated standardized endpoint definitions for transcatheter aortic valve implantation: the valve academic research Consortium-2 consensus document†. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:2403–18.

Biancari F, Ruggieri VG, Perrotti A, Svenarud P, Dalén M, Onorati F, et al. European multicenter study on coronary artery bypass grafting (E-CABG registry): study protocol for a prospective clinical registry and proposal of classification of postoperative complications. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2015;10:90.

Acute Kidney Injury Work Group. Section 2: AKI definition. Kidney Int Suppl. 2012;2:19–36.

Pibarot P, Hahn RT, Weissman NJ, Arsenault M, Beaudoin J, Bernier M, et al. Association of paravalvular regurgitation with 1-year outcomes after transcatheter aortic valve replacement with the SAPIEN 3 valve. JAMA Cardiol. 2017;2:1208–16.

Fatima B, Mohananey D, Khan FW, Jobanputra Y, Tummala R, Banerjee K, et al. Durability data for bioprosthetic surgical aortic valve. JAMA Cardiol. 2019;4:71–80.

Costa G, Zappulla P, Barbanti M, Cirasa A, Todaro D, Rapisarda G, et al. Pacemaker dependency after transcatheter aortic valve implantation: incidence, predictors and long-term outcomes. EuroIntervention. 2019;15:875–83.

Husser O, Pellegrini C, Kessler T, Burgdorf C, Thaller H, Mayr NP, et al. Predictors of permanent pacemaker implantations and new-onset conduction abnormalities with the SAPIEN 3 balloon-expandable Transcatheter heart valve. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;9:244–54.

Mauri V, Reimann A, Stern D, Scherner M, Kuhn E, Rudolph V, et al. Predictors of permanent pacemaker implantation after Transcatheter aortic valve replacement with the SAPIEN 3. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;9:2200–9.

Nishimura RA, Otto CM, Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Erwin JP, Guyton RA, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the Management of Patients with Valvular Heart Disease. Circulation. 2014;129:e521–643.

D’Ascenzo F, Verardi R, Visconti M, Conrotto F, Scacciatella P, Dziewierz A, et al. Independent impact of extent of coronary artery disease and percutaneous revascularisation on 30-day and one-year mortality after TAVI: a meta-analysis of adjusted observational results. EuroIntervention. 2018;14:e1169–77.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was financially partly supported by the Competitive State Research Financing of the Expert Responsibility area of Tampere University Hospital. MPOV received personal research grants from Aarne Koskelo Foundation and from Paavo Ilmari Ahvenainen Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MPOV, ME and FB designed the study, collected and analysed data and drafted the manuscript. MN, AVa, PR, JA: designed the study, interpreted data and revised the manuscript; MS, TJ, TL, AH, MPJ, TT, TA, PM, E-MK, SD, ML, TM, AVe collected and interpreted data, and revised the manuscript; SR, PD’E performed the statistical analyses. All authors read and accepted the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the local Institutional Review Boards in each participating centre.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

MS is a proctor for Medtronic; ML is a proctor for Boston Scientific All the other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Virtanen, M.P.O., Eskola, M., Savontaus, M. et al. Mid-term outcomes of Sapien 3 versus Perimount Magna Ease for treatment of severe aortic stenosis. J Cardiothorac Surg 15, 157 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13019-020-01203-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13019-020-01203-1